Mark W. Tiedemann's Blog, page 89

January 14, 2011

Other Buzzzzzzzz

I am not going to go see the new Green Hornet movie. I knew that long before its release, when I heard Seth Rogen had been cast as the Hornet. I just knew it would be a waste of everyone's time, money, and sentiment.

I'm sorry. Hollywood has been doing superhero movies now for decades and they've gotten a few of them pretty right. Except for a ridiculous semi-musical romantic interlude, the first Superman movie with Christopher Reeve was fine. Mostly this was due to Reeve and co-star Gene Hackman (who can save just about any movie), but they treated the material lovingly the whole way. Subsequent versions, not so much. In fact, by the fourth outing as Superman, Reeve must have been a bit embarrassed. Clearly, the problem with sequels is that we're dealing with material that was born to be a serial, and the best medium for that is television, not big budget cinema. That said, a few of these aren't so bad. It helps not being immersed in the comic books to begin with (for instance, I was able to enjoy all three of the primary X-Men films without getting all worked up over the liberties taken by the studio that incensed many dedicated fans—except for a Baker's Dozen back when I was 13 or 14, I did not follow the comics), but I can more or less enjoy many of these outings. Have to admit, though, to date the Marvel franchise has fared much better.

But the Green Hornet is another matter and one of the things that Hollywood so often forgets is that the material must be taken seriously!

These were the guys I grew up with. Brit Reid and Kato as played by Van Williams and Bruce Lee, 1966 to 67. The car especially, Black Beauty, really rocked. Now, I saw these in first-run and haven't seen them since, so doubtless they have dated and dated badly. But my imagination took the original viewing and went amazing places with it, and that is the problem with a lot of these films.

No doubt the film-makers took a cue from the Iron Man movies. There is a lot of humor in those films, but—the films are not humorous. Tony Stark is funny, but funny within context—and with a lot of credit going to Robert Downey Jr. for just doing a tremendous job in the role—and that's something film makers fail to grasp time and again.

For instance, the best Three Musketeer films ever made were the Salkind productions in the 70s with Michael York and Oliver Reed. Great films. And funny! But funny as a consequence of the action within context—the characters themselves were not jokes, they were serious. Much later, a third film was made, Return of the Three Musketeers, with the same cast, but something had been lost—they were turned into buffoons in order to artificially inject humor rather than letting it arise from the context, and it is painful to watch.

Long ago now Tim Burton made a Batman movie and cast a comic actor, Michael Keeton. A lot of people probably moaned, fearing the worst. But Burton treated the material seriously and Keeton played it straight. Likewise in the sequel, but when Burton lost control Keeton bailed, and good for him, because the studio starting injecting jokes, much as had been done with the James Bond films, and taking the premise much less seriously, until they produced a truly foul film (one of the few I have been utterly unable to watch more than 15 minutes of).

Keeton, however, had done serious films before. He had a reputation as a comic actor, but more in the line of Jack Lemmon than Seth Rogen, who has gone from one slapstick dumbshit vehicle to another, and apparently the studio opted to play to his strengths in that regard here.

I don't like movies or television that rely on stupidity to carry the story. That's why I no longer watch most sitcoms. Stupid is not funny to me. The great comics knew that good comedy was not to make fun of people's stupidity but to derive the humor from stupid situations. Charlie Chaplin's Little Tramp was not stupid. Lucille Ball's character was not stupid, either, she simply never knew enough to follow through effectively on her schemes, and the situation tripped her up.

That said, superhero stories walk a fine line between significance and the absurd. I mean, really, these people are improbable at best. It is all too easy to paint them as ridiculous or such utter fantasies that no real drama could result from their stories. It's difficult to write sympathetically, not to say powerfully, about people who are so much more than average. And the scenarios!

But that's what makes them iconic, because they achieved that balance and then some. So you have to be careful when translating them from one medium to another. In this instance, they clearly didn't get it.

Now back to our regularly scheduled day.

January 13, 2011

Challenge the B.S.

Let's be clear: no one should advocate censorship.

That said, we need to understand the power of language. Images matter, words matter, what you say has an effect. Every propagandist in history has grasped this essential truth. Without oratory, Hitler and Goebbels would never have turned Germany into a killing machine.

The only antidote, however, is not less but more. Not more propaganda, just more words, more images, more information. More truth.

Ah, but, as the man said, What is truth?

Sarah Palin, or her speech writers, has decided to play with that a bit and compare the criticism against her rather fevered rhetoric to the Blood Libel. Now, she has a perfect right to do this. Metaphor, simile, hyperbole—these are all perfectly acceptable, even respectable, tools of communication. No one—NO ONE—should suggest she has no right to state her case in any manner she chooses.

What is lacking, however, is perspective and a grasp of the truth. Not fact. But truth. Is there any truth in her assertion that the backlash against what is perceived to be an inappropriate degree of aggressive even violent imagery is the equivalent of two millennia of persecution resulting in the near-extinction of an entire human community? Absolutely none. In fact, what she has done is add substance to the perception that she is a callous, insensitive, and rather inept manipulator of public opinion. In other words, a propagandist.

What should follow now is a discourse on the actual Blood Libel and debate on the public airwaves over whether or not this is a valid comparison. Then there should be a review of the statistical links between violent political rhetoric and actual violence. We should have a discussion—not a condemnation, but a discussion, bringing into the conversation more information, more fact, and more than a little truth.

Do I think Sarah Palin is responsible for Loughner's actions in Tuscon? No. Loughner is, in my opinion, a seriously disturbed young man and would likely have gone off on anyone at any time. However, he chose as his target a politician, one who had been singled out by the party machinery of the Right as a target. I believe Palin when she says her intent was to eliminate Gifford by popular vote. I do. I don't accept as credible the idea that she would have sanctioned assassination on anyone. She wants to play a part in national politics, she wants to win, and insofar as it may be understood, I think she wants to win within the system. Do I also believe she thinks some of the rules of the system are bad and that she is willing to color outside the lines? Certainly. But that's not a singular criticism, either.

Do I, however, believe that we have a toxic atmosphere of political discourse which a certain segment of the population may be incapable of parsing as metaphor? Absolutely.

Here's a smattering of samples from over the years from a variety of sources.

"I tell people don't kill all the liberals. Leave enough so we can have two on every campus—living fossils—so we will never forget what these people stood for."—Rush Limbaugh, Denver Post, 12-29-95

"Get rid of the guy. Impeach him, cen…sure him, assassinate him."—Rep. James Hansen (R-UT), talking about President Clinton

"We're going to keep building the party until we're hunting Democrats with dogs."—Senator Phil Gramm (R-TX), Mother Jones, 08-95

"My only regret with Timothy McVeigh is he did not go to the New York Times building."—Ann Coulter, New York Observer, 08-26-02

"We need to execute people like John Walker in order to physically intimidate liberals, by making them realize that they can be killed, too. Otherwise, they will turn out to be outright traitors."—Ann Coulter, at the Conservative Political Action Conference, 02-26-02

"Chelsea is a Clinton. She bears the taint; and though not prosecutable in law, in custom and nature the taint cannot be ignored. All the great despotisms of the past—I'm not arguing for despotism as a principle, but they sure knew how to deal with potential trouble—recognized that the families of objectionable citizens were a continuing threat. In Stalin's penal code it was a crime to be the wife or child of an 'enemy of the people.' The Nazis used the same principle, which they called Sippenhaft, 'clan liability.' In Imperial China, enemies of the state were punished 'to the ninth degree': that is, everyone in the offender's own generation would be killed and everyone related via four generations up, to the great-great-grandparents, and four generations down, to the great-great-grandchildren, would also be killed."—John Derbyshire, National Review, 02-15-01

"Two things made this country great: White men & Christianity. The degree these two have diminished is in direct proportion to the corruption and fall of the nation. Every problem that has arisen (sic) can be directly traced back to our departure from God's Law and the disenfranchisement of White men."—State Rep. Don Davis (R-NC), emailed to every member of the North Carolina House and Senate, reported by the Fayetteville Observer, 08-22-01

"I'm thinking about killing Michael Moore, and I'm wondering if I could kill him myself, or if I would need to hire somebody to do it. No, I think I could. I think he could be looking me in the eye, you know, and I could just be choking the life out." —Glenn Beck (on air), May 17, 2005

Do I think Sarah Palin has contributed to that? Yes. Ever since her appearance on the national stage and her absurd squib about pit bulls and hockey moms. A great many people reacted positively to that, but I think a great many more, even if they were inclined to support her, scratched their heads at that and went "Huh?"

