Mark W. Tiedemann's Blog, page 86

April 10, 2011

April 8, 2011

A Short Bit About School

There's a scene from that marvelous film, The Dead Poets Society, in which Robin Williams playing teacher John Keating has a brief conversation with Mr. Nolan, the headmaster of the school played by Norman Lloyd, about the purpose of his job.

"I thought my job was to teach them to think," says Keating.

"Not on your life," Mr. Nolan snaps back. "They can learn that in college."

Or something like that. You get the point, anyway.

I just finished reading John Taylor Gatto's thick, data-packed screed on American public schools, The Underground History of American Education. Gatto taught in New York City for 30 years and the year he achieved teacher-of-the-year status, both citywide and statewide, he resigned, fed up finally with fighting a losing battle against a system he declares page after page in this book to be fundamentally malign.

Not that the people who either set it up or run it are bad people—they did what they did and do what they do because they believe in it. And, Gatto stresses, like all true believers, their vision supersedes the reality in which they find themselves.

I found a lot in this book with which to disagree. Gatto's history is right on the borderlands of conspiracy theory. He mentions the masons a few times and once at least accompanied the reference with a suggestive "I wonder what that is all about" line. But he insists this was never done with ill-intent in mind.

Ill intent or not, the result was a system that does not educate, by and large, except by accident. It is a system that chews up idealistic teachers and students on a daily basis because neither realize what exactly it is they are there to do. The system knows, has it built into its basic make-up, and after a century and a half of accrued inertia, the system cannot change. Not easily and not effectively. Those who charge the windmill get tossed thoughtlessly and sometimes crushed. He details instances where perfectly fine teachers have been summarily fired or forced to resign because they elected to do what they thought they were supposed to do instead of what was required of them and the further infuriating instances of teachers and administrators who resignedly continue doing things they know won't work because they want their pension and sinecure.

So what is it that he suggests schools do?

To my surprise, it turns out to be what I've been suggesting for decades.

I've written about this before, but in this context it's worth repeating. I hated school. Loathed it. Practically from the first year on. And it was a weird hatred because I would return every fall determined to like it, to get something out of it. This is something my parents likely would not believe, since from their point of view I wasted my time in school. But I showed up every year hoping something good would happen. It did, occasionally. One or two of my teachers were actually pretty good. But in toto the 12 years was a dreary, mind-numbing, frustrating experience…and I didn't know why!

Learning was never a problem for me. I picked things up quickly. Once learned, however, I wanted to move on. The class, however, stayed stuck making me prove over and over again that I knew what I already did—and then occasionally making me feel like I really didn't know it. Homework completely dismayed me. Some of it, true, I wasn't very adept at—I didn't do well in arithmetic (although I can do percentages in my head, as well as multiply and do some rudimentary fractions—a career in photography is impossible without some math skills, at least the way I practiced it)—but other things, once the teacher said I knew it, I was ready for the next thing. Which didn't happen.

I was reading ahead of my grade practically from the beginning (I entered kindergarten knowing how to read, albeit my main reading was comic books) and that often was met with the kind of disapproval from my teachers that's hard to pin down. I knew by their attitude and sometimes their actions that I was doing something wrong, but I for the life of me couldn't understand what.

And then of course there was the social aspect. I was bullied from 1st grade to 8th. There was, I soon learned, nothing that would be done about it by the teachers.

Looking back on it now, I can characterize it handily—school was a prison. I had to be there, locked in a room with other prisoners who didn't like being there, and the sociology of the playground was in its much milder way the sociology of the prison yard. Students had no power except over other students and it was exercised in cruel but, once the circumstances are clear, perfectly understandable ways. This also explained why there was such antagonism toward "good students"—they were seen as suck-ups, people who were trying to curry favor with the bosses and make an escape "for good behavior."

Some schools were worse than others. There were public schools in my childhood everyone knew were bad places to go. No learning of any worth took place in them and the main requirement was to be tough.

My experience in school is consistent with Mr. Gatto's diagnosis—public schools are not intended to educate but to socialize. They were established to take kids out of the home and turn them into "useful citizens." Useful to whom and for what changes from time to time, but when you recognize the immense contributions of men like Henry Ford and John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie to the establishment of modern public schooling, you start to get a hint. When I went to Roosevelt High School I was told that it was a traditional "blue collar" school—which meant it was there to turn out factory workers for local St. Louis industries. Some of the class selections made by the older counselors on behalf of students—who by then didn't care all that much, school was school, what difference did it make what they had to take—reflected this idea.

