Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 99

May 19, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Masturbation Discrimination

From N.Y. trial court judge Lisa Headley in Doe v. Kipp New York, Inc.; the decision was handed down in August, but I just noticed it because an appellate decision earlier this month allowed the case to proceed under a pseudonym:

[P]laintiff commenced this action a year after her employment as a teacher at KIPP middle school and high school was terminated following the dissemination of a video to students depicting plaintiff in a sex act that was saved on her KIPP-issued cellular phone (the "Video"). On June 3, 2022, plaintiff alleges she became aware of the video dissemination, when students brought it to her attention that the video had just been "airdropped" to certain students at KIPP. The plaintiff maintains that the video was taken on personal time and personal property and was potentially accessed and disseminated by students and others, without her consent.

The incident was reported to KIPP administrators, … who investigated the incident. The KIPP administrators determined that the video either may have been disseminated from a KIPP student to whom the plaintiff loaned her phone, or as the plaintiff depicted, that a student airdropped the video to other students. On June 16, 2022, the plaintiff filed a police report regarding the unauthorized access and dissemination of said video, and then on June 24, 2022, the plaintiff was terminated from her employment.

Plaintiff sued alleging many sorts of discrimination, but one in particular seemed a bit unusual:

The Court finds that the plaintiff has stated a legally sufficient fourth cause of action for … Sexual Orientation Discrimination [under New York state law] given that she asserts that she was a member of a protected class as a heterosexual and engaged in self-sexual (auto-erotic) activity, and defendants took adverse action against plaintiff, including terminating her employment, and her lawful expression of her sexuality was a motivating or other causally sufficient factor in defendants' actions….

Among various other claims, the court also allowed a claim to go forward based on New York law banning nonconsensual dissemination of nude or sexual depictions of a person; the law provides,

Any person depicted in a still or video image, regardless of whether or not the original still or video image was consensually obtained, shall have a cause of action against an individual who, for the purpose of harassing, annoying or alarming such person, disseminated, or published, or threatened to disseminate or publish, such still or video image, where such image:

was taken when such person had a reasonable expectation that the image would remain private; and depicts (i) an unclothed or exposed intimate part of such person; or (ii) such person engaging in sexual conduct, as defined in subdivision ten of section 130.00 of the penal law, with another person; and was disseminated or published, or threatened to be disseminated or published, without the consent of such person.

The court reasoned:

[T]he plaintiff argues she sufficiently pled a claim …, given that she was depicted in an intimate video while she was in the act of masturbation; she had a reasonable expectation that this image would remain private; learned through others that several teachers and administrators with no legitimate need to know about the video, much less see the video, either knew about the video or had viewed it; and that their awareness and access could only have been achieved through the defendants' conduct. Plaintiff also alleges that the defendants disseminated the video images without her consent and permission, and beyond the scope necessary to conduct defendants' internal investigation into the matter. Plaintiff alleged the defendants had no "legitimate" purpose for disseminating the video and that their conduct was designed to cause her "harm." …

[The plaintiff also argues that she] pled she was aware that the images were shared beyond any "legitimate business purpose" to other teachers and administrators within the school system…. [T]he Court finds that the plaintiff's Complaint alleges a legally cognizable claim ….

The post Masturbation Discrimination appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Alleged Unindicted Coconspirator in Kickback Scheme Can't Get Name Redacted from Court Opinion

[The person had been a high-level executive in General Electric's African operations.]

From Judge Kevin Castel's opinion Friday in United States v. Da Costa (S.D.N.Y.):

Non-party Leslie Nelson … moves to redact or anonymize all references to him contained in the government's memorandum of law in opposition to defendant's post-trial motions and the Court's Opinion and Order of February 14, 2025 [available here -EV] …. Nelson also seeks an Order requiring the parties to anonymize future references to him in public filings and to seal his own filings in support of this motion…. [T]he Court concludes that the right of public access significantly outweighs the countervailing interests identified by Nelson. His sealing motion will be denied.

Familiarity with the charges against Wilson Da Costa and the underlying proceedings is assumed. On November 18, 2024, a unanimous jury found Da Costa guilty of one count of wire fraud and two counts of aggravated identity theft. On March 16, 2025, the Court sentenced Da Costa principally to a term of 84 months' imprisonment. The charges against Da Costa related to the forgery of certain letter-agreements that were necessary to facilitate the so-called Angola Fast Power Deal. At the time, Da Costa was an executive at General Electric ("GE"), and one witness described him as GE's "leader" in Angola.

Nelson was Da Costa's manager at GE. The Opinion and the government's memorandum of December 20, 2024 summarized some of the trial evidence concerning Nelson. Nelson and Da Costa participated in group text messages with the founder of AEnergia, Ricardo Machado. As recounted in the Opinion, the government submitted evidence that Da Costa and Nelson expected Machado to compensate them with side-payments for their work facilitating the Angola Fast Power Deal. Text messages received into evidence reflected frustration by Da Costa and Nelson that Machado did not pay them more than $5 million each. The Opinion quoted extensively from those messages.

