Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 267

September 12, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Thursday Open Thread

[What's on Your Mind?]

The post Thursday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

September 11, 2024

[David Kopel] Malcolm Gladwell's Invented Facts Make Good Stories

[His "Revisionist History" podcast can amount to historical fiction]

Being the son of two lawyers, I encountered cultural differences when I married into an Irish-American family. My new relatives were excellent story-tellers, and to them, the quality of the story was independent of its literal veracity. After a few years, I learned that when my wife is telling a story, even a story which I was a character, I should not interrupt her to correct any detail. The factual accuracy of any given detail was much less important — in fact, unimportant — compared to what the detail could contribute to an interesting yarn. So too with Malcolm Gladwell, host of the Revisionist History podcast. His tales are well-told; just don't confuse his revised narrations with actual history.

A case in point is the first episode of his 2023 gun control series, The Sudden Celebrity of Sir John Knight. To see how he revises facts to improve a story, consider a tale of his that makes me look better than in real life.

In 1686, Sir John Knight, of Bristol, England, was charged with violating the 1328 Statute of Northampton. The statute forbade the English "to go nor ride armed by night nor by day" under listed circumstances. According to the indictment, Knight "did walk about the streets armed with guns, and that he went into church of St. Michael, in Bristol, in the time of divine service, with a gun, to terrify the King's subjects."

Knight was acquitted by the jury. The presiding judge was the Chief Justice of King's Bench. His statements on the legal interpretation of the Statute of Northampton were reported by two reporters. Sir John Knight's Case, 87 Eng. Rep. 75, 3 Modern Rep. 117 (K.B. 1686); Rex v. Sir John Knight, 90 Eng. Rep. 330; Comberbach 38 (K.B. 1686).

How did this 1686 case become known to Americans? First, it was cited in William Hawkins' famous criminal law treatise, A Treatise of the Pleas of the Crown (1716, with 8 editions through 1824), for Hawkins' explanation of when carrying arms is and is not legal. The Hawkins treatise is tied for first as the most-owned imported criminal law book in colonial American law libraries. Herbert A. Johnson, Imported Eighteenth-Century Law Treatises in American Libraries 1700-1799 (1978). (Matthew Hale's The History of the Pleas of the Crown tied Hawkins for first.)

Hawkins' point that carrying arms is generally legal was cited by two American Justice of the Peace Manuals around the time of the Second Amendment. William Waller Hening, The New Virginia Justice 17-18 (1795); James Parker, Conductor Generalis; Or the Office, Duty and Authority of Justices of the Peace 11 (1st ed. 1764).

Besides the Hawkins treatise, another way that Knight's case likely became known was via George Wythe, of William and Mary. He was the first American law professor, and his large library included volume 3 of Modern Reports, and Comberbach, both of which reported the Knight case. Here is what Gladwell says:

David Kopel, once combed through the library of an 18th century law professor named George Wythe, who taught law to a supreme court justice, a couple of presidents, some founding fathers, and he found that John Knight's name was all over law books back then.

The part about Wythe is true. He did teach the law to John Marshall, Thomas Jefferson, and many other Founders. The rest is false.

I have never been on the campus of William and Mary. The closest I ever came was chaperoning a school field trip at Colonial Williamsburg. If I had gone to the William and Mary campus, I could not have "combed through" Wythe's library, because it no longer exists. Wythe gave his library to Thomas Jefferson, who later donated it to the Library of Congress, which the British burned on August 19, 1814, during the War of 1812.

Because neither I nor any man alive have ever seen any of the physical books in Wythe's library, I never said that Wythe's library shows that "John Knight name was all over law books back then." To the contrary, Knight's name isn't even mentioned in the Hawkins treatise; rather, Hawkins just cites "3 Mod. 117, 118" as part of his support for the statement "That no Wearing of Arms is within the Meaning of the Statute [of Northampton] unless it be accompanied by such Circumstances as are apt to terrify the People . . . " 1 Hawkins at ch. 63, page 136.

What I actually did was spend a few minutes William & Mary Law Library's website, Wythepedia: The George Wythe Encyclopedia, which catalogues all the books of Wythe's library. Finding out that Wythe owned the Hawkins book and the two reporters who covered the John Knight case took me just a few minutes. (Here are the William and Mary Library cites for Wythe's ownership of Hawkins, 3 Modern Reports, and Comberbach.)

Gladwell's invention of the library tale makes for better story-telling. It exaggerates the importance of Gladwell's own story about John Knight, with his name "all over the law books back then." Likewise, the invented story about me having "combed" through Wythe's library is more interesting than the actual facts of my doing a few minutes of Internet research into an online catalog for a library that ceased to exist over two centuries ago.