Although at the time it made little real sense because the culture at large had changed during the Sixties and most of this was done by rote, because it had always been done, and wasn't leading the students anywhere useful, even by the questionable standards of the early 20th Century.

One of the most telling statements in Gatto's book concerns the era of court mandated overhauls and their many failures. "The problem [I'm paraphrasing] is not that all the money failed to fix the system, but that no one realized that the system wasn't broken, not by its own metrics. it did what it did very well and all that money just gave it more to do the same with."

In those places and schools where someone realized that the way things were being run was fundamentally flawed, real change happened. But these instances are rare.

You have to ask a basic question: in the instance of a situation like Garfield High School in East L.A. where a dedicate educator, Jaime Escalante, took dead-end kids and taught them to do calculus, why can't this happen everywhere? Escalante proved that it wasn't a lack of intelligence on the part of the students. If anything, they were brighter than their better-off counterparts, possibly because just surviving require a raw intelligence honed to a sharper edge. So what is it?

Kids know instinctively when they're being handed a bad deal. After three years in many schools, the light is said to go out in many kids' eyes. By then they realize that it was all a game—they aren't there to learn, they are there to be turned into consumers. Maybe they can't describe it that way, but they know they're being handed a bill of goods. So the system becomes a nanny system, designed to get them to adulthood pliant and cooperative.

Gatto goes much farther. I am not so convinced as he is of the precision of the process. And the fact is, real learning does happen here and there, even within this cockamamie system.

What did I do? I paid little attention in class unless something was going on that interested me. I took charge of my own education, and believe me that was not the best idea. But no one stopped me. I ended up my senior year cutting two and three days a week. Most of those days I spent in the local library, a few blocks up the street from school, reading for five or six hours. It was a wholly unguided regimen, haphazard and chaotic—but I read a lot of good books. Gradually over time I was fortunate enough to find people who, all unknowingly, helped build a framework inside which all that reading turned into something coherent.

I agree the public school system as it stands in many places today probably ought to go away. It does not serve the people attending. But I have a profound antipathy for the current political cries for its demise—they have nothing to recommend to put in its place and because the system is not what we need doesn't mean we don't need one.

April 1, 2011

Because I Still Like Black & White…

…this is an important test of the new camera. How well does it do without color?

There are so many controls built into the camera itself, that I can virtually forgo Photoshop—at least until I learn all the ins and outs of the device itself. But I did do this image in color and turned it B & W in Photoshop.

On Being Fooled

Okay, it's April 1st. We all know what that means. I have myself played an occasional prank in years past, but tend not to as a matter of principle.

See, I don't care much for being teased. Lots of reasons, but a big one has to do with having been not particularly cool for a very significant part of my childhood, which meant not being "in" on a lot of the current really important stuff that all my peers thought was the basis of timeless significance. So I was an easy mark when it came to being tagged in pranks and April Fool's Day was a big one for being made to feel, well, stupid.

Fast forward. I still don't care for being teased. As a result, I usually don't tease other people. Can't take it, don't dish it out, even though I recognize that it actually isn't a big deal anymore and in many instances it is a demonstration of affection. I've learned to accept it in small doses, but there comes a point past which I start to bristle and…

Well, it's been likewise a long time since I was taken in by an April Fool's hoax, and this morning I bought a good one, hook-line-and-sinker fashion, and then compounded it by letting everyone know.

Arrogance being far worse than humility, we should all be gracious about being reminded how not sharp we often are. You take your humility where you can get it and let it be a lesson, etc etc etc. Happy April Fool's Day, everyone, and may it all end with a laugh and better assessment of where we are with ourselves.

Oh, the prank? This one here.

March 28, 2011

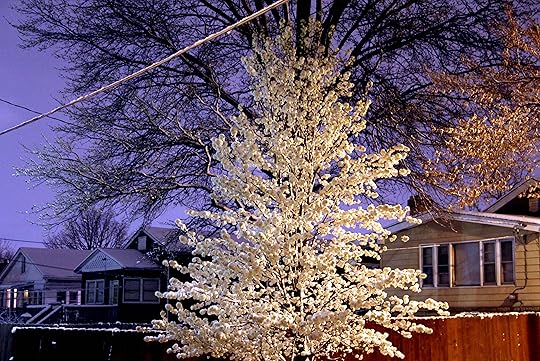

First Image

I've been dutifully reading the manuals for the new camera, even though in some cases it is high order calculus to my primitive mind. Still, I wanted to show something for the expense and the effort, so…here is the first image, from Saturday evening.