Witnesses referenced Nelson throughout the trial, due in part to his position in GE's corporate hierarchy, his involvement in the Angola Fast Power Deal, and his inclusion in group emails about the underlying transaction. By the Court's count, eight trial witnesses referred to Nelson, and his name or image appeared in numerous trial exhibits. Da Costa also mentioned Nelson by name in his post-arrest interview and an audio recording of Nelson's voice was received into evidence. The Court received into evidence portions of text messages between Da Costa, Nelson and Machado.

Nelson states that friends, acquaintances and business colleagues have questioned him about the references to him contained in the Opinion and the government's post-trial memorandum. Nelson states that he previously had been contacted about his possible interest in seeking a position as a "high-level corporate officer" but that an attorney who conducted a background check on Nelson's behalf recommended that he withdraw due to publicity about this case.

Nelson states that a reporter at a well-known African business publication has asked to interview him. He states that he is "concerned" that the references to him on the public docket will irreparably harm his reputation, damage his business and employment prospects and affect his family members. He urges that he has a strong privacy interest in redacting or anonymizing references to him in filings to the public docket, as well as a due process interest in not being associated with participation in an uncharged crime.

"Judicial documents are subject at common law to a potent and fundamental presumptive right of public access that predates even the U.S. Constitution." "Circuit precedent further establishes that the public's presumptive right of access to judicial records is also independently secured by the First Amendment." … Indeed, "a presumption of openness inheres in the very nature of a criminal trial under our justice system." "[S]uch access is critical as it enables the public to monitor the actions of the courts and juries to ensure 'a measure of accountability' and bolster 'confidence in the administration of justice.'"

Nelson urges that the interests of privacy and due process outweigh any presumption of public access in this case. He principally relies on In re Smith (5th Cir. 1981), which ordered on a writ of mandamus the anonymization of a third party identified as the recipient of bribery payments in the government's written submissions at defendant's plea hearing. Media reports then identified the recipient and his employer refused him certain retirement benefits as a result. The Fifth Circuit concluded that the petitioner's economic and reputational interests had been harmed, and that "no legitimate governmental interest is served by an official public smear of an individual when that individual has not been provided a forum in which to vindicate his rights." "It is equally clear that Petitioner's name was not implicated during either of the District Court's procedural obligations under Rule 11 to determine the factual basis for the defendant's pleas of guilty." The Fifth Circuit characterized the use of the petitioner's name as an "attack" on his "character" and "good name" that did not "afford[ ] him a forum for vindication."

Nearly thirty years later, the Fifth Circuit distinguished Smith in affirming a district court's ruling that denied sealing or redaction of a non-party applicant named in briefing over the admission of out-of-court statements by co-conspirators under United States v. Holy Land Foundation for Relief & Development (5th Cir. 2010). Though the district court concluded that the applicant's due process rights had been violated, it declined to expunge references to the applicant. The Fifth Circuit affirmed, noting that it had never adopted the proposition that a person could not be implicated as a possible co-conspirator in another's criminal case. In the context of briefing about the admissibility of co-conspirator statements, the third-party applicant was identified "in furtherance of a legitimate purpose," supporting the conclusion that the right of public access outweighed the privacy interests of co-conspirators.

Of course, these Fifth Circuit decisions are not binding on this Court, and are afforded persuasive weight. Nelson cites no comparable decisions from the Second Circuit, which has repeatedly emphasized the robust right of public access to judicial documents. "Without monitoring … the public could have no confidence in the conscientiousness, reasonableness, or honesty of judicial proceedings. Such monitoring is not possible without access to testimony and documents that are used in the performance of Article III functions." Public access to a criminal trial has especially significant value.

But even applying the Fifth Circuit's decisions in Smith and Holy Land Foundation, Nelson has not demonstrated a compelling interest that outweighs the presumption of public access. The text exchanges involving Nelson were received into evidence as co-conspirator statements made in furtherance of an uncharged honest services fraud conspiracy and were admitted under Rule 801(d)(2)(E). The Fifth Circuit's Holy Land Foundation decision held that briefing on the admissibility of such statements had a legitimate purpose and that the presumption of public access outweighed the applicant's privacy interests.

Here, the right of public access is even weightier because evidence regarding Nelson was presented to a jury as part of a public trial. The summary of this evidence contained in the government's memorandum and the Opinion were important to the adjudication of Da Costa's post-trial motion brought pursuant to Rules 29 and 33, Fed. R. Crim. P. Nelson's name was used for a legitimate purpose as part of the judicial function, as opposed to the stray references constituting a public smear, as described in Smith. The privacy and due process interests invoked by Nelson do not outweigh the strong right of public access to the full contents of the government's post-trial briefing and the Court's adjudication of Da Costa's motion.

While Nelson has not demonstrated that redaction or anonymization is appropriate, the Court emphasizes that the government brought no charge against Nelson in this case and that the jury's finding of guilt as to Da Costa ought not be understood as a finding of criminal conduct on the part of Nelson.

I asked Mr. Nelson's lawyer for a response, and he wrote:

I think Judge Castel's decision was logical and fair. Notwithstanding that the decision went against Mr. Nelson, the last paragraph of the opinion was a victory for him. The reason I made the motion was that the government's opposition to Da Costa's post-trial motions discussed alleged wrongdoing that Nelson did with Da Costa, and the judge's decision on those motions made it look like he made factual findings as to acts Nelson did that can be considered wrongdoing. I maintained that wasn't fair because Nelson never had an opportunity to contest the facts as he wasn't a party to the case. As a result his reputation will be damaged especially among laypersons who don't know that the factual findings apply only to DaCosta, not Nelson. The judge made that fact crystal clear in the penultimate paragraph:

While Nelson has not demonstrated that redaction or anonymization is appropriate, the Court emphasizes that the government brought no charge against Nelson in this case and that the jury's finding of guilt as to Da Costa ought not be understood as a finding of criminal conduct on the part of Nelson.