Why a pit bull? Why hockey? Pit bulls, of course, are perceived as dangerous animals. And hockey is perceived as a violent sport. (In a completely unscientific and wholly personal anecdotal sample, I have attended two hockey games in my life. One a professional game, the other at a community rink through the Y. Fist fights were a feature of both and at the pro game it was the fist fight that seemed to get the most audience applause. At the Y game, it was between 10 to 12 year olds, who did not fight, but the adults at one point, in a heated exchange over a perceived infraction, did get into an altercation.) Traditionally, it would be soccer moms. Why the substitution? Well, you could say that Alaska is simply not a big soccer state and hockey would be the sport of choice. On the other hand, she was addressing a national audience and her speech writers should have known that the more commonly understood expression would be soccer, so we have to assume it was a deliberate choice. And comparing mothers to a dangerous pet?

I could go on. The fact is, she was challenging her potential constituency to be tough, to be aggressive, to be willing to tear into the opposition, to support the brawl over the debate. It was a very clumsy way to do it, but the phrase has become part of America's lexicon of aphorisms, so it must have had some cachet with enough people to matter.

The people who were unaffected by this were those who simply had broader experience with hyperbole. If you wish to protect people from the negative influences of certain kinds of speech, you expose them to more and more diverse types of speech, not less. You do not censor. Rather, you widen their scope, show them alternatives, and give them more. The antidote to bad speech is not a ban, but to provide good speech, and allow people to become experienced in how to deal with it. The people who are often the most susceptible to deriving the wrong signals from speech are those who have the least experience with diverse speech.

So when someone decides to compare Obama to a Nazi, the solution is to rehearse what the Nazis were and point out how the comparison is ridiculous. If someone asserts how horrible liberalism has been for the country, the answer should be a catalogue of liberal successes that have now become part of what conservatives are defending. If someone suggests that our countries injuries are because we have extended civil rights to gays or banned prayer from public schools, ask how any of that played into Pearl Harbor, the Lusitania, the Maine, or the Civil War?

The answer to hatemongers is not to tighten controls on speech but to open the floodgates to fact and truth. You don't expunge what you find disagreeable, you displace it with something of value. Take their audience away.

If we wish to have reasonable discourse, then we must produce reasonable speech and put it out there, unapologetically, and in sufficient quantity that the propagandists lose credibility. We haven't been doing that. We've been, perhaps, assuming too much. We assume people are reasonable. People can be, but many have to be taught how, or at least shown the methods of communicating that reasonableness. We have assumed that the absurdisms of the pundits will fade simply because they are absurd, but maybe that assumption is in error. Confrontation is difficult and often disagreeable, but conceding to misrepresentations, half-truths, and distortions only makes us look stupid and weak and makes us all vulnerable.

So maybe we should opt not to lay blame. Maybe we should just do what we should have done all along—challenge the bullshit.

January 11, 2011

Taking Cues

I'd intended to give this a little more thought, but the events in Arizona have prompted a response now.

In the last post, I opined about the atmosphere in the country generated by overheated rhetoric and the irrationality that has resulted from seemingly intransigent positions. Some of the responses I received to that were of the "well, both sides do it" variety (which is true to an extent, but I think beside the point) and the "you can't legislate civility or impose censorship" stripe.

As it is developing, the young man who attempted to murder Representative Gifford—and succeeded in killing six others—appears to be not of sound mind. We're getting a picture of a loner who made no friends and indulged in a distorted worldview tending toward the paranoid. How much of his actions can be laid on politics and how much on his own obsessions is debatable. Many commentators very quickly tried to label him a right-winger, based largely on the political climate in Arizona and that he targeted a moderate, "blue dog" Democrat. This in the context of years of shrill right-wing political rhetoric that fully employs a take-no-prisoner ethic, including comments from some Tea Party candidates about so-called Second Amendment solutions. It's looking like trying to label this man's politics will be next to impossible and, as I say, if he is mentally unbalanced, what real difference does that make? (Although to see some people say "Look, he's a Lefty, one of his favorite books is Mein Kampf " is in itself bizarre—how does anyone figure Mein Kampf indicates leftist political leanings? Because the Nazis were "National Socialists"? Please.)

Whatever the determination of Mr. Loughner's motives may turn out to be, his actions have forced the topic of political stupidity and slipshod rhetoric to the forefront, at least until Gabrielle Gifford is out of danger of dying. Regardless of his influences, in this instance he has served as the trigger for a debate we have been needing to have for decades. This time, hopefully, it won't be shoved aside after a few well-meaning sound-bites from politicians wanting to appear sensitive and concerned, only to have everyone go right back to beating each other bloody with nouns and verbs.

But while it may be fair to say that Mr. Loughner is unbalanced and might have gone off and shot anyone, the fact is he shot a politician, one who had been targeted by the Right. Perhaps the heated rhetoric did not make Mr. Loughner prone to violence, but what about his choice of victims?

There is a dearth of plain speaking across the political spectrum. That is as far as I'm willing to concede the charge that "both sides" indulge the same rhetoric. They do not, at least not in the same degree, and this is one time when the Right has more to answer for than the Left. The rhetorical shortcomings of the Left are of a different kind, but nowhere near as divisive as what we've been hearing from the folks who bring us Fox News and the national pundit circus.

"Why don't we hear congressmen talking about banning Wicca in the military? Or banning the occult in America? This shooter was a stone-cold devil-worshiper! A left-wing pot-smoking lunatic!"—Michael Savage.

That's helpful. Now we've dragged the supernatural into it, something I don't believe anyone on the Left has done yet. Mr. Savage seems not to have understood the call for "toned-down rhetoric" for what it actually means, but somehow something to be responded to as if it were an attack on his freedom to make outrageous assertions.

The fact is, the majority—the vast majority—of assaults over politically sensitive issues in the past three decades have come from a perspective that can only be characterized as supportive of the Right. It may be that such issues attract the nutwings. It may be that more nutwings find themselves in sympathy with conservative issues. But it is more likely that the apocalyptic messaging coming from the Right has the correct tone and resonance to provide nutwings with proof that their personal paranoias are correct and they are justified in acting upon them.

In his excellent book, Talking Right, linguist Geoffrey Nunberg chronicles the shift in language in our public discourse and shows how the choices made by pundits, think tanks, speech writers, and politicians themselves have pushed the discourse further and further to the Right and making it a battle, for some a war, to stop Liberalism. Increasingly, right-wing rhetoric has adopted a "take no prisoners" intransigence. Even when cooperation occurs, when bipartisanship happens, and compromise is achieved, the Right makes it look like they won over the Left, to the point where the Left appears to be not only ineffectual but a burden, a drag on society, and in some instances a scourge to be expunged.

