Jeremy Keith's Blog, page 62

May 8, 2019

Timing out

Service workers are great for creating a good user experience when someone is offline. Heck, the book I wrote about service workers is literally called Going Offline.

But in some ways, the offline experience is relatively easy to handle. It’s a binary situation; either you’re online or you’re offline. What’s more challenging���and probably more common���is the situation that Jake calls Lie-Fi. That’s when technically you’ve got a network connection …but it’s a shitty connection, like one bar of mobile signal. In that situation, because there’s technically a connection, the user gets a slow frustrating experience. Whatever code you’ve got in your service worker for handling offline situations will never get triggered. When you’re handling fetch events inside a service worker, there’s no automatic time-out.

But you can make one.

That’s what I’ve done recently here on adactio.com. Before showing you what I added to my service worker script to make that happen, let me walk you through my existing strategy for handling offline situations.

Service worker strategies

Alright, so in my service worker script, I’ve got a block of code for handling requests from fetch events:

addEventListener('fetch', fetchEvent => {

const request = fetchEvent.request;

// Do something with this request.

});

I’ve got two strategies in my code. One is for dealing with requests for pages:

if (request.headers.get('Accept').includes('text/html')) {

// Code for handling page requests.

}

By adding an else clause I can have a different strategy for dealing with requests for anything else���images, style sheets, scripts, and so on:

if (request.headers.get('Accept').includes('text/html')) {

// Code for handling page requests.

} else {

// Code for handling everthing else.

}

For page requests, I’m going to try to go the network first:

fetchEvent.respondWith(

fetch(request)

.then( responseFromFetch => {

return responseFromFetch;

})

My logic is:

When someone requests a page, try to fetch it from the network.

If that doesn’t work, we’re in an offline situation. That triggers the catch clause. That’s where I have my offline strategy: show a custom offline page that I’ve previously cached (during the install event):

.catch( fetchError => {

return caches.match('/offline');

})

Now my logic has been expanded to this:

When someone requests a page, try to fetch it from the network, but if that doesn’t work, show a custom offline page instead.

So my overall code for dealing with requests for pages looks like this:

if (request.headers.get('Accept').includes('text/html')) {

fetchEvent.respondWith(

fetch(request)

.then( responseFromFetch => {

return responseFromFetch;

})

.catch( fetchError => {

return caches.match('/offline');

})

);

}

Now I can fill in the else statement that handles everything else���images, style sheets, scripts, and so on. Here my strategy is different. I’m looking in my caches first, and I only fetch the file from network if the file can’t be found in any cache:

caches.match(request)

.then( responseFromCache => {

return responseFromCache || fetch(request);

})

Here’s all that fetch-handling code put together:

addEventListener('fetch', fetchEvent => {

const request = fetchEvent.request;

if (request.headers.get('Accept').includes('text/html')) {

fetchEvent.respondWith(

fetch(request)

.then( responseFromFetch => {

return responseFromFetch;

})

.catch( fetchError => {

return caches.match('/offline');

})

);

} else {

caches.match(request)

.then( responseFromCache => {

return responseFromCache || fetch(request);

})

}

});

Good.

Cache as you go

Now I want to introduce an extra step in the part of the code where I deal with requests for pages. Whenever I fetch a page from the network, I’m going to take the opportunity to squirrel it away in a cache. I’m calling that cache ���pages���. I’m imaginative like that.

fetchEvent.respondWith(

fetch(request)

.then( responseFromFetch => {

const copy = responseFromFetch.clone();

try {

fetchEvent.waitUntil(

caches.open('pages')

.then( pagesCache => {

pagesCache.put(request, copy);

})

)

} catch(error) {

console.error(error);

}

return responseFromFetch;

})

You’ll notice that I can’t put the response itself (responseFromCache) into the cache. That’s a stream that I only get to use once. Instead I need to make a copy:

const copy = responseFromFetch.clone();

That’s what gets put in the pages cache:

fetchEvent.waitUntil(

caches.open('pages')

.then( pagesCache => {

pagesCache.put(request, copy);

})

)

Now my logic for page requests has an extra piece to it:

When someone requests a page, try to fetch it from the network and store a copy in a cache, but if that doesn’t work, show a custom offline page instead.

Here’s my updated fetch-handling code:

addEventListener('fetch', fetchEvent => {

const request = fetchEvent.request;

if (request.headers.get('Accept').includes('text/html')) {

fetchEvent.respondWith(

fetch(request)

.then( responseFromFetch => {

const copy = responseFromFetch.clone();

try {

fetchEvent.waitUntil(

caches.open('pages')

.then( pagesCache => {

pagesCache.put(request, copy);

})

)

} catch(error) {

console.error(error);

}

return responseFromFetch;

})

.catch( fetchError => {

return caches.match('/offline');

})

);

} else {

caches.match(request)

.then( responseFromCache => {

return responseFromCache || fetch(request);

})

}

});

I call this the cache-as-you-go pattern. The more pages someone views on my site, the more pages they’ll have cached.