If you're interested in Mr. Nelson's side of the anonymization argument, you can see the memorandum supporting the motion; an excerpt:

Public allegations by the government that an unindicted party engaged in criminal wrongdoing implicates due process concerns for that party. As one court observed, "no legitimate governmental interest is served by an official public smear of an individual when that individual has not been provided a forum in which to vindicate his rights." In re Smith (5th Cir. 1981). The Department of Justice recognizes that salient principle and admonishes its prosecutors "to remain sensitive to the privacy and reputation interests of uncharged parties." "In the context of public plea and sentencing proceedings, this means that, in the absence of some significant justification, it is not appropriate to identify (either by name or unnecessarily specific description), or cause a defendant to identify, a party unless that party has been publicly charged with the misconduct at issue."

In this case, before trial, the government identified Mr. Nelson as an unindicted coconspirator, but never by name in public filings. In all pretrial filings, the government scrupulously referred to Mr. Nelson as "GE Employee-1," consistent with the Justice Manual's guidance. At trial, however, the government publicly identified Mr. Nelson as an unindicted coconspirator in order to admit Mr. Nelson's out-of-court statements, including in text messages and emails, at trial. In addressing whether a remedy is warranted for a third party publicly identified as an unindicted coconspirator, courts generally have balanced the interests of the third party against the government's interests. If there is a legitimate government interest in publicly naming the uncharged party, such as at trial for evidentiary purposes, courts generally deny the third party any remedy. Where, as here, the government has no legitimate reason to identify the third party in non-trial public filings, or its interest is outweighed by the third party's privacy and reputational interests, courts have stricken references to the third party.

Given the important governmental interest in proving its case at trial, which includes the admitting co-conspirator statements into evidence under Fed. R. Evid. 801(d)(2)(e), Mr. Nelson does not seek to redact or anonymize his name in trial transcripts or exhibits. Instead, he requests that his name be redacted or anonymized in post-trial filings, including in the Government's Opposition Brief and in the Court's Opinion. The Government's Opposition Brief refers to Mr. Nelson 11 times, each publicly implicating him in specific criminal conduct. The government has no articulable interest in publicly accusing Mr. Nelson of wrongdoing in its post-trial motion papers. Indeed, Mr. Da Costa's post-trial motion papers do not mention Mr. Nelson even once, and none of the government's arguments in its Opposition Brief require specifically mentioning Mr. Nelson's name. Indeed, ten of the eleven references to Mr. Nelson in the Government's Opposition brief appear in the factual background section.

The fact that Mr. Nelson's name has already appeared in trial exhibits or was previously referred to in witness testimony should not affect the analysis here. Republicizing the allegation that Mr. Nelson engaged in criminal wrongdoing, whether in post-trial motions or at sentencing, unwarrantedly causes damage to Mr. Nelson's reputation and impacts his ability to do business, earn a living, and support his family. The newly publicized allegations of Mr. Nelson's wrongdoing can reach new audiences who did not attend or follow the trial. Moreover, there is no explanation in the Government's Opposition Brief that: (i) Mr. Nelson was not charged with any crime; (ii) as a result, Mr. Nelson has no forum to contest or otherwise address the allegations in the Government's Opposition Brief; and (iii) the allegations in that brief are relevant only to the case against Mr. Da Costa and in responding to Mr. Da Costa's motions, but have no legal significance whatsoever as to Mr. Nelson.

The government's specific references to Mr. Nelson in its Opposition Brief resulted in Mr. Nelson being named in the Court's Opinion, which reflects the Court's finding that Mr. Nelson received a $5 million kickback for his involvement in the Angola Fast Power Deal. While this and other findings involving Mr. Nelson in the Court's Opinion concern Mr. Da Costa's motion only, laypersons who review the Court's Opinion likely will not understand that Mr. Nelson: (i) was not charged with the offense; (ii) has no forum in which to contest the government's allegations or the Court's findings; and (iii) the Court's findings have no legal significance whatsoever as to Mr. Nelson.

The Court's Opinion and the Government's Opposition Brief has been disseminated in Mr. Nelson's business circles, and Mr. Nelson's associates and colleagues have expressed concern about the Court's findings and the government's arguments. Furthermore, after reviewing the Court's Opinion and the Government's Opposition Brief, a close friend and advisor of Mr. Nelson recommended that he not pursue a position as a corporate officer because a background investigation by the prospective employer will uncover those documents. In addition, since last week, a reporter has repeatedly contacted Mr. Nelson for comment regarding the references to him in the Court's Opinion and the Government's Opposition Brief. Mr. Nelson is understandably troubled by the potential injury to his reputation from being identified in those documents as having participated in criminal wrongdoing with Da Costa. He fears that any future filings in this case might further besmirch his reputation and adversely impact his business and employment prospects.