For the most part this has been carried out by the well-honed machine that is the right-wing media. Republican politicians don't have to say the truly objectionable things because there is a cadre of talking heads who will do it for them.

It is fair to say, however, fair to ask: why can't the Left do this?

In a fascinating passage in Nunberg's book he describes the problem:

"I happened on a striking demonstration of the right's linguistic consistency back in 1996, when I was playing around with one of those programs that produces an automatic summary of texts by analyzing their word frequency and recurrent syntactic patterns. out of curiosity, I ran it on a collection of all the speeches that had been given over the first two nights of the Republican National Convention in San Diego, and it promptly distilled them into five key sentences…but when I tried the same experiment a month later on the combined texts of the speeches from the first two nights of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the software returned pure word salad. Because Democrats are chronically incapable of staying on message, no single group of phrases rose to the statistical surface."

The five sentences? Here:

We are the Republican Party—a big, broad, diverse and inclusive party, with a commonsense agenda and a better man for a better America, [insert politician's name]. We need a leader we can trust. Thank you, ladies and gentlemen, for being part of this quest in working with us to restore the American dream. The commonsense Republican proposals are the first step in restoring the American dream because Republicans care about America. But there is no greater dream than the dreams parents have for their children to be happy and to share God's blessings.

(Lundberg traces the current demonization of Liberal to 1988, when in a speech Ronald Reagan—the Great Communicator—said "The masquerade is over. It's time to…say the dreaded L-word; to say the policies of our opposition are liberal, liberal, liberal." The Democratic candidate that year, Michael Dukakis, rather than counter the charge, ducked it, and the expression "the L-word" entered the lexicon of public discourse the same way as other unmentionable epithets have—the N-word, the F-word, etc. So Liberal was reduces to a slur, something not said in polite company. We have not recovered since.)

It's interesting to look at those five sentences and parse what they actually seem to suggest. The word "dream" is in there four times, the word "commonsense" twice, the word "America" three times. The question to ask is, what comprises the dream and what do they mean by commonsense? And do you have commonsense dreams? Dreams by definition are in some way outside the practical, and usually commonsense refers to some species of practical.

But for the moment, let's look at that American Dream so oft mentioned and so seldom examined.

James Truslow Adams, in his book Epic of America in 1931, first coined the phrase:

The American Dream is that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement. It is a difficult dream for the European upper classes to interpret adequately, also too many of us ourselves have grown weary and mistrustful of it. It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.

This more than a year and a half into the Great Depression demands context. The "dreams" of millions of Americans had been thoroughly dashed in the Crash of '29. People were out of work, losing their homes, with little or no possibility of relief. At that time there were no safety nets. No unemployment insurance, no welfare to speak of, nothing provided in the event that private enterprise failed to absorb the majority of available workers, who depended on wages to maintain themselves and their families.

President Hoover stood resolutely opposed to providing any kind of direct aid, fearing it would sap the will of workers to seek employment. He was, along with most "conservatives" of his time, willing to see millions destituted rather than risk undermining the vaunted "work ethic" that had fueled American industrial and economic ascendence to that point.

This was also the era in which unions were still struggling to make inroads in the struggle to achieve fair labor practices. Unions were opposed by the conservatives of the era because of fears that giving workers power to determine the conditions under which they labored would undermine the entrepreneurial spirit.

What is most striking, however, about Mr. Adams' words is his downplaying of the material in lieu of a kind of independent self value, a notion that people have a right to be treated equally as worthwhile, and to be free to pursue their own vision of improvement. This kind of appreciation for what might called a basic right of civilized life has been talked about and worked toward through most of Western history, no less elsewhere that here, but seldom more polarized and equivocated than America.

Consider:

Self rule via a popularly elected government subject to recall—liberal idea.

Recognition of individual value regardless of station—liberal idea.

Emancipation of bond slaves as a fundamental human right—liberal idea.

Electoral franchise available to all adults, regardless of race or gender—liberal idea.

Recognition that women are individuals unto themselves with all the rights and privileges pertaining to a fully enfranchised person—liberal idea.

Protection of children from exploitation through child labor laws—liberal idea.

Right of workers to be free from arbitrary dismissal without cause from jobs—liberal idea.

Limited work week—liberal idea.

Universal public education—liberal idea.

The list could go on. And by Liberal I mean the notion that progress to achieve social egalitarianism is a positive value.

It also means, implicitly, that people should not judge others according to myths, stereotypes, or prejudices. This is embodied in the old maxim that in this country "anybody can become the president." The truth of this maxim is debatable, but underlying it is Liberal concept of egalitarian value.

In each of the aforementioned instances, the conservatives of the time opposed—sometimes aggressively, even violently—the changes necessary to make these ideas a reality. And by conservative I mean a philosophy of stasis, the maintenance of status quo, or at the very least the preservation of privilege among the properties few.

Whether it is true or not in every instance, conservatism has been the ideological partner of the well off. It has stood generally in opposition to change, often for good cause (Speaker Reed of the House of Representatives during the McKinley administration stood in opposition to a change in policy that allowed for America to become an imperial nation by launching a war on Spain. He was a conservative by any definition and in this instance he saw the manipulation of rules of procedure by those eager to go to war as an unsupportable change), but also quite often simply to preserve the privileges of those viewed as successful.

So what is it Liberals have to be ashamed of?

It is this: for being unwilling or unable to define progress in such a way that the general public can support it and to stand up for their support of such progress. Liberals have often been unwilling to take stands. The Left does, but usually it is a Left that is even farther left than Liberal comfort allows. Radicals. Extremists. And by their efforts, everything on the Left has come to be vilified. Liberals ride the wave in to progress and after the achievement claim to support what has been accomplished. Liberals tend to be accommodationist to the point of letting conservatives—or the Right—define them, usually to their detriment.

What is fascinating is how after every period of explosive progressive change, the new order, sometimes quite rapidly, becomes the status quo and defended by conservatism, so that Liberalism almost always loses credit for what it has accomplished.

But that seems now to be just an appearance. The Right has been trying to roll back progress for some time now. Missouri is about to vote on a Right To Work bill—again—which sounds reasonable on its face, but is just one more attempt to break unions. Unions have lost ground since the Seventies and in many instances they have been their own worst enemies. Any long-established entrenched power system becomes corrupt and, yes, conservative, and can become unreasonable. But if anyone thinks getting rid of them will redound to workers' benefit, they are delusional. Right To Work has in those states where it has been in force for a long time, translated into lowered pay, lowered benefits, lowered standards, and higher abuses—many of which have been countered by Federal laws prohibiting certain practices.

By Mr. Lundberg's analysis, the Right has taken control of the language and ridden that control into power more often than not since Reagan. And those five key sentences of Republican solidarity seem to attract people, if not to join them outright, at least to demand some kind of compliance to them by their own ideological spokespersons. But just what is it that those five sentences promise?

Nothing. They are an acknowledgment of sentiment, not a program.

What the Right does speaks for itself. Lower taxes, gutting of education, reduction of resources to basic research, and, since 9/11, an increase in domestic paranoia that targets an enemy it cannot clearly define but has resulted in restrictions on all of us. A support of big business (and by that I mean corporations so large as to constitute de facto governements within themselves, many of them functionally stateless), and an opposition to secularism. A promotion of the idea of American Exceptionalism based less on actual achievement than on birth-right (hence the current discussions over revision of the 14th Amendment) at the expense of the very commonsense approach they tout.