Whenever possible, I like to start with something DRAMATIC!

March 26, 2011

Biting Bullets

Okay, so today was the day. The Day. After procrastinating for many reasons, both rational and just perverse, Donna and I plunked down our plastic and walked out of ye olde camera emporium with my new camera. I've been talking to people, some of them extremely knowledgeable (internet wave to Jennifer—"Thank You!"), and reading blogs and consumer reports and websites and agonizing and today it culminated in A Purchase.

Was a time, mind you, that this would have been the cause of a couple of days of decision-making. I used to be one of the Go-To people about matters photographic. If I needed a new piece of equipment, the only question was, could I afford it this week or did I have to wait a few more weeks.

But this was a chunk of change, an issue of moment, and on something of which I am less than qualified. After having dipped into as much printed material as I could stand, I ultimately had to go talk to a real live salesperson and Make A Decision.

Rob at Schiller's Camera was very helpful a couple of weeks back. Salesman after my own heart. He answer my questions, didn't push, took out camera after camera for comparison, and new his stuff. After a couple hours, we'd narrowed the field to two, and after going over all the relevant stuff afterward, I made my choice.

A Canon EOS 60D. My new machine. I've spent most of today reading the owner's manual and playing with it. It will take a long time to master all the stuff this thing will do, but I can already take a photograph with it and this will only improve. (I'm an intuitive kind of guy when it comes to this sort of thing. Take it out and road test it, carry it as an extension of my limbs and eyes for months on end, snap away thousands of frames, learn the mechanism until I can make the necessary adjustments reflexively. Just there's a lot more to learn on this than I'm used to—and it will make movies.)

I haven't put up any new images on the Zenfolio site in a bit. It will still be a while before I do—I have to download the new software for the file transfers, get used to how these files work in Photoshop, and actually, you know, take some new pictures I think worth showing The World. But the next new gallery will be from this beauty. It's an impressive camera. It feels right. I think it's the beginning of a beautiful relationship.

March 25, 2011

"I do not like Home School and Ham…"

Ken Ham is the head of Answers In Genesis, an organization that promotes and perpetuates the Creationist view that the Earth is less than ten thousand years old, that homo sapiens sapien trod the same ground at the same time as dinosaurs, the the story of Noah is literally true, and that evolution is All Wrong. He's an Australian and a biblical literalist. He built the Creation Museum in Petersburg, Kentucky, in 2007. Check the link for an overview by an (admittedly) biased source, but for simple clarity is hard to beat. It is a fraud of research, flagrantly anti-science, and laughable in its assertions (in my opinion).

Ken Ham is one of the more public figures in our current national spasm of extreme religiosity. He's attempting to have built another show-piece in Kentucky, a theme park based on Noah and the Flood. The problem with this, however, is that tax dollars are being used in its construction and it is a blatantly religious enterprise.

In the meantime, Ken Ham and Answers In Genesis have recently been disinvited from a conference on homeschooling. There are multiple ironies in this, especially since, on the face of it, Ham and these particular homeschoolers would seem to be sympatico on the issues.

Be that as it may, it prompted me to make a couple of observations regarding this whole phenomenon. According to the Home School Legal Defense Fund, homeschooling is a growing practice.

it is estimated that the annual rate of growth of the number of children being homeschooled in the U.S. is between 7% to 15%. Reports from 1999 determined that approximately 850,000 American children were being home schooled by at least one parent. This number increased again in 2003, to over one million children, according to the National Center for Education Statistics National Household Education (NHES). NHES compiled data showing that in 2007, over 1.5 million children in the U.S. were home schooled.

There are several reasons for this, but the most stated are:

Religious or moral instruction 36%

School environment 21%

Academic instruction 17%

Other 26%

Questions of violence, socialization, academic standards, and related issues play into these decisions. Not all homeschooling is, as is popularly thought, conducted for religious reasons, but certainly religious homeschooling gets the lion's share of the publicity.

I have the same reservations about homeschooling as I have with special private schools that seek to isolate students from the wider community. Despite the problems with "the world" to put an informational barrier between a child and that world can put that child at a disadvantage later. But I can't argue with the sentiment that many public schools are dysfunctional and do a disservice to students. The 17% of the sample opting for homeschooling for academic reasons probably have concerns with which I'd agree.