Now that the trial is over and the government was able to use Mr. Nelson's statements to prove its case against Mr. Da Costa, the republishing of evidence that Mr. Nelson participated in crimes—without any present government interest in doing so—militates in favor of redacting or anonymizing all references to Mr. Nelson in the post-trial documents that already have been filed, and in the parties' future filings in this case, including sentencing submissions.

The post appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: May 19, 1921

5/19/1921: Chief Justice Edward Douglass White dies.

Chief Justice Edward Douglass White

Chief Justice Edward Douglass WhiteThe post Today in Supreme Court History: May 19, 1921 appeared first on Reason.com.

May 18, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Bigotry, Hypocrisy, and Trump's Admission of Afrikaners as Refugees

[The Administration isn't wrong to admit white South African migrants. But it is wrong to exclude all other refugees, including many fleeing far worse discrimination and oppression.]

Afrikaner migrants arrive in the US. May 12, 2025 (Reuters).

Afrikaner migrants arrive in the US. May 12, 2025 (Reuters).

Last week, the first group of South African white Afrikaners admitted by the Trump Administration as refugees, arrived in the United States. They were admitted under an executive order issued by Trump in February, even as his administration has tried to block all other refugee admissions (a court order has partially restrained the administration's plans in this regard).

In this post, I am going to simultaneously offend many on both right and left by arguing 1) the federal government is right to admit the Afrikaners, 2) the decision to do so while simultaneously barring all other refugees is an instance of incredible hypocrisy and bias by the administration, and 3) if allowed to stand, the admission of the Afrikaners might set some useful precedents for advocates of expanded migration rights; if the Afrikaners qualify for expedited admission as "refugees," so too do a vast range of other people!

Why it is Right to Let Afrikaners Migrate to the US

I have long argued that migration rights should not be restricted based on arbitrary circumstances of ancestry, parentage, place of birth, or race and ethnicity. Afrikaners - and other white South Africans - should not be an exception to that principle.

Some on the left who accept that idea in most other contexts might balk at doing so because of the association of Afrikaners with the evils of apartheid. But it is wrong to ascribe collective guilt to entire racial or ethnic groups. The Chinese government perpetrated the biggest mass murder in the history of world. That does not mean all Mandarin Chinese bear an onus of collective guilt, and Chinese migrants should be barred from the West. Germans don't bear collective guilt for the Holocaust (I say that even though, like most other European Jews, I lost many members of my own family to that atrocity). Russians are not collectively response for Vladimir Putin's atrocities, or those of the communist regime before him. And so on.

Moreover, many of today's white South Africans were either not even born yet when apartheid ended in 1994, or were minors at that time. Such people obviously are not responsible for apartheid-era injustices.

A more plausible justification for excluding white South Africans is the idea that, even if most don't bear personal responsibility for apartheid, they may have horrible racist attitudes, that we should keep out. I would argue the government should not be restricting migration (or any other liberties) based on judgments about people's political views. Speech-based deportations are unconstitutional and unjust, and the same goes for speech-based and viewpoint-based restrictions on migration. If we (rightly) don't trust the government to censor the speech and viewpoints of native-born citizens, the same principle applies to migrants.

Moreover, it is far from clear that most white South Africans today are still virulent racists. The Democratic Alliance - the party supported by most South African whites today (and led by Afrikaner John Steenhuisen) - is a multiracial party that favors racial equality (while opposing affirmative action preferences for blacks).

If some white South African migrants do have awful racial views, we should have confidence in the assimilative power of our own liberal values to mitigate them. In my my book Free to Move: Foot Voting, Migration, and Political Freedom, I describe how most American Muslims (a large majority of whom are immigrants or children thereof) support same-sex marriage, in sharp contrast to the homophobia prevalent in most of the Muslim world. I see a similar pattern among my own immigrant community - those from Russia and other post-Soviet nations. Racism and homophobia are common in their countries of origin, but largely disappear by the second generation among immigrants. Overall, the evidence strongly indicates that home-grown nationalists, not immigrants with illiberal values, are the main threat to liberal democratic institutions in the US and Europe.

There is also a plausible case that white South Africans qualify for refugee status under current law. US law defines a "refugee" as a person who has "a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion." If "persecution" on the basis of race includes racial discrimination by the government, then South African whites plausibly qualify. As my Cato Institute colleague Alex Nowrasteh points out in a piece that is also highly critical of many aspects of the Trump Administration's policy, "The South African government clearly discriminates on the basis of race through its Black Economic Empowerment system and subsequent amended policies with similar-sounding names."

These are affirmative action policies intended to overcome the legacy of apartheid. They are a form of racial discrimination, nonetheless. Elsewhere, I have argued that affirmative action and other "reverse discrimination" policies are not a justifiable answer to our own history of terrible racial discrimination against minorities, and defended the Supreme Court's decision to curb them. Similar reasoning applies to South Africa. South African whites also endure rare, but real, instances of racially motivated violence.

The state-sponsored racial discrimination faced by white South Africans is nowhere near as bad as that endured by blacks under apartheid, or by many oppressed minorities around the world today. But, if "persecution" is defined broadly enough, it might justify allowing them refugee status.

I have advocated broadening the definition of "refugee" to include all forms of persecution and oppression. In that event, the admission of white South Africans would be still easier to defend.