To further heighten the drama of Gladwell's historical fiction, he names me "a founding member of the John Knight fan club." According to Gladwell, I consider Knight "the man whose brave example saved America from the tyranny of restrictive gun laws."

Actually, I have never written a single good word about Sir John Knight. My longest treatment of Knight's Case is in my coauthored textbook Firearms Law and the Second Amendment, chapter 22, pages 2100-02. There, I pointed out that Knight, "loved to use the law to persecute non-Anglicans" — namely Catholics, and also Protestants who did not adhere to the Church of England.

Perhaps Gladwell invented the claim that I supposedly extol John Knight because when I was in England on vacation, I visited the scene of the alleged crime that led to Knight's famous trial: St. Michael's Church in Bristol. I also looked at the gravestones, to see if Knight was buried there, but they were too worn for legibility. While I sometimes visit famous crime scenes, the visits do not indicate that I consider anyone involved to be heroic.

Near the end of the episode, Gladwell provides the moral, via historian Tim Harris, who says Knight was "nasty," "vindictive and spiteful," "a bigot," "a troublemaker." "I would hardly say that he was the sort of hero figure that champions of American liberty would want to celebrate."

Very true, and contrary to Gladwell's claim, no American has ever "celebrate[d]" John Knight. What some Americans, including me, have done is accurately describe the legal case. A person who accurately describes Miranda v. Arizona (1966) (6th Amendment self-incrimination) or Roper v. Simmons (2005) (8th Amendment cruel and unusual punishment) is not being a "fan" of Ernesto Miranda or Matthew Simmons. Miranda and Simmons were bad people. Even so, their cases set important limits on state power. To cheer the results in the Miranda or Simmons cases is not to "celebrate" either defendant.

Gladwell's concoction of Americans who celebrate Sir Knight is part of a larger fiction. He claims that the U.S. Supreme Court's 2022 New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen pivoted on Knight's case. That case involved the Second Amendment right to bear arms.

According to Gladwell:

You want to play early history? I give you a crucial law from 1328, which absolutely the founders knew about that restricts guns WAY MORE than anything we're talking about in this court, your honor. If court cases are chess, this is check. The only way the gun rights crowd can win is if they can find their own bit of ancient history that trumps the Statute of Northampton, and incredibly, they do.

Then:

Everyone thinks that English common law, on which the American legal tradition is based, was hostile to people walking around with guns, but that is not true. John Knight was acquitted. John Knight goes up against the Statute of Northampton and John Knight wins. One side says, "The Statute of Northampton, check." The other side counters, "John Knight, checkmate."

The check/checkmate line is clever storytelling, but it's a figment of Gladwell's active imagination.

Regarding Gladwell's claim that "Everyone thinks that English law . . . was hostile to people walking around with guns." In 1689, the English Bill of Rights was enacted. It declared: "That the Subjects which are Protestants, may have Arms for their Defence suitable to their Conditions, and as allowed by Law." From then until 1870, when a tax was imposed on public handgun carry, no English law restricted an individual peaceably carrying a gun for lawful self-defense, and there are no known cases of any such prosecution.

In Knight's case, the Chief Justice said that the Statute of Northampton had "almost gone in desuetude." That is, it had been unenforced for so long that it had almost become legally unenforceable. But the Chief Justice saved the statute, for he said that it simply reflected a longstanding principle of common law: carrying a weapon is unlawful when done in malo animo — with bad intent. The few post-1686 prosecutions under the Statute of Northampton all involved persons who were behaving dangerously with arms. E.g. Rex v. Dewhurst, 1 State Trials, N.S. 529, 601-02 (1820) ("A man has a clear right to protect himself when he is going singly or in a small party upon the road where he is travelling or going for the ordinary purposes of business. But I have no difficulty in saying you have no right to carry arms to a public meeting, if the number of arms which are so carried are calculated to produce terror and alarm. . . .") (discussing constitutionality of a temporary law against arms carrying by rebels in six counties); Rex v. Meade, 19 L. Times Rep. 540, 541 (1903) (a man shot a pistol through a neighbor's window because of a dispute over a woman; the public should "know that people could not fire revolvers in the public streets with impunity."). See also Kopel et al., Firearms Law at 2103-07 (post-1686 history of Statute of Northampton in English law).

