Jeremy Keith's Blog, page 120

November 1, 2013

Wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey stuff

I met up with Remy a few months back to try to help him finalise the line-up for this year’s Full Frontal conference. Remy puts a lot of thought into crafting a really solid line-up. He was in a good position too: the conference was already sold out so he didn’t have to worry about having a big-name speaker to put bums on seats—he could concentrate entirely on finding just the right speaker for the final talk.

He described the kind of “big picture” talk he was looking for, and I started naming some names and giving him some ideas of people to contact.

Imagine my surprise then, when—while we were both in New York for Brooklyn Beta—I received a lengthy email from Remy (pecked out on his phone), saying that he had decided who wanted to do the closing talk at Full Frontal. He wanted me to do it.

Now, this was just a couple of weeks ago so my first thought was “No way! I don’t have enough time to prepare a talk.” It takes me quite a while to prepare a new presentation.

But then he described—in quite some detail—what he wanted me to talk about …and it’s exactly the kind of stuff that I really enjoy geeking out about: long-term thinking, digital preservation, and all that jazz. So I said yes.

That’s why I’ve spent the last couple of weeks quietly freaking out, attempting to marshall my thoughts and squeeze them into Keynote. The title of my talk is Time. Pretentious? Moi?

I’m trying to pack a lot into this presentation. I’ve already had to kill some of my darlings and drop some of the more esoteric stuff, but damn it, it’s hard to still squeeze everything in.

The trouble with researching this @FullFrontalConf talk is that I keep going down rabbit holes of Cherenkov radiation and Harrington events.

— Jeremy Keith (@adactio) October 30, 2013

I’ve been immersed in research and link-making, reading and huffduffing all things time-related. In the course of my hypertravels, I discovered that there’s an entire event devoted to “the origins, evolution, and future of public time.” It’s called Time For Everyone and it’s taking place in California …at exactly the same time as Full Frontal.

Here’s the funny thing: the description for the event is *exactly* the same as the description I gave Remy for my talk:

This thing all things devours:

Birds, beasts, trees, flowers;

Gnaws iron, bites steel;

Grinds hard stones to meal;

Slays king, ruins town,

And beats high mountain down.

If you’re coming along to Full Frontal next Friday, I hope you’ll be in a receptive mood. I also hope that Remy won’t mind that what I’m going to present isn’t exactly what he asked for …but I think it’s interesting stuff.

I just wish I had more time.

Tagged with

fullfrontal

conference

time

presentation

preparation

research

speaking

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

October 26, 2013

Medieval times

I just got back from Nürnberg where I gave the closing talk at the cheap’n’cheerful border:none event. It was my first time in Nürnberg and I wish I could’ve stayed longer in such a beautiful place. I would’ve liked to stick around for today’s Open Device Lab admin meetup, but alas I had to get up at the crack of dawn to start making my way back to Brighton.

I was in Germany last month too. That time I was in Freiburg, where I was giving the closing talk at Smashing Conference. That was a lot of fun:

So I threw away my slidedeck and went Keynote commando.

The video from that slideless talk is up on Vimeo now for your viewing and/or downloading pleasure.

If you watch it through to the end, then you’ll know why I could be found immediately afterwards showing people some centuries-old carvings on Freiburg’s cathedral.

Tagged with

bordernone

bono13

conference

nurnberg

freiburg

smashingconf

speaking

history

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

October 21, 2013

Classy values

Two articles were published today that take diametrically opposed viewpoints on how developers should be using CSS:

Thierry Koblentz writes about Challenging CSS Best Practices for Smashing Magazine.

Ben Darlow writes about Cargo Cult CSS on his own site.

I don’t want to attempt to summarise either article as they both give fairly lengthy in-depth explanations of their positions, although I find that they’re both a bit extreme. They’re both ostensibly about CSS, though in reality they’re more about the class values we add to our HTML (and remember, as Ben points out, class is an HTML attribute; there’s no such thing as CSS classes).

Thierry advocates entirely presentational values, like this:

Meanwhile Ben argues that this makes the markup less readable and maintainable, and that we should strive to have human-readable markup, more like the example that Thierry dismisses as inefficient:

Here’s my take on it: this isn’t an either/or situation. I think that both extremes are problematic. If you make your class values entirely presentational in order to make your CSS more modular, you’re offloading a maintainability expense onto your markup. But if you stick to strictly semantically-meaningful class values, your CSS is probably going to be a lot harder to write in a modular, maintainable way.