Trump's Policy is Based on Bigotry and Hypocrisy

Though there is a solid case for admitting the Afrikaners, the administration's decision to do so while trying to bar all other refugees is, nonetheless, an example of blatant bigotry and hypocrisy. It is beyond obvious that many refugees and other migrants barred by Trump face far worse oppression and discrimination than that threatening South African whites.

While the South African government discriminates against whites in some ways, it has not engaged in large-scale systematic oppression or mass murder. Despite some Western right-wingers' claims to the contrary, there is no "white genocide" going on there. The government's controversial land confiscation law also falls far short of genocide and only allows uncompensated land seizures in very limited circumstances. The coalition government in power in South Africa right now includes the Democratic Alliance (the party supported by most whites), and even the Freedom Front Plus party (a right-wing party representing primarily Afrikaners).

The fact that only a few dozen Afrikaners have so far taken up Trump's resettlement offer is another indication that their group doesn't face genocide or other genuinely massive violence and oppression. When populations face genuinely massive threats of repression and murder, millions flee, as in the case of the roughly 8 million who have fled Venezuela's oppressive socialist government, and the similar number fleeing Russia's brutal invasion of Ukraine. The Trump Administration, of course, has blocked admission of new Ukrainian and Venezuelan migrants, among others, and is trying to deport many Venezuelans previously admitted to the US.

I won't try to go over them all here. But other examples of refugees fleeing far greater threats of violence and oppression than South African whites are legion.

Thus, it's hard to avoid the conclusion that Trump's policy is based on hypocrisy and bigotry. Relatively modest racial discrimination against a group of whites gets absolute priority over far greater oppression targeting a vast range of other groups. It's not just that South African white Afrikaners get a degree of priority over more severely victimized groups, but the latter are barred from the US refuge program entirely. The government's policy pretty obviously reflects the obsession with white racial grievances prevalent in sectors of the US far right, rather than any objective, racially neutral, standards for allocating refugee admissions.

That conclusion can't be avoided by citing South African whites' relatively high levels of education or other human capital. Lots of high-education people facing persecution and oppression far worse than that endured by are nonetheless excluded from refugee admissions under Trump's policy.

If not for the unusually high deference to executive decisions on immigration policy wrongly granted by the Supreme Court in cases like Trump v. Hawaii, the Trump policy would likely be struck down as an example of blatant racial discrimination. At the very least, the policy is obviously hypocritical and internally inconsistent (unless the consistency is provided by a racist double-standard).

As Bier and Nowrasteh emphasize, this discrimination and hypocrisy are not the fault of the Afrikaner migrants. Don't blame them; blame Trump and his allies.

A Potentially Useful Precedent

Despite the awful motivations underlying it, Trump's bestowal of refugee admissions on Afrikaner South Africans could potentially be a useful precedent for advocates of expanded migration rights.

Nowrasteh notes that the same reasoning that justifies granting refugee status to Afrikaners would also justify extending it to other minority groups victimized by affirmative action policies, such as "Hindu Indians based on their caste, Malaysian citizens who are ethnically Chinese and Indian, people from disfavored regions of Pakistan under the region-based quota system, and other groups in other countries." More generally, it would justify extending refugee status to any group facing comparable or greater racial or ethnic discrimination, anywhere in the world. That includes a vast number of groups with many millions of members.

As Nowrasteh also points out, the Afrikaners were processed and admitted into the United States far faster than all or most previous refugees (within just a few weeks, as opposed to the normal excruciating long wait of about 24 months). If that is acceptable for the Afrikaners, why not for other refugees?

The Trump administration even sent a plane to pick up the first group of Afrikaners at US taxpayer expense. This is in blatant contradiction to right-wing immigration restrictionists' complaints that taxpayer dollars should not be spent on immigrant admissions. They even falsely claim that the Biden Administration spent public funds to fly in CHNV migrants fleeing communist oppression in Latin America, despite the fact that their travel was actually funded by the migrants themselves or by private US sponsors.

With extremely rare exceptions, I think migrant transportation should be funded by the migrants themselves or by private sector organizations. But restrictionists who accept Trump's use of public funds here should not complain about similar expenditures in other cases involving refugees facing far greater oppression.

In sum, there is good reason to open doors to white South African migrants, while also condemning the blatant hypocrisy and bigotry underlying the Trump Administration's policies on this score. If allowed to stand, the admission of the Afrikaners might nonetheless create a useful precedent for future refugee admissions.

UPDATE: Those interested (or those inclined to accuse me of racial double standards on refugees), may wish to check out my 2022 post with links to my long history of writings advocating migration rights for a variety of non-white refugees and other non-white migrants. I would now add my more recent work advocating for Latin American CHNV migrants (most of whom are also not white, at least as that concept is conventionally understood in the US).

The post Bigotry, Hypocrisy, and Trump's Admission of Afrikaners as Refugees appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "AI Hallucination Cases," from Courts All Over the World

From Damien Charlotin, 87 cases so far, mostly from the U.S. but also from Brazil, Canada, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, and the UK. I expect that there are many more out there that didn't make the list (especially since many state trial court decisions don't end up in computer-searchable databases, and I expect the same is true for other countries' courts).