As for the Bruen case, nothing in English history was ever "check" or "checkmate." The core of the Bruen decision is the original public meaning of the Second Amendment, when it was ratified by the American people in 1791. The opinion of the Court is 63 pages in U.S. Reports. The Statute of Northampton is discussed in two pages (starting on the second half of page 31), and Knight's case gets one long paragraph. The Statute of Northampton reappears for one sentence on page 36.

Although Gladwell says that originalism is to "play early history," a 1328 English statute and a failed 1686 English prosecution are not "check" or "checkmate" for discerning American original public meaning in 1791; the laws of America in the immediately preceding and following decades are much more relevant, said the Court. Colonial laws are covered in pages 37-42 of the Bruen opinion. American laws between 1791 and the beginning of the Civil War are pages 42-51. These are the core of Bruen's historical analysis. Gladwell's notion of "check" in 1328 England and "checkmate" in 1686 make for an entertaining podcast, but not for accurate legal history.

Relying on Malcolm Gladwell's Revisionist History podcast for actual history is like relying on Comedy Central to understand current events. If you already know the relevant history or news, then the programs are entertaining, but not to be taken seriously. I haven't fact-checked all of Malcolm Gladwell's work, but I do know that a story-teller who announces that a person was in a place he has never been (me, on the William & Mary campus) combing through a library collection that has not existed for over two centuries (George Wythe's personal collection), the story-teller's prime objective is not accuracy.

The post Malcolm Gladwell's Invented Facts Make Good Stories appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Frederick Douglass Praises the "Courage" Of Justice John Marshall Harlan

[“In these easy going days [Harlan] should find himself possessed of the courage to resist the temptation to go with the multitude”]

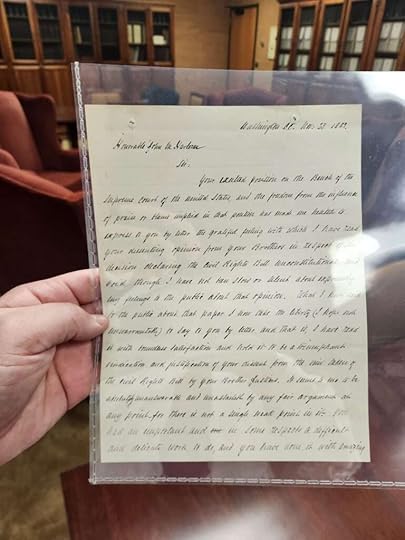

On Tuesday, I spoke at the Louisville Federalist Society Chapter about presidential immunity. After the debate, I was fortunate enough to visit the Library's special collections. The collection includes papers from Justice Louis Brandeis, the namesake of the law school, who is actually buried outside the building. The collection also includes papers from Justice John Marshall Harlan I. I have spent some time with Justice Harlan's papers at the Library of Congress. In 2013, I published a paper with Brian Frye and Michael McCloskey that transcribed Harlan's constitutional law lecture notes. (To this day, I use some of Harlan's lines in class–for example, when I tell my students that the Supremacy Clause is the most important provision in the Constitution; without it, everything else would fall apart.) Over the years, I've corresponded with Peter Scott Campbell, a librarian at Louisville. Campbell was kind enough to show me around the room.

One of the coolest pieces I saw was a letter that Frederick Douglass wrote to Justice Harlan shortly after the Civil Rights Cases (1883) was decided. I encourage you to read the entire letter, which Campbell helpfully transcribed. Here is an excerpt:

[Harlan's dissent] seems to me to be absolutely unanswerable and unassailable by any fair argument at any point for there is not a single weak point in it. You had an important and in some respects a difficult and delicate work to do, and you have done it with amazing ability skill and effect. . . . I have nothing bitter to say of your Brothers on the Supreme Bench, though I am amazed and distressed by what they have done. How they could at this day and in view of the past commit themselves and the country to such a surrender of National dignity and duty, I am unable to explain. I have read what they have said, and find no solid ground in it. Superficial and [???], smooth and logical within the narrow circumference beyond which they do not venture, that is all.

To this day, I remain convinced that Justice Harlan was correct in the Civil Rights Cases. Had his view prevailed, the Court would have never needed to contort the Commerce Clause is Katzenbach and Heart of Atlanta Motel. And cases like United States v. Morrison would have come out differently. Moreover, if the Civil Rights Act of 1875 had been upheld, we never would have had Plessy, because a segregation law on a public conveyance would have been preempted by the federal bill. Everyone focuses on Plessy, but truly the root cause of the problem was The Civil Rights Cases, and if you want to go back a decade earlier, The Slaughter-House Cases.