The more people pull their children out of public education, though, the less incentive there is to fix that system.

I'm torn on this. I'm largely self-educated. But the foundation of my education was laid in public schools (K through 4th in public school, second half of 4th through 8th in parochial school, 9 through 12 in public high school). I had many problems with school when I was in it, and later, upon review, some of those issues I decided were justified. I certainly felt at the time better read than my English teachers. (This was a false impression based entirely on the syllabus they were allowed to teach. I was certainly better read than the syllabus.) There were distortions in all my history classes, some of which I took issue with at the time. The administrative side was annoying and the classes I would have desired to take were either truncated or unavailable. I got most of my education from books read on my own initiative.

But that doesn't mean this is in any way a recommended program for most students. Part of the academic experience is and must be socialization (although I firmly believe most of the problems we have with public education today stem from the fact that in America the primary purpose of school has always been socialization, often at the expense of academics, and we're paying for this unacknowledged fact today).

What profoundly disturbs me about the 36% of those who homeschool for religious reasons is precisely the problem presented by people like Ken Ham. Parents who reject science as an enemy to their religious beliefs do neither their children nor this country any good by isolating their children and inculcating the distorted views presented in the name of some sort of spiritual decontamination. What these parents wish to tell their kids at home is their business—but there is also a vast pool of legitimate knowledge about the world which needs to be taught if these kids are to have any chance at being able as adults to make reasoned and rational choices, for themselves and for their own children and for the society in which they live and work. Few parents have either the time or the training to do this, at least in my opinion, whether they are certified or not, simply because they are only one voice. Much education happens in the crossfire of ideas under examination by many. The debate that happens in a vibrant classroom setting is vital to the growth of one's ability to think, to analyze, and to reason. The by-play that will likely not happen between dissenting viewpoints or between different apprehensions of a topic won't happen in isolation.

Ken Ham tends to bar outside viewpoints when he can. He has a history of banning people from the Creation Museum when he knows they are antagonistic to his viewpoint. In the face of overwhelming evidence, he tries to assert a reality that has long since been shown to be inaccurate. That he was barred from a conference of folks who will then educate their children in those same inaccuracies is an irony of epic proportions. But, as they say, what goes around, comes around.

March 23, 2011

Slogging Through

I've been going through this novel like a reaper, cutting and slashing, removing viscera, changing things around. It's fun so far. The request was to knock between 50 and 100 pages out of the manuscript, which roughly equates to between twelve and twenty thousand words. So far I have flensed the text of seven thousand. This may sound like a lot, but the book was nearly 140,000 to start with, so it can lose a little weight and probably be much better for it.

The weather has been beautiful and since I am working in my front room, by the big picture window, it's been pleasant. At the rate I'm going I ought to have a new draft of the book in a few more weeks. At which point I have a half dozen other things in need of tending.

Meantime, as well, I'm slogging through Paul Johnson's Birth of the Modern: 1815 - 1830. It is the estimable Mr. Johnson's contention that these were the years which gave birth to our modern world, the period during which everything changed from the old system to the new, and, 400 pages in, he's making a good case for it. Of course, any historical period like this is going to have some sprawl. He's had to go back to just prior to the American Revolution and look forward to the Civil War (using a purely American point of reference, even though the book is attempting to be global). I can think of worse markers than the end of the Napoleonic Era for an argument like this and he is certainly one of the more readable historians. Occasionally his observations are a bit surprising, but in the main this is a credible piece of work.

I read his Modern Times a few years ago and found it very useful, even though some of his interpretations of major 20th Century events I found surprising. As always, it is necessary to have more than one source when studying history. Interpretation is a bay with hidden shoals and can be perilous. But this one is a good one.

Just updating. Go back to what you were doing.

March 19, 2011

Rewrites and Retirement

For the next several weeks I'll be engaged in rewriting a novel, one I thought I'd finished with a few years back. One of the frustrating things about this art is that often you cannot see a problem with a piece of work right away. It sometimes takes months to realize what is wrong, occasionally years. You work your butt off to make it as right as possible and then, a few years and half a dozen rejections later, you read it again and there, in the middle of it (sometimes at the beginning, once in a while at the end) is a great big ugly mess that you thought was so clever when you originally wrote it. You ask yourself, "Why didn't I see that right away?" There is no answer, really. It looked okay at the time (like that piece of art you bought at the rummage sale and hung up so proud of your lucky find, but that just gets duller and uglier as time goes on till you finally take it down with a sour "what was I thinking?") and you thought it worked, but now…

This is what editors are for. This is what a good agent is supposed to do. This is the value of another set of eyes.