Note that the pace has been increasing: There are more than 22 listed (all but five from U.S. courts) over the last 30 days alone.

The post "AI Hallucination Cases," from Courts All Over the World appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Our Supreme Court Amicus Brief Opposing Termination of CHNV Immigration Parole, Which Would Subject Some 500,000 Legal Immigrants to the Risk of Deportation to Oppressive Regimes

[The brief is on behalf of the Cato Institute and myself. ]

Venezuelans fleeing the socialist regime of Nicolas Maduro. (NA)

Venezuelans fleeing the socialist regime of Nicolas Maduro. (NA)

On Friday, the Cato Institute and I filed a Supreme Court amicus brief in, a case where the Trump Administration is trying to terminate parole status for over 500,000 legal immigrants from four Latin American nations. The brief is available here. Here's a summary of the brief I prepared for the Cato website:

In early 2023, the Department of Homeland Security established a program under which citizens of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela ("CHNV") were eligible to request two years of humanitarian parole into the United States if someone lawfully present in the United States was willing to sponsor them and commit to providing financial and other support. The policy was based on the highly successful Uniting for Ukraine parole program and a more limited parole program for Venezuelan nationals, both of which began in 2022, with the important difference that the number of CHNV parolees was capped at a total of 30,000 per month.

Parole under the CHNV program was granted for two-year terms. In 2025, the new Administration attempted to cut short all of those two-year terms for over 500,000 parolees—giving them only thirty more days of lawful status and associated work authorization. The federal government seeks a stay of a district court order temporarily pausing that termination, which would immediately throw into chaos the lives of half a million people and those connected to them. Termination of parole would render participants vulnerable to deportation to countries wracked by poverty, violence, and horrific oppression by authoritarian socialist governments. A central element of the government's position is the claim that the CHNV program was illegal. Our brief demonstrates that claim is badly mistaken.

In Part I, we show that broad, categorical parole programs have deep historical roots. Since the Eisenhower Administration, the Government has implemented over 125 such categorical programs, involving thousands or even millions of parolees in a single year. Part II explains why the CHNV parole programs are consistent with the statutory requirement that parole be considered on a "case-by-case basis."

In Part III, we demonstrate that migrants from the CHNV countries indeed have "urgent humanitarian reasons" to seek refuge in the United States. They are fleeing a combination of rampant violence, brutal oppression by authoritarian socialist regimes, and severe economic crises. We further show that paroling CHNV migrants also creates a "significant public benefit." That benefit is reducing pressure and disorder on America's southern border. The CHNV program massively reduced cross-border illegal migration by citizens of the nations it covers.

Finally, Part IV shows that, if the Court accepts the Government's position on the legality of the CHNV program, it would also potentially imperil over 100,000 people who received parole under the Uniting for Ukraine program, for people fleeing Russia' brutal invasion of that country. The latter relies on the same legal authority as the former.

This brief is based in part on an earlier amicus brief defending the legality of the CHNV program in Texas v. Department of Homeland Security, a lawsuit filed by twenty GOP-controlled states (that case was eventually dismissed by a conservative Trump-appointed federal judge for lack of standing). I also defended the legality of CHNV in a 2023 article in The Hill, and criticized Trump's attempts to revoke it in a March 2025 post at this site.

The Cato Institute and I are grateful to Grant Martinez, a partner at Yetter Coleman in Houston, TX, for his excellent work in helping adapt my arguments from the earlier brief to this case, at a time when I was extremely busy and could not do this task entirely on my own.

The post Our Supreme Court Amicus Brief Opposing Termination of CHNV Immigration Parole, Which Would Subject Some 500,000 Legal Immigrants to the Risk of Deportation to Oppressive Regimes appeared first on Reason.com.

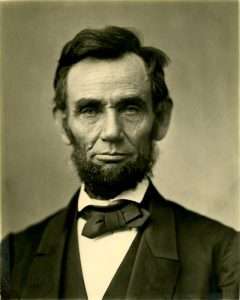

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: May 18, 1860

5/18/1860: Abraham Lincoln wins the Republican Party presidential nomination.

President Abraham Lincoln

President Abraham LincolnThe post Today in Supreme Court History: May 18, 1860 appeared first on Reason.com.

May 17, 2025

[David Post] Nationwide Injunctions and the Rule of Law

[Justice Kagan hits the nail on the head: "nationwide injunctions" are an indispensable tool by which courts rein in unlawful executive action]

At oral argument Thursday in Trump v. Casa, Inc., the "nationwide injunction" case, Justice Kagan put her finger on the question that is, in my view, decisive: If district courts do not have the ability to issue "nationwide injunctions"* against executive misbehavior, i.e., if they are limited to injunctions applicable only to the specific party/ies challenging the government's actions in the cases before them, the courts cannot serve as an effective check on unlawful executive action.

*These injunctions might better be labelled "non-party injunctions" rather than "nationwide injunctions." Listening to the oral argument, it appears that what gives some Justices heartburn with respect to these injunctions is not that they operate "nationwide" (i.e., outside of the geographic district within with the court is authorized to act) but that they purport to affect the rights of non-parties.

Justice Kagan asked the Solicitor General to assume, just for argument's sake, that the Birthright Executive Order is unlawful, on the merits** - that it is an unconstitutional exercise of executive power contravening both the 14th Amendment and a number of Supreme Court precedents (as most of the courts that have looked at it have already concluded).