Now that there’s an ever-growing cache of previously visited pages, I can update my offline fallback. Currently, I reach straight for the custom offline page:

.catch( fetchError => {

return caches.match('/offline');

})

But now I can try looking for a cached copy of the requested page first:

.catch( fetchError => {

caches.match(request)

.then( responseFromCache => {

return responseFromCache || caches.match('/offline');

})

});

Now my offline logic is expanded:

When someone requests a page, try to fetch it from the network and store a copy in a cache, but if that doesn’t work, first look for an existing copy in a cache, and otherwise show a custom offline page instead.

I can also access this ever-growing cache of pages from my custom offline page to show people which pages they can revisit, even if there’s no internet connection.

So far, so good. Everything I’ve outlined so far is a good robust strategy for handling offline situations. Now I’m going to deal with the lie-fi situation, and it’s that cache-as-you-go strategy that sets me up nicely.

Timing out

I want to throw this addition into my logic:

When someone requests a page, try to fetch it from the network and store a copy in a cache, but if that doesn’t work, first look for an existing copy in a cache, and otherwise show a custom offline page instead (but if the request is taking too long, try to show a cached version of the page).

The first thing I’m going to do is rewrite my code a bit. If the fetch event is for a page, I’m going to respond with a promise:

if (request.headers.get('Accept').includes('text/html')) {

fetchEvent.respondWith(

new Promise( resolveWithResponse => {

// Code for handling page requests.

})

);

}

Promises are kind of weird things to get your head around. They’re tailor-made for doing things asynchronously. You can set up two parameters; a success condition and a failure condition. If the success condition is executed, then we say the promise has resolved. If the failure condition is executed, then the promise rejects.

In my re-written code, I’m calling the success condition resolveWithResponse (and I haven’t bothered with a failure condition, tsk, tsk). I’m going to use resolveWithResponse in my promise everywhere that I used to have a return statement:

addEventListener('fetch', fetchEvent => {

const request = fetchEvent.request;

if (request.headers.get('Accept').includes('text/html')) {

fetchEvent.respondWith(

new Promise( resolveWithResponse => {

fetch(request)

.then( responseFromFetch => {

const copy = responseFromFetch.clone();

try {

fetchEvent.waitUntil(

caches.open('pages')

then( pagesCache => {

pagesCache.put(request, copy);

})

)

} catch(error) {

console.error(error);

}

resolveWithResponse(responseFromFetch);

})

.catch( fetchError => {

caches.match(request)

.then( responseFromCache => {

resolveWithResponse(

responseFromCache || caches.match('/offline')

);

})

})

})

);

} else {

caches.match(request)

.then( responseFromCache => {

return responseFromCache || fetch(request);

})

}

});

By itself, rewriting my code as a promise doesn’t change anything. Everything’s working the same as it did before. But now I can introduce the time-out logic. I’m going to put this inside my promise:

const timer = setTimeout( () => {

caches.match(request)

.then( responseFromCache => {

if (responseFromCache) {

resolveWithResponse(responseFromCache);

}

})

}, 3000);

If a request takes three seconds (3000 milliseconds), then that code will execute. At that point, the promise attempts to resolve with a response from the cache instead of waiting for the network. If there is a cached response, that’s what the user now gets. If there isn’t, then the wait continues for the network.

The last thing left for me to do is cancel the countdown to timing out if a network response does return within three seconds. So I put this in the then clause that’s triggered by a successful network response:

clearTimeout(timer);

I also add the clearTimeout statement to the catch clause that handles offline situations. Here’s the final code:

addEventListener('fetch', fetchEvent => {

const request = fetchEvent.request;

if (request.headers.get('Accept').includes('text/html')) {

fetchEvent.respondWith(

new Promise( resolveWithResponse => {

const timer = setTimeout( () => {

caches.match(request)

.then( responseFromCache => {

if (responseFromCache) {

resolveWithResponse(responseFromCache);

}

})

}, 3000);

fetch(request)

.then( responseFromFetch => {

clearTimeout(timer);

const copy = responseFromFetch.clone();

try {

fetchEvent.waitUntil(

caches.open('pages')

then( pagesCache => {

pagesCache.put(request, copy);

})

)

} catch(error) {

console.error(error);

}

resolveWithResponse(responseFromFetch);

})

.catch( fetchError => {

clearTimeout(timer);

caches.match(request)

.then( responseFromCache => {

resolveWithResponse(

responseFromCache || caches.match('/offline')

);

})

})

})

);

} else {

caches.match(request)

.then( responseFromCache => {

return responseFromCache || fetch(request)

})

}

});

That’s the JavaScript translation of this logic:

When someone requests a page, try to fetch it from the network and store a copy in a cache, but if that doesn’t work, first look for an existing copy in a cache, and otherwise show a custom offline page instead (but if the request is taking too long, try to show a cached version of the page).

