Jeremy Keith's Blog, page 118

February 4, 2014

Spirit

The first time I went to South by Southwest in 2005 it was an amazing experience (this was before it grew so massively large that its gravity well sucked in all the social media marketing biz dudes in the universe):

I’ve never met so many wonderful people gathered together in one place. It was tribal in the true sense of the word (that would be the cool, fun-loving sense as opposed to the hippy-dippy sense).

There was a great sense of openness and sharing. In a way, it was like the web made flesh—a terrific community of enthusiastic people eager and willing to share their knowledge and experience.

Towards the end of the week, there was the annual web awards show. Everything else about South by Southwest had been so great, I figured I’d go along to that too. Also, someone I know had been nominated for an award.

It was like stepping into opposite-web. The mood switched from one of sharing and openness to one of basically not giving a shit. Everyone in the room was there because either they or someone they knew had been nominated for an award, and that’s all they cared about. Everything before and after that point in the awards ceremony was irrelevant.

In retrospect, I should have seen it coming. If the point of the web and community gatherings—like the SxSW of yore—is for individuals to be subsumed into a larger group that is greater than the sum of its parts, then the whole point of an awards ceremony is to do the exact opposite: to single out some individuals in the group.

I made the mistake of going back to the Southby awards ceremony a year or two later, simply because Ze Frank was presenting it. “How bad could it be?” I thought. But even the inimitable Ze couldn’t save the day.

Every so often, some smart, talented web designers will bemoan the lack of recognition afforded to their craft, industry, work. They wish for the same level of respect that architects or film-makers get, or for the iconic status given to the best of the advertising world’s output in decades past.

Be careful what you wish for, I say. Not only are these the same industries that are rife with horrible business practices like spec work, they are notoriously unfair when it comes to praising individual achievement over the efforts of the group. Worst of all, the proliferation of high-profile awards leads to the practice of producing “award-winning work” i.e. work designed purely to win awards.

I’ve spoken before about the spirit of the web; how I believe certain design principles have influenced the creation and growth of the web. I see that same spirit imbued in online communities and tools like Github. I don’t see that same spirit in the awarding of prizes.

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

February 3, 2014

rel="source"

Aral and his trusty sidekick Victor have taken up residency for a while at the Clearleft office in Middle Street while they work on their very exciting project. It’s nice having them around.

I got chatting to Aral about a markup pattern that’s become fairly prevalent since the rise of Github: linking to the source code for a website or project. You know, like when you see “fork me on Github” links.

We were talking about how it would be nice to have some machine-readable way of explicitly marking up those kind of links, whether they’re in the head of the document, or visible in the body. Sounds like a job for the rel attribute, I thought.

The rel attribute describes the relationship of the current document to the linked document. You can use it on the link element (in the head of your document) and the a element (in the body). The example that everyone is familiar with is rel=”stylesheet” when linking off to a CSS file—the linked document has the relationship of being a stylesheet for the current document.

The rel attribute could theoretically take a space-separated list of any values, just like the class attribute. In practice, there’s much more value in having everyone agree on which rel values should be used.

There used to be a page on the WHATWG site for listing rel values, but it tended to stagnate. So now the official registry for rel values is on the microformats wiki. That’s where you can see which values are recommended for use today and you can also brainstorm new ideas.

The benefit of having one centralised for this is that you can see if someone else has had the same idea as you. Then you can come to agreement on which value to use, so that everyone’s using the same vocabulary instead of just making stuff up.

It doesn’t look like there’s an existing value for the use case of linking to a document’s (or a project’s) source code so I’ve proposed rel=”source”.

Now I should document some use cases of people linking their site to its source code. It might be that wikis qualify as another use case: every “edit” button points to the source of the document in wiki markup.

If you have any thoughts on this pattern, or examples to add, please feel free to add them.

Tagged with

markup

html

rel

source

microformats

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

January 31, 2014

The complexity of HTML

Baldur Bjarnason has written down his thoughts on why he thinks HTML is too complex.