Douglass also included an article he wrote in The American Reformer newspaper about Harlan's dissent. The first paragraph defends Harlan's decision on its own terms:

[Harlan] has felt himself called upon to isolate himself from his brothers on the Supreme Bench, and to place himself before the country as the true expounder of the Constitution as amended, and of the duty of the National Government to protect and defend the rights of citizens against any infringement of their liberty. The opinion which he has given to the country, as to the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Bill, places his name among the ablest jurists who have occupied the Supreme Court. No utterance from that Bench, since the celebrated and splendid opinion given by Judge Curtis against Judge Taney's infamous Dred Scott decision, has equaled this opinion in ability, thoroughness, comprehensiveness and conclusive reasoning. Compared with it the decision of the eight judges was an egg shell to a cannon ball. We are told in Scripture that one shall chase a thousand, but one opinion like this could put to flight ten thousand of such decisions as the thin, gaunt and hungry one which denies the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Bill, and the duty of the Federal Government to protect the rights and liberties of its own citizens. No man, unless blinded by passion, prejudice, or selfishness, can read this opinion without respect and admiration for the man behind it. Where the decision of the Court is narrow, superficial and technical, the opinion of Judge Harlan is broad and generous, and grapples with substance rather than shadow, with things as they are rather than with abstractions…

A few important points jump out here. First, Douglass twice refers to the Civil Rights Act of 1875 as "protecting the rights and liberties" of citizens. This is precisely the correct accounting of the Fourteenth Amendment. Section 1 made the freedmen citizens, and granted them the privileges and immunities of citizenship. The states then had a duty to equally protect those privileges and immunities, which included the right to access places of public accommodation. And Congress, through Section 5, could enact appropriate legislation to ensure those rights were protected. The Equal Protection Clause was not, as the Warren Court would tell you, about treating everyone equally. Instead, Douglass's conception is how Chris Green explains it: the Equal Protection Clause imposes a duty to protect everyone equally from the violation of rights. Douglass was able to articulate sophisticated constitutional principles in so few words.

Second, Douglass pays homage to Justice Curtis's dissent in Dred Scott. It is not well known, but Curtis resigned from the Supreme Court shortly after Chief Justice Taney's decision. Curtis was held in high esteem by Douglass, and Harlan entered that pantheon. I would wager that Justice Story, author of Prigg v. Pennsylvania, would not make the cut.

Third, Douglass uses the phrase "grapples with substance rather than shadow." This phrase may sound familiar. Chief Justice Roberts used the same phrase in the Trump immunity decision:

That proposal threatens to eviscerate the immunity we have recognized. It would permit a prosecutor to do indirectly what he cannot do directly—invite the jury to examine acts for which a President is immune from prosecution to nonetheless prove his liability on any charge. But "[t]he Constitution deals with substance, not shadows." Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. 277, 325 (1867).

Another passage from Douglass is particularly significant in light of recent discussions on this blog:

As to Justice M. Harlan, no man in America at this moment occupies a more enviable position. His attitude is one of marked moral sublimity. The marvel is that, born in a slave State, as he was, and accustomed to see the colored man degraded, oppressed and enslaved, and the white man exalted; surrounded by the peculiar moral vapor inseparable from the slave system, he should so clearly comprehend the lessons of the late war and the principles of reconstruction, and, above all, that in these easy going days he should find himself possessed of the courage to resist the temptation to go with the multitude. He has chosen to discharge a difficult and delicate duty, and he has done it with great fidelity, skill and effect. In other days, when Garrison, Phillips, Sumner, Wilson and others spoke, wrote and moved among men, Old Massachusetts did not leave to Kentucky the honor of supplying the Supreme Bench with a moral hero. That State then spoke through the cultivated and legal mind of Judge Curtis. Happily for us, however, Kentucky has not only supplied the needed strength and courage to stem the current of pro-slavery reaction, but she has also supplied in Justice Harlan patience, wisdom, industry and legal ability, as well as heroic courage.

I've written at some length about the concept of judicial courage. And I cite a lack of courage to explain why some judges vote the way they do. Will, Orin, and Sam recoil at my discussion of judicial "courage." They think it is a corrosive and dangerous way of thinking about judges. They also think it problematic to focus on how a judge votes, rather than substance of their opinions.