For everything else, try finding a cached version first, otherwise fetch it from the network.

Pros and cons

As with all service worker enhancements to a website, this strategy will do absolutely nothing for first-time visitors. If you’ve never visited my site before, you’ve got nothing cached. But the more you return to the site, the more your cache is primed for speedy retrieval.

I think that serving up a cached copy of a page when the network connection is flaky is a pretty good strategy …most of the time. If we’re talking about a blog post on this site, then sure, there won’t be much that the reader is missing out on���a fixed typo or ten; maybe some additional webmentions at the end of a post. But if we’re talking about the home page, then a reader with a flaky network connection might think there’s nothing new to read when they’re served up a stale version.

What I’d really like is some way to know���on the client side���whether or not the currently-loaded page came from a cache or from a network. Then I could add some kind of interface element that says, "Hey, this page might be stale���click here if you want to check for a fresher version." I’d also need some way in the service worker to identify any requests originating from that interface element and make sure they always go out to the network.

I think that should be doable somehow. If you can think of a way to do it, please share it. Write a blog post and send me the link.

But even without the option to over-ride the time-out, I’m glad that I’m at least doing something to handle the lie-fi situation. Perhaps I should write a sequel to Going Offline called Still Online But Only In Theory Because The Connection Sucks.

May 2, 2019

Frameworking

There are many reasons to use a JavaScript framework like Vue, Angular, or React. Last year, Nicole asked for some of those reasons. Her question received many, many answers from people pointing out the benefits of using a framework. Interesingly, though, not a single one of those benefits was for end users.

(Mind you, if the framework is being used on the server to pre-render pages, then it’s a moot point���in that situation, it makes no difference to the end user whether you use a framework or not.)

Hidde recently tried using a client-side JavaScript framework for the first time and documented the process:

In the last few months I built my very first framework-based front-end, in Vue.js. I complemented it with a router, a store and a GraphQL library, in order to have, respectively, multiple (virtual) pages, globally shared data and a smart way to load new data in my templates.

It’s a very even-handed write-up. I highly recommend reading it. He describes the pros and cons of using a framework and using vanilla JavaScript:

I am glad I tried a framework and found its features were extremely helpful in creating a consistent interface for my users. My hope is though, that I won���t forget about vanilla. It���s perfectly valid to build a website with no or few dependencies.

Speaking of vanilla JavaScript… the blogging machine that is Chris Ferdinandi also wrote a comparison post recently, asking Why do people choose frameworks over vanilla JS? Again, it’s very even-handed and well worth a read. He readily concedes that if you’re working at scale, a framework is almost certainly a good idea:

If you���re building a large scale application (literally Facebook, Twitter, QuickBooks scale), the performance wins of a framework make the overhead worth it.

Alas, I’ve seen many, many framework-driven sites that are most definitely not that operating at that scale. Trys speaks the honest truth here:

We kid ourselves into thinking we���re building groundbreakingly complex systems that require bleeding-edge tools, but in reality, much of what we build is a way to render two things: a list, and a single item. Here are some users, here is a user. Here are your contacts, here are your messages with that contact. There ain���t much more to it than that.

Just the other day, I saw a new site launch that was mostly a marketing site���the home page weighed over five megabytes, two megabytes of which were taken up with JavaScript, and the whole thing required JavaScript to render text to the screen (I’m not going to link to it because I don’t want to engage in any kind of public shaming and finger-wagging).

I worry that all the perfectly valid (developer experience) reasons for using a framwork are outweighing the more important (user experience) reasons for avoiding shipping your dependencies to end users. Like Alex says:

If your conception of “DX” doesn’t include it, or isn’t subservient to the user experience, rethink.

And yes, I am going to take this opportunity to link once again to Alex’s article The ���Developer Experience��� Bait-and-Switch. Please read it if you haven’t already. Please re-read it if you have.

Anyway, my main reason for writing this is to point you to thoughtful posts like Hidde’s and Chris’s. I think it’s great to see people thoughtfully weighing up the pros and cons of choosing any particular technology���I’m a bit obsessed with the topic of evaluating technology.

If you’re weighing up the pros and cons of using, say, a particular JavaScript library or framework, that’s wonderful. My worry is that there are people working in front-end development who aren’t putting that level of thought into their technology choices, but are instead using a particular framework because it’s what they’re used to.