Fortunately, the class attribute takes a space-separated list of values. That means you can have your OOCSS/SMACSS/BEM cake and semantically eat it too:

The “media” value describes the content, which is traditionally what a semantically-meaningful class name is supposed to do. Meanwhile, the “Bfc” and “M-10” values say nothing about the nature of the content, but everything about how it should be displayed.

Is it wasteful to use a class value that is never used by the CSS? Possibly. But I think it serves a useful purpose for any humans (developer or end user) reading the markup, or potentially machines parsing/scraping the markup.

I’ve used class values that never get touched by CSS. Here on adactio.com, if I want to mark up something as being a scare quote, I’ll write:

scare quote

But nowhere in my CSS do I use a selector like this:

q.scare { }

Speaking of scare quotes….

Both of the aforementioned articles begin by establishing that their approach is the minority viewpoint and that web developers everywhere are being encouraged to adapt the other way of working.

Ben writes:

Most disconcertingly, these methodologies have seen widespread adoption thanks to prominent bloggers evangelising their usage as ‘best practice’.

Meanwhile Thierry writes:

But when it comes to the presentational layer, “best practice” goes way beyond the separation of resources.

Perhaps both authors have more in common than they realise: they certainly seem to agree that any methodology you don’t agree with should be labelled as a best practice and wrapped in scare quotes.

Frankly, I think this attitude does more harm than good. A robust argument should stand on its own strengths—it shouldn’t rely on knocking down straw men that supposedly represent the opposing viewpoint.

Some of the trigger words that grind my gears are: dogma, zealot, purist, sacred, and pedant. I’ve mentioned this before:

Whenever someone labels those they disagree with as “dogmatic” or “purist”, it’s a lazy meaningless barb (like calling someone a hipster). “I’m passionate; you’re dogmatic. I sweat the details; you’re a purist.” Even when I agree completely with the argument being made—as was the case withAndy’s superb talk at South by Southwest this year—I cringe to hear the “dogma” attack employed: especially when the argument is strong enough to stand up on its own without resorting to Croftian epithets.

That’s what I was getting at when I tried to crack this joke on Twitter:

@drewm When a designer is picky, it’s called sweating the details. When a developer is picky, it’s called being pedantic.

— Jeremy Keith (@adactio) September 10, 2013

…but all I ended up doing was making a cheap shot about designers (and developers for that matter), which wasn’t my intention. The point I was intending to make was that we all throw a lot of stones from our glasses houses.

So if you’re going to write an article about the right way to do something, don’t start by labelling dissenting schools of thought as dogmatic or purist.

Physician, heal thyself.

Tagged with

css

semantic

markup

standards

development

html

class

maintainability

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

October 16, 2013

America

I’ve just come back from a multi-hop trip to the States, spanning three cities in just over two weeks.

It started with an all-too-brief trip to San Francisco for Science Hack Day, which—as I’ve already described—was excellent. It was a shame that it was such a flying visit and I didn’t get to see many people. But then again, I’ll be back in December for An Event Apart San Francisco.

It was An Event Apart that took me to my second destination: Austin, Texas. The conference was great, as always. But was really nice was having some time afterwards to explore the town. Being in Austin when it’s not South by Southwest is an enjoyable experience that I can heartily recommend.

Christopher and Ari took me out to Lockhart to experience Smitty’s barbecue—a place with a convoluted family drama and really, really excellent smoked meat. I never really “got” Texas BBQ until now. I always thought I liked the sauced-based variety, but now I understand: if the BBQ is good enough, you don’t need the sauce.

For the rest of my stay, Sam was an excellent host, showing me around her town until it was time for me to take off for New York city.

To start with, I was in Manhattan. I was going to be speaking at Future Of Web Design right downtown on 42nd street, and I showed up a few days early to rendezvous with Jessica and do some touristing.

We perfected the cheapskate’s guide to Manhattan, exploring the New York Public Library, having Tiff show us around the New York Times, and wrangling a tour of the MoMA from Ben Fino-Radin, who’s doing some fascinating work with the digital collection.

I gave my FOWD talk, which went fine once the technical glitches were sorted out (I went through three microphones in five minutes). The conference was in a cinema, which meant my slides were giganormous. That was nice, but the event had an odd kind of vibe. Maybe it was the venue, or maybe it was the two-track format …I really don’t like two-track conferences; I constantly feel like I’m missing out on something.

I skipped out on the second day of the conference to make my way over the bridge to Brooklyn in time for my third trip to Brooklyn Beta.