This latter point would come as a surprise to entire political science departments that painstakingly count how Justices vote. And I assure you, my "courage" analysis is not new. It goes at least back to Douglass, and really much earlier. Judges today, judges in the twentieth century, and judges in the nineteenth century, are not much different. There is always the "temptation" to, as Douglass writes, "go with the multitude." Now you might try to localize "courage" to standing up to racism and Jim Crow. But that was not Douglass's argument at all. Rather, courage means a willingness to stand alone for your principles, and to go out on your own. Lone dissents take courage. Justice Thomas issues them without any concern. Justice Alito has issued a few over time. Justice Scalia's Morrison dissent comes to mind. How often are the other Justices willing to stand alone, and buck the trend of the "multitudes"?

On a related point, I have some other archival documents from Justice Brennan's papers in which he thanks and praises a Supreme Court advocate, who is still with us, for his defense of the Court. I'll publish those at the appropriate time. There is nothing new under the sun.

The post Frederick Douglass Praises the "Courage" Of Justice John Marshall Harlan appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Attempt to Entirely Seal Title IX Complaint on Privacy Grounds Rejected

From Judge Dale Ho's decision today in Doe v. Columbia Univ. (S.D.N.Y.):

[T]hese cases concern allegations of sexual assault and that the events in question occurred from 2012 to 2014 or 2015, around the time that Plaintiff was an undergraduate student at Columbia University…. Plaintiff … filed identical letters seeking to proceed pseudonymously in each case …. In his letter motions seeking pseudonymous status, Plaintiff noted that his "Complaint includes sensitive health information regarding a sexual assault, and medical and psychiatric treatment for these assaults, which could have deleterious consequences if this information became public record." Plaintiff did not request that the Complaints be sealed altogether, but the Clerk of Court, as a precaution given Plaintiff's motions to proceed under a pseudonym, limited electronic docket access to Plaintiffs' Complaints to "court users and case participants."…

I moved to intervene and unseal the Complaint "with any necessary redactions of various people's personally identifying information" (but didn't oppose pseudonymity), and the court agreed; an excerpt:

First, there is no doubt that complaints are judicial documents. "A complaint, which initiates judicial proceedings, is the cornerstone of every case, the very architecture of the lawsuit, and access to the complaint is almost always necessary if the public is to understand a court's decision."

Second, a strong presumption of public access attaches to complaints. "Complaints have historically been accessible by default, even when they contain arguably sensitive information" and "public access to the complaint and other pleadings has a significant positive role … in the functioning of the judicial process." Under common law, because complaints are "highly relevant to the exercise of Article III judicial power," "the presumption of access is at its zenith."

Third, the Court … agrees that there are important countervailing privacy interests identified by Plaintiff, but concludes that these concerns can be accommodated via pseudonymity rather than through complete sealing of the Complaints. Indeed, Plaintiff publicly filed his Complaints and did not affirmatively request sealing of them, but rather sought only pseudonymity to protect his privacy interests. It was only in an abundance of caution that the Court, following a decision in the previous case brought by the Plaintiff, Doe I, ordered sua sponte that the Complaints be sealed. But the Second Circuit and district courts within it have generally addressed the type of serious privacy concerns raised by the Plaintiff by permitting pseudonymity and other limited redactions to protect personal information, while otherwise leaving the relevant judicial documents publicly available in redacted form….

Nevertheless, Plaintiff—despite having affirmatively sought only pseudonymity and not complete sealing of the Complaints—now argues that pseudonymity is insufficient to protect his interests, because (1) "[u]nsealing the complaints detailing my abuse would likely trigger a relapse of [my] symptoms and retraumatize me all over again"; and (2) even with pseudonymity, unsealing the details "of these allegations themselves could lead to the identification of plaintiff."

The Court takes concerns of this nature seriously. But they are difficult to credit in this dispute, in light of the fact that Plaintiff himself has made his allegations publicly on numerous occasions: as noted, Plaintiff filed the Complaints publicly and did not request that they be sealed, and he has publicly filed multiple other documents describing his allegations—such as his Intervention Opposition and his Opposition to Sua Sponte dismissal—and as noted, he opposes redactions to those documents. {In his August 16 Letter, Plaintiff also threatened to "shar[e] my story with media" if the Court did not reconsider, inter alia, its previous decision allowing Columbia to redact the Oppositions.}

More fundamentally, Plaintiff cites no legal authority supporting the proposition that redactions to protect pseudonymity are insufficient, and that complete sealing of the Complaints is necessary. Plaintiff cites several cases, but each of these cases considered only the issue of pseudonymity and not the complete sealing of the relevant judicial documents—and several of the cases did not even grant pseudonymous status.

Perhaps the best case for Plaintiff is Doe v. Town of Lisbon (1st Cir. 2023), in which