To quote Grace Hopper:

The most dangerous phrase in the language is, ���We���ve always done it this way.���

April 18, 2019

Inlining SVG background images in CSS with custom properties

Here’s a tiny lesson that I picked up from Trys that I’d like to share with you…

I was working on some upcoming changes to the Clearleft site recently. One particular component needed some SVG background images. I decided I’d inline the SVGs in the CSS to avoid extra network requests. It’s pretty straightforward:

.myComponent {

background-image: url('data:image/svg xml;utf8, ... ');

}

You can basically paste your SVG in there, although you need to a little bit of URL encoding: I found that converting # to # to was enough for my needs.

But here’s the thing. My component had some variations. One of the variations had multiple background images. There was a second background image in addition to the first. There’s no way in CSS to add an additional background image without writing a whole background-image declaration:

.myComponent--variant {

background-image: url('data:image/svg xml;utf8, ... '), url('data:image/svg xml;utf8, ... ');

}

So now I’ve got the same SVG source inlined in two places. That negates any performance benefits I was getting from inlining in the first place.

That’s where Trys comes in. He shared a nifty technique he uses in this exact situation: put the SVG source into a custom property!

:root {

--firstSVG: url('data:image/svg xml;utf8, ... ');

--secondSVG: url('data:image/svg xml;utf8, ... ');

}

Then you can reference those in your background-image declarations:

.myComponent {

background-image: var(--firstSVG);

}

.myComponent--variant {

background-image: var(--firstSVG), var(--secondSVG);

}

Brilliant! Not only does this remove any duplication of the SVG source, it also makes your CSS nice and readable: no more big blobs of SVG source code in the middle of your style sheet.

You might be wondering what will happen in older browsers that don’t support CSS custom properties (that would be Internet Explorer 11). Those browsers won’t get any background image. Which is fine. It’s a background image. Therefore it’s decoration. If it were an important image, it wouldn’t be in the background.

Progressive enhancement, innit?

April 16, 2019

Three more Patterns Day speakers

There are 73 days to go until Patterns Day. Do you have your ticket yet?

Perhaps you’ve been holding out for some more information on the line-up. Well, I’m more than happy to share the latest news with you���today there are three new speakers on the bill…

Emil Bj��rklund, the technical director at the Malm�� outpost of Swedish agency inUse, is a super-smart person I’ve known for many years. Last year, I saw him on stage in his home town at the Confront conference sharing some of his ideas on design systems. He blew my mind! I told him there and then that he had to come to Brighton and expand on those thoughts some more. This is going to be an unmissable big-picture talk in the style of Paul’s superb talk last year.

Speaking of superb talks from last year, Alla Kholmatova is back! Her closing talk from the first Patterns Day was so fantastic that it I just had to have her come back. Oh, and since then, her brilliant book on Design Systems came out. She’s going to have a lot to share!

The one thing that I felt was missing from the first Patterns Day was a focus on inclusive design. I’m remedying that this time. Heydon Pickering, creator of the Inclusive Components website���and the accompanying book���is speaking at Patterns Day. I’m very excited about this. Given that Heydon has a habit of casually dropping knowledge bombs like the lobotomised owl selector and the flexbox holy albatross, I can’t wait to see what he unleashes on stage in Brighton on June 28th.

Tickets for Patterns Day are still available, but you probably don’t want to leave it ‘till the last minute to get yours. Just sayin’.

The current���still incomplete���line-up comprises:

Una Kravets,

Amy Hupe,

Inayaili de Le��n Persson,

Emil Bj��rklund,

Alla Kholmatova, and

Heydon Pickering.

That isn’t even the full roster of speakers, and it’s already an unmissable event!

I very much hope you’ll join me in the beautiful Duke of York’s cinema on June 28th for a great day of design system nerdery.

April 11, 2019

Design perception

Last week I wrote a post called Dev perception:

I have a suspicion that there���s a silent majority of developers who are working with ���boring��� technologies on ���boring��� products in ���boring��� industries ���you know, healthcare, government, education, and other facets of everyday life that any other industry would value more highly than Uber for dogs.

The sentiment I expressed resonated with a lot of people. Like, a lot of people.

I was talking specifically about web development and technology choices, but I think the broader point applies to other disciplines too.

Last month I had the great pleasure of moderating two panels on design leadership at an event in London (I love moderating panels, and I think I’m pretty darn good at it too). I noticed that the panels comprised representatives from two different kinds of companies.

There were the digital-first companies like Spotify, Deliveroo, and Bulb���companies forged in the fires of start-up culture. Then there were the older companies that had to make the move to digital (transform, if you will). I decided to get a show of hands from the audience to see which kind of company most people were from. The overwhelming majority of attendees were from more old-school companies.