This year, they tried something quite different. For the first two days, there was a regular Brooklyn Beta: 300 lovely people gathered together at the Invisible Dog, ostensibly to listen to talks but in reality to hang out and chat. It was joyous.

Then on the third and final day, those 300 people decamped to Brooklyn’s Navy Yard to join a further 1000 people. There we heard more talks and had more chats.

Alas, the acoustics in the hangar-like space battled against the speakers. That’s why I made sure to grab a seat near the front for the afternoon talks. I found myself with a front-row seat for a series of startup stories and app tales. Then, without warning, the tech talks were replaced with stand-up comics. The comedians were very, very good (Reggie Watts!) …but I found it hard to pay attention because I realised I was in a living nightmare: somehow I was in the front-row seat of a stand-up comedy show. I spent the entire time thinking “Please don’t pick on me, please don’t pick on me, please don’t…” I couldn’t sneak out either, because that would’ve only drawn attention to myself.

But apart from confronting me with my worst fears, Brooklyn Beta was great …I’m just not sure it scales well from 300 to 1300.

And with that, my American sojourn came to an end. I’m glad that the stars aligned in such a way that I was able to hit up four events in my 16 day trip:

Science Hack Day San Francisco,

An Event Apart Austin,

Future Of Web Design New York, and

Brooklyn Beta 2013.

Tagged with

america

conference

travel

aea

aneventapart

sciencehackday

scihack

austin

sanfrancisco

newyork

fowd

brooklynbeta

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

October 15, 2013

Jocelyn Bell Burnell

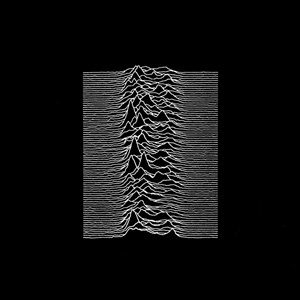

When most people see Peter Saville’s iconic cover for Unknown Pleasures, they think of Joy Division and the tragically early death of lead singer Ian Curtis. But whenever I come across variations of FACT 10, I see a tribute to Jocelyn Bell Burnell.

The album’s artwork is an inverted version of an illustration from the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Astronomy (which brings up all sorts of fascinating questions about Saville’s “remixing” of the original). It represents a series of pulses from CP 1919, the first pulsar ever discovered.

The regularity of the radio pulses is what caused the source to be initially labelled LGM-1, standing for “Little Green Men.” But the actual cause of the speed and regularity turned out to be equally stunning: a magnetised incredibly massive neutron star rotating once every 1.3373 seconds.

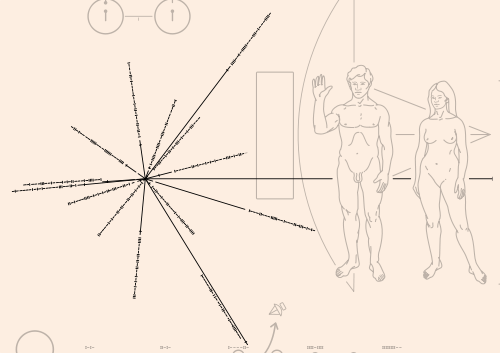

Pulsars keep their regularity for millions of years. They are the lighthouses of their host galaxies. When Carl Sagan was designing the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager golden record, he included a pulsar map that pointed the way to Earth—a decision that was criticised by many for inviting potentially hostile attention.

That first pulsar— CP 1919 (or LGM-1)—was discovered by Jocelyn Bell Burnell on November 28, 1967 while she was still a PH.d student, using the radio telescope she helped build. In fact, she discovered the first four pulsars. In 1974, the Nobel Prize in physics was, for the first time, awarded to an astronomer. It went to her Professor, Antony Hewish.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell herself claims no animosity on this point, but I can’t help but wonder if the committee might have made a different decision had the discoverer of one of the most important astronomical finds of the twentieth century had been a man.

She describes how the Daily Mail ran the pulsar discovery story with the headline Girl Discovers Little Green Men:

They did not know what to do with a young female scientist, you were a young female, you were page three, you weren’t a scientist.

For a fascinating insight into the career of Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell, I highly recommend listening to Jim al-Khalili’s interview with her on BBC 4’s The Life Scientific.

The Life Scientific: Jocelyn Bell-Burnell on Huffduffer

Tagged with

science

astronomy

pulsar

sexism

findingada

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

October 14, 2013

Listen to dConstruct 2013

If you didn’t make it to this year’s dConstruct, at least your ears can catch up. If you did make it to this year’s dConstruct, your ears can experience the fun all over again.