**This question about the merits - whether the Birthright E.O. is or is not a constitutional exercise of the President's power - was not before the Court at this point, because the government, which was the losing party in the court below, sought SCOTUS review only on the question of whether the court's injunction was valid, not on the underlying merits of the plaintiffs' claim. That turns out to be a rather interesting omission - see below.

If you are uncomfortable making this assumption, because you are convinced that that the Birthright E.O. is not an unconstitutional exercise of presidential power, feel free to craft your own hypothetical here; think of something that a President could do that would be, in your view, clearly and incontrovertibly unlawful: An order requiring, say, the State Department to fire all Jews and African-Americans in its workforce; an order placing the words "Christ is our Savior" on one-dollar bills; an order declaring that ICE can execute warrantless searches whenever it deems them to be in the public interest. Just suppose.***

***Justice Sotomayor used this hypothetical: "A new president orders that because there's so much gun violence going on in the country and he says, 'I have the right to take away the guns from everyone,' and he sends out the military to seize everyone's guns."

Now imagine that Able and Baker and Charlie have been injured by this unconstitutional policy; e.g., each of their citizenships has been revoked, even though they were all born in the United States. They bring suit in federal district court in, say, Houston, arguing that the E.O. is unconstitutional. They win. The court orders the government to reinstate their citizenships.

Nothing remotely controversial or out-of-the-ordinary in the above, and nobody is suggesting otherwise. The Solicitor General acknowledged that it is appropriate for the district court to enjoin the government from imposing its new citizenship policy on Able, Baker, and Charlie, and he conceded that the government would comply with the court's order directing it to reinstate the plaintiffs' citizenships in that case.

But under the Administration's view of things, that is as far as the district court can go:

[From the Administration's Application for a Stay submitted to SCOTUS in this case, available here]

Article III authorizes federal courts to exercise only "judicial Power," which extends only to "Cases" and "Controversies." Under that power, courts can adjudicate "claims of infringement of individual rights," whether "by [the] unlawful action of private persons or by the exertion of unauthorized administrative power." Courts that sustain such claims may grant the challenger appropriate relief—for instance, an injunction preventing the enforcement of a challenged law or policy against that individual—but cannot grant relief to strangers to the litigation. Article III does not empower federal courts to "exercise general legal oversight of the Legislative and Executive Branches." To reach beyond the litigants and to enjoin the Executive Branch's actions toward third parties "would be not to decide a judicial controversy, but to assume a position of authority over the governmental acts of another and co-equal department, an authority which plainly [courts] do not possess."

Only the Supreme Court, the Administration asserts, can declare the policy unconstitutional as to persons who are not party to any lawsuit, and only the Supreme Court can enjoin the government from revoking the citizenship of persons similarly-situated to Able, Baker, and Charlie but located in other judicial districts.

It's not a totally unreasonable position: only the Supreme Court has truly nationwide jurisdiction, and it alone should be permitted to decide "the law of the land," not some district court in Texas or Massachusetts or Colorado.

But Justice Kagan identified the fatal flaw in the argument:

If [the government] wins this challenge and we say that there is no nationwide injunction and it all has to be through individual cases, then I can't see how an individual who is not being treated equivalently to the individual who brought the case would have any ability to bring the substantive question to us…. In a case like this, the government has no incentive to bring this case to the Supreme Court because it's not really losing anything. It's losing a lot of individual cases, which still allow it to enforce its EO against the vast majority of people to whom it applies. . . . I'm suggesting that in a case in which the government is losing constantly, there's nobody else who's going to appeal; they're all winning! It's up to you, [the government], to decide whether to take this case to us. If I were in your shoes, there is no way I'd approach the Supreme Court with this case.

Which is exactly what happened here! As I noted above, the government didn't ask the Court to review the adverse determination that the E.O. was "blatantly unconstitutional." Why not, you ask? Because it knows full well that it is almost certain to lose when that question comes to the Court, at which point the government would have to openly defy "the law of the land" if it wanted the State Department and DHS and ICE and the other executive agencies to operate under its new definition of citizenship. Instead, if it could just get rid of these pesky "non-party injunctions," it would be perfectly content to just go on losing, one case and one plaintiff at a time, forgoing its right to appeal all the adverse decisions, while work to implement the E.O. with respect to the millions of people who are not parties to the various lawsuits goes on apace.

And paradoxically enough, the more egregious the executive's conduct - the more obviously and incontrovertibly unconstitutional it is - the more likely it is that it will lose every case, which will mean that the question of its constitutionality never gets to the Supreme Court for a conclusive ruling.

Clever, no? Another seam, or fault-line, in the web of constitutional protections and the separation of powers has been exposed.

I regard this as a fatal objection to a rule prohibiting non-party injunctions in all cases because it fails what we might call the Hitler Test: if we are ever so unfortunate as to have a president who wanted to do Hitler-ian things, would this rule help to prevent that from happening or not? It's not a terribly high bar, but a rule prohibiting non-party injunctions in all cases doesn't make it over. I think that a majority of the Court will at least be a little troubled by a rule that incorporates this perverse legal incentive to act in an outrageously unconstitutional manner. Though I'm loathe to predict the direction the Court might go on this issue, it doesn't appear to me that there is majority support for a blanket prohibition on non-party injunctions, and I think it more likely that the Court will find some intermediate position that will spell out the conditions under which non-party injunctions are permissible and within the discretion of the district courts. We'll see if I'm right about that.