Just as most of the ink spilled in the web development world goes towards the newest frameworks and toolchains, I feel like the majority of coverage in the design world is spent on the latest outputs from digital-first companies like AirBnB, Uber, Slack, etc.

The end result is the same. A typical developer or designer is left feeling that they���and their company���are behind the curve. It’s like they’re only seeing the Instagram version of their industry, all airbrushed and filtered, and they’re comparing that to their day-to-day work. That can’t be healthy.

Personally, I’d love to hear stories from the trenches of more representative, traditional companies. I also think that would help get an important message to people working in similar companies:

You are not alone!

April 10, 2019

Split

When I talk about evaluating technology for front-end development, I like to draw a distinction between two categories of technology.

On the one hand, you’ve got the raw materials of the web: HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. This is what users will ultimately interact with.

On the other hand, you’ve got all the tools and technologies that help you produce the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript: pre-processors, post-processors, transpilers, bundlers, and other build tools.

Personally, I’m much more interested and excited by the materials than I am by the tools. But I think it’s right and proper that other developers are excited by the tools. A good balance of both is probably the healthiest mix.

I’m never sure what to call these two categories. Maybe the materials are the “external” technologies, because they’re what users will interact with. Whereas all the other technologies���that mosty live on a developer’s machine���are the “internal” technologies.

Another nice phrase is something I heard during Chris’s talk at An Event Apart in Seattle, when he quoted Brad, who talked about the front of the front end and the back of the front end.

I’m definitely more of a front-of-the-front-end kind of developer. I have opinions on the quality of the materials that get served up to users; the output should be accessible and performant. But I don’t particularly care about the tools that produced those materials on the back of the front end. Use whatever works for you (or whatever works for your team).

As a user-centred developer, my priority is doing what’s best for end users. That’s not to say I don’t value developer convenience. I do. But I prioritise user needs over developer needs. And in any case, those two needs don’t even come into conflict most of the time. Like I said, from a user’s point of view, it’s irrelevant what text editor or version control system you use.

Now, you could make the argument that anything that is good for developer convenience is automatically good for user experience because faster, more efficient development should result in better output. While that’s true in theory, I highly recommend Alex’s post, The ���Developer Experience��� Bait-and-Switch.

Where it gets interesting is when a technology that’s designed for developer convenience is made out of the very materials being delivered to users. For example, a CSS framework like Bootstrap is made of CSS. That’s different to a tool like Sass which outputs CSS. Whether or not a developer chooses to use Sass is irrelevant to the user���the final output will be CSS either way. But if a developer chooses to use a CSS framework, that decision has a direct impact on the user experience. The user must download the framework in order for the developer to get the benefit.

So whereas Sass sits at the back of the front end���where I don’t care what you use���Bootstrap sits at the front of the front end. For tools like that, I don’t think saying “use whatever works for you” is good enough. It’s got to be weighed against the cost to the user.

Historically, it’s been a similar story with JavaScript libraries. They’re written in JavaScript, and so they’re going to be executed in the browser. If a developer wanted to use jQuery to make their life easier, the user paid the price in downloading the jQuery library.

But I’ve noticed a welcome change with some of the bigger JavaScript frameworks. Whereas the initial messaging around frameworks like React touted the benefits of state management and the virtual DOM, I feel like that’s not as prevalent now. You’re much more likely to hear people���quite rightly���talk about the benefits of modularity and componentisation. If you combine that with the rise of Node���which means that JavaScript is no longer confined to the browser���then these frameworks can move from the front of the front end to the back of the front end.

We’ve certainly seen that at Clearleft. We’ve worked on multiple React projects, but in every case, the output was server-rendered. Developers get the benefit of working with a tool that helps them. Users don’t pay the price.

For me, this question of whether a framework will be used on the client side or the server side is crucial.

Let me tell you about a Clearleft project that sticks in my mind. We were working with a big international client on a product that was going to be rolled out to students and teachers in developing countries. This was right up my alley! We did plenty of research into network conditions and typical device usage. That then informed a tight performance budget. Every design decision���from web fonts to images���was informed by that performance budget. We were producing lean, mean markup, CSS, and JavaScript. But we weren’t the ones implementing the final site. That was being done by the client’s offshore software team, and they insisted on using React. “That’s okay”, I thought. “React can be used server-side so we can still output just what’s needed, right?” Alas, no. These developers did everything client side. When the final site launched, the log-in screen alone required megabytes of JavaScript just to render a form. It was, in my opinion, entirely unfit for purpose. It still pains me when I think about it.

That was a few years ago. I think that these days it has become a lot easier to make the decision to use a framework on the back of the front end. Like I said, that’s certainly been the case on recent Clearleft projects that involved React or Vue.