The audio is available, is what I’m saying here.

Amber Case: Ambient Location and the Future of the Interface

Luke Wroblewski: Infinite Inputs

Nicole Sullivan: Don’t Feed the Trolls

Simone Rebaudengo: Great; things are connected, but what will they actually talk about?

Sarah Angliss: Tech and the Uncanny

Keren Elazari: The Heroes and Anti-heroes of the Information Age

Maciej Cegłowski: Fan is a Tool-Using Animal

Dan Williams: Unexpected Item In The Bagging Area

Adam Buxton: Is My Laptop Ruining My Life?

The audio is on Huffduffer for your listening pleasure. If you’d like to take it with you on the go, here’s the RSS feed—just pop that into your podcasting/catching software of choice.

While you’re at it, this might be a nice opportunity to go back and explore the dConstruct archive where you can find every talk from every dConstruct from 2005 to 2013. That’s 70 talks, or about 46 hours of listening pleasure.

Share and enjoy!

Tagged with

dconstruct

dconstruct2013

conference

audio

presentation

huffduffer

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

October 4, 2013

Radio Free Earth

Back at the first San Francisco Science Hack Day I wanted to do some kind of mashup involving the speed of light and the distance of stars:

I wanted to build a visualisation based on Matt’s brilliant light cone idea, but I found it far too daunting to try to find data in a usable format and come up with a way of drawing a customisable geocentric starmap of our corner of the galaxy. So I put that idea on the back burner…

At this year’s San Francisco Science Hack Day, I came back to that idea. I wanted some kind of mashup that demonstrated the connection between the time that light has travelled from distant stars, and the events that would have been happening on this planet at that moment. So, for example, a star would be labelled with “the battle of Hastings” or “the sack of Rome” or “Columbus’s voyage to America”. To do that, I’d need two datasets; the distance of stars, and the dates of historical events (leaving aside any Gregorian/Julian fuzziness).

For wont of a better hack, Chloe agreed to help me out. We set to work finding a good dataset of stellar objects. It turned out that a lot of the best datasets from NASA were either about our local solar neighbourhood, or else really distant galaxies and stars that are emitting prehistoric light.

The best dataset we could find was the Near Star Catalogue from Uranometria but the most distant star in that collection was only 70 or 80 light years away. That meant that we could only mash it up with historical events from the twentieth century. We figured we could maybe choose important scientific dates from the past 70 or 80 years, but to be honest, we really weren’t feeling it.

We had reached this impasse when it was time for the Science Hack Day planetarium show. It was terrific: we were treated to a panoramic tour of space, beginning with low Earth orbit and expanding all the way out to the cosmic microwave background radiation. At one point, the presenter outlined the reach of Earth’s radiosphere. That’s the distance that ionosphere-penetrating radio and television signals from Earth, travelling at the speed of light, have reached. “It extends about 70 light years out”, said the presenter.

This was perfect! That was exactly the dataset of stars that we had. It was a time for a pivot. Instead of the lofty goal of mapping historical events to the night sky, what if we tried to do something more trivial and fun? We could demonstrate how far classic television shows have travelled. Has Star Trek reached Altair? Is Sirius receiving I Love Lucy yet?

No, not TV shows …music! Now we were onto something. We would show how far the songs of planet Earth had travelled through space and which stars were currently receiving which hits.

Chloe remembered there being an API from Billboard, who have collected data on chart-topping songs since the 1940s. But that API appears to be gone, and the Echonest API doesn’t have chart dates. So instead, Chloe set to work screen-scraping Wikipedia for number one hits of the 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s …you get the picture. It was a lot of finding and replacing, but in the end we had a JSON file with every number one for the past 70 years.

Meanwhile, I was putting together the logic. Our list of stars had the distances in parsecs. So I needed to convert the date of a number one hit song into the number of parsecs that song had travelled, and then find the last star that it has passed.

We were tempted—for developer convenience—to just write all the logic in JavaScript, especially as our data was in JSON. But even though it was just a hack, I couldn’t bring myself to write something that relied on JavaScript to render the content. So I wrote some really crappy PHP instead.

By the end of the first day, the functionality was in place: you could enter a date, and find out what was number one on that date, and which star is just now receiving that song.

After the sleepover (more like a wakeover) in the aquarium, we started to style the interface. I say “we” …Chloe wrote the CSS while I made unhelpful remarks.