The post Nationwide Injunctions and the Rule of Law appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: May 17, 1954

5/17/1954: Brown v. Board of Education and Bolling v. Sharpe are decided.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: May 17, 1954 appeared first on Reason.com.

May 16, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Supreme Court Issues Ruling Temporarily Blocking Alien Enemies Act Deportations

[The ruling held that migrants detained under AEA had not been given adequate notice of their potential deportation. It also reflects the Court's growing distrust of the Trump Administration.]

(Joe Ravi / Dreamstime)

(Joe Ravi / Dreamstime) Today, in AARP v. Trump, the Supreme Court issued a ruling blocking deportation of a group of Venezuelan migrants the Trump Administration had been trying to use the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 deport to imprisonment in El Salvador. The AEA allows detention and deportation of foreign citizens of relevant states (including legal immigrants, as well as illegal ones) "[w]henever there is a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion is perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States by any foreign nation or government."

The Supreme Court's latest ruling doesn't address the issue of whether the administration's invocation of the AEA is legal, though multiple lower courts have ruled it is not, because there is no war, "invasion," or "predatory incursion" going on (only one badly flawed ruling goes the other way on "predatory incursion"). Instead, a 7-2 majority holds only that Venezuelan detainees slated for deportation under the AEA in the Northern District of Texas are entitled to a temporary injunction blocking deportation, because they were not granted adequate notice:

[I]n J. G. G. [the Court's first ruling on Trump AEA deportations], this Court explained—with all nine Justices agreeing—that "AEA detainees must receive notice . . . that they are subject to removal under the Act . . . within a reasonable time and in such a manner as will allow them to actually seek habeas relief " before removal. 604 U. S., at ____ (slip op., at 3). In order to "actually seek habeas relief," a detainee must have sufficient time and information to reasonably be able to contact counsel, file a petition, and pursue appropriate relief. The Government does not contest before this Court the applicants' description of the notice afforded to AEA detainees in the Northern District of Texas, nor the assertion that the Government was poised to carry out removals imminently. The Government has represented elsewhere that it is unable to provide for the return of an individual deported in error to a prison in El Salvador, see Abrego Garcia v. Noem, No. 25−cv−951 (D Md.), ECF Docs. 74, 77, where it is alleged that detainees face indefinite detention, see Application for Injunction 11. The detainees' interests at stake are accordingly particularly weighty. Under these circumstances, notice roughly 24 hours before removal, devoid of information about how to exercise due process rights to contest that removal, surely does not pass muster. But it is not optimal for this Court, far removed from the circumstances on the ground, to determine in the first instance the precise process necessary to satisfy the Constitution in this case. We remand the case to the Fifth Circuit for that purpose.

To be clear, we decide today only that the detainees are entitled to more notice than was given on April 18, and we grant temporary injunctive relief to preserve our jurisdiction while the question of what notice is due is adjudicated.

In a highly unusual earlier ruling in this same case, the Supreme Court literally issued an order blocking deportation in the middle of the night. The per curiam majority opinion in today's ruling recounts the circumstances of that previous episode, and its relevance to the current decision. The combination of that earlier ruling and today's decision reflects the majority's growing distrust of the Trump Administration's handling of AEA - and perhaps other - deportations. Note the reference to the Administration's refusal to return an illegally deported migrant in the Abrego Garcia case.

I could be wrong, and my record as a Supreme Court prognosticator is far from perfect. But I think when the Court does review the Administration's use of the AEA more fully, they are unlikely to be deferential. In a concurring opinion, Justice Kavanaugh argues the Court should immediately move to resolve the broader issues at stake, in this very case. All or most of the other justices must have disagreed. But it seems likely these issues will return to the Court sooner or later.

In a forceful dissent joined by Clarence Thomas, Justice Samuel Alito disputes the majority's characterization of the facts (contending, among other things, that deportation wasn't really imminent) and argues the Supreme Court lacked jurisdiction to consider the case at this time. I will not go into these points in detail. But I think the majority's account is more persuasive, and also that the Administration does not deserve the benefit of the doubt in such matters, given their earlier shenanigans in Abrego Garcia, and at least one of the AEA cases.

Justice Alito also argues that class action certification is inappropriate in a habeas case, like this one. I will leave that issue to habeas and class action experts, except to note that multiple lower courts have certified habeas classes in AEA cases, and doing so may be the only way to ensure meaningful due process for detained migrants threatened with deportation.

For the moment, as Georgetown Prof. Steve Vladeck notes,"[b]ecause lower courts have blocked use of the act in every other district in which the president has sought to invoke it, that means it's effectively pausing all removals under the act until the 5th Circuit – and, presumably, the Supreme Court itself – conclusively resolves whether they're legal and how much process is due if so." The legal battle over Trump's invocation of the AEA will surely continue, and I will have more to say about it in due time.

The post Supreme Court Issues Ruling Temporarily Blocking Alien Enemies Act Deportations appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers