Paul Gilster's Blog, page 96

November 9, 2018

Parker Solar Probe: Already a Record Setter

Over the sound system in the grocery store yesterday, a local radio station was recapping events of the day as I shopped. The newsreader came to an item about the Parker Solar Probe, then misread the text and came out with “The probe skimmed just 15 miles from the Sun’s surface.” Yipes!

I was in the vegetable section but you could hear him all over the store, so I glanced around to see how people had reacted. Nobody as much as raised an eyebrow, which either says people tune out background noise as they shop or they have little knowledge of our star.

The correct number is 15 million miles (24,1 million kilometers), and it’s still a hugely impressive feat, but I hope the station got the story right later on. I go easy on this kind of thing because it’s easy enough to make a mistake when reading radio copy (I’ve done this myself). Anyway, there is always some listener who calls it in, which I should have but didn’t. I was pushed for time that morning, making choices about squash and rutabagas and thinking about close approaches.

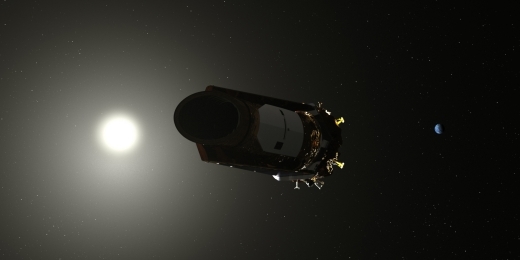

Image: Artist’s concept of the Parker Solar Probe spacecraft approaching the sun. The spacecraft will provide new data on solar activity and make critical contributions to our ability to forecast major space-weather events that impact life on Earth. Credit: NASA/JHU/APL.

After the Parker Solar Probe’s close pass, the spacecraft has gone nearer the Sun than any other craft. The Helios B probe was the previous recorder holder, setting the mark back in 1976. Helios B reached perihelion in April of 1976 at a distance of 43.4 million kilometers (26.9 million miles), inside the orbit of Mercury. A record the Parker probe surpassed with ease.

And the good news about Parker, reflected in the faces in the image below, is that the craft handled the heat and solar radiation without damage. Four status beacon signals are available, the best being the A signal that was received by mission controllers at JHU/APL on the late afternoon of November 7. Our latest mission to the Sun is live and collecting data.

Image: Members of the Parker Solar Probe mission team celebrate on Nov. 7, 2018, after receiving a beacon indicating the spacecraft is in good health following its first perihelion. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Ed Whitman.

Parker is also setting speed records. Again we turn to Helios-B as the previous record-holder, at 70.2 km/s (157,078 mph). At perihelion on November 7, the Parker spacecraft reached 213,200 miles per hour, or 95.3 kilometers per second. By way of comparison, Voyager 1 moves at approximately 17 kilometers per second as it continues to push into interstellar space. Still in the heliosheath, sister spacecraft Voyager 2 is at a slightly more sedate 15.4 km/sec.

But back to the Parker Solar Probe, whose Sun-facing Thermal Protection System, an 11-centimeter thick carbon-carbon composite shield, reached about 820 degrees Fahrenheit, or 437 degrees Celsius. This is just the beginning, for the spacecraft will continue making closer and closer approaches in the course of its 7-year mission. 24 passes by the Sun are anticipated. The spacecraft will eventually close to a scorching 6.2 million kilometers from our star.

Deep space implications? The Parker Solar Probe’s findings will teach us much about the plasma flow leaving the Sun, a solar ‘wind’ that may offer future magnetic sails (magsails) one option for reaching high velocities within the Solar System (though we first must determine whether this highly variable flow can be efficiently exploited by future magsail designs).

The other implication is using a close solar pass in a ‘sundiver’ mission, accelerating a large payload that would be flung outbound in a spectacular gravitational assist, reaching velocities in the hundreds of kilometers per second. We’ll gain a great deal of knowledge about operations close to the Sun through the performance of Parker’s heat shield, all of which should be helpful if we do decide to explore sundiver options for reaching into the Kuiper Belt and beyond.

November 8, 2018

Fine-Tuning Mechanisms for Water Delivery

We’ve long been interested in how the Earth got its oceans, with possible purveyors being comets and asteroids. The idea trades on the numerous impacts that occurred particularly during the Late Heavy Bombardment some 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago. Tuning up our understanding of water delivery is important not only for our view of our planet’s development but for its implications in exoplanet systems with a variety of different initial conditions.

Image: This view of Earth’s horizon was taken by an Expedition 7 crewmember onboard the International Space Station, using a wide-angle lens while the Station was over the Pacific Ocean. Credit: NASA.

But the picture becomes more complex when we compare regular hydrogen atoms (one proton, one electron) with ‘heavy hydrogen,’ or deuterium atoms. The latter have a neutron in addition to a proton in the nucleus. A recent paper in the Journal of Geophysical Research digs into isotope ratios, the ratio of deuterium to ordinary hydrogen atoms, commonly referred to as the D/H ratio. One reason asteroids are favored by some scientists as the likely source of the bulk of Earth’s water is that asteroidal water has a D/H in the neighborhood of 140 parts per million. Contrast that with cometary water, which runs from 150 ppm to as high as 300 ppm.

When we examine Earth’s oceans, we find a D/H ratio close to that found in asteroids. The new study, from Jun Wu and colleagues at the School of Molecular Sciences and School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, takes aim at the asteroid explanation, not by way of discounting it but rather of finding other sources making a contribution to Earth’s water.

“It’s a bit of a blind spot in the community,” said ASU’s Steven Desch, a co-author of the new study. “When people measure the [deuterium-to-hydrogen] ratio in ocean water and they see that it is pretty close to what we see in asteroids, it was always easy to believe it all came from asteroids.”

We are learning, however, that too uncritical an acceptance of D/H ratios may oversimplify the issue. For the hydrogen in Earth’s oceans is not necessarily representative of hydrogen deeper inside the planet, where D/H ratios close to the boundary between the core and mantle show considerably less deuterium. This may indicate a non-asteroidal source for at least some of the hydrogen.

Another telling point is that helium and neon, showing isotopic signatures inherited from the original solar nebula, have also been found in Earth’s mantle. Contrasting hydrogen at the core-mantle boundary with what we see in Earth’s oceans and factoring in these noble gases may change our thinking. The Wu study considers the formation of the planets in the earliest days of the Solar System, when small, often colliding planetary embryos up to the size of Mars went through gradual planetary accretion.

The new model works like this: As larger embryos formed largely from water-laden asteroids, they began to develop into planets. On Earth, decaying radioactive elements melted iron within the emerging world, pulling in asteroidal hydrogen and sinking to form a core. Collisions among planetesimals would meanwhile have created enough energy to melt the surfaces of the larger embryos like the Earth into magma oceans.

Hydrogen and noble gases from the solar nebula would be drawn in to create an early atmosphere. The nebular hydrogen, lighter than asteroidal hydrogen, would have dissolved into the molten iron of the magma ocean, eventually being drawn into the mantle, along with hydrogen from other sources.

What the authors argue is that this process created a slight enrichment of hydrogen in the molten iron and left a higher ratio of deuterium behind in the magma (the process is called isotopic fractionation). Hydrogen is attracted to iron, while the heavier isotope, deuterium, less attracted to iron, would have remained in the magma which would eventually become Earth’s mantle. We would end up with lower D/H ratios in the core than in the mantle and oceans. The authors argue that while most of Earth’s water is asteroidal, some of it did in fact come from the solar nebula.

The process is complex, and also takes in impacts from smaller embryos and other objects that continued to add water and mass until Earth reached its final size. The authors provide this synopsis as their caption for Figure 1 (above), which I’ll reproduce verbatim but break into sections for reasons of readability:

(a) Earth accreted from embryos with chondritic [asteroidal] levels of water concentrations and D/H ratios.

(b) These embryos differentiated and stored relatively light hydrogen in their cores, raising the D/H of hydrogen in their mantles.

(c) The largest embryo accreted a proto-atmosphere and sustained a magma ocean into which nebular hydrogen diffused.

(d) The largest embryo’s magma ocean crystallized and overturned, mixing light hydrogen into the mantle, but incompletely.

(e) As smaller embryos were accreted, their mantles joined the proto‐Earth’s mantle, and their cores merged with the proto‐Earth’s core.

The result is:

(f) Earth’s mantle today contains approximately three oceans of water in its mantle and surface, with average D/H ≈ 150 × 10−6, and ~4.8 oceans’ worth of hydrogen in its core, with D/H ≈ 130 × 10−6. Mantle plumes can sample low‐D/H material from the core‐mantle boundary.

Wu says this: “For every 100 molecules of Earth’s water, there are one or two coming from [the] solar nebula.” But we now see the potential for including gas left over from the formation of our Solar System in the question of water delivery and accumulation. In other stellar systems where water-bearing asteroids may not be as abundant, this implies that water could still be in place from the system’s own stellar nebula. Wu adds: “This model suggests that the inevitable formation of water would likely occur on any sufficiently large rocky exoplanets in extrasolar systems. I think this is very exciting.”

The paper concludes:

Our comprehensive model for the origin of Earth’s water considers, for the first time, the effects of isotopic fractionation as hydrogen dissolved into metal and was sequestered into the core. Based on the behaviors of proxies, we consider it likely that the D/H ratio of the core is ~10% lighter than the mantle. We hypothesize that Earth accreted a few to tens of oceans of water from chondrites, mostly carbonaceous chondrites. Drawing on the latest theories of planet formation, which argue for rapid (

The paper is Wu et al., Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 09 October 2018 (full text).

November 7, 2018

On the Earliest Stars

If you’ve given some thought to the Fermi question lately — and reading Milan Ćirković’s The Great Silence, I’ve been thinking about it quite a bit — then today’s story about an ancient star is of particular note. Fermi, you’ll recall, famously wanted to know why we didn’t see other civilizations, given the apparent potential for our galaxy to produce life elsewhere. Now a paper in The Astrophysical Journal adds punch to the question by making the case that the part of the galaxy in which we reside may be older than we have thought.

Finding that our Sun is younger than many nearby stars, an issue that Charles Lineweaver (Australian National University), among others, has examined, would allow even more time for civilizations to have emerged in the galactic neighborhood. But let’s now leave Fermi behind to look at the tiny star that prompts these ruminations (and to be sure, the paper on this star makes no mention of Fermi, but does tell us something quite interesting about the early cosmos).

Discovered by Kevin Schlaufman (Johns Hopkins University), 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B is the smaller of a binary pair that orbit a common barycenter. While the primary had been previously discovered, it was up to Schlaufman and team to uncover the far more interesting companion.

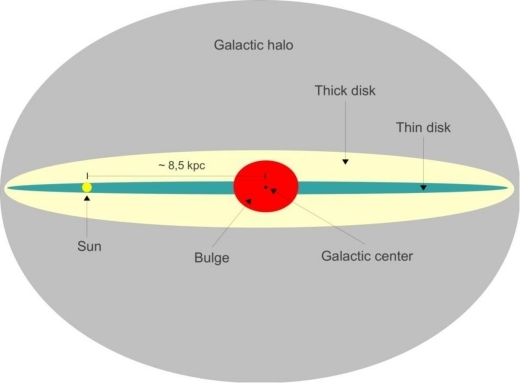

Schlaufman used data from the Magellan Clay Telescope, Las Campanas Observatory and the Gemini Observatory in finding and characterizing this star. What distinguishes 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B is its size, metallicity and age. On the latter, Schlaufman believes it could be as little as a single generation removed from the Big Bang itself, and the paper pegs its age at approximately 13.5 billion years. We’ve discovered other ancient stars with low metal content, but this one is located in the Milky Way’s thin disk, that part of the galaxy in which we reside. Hence the issue of the age of local stars, as the paper recounts:

Given its thin disk orbit, the 13.535 ± 0.002 Gyr age of the 2MASS J18082002–5104378 system provides a lower limit on the age of the thin disk. Similarly old but not quite as metal-poor stars have also been seen on thin disk orbits (e.g., Casagrande et al. 2011; Bensby et al. 2014). This is somewhat older than the 8–10 Gyr age of the thin disk suggested by classical studies of field stars (Edvardsson et al. 1993; Liu & Chaboyer 2000; Sandage et al. 2003), the white dwarf luminosity function (e.g., Oswalt et al. 1996; Leggett et al. 1998; Knox et al. 1999; Kilic et al. 2017), and the ages of the oldest disk open clusters Berkeley 17 and NGC 6791 (e.g., Krusberg & Chaboyer 2006; Brogaard et al. 2012).

Image: This edge-on diagram of the Milky Way shows the thin disk in green. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

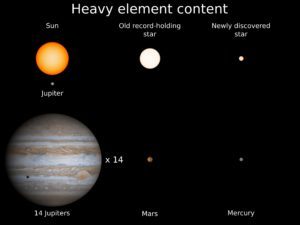

We are talking about a star with a content of metals roughly the same as the planet Mercury. Contrast that with the Sun, whose heavy element content is equal to approximately 14 Jupiters.

2MASS J18082002–5104378 B (here’s hoping it gets a new moniker, perhaps ‘Schlaufman’s Star’) is the lowest-mass ultra metal-poor star currently known. Yet despite its extreme age and low metallicity, it is found in the thin disk, and in fact is the most metal-poor star yet found that is part of the thin disk. We would expect stars forming not long after the Big Bang to be low in metals, given that hydrogen, helium and trace lithium are all they had to work with. It would be later stellar generations that could form with the heavier elements these early stars produced in their cores, seeding the cosmos with metals through supernovae explosions.

Call that first generation Population III stars, which when first modeled by researchers produced stars far more massive than the Sun, giant objects that should form as single stars in isolation. Later models dropped the range of mass to as low as 10 solar masses but also extended it on the high end. Low-mass Population III stars only recently began to be considered when the issue of fragmentation began appearing in numerical simulations. The discovery of 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B makes the case for the emergence of such stars.

From the paper:

We use models of protostellar disks around both UMP [low-mass ultra metal-poor] and Pop III protostars plus scaling relations for the fragment mass and migration time to argue that the existence of the low-mass UMP star 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B and the extremely metal-poor (EMP) brown dwarf HE 1523–0901 B discovered by Hansen et al. (2015) implies the survival of solar-mass fragments around Pop III stars…

Thus we may be looking at a new observable that can take us back to conditions at the earliest era of star formation:

Whereas fragmentation at the molecular core scale will likely lead to massive binary stars, the emergence of gravitationally bound solar-mass clumps in protostellar disks via gravitational instability has the potential to produce low-mass Pop III stars that may be observable in the Milky Way.

Image: The new discovery is only 14% the size of the Sun and is the new record holder for the star with the smallest complement of heavy elements. It has about the same heavy element complement as Mercury, the smallest planet in our solar system. Credit: Kevin Schlaufman/JHU.

Thus far about 30 stars considered ultra metal-poor have been identified, all of roughly the Sun’s mass, but 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B is only 14 percent of the Sun’s mass. The mass, incidentally, was determined by radial velocity methods, examining the wobble of the primary star. Backing out to the wider picture, our view of the earliest stars as extremely massive objects, unobservable to us because they would have burned quickly and died, has to be modified to include low-mass stars that can, at least in some situations, emerge, as 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B did, burning for long lifetimes indeed. Says Schlaufman:

“If our inference is correct, then low-mass stars that have a composition exclusively the outcome of the Big Bang can exist. Even though we have not yet found an object like that in our galaxy, it can exist.”

The paper is Schlaufman et al., “An Ultra Metal-poor Star Near the Hydrogen-burning Limit,” Astrophysical Journal Vol. 867, No. 2 (5 November 2018). Abstract / preprint.

November 6, 2018

SETI in the Infrared

One of the problems with optical SETI is interstellar extinction, the absorption and scattering of electromagnetic radiation. Extinction can play havoc with astronomical observations coping with gas and dust between the stars. The NIROSETI project (Near-Infrared Optical SETI) run by Shelley Wright (UC-San Diego) and team is a way around this problem. The NIROSETI instrument works at near-infrared wavelengths (1000 – 3500 nm), where extinction is far less of a problem. Consider infrared a ‘window’ through dust that would otherwise obscure the view, an advantage of particular interest for studies in the galactic plane.

Would an extraterrestrial civilization hoping to communicate with us choose infrared as the wavelength of choice? We can’t know, but considering its advantages, NIROSETI’s instrument, mounted on the Nickel 1-m telescope at Lick Observatory, is helping us gain coverage in this otherwise neglected (for SETI purposes) band. I had the chance to talk to Dr. Wright at one of the Breakthrough Discuss meetings in Palo Alto, where she made a fine presentation on the subject. Since then my curiosity about infrared SETI has remained high.

Meanwhile, at MIT…

Then this morning I came across graduate student James Clark, who has just published a paper on interstellar beacons in the infrared in the Astrophysical Journal. Working at MIT’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Clark is not affiliated with NIROSETI. He’s wondering what it would take to punch a signal through to another star, and concludes that a large infrared laser and a telescope through which to focus it would be the tools of choice.

The goal: An infrared signal at least 10 times greater than the Sun’s natural infrared emissions, one that would stand out in any routine astronomical observation of our star and demand further study. Clark believes that a 2-megawatt laser working in conjunction with a 30-meter telescope would produce a signal easily detectable at Proxima Centauri b, while a 1-megawatt laser working through a 45-meter telescope would produce a clear signal at TRAPPIST-1.

But nearby stars are just the beginning, for in Clark’s view, either of these setups would produce a signal that could be detected up to 20,000 light years away, almost to galactic center. All of this may remind you of Philip Lubin’s work, recently described here, on laser propulsion. Depending on the system in play, one of Lubin’s DE-STAR 4 beams would be observed as the brightest star in the sky from 1000 light years away (see Trillion Planet Survey Targets M-31 for more on this). The NIROSETI website makes the same observation about laser visibility:

The most powerful laser beams ever created (e.g. LFEX) can produce optical pulses with 2 petawatts (2.1015W) peak power for an incredibly short duration, approximately one picosecond. Such lasers would outshine our sun by several order of magnitudes if seen by a distant receiver. It can be shown that strong pulsed signals at nanosecond (or faster) intervals can be distinguishable from any known astrophysical sources.

Image: An MIT study proposes that laser technology on Earth could emit a beacon strong enough to attract attention from as far as 20,000 light years away. Credit: MIT.

The kind of system Clarke is talking about is not beyond our capabilities even now:

“This would be a challenging project but not an impossible one,” Clark says. “The kinds of lasers and telescopes that are being built today can produce a detectable signal, so that an astronomer could take one look at our star and immediately see something unusual about its spectrum. I don’t know if intelligent creatures around the sun would be their first guess, but it would certainly attract further attention.”

In terms of current capabilities, we can think about Clark’s 30-meter telescope in relation to plans for telescopes as huge as the 39-meter European Extremely Large Telescope, now under construction in Chile, or the likewise emerging 24-meter Giant Magellan Telescope. How and where to build such a laser is the same sort of issue now being analyzed by Breakthrough Starshot, which conceptualizes a series of small lightsail missions to nearby stars using laser beaming. Caveats include safety issues for both humans and spacecraft equipment. Clark suggests the far side of the Moon would be the ideal place for such an installation.

With METI (Messaging to Extraterrestrial Intelligence) continuing to be controversial, to say the least, whether or not we would ever choose to build an infrared laser as an interstellar beacon is up for question. But Clark’s analysis takes in the question of whether today’s technologies could detect such a signal if a civilization elsewhere put it into play and tried to communicate with us. As we’ve seen in other discussions of interstellar beacons, detection is highly problematic.

“With current survey methods and instruments, it is unlikely that we would actually be lucky enough to image a beacon flash, assuming that extraterrestrials exist and are making them,” Clark says. “However, as the infrared spectra of exoplanets are studied for traces of gases that indicate the viability of life, and as full-sky surveys attain greater coverage and become more rapid, we can be more certain that, if E.T. is phoning, we will detect it.”

We don’t know whether E.T. does astronomical surveys, but we know we do, and we are rapidly moving toward the study of small, rocky exoplanets through the spectra of their atmospheres. Thus Clark’s paper could be seen as a reminder to astronomers that an unusual signal could lurk within their infrared data, one that we should at least be aware of and prepared to analyze. A conversation between nearby stars at a data rate of a few hundred bits per second could eventually result.

The paper is Clark, “Optical Detection of Lasers with Near-term Technology at Interstellar Distances,” Astronomical Journal Vol. 867, No. 2 (5 November 2018). Abstract.

November 5, 2018

Bennu Coming into Focus

Following a week when we learned of the end of both Kepler and Dawn, let’s turn to a mission that is just coming into its own. The earliest images of target asteroid 101955 Bennu from OSIRIS-REx have been tightened by computer algorithm to heighten their resolution. The mission plan here is to examine the small object (approximately 500 meters in mean diameter) and return samples to Earth in 2023.

More than a few people have reacted to the similarity in shape between this asteroid, a carbonaceous (C-type) Earth-crossing object in the Apollo group of near-Earth asteroids, and 162173 Ryugu, now under active exploration by the Japanese Hayabusa2 mission. Here we’re looking at Bennu through the OSIRIS-REx PolyCam, one of three cameras aboard the spacecraft, from a distance of 330 kilometers. The image is a combination of eight images taken by PolyCam that have been combined to cancel out the asteroid’s rotation and produce a high-resolution result.

Of the comparison to Ryugu, Julia de León (Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias – IAC) says this:

“The fact that the Japanese mission has reached its target a little ahead of us turns out to be extremely interesting, as we can now interpret our results and compare to the results obtained by another mission almost on real time.”

Image: This “super-resolution” view of asteroid Bennu was created using eight images obtained by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft on Oct. 29, 2018 from a distance of about 330 km. The spacecraft was moving as it captured the images with the PolyCam camera, and Bennu rotated 1.2 degrees during the nearly one minute that elapsed between the first and the last snapshot. The team used a super-resolution algorithm to combine the eight images and produce a higher resolution view of the asteroid. Bennu occupies about 100 pixels and is oriented with its north pole at the top of the image. Date Taken: Oct. 29, 2018. Instrument Used: OCAMS (PolyCam). Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona.

The team from the IAC, which functions as part of the Image Processing Working Group (IPWG) for the OSIRIS-REx mission, is examining the early imagery from Bennu as an initial step in calibrations for comparison with later, higher-resolution images taken with color filters. In December, images from the spacecraft’s MapCam will begin coming in, putting those filters to work. The color maps thus generated will be used to break down the geographical distribution of silicates and other materials on the asteroid. And, of course, they will also play into the selection of a landing site from which a sample will be collected and returned to Earth.

OSIRIS-REx executed its third asteroid approach maneuver (AAM-3) on October 29, a set of thruster burns designed to slow the craft relative to Bennu from approximately 5.2 m/sec to .11 m/sec. The maneuver, verified by tracking data and telemetry, was designed to maximize the collection of high-resolution images as the spacecraft closes on the target. Another burn, the fourth in a series that began on October 1, will be executed on November 12, adjusting the craft’s trajectory for arrival at a position some 20 kilometers from Bennu on December 3.

And here’s another interesting image, a look at both Bennu and Jupiter, as seen by the OSIRIS-REx Polycam. The shot of Bennu was taken on October 22 of this year, with Bennu some 3,650 kilometers away, while the Jupiter image was captured on February 12, 2017 at a distance of 673 million kilometers. Notice the clear spherical shape of Jupiter as compared to the diamond-shaped Bennu, a shape predicted by ground-based radar observations.

Image: When these images were taken, Bennu was about five times closer to the Sun than Jupiter was, so the asteroid was receiving significantly more sunlight. If Bennu and Jupiter were equally reflective, the asteroid would appear about 25 times brighter in this image due to its proximity to the Sun. But Bennu’s surface is so dark (only reflecting about 3 to 4 percent of the incoming sunlight) that it appears darker than Jupiter despite being much closer to the Sun. Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona.

Carbonaceous C-type asteroids, as the image makes clear in this case, are low in albedo, presumably because of the large amount of carbon mixing with surface rocks and minerals.

If you’re tracking this mission closely, be aware of email updates that are available and check Twitter @OSIRISREx, Instagram or Facebook for more.

How many times is too many times to ask #AreWeThereYet on a single trip? Asking for a friend (who is now only a couple hundred kilometers from #asteroid Bennu)…

More on my whereabouts: https://t.co/rACre4nDe4 pic.twitter.com/tJaMcHw6qP

— NASA's OSIRIS-REx (@OSIRISREx) November 5, 2018

November 2, 2018

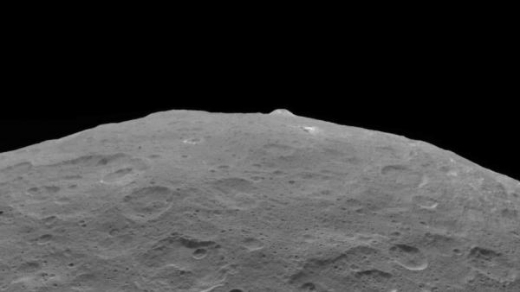

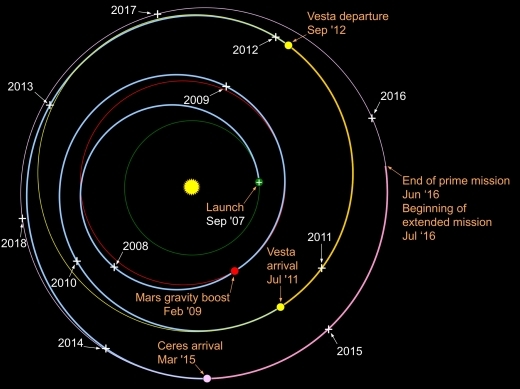

Farewell to Dawn

It seems to be a week for endings. Following the retirement of the wildly successful Kepler spacecraft, we now say goodbye to Dawn following an extraordinary eleven years that took us not only to orbital operations around Vesta but then on to detailed exploration of Ceres. The spacecraft ran out of hydrazine, with the signal being lost by the Deep Space Network during a tracking pass on Wednesday. No hydrazine means no spacecraft pointing, vital in keeping Dawn’s antenna properly trained on a distant Earth.

I immediately checked to see if mission director and chief engineer Marc Rayman had gotten off a post on his Dawn Journal site, but he really hasn’t had time to yet. It will be interesting to see what Dr. Rayman says, and it’s appropriate here to thank him for the continuing updates and insights he provided throughout the Dawn mission. Keeping space exploration in front of the public is essential for continuing funding of deep space robotic missions, as both the Dawn and New Horizons team clearly understand (and there is much ahead for New Horizons!)

Image: This photo of Ceres and one of its key landmarks, Ahuna Mons, was one of the last views Dawn transmitted before it completed its mission. This view, which faces south, was captured on Sept. 1 at an altitude of 3570 kilometers as the spacecraft was ascending in its elliptical orbit. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA.

The ability to orbit one target, move on to another and subsequently establish an orbit there is a demonstration of what ion engines can do, and a reminder of how significant the Deep Space 1 mission was in terms of testing these technologies. If DS1 established ion propulsion as a viable tool, Dawn took it to the next level, highlighting the kinds of exploration that may lie ahead as we contemplate missions to multiple Kuiper Belt objects (see Game-changer: A Pluto Orbiter and Beyond). Ambitious missions grow out of the gentle, efficient thrust of ion engines.

Ponder this: The orbiters we’ve sent to Mars had to burn their engines for orbital insertion. Consider something on the order of 300 kilograms of propellant for conventional rocketry to meet this requirement. Dawn could make the same change in speed (about 1000 meters/second) using fewer than 30 kilograms of xenon. But of course we wouldn’t use ion engines for this purpose. Ion engines demand patience: It would take Dawn three months to achieve this result while conventional engines in our orbiters complete this maneuver in 25 minutes. But missions with multiple targets or complex operations in deep space are suited to engines like Dawn’s, which accumulated 2,141 days (5.9 years) of thrust time in the course of its travels.

Describing Dawn’s changing trajectories and the intricate gravitational dance they involved, Rayman wrote this paean to ion propulsion in his Dawn Journal:

Without that technology, NASA’s Discovery Program would not have been able to afford a mission to explore the exotic world in such detail. Dawn has long since gone well beyond that. Having discovered so many of Vesta’s secrets, the adventurer left it behind. No other spacecraft has ever escaped from orbit around one distant solar system object to travel to and orbit still another extraterrestrial destination. From 2012 to 2015, the stalwart craft reshaped and tilted its orbit even more so that now it is identical to Ceres’. Once again, that was essential to accomplishing the intricate celestial choreography in which the behemoth reached out with its gravity and tenderly took hold of the spacecraft. They have been performing an elegant pas de deux ever since.

And now the mission is over, though the spacecraft will remain in Ceres orbit for at least twenty years, and mission engineers believe with 99 percent confidence that its orbit will last at least 50 years, keeping planetary protection protocols in place for the near future. As we look back, consider Dawn’s accomplishments. It was the first spacecraft to orbit a body between Mars and Jupiter, the first to visit a dwarf planet and the first to orbit two destinations beyond Earth.

Image: Dawn’s interplanetary trajectory (in blue). The dates in white show Dawn’s location every Sept. 27, starting on Earth in 2007. Note that Earth returns to the same location, taking one year to complete each revolution around the Sun. When Dawn is farther from the Sun, it orbits more slowly, so the distance from one Sept. 27 to the next is shorter. Credit: NASA/JPL.

“In many ways, Dawn’s legacy is just beginning,” said principal investigator Carol Raymond at JPL. “Dawn’s data sets will be deeply mined by scientists working on how planets grow and differentiate, and when and where life could have formed in our solar system. Ceres and Vesta are important to the study of distant planetary systems, too, as they provide a glimpse of the conditions that may exist around young stars.”

Dawn’s discoveries at Vesta and Ceres have been described before in these pages, but we’ll track new conclusions from Dawn’s datasets well into the future. For now, I’m simply thinking about Dawn’s beginnings and all that has happened since. Congratulations to the entire team.

Image: Dawn climbs to space on Sept. 27, 2007, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Dawn launched at dawn (7:34 am EDT). Credit: KSC/NASA.

November 1, 2018

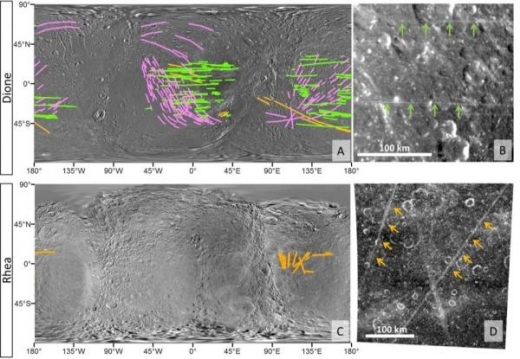

The Stripes of Dione

Usually when we talk about outer planet moons with oceans, we’re looking at Jupiter’s Europa, and Saturn’s Enceladus. But evidence continues to mount for oceans elsewhere. In the Jupiter system alone, Callisto and Ganymede are likewise strong candidates, while Saturn’s Titan probably has a layer of liquid water. Pluto’s moon Charon may possess an ocean of water and ammonia, to judge from what appears to be cryovolcanic activity there. At Neptune, Triton’s high-inclination orbit should produce plenty of tidal heating that may support a subsurface ocean.

Let’s pause, though, on another of Saturn’s moons, Dione. Here we have evidence from Cassini that this world, some 1120 kilometers in diameter and composed largely of water ice, has a dense core with an internal liquid water ocean, joining Enceladus in that interesting system. But what engages us this morning is not liquid water but a set of straight, bright stripes discovered on the surface and discussed in a new paper from Alex Patthoff (Planetary Science Institute) and Emily Martin (Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, Smithsonian Institution).

The term being used for these lines is linear virgae, linear ‘stripes’ of color, that are apparently the result of interactions with Saturn’s rings and, possibly, the co-orbital moons Helene and Polydeuces (the latter follows Dione at its trailing Lagrangian point, the former orbiting at the leading L4 Lagrangian point).

“The evidence preserved in the linear virgae has implications for the orbital evolution and impact processes within the Saturnian system,” says Patthoff. “Plus, the interaction of Dione’s surface and exogenic material has implications for its habitability and provides evidence for the delivery of ingredients that may contribute to the habitability of ocean worlds in general.”

Image: Distribution of linear virgae on Dione and Rhea. Shown are the distribution of linear virgae (green) crater rays (pink) and candidate linear virgae (orange) a. Global distribution of linear virgae, crater rays, and candidate linear virgae on Dione. b. Detailed view of linear virgae (green arrows) on Dione. Image No. N1649318802 centered at 22°W, 10°N. c. Global distribution of candidate linear virgae on Rhea. d. Detailed view of candidate linear virga. Credit: A) Basemap from Roatsch et al, 2008. B) Image No. N1649318802. C) Basemap from Roatsch et al, 2012. D) Image No. N1673420688.

The linear virgae on Dione range between 10 and hundreds of kilometers in length and less than 5 kilometers in width, showing up as substantially brighter than the surrounding terrain. Interestingly, they’re also parallel and appear to overlay other surface features, an indication of their relative youth compared to surrounding topography. Patthoff again:

“Their orientation, parallel to the equator, and linearity are unlike anything else we’ve seen in the solar system. If they are caused by an exogenic source, that could be another means to bring new material to Dione. That material could have implications for the biological potential of Dione’s subsurface ocean.”

Thus we have another potential habitat for biology beneath an icy moon’s crust. Cassini imagery showed inactive fractures at Dione similar to those found at Enceladus, and the spacecraft’s magnetometer also detected a faint particle stream coming from the moon. In 2013, Noah Hammond (Brown University) and colleagues examined the Janiculum Dorsa mountain and ridgeline in Cassini data, finding that the moon’s crust seemed to have flexed beneath the mountain, an indication of a subsurface ocean and warm crust at least at the time the area formed. Why Enceladus is so active in comparison to Dione is an open question.

Image: Although Dione (near) and Enceladus (far) are composed of nearly the same materials, Enceladus has a considerably higher reflectivity than Dione. As a result, it appears brighter against the dark night sky. The surface of Enceladus (504 kilometers across) endures a constant rain of ice grains from its south polar jets. As a result, its surface is more like fresh, bright, snow than Dione’s (1123 kilometers across) older, weathered surface. As clean, fresh surfaces are left exposed in space, they slowly gather dust and radiation damage and darken in a process known as “space weathering.” This view looks toward the leading hemisphere of Enceladus. North on Enceladus is up and rotated 1 degree to the right. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Sept. 8, 2015. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

The paper is Martin & Patthoff, “Mysterious Linear Features Across Saturn’s Moon Dione,” Geophysical Research Letters 15 October 2018 (abstract). The Hammond paper is “Flexure on Dione: Investigating subsurface structure and thermal history,” Icarus Vol. 223, Issue 1, (March 2013), pp. 418–422 (abstract).

October 31, 2018

Thoughts on the End of the Kepler Mission

The Kepler spacecraft has been with us long enough (it launched in 2009) and has revealed so much about the stars in our galaxy that its retirement — Kepler lacks the fuel for further science operations — is cause for reflection. The end of great missions always gives us pause as we consider their goals and their accomplishments, and offer up our gratitude to the many people who made the mission happen. Let’s try to back up and see things in their totality.

Image: An artist’s conception of Kepler at work. Credit: NASA/Ames/Dan Rutter.

Kepler’s job was essentially statistical, an attempt to look at as many stars as possible in a particular field of stars, so that we could gain insights into the distribution of planets there, and thus deduce something about likely conditions galaxy-wide. We didn’t know in 2009 that there was statistically at least one planet around every star, nor did we know just how diverse the worlds Kepler found, more than 2,600 of them, would be. Moreover, Kepler pushed the bounds of the possible with an ingenious extended mission.

After the mission was extended in 2012, engineers had to work around gyroscope failures to use solar photon pressure to keep the spacecraft pointed. The so-called ‘K2’ mission left the fixed view to move around the sky, studying 19 different patches of it and thus producing entirely different datasets. As with any mission, we’ve accumulated such extensive information that papers from Kepler data will be coming out for decades to come. Using the transit method to detect the passage of planets across the face of their star, Kepler’s planetary survey, originally studying over 156,000 stars, would move on through K2 to cover more than 500,000.

We have a great deal to learn as we carry Kepler discoveries forward, but it now seems likely that somewhere between 20 and 50 percent of all visible stars have rocky planets in the habitable zone of their stars. ‘Super Earths’ turned out to be the most common size of planet Kepler found, worlds between Earth and Neptune in size. Unless we find a hitherto undiscovered world deep in our outer system, we have no examples of such planets around Sol.

Interestingly, we’ve also learned how common compact planetary systems can be. Some of the Kepler systems bear more resemblance to Jupiter and its moons than planets and their host stars. KOI-961 is a case in point. About 130 light years away in Cygnus, the star is an M-dwarf about 70 percent larger than Jupiter, orbited by three small and likely rocky planets, all three of which orbit their host in less than two days.

Image: This illustration depicts NASA’s exoplanet hunter, the Kepler space telescope. The agency announced on Oct. 30, 2018, that Kepler has run out of fuel and is being retired within its current and safe orbit, away from Earth. Kepler leaves a legacy of more than 2,600 exoplanet discoveries. Credit: NASA/Wendy Stenzel/Daniel Rutter.

Another Kepler find: Kepler-11, approximately 2000 light years away, with six planets, the outermost of which is twice as close to its star as the Earth is to the Sun. In fact, the five inner planets are closer to their star than Mercury is to the Sun. The list goes on: Kepler-32 is an M-dwarf with five transiting worlds orbiting within a distance that is just one-third the size of Mercury’s orbit. We now explore how such systems form and examine multi-planet systems like TRAPPIST-1 (not a Kepler discovery) that offer planets in the habitable zone.

Kepler also discovered its share of unusual exoplanets like Kepler-10b, a world with a year that lasts less than an Earth day and a density implying it is made of iron and rock, a ‘lava world.’ K2 found a planetary object around the white dwarf WD 1145+017. Kepler-16b is the first planet discovered around a double-star system, reminiscent of Tatooine in Star Wars. Kepler-444 has five planets that are 11 billion years old. And need I mention Boyajian’s Star, whose oddly fluctuating lightcurve is indicative most likely of dust clouds but was intensely studied in terms of possible alien engineering.

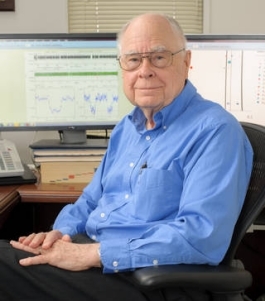

“When we started conceiving this mission 35 years ago we didn’t know of a single planet outside our solar system,” said the Kepler mission’s founding principal investigator, William Borucki, now retired from NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. “Now that we know planets are everywhere, Kepler has set us on a new course that’s full of promise for future generations to explore our galaxy.”

Image: William Borucki, principal investigator for NASA’s Kepler mission, in his office at NASA’s Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California. June 2015. Credit: NASA Ames.

Kepler kept sending us data even as it ran low on fuel, with the latest, from Campaign 19, marking a kind of handover to TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which launched back in April. All told, we pulled in 678 GB of science data in Kepler’s 9.6 years in space, leading thus far to 2,946 published scientific papers, with many more to come. Last night at a favorite restaurant my wife and friends joined me in a toast to the Kepler team, and the mission’s indefatigable PI William Borucki. An outstanding accomplishment all around.

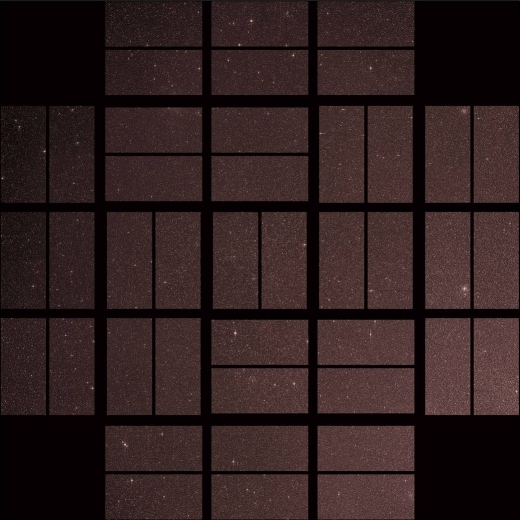

To wrap this up, here’s Kepler’s ‘first light’ image from 2009.

Image: This image from NASA’s Kepler mission shows the telescope’s “first light” — a full field of view of an expansive star-rich patch of sky in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra stretching across 100 square degrees, or the equivalent of two side-by-side dips of the Big Dipper. Credit: NASA.

October 29, 2018

‘Oumuamua, Thin Films and Lightsails

The interstellar object called ‘Oumuamua continues to inspire analysis and speculation. And no wonder. We had limited time to observe it and were unable to obtain a resolved image to find out exactly what it looks like. This morning I want to go through a new paper from Shmuel Bialy and Abraham Loeb (Harvard University) considering the role radiation pressure from the Sun could play on this deep sky wanderer. Let’s also review what we do know about it, which I’ll do with reference to this paper’s introduction, where recent work is discussed. For it seems that each time we look at ‘Oumuamua anew, we find something else to talk about.

Discovered in October of 2017 by the Pan-STARRS survey (Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System) in Hawaii, ‘Oumuamua stood out because of its hyperbolic trajectory, flagging it as an interstellar object, the first ever discovered passing through the Solar System. The object’s lightcurve indicated both that it was tumbling and had an aspect ratio of at least 5:1 and perhaps higher, an unusual shape for known asteroids and comets. I won’t provide all the references here, as they’re easily found both in the paper cited below and in other related work.

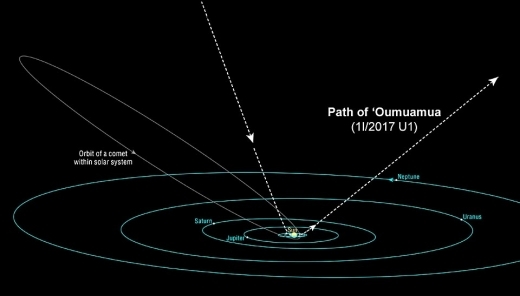

Image: The track of `Oumuamua as it passed through the inner solar system in late 2017. Credit: Brooks Bays / SOEST Publication Services / Univ. of Hawaii.

What stood out in 2018 was detection of non-gravitational acceleration in ‘Oumuamua’s motion, which could be consistent with cometary activity, although as we’ve seen in other posts on this site, no such activity has been noted by way of a cometary tail or gas emission and absorption lines. This despite a relatively close approach to the Sun of 0.25 AU. The Micheli et al. paper noting the acceleration was addressed in another 2018 paper from Rafikov et al., which pointed out that torque from any cometary outgassing should have had effects on the object’s spin, but this does not appear in our admittedly limited observations.

What Bialy and Loeb consider in today’s paper is the possibility that solar radiation pressure — imparted by the momentum of photons from the Sun — is responsible for the acceleration, expressed as an excess radial acceleration ∆a ∝ r−2, where r is the distance of ’Oumuamua from the Sun. If so, ‘Oumuamua would of necessity be a thin object with a small mass-to-area ratio — this is required in order to make the radiation pressure effective.

We can work out constraints on the object’s area through its observed magnitude. The paper proceeds to show that a thin sheet roughly 0.3 mm thick and some 20 meters in radius will allow the non-gravitational acceleration computed in the Micheli paper.

I was intrigued enough at this point to ask Dr. Loeb about those dimensions, which vary with albedo (the incident light reflected by a surface). He told me that the 20-meter figure would be the radius if the object is a perfect reflector, though the size would be larger if the value for the albedo is smaller. We do see variations in reflected light as ‘Oumuamua rotates over an eight-hour spin period. Thus, considering the object as a thin surface, we could imagine a conical or hollow cylindrical shape. “You can easily envision that by rotating a curved piece of paper and looking at its net surface area from different viewing angles,” Loeb told me.

So let’s back up a moment. We are asking what properties ‘Oumuamua would have to have if its non-gravitational acceleration is the result of solar radiation pressure. We do not know that solar radiation is the culprit, but if it is, the object would need to be a thin sheet with a width in the range of 0.3 mm. This scenario explains the acceleration but forces the question of what kind of object could have these characteristics. A major problem is that, as mentioned above, there are too many degrees of freedom in our observations to nail down what ‘Oumuamua looks like. We did not have observations sensitive enough to produce a resolved image.

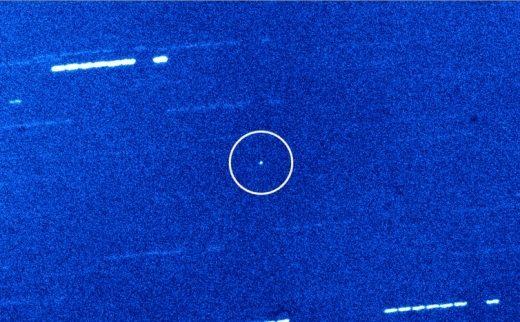

Image: Oumuamua as it appeared using the William Herschel Telescope on the night of October 29. Credit: Queen’s University Belfast/William Herschel Telescope.

We do know that if ‘Oumuamua is accelerating because of solar photons, it must represent what the paper calls ‘a new class of thin interstellar material.’ The researchers note the possibility that such material is naturally produced in the interstellar medium, but go on to consider an artificial origin. Could ‘Oumuamua be debris from a technological civilization, a discarded lightsail?

A fascinating speculation indeed. From the paper:

Considering an artificial origin, one possibility is a lightsail floating in interstellar space as debris from an advanced technological equipment (Loeb 2018). Lightsails with similar dimensions have been designed and constructed by our own civilization, including the IKAROS project and the Starshot Initiative. The lightsail technology might be abundantly used for transportation of cargos between planets (Guillochon & Loeb 2015) or between stars (Lingam & Loeb 2017). In the former case, dynamical ejection from a planetary system could result in space debris of equipment that is not operational any more (Loeb 2018) and is floating at the characteristic speed of stars relative to each other in the Solar neighborhood.

We’re past the stage where we can image ‘Oumuamua with our telescopes and it’s too late to get a mission off to chase it with chemical rockets, which means that the only way we have of pressing the investigation forward is to look for other such objects in the future. But we can look at the properties of thin films to determine whether an object like a lightsail could survive interstellar travel, given encounters with dust and gas between the stars. Returning to the paper:

Collisions with dust grains at high velocities will induce crater formation by melting and evaporation of the target material. Since the typical time between dust collisions is long compared to the solidification time, any molten material will solidify before the next collision occurs, and thus will only cause a deformation of the object’s surface material, not reduction in mass. On the other hand, atoms vaporized through collisions can escape and thus cause a mass ablation.

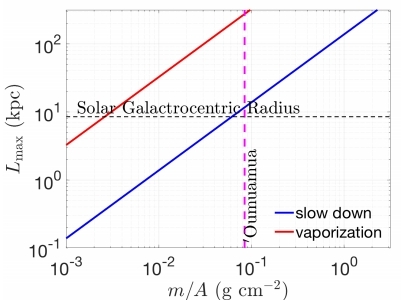

Bialy and Loeb find that for the mass-to-area ratio they have calculated for a thin-film ‘Oumuamua, the object could travel through much of the galaxy before losing a significant fraction of its mass. Collisions with gas particles in the interstellar medium as well as the stresses of centrifugal and tidal forces are also considered. None of these present problems for the object’s survival until we reach a maximal travel distance in the range of 10 kpc (well over 32,000 light years). Earth is approximately 25,000 light years from the center of the galaxy.

Image: This is Fig. 1 from the paper. Caption: The maximum allowed travel distance through the interstellar medium (ISM), as a function of (m/A). The blue and red lines are limitations obtained by slow-down due to gas accumulation, and vaporization by dust-collisions, respectively. The plotted results are for a mean ISM proton density of (n) ∼ 1 cm−3. All lines scale as 1/(n). The dashed magenta line is our constraint on ’Oumuamua based on its excess acceleration. The Solar Galactrocentric distance is also indicated. Credit: Bialy & Loeb.

Avi Loeb has recently written about how we might find evidence for extraterrestrial civilizations long gone. From that perspective, he considered the possibility that ‘Oumuamua is just such an artifact, and told me this in an email:

With the perspective of my recent essay in Scientific American, `Oumuamua could be defunct sails floating under the influence of gravity and stellar radiation. Similar to debris from ship wrecks floating in the ocean. The alternative is to imagine that `Oumuamua was on a reconnaissance mission. The reason I contemplate the reconnaissance possibility is that the assumption that `Oumumua followed a random orbit requires the production of ~1015 such objects per star in our galaxy. This abundance is up to a hundred million times more than expected from the Solar System, based on a calculation that we did back in 2009. A surprisingly high overabundance, unless `Oumuamua is a targeted probe on a reconnaissance mission and not a member of a random population of objects.

Loeb also made a comment in his email that ties in to what Breakthrough Starshot is attempting to quantify, a series of missions to the same target — hundreds if not thousands of probes — sent swarm-like to ensure that at least one or a few come close to the world under observation. If something like this were happening with ‘Oumuamua, and given that PAN-STARRS barely detected the object at closest approach, we would not know about any of its fellow probes.

Addendum: Just as I was publishing this I learned of a paper by Eric Mamajek (University of Rochester), who notes that ‘Oumuamua appears to have originated at the Local Standard of Rest (LSR), which is the galactic frame of reference. Quoting Mamajek: “Compared to the LSR, ‘Oumuamua has negligible radial and vertical Galactic motion and its sub-Keplerian circular velocity trails by 11 km s−1.” According to Dr. Loeb in a subsequent email, less than one star in 500 is at that frame of reference to the same precision. (The Mamajek paper, “Kinematics of the Interstellar Vagabond 1I/’Oumuamua (A/2017 U1),” can be found here in preprint form).

It’s an interesting point. If ‘Oumuamua turned out to be artificial, would there be an advantage in such a position? Perhaps so, for as Loeb goes on to say in his email:

I view a sail (like `Oumuamua) floating in interstellar space with stars (like the Sun) running into it as if it were a buoy floating on the ocean surface with boats colliding with it. An artificial origin would naturally place floating sails at the LSR, perhaps as relay stations.

Another item of interest:

Trilling et al., “Spitzer observations of `Oumuamua and `Oumuamua’s density and shape,” as presented at the American Astronomical Society DPS meeting #50, finds no detection of thermal emission from `Oumumua, implying that it must be very reflective or small, which is consistent with the Bialy and Loeb paper. The abstract of the Trilling paper is here.

The Bialy & Loeb paper is “Could Solar Radiation Pressure Explain ‘Oumuamua’s Peculiar Acceleration?” (preprint). The Micheli et al. paper on ‘Oumuamua’s acceleration is “Non-gravitational acceleration in the trajectory of 1I/2017 U1 (‘Oumuamua),” Nature 559 (27 June 2018), 223-226 (abstract).

October 26, 2018

Hayabusa2 Team Looks Toward Sample Collection

With two rovers and a lander already deployed on the asteroid 162173 Ryugu, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) must be basking in the glow of an unusually successful venture. Now we turn to a key part of the Hayabusa2 mission, the retrieval of a surface sample. Two touchdown rehearsals have gone well, providing detailed views of the asteroid’s surface. The plan is to return samples to Earth in December of 2020, but let’s continue to take one thing at a time. Sample retrieval can be dicey, as we saw with the first Hayabusa.

Once known as MUSES-C, the original Hayabusa reached asteroid Itokawa in September of 2005 (I can’t believe it was that long ago — as the cliché would have it, it seems like yesterday). A series of enroute problems included a solar flare that damaged the craft’s solar cells and the failure of attitude-adjusting reaction wheels, while the launch of a probe called MINERVA also failed. Nonetheless, surface particles from Itokawa were successfully returned to Earth.

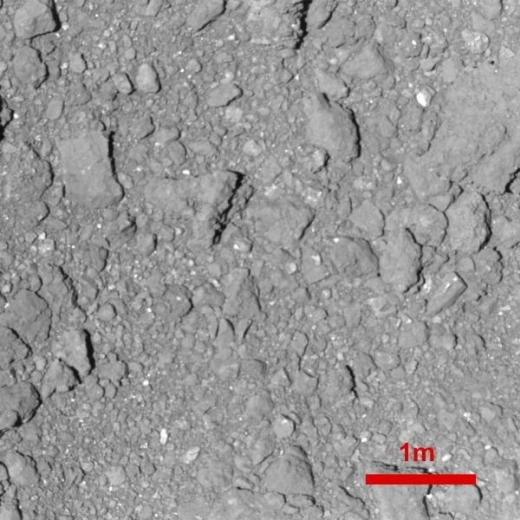

Now the Hayabusa2 team works on landing site selection, no easy task. Keeping the spacecraft safe means looking for regions ideally 100 meters in diameter in which there is an average slope of less than 30 degrees, boulder heights less than 50 centimeters, and an absolute temperature less than 370 Kelvin (97 degrees Celsius). These constraints limit the site to 30 degrees either side of the asteroid’s equator, all this on a diminutive object that presents its own problems.

“Unlike other asteroids we have visited, Ryugu has no powder, no fine-grain regolith. That makes selecting a place to sample more challenging,” said the Planetary Science Institute’s Deborah Domingue. “We are helping characterize the surface to optimize landing site selection.”

Image: This image of asteroid Ryugu was taken with Hayabusa2’s ONC-T (Optical Navigation Camera-Telescopic) on October 15, 2018 from an altitude of 42 meters. The resolution is about 4.6 millimeters per pixel, and this is the highest resolution that Hayabusa2 spacecraft has taken. In fact, this is the highest resolution image that a spacecraft has taken of an asteroid. Credit: JAXA, Tokyo University, Kochi University, Rikkyo University, Nagoya University, Chiba Institute of Technology, Meiji Univeristy, Aizu University, and AIST.

Along with PSI’s Lucille Le Corre, a co-investigator on the mission’s Optical Navigation Camera (ONC) team, Domingue discussed these and other Hayabusa2 operations at a press conference at the 50th annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS) in Knoxville. Hayabusa2 team members present included Masaki Fujimoto, the head of ISAS/JAXA, Hikaru Yabuta, lead of the landing site selection committee and the multi-scale regolith characterization team, Ralf Jaumann, lead for the European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) MASCOT lander, and Eri Tatsumi, the ONC team instrument scientist.

“Since the approach phase began last June, my main goal was to support the Hayabusa2 team in the preparation of touch down operations,” said Le Corre. “In order to assess the sampleability of Ryugu’s terrains I have worked on generating products such as ONC image mosaics and local topographic models. Our data show that the Hayabusa2 team has to carefully select a sampling site to avoid the numerous boulders present on the surface.”

Lacking fine-grained regolith, Ryugu is challenging, and the mission demands a thorough analysis of the surface to ensure a successful sample collection. Three sample collections are planned, the first now likely no sooner than January of 2019. The first two sample collections will use a sampler horn that will catch particles of ejecta raised by the firing of a projectile into the surface. The third sample collection, in the late spring, will collect material dislodged by a kinetic impactor that will produce a crater on the surface of Ryugu.

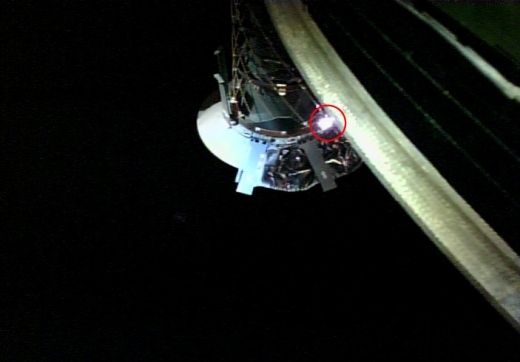

The image below (taken by a camera that, incidentally, was funded by public contributions) comes from the Hayabusa2 website and shows the sampler horn.

Image: Test photograph of the sampler horn taken by the Small Monitor Camera (CAM-H) on April 16, 2018. The shiny part in the red circle is the target plate of the sampler horn which is illuminated by the LRF-S2 laser. If the laser misses this plate, touchdown is in process and bullets will fire to stir up surface material. Credit: JAXA.

The LRF-S2 laser referred to in the caption is a part of planned sample collection activities. In the image, the LRF-S2 laser beam is hitting the tip of the sampler horn, indicating the craft is ready for touchdown operations. During touchdown, the sampler horn will compress as it touches the surface. JAXA describes the operation this way:

When the distance measurement from LRF-S2 changes or the laser from LRF-S2 deviates from its target at the base of the sampler horn, bullets will be fired to stir up the surface material for collection. This makes the LRF-S2 an important device for successful sample collection.

To keep up with Hayabusa2 operations, keep an eye on Twitter @haya2e_jaxa, from which I drew the tweet below.

Dropping down…! Sequential images taken during the approach to Ryugu in our second touchdown rehearsal, TD1-R1-A. https://t.co/sZ9Z8jb6tk pic.twitter.com/wzcG7XcaEX

— HAYABUSA2@JAXA (@haya2e_jaxa) October 26, 2018

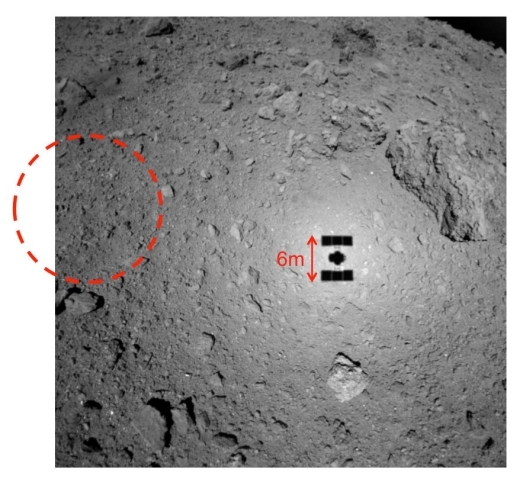

And here is the image with possible touchdown area LO8-B, considered the most promising candidate.

Image: The surface of Ryugu captured with the ONC-W1 at an altitude of about 47m. The image was taken on October 15, 2018 at 22:45 JST. The red circle indicates the candidate point for touchdown, L08-B. Credit: JAXA, University of Tokyo, Kochi University, Rikkyo University, Nagoya University, Chiba Institute of Technology, Meiji University, University of Aizu, AIST).

Paul Gilster's Blog

- Paul Gilster's profile

- 7 followers