For the icing on the cake, Chloe used her previous experience with the Rdio API to add playback of short snippets of each song (when it’s available).

Here’s the (more or less) finished hack:

Basically, it’s a simple mashup of music and space …which is why I spent the whole time thinking “What would Matt do?”

Just keeping hitting that button to hear a hit from planet Earth and see which lucky star is currently receiving the signal.*

Science!

*I know, I know: the inverse-square law means it’s practically impossible that the signal would be in any state to be received, but hey, it’s a hack.

Tagged with

radio-free-earth

space

music

science

scihack

sciencehackday

hackday

hacking

hack

mashup

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

October 2, 2013

Science Hack Day San Francisco

When I organised the first ever Science Hack Day in London in 2010, I made sure to write about how I organised the event. That’s because I wanted to encourage other people to organise their own Science Hack Days:

If I can do it, anyone can. And anyone should.

Later that year, Ariel organised a Science Hack Day in Palo Alto at the Institute For The Future. It was magnificent. Since then, Ariel has become a tireless champion and global instigator of Science Hack Day, spreading the idea, encouraging new events all over the world, and where possible, travelling to them. I just got the ball rolling—she has really run with it.

She organised another Science Hack Day in San Francisco for last weekend and I was lucky enough to attend—it coincided nicely with my travel plans to the States for An Event Apart in Austin. Once again, it was absolutely brilliant. There were tons of ingenious hacks, and the attendees were a wonderfully diverse bunch: some developers and designers, but also plenty of scientists and students, many (perhaps most) from out of town.

But best of all was the venue: The California Academy of Sciences. It’s a fantastic museum, and after 5pm—when the public left—we had the place to ourselves. Penguins, crocodiles, a rainforest, an aquarium …it’s got it all. I didn’t get a chance to do all of the activities that were provided—I was too busy hacking or helping out—like stargazing on the roof, or getting a tour of the archives. But I did make it to the private planetarium show, which was wonderful.

The Science Hackers spent the night, unrolling their sleeping bags in all the nooks and crannies of the acquarium and the African hall. It was like being a big kid. Mind you, the fun of sleeping over in such a great venue was somewhat tempered by the fact that trying to sleep in a sleeping bag on just a yoga mat on a hard floor is pretty uncomfortable. I was quite exhausted by day two of the event, but I powered through on the wave of infectous enthusiasm exhibited by all the attendees.

Then when it came time to demo all the hacks …well, I was blown away. So much cool stuff.

Ariel and her team really outdid themselves. I’m so happy I was able to make it to the event. If you get the chance to attend a Science Hack Day, take it. And if there isn’t one happening near you, why not organise one? Ariel has put together a handy checklist to get you started so you can get excited and make things with science.

I’m still quite amazed that this was the 24th Science Hack Day! When I organised the first one three years ago, I had no idea that it could spread so far, but thanks to Ariel, it has become a truly special phenomenon.

Tagged with

sciencehackday

scihack

science

sanfrancisco

hacking

event

hacks

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

September 24, 2013

The ghost of browsers past

Even before a line of code was written for the line-mode browser simulator when we gathered together at CERN, there was a gleeful period of digital spelunking.

We poked at the markup of the first ever website…

What’s that NEXTID element? Turns it out it’s something specific to the NeXT operating system.

Why does the first iteration of HTML already contain H1 through to H6? It’s because they were lifted wholesale from a flavour of SGML—Standard Generalized Markup Language—that was already in use at CERN.

Oh, and Brian asked Robert Cailliau why they went with the term World Wide Web. “Well,” he said, “we had to call it something. And we thought we could always change it later.”

Then there was the story of the line-mode browser. It was created by Nicola Pellow, who was a student at CERN in 1990. She later worked on the Mac browser but her involvement with kickstarting the world wide web ended around 1993. She never showed up to any of the reunions.

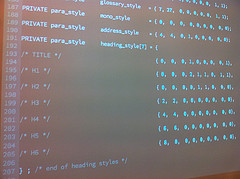

We poked around in the (surprisingly short) source code of the line-mode browser. We found the lines that described how elements should be styled—the term “style sheet” appeared in a comment!

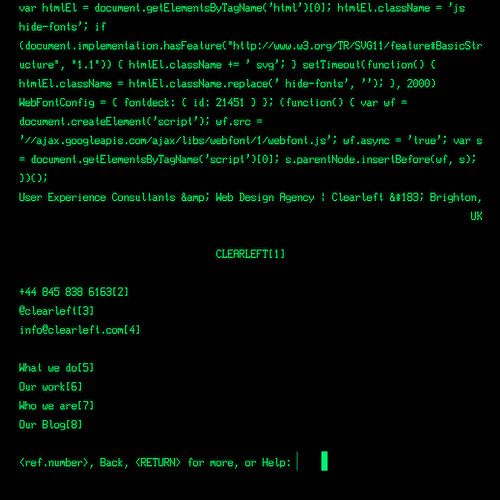

If you’ve fired up the line-mode browser simulator and run some websites through it, you’ll probably see occasions where a whole bunch of JavaScript—nestled between script tags in the head of the document—gets rendered to the screen.

We could’ve hidden that JavaScript, but we made a deliberate decision to display it. That’s what the line-mode browser would have done. The script element didn’t exist back then. Heck, JavaScript didn’t exist back then. So browsers would have handled the unknown element in the standard HTML way: ignore the opening and closing tags and just render what’s in-between them. That’s still the error-handling model for unrecognised elements in HTML.

This is why we used to write our JavaScript like this:

The HTML comments stopped the JavaScript from being rendered to the screen in older browsers (like the line-mode browser). Using the opening HTML comment comment with a //.

I remember doing this when I first started making websites in the 90s. You can see it if you view source on the first version of this website.

Later on, we all switched to XHTML so we updated the syntax to make it valid XML.

The <!--[[CDATA</code> part stops an XML parser from trying to parse the JavaScript. But HTML parsers would chould on that because it starts with an angle bracket. Hence the JavaScript-style <code>//</code> comment.</p>

<p>Anyway, we don’t bother with HTML or XHTML comments at the start of our script blocks anymore. And <em>that’s</em> why the line-mode browser simulator renders the JavaScript to the screen.</p>

<p>Note that the JavaScript isn’t executed. That’s thanks to a clever little hack by Remy: the line-mode browser simulator changes the <code>type</code> attribute of every <code>script</code> element to <code>text/plain</code>, effectively defusing them. Smart!</p>

<hr />

<p>

Tagged with

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/brows...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/stand...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/web&q...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/histo...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/cern&...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/devda...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/parsi...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/hacki...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/html&...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/marku...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/scrip...

<a rel="tag" href="http://adactio.com/journal/tags/javas...

</p>

<hr />

<form method="post" action="http://adactio.com/webmention.php&quo...

<p>Have you published a response to this? <label for="webmention-source">Let me know the <abbr title="Uniform Resource Locator">URL</abbr></label>:</p>

<input type="url" name="source" id="webmention-source" />

<input type="hidden" name="target" value="http://adactio.com/journal/6512/" />

<input type="submit" value="Ping!" />

</form>

The literary operator

One of the great pleasures of putting on Brighton SF right before last year’s dConstruct was how it allowed me to mash up two of my favourite worlds: the web and science fiction (although I don’t believe they’re that far removed from one another). One day I’m interviewing Jeff Noon about his latest book; the next, I’m introducing Tom Armitage on stage at the Brighton Dome.

Those two have since been collaborating on a new project.

You may have seen Jeff’s microspores—a collection of tweet-sized texts, each one an individual seed for a sci-fi story. Here’s Spore #50:

After the Babel Towers attack, lo-fi operators worked the edges of the language, forging new phrases from the fragments of literature. They filled boxes with word shards in the hope of recreating lost stories.

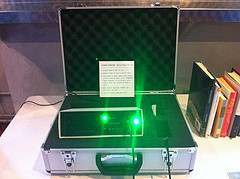

Tom has taken that as the starting point for creating a machine called the literary operator

It’s quite beautiful. It fits inside a suitcase. It has an LED interface. It has a puck that nestles into the palm of your hand. It comes with a collection of books. You take the puck in your hand, pass it over the spine of one of the books, and wait for the LEDs to change. Then you will receive a snippet of reconstructed text, generated Markov-style from the book.

It is an object that is both entirely fictional, and entirely real. Not “design fiction”; just fiction.

You can use/play with the literary operator—and hear from Tom and Jeff—this Thursday evening, September 26th at the Brighton Museum as part of Digital Late. Sarah and Chris are also on the bill so don’t miss it: tickets are a fiver if you book ahead of time.

Tagged with

literaryoperator

hardware

sci-fi

sciencefiction

design

fiction

bdf

brightonsf

dconstruct

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

Jeremy Keith's Blog

- Jeremy Keith's profile

- 55 followers