Lay on top of all this the superheated rantings on the part of their mouthpieces, you have an atmosphere in which anything that equivocates, that seeks to reflect, that calls for honest debate, that might require rethinking of positions, any compromise is seen by the faithful as treason.

But against what?

I have some thoughts on that. Stay tuned.

January 10, 2011

If You Can't Play Nicely With Your Toys…

We finally have our Kennedy Moment in the current political climate.

Saturday, January 8th, 2011, is likely to go down as exactly that in the "Where were you when?" canon. On that day, Jared Lee Loughner, age 22, went on a shooting rampage at a supermarket parking lot in Tucson, Arizona, killing six people and wounding eighteen others before bystanders tackled him. (There may be a second man involved, police are searching for him.)

The rhetoric is already ramping up on both sides over this. Loughner is a young man with, apparently, a history of mental difficulties. What is interesting in all this is the suggestion that Sarah Palin is partly responsible. Note:

Sarah has made a great deal out of her image as a gun-toting Alaskan Libertarianesque "True Amuricin" and she liberally deploys the iconography of Second Amendment fanatics in her publicity. She knows her fan base, she's playing directly to their self-image as Minutemen-type independents who are ready to pick up arms at the drop of a metaphor and defend…

What?

Here's where it starts to get questionable. Just what is it this kind of rhetoric is supposed to be in support of? It's a non-nuclear form of MAD, the suggestion that if people get angry enough they will "take back their government" by armed insurrection. It's the stuff of B movies and drunken arguments on the Fourth of July. Just words, mostly. Until someone decides it's time to act.

I have no doubt Lee Harvey Oswald, Sirhan Sirhan, Arthur Bremer, and Leon Czolgosz were deeply troubled individuals, mentally unstable. I would not be surprised if John Wilkes Booth was the same, although he did work in concert with a number of conspirators. But there are degrees of "troubled" and it's always difficult to predict what anyone will do under the right pressure.

The fact is, we are in a period of the most extreme political ferment we have been in since the Sixties. We've had people march on Washington, we have had well-aired and popularized conspiracy theories treated in certain media as fact, we have a cadre of the worst sort of pundits nationally extolling their audiences to extreme positions on—

What?

Health care.

By early acounts, Mr. Loughner was upset over Representative Giffords' support of health care reform. Upset enough to consider gunning her down. Upset enough to read Palin's "metaphors" of "targeting" Democrats as a call to action. About Health Care Reform.

Yes, I know, it isn't really about health care so much as it is about the role of government in something that has been the bailiwick of private industry for a long, long time. It's about the idea that the government will somehow keep people from getting health care (all the while overlooking that many people are now barred from affordable health care by the very industry funding the jeremiads against the so-called government "take over"). It's about the idea of increasing taxes, about "giving" something to people who don't earn it, about changing our system to a socialist system, about—

All of which is legitimate matter for serious national debate. But this is not a revolution. This is a change of policy and votes were cast. (I find it ironic that all indicators leading up to the final version of what is now derisively labeled "Obamacare" suggested that the majority of Americans not only supported an overhaul but would have approved the one thing the health care industry fought tooth and nail to prevent, namely Single Payer, and now, from the sound of the AM stations and the Limbaugh Brigade you would think no one had supported anything of the sort except a few "liberal" Democrats in Congress. We are allowing ourselves to come under siege over what is, by any metric of popular will, a non-issue. What? The fact that Republicans swept a Democratic majority out of the House in 2010? Two things to remember—that was over the economy, namely unemployment, and that majority won with roughly 23% of the eligible vote. In other words, they didn't win so much as Democrats stayed home from the polls and lost.)

Multiple ironies—Gifford is a gun rights advocate. She is a self-styled Blue Dog Democrat, a moderate to conservative politician. She beat a Tea Party challenge—barely—because she is more or less mainstream in Arizona. This was not an enemy in anything but party affiliation.

More ironies—Judge John Roll was killed in the shooting. He was chief justice of the U.S. District Court in Arizona. He was a Bush (senior) appointee and by all lights a conservative.

This is not now a liberal-conservative matter. Sarah Palin and the Tea Party crowd are not conservatives. George Will is a conservative. These people are not conservatives. They are reactionaries who have decided to use the conservative base as their vehicle to ride rough-shod over American sentiments. All they understand is "taxes are bad" and "anything that limits my right to make millions is wrong." Or some combination of the two.

The philosopher Hegel characterized certain people as "clever" rather than intelligent. He noted that there are those who exhibit the symptoms of intelligence, but in fact it is not true intelligence but a kind of animal cleverness masking as intelligence. Shallow people who speak well and can manipulate people and systems, but who seem to, upon examination, have no real understanding of cause and consequence beyond getting for themselves what they want. You might say amoral, but I think that misses the point. They do what they do in order to obtain for themselves and nothing else matters. Sociopaths fit this description. They fail ultimately because they really don't give a damn about the consequences of their actions—and part of their cleverness is a facility at spinning what they do to free themselves of any responsibility. The current crop of big-mouthed right-wing ideologues fall into this handily. They seem not to understand—or possible care—that when you flash a red cape in front of an angry bull, something is going to break. If the bull is standing in a china shop at the time…

We are perilously close to becoming a closed society. We already do not listen to each other if we have differing opinions. We are becoming so entrenched in our own viewpoints, with the help of a magnificently balkanized media, that we cannot see where we are tripping over general principles in our groping after being right. Growing up, I remember an admonition from my parents that would seem apt in this instance: If you can't play well with your toys, you don't deserve them.

I have personally found the rhetoric of the right wing disturbing and sometimes reprehensible since the Eighties. Exemplified by Rush Limbaugh, they have developed a canon of malign vitriol aimed at anything that strikes them as left or liberal or, more recently, in the least conciliatory to differing viewpoints. They have staked their claim and made it clear they will be intolerant of any kind of bipartisanship. The fact that the Republican Party has aligned itself with these people is a tragedy, because it has become a tar baby they are becoming increasingly bound to. But it is not Congresses responsibility to counter them. This is not a question of what our elected officials will do to tone down the venom, but what we will do.

My advice? Stop listening to these assholes.

I can't put it more civilly than that. The Rush Limbaughs, Glenn Becks, Sea Hannitys, and Bill O'Reillys of our media landscape do not have our best interests at heart. They are demogogues. Insofar as there is any kind of media conspiracy, it is for one purpose only, to increase ratings and therefore marketshare, and this kind of petty, sub-intellectual reductio ad absurdum does that very well. Get people pissed off and they develop a taste for it. They are no different in this regard than the Jerry Springers and all their feuding, pathetic, fame-for-fifteen-minutes-at-any-cost "guests" and as a source of information and erudition in support of a democracy they are worse than useless. Stop feeding the animals. Tune them out.

I know this advice will not matter to those—like Mr. Loughner—who are addicted to the apocalyptic visions generated by that kind of rhetoric. It's not information to them, it's the drug for their particular monkey. But for the rest of us? We can do better.

Final irony for this post. Christina Taylor Greene, the nine-year-old who was killed? She was born on 9/11.

Congratulations, Sarah. You have us devouring our own.

[image error]

January 4, 2011

So Right It's Wrong

Recently, Justice Antonin Scalia shot his mouth off about another bit of "social" judicial opinion and managed to be correct to a fault again. Here is the article. Basically, he is of the opinion that if a specific term or phrase does not appear in the Constitution, then that subject is simply not covered. Most famously, this goes to the continuing argument over privacy. There is, by Scalia's reasoning (and I must add he is by no means alone in this—it is not merely his private opinion), no Constitutionally-protected right to privacy.

As far as it goes, this is correct, but beside the point. The word "private" certainly appears, in the Fifth Amendment, and it would seem absurd to suggest the framers had no thought for what that word meant. It refers here to private property, of course, but just that opens the debate to the fact that there is a concept of privacy underlying it.

The modern debate over privacy concerns contraception and the first case where matters of privacy are discussed is Griswold v. Connecticut, 1965. That case concerned the right of a married couple to purchase and use contraception, which was against the law in that state (and others). The Court had to define an arena of privacy within which people enjoy a presumed right of autonomous decision-making and into which the state had no brief to interfere. Prior to this, the Court relied on a "freedom of contract" concept to define protected areas of conduct. Notice, we're back in the realm of property law here.

People who insist that there is no "right to privacy" that is Constitutionally protected seem intent on dismissing any concept of privacy with which they disagree, but no doubt would squeal should their own self-defined concept be violated. Therein lies the problem, one we continue to struggle with. But it does, at least in Court tradition, come down to some variation of ownership rights—which is what has made the abortion debate so difficult, since implicit in it is the question of whether or not a woman "owns" her body and may therefore, in some construction of freedom of contract, determine its use under any and all circumstances.

Scalia would love to overturn Roe v. Wade and I have no doubt his pronouncement that women do not enjoy protection from discrimination in the Constitution is part and parcel of his desire to see the Constitution set in the same kind of stone as the Ten Commandments—unchanging, implacable, unadaptable. Arguing that because something isn't listed in the Constitution is an attempt to dismiss a priori any Court decisions that might address changed social conditions with which he doesn't agree.

The Fourteenth Amendment addresses discrimination against citizens. So, are not women citizens? Of course they are, and Scalia likely would not argue they weren't. However, they, like certain minorities, are citizens with specific attributes that make them in some ways separate from others. At least, in theory. Does, for instance, the Fourteenth Amendment protect men from sexual discrimination? It should, but the question would arise if men can be discriminated against on the basis of gender—at least, in a specific and nonuniversal way. In other words, can a man be discriminated against on the basis of his genital configuration and its implications the same way a woman can suffer discrimination?

Scalia, as a strict constructionist, would like to believe that the framers intended that the Constitution never alter in its meaning. This is impossible since context inevitably plays a role, and since times have changed and brought with them all manner of social adjustments not foreseen or even desired by the founders, his dismissals on these grounds of specific terminology are silly and even a bit pathetic. Harry Blackmun wrote, in Roe, "The right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment's concept of personal liberty…or…in the Ninth Amendment's reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy." I think the same can be argued for any presumed protection against discrimination on any basis.

Everyone, even, apparently, Justices on the Court, seem to forget the Ninth Amendment.

But he does make a good point, that it is the Legislature's job to enact laws to cover these things. The purpose of the Supreme Court, at its simplest, is merely to vet these laws according to the Constitution. If the Court, however, has already pronounced on a concept, why is it people seem content to sit back and assume that the matter is closed? Shouldn't laws have been enacted in the wake of Roe v. Wade to seal that right in legislation even more concretely than has emerged from a decision which could very well be overturned?

January 1, 2011

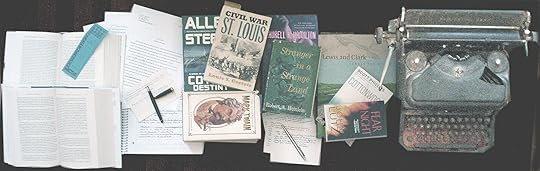

That Book Is Finished…2010

I read, cover-to-cover, 72 books in 2010. I've read more in other years and considerably less in still others. It's an average of six books a month, which, given all the other stuff I read (and write) is a fair amount.

The last one was Ian McDonald's River of Gods, which I'd been putting off. I love Ian McDonald's work, but I am way behind. I, at least, cannot read him quickly. His lines are such that require attention, appreciation. I have half a dozen others on my shelf to get to.

Among others of note, I read Michael Chabon's Kavalier and Clay, which so wonderfully captures the essence of an age that I can't recommend it too strongly, especially to all those mothers poised to toss out their children's comic book collection when they aren't looking (although such parents might be disappearing by now). I also finally got around to reading Connie Willis's Doomsday Book, which can be heart-rending.

I found an obscure book called Faust In Copenhagen by Gino Segri, which recounts the history of the physicists gathering at Neils Bohr's house before WWII, and explores the relationships between the 20th Centuries greatest physicists.

It was a big year for mysteries. I read a string of Ross McDonald, who I consider an underappreciated master—all the strengths of both Hammett and Chandler, few of the weaknesses. Laurie R. King and Rex Stout. I read a few older SF novels I'd either never picked up or had forgotten.

Oh, yes, and the brand new biography of Robert A. Heinlein by William Patterson. Not to be missed.

2010 was also the year I decided to reread all of Dickens. Didn't make a huge way through, but I will be continuing that in 2011.

2011 will probably be an apparently low reading rate year. I intend to read some very fat books waiting for me. I have two large Thomas Pynchon novels I want to get through, more Dickens, the newest Iain M. Banks, and I have some large history books I need to get through. (Right now, though, I'm reading a Cara Black mystery, Murder on the Isle de St. Louis—so much for fatness.)

I also have a couple of my own novels to finish, so that will require research, especially for the second book of my alternate history. I'm going to have to schedule things carefully as I may find myself back in day job la-la-land.

Anyway, I hope everyone had a safe and happy New Year's party last night and that 2011 will be magnificent for everyone.

December 27, 2010

Thoughts On The End of 2010

I may start doing this every year. I've been trying to write some posts about some of the more recent events in politics, but I keep following my arguments into a kind of WTF cul-de-sac. Watching the last four months has been amazing. Not in a good way. Just dumbfounding by any measure. So maybe it will work better if I just do a summary of my impressions of what has happened this past year.

I think I'll say little about my personal situation. It is what it is. Like many people, the upside is hard to find. To reiterate what I said a couple posts back, though, I am not in dire straits. Uncomfortable, but not desperate.

I should remark on the Lame Duck Congress Marathon of Epic Legislation. I can't help being impressed. Obama said he wanted Congress to do with Don't Ask Don't Tell, to repeal it legislatively, and not have it end up as a court-mandated order. I can understand this, especially given the rightward shift of the judiciary. But the way in which he went about it seemed doomed and certainly angered a lot of people who thought he was breaking a campaign promise. (The puzzling lunacy of his own justice department challenging a court-led effort must have looked like one more instance of Obama backing off from what he'd said he was going to do.) I am a bit astonished that he got his way.

A great deal of the apparent confusion over Obama's actions could stem from his seeming insistence that Congress do the heavy lifting for much of his agenda. And while there's a lot to be said for going this route, what's troubling is his failure to effectively use the bully pulpit in his own causes. And the fact that he has fallen short on much. It would be, perhaps, reassuring to think that his strategy is something well-considered, that things the public knows little about will come to fruition by, say, his second term.

(Will he have a second term? Unless Republicans can front someone with more brains and less novelty than a Sarah Palin and more weight than a Mitt Romney, probably. I have seen no one among the GOP ranks who looks even remotely electable. The thing that might snuff Obama's chances would be a challenge from the Democrats themselves, but that would require a show of conviction the party has been unwilling overall to muster.)

