Mark W. Tiedemann's Blog, page 85

May 11, 2011

Invisible Women

I'm taking time out (already) from all the rewriting I have to do to complain and restate a principle.

Here's a lovely little bit of misogyny.

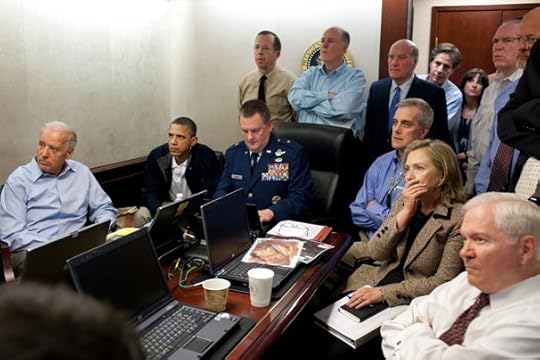

Read the article? A newspaper took the photograph of the ready room where Obama and his cabinet received the news of Bin Ladin's death and photoshopped out the women present. For reasons of "modesty" they claimed. They then apologized but asserted they have a First Amendment right to have done this.

Inadvertently—and I am sure they didn't think about this when they did it—they gave Bin Ladin a small cultural victory out of his own death. The religious view Bin Ladin asserted, supported, and fought for includes the return of women to second class status, to the status of property. By doctoring that photograph, the editors of Di Tzeitung tacitly approved this idea.

Modesty. Really? They erased Hilary Clinton and a staffer in the background. You look at the photograph in question:

Is there any way to look at that and perceive immodesty in the way we usually use the term? I don't see any scanty clothing or alluring, over-the-shoulder glances at the camera. No legs, no cleavage, no hint of sexualization, which is what is normally meant by use of the term, even—especially—within the context of religious censure. This sort of attitude is intended as a guard against titillation and "impure thoughts", but I'm having a hard time seeing anything like that here.

In fact, this has made clear what the real problem is and has been all along. Rules about "modesty" have nothing to do with sex and everything to do with power. Secretary of State Clinton—the Secretary of State of the United States of America, the most powerful nation on Earth, is a woman!—is a female in a position of power. She is the boss of many men. She is instrumental in setting policy, which affects many more men, men she doesn't know and will never know. She wields power and that is what is feared by these—I'll say it because I'm pissed about this—these small-minded bigots.

And in their effort to make sure their daughters never grow up with the idea that they can have power or any kind, not even in the say over what to do with their lives (because they don't even have any say over how they dress, who they can talk to, where they can go, what they can aspire to), these "proper" gentlemen handed Osama Bin Ladin a final supportive fist bump of solidarity. "Yeah, brother, we hated the fact that you blew people up, but we really gotta keep these females in their Place."

Cultural relativism be damned. I'm one hundred percent with Sam Harris on this. Subjugating half the population to some idea of propriety and in so doing strip them of everything they have even while hiding them head to toe and keeping them out of the public gaze is categorically evil. The fact that this is resisted so much by otherwise intelligent people—on both sides of the issue, those who perpetrate it and those who refuse to outright condemn it for fear of being seen as cultural imperialists—is as shameful as the defenders of slavery 150 years ago.

Now, at least, they've made it hard to miss. This wasn't a photograph of some beauty pageant or a spread in Playboy or the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue; this wasn't a still from the red carpet runway at the Golden Globes or the lurid front page of a Fleet Street tabloid. No, this was a photograph of powerful people doing serious work and two of them do not have a penis. This is the issue—power. Women the world over have no say in their lives. They are wives, concubines, prostitutes, slaves. If they wish to change the way they live, they are forbidden, sometimes killed for their ambition. In many places still their daughters have their sex organs mutilated so they won't ever fully experience sexual pleasure and, theoretically, never want to stray from the men who own them. They are denied the vote, denied a voice, denied even the courtesy of Presence in life. They are made background, wallpaper, accoutrements for the men who are set against yielding even a token of consideration toward the idea that "their women" are people.

People who happen to be women. People.

I am sick of this crap. I am sick of people who don't understand the issue. I am sick of the tepid response among people who should see this as an unmitigated evil who won't speak up to condemn it outright. By their reluctance to condemn they allow this sickness to grow in their own backyard. There are groups in this country who but for a few "inconvenient" laws would—and in some cases do—treat women exactly the same way. I am sick of the constant onslaught on family planning services and the idea that women should not be in command of their own bodies. I am sick of the feckless insecurity of outwardly bold and inwardly timid males who are afraid of the women around them, that if these women actually had some choices they would leave. I am sick of men who can find no better use for their hands than to beat women, no better use for their minds than to boast of their manliness, and no better use for their penises than to keep score. I am sick of women who are made to appear at fault for their own rapes because of the way they dress or walk or talk or because they thought, just like real people, they had a right to go anywhere they chose, free of fear. I am sick of seeing the human waste of unrealized potential based on genital arrangement and the granting of undeserved rights and authority based on the same thing. I am sick of being told by people who obviously haven't stepped outside of their own navels that this is what god wants because some preacher or imam or shaman told them and they like the idea that there is someone who can't say no to them no matter how abusive or failed they are as human beings. I am sick of seeing women pay the cost of men deciding for them what they should be.

For those of you who read this and agree, excuse the rant. Shove it in the faces of anyone who gives even lip service to the idea that women are somehow other than and less than males and that maybe a little "modesty" would be a good thing. Modesty in this context is code for invisibility.

Back now to our regularly scheduled Wednesday.

May 10, 2011

Working

I tell hopeful, wannabe writers all the time, when they ask that marvelously optimistic question, "what's the secret to being a writer?" It's a deceptively simple question, because the answer…well, I give the same answer no matter who's asking, but the expectations differ from person to person. I suspect most want to know what the "trick" is, like there's a gimmick, a magician's sleight of hand, a way around the essential thing, which is hard damn work.

But I tell them all: persistence. Those who never make it are those who quit.

Obviously this begs a few questions. What if they have no talent? What if what they're writing has no audience? What if they're subliterate? What if they don't like to read? (This last, while apparently absurd on its face, is nevertheless a more common fact than you might believe—aspiring writers who don't read. I've met 'em, talked to 'em. It's like a photographer saying he doesn't like looking at photographs.)

All of that varies, though. The one single element that binds them all together in their quest is persistence. Persist and you will find out. But if you don't persist, you may never know.

This is what I do. I persist. I refuse to give up. Granted, I have a bit more reason to be optimistic than most, since I have actually published, but that's no guarantee that you will continue to do so. The market is a fey beast, fickle and heartless, and has crushed the souls of many a writer before. But, smart as I am, I'm an idiot when it comes to this, and it seems to finally be paying off a bit.

I have signed with the Donald Maass Literary Agency. This is a fairly big event for me. I've been shopping for a new agent for a long time. This one finally paid off. (My thanks go out to Scott Phillips, who introduced me to the obviously talented Stacia Decker, who then introduced me to the talented Jen Udden, and my thanks to both for taking a chance on my potential.) My last published novel was Remains, back in 2005—almost six years now.

This is not a sale. But this moves me closer to getting back into print than I was three months ago. Both Jen and Stacia have gone over my work, made substantive editorial recommendations, and allowed me to move forward on these books.

I feel very lucky right now.

But also, I have a lot of work to do. I have already rewritten my alternate history, Orleans, per Jen's recommendations, and she's beginning work on the marketing strategy. This morning I talked over The Spanish Bride with Stacia and will set to work on the revisions of that novel in the next couple of days.

I have no problem admitting that I need editorial input. And I like it. When someone who knows what they're doing tells me "You should fix that" and I see what they mean, I'm delighted. (This has changed over the years. Once, all it got from me was a howl of pain—"but I already wrote that one! I want to move on!" But persistence teaches you through experience. If it doesn't, you should find a different career.) With good recommendations in hand, I can make a better book.

So anyway, the bottom line here is that if I am less prolific here in the next few weeks or months, it's because I'm working. I will update as developments occur.

May 2, 2011

Atavistic Pleasure

Since hearing the news this morning I've been trying to find a calm space wherein reason and judgment will allow for a rational response, but for the time being I can't help it.

Osama Bin Laden is dead.

I can't help feeling glad about that. There is an atavistic part of me responds to this kind of thing.

I have a number of other thoughts—for instance, where they finally found him is suggestive of a whole bunch of negative assessments about out "allies" and the uses to which historical fulcrums are put—and there will doubtless be backlash over this, but done is done and I cannot find it in me to feel in the least sorry. He seemed to have become the ultimate in revolutionary narcissists and chose to believe his "wisdom" trumped the lives of all his victims. There has been and is much that is wrong in our relationships with the Middle East, but slaughter frees no one, and where clear heads and earnest consideration are needed to solve problems, terror guarantees their absence.

Burying him at sea was a clever move—there will be no grave to be turned into a new shrine. In the end, he harmed his own people far more than he hurt us, and the last thing this planet needs is another monster elevated to the status of demigod.

What we need to do now is take those sentiments to heart—slaughter frees no one, terror banishes reason—and stop reacting like offended adolescents. We must be careful that we ourselves don't fill the void left by Bin Laden's death with our own self-justified nationalism and continue what we know to be bad policy.

But for now, I'm a little more pleased by this than not.

That's the way I feel. I'll have a more rational response some time down the road.

April 27, 2011

Why Free Marketeers Are Wrong

Paul Ryan and his supporters are trying to sell their spending cut and lower tax program and they're getting booed at town hall meetings. They're finally cutting into people's pockets who can't defend themselves. They thought they were doing what their constituency wanted and must be baffled at this negative response.

Okay, this might get a bit complicated, but not really. It just requires a shift in perspective away from the definition of capitalism we've been being sold since Reagan to something that is more descriptive of what actually happens. Theory is all well and good and can be very useful in specific instances, but a one-size-fits-all approach to something as basic as resources is destined to fail.

Oh, I'm sorry, let me back up a sec there—fail if your stated goal is to float all boats, to raise the general standard of living, to provide jobs and resources sufficient to sustain a viable community at a decent level. If, on the other hand, your goal is to feed a machine that generates larger and larger bank accounts for fewer and fewer people at the expense of communities, then by all means keep doing what we've been doing.

Here's the basic problem. People think that the free market and capitalism are one and the same thing. They are not. THEY ARE CLOSELY RELATED and both thrive in the presence of the other, but they are not the same thing.

But before all that we have to understand one thing—there is no such thing as a Free Market. None. Someone always dominates it, controls it, and usually to the detriment of someone else.

How is it a free market when one of the most salient features of it is the ability of a small group to determine who will be allowed to participate and at what level? I'm not talking about the government here, I'm talking about big business, which as standard practice does all it can to eliminate competitors through any means it can get away with and that includes market manipulations that can devalue smaller companies and make them ripe for take-over or force them into bankruptcy.

There is, in fact, no such thing as a "free" market—you buy your way in, you spend pelf to stay in, and you play the game to keep anyone out that might threaten your ability to grow your market share. The larger the market share you own, the more you can dictate the conditions of the market, which includes prices on goods and services as well as income levels of employees, even whether or not specific communities will be served and how. We have become used to seeing how a company like WalMart can virtually destroy a small community all in the interest of consolidating a given market. Their actions can cause townships to dissolve by forcing employment into a centralized hub and then shutting down any and all competing local businesses, leaving fewer options for the locals. An employer of size can dictate tax levels to towns, even cities, get preferential treatment because of the number of employees and the implicit threat of penury should they leave.

A better descriptor would be Open Access Market. But for that, someone has to be responsible for keeping all the gates open.

This is not a free market.

Free market is a euphemism these days for No Controls.

The more we roll back regulation and the tax base the more the tax base is eroded, because the companies demanding such rollbacks with the implied promise of reinvestment do not follow through—they use the rollbacks and the politicians they have sponsored to acquire greater freedom of action to shift the latent wealth of communities out of those communities and into their hands.

I've mentioned this before and this is the basis on which I recommend a shift in perspective.

Latent wealth. What am I talking about?

It's very simple and any businessman in the business of taking over and dismantling other companies knows exactly how this works. So let's use the example of such a takeover to illustrate the point.

Company A makes, say, chainsaws. They have worked for more than half a century improving their product, according to a more traditional view of how a business should run, which is to set up shop to manufacturing a product and improve it and make it desirable through both quality and, as the business grows, reduction in price. After 50 or 60 years they have reached a level of reputation that is enviable. They make one of the best chainsaws in the world. It's a bit more expensive than other brands, but for good reason—it's a better chainsaw.

Operating this way, the company has learned over the years that their costs are at a certain level. They require a certain skill level among employees, materials have to be of a certain quality, they must do regular maintenance on their physical plant, they have to invest a certain amount in research to continually be on top of potential improvements, and their management has to understand the methods by which they make their product. Along with other expenses, the company has to spend a certain amount to maintain themselves.

For any of a number of reasons, they become vulnerable to a take-over. Maybe it's something as simple as the current owners don't want it anymore. It could be that they went public and the dividends they pay are not high enough to please a significant block of shareholders, so they sell their shares to buyers looking for what is about to happen.

Company B comes along and makes them an offer. Company A sells.

Now, it's possible that what Company B will do is take Company A into its fold, nurture it, and because of Company B's presumably larger customer base or their better business plan they will preserve and save Company A. This happens. There are such Company Bs. But the other scenario is what I'm interested in.

What the shareholders of Company B want is a quick turnaround of high dollar value. Company B goes in and immediately reduces overhead in order to increase the profit margin per unit. They may even lower the price in order to bring it more in line with its cheaper competitors. Relying on the reputation of the Company A chainsaw, this works—people who would not buy one before because it was too expense will buy it now, so sales increase.

But the profit margin is still higher because Company B has reduced the quality control staff to a bare minimum. They have started buying materials from a less reliable but cheaper vendor. They increase the speed of production so more units are going out the door. If this becomes difficult, a program of firing the higher-paid skilled workers begins and replacing them with less skilled, cheaper, more compliant workers. Plant maintenance is cut to the bone. All the money spent on maintenance and probably research is reduced drastically. With substantially less overhead, the profit margin per unit shoots up. The dividends are higher. A small bubble results. The stocks get more actively traded. For a short while Company A looks worth much more than it did before.

All this cutting, though, has a longterm deleterious effect. At some point the ability to produce a reliable product is impaired. They lose their quality edge. Eventually, Company A is manufacturing chainsaws that are no better—and possibly worse—than their cheaper competitors.

While all this is going on, if Company A runs a union shop, union busting is going on in order to force the union into concessions whose aim is basically to force them into compliance with what by now is an obvious program. Workers leave. The employees are occasionally offered early retirement packages. The old workforce is whittled away and replaced. Maybe the union itself is successfully busted. (If this happens in a right to work state, this part is already dealt with because there is no union.)

Finally the plant suffers from the debilitating lack of maintenance and things break down. Consumers lose confidence. Sales begin an inexorable plummet. At this point, Company B either looks for another buyer and shuts it down themselves and sells off the remaining physical assets either as scrap or piecemeal to competitors.

A few people have subsequently made a great deal of money in just a few short years.

What has happened is, Company B has removed all the latent wealth from Company A, converting it directly into short term profits, at the expense of the entity that was Company A. When the dust settles, a certain number of people who once had decent livings working for Company A are looking for other jobs and a source of community stability is gone.

Here is where the tax-cutting Tea Baggers fundamentally misunderstand capitalism.

Capitalism—like any other economic system—is simply a way to organize the latent wealth in a community. The building of a business is an organizing enterprise, a way to bring otherwise disparate elements of a community together and concentrate what till then is only potential in such a way that order is created and the wealth generated is converted into readily distributable and usable forms. That's all. Capitalism has to date simply been the most efficient and productive way to do this because of the nature of its built-in incentives, namely personal profit.

I don't wish to undervalue this. It is very important and very useful. Potential wealth is just that—potential. A group of people can wander around as a loose community on a mountain full of diamonds and still be unable to better their lives because the wealth latent in their presence at that mountain is completely untapped. It is the peculiar genius of capitalism that all this unfocused energy and ability can be identified, organized, and turned into a productive means of utilizing those diamonds. The carrot, of course, is Improvement of individual circumstance.

Like any organizing system, communities require something like this in order to sustain themselves. Looked at this way, you can go all the way back to the days of the Pharoahs and see that all communities had some form of organizing activity that allowed the latent wealth to be converted into a means of improvement. Capitalism basically came along and removed pedigree and privilege from the equation and offered a method whereby anyone could do this and do it in such a way that the greatest efficiency and growth resulted.

What gets lost, however, is the raw materials. We are talking about the latent wealth of a community. Everything that gets converted into—for the purposes of this discussion—money comes from that community in the first place.

In other words, the capitalist comes into a community (or comes out of it) and makes use of what is already latent within that community to build a structure that allows for the efficient use of innate resources—labor, the intellectual skills available, the environment, the social interconnectedness, the material resources available—and in return the capitalist expects a profit. As order emerges out of chaos, there is an ability to improve conditions and generate a certain amount of excess around the growing volume of organization. We call this excess profit and the thing that has made capitalism such a dynamo is the recognition that this excess is for the individual or group of individuals who are most responsible for the work that has been done in organizing, coordinating, and utilizing latent wealth. This incentivizes people to do this work.

I need not go into the endless variety of uses for profit. The more efficient this system is, the greater the apparent amount of this excess.

But it's not really excess. What it is is the unutilized product of the organized work. It is not needed for the work at hand, the allocations of expenses have already been met, and there is this left-over "energy" if you will—but it is still a product of the work done and as such comes out of the community along with everything else.

Capitalism operates on the assumption that this excess may become the personal property of the individual.

In a way, all the salaries paid to the laborer (at whatever level, even if we designate them management) are part of this.

Now here's where it has all gone very wrong.

What has been forgotten is the source of the actual material process—which is the community. A captain of industry can't do much more than imagine the factories and the products and the profits unless the community at large both allows the work and then cooperates with it fully. No matter how you want to dress it up, the Owner is not ever solely responsible for such a creation.

But communities self-identify. Subsequently, we see a situation where community bonds are split artificially in this instance—labor and management, workers and owners.

What we have been witnessing since Reagan began deregulating everything is the actions of a predatory capitalism leeching the latent wealth out of communities businessmen do not regard themselves part of. In exactly the way Company B runs Company A into the dirt and sells off the husk after every dollar of converted wealth is taken out of it. Except this is being done to everyone—towns, cities, states, the country. Regulation must be in place to keep this relationship in balance, otherwise the wreckage left behind after the pillage will support very little.

The power relationship has been unbalanced and reversed. Communities do not exist to serve wealth, wealth is organized and distributed to serve communities.

No one need suggest that capitalism be abandoned. It remains one of the most efficient mechanisms for this process ever developed. But the idea that those who use it best are the sole beneficiaries by moral right of its product is fundamentally in error. This fact needs to be recognized and understood and acted upon before those we have sold our Company A to run us all into penury.

The Tea Party keeps insisting that taxes be eliminated or at least drastically reduced. They assert this out of the belief that taxes restrain business from creating wealth and therefore jobs, at least in its simplest formulation. This is obviously not true as we've been going through repeated cycles of tax reduction since JFK was in office and by the end of the Seventies one thing was clear for anyone to see if they look—as taxes and regulations are reduced, the community at large has lost wealth. Real wages have stagnated, unemployment has gone up, the government has been called upon again and again to fill in where one presumes private enterprise should be providing support. Add to this the clear intention of business to eliminate as much overhead as possible through union busting and outsourcing of jobs and the fact that above a certain level profits have grown exponentially and it ought to be obvious that this strategy contains a serious flaw in logic.

Taxes, when judiciously administered, are the best way to make sure the latent wealth of a community, once organized by capitalist improvement, is not packaged up and removed from that community to the detriment of that community. This is the cost business owes to that community for allowing itself to be used. When this is done in a reasonable fashion, profit remains a motivating factor and the community itself retains the resources to provide for its own health.

Because we are all part of a community. This makes sense on a basic level. What we are allowing to happen now is self-immolation, all for the sake of a broken idea of what we think is ideal.

Now. I would like to ask everyone to stop voting against the general welfare. It should be obvious after thirty years of this that Big Business has no interest in being responsible to anyone other than itself and that has clearly not been working to the benefit of the rest of us.

April 26, 2011

Dead Stuff

This may be social suicide, but I'm going to say it anyway.

I don't like zombies.

Not too thrilled with vampires, either.

I mean—hell, they're dead. Dead. And motivating. The contradiction alone is…

I am tired of zombies, though. And vampires.

In the last several months, I have picked up at least two novels I was very much looking forward to reading because their premises looked really cool. I put both down because zombies got dragged into them, and I thought unnecessarily. Zombies are cool right now, though, and apparently a lot of people like reading about corpses shambling around trying to eat the neighbors. Never mind that they don't seem to move very fast and an octagenarian with a hip replacement could outrun one, but…

Now, I liked Michael Jackson's Thriller. I even liked the zombie dance in it. I thought it was a neat twist on an old theme. But it's an old theme and while even I wrote a story that sort of dwelt on the possibilities of vampirism explaining certain religious rituals, it was a short story and I didn't make a career out of it.

To be fair, I have never been much of a horror fan. I don't find having the crap scared out of me particularly fun. Some do. Certainly a lot of people in my life have had fun scaring the crap out of me, but that's another story. So I was never a wolfman fan or a mummy fan or a Dracula fan or any of that. I could appreciate these things as one time motifs for a specific work of fiction, but to turn them into cottage industries…

I even liked Buffy, but not really because of the vampires and such. I thought it was funny. (And Willow was hot.) Angel not so much.

I find the fannish obsession with dead things a bit disturbing. Necrophilia is not healthy. But each to his or her own, I say. Not for me to judge.

But I do dislike it ruining otherwise good fiction because it's, you know, trendy.

I wouldn't mind having a good explanation for it. I like to understand things. Knowledge is power, after all, and even for the purposes of self defense…

Anyway, there. I've said it. I don't like zombies. And I would really like them not in what appear to be otherwise perfectly good steampunk novels that I would otherwise read with delight.

I do wonder how many others feel the same way…

April 24, 2011

My Obligatory Piece About Ayn Rand

From time to time, here and there, someone brings Ayn Rand up as some kind of role model. Lately it's even in the national news, thanks to the Tea Party and an apparently not very good film of Rand's seminal masterwork, Atlas Shrugged. The uber conservatives now crowding reason out of the halls of congress with their bizarro legislation and their lectures from the floor and on committees about how their toilets don't flush right so why should regulations on light bulbs be passed are the children of the Dragon's Teeth cast randomly by Ms. Rand and her philosophical cult followers. It amazes how people who profess to believe in a philosophy of independent thought can sublimate themselves so thoroughly to the dogmas of that philosophy and claim with a straight face that they are free thinkers on any level. The phrase "more Catholic than the pope" comes to mind sometimes when crossing verbal swords with these folks, who seem perfectly blind to the contradictions inherent in their own efforts. Rand laid out a My Way or the Highway ethic that demanded of her followers that they be true to themselves—as long as they did as she directed.

Ayn Rand's novels, of which there were three (plus a novella/parable I don't intend to discuss here), moved by giant leaps from promising to fanciful to pathetic. There are some paragraphs in any one of them that are just fine. Occasionally a secondary character is nicely drawn (Eddie Willers is possibly her most sympathetic and true-to-life creation) and from time to time there is even a moment of genuine drama. But such bits are embedded in tar pits of philosophically over-determined panegyric that drowns any art there might be.

But then, her devoted fans never read them for the art.

What Rand delivers in both The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged is a balm to the misunderstood and underappreciated Great Man buried in the shambling, inarticulate assemblage that is disaffected high I.Q. youth.

The give-aways in both novels involve laughter. The opening scene in The Fountainhead characterizes Howard Roark for the entire novel, prefiguring the final scene in the novel, which translated to film perfectly in the weird 1947 Gary Cooper thing.

Howard Roark laughed.

He stood naked at the edge of a cliff….He laughed at the thing which had happened to him that morning and at the things which now lay ahead.

Of course, the thing that had happened to him that morning was his expulsion from university for not completing his assignments. You can pretty it up with philosophical dross, but basically he didn't do what he was required to do, instead opting for self-expression in the face of everything else. Hence the misunderstood genius aspect, the wholly-formed sense of mission, the conviction of personal rightness, and the adolescent disdain for authority no matter what.

But his reaction? To laugh.

Any other kid in the same situation generally goes skulking off, bitter and resentful, harboring ill thoughts and maybe an "I'll show you" attitude that may or may not lead to anything useful.

But not a Rand character. They laugh. It's Byronic in its isolated disdain for rules or logic or anything casually human. It's a statement of separation.

It's also just a bit psychotic.

The other scene is from Atlas Shrugged in which Dagny Taggart falls into bed with Henry Reardon. Both are depicted as mental giants, geniuses, and industrial rebels. They are self-contained polymaths who make their own rules. And one of the rules they now make for themselves is that adultery is the only sensible choice for two such kindred beings.

And as they're tumbling into an embrace?

When he threw her down on the bed, their bodies met like the two sounds that broke against each other in the air of the room: the sound of his tortured moan and of her laughter.

Of course, this most poignant moment is preceded by a long paragraph of Dagny explaining to Hank Reardon that she was going to sleep with him because it would be her proudest moment, because she had earned it. It's really rather ridiculous. It's the kind of thing that, if done at all, would most likely occur at the end of an affair, when both parties are trying to justify what they'd done, which is basically commit adultery because, you know, they wanted to.

But it's the laughter that characterizes these two people in these moments. Crossroads for them both, turning points, and what do they do? They laugh. You can't help but read contempt into it, no matter how much explanation Rand attempts to depict them as somehow above it all. For her it's the laughter of victory, but in neither case is there any kind of victory, but a surrender.

Later in Atlas Shrugged Reardon gives her a bracelet made of his miracle metal and upon snapping it closed on her wrist, she kisses his hand, and it is nothing short of a moment from Gor. Dagny gets traded around through the novel until she ends up with John Galt, and no matter how much Rand tries to explain it, the scenarios she sets up for each transition turn Dagny into a groupie. She becomes by the end of the novel the prize each of them men gets when they've done a particularly impressive trick.

Rand attempts to portray their interactions (if you can call them that—really, they're more contract negotiations, which means Rand owes an implicit debt to Rousseau) as strenuously righteous achievements. No one just has a conversation if they're a Rand hero, they declaim, they negotiate, the issue position statements. They are continually setting ground rules for the experience at hand, and while maybe there's something to this (we all indulge this sort of thing, from earliest childhood on, but if we tried to do it with the kind of self-conscious clarity of these people nothing would ever happen), it serves to isolate them further. They are the antithesis of John Donne's assertion and by personal fiat.

Only it isn't really like that.

The problem with being a nerd is that certain social interactions appear alien and impenetrable and the nerd feels inexplicably on the outside of every desirable interpersonal contact. People like Rand attempt to portray the group to which the nerd feels isolated from as deliberately antagonistic to the nerd because they sense the nerd's innate superiority. This is overcomplicating what's really going on and doing so in an artificially philosophical way which Rand pretends is an outgrowth of a natural condition. The messiness of living is something she seeks to tame by virtue of imposing a kind of corporate paradigm in which all the worthwhile people are CEOs.

As I said, it's attractive to certain disaffected adolescent mindset.

But it ain't real life.

I have intentionally neglected the third novel, which was her first one—We The Living. I find this book interesting on a number of levels, one of the most fascinating being that among the hardcore Randites it is almost never mentioned, and often not read. The reasons for this are many, but I suspect the chief one being that it doesn't fit easily with the two iconic tomes. Mainly because it's a tragedy.

We The Living is about Kira Argounova, a teenager from a family of minor nobility who comes back to Moscow after the Revolution with the intention of going to the new "classless" university and becoming an engineer. She wants to build things and she knows that now is her chance. Prior to the revolution, she would never have been allowed by her family or social convention—her destiny was to have been married off. That's gone now. We never really learn what has become of the rest of her family, but we can guess. And Kira is intent on pursuing her dream.

But she can't. Because she is from minor nobility, she soon runs afoul of the self-appointed guardians of the Revolution, who oust her from the university just because.

She ends up a prostitute, then a black market dealer. She becomes the lover of an NKVD agent and uses him. She is already the lover of a wannabe counter-revolutionary who can't get his game on and ends up in self-immolation. The NKVD agent self-destructs because of the contradictions she forces him to see in the new state and Kira goes from bad to worse and finally makes an attempt to escape Russia itself and ends up shot by a hapless border guard at the Finnish border. She dies just inside Finland.

It is a strikingly different kind of novel and it offers a glimpse of where Rand might have gone had she stuck to this path. Sure, you can see some of the seeds of her later pedantry and polemic, but the bulk of the novel is heartfelt, an honest portrayal of the tragedy of dreams caught in systemic ambivalence.

One can understand the source of Rand's fanatic love of the United States—she grew up under the early Soviets, and there's no denying that this was a dreadful system for a bright, talented, intellectually-bent young woman—or anyone else, for that matter—to endure. The freedom of the United States must have been narcotic to her.

But she fundamentally misunderstood the American landscape and identified with the glitzy, large-scale, and rather despotic "captains of industry" aspect rather than the common citizens, the groundseed of cooperation and generosity and familial observance and openness that her chosen idols took advantage of rather than provided for. She drew the wrong lessons and over time, ensconced within her own air-born castles, she became obsessively convinced that the world was her enemy and The People were irredeemable.

Sad, really. Sadder still that so many people bought into her lopsided philosophy.

She made the mistake so many people seem to make in not understanding that capitalism is not a natural system but an artifice, a tool. It is not a state of being but a set of applications for a purpose. It should serve, not dictate. She set out a playbook which gave capitalism the kind of quasi-legitimate gloss of a religion and we are suffering the consequences of its acolytes.

However, it would seem the only antidote to it is to let people grow out of it. There's a point in life where this is attractive—I read all these novels when I was 15 and 16 and I was convinced of my own misunderstood specialness. But like the adolescent conviction that rock'n'roll is the only music worth listening to and that the right clothes are more important than the content of your mind, we grow out of it.

Some don't, though. And occasionally they achieve their goals. Alan Greenspan, for instance.

And even he has now admitted that he was wrong. Too bad he didn't realize that when he was 21.

April 22, 2011

Between

I completed a massive rewrite the other day and sent it out. When I say massive, I mean big, a whole novel. There's a lot riding on this and I find myself fidgety and on edge in a way I haven't experienced in a long time. It was an older book, one I thought (mistakenly, as it turned out) was done, complete, just fine. What I found was proof that I need a good editor.

But the work is done and it's out the door and all I can do now is wait for the yea or the nay. Not sure what I'll do if the answer is…

Everytime I get to the end of a major project, I find myself at sixes and sevens, loose ends need chasing down, and I don't quite know what to do with myself. Formerly, some of this time and excess energy was spent by going to a job. That's not an option now. I used to go through a frenzy of cleaning house as well and I will likely do some of that today. But later. This morning, after breakfast, I opened Photoshop and noodled with a few images. Having multiple creative streams is a good thing when you're in a situation like this. The above image is one result and I've decided to sandwich this post between two pictures.

Not to be melodramatic, but in some ways I'm facing a turning point. I have to do Something. Almost 30 years ago I set my goal to become a published writer. Much to my amazement, I succeeded, but the effort birthed the desire to do this as my main work, which means I have to keep publishing. Whether we like it or not, we need money to live, otherwise I could quite contentedly (I think, I tell myself) write for my own pleasure and use this medium or others to put the work out and not worry about income streams. But it's not just the income and anyone who writes for a living knows very well that this is true. After a five year spurt of publishing intensity, things have ground to a virtual halt. There are a number of reasons for this, some of them entirely my fault. But I have to turn it around and soon or walk away.

I'm not at all sure I can and remain whole.

Of course I have this older art, photography. I can, with some difficulty, get a freelance business up and running. There's music, too, although I am years from the kind of proficiency that would adequately supplement my income. Tomorrow I'll be playing guitar at the anniversary party of the business of a friend. An hour or so of my ideosyncratic "stylings" as a favor. For fun.

These spans of dry time between projects require distraction lest I tumble into a tangle of self-pity and despair. It never lasts, I'm not so stoically romantic that I can sustain the dark time of the soul connected to artists denied their opportunity. For better or worse, I seek happiness and am constitutionally incapable of living long in depression. If not today, then by Monday I'll be at work on something new or a new twist on something old and I'll be trying again.

And for the time being I feel like the rewrite just finished is pretty good. I have confidence in it. I will let you all know if the news is…

Well, whatever it is.

Have a good weekend.

April 17, 2011

The Fruits of (Fun) Labor

For whatever reason, I put 32 images in each of my online galleries. Don't know why, I just do. No cosmic significance, it just worked out that way when I started, so I'm sticking to it.

That said, I have filled a new gallery with work done since I began using my new camera. I'd like to share with everyone. So here:

As always, all these images are for sale. Click on the one you think you'd like, copy and paste that URL into an email message to me, and tell me what you'd like. I'll send you a quote.

Soon as I get the current manuscript done and out the door, Donna and I have tentatively scheduled a long day on the road to get some other shots besides stuff just around our house. But I've always been a firm believer in looking closer at what there is right to hand. It's amazing what you can find even in your own back yard.

Enjoy.

April 14, 2011

The Future of Space Commercials (or is that Commercial Space…?)

This is very cool. This is the promo video for the next generation of privately-built low-earth orbit heavy lifters, the Falcon Heavy from SpaceX. What I like about this is, basically, it's a commercial for a spaceship. Appropriately weighty music track, great imaging, and the brag lines are like any other commercial for any other industrial product.

When I was a kid reading stories about the future of space travel, it didn't occur to very many of the authors that there would have to be advertising to go along with their services. One of the many things not quite gotten right. Also, many of them were pretty vague about who was actually running the space lines. Oh, some of them alluded to luxury cruises, which implied a Cunard-style commercial firm behind them, but it was not often put front and center, so you could be forgiven for believing it would all be government-run, financed, built, etc.

Well, one of the basic ideas behind NASA was always that it should be a research and development program to create the technologies that one day folks like Virgin and SpaceX would use to create private enterprises. It looked for a long time like that was never going to happen. Space travel is really damn expensive and the pay-back on investment is really long-term. In the quarterly-statement cycle into which most businesses are locked these days, it seemed unlikely any visionaries would scrape together the funding to, you know, build it. But that's happening now, although sometimes it feels like a snail's pace. But it's happening. Who knows? It might be less than a decade before a commercial shuttle starts docking at the ISS.

The commercials, though—that's where NASA really dropped the ball back when they were a force to be reckoned with. Heinlein chewed them out for not having a decent PR department and I still believe part of the reason they get so little support is that during the whole moon-landing decade, everything you saw on tv was boring. (It's unfair, I know, but consider it from the average 12-year-old's viewpoint comparing the endless, static "simulations" of the Gemini and Apollo vehicles in orbit to any then-current SF show, like…Star Trek…? What would you rather watch? NASA bored themselves out of popular support.)

But it didn't die and it's still doing great cutting-edge stuff, but now it's fulfilling the high-end expectations of its purpose and we're getting cool stuff like SpaceX, Virgin Intergalactic, and others. Ad Astra!

April 13, 2011

Post Manuscript Depression

Sort of. I have just completed a marathon session (about four weeks straight) of disassembling and revising a novel I thought I'd completed years ago. The rewrite came at a request. I may have news, but not now. That's for later.

I don't know about others, but when I finish a big project like that, I tend to have a day or two of complete confusion. I don't know what to do with myself. For several years, I cleaned house afterward, which occupied the time I might spend brooding, used whatever left-over energy from the writing process, and performed a domestically useful job. But I've been home now for almost two years, the house is fairly clean as a matter of course, which leaves only major jobs to do (my office ceiling needs repair, I have to build new bookshelves again, and the garage still requires attention) and I frankly don't want to do any of that.

After the work is done, I tend to feel depressed. Not gloomy, just enervated. This morning I straightened out my desk, cleaned up some unused files on the computer, and puttered. I have to walk the dog yet and see about lunch. Much of the day will be spent waiting.

Waiting for what? Good question. There are phone calls I'm waiting for, but none specifically for today. Emails as well. I came close, I think, to botching something yesterday of some importance because I got tired of waiting. Waiting requires a state of mind I do not possess. I can act like I possess it, play-act the role of the calm, confident individual to whom things will, by dint of zen gravitas, inevitably come. But that's not me, not really, not ever.

I have a model kit that has been waiting for me to build it for several years now. Yes, I said years. I acquired it because I had it as a kid and really liked it—the H.M.S. Victory, Lord Nelson's flagship—but I didn't build it then.

There were three model kits I clearly remember having as a child that I did not assemble. My dad did. There was a balsa wood and paper bi-plane that actually flew (a Jennie, if I recall correctly); a beautiful 1933 Mercedes Benz touring car; and the Victory. I didn't build them because my dad wanted to see them "done right." So he built them while I watched.

Well, watched some of the time.

Admittedly, he did an amazing job on all three. When he finished, they were spectacular. He even did the rigging on the Victory with black thread (the kit at the time did not include the rigging, but he found a guide for how it should look). I really liked that ship. So I always thought I'd someday get that kit and build it myself. Just to say I'd done it.

I'm a sloppy craftsman. I admit it. I have no patience for fine, meticulous detail work. And model kits used to puzzle me no end because I have never found joy in the actual building, which is what you're supposed to discover. The "purpose" of such things is to teach the appreciation of assemblage, of patience, of doing a job of some duration and doing it well.

Screw that, I wanted the finished product. I would probably have been happier if I could have bought the damn things already completed. But they didn't come that way, so…

My models were always characterized by poor joins, glue runs, and, if I painted them, bad finish. But I was happy—I had the thing itself!

So why am I a writer? (Or a photographer, for that matter?)

Because I want the finished product and I want it to be just so. I have to do it myself. I have forced my natural lack of patience into a straitjacket of control that occasionally slips, but which I yearly gain in competence. Because ultimately the only way to get what I want is to practice something for which I have no natural affinity.

Which leads me to my current depression. What I ought to do is sit down and carefully consider my next project. My impulse is to just open a file and start banging away on a new story. But I don't have one that appeals to me just now and I have all this other stuff that needs doing.

And I know that, although this rewrite is "finished," there will likely be corrections once Donna gets through the manuscript.

It might be a good time to start that model kit. But I have no place just now to work on it. I need to clean a space for that. Bother. Might as well just walk the dog and eat lunch.