Now we’re back to seeing almost the same level of complexity and messiness in most web pages as we saw in the worst days of table-hacking. The semantic elements from HTML5 are largely unused.

The reason for this, as outlined in an old email by Matthew Thomas, is down to the lack of any visible benefit from browsers:

unless there is an immediate visual or behavioural benefit to using an element, most people will ignore it.

That’s a fair point, but I think it works in the opposite direction too. I’ve seen plenty of designers and developers who are reluctant to use HTML elements because of the default browser styling. The legend element is one example. A more recent one is input type=”date”—until there’s a way for authors to have more say about the generated interface, there’s going to be resistance to its usage.

Anyway, Baldur’s complaint is that HTML is increasing in complexity by adding new elements—section, article, etc.—that provide theoretical semantic value, without providing immediate visible benefits. It’s much the same argument that informed Cory Doctorow’s Metacrap essay over a decade ago. It’s a strong argument.

There’s always a bit of a chick-and-egg situation with any kind of language extension designed to provide data structure: why should authors use the new extensions if there’s no benefit? …and why should parsers (like search engines or browsers) bother doing anything with the new extensions if nobody’s using them?

Whether it’s microformats or new HTML structural elements, the vicious circle remains the same. The solution is to try to make the barrier to entry as low as possible for authors—the parsers/spiders/browsers will follow.

I have to say, I share some of Baldur’s concern. I’ve talked before about the confusion between section and article. Providing two new elements might seem better than providing just one, but in fact it just muddies the waters and confuses authors (in my experience).

But I realise that in the grand scheme of things, I’m nitpicking. I think HTML is in pretty good shape. Baldur said “simply put, HTML is a mess,” and he’s not wrong …but HTML has always been a mess. It’s the worst mess except for all the others that have been tried. When it comes to markup, I think that “perfect” is very much the enemy of “good” (just look at XHTML2).

When I was in San Francisco back in August, I had a good ol’ chat with Tantek about markup complexity. It started when he asked me what I thought of hgroup.

I actually found quite a few use cases for hgroup in my own work …but I could certainly see why it was a dodgy solution. The way that a wrapping hgroup could change the semantic value of an h2, or h3, or whatever …that’s pretty weird, right?

And then Tantek pointed out that there are a number of HTML elements that depend on their wrapper for meaning …and that’s a level of complexity that doesn’t sit well with HTML.

For example, a p is always a paragraph, and em is always emphasis …but li is only a list item if it’s wrapped in ul or ol, and tr is only a table row if it’s wrapped in a table.

(Interestingly, these are the very same elements that browsers will automatically adjust the DOM for—generating ul and table if the author doesn’t include it. It’s like the complexity is damage that the browsers have to route around.)

I had never thought of that before, but the idea has really stuck with me. Now it smells bad to me that it isn’t valid to have a figcaption unless it’s within a figure.

These context-dependent elements increase the learning curve of HTML, and that, in my own opinion, is not a good thing. I like to think that HTML should be easy to learn—and that the web would not have been a success if its lingua franca hadn’t been grokabble by mere mortals.

Tantek half-joked about writing HTML: The Good Parts. The more I think about it, the more I think it’s a pretty good idea. If nothing else, it could make us more sensitive to any proposed extensions to HTML that would increase its complexity without a corresponding increase in value.

Tagged with

markup

html

standards

semantics

extensibility

complexity

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

Communication for America

Mandy has written a great article about making remote teams work. It’s an oft-neglected aspect of working on a product when you’ve got people distributed geographically.

But remote communication isn’t just something that’s important for startups and product companies—it’s equally important for agencies when it comes to client communication.

At Clearleft, we occasionally work with clients right here in Brighton, but that’s the exception. More often than not, the clients are based in London, or somewhere else in the UK. In the case of Code for America, they’re based in San Francisco—that’s eight or nine timezones away (depending on the time of year).

As it turned out, it wasn’t a problem at all. In fact, it worked out nicely. At the end of every day, we had a quick conference call, with two or three people at our end, and two or three people at their end. For us, it was the end of the day: 5:30pm. For them, the day was just starting: 9:30am.

We’d go through what we had been doing during that day, ask any questions that had cropped up over the course of the day, and let them know if there was anything we needed from them. If there was anything we needed from them, they had the whole day to put it together while we went home. The next morning (from our perspective), it would be waiting in our in/drop-boxes.

Meanwhile, from the perspective of Code for America, they were coming into the office every morning and starting the day with a look over our work, as though we had beavering away throughout the night.

Now, it would be easy for me to extrapolate from this that this way of working is great and everyone should do it. But actually, the whole timezone difference was a red herring. The real reason why the communication worked so well throughout the project was because of the people involved.

Right from the start, it was clear that because of time and budget constraints that we’d have to move fast. We wouldn’t have the luxury of debating everything in detail and getting every decision signed off. Instead we had a sort of “rough consensus and running code” approach that worked really well. It worked because everyone understood that was what was happening—if just one person was expecting a more formalised structure, I’m sure it wouldn’t have gone quite so smoothly.

So we provided materials in whatever level of fidelity made sense for the idea under discussion. Sometimes that was a quick sketch. Sometimes it was a fairly high-fidelity mockup. Sometimes it was a module of markup and CSS. Whatever it took.

Most of all, there was a great feeling of trust on both sides of the equation. It was clear right from the start that the people at Code for America were super-smart and weren’t going to make any outlandish or unreasonable requests of Clearleft. Instead they gave us just the right amount of guidance and constraints, while trusting us to make good decisions.

At one point, Jon was almost complaining about not getting pushback on his designs. A nice complaint to have.

Because of the daily transatlantic “stand up” via teleconference, there was a great feeling of inevitability to the project as it came together from idea to execution. Inevitability doesn’t sound like a very sexy attribute of a web project, but it’s far preferable to the kind of project that involves milestones of “big reveals”—the Mad Men approach to project management.

Oh, and we made sure that we kept those transatlantic calls nice and short. They never lasted longer than 10 or 15 minutes. We wanted to avoid the many pitfalls of conference calls.

Tagged with

codeforamerica

clearleft

client

project

process

communication

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

January 27, 2014

Pattern sharing

Mike has written about the Code for America alpha website that we collaborated on:

We chose to work with ClearLeft because they develop a pattern portfolio (a pattern/style library) which would allow us to scale our work to our Brigades. This unique approach has aligned perfectly with our work style and decentralized organizational structure.

Thankfully, I think the approach of delivering a pattern portfolio (instead of just pages) isn’t so unique these days. Mind you, it still seems to be more common with in-house teams than agencies. The Mailchimp pattern library is a classic example.

But agencies like Paravel are—like Clearleft—delivering systems, not pages. Dave wrote about providing responsive deliverables:

Responsive deliverables should look a lot like fully-functioning Twitter Bootstrap-style systems custom tailored for your clients’ needs.

I think that’s a good way of looking at it: a Bootstrap for every project.

Here’s the front-end style guide for Code for America.

Usually these front-end deliverables will be password-protected on the Clearleft extranet for the client’s eyes only, but Code for America are all about openness, so they’re more than willing to let us share it with the world. That makes me very happy. I remember encouraging the guys at Starbucks to publish their front-end style guide and I’ve written about this spirit of sharing before:

These style guides and pattern libraries aren’t being published in an attempt to provide ready-made solutions—every project should have its own distinct pattern library. Instead, these pattern libraries are being published in a spirit of openness and sharing …a way of saying “Hey, this is what worked for us in these particular circumstances.”

If you’re poking around the Code for America style guide, you’ll notice that it borrows some ideas from the pattern primer idea I published a while back. But in this iteration, the markup is available via a toggle—a nice variation. There’s also a patchwork page that provides a nice glance-able uninterrupted view of the same patterns.

Every project is a learning experience and each front-end style guide gives us ideas about how to do the next one better. In fact, Mark is busy working on better internal tools for creating these kinds of deliverables—something we’ll definitely be sharing. In the meantime, I’ll be encouraging other clients to be as open as Code for America have been in allowing us to share these deliverables.

For more on the usefulness of front-end style guides, be sure to read Paul’s article on style guides for the web, Anna’s classic 24 Ways article, and of course, Anna’s pocket guide from Five Simple Steps.

Tagged with

clearleft

frontend

deliverables

process

styleguide

patterns

portfolio

primer

codeforamerica

development

html

markup

css

responsive

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

January 17, 2014

Coding for America

Back when I was wandering around America in August, I mentioned that I met up with Mike Migurski in San Francisco:

I played truant from UX Week this morning to meet up with Mike for a coffee and a chat at Cafe Vega. We were turfed out when the bearded, baseball-capped, Draplinesque barista announced he had to shut the doors because he needed to “run out for some milk.” So we went around the corner to the Code For America office.

It wasn’t just a social visit. Mike wanted to chat about the possibility of working with Clearleft. The Code for America site was being overhauled. The new site needed to communicate directly with volunteers, rather than simply being a description of what Code for America does. But the site also needed to be able to change and adapt as the organisation’s activities expanded. So what they needed was not a set of page designs; they needed a system of modular components that could be assembled in a variety of ways.

This was music to my ears. This sort of systems-thinking is exactly the kind of work that Clearleft likes to get its teeth into. I showed Mike some of the previous work we had done in creating pattern libraries, and it became pretty clear that this was just what they were looking for.

When I got back to Brighton, Clearleft assembled as small squad to work on the project. Jon would handle the visual design, with the branding work of Dojo4 as a guide. For the front-end coding, we brought in some outside help. Seeing as the main deliverable for this project was going to be a front-end style guide, who better to put that together than the person who literally wrote the book on front-end style guides: Anna.

I’ll go into more detail about the technical side of things on the Clearleft blog (and we’ll publish the pattern library), but for now, let me just say that the project was a lot of fun, mostly because the people we were working with at Code for America—Mike, Dana, and Cyd—were so ridiculously nice and easy-going.

Anna and Jon would start the day by playing the unofficial project theme song and then get down to working side-by-side. By the end of the day here in Brighton, everyone was just getting started in San Francisco. So the daily “stand up” conference call took place at 5:30pm our time; 9:30am their time. The meetings rarely lasted longer than 10 or 15 minutes, but the constant communication throughout the project was invaluable. And the time difference actually worked out quite nicely: we’d tell them what we had been working on during our day, and if we needed anything from them; then they could put that together during their day so it was magically waiting for us by the next morning.

It’ll be a while yet before the new site rolls out, but in the meantime they’ve put together an alpha site—with a suitably “under construction” vibe—so that anyone can help out with the code and content by making contributions to the github repo.

Tagged with

codeforamerica

clearleft

design

development

process

patterns

styleguide

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

January 16, 2014

Connections

There’s a new event in town (“town” being Brighton). It’s called Connections and the first event takes place on February 4th.

Actually, it’s not really that new. Connections has been carved from the belly of Skillswap.

When Skillswap first started, it really was about swapping skills. A group of 9-12 people would get together for about three hours to learn how to use Photoshop, or write code with JavaScript. Over time, Skillswap changed. The audience grew, and the format changed: two back-to-back talks followed by a discussion. The subject matter changed too. It became less about practical skills and more thinky-thinky.

After a while, it got somewhat tedious to have to explain to potential speakers and attendees that they should “just ignore the name—it’s not really about swapping skills.”

Hence, Connections; a much more appropriate name. And yes, it is a nod to Saint James of Burke.

Connections Number One is called Weak Signals. The speakers will be Honor Harger and Justin Pickard. Honor will talk about dark matter. Justin will talk about solarpunk. See the connection?

Connections will take place in the comfy, cosy surrounding of the auditorium in 68 Middle Street. That happens to be downstairs from the Clearleft office, which makes it very convenient for me.

Tickets are available now. They’re free. But if you grab a ticket, you’d better show up. If you can’t make it, please let us know—either me or James—so that we can pass the place along to someone else. If you have a ticket, and you don’t tell us you can’t make, and then you don’t show up, you won’t be able to attend any future editions of Connections …and that would be a real shame, because this is going to be a jolly good series of events.

Tagged with

connections

brighton

event

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

January 15, 2014

Hackfarming Tiny Planner

Towards the end of each year, we Clearlefties head off to a remote location in the countryside for a week of hacking on non-client work. It’s all good unclean fun.

It started two years ago when we made Map Tales. Then last year we worked on the Politmus project. A few months back, it was the turn of Hackfarm 2013.

This time it was bigger than ever. Rather than having everyone working on one big project all week, it made more sense to split into smaller teams and work on a few different smaller projects. Ant has written a detailed description of what went down.

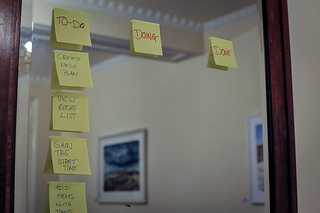

By the middle of the week, I found myself on a team with James, other James, Graham, and an Andy. We started working on something that Boxman has wanted for a while now: a simple little app for adding steps to a list of things to do.

Here’s what differentiates it from the many other to-do list apps out there: you start by telling it what time you want to be finished by. Then, after you’ve added all your steps, it tells you what time you need to get started. An example use case would be preparing a Sunday roast. You know all the steps involved, and you know what time you want to sit down to eat, so what time do you need start your preparation?

We call it Tiny Planner. It’s not “done” in any meaningful sense of the word, and let’s face it, it probably never will be. What happens at hackdays, stays at hackdays …unfinished. Still, the code is public if anyone fancies doing something with it.

What made this project interesting from my perspective, was that it was one of them new-fangled single-page-app thingies. You know the kind: the ones that are made without progressive enhancement, and cease to exist in the absence of JavaScript. Exactly the kind of thing I would normally never work on, in other words.

It was …interesting. I though it would be a good opportunity to evaluate all the various JS-or-it-doesn’t-happen frameworks like Angular, Ember, and Backbone. So I started reading the documentation. I guess I hadn’t realised quite how stupid I am, because I couldn’t make any headway. It was quite dispiriting. So I left Graham to do all the hard JavaScript work and concentrated on the CSS instead. So much for investigating new technologies.

Partly because the internet connection at Hackfarm was so bad, we decided to reduce the server dependencies as much as possible. In the end, we didn’t need any server at all. All the data is stored in the browser in local storage. A handy side-effect of that is that we could offline everything—this may one of the few legitimate uses of appcache. Mind you, I never did get ‘round to actually adding the appcache component because, well, you know what it’s like with cache-invalidation and all that. (And like I said, the code’s public now so if it ever does get put into a presentable state, someone can add the offline stuff then.)

From a development perspective, it was an interesting experiment all ‘round; dabbling in client-side routing, client-side templating, client-side storage, client-side everything really. But it did feel …weird. There’s something uncanny about building something that doesn’t have proper URLs. It uses web technologies but it doesn’t really feel like it’s part of the web.

Anyway, feel free to play around with Tiny Planner, bearing in mind that it’s not a finished thing.

I should really put together a plan for finishing it. If only there were an app for that.

Tagged with

clearleft

hackfarm

hacking

tinyplanner

development

hack

offline

javascript

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

January 14, 2014

Chüne

We’ve had an internship programme at Clearleft for a few years now, and it has served us in good stead. Without it, we never would have had the pleasure of working with Emil, Jon, Anna, Shannon, and other lovely, lovely people. Crucially, it has always been a paid position: I can’t help but feel a certain level of disgust for companies that treat interns as a source of free manual labour.

For the most recent internship round, Andy wanted to try something a bit different. He’s written about it on the Clearleft blog:

So this year we decided to try a different approach by scouring the end of year degree shows for hot new talent. We found them not in the interaction courses as we’d expected, but from the worlds of Product Design, Digital Design and Robotics. We assembled a team of three interns , with a range of complementary skills, gave them a space on the mezzanine floor of our new building, and set them a high level brief to create a product that turned an active digital behaviour into a passive one.

The three interns were Killian, Zassa, and Victor—thoroughly lovely chaps all. It was fun having them in the office—and at Hackfarm—especially as they were often dealing with technologies beyond our usual ken: hardware hacking, and the like. They gave us weekly updates, and we gave them feedback and criticism; a sort of weekly swoop’n’poop on all the work they had been doing.

It was fascinating to watch the design process unfold, without directly being a part of it. At the end of their internship, they unveiled Chüne. They describe it as:

…a playful social music service that intelligently curates playlists depending on who is around, and how much fun they’re having.

They specced it out, built a prototype, and walked us through the interactions involved. It’s a really nice piece of work.

You can read more about it around the web:

An Ingeniously Designed Speaker That Creates Crowdsourced Playlists on Wired.

Social Radio : Let’s Talk about Chüne with Victor Johansson on The Globe’s Finest Treasures.

Victor has written about the experience from his perspective, concluding:

Clearleft is by far the nicest company and working environment I have come across. All I can say is, if you are thinking about applying for next years internship programme, then DO IT, and if you aren’t thinking about it, well maybe you should start thinking!

Aw, isn’t that nice?

Tagged with

clearleft

interns

chune

design

hardware

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

January 10, 2014

Writing from home

I’m not saying that this is a trend (the sample size is far too small to draw any general conclusions), but I’ve noticed some people make a gratifying return to publishing on their own websites.

Phil Coffman writes about being home again:

I wasn’t short on ideas or thoughts, but I had no real place to express them outside of Twitter.

I struggled to express my convictions on design and felt stifled in my desire to share my interests like I once had.

I needed an online home again. And this is it.

Tim Kadlec echoes the importance of writing:

Someone recently emailed me asking for what advice I would give to someone new to web development. My answer was to get a blog and write.

Write about everything. It doesn’t have to be some revolutionary technique or idea. It doesn’t matter if someone else has already talked aobut it. It doesn’t matter if you might be wrong—there are plenty of posts I look back on now and cringe. You don’t have to be a so called “expert”—if that sort of label even applies anymore to an industry that moves so rapidly. You don’t even have to be a good writer!

Writer Neil Gaiman is taking a hiatus from Twitter, but not from blogging:

I’m planning a social media sabbatical for the first 6 months … It’s about writing more and talking to the world less. It’s time.

I plan to blog here MUCH more, as a way of warming up my fingers and my mind, and as a way of getting important information out into the world. I’m planning to be on Tumblr and Twitter and Facebook MUCH less.

If you are used to hanging out with me on Tumblr or Twitter or Facebook, you are very welcome here. Same me, only with more than 140 characters. It’ll be fun.

Joschi has been making websites for 14 years, and just started writing on his own website, kicking things off with an epic post:

I know that there will be a lot of work left when I’m going to publish this tomorrow. But in this case, I believe that even doing it imperfectly is still better than just talking about it.

That’s an important point. I’ve watched as talented, articulate designers and developers put off writing on their own website because they feel that it needs to be perfect (we are own worst clients sometimes). That’s something that Greg talks about over on the Happy Cog blog:

The pursuit of perfection must be countered by the very practical need to move forward. Our world seems to be spinning faster and faster, leaving less and less time to fret over every detail. “Make, do” doesn’t give any of us license to create crap. The quality still needs to be there but within reason, within the context of priorities.

And finally, I’ll repeat what Frank wrote at the cusp of the year:

I’m doubling down on my personal site in 2014. In light of the noisy, fragmented internet, I want a unified place for myself—the internet version of a quiet, cluttered cottage in the country. I’ll have you over for a visit when it’s finished.

Tagged with

indieweb

writing

publishing

sharing

homesteading

blogging

Have you published a response to this? Let me know the URL:

Jeremy Keith's Blog

- Jeremy Keith's profile

- 55 followers