The Crash of 2008 caused a panic of identity. Unemployment had been creeping upward prior to that due to a number of factors, not least of which is the chronic outsourcing that has become, hand-in-glove, as derided a practice as CEO compensation packages and "golden parachutes," and just as protected in practice by a persistent nostalgia that refuses to consider practical solutions that might result in actual interventions in the way we do business. No one wants the jobs to go overseas but no one wants to impose protectionist policies on companies that outsource. Just as no one likes the fact that top management is absurdly paid for jobs apparently done better 40 years ago by people drawing a tenth the amount, but no one wants to impose corrective policies that might curtail what amounts to corporate pillage. It is the nostalgia for an America everyone believes once existed that functioned by the good will of its custodians and did not require laws to force people to do the morally right thing. After a couple decades of hearing the refrain "You can't legislate morality" it has finally sunk in but for the wrong segment of social practice.

I don't believe the country was ever run by people of significantly higher moral purpose. There have always been two courts along those lines, one comprised of those who know how to aggressively and successfully capitalize and those who set policy and take care of the interests of those who are not so inclined or skilled at the art of fiscal rape. The business sector, while it would like to see itself as made up of morally-inclined people, has always been willing to greater or lesser degrees to ignore moral principle if it became too costly. They were blocked in practice by those in the other camp, who were able to do what they did because the country, frankly, was flush enough to afford principles.

That's the story, anyway. A bit facile, though there are elements of truth in it. One thing the Left has always been a bit chary of admitting is how big a role affluence plays in the policies it would prefer to see in place. One of the reasons communism always fails historically (just one—I stipulate that there are many reasons communism fails) is that it emerges victorious in poor countries that simply can't sustain it in any "pure" form. (Russia included. While Russia may be materially rich in resources and potential, it was poorly run, horribly inefficient at any kind of wide distribution, and structurally backward. Marx, for his part, believed Russia one of the worst places to start his "workers' revolution." He preferred Germany and, yes, the United States.) This may be why we are so reflexively frightened of communism and its cousin, socialism—all the examples of it we have seen in practice are examples of destitute people, a destroyed middle class and elite stripped of all the material prosperity we value, replaced by a cadre of comfortable bureaucrats. (It suggests that communism is an unlikely system for "raising" standards of living, but might be applicable once a certain level is achieved. This presumes, of course, the other problems with it are solvable.)

At a gathering recently, amid the conversation about all the other ills of the planet, I heard the declaration (again) that we are in a post capitalist world. And I thought (and subsequently said), no, we're not. Because its natural successor has not emerged. We're right in the middle of a capitalist world.

The economic history of the 20th Century can be summed up as a contest between two ideas—collectivism and capitalism. Around the fringes of both systems, hybrids developed. It became clear in the 1930s that capitalism is deeply flawed and requires management, not of the sort supposedly provided by The Market, but of the sort provided by an enlightened social structure that can put the brakes on excesses. Communism, it can be equally argued, gave up on any attempt to institute Marxist methodology, opting for a form of autocratic collectivism that lumbered along like a drunk troll for most of the century, never achieving much of anything for the so-called Masses. If the best one could say of the Soviet Union through all that time was that the people were better off than they had been under the Czars, that frankly isn't saying much. While true, it begs the question why it couldn't do better than the West.

It could also be argued that during the period between 1930 and the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union, we managed our system in such a way as to guarantee a viable counterexample to the soviet system. Which meant a growing, prospering middle class and progressively more inclusive social justice. Civil Rights progressed as much from the self-evident morality of its assertions as from a profoundly uncomfortable recognition that apartheid systems are too easily compared to what happened in Nazi Germany and continued at a lower activity throughout the world to any and all minority groups. To show ourselves superior to Them, we couldn't countenance separate but equal nonsense, so there was movement on both extremes—the street and the halls of power.

With the end of the Soviet Union, there was a sharp understanding (valid or not) that on some level "we" had won. Our system proved superior. We were "better" than they were, at least ideologically.

Which apparently for a certain sector meant we could stop fooling around with all these hybrid systems that utilized partial socialist controls and put roadblocks in the way of capitalist excess. Victory meant the aspect that seemed to make us superior would work even better if we stopped pretending we needed regulations. If the rest of the world would just adopt our system, everyone would be better off. We shouldn't confuse the issue with concessions to non-capitalist ideas.

(You can kind of see this in the Reagan years. It's obvious in hindsight with the increased spending in military R & D and the 600 ship navy and the development of other technologies under DoD auspices, that the Reagan philosophy—tactic, I should say—was to spend the bastards into penury. There is ample evidence that this is exactly what happened. We forced the Soviet Union to respond with their own increased spending, and this exposed their systemic weakness. While our military spending has rarely gotten anywhere near 10% of GDP, the Soviet Union was never under it. Indeed, toward the end, they were spending more than 30% of GDP on the military, a crushing burden, wholly unsustainable. When all their best tech was brushed aside in the first Iraq War, it must have demoralized them profoundly. The collapse came shortly thereafter.)

Since Reagan we have seen a consistent, grinding war on anything that does not support a strictly market-based capitalist methodology. It has now reached the point where we seem to be cannibalizing our own efforts at social justice in order to fuel an expanding private sector frenzy for…

For what? An expanding private sector frenzy for an expanding private sector? Acquisitiveness for the sake of acquisitiveness? It appears sometimes that we are laying up stores of wealth as if preparing for a siege. But a siege against what?

There are (arguably) two things that have made the United States a model to be emulated. Aside from all the other ideas that inform our sense of national identity, two concrete notions have been at the heart of our success as a country. The first is an idea of social equality. In spite of the suspicions many of the Founders had toward the masses, they embraced a basic belief that individuals are not innately better or worse than each other. This was, of course, an Enlightenment-inspired denial of aristocracies, that birth plays no part in individual merit. Even though this idea was unevenly applied and took couple of centuries to manifest for a majority, it was there from the beginning. The people had to live up to the idea, which is usually how such things transpire. It was a powerful idea and would have come to little if not for the second idea, which is that we are entitled to be safe in our property. That no one may take what we legally possess away arbitrarily and we have a right to defend our belongings in court and by legislation. This has allowed for the eventual development of a large and politically powerful middle class which, to greater or lesser degrees, is socially porous, largely because of the first idea. (Even in the worst days of segregation there have been wealthy blacks, and often in sufficient numbers to constitute a parallel middle class and entrepreneurial resource.)

In fits and starts, this has worked well for us over two hundred plus years. Not without cost, though. Such as those times when the two ideas turn on each other and conflict.

This has not been the only period when that has happened. Our history is strewn with the corpses of such conflicts. We have see-sawed back and forth between them. Usually the property side of the conflict wins. When the equality side wins, though, the gains are amazing.

So what about 2010?

It would seem to be a mixed bag, tilted (naturally) toward the property side. But then the last-minute repeal of Don't Ask Don't Tell would seem to be a check in the justice column. Overall, the deployment of forces seem clear enough, and the skirmishes have taken tolls on both sides. But what's the goal? What, in the parlance of wartime diplomats and theorists, does victory look like?

Globalization has brought about a fundamental shift in corporate culture, at least in the United States, which has made explicit what had always been potential and implicit at a certain level, namely that capitalist endeavor is not patriotic. The foregoing of as much profit as possible is not consistent with nationalist sympathies and although I'm sure many an entrepreneur would like to think otherwise, the track record since Reagan has been clearly in the other direction. The outsourcing of American jobs alone should serve as example for this.

What has risen in place of substantial people doing the right thing for their country even if it costs them is a severe kind of quasi-religious patriotic substitute which at base serves to tell those who are paying the cost of this fact that it is their patriotic duty to "man up" and live with it and to vote largely against their own self-interest in order to preserve a distorted idea of Americanism. We have seen a resurgence of a social Darwinism that was never valid and lost ground during the heyday of middle class enlightenment in the post World War II booms. The G.I. Bill underwrote a massive educational effort that gave people who never before had access the intellectual tools to recognize nonsense when they saw it and act against the norm, pushing back at the major corporations and a business ethic that required servitude rather than equitable participation on the part of the labor force. Two things have worked to undo those gains. The first was the matriculation of those very middle class successes into the positions of power that traditionally would have kept them out and over time they have become the people they once worked against. The other has been a severe and consistent gutting of liberal education.

At the aforementioned party there were gathered a number of academics. I heard a lot of complaining about cutbacks and one in particular was going on about how her department was under siege. One need not look far to see that universities and colleges are all scrambling for funding and a lot of what seems to be on the chopping block are courses that fall under the classical liberal arts. If the course is not geared toward making a buck for the student immediately upon graduation, the sentiment seems to run, then what good is it?

But it's not just that. Even legislatively we have seen assaults on the sciences. The most recent is this from Oklahoma. State Senator Josh Brecheen has introduced legislation to force Creationism to be taught in public schools, claiming that in the interest of teaching science "fully" all viewpoints should be taught or both should be removed. This is hardly the first of these, nor will it be the last, but it shows a clear trend that is profoundly anti-intellectual, consistent with a tradition is America that derides education and promotes a faith-based approach to the world. By faith-based I do not mean necessarily religious, although that is certainly a large part of it. No, I mean a kind of fatalistic nationalism that suggests that simply because we are who we are we need nothing more. Americans are just naturally superior. In this model, education—too much education—erodes that essential nature and renders us susceptible to all manner of non-American ideas.

There is a fundamental idiocy in this attitude. It also seems counter to every other aspect of essential Americanism, basically that one never settles, that more is always preferable, that excess is the basis for sufficiency. How does less education square with any of this?

Back in the heyday of the great Red Scares, a political tactic evolved that equated intellectualism—mainly academic intellectualism—with Marxism and thus rendered learning suspect. Certainly learning has a leftist character, Liberalism being an apparent property of education. While this is not true in the specific (I defy anyone to make the case that William F. Buckley was uneducated, anti-intellectual, or even provincial), it does seem that the Right is represented by a less-than-stellar cadre of the intellectually challenged. The spokespeople for the Tea Party are a singularly deficient lot, not least of which is Sarah Palin, who manages to declare her contempt for the intellect every time she makes an utterance. The majority of frontline assailants on education are all self-styled conservatives and the debacle of school board absurdities and text book crisis sometimes seems to spring wholly from Texas and its consistent statements of solidarity with grassroots stupidity.

It is more difficult to generalize when one knows more about a subject. Ignorance is the benefactor of bigotry, stereotyping, and ideological myopia. To preserve their hegemony over what they perceive as the true American landscape, it behooves the Right to curtail education wherever possible.

Why? How does this make any kind of sense?

It makes sense in exactly the same way that the marrow-deep rejection of Evolution by many among this same group makes sense, as a way of denying change. To freeze an essential identity in amber seems all important. To draw a circle around a set of defining characteristics and say "this is what it means to be an American" seems the chief aim of the new nativists. And anyone who doesn't fit within those definitions or challenges their patriotic relevance is to be cast out, cut off, rendered mute. That would be anyone who might suggest business as usual has to change.

I see this as a long arc of historical trending. After World War II, the United States was in an enviable position as a kind of savior of civilization. We were the envy of much of the world, even if much of the world resented us and denied that it very much wanted to be us. As long as there was a clear enemy—the Soviet Union and a perceived threat of encroaching communism—we maintained an identity for ourselves that acted as a kind of ideological and social glue. Whatever else we may disagree with among ourselves, we knew we didn't want to be Them.

But that's gone now. The decade of the 1990s was a period of adjustment. There were problems, but not the kind of iconic Good vs. Evil paradigms that had driven us for half a century. It was a time when we should have realized that what we needed to do was learn to manage, not dominate. And in order to do that effectively, we had to open our minds to wider understanding.

Which, of course, let in all manner of ideas and influences that are Not American.

2010, it seems, was a year in which the lineaments of the coming conflict were more clearly defined. Issues over immigration, secrecy, taxation, distribution of wealth, and civil rights are played a part across the battlefield. Overshadowing all else, though, is the financial crisis and the unemployment rate. Congress was blamed for not fixing it, but really, what could they do? Even if Obama had stood firm about the Bush tax cuts and forced Congress to let them expire on the wealthy, exactly what would that have done for the employment problem? The Republicans keep saying that tax cuts fuel investment, but in the last 30 years we have not seen that to be the case, at least not in terms of people. That extra money finds its way into dividend checks and off-shore accounts, not in higher employment. The other claim is that small business is the real generator of higher employment and that seems to be true, so how does that square with cutting taxes on the top two percent? It doesn't. This is a class issue. That extra tax revenue would go toward paying down the deficit, but it would likely not add a single job.

There is a savage equation in business. A company has little control over most of the expenses incurred—rent, material, energy, all that is fairly rigidly fixed. The only expense where most businesses have any kind of flexibility is labor. Either cut salaries or cut numbers of employees. For small to medium-sized businesses, this is a fairly straightforward calculus—one employee equals salary plus maybe health benefits and the concomitant taxes. For larger firms, it's more complicated—one employee equals salary plus health benefits plus ancillary insurance benefits plus retirement package plus bonus packages plus ancillary taxes. It's a larger sum at a certain level. (Consider auto workers, who may have been making upwards of 60K in salary, but received an addition 50 to 70K in perks, pension promises, etc.) Outsourcing to compete globally becomes a matter of serious money. Even if you take away the egregious compensation packages for upper management, these numbers remain and they are a real concern.

This a direct result, however, of the kind of civilization we run. We are a consumer culture. The More More More demand to keep the economy expanding has resulted in exactly this kind of problem. In order to provide the goods that fuel that growth at a cost people can afford, costs of manufacturing must be kept down. But we've been buying the whole world's production at some level for 50 years now and in order for us to have the money to keep doing that, we have to derive income from somewhere that enables us to maintain, and if the world cannot afford what we make or offer…

Which does not, of course, justify the pillage of American industry that we have seen take place or the obscene transfers of wealth from the public sector to private hands. This has all been done in the name of self-preservation by those who, as I suggested at the beginning of this, are no longer able to afford their otherwise self-proclaimed patriotism. They have somehow defined themselves as America and for all the rest of us? Well, we are welcome to make our own fortunes if we can, but they are removing their sense of responsibility from us.

Before I go on, one other number must be added to the above calculus. The Census has just come out. We have almost 309 million people here now. By comparison, in 1970 there were a bit over 203 million. I chose 1970 because that was a year in which one could clearly see American power and prosperity across the greatest extent of the population. American cars were still the top sellers, American industry still the envy of the world, the American worker the highest paid, most skilled, our educational system on its way to becoming the jewel in the crown. We had just put men on the moon, the future looked to be imminent in so many sparkling and wondrous ways, and we were experiencing a surging liberal commitment to inclusiveness. Nixon was about to create the EPA and the NEA. In spite of the blight of Vietnam, we were doing great. The top 5% economically owned only 14% of the wealth.

Add an additional hundred million people to that, all of whom have had the same expectations of increasing wealth and prosperity, and ask yourself if it is reasonable to have expected anything other than disappointment. Numbers matter.

The world has changed. Easy to say, difficult to understand why that makes a difference. In the face of everything that has changed since 1970, does it make sense to try to maintain a national identity rooted in the 1940s?

I have some thoughts on that score, but I think I'll save them for another post. I will say that I do not see a slide into oblivion as inevitable. But to prevent it will require something progressives have lacked since Reagan—a clear vision.

December 18, 2010

New Gallery

I'd intended leaving the Zenfolio galleries alone for a while and just upgrade some of the images in them, swapping out less wonderful stuff for more. But digging around my various storage boxes this last week I found a cache of negatives and transparencies that represent some of my better work from back in the day. So I've been working all week to put up a new gallery—here.

As I've said elsewhere, my main thing in photography is black & white, but apparently I did quite a lot more color work than I remembered. Odd, that. You do the work, you'd think you would remember. Most of these images are from 35mm, a mix of Kodachrome and Ektachrome. The last four images, however, in the gallery are from 4 X 5 transparencies. Like this one:

What I love about this format is the detail and the lushness of color. But there's something else about it that has in the past been problematic for me.

It requires patience.

When I learned photography, my father understood something about it that I failed to appreciate for years. He understood that to learn any craft well, you have to go at it constantly, and make myriad mistakes. To get it down right, you throw out 90% of what you do. More. So he fueled me with film and paper. Heedless of cost, I blazed away, roll after roll, print after print, gaining ability gradually by virtue of producing a great deal of garbage. You can do that with 35mm and, to a lesser extent, 120 roll film. I would go out on a "expedition" and shoot ten, fifteen rolls. Most of it forgettable trash. (I heard Ansel Adams comment once that he was good in direct proportion to what he never let anyone see.)

I'm not as disciplined as I would like to be. I have no patience. My friends know this and sometimes shake their heads, both at my lack and by the curious fact that it hasn't prevented me from doing quality work from time to time. Everything I've ever tried to do has required exactly what I do not naturally possess.

4 X 5 enforces patience. The equipment is ungainly and heavy. Setting up a shot takes time. Raising a 35mm SLR to ones eye and snapping off half a dozen shots takes little effort, but framing a shot with a view camera cannot be done with that kind of speed or nonchalance. You get one sheet of film, maybe two. The handling and processing is necessarily cumbersome and it just takes time. After a few lousy shots, you find yourself (if you're any good at all) slowing down, being careful, really looking at what you're shooting. Gradually, glacially, you start developing an appreciation for the frame that, at least in my case, the smaller formats with their ease of blazing away never granted.

Curiously enough, the 4 X 5 image I've been reworking in Photoshop have been the ones requiring the least manipulation. I "got it right" on the shot.

I will probably do one or two more galleries and then see about exhibiting. There are over 400 images in my online galleries now, most of them some of my best work. I have literally thousands of more negatives and transparencies. I'm glad of the chance to display them this way, at least give people a chance to see what I've done.

Oh, a note about image quality. Maybe this is something I simply haven't figured out, but it's a technical annoyance, and I want to explain. I'm doing all my work on a standard monitor. The lab I'm using takes the file when I'm finished and makes a print and so far I have seen on the print what I see on my screen. But I've looked at these images on other screens and some of them, for whatever reason, come up very washed out. I've corrected some of them so get a crisper image on flatscreens, but it's unpredictable. So any of you, if you're looking at these and the picture looks flat or too light, please adjust your screen or take my word for it that a print would look marvelous. I'm still learning this digital thing and I'm sure I'm just doing—or not doing—something basic.

Thanks and enjoy.

December 14, 2010

More Images

Since beginning to work with Photoshop, I've been doing some archaeology. Unearthing slides and negatives buried around the house. For so long I used whatever lab I worked at to produce images that when I finally found myself working entirely at home, I basically dumped my files wherever I found room. Now I'm trying to locate stuff.

Sounds horribly disorganized, I know. That's me, though. Both my parents are methodical, organized, neat people. Me, not so much. I have never been able to maintain an organized environment for any length of time. I have to do major cleaning every so often. (Right now my office is a disaster, having been the place everything from upstairs has ended up during progressive cleanings of the main part of the house. And it's winter and I've moved most of my writing upstairs to save on the heating bill.)

I've been trying to find several pages of 35mm slides now for months. These pages were once intended to be portfolio sheets, representing what I could do. In my imagination, the magnificence of the images was beginning to take on epic proportions. Well, I found them today and that magnificence…well, they ain't bad.

They are quite suitable for manipulation, though, and I've begun the process of making them suitable for whatever may come. For example:

I shot that after dawn one day in September, about 1978 or so. I forget where. I just got in the car and drove and found some back roads. I used to do that a lot. Throw the cameras in the back seat, just tank up and drive, see what I could find.

I was never so much with people, at least I didn't think so at the time, but I've done a lot of fair portraits. But I did like doing the occasional bit of narrative photography. Like this:

(That one wasn't quite that vibrant in the original.)

This has been great fun and I think I'm getting inspired to try exhibiting again. I never pursued that enough. Maybe this time I'll stick to it a bit more tenaciously. I'll say this, with all the material I have in boxes I really wouldn't need to take anymore photographs.

Not to worry. I don't intend to stop seeing. Not by a longshot.

December 8, 2010

Explain It To Me

In the movie Philadelphia, Denzel Washington plays a savvy courtroom litigator whose catch-phrase in front of a jury is "Explain it to me like I'm eight-years-old." It's a great line and maybe I'm looking for that kind of clarity now.

I really don't know what to make of this. Obama—who won election with a very solid majority of the popular vote and a most impressive majority of the electoral—has managed to be reasonable to the point of impotence. He's on the verge of validating every cliche about spineless intellectuals. The man is smart, erudite, has charisma, and can't seem to say no to the Right. It is possible that this is another one of those situations where we the people simply don't know what's going on and cannot therefore grasp the tactics or strategy. Maybe this is cleverness at such a level that it looks clumsy and gutless.

I don't believe that for a second, though. (The only thing that makes any kind of sense in that vein is the idea that he is handing the GOP more and more rope with which to hang themselves. The problem with that is any rope, in order to work in an execution, has to be tied to something substantial on one end.)

Let me be clear up front. I am unemployed. My benefits are nearing an end. I'm annoyed by that but not desperate. We did many sensible things over the last several years. We paid off our house. We never carried a balance on our credit cards. Never. We locked away surplus funds in C.D.s and money markets. We bought a new car only because it was cheaper to do that than to keep paying out a few hundred a month to keep the old one running. We told ourselves no a lot. So when my job went away (I've talked about this before; it was a combination of technological obsolescence and the '08 crash) we were not devastated. We had breathing space.

Many of the unemployed do not.

One major reason they do not is because so many bought into the program sold to them by the very people who are now working to strip them of everything else they have.

One of the far Right arguments against Entitlements runs like this: it's your responsibility to take care of your well being, not the State's. That, in fact, the State stepping in in any way to alleviate circumstances brought about by personal irresponsibility (lack of savings, buying on credit, relying on a job that might not be there in ten years) fosters an environment of dependence and undermines the work ethic of the population, creating a welfare state with hundreds of thousands of dependent, lazy people.

This is nothing new. Herbert Hoover expressed exactly these arguments in 1929 as the reasons for refusing direct aid to the catastrophically unemployed. He was afraid that if people got used to sucking off the government teat, they would never go back to work, because, you know, people are fundamentally lazy and will not work if given half a chance.

Which kind of flies in the face of the other Great American Myth of Our Character, that of self-reliant, self-motivated, hard-working, independent people. Both of these views cannot be true, and any halfway serious look at the history of labor in this country shows that the contradiction is entirely in the minds of the greedy or morally myopic. People traditionally hate being dependent for handouts. Most—the vast majority—will go off any kind of assistance as soon as they can find viable work. People are not fundamentally lazy. Idleness makes most people crazy.