Anyway, that's what I'll be doing. And I have the time because last week I "retired" from the board of directors of the Missouri Center for the Book. I served for nine years, five of them as president. Per the by-laws, after nine years a board member must leave for a time. This is vital, I think, because burn-out is like that manuscript you thought was so perfect—sometimes it take someone else to notice that everything's not up to par.

During my tenure as president, a few changes were made, Missouri got a state poet laureate with the MCB as the managing organization, and a cadre of new board members revitalized the whole thing. Look for some good programs to come out of them in the next few years.

What I find so personally amazing is the fact that I got to do this. I mean, be president of essentially a state organization. Small budget, sure, but it is connected to the Library of Congress and we do deal with the governor's office and what we do has relevance for the whole state. I started out doing programming for them and for some reason they thought I should be in charge. Well, that's a story for another time. Suffice to say, I have no qualifications (on paper) for that position. None. The first year I got the job I characterized my management approach as throwing spaghetti. Something was bound to stick.

It was an education. And I got to work with some very talented people and made some friends who are inestimable. My horizons were expanded and I was able to play in a sandbox of remarkable potential.

The timing couldn't be better, though. I have this novel to rewrite and, as it is the first part of a projected trilogy, I thought I'd go ahead and finish the second book after I fix the first one. Yes, there are things in the offing which I shan't discuss right now—as soon as I know anything concrete, you will, should you be reading this—and Donna has graciously cut me another several months' slack to get this done. She is priceless.

Meantime, I may be posting here a bit less. Not much. But a bit.

Stay tuned.

March 15, 2011

Epithets

This will be fairly brief. I found myself once again disappointed in a fellow critter. I don't know his name so I can't "out" him, nor would I even if I did. Up until last week, I rather enjoyed encountering him when I walked Coffey—he was always smiling and always had a treat for her. But I am now taking routes at times designed to avoid him.

I thought I'd heard all the racial epithets going around, but he had a new one and as we walked about two blocks together he used it and complained about the people to whom he referred in a general "Them" rant that turned me off.

I grew up in South St. Louis at a time when the city was struggling to come to terms with its racial mix. We had some violence here in the late Sixties and I remember after Dr. King's assassination that several of our neighbors "stood guard" by sitting on their porches with rifles, shotguns, and pistols, "just in case." Just in case never happened, so no one got shot, but the black-white tension was palpable and even today you can feel it despite the fact that St. Louis is becoming a fairly integrated city. It has been a long time since I've heard certain terms out of doors, in mixed groups and I certainly never expected (perhaps naively) to hear a brand new one.

Somehow I never really internalized the bigotry, but I have to confess that at times I felt it, more from those around me than anything from within (although I experienced the first waves of public school integration in the early Sixties and had an event that could very easily have set a pattern of discrimination). My grandmother was a self-righteous racist who talked about a slave-owning branch of the family with a weird kind of nostalgia, but I grew up and got over it and by the time I left high school I simply didn't think that way anymore.

It helps being an outsider from the major groups and cliques.

So when I encounter it now, I am usually startled. I have to shift mental gears to accommodate what I'm hearing and it's always disagreeable at best, often repulsive.

Here's how I think—people can be assholes. Leave it at that. Your ethnic origins have nothing to do with it. White assholes, black assholes, brown, yellow, what have you, assholes are assholes. It is both pointless and ignorant to identify an entire group on the basis of one or two assholes, especially when the salient feature of disregard is a behavioral trait shared by all—an asshole is an asshole. I treat people as individuals. Granted, in certain conversations, general statements of certain groups about common group characteristics can be valid, but none of that is genetic and to conflate race into the mix for the purposes of discrimination or the venting of animosity is childish, crude, and flat wrong.

The thing is—and perhaps this is a generalization, but I'm speaking now of the long list of personal encounters I've had with people who indulge this kind of thing—people who feel compelled to belittle others through the use of epithets are often themselves failures in one way or another and all they're doing is trying to make themselves have value by comparison with those they regard as their natural inferiors.

There are no "natural" inferiors.

I just wanted to say something about this. I find it sad that we still—still—haven't gotten over this, and maybe we never will completely, but damn.