It surprises me, then, when I see the question of server rendering or client rendering treated almost like an implementation detail. It might be an implementation detail from a developer’s perspective, but it’s a key decision for the user experience. The performance cost of putting your entire tech stack into the browser can be enormous.

Alex Sanders from the development team at The Guardian published a post recently called Revisiting the rendering tier . In it, he describes how they’re moving to React. Now, if this were a move to client-rendered React, that would make a big impact on the user experience. The thing is, I couldn’t tell from the article whether React was going to be used in the browser or on the server. The article talks about “rendering”���which is something that browsers do���and “the DOM”���which is something that only exists in browsers.

So I asked. It turns out that this plan is very much about generating HTML and CSS on the server before sending it to the browser. Excellent!

With that question answered, I’m cool with whatever they choose to use. In this case, they’re choosing to use CSS-in-JS (although, to be pedantic, there’s no C anymore so technically it’s SS-in-JS). As long as the “JS” part is JavaScript on a server, then it makes no difference to the end user, and therefore no difference to me. Not my circus, not my monkeys. For users, the end result is the same whether styling is applied via a selector in an external stylesheet or, for example, via an inline style declaration (and in some situations, a server-rendered CSS-in-JS solution might be better for performance). And so, as a user-centred developer, this is something that I don’t need to care about.

Except…

I have misgivings. But just to be clear, these misgivings have nothing to do with users. My misgivings are entirely to do with another group of people: the people who make websites.

There’s a second-order effect. By making React���or even JavaScript in general���a requirement for styling something on a web page, the barrier to entry is raised.

At least, I think that the barrier to entry is raised. I completely acknowledge that this is a subjective judgement. In fact, the reason why a team might decide to make JavaScript a requirement for participation might well be because they believe it makes it easier for people to participate. Let me explain…

It wasn’t that long ago that devs coming from a Computer Science background were deriding CSS for its simplicity, complaining that “it’s broken” and turning their noses up at it. That rhetoric, thankfully, is waning. Nowadays they’re far more likely to acknowledge that CSS might be simple, but it isn’t easy. Concepts like the cascade and specificity are real head-scratchers, and any prior knowledge from imperative programming languages won’t help you in this declarative world���all your hard-won experience and know-how isn’t fungible. Instead, it seems as though all this cascading and specificity is butchering the modularity of your nicely isolated components.

It’s no surprise that programmers with this kind of background would treat CSS as damage and find ways to route around it. The many flavours of CSS-in-JS are testament to this. From a programmer’s point of view, this solution has made things easier. Best of all, as long as it’s being done on the server, there’s no penalty for end users. But now the price is paid in the diversity of your team. In order to participate, a Computer Science programming mindset is now pretty much a requirement. For someone coming from a more declarative background���with really good HTML and CSS skills���everything suddenly seems needlessly complex. And as Tantek observed:

Complexity reinforces privilege.

The result is a form of gatekeeping. I don’t think it’s intentional. I don’t think it’s malicious. It’s being done with the best of intentions, in pursuit of efficiency and productivity. But these code decisions are reflected in hiring practices that exclude people with different but equally valuable skills and perspectives.

Rachel describes HTML, CSS and our vanishing industry entry points:

If we make it so that you have to understand programming to even start, then we take something open and enabling, and place it back in the hands of those who are already privileged.

I think there’s a comparison here with toxic masculinity. Toxic masculinity is obviously terrible for women, but it’s also really shitty for men in the way it stigmatises any male behaviour that doesn’t fit its worldview. Likewise, if the only people your team is interested in hiring are traditional programmers, then those programmers are going to resent having to spend their time dealing with semantic markup, accessibility, styling, and other disciplines that they never trained in. Heydon correctly identifies this as reluctant gatekeeping:

By assuming the role of the Full Stack Developer (which is, in practice, a computer scientist who also writes HTML and CSS), one takes responsibility for all the code, in spite of its radical variance in syntax and purpose, and becomes the gatekeeper of at least some kinds of code one simply doesn���t care about writing well.

This hurts everyone. It’s bad for your team. It’s even worse for the wider development community.

Last year, I was asked “Is there a fear or professional challenge that keeps you up at night?” I responded:

My greatest fear for the web is that it becomes the domain of an elite priesthood of developers. I firmly believe that, as Tim Berners-Lee put it, ���this is for everyone.��� And I don���t just mean it���s for everyone to use���I believe it���s for everyone to make as well. That���s why I get very worried by anything that raises��the barrier to entry to web design and web development.

I’ve described a number of dichotomies here:

Materials vs. tools,

Front of the front end vs. back of the front end,

User experience vs. developer experience,

Client-side rendering vs. server-side rendering,

Declarative languages vs. imperative languages.

But the split that worries the most is this:

The people who make the web vs. the people who are excluded from making the web.

April 7, 2019

Drag’n’drop revisited

I got a message from a screen-reader user of The Session recently, letting me know of a problem they were having. I love getting any kind of feedback around accessibility, so this was like gold dust to me.

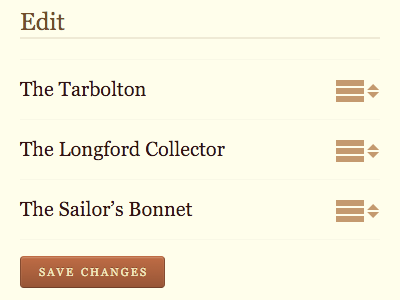

They pointed out that the drag’n’drop interface for rearranging the order of tunes in a set was inaccessible.

Of course! I slapped my forehead. How could I have missed this?

It had been a while since I had implemented that functionality, so before even looking at the existing code, I started to think about how I could improve the situation. Maybe I could capture keystroke events from the arrow keys and announce changes via ARIA values? That sounded a bit heavy-handed though: mess with people’s native keyboard functionality at your peril.

Then I looked at the code. That was when I realised that the fix was going to be much, much easier than I thought.

I documented my process of adding the drag’n’drop functionality back in 2016. Past me had his progressive enhancement hat on:

One of the interfaces needed for this feature was a form to re-order items in a list. So I thought to myself, ���what���s the simplest technology to enable this functionality?��� I came up with a series of select elements within a form.

The problem was in my feature detection:

There���s a little bit of mustard-cutting going on: does the dragula object exist, and does the browser understand querySelector? If so, the select elements are hidden and the drag���n���drop is enabled.

The logic was fine, but the execution was flawed. I was being lazy and hiding the select elements with display: none. That hides them visually, but it also hides them from screen readers. I swapped out that style declaration for one that visually hides the elements, but keeps them accessible and focusable.

It was a very quick fix. I had the odd sensation of wanting to thank Past Me for making things easy for Present Me. But I don’t want to talk about time travel because if we start talking about it then we’re going to be here all day talking about it, making diagrams with straws.

I pushed the fix, told the screen-reader user who originally contacted me, and got a reply back saying that everything was working great now. Success!

April 6, 2019

Cool goal

One evening last month, during An Event Apart Seattle, a bunch of the speakers were gathered in the bar in the hotel lobby, shooting the breeze and having a nightcap before the next day’s activities. In a quasi-philosophical mode, the topic of goals came up. Not the sporting variety, but life and career goals.

As I everyone related (confessed?) their goals, I had to really think hard. I don’t think I have any goals. I find it hard enough to think past the next few months, much less form ideas about what I might want to be doing in a decade. But then I remembered that I did once have a goal.

Back in the ’90s, when I was living in Germany and first starting to make websites, there was a website I would check every day for inspiration: Project Cool’s Cool Site Of The Day. I resolved that my life’s goal was to one day have a website I made be the cool site of the day.

About a year later, to my great shock and surprise, I achieved my goal. An early iteration of Jessica’s site���complete with whizzy DHTML animations���was the featured site of the day on Project Cool. I was overjoyed!

I never bothered to come up with a new goal to supercede that one. Maybe I should’ve just retired there and then���I had peaked.

Megan Sapnar Ankerson wrote an article a few years back about How coolness defined the World Wide Web of the 1990s:

The early web was simply teeming with declarations of cool: Cool Sites of the Day, the Night, the Week, the Year; Cool Surf Spots; Cool Picks; Way Cool Websites; Project Cool Sightings. Coolness awards once besieged the web���s virtual landscape like an overgrown trophy collection.

It’s a terrific piece that ponders the changing nature of the web, and the changing nature of that word: cool.

Perhaps the word will continue to fall out of favour. Tim Berners-Lee may have demonstrated excellent foresight when he added this footnote to his classic document, Cool URIs don’t change���still available at its original URL, of course:

Historical note: At the end of the 20th century when this was written, “cool” was an epithet of approval particularly among young, indicating trendiness, quality, or appropriateness.

April 2, 2019

A walk in the country

Spring sprung last weekend. Saturday was an unseasonably nice and sunny day, so Jessica and I decided to make the most of it with a walk in the countryside.

Our route took us from Woodingdean to Lewes. Woodingdean isn���t too far away from where we live, but the walk there would���ve been beside a busy road so we just took the bus for that portion.

Being on the bus means we didn���t stop to take note of an interesting location. Just outside the Nuffield hospital is the unassuming opening of the Woodingdean Water Well. This is the deepest hand-dug well in the world���deeper than the Empire State Building is tall���dug over the course of four years in the mid nineteenth century. I didn���t even know of its existence until Brian told me about it.

From Woodingdean, we walked along Juggs Road. Originally a Roman ridgeway, it was named for the fishwives travelling from Brighton to Lewes with their marine wares. This route took us over Newmarket Hill, the site of many mock battles in the 18th century, for the amusement of the royals on a day out from the Pavilion.

Walking through Kingston, we came to the Ashcombe Windmill, where I pet a nice horsey.

Then it was on into Lewes, where we could admire the handsome architecture of Lewes Cathedral ���the local wags��� name for Harveys Brewery. Thanks to Ben���s connections, Clearleft managed to get a behind-the-scenes tour of this Victorian marvel a few months ago.

This time round, there would be no brewery tour, but that���s okay���there���s a shop right outside. We chose an appropriate ale to accompany a picnic of pork pie and apple.

Having walked all the way to Lewes, it would���ve been a shame to return empty-handed, so before getting the bus back to Brighton, we popped into Mays Farm Cart and purchased a magnificent forerib of beef straight from the farm.

���Twas a most worthwhile day out.

Dev perception

Chris put together a terrific round-up of posts recently called Simple & Boring. It links off to a number of great articles on the topic of complexity (and simplicity) in web development.

I had linked to quite a few of the articles myself already, but one I hadn’t seen was from David DeSandro who wrote New tech gets chatter:

You don’t hear about TextMate because TextMate is old. What would I tweet? Still using TextMate. Still good.

I think that’s a very good point.

It’s relatively easy to write and speak about new technologies. You’re excited about them, and there’s probably an eager audience who can learn from what you have to say.

It’s trickier to write something insightful about a tried and trusted (perhaps even boring) technology that’s been around for a while. You could maybe write little tips and tricks, but I bet your inner critic would tell you that nobody’s interested in hearing about that old tech. It’s boring.

The result is that what’s being written about is not a reflection of what’s being widely used. And that’s okay …as long as you know that’s the case. But I worry that theres’s a perception problem. Because of the outsize weighting of new and exciting technologies, a typical developer could feel that their skills are out of date and the technologies they’re using are pass�� …even if those technologies are actually in wide use.

I don’t know about you, but I constantly feel like I’m behind the curve because I’m not currently using TypeScript or GraphQL or React. Those are all interesting technologies, to be sure, but the time to pick any of them up is when they solve a specific problem I’m having. Learning a new technology just to mitigate a fear of missing out isn’t a scalable strategy. It’s reasonable to investigate a technology because you genuinely think it’s exciting; it’s quite another matter to feel like you must investigate a technology in order to survive. That way lies burn-out.

I find it very grounding to talk to Drew and Rachel about the people using their Perch CMS product. These are working developers, but they are far removed from the world of tools and frameworks forged in the startup world.

In a recent (excellent) article comparing the performance of Formula One websites, Jake made this observation at the end:

However, none of the teams used any of the big modern frameworks. They’re mostly Wordpress & Drupal, with a lot of jQuery. It makes me feel like I’ve been in a bubble in terms of the technologies that make up the bulk of the web.

I think this is very astute. I also think it’s completely understandable to form ideas about what matters to developers by looking at what’s being discussed on Twitter, what’s being starred on Github, what’s being spoken about at conferences, and what’s being written about on Ev’s blog. But it worries me when I see browser devrel teams focusing their efforts on what appears to be the needs of typical developers based on the amount of ink spilled and breath expelled.

I have a suspicion that there’s a silent majority of developers who are working with “boring” technologies on “boring” products in “boring” industries …you know, healthcare, government, education, and other facets of everyday life that any other industry would value more highly than Uber for dogs.

Trys wrote a great blog post called City life, where he compares his experience of doing CMS-driven agency work with his experience working at a startup in Shoreditch:

I was chatting to one of the team about my previous role. ���I built two websites a month in WordPress���.

They laughed��� ���WordPress! Who uses that anymore?!���

Nearly a third of the web as it turns out - but maybe not on the Silicon Roundabout.

I’m not necessarily suggesting that there should be more articles and talks about older, more established technologies. Conferences in particular are supposed to give audiences a taste of what’s coming���they can be a great way of quickly finding out what’s exciting in the world of development. But we shouldn’t feel bad if those topics don’t match our day-to-day reality.

Ultimately what matters is building something���a website, a web app, whatever���that best serves end users. If that requires a new and exciting technology, that’s great. But if it requires an old and boring technology, that’s also great. What matters here is appropriateness.

When we’re evaluating technologies for appropriateness, I hope that we will do so through the lens of what’s best for users, not what we feel compelled to use based on a gnawing sense of irrelevancy driven by the perceived popularity of newer technologies.

Jeremy Keith's Blog

- Jeremy Keith's profile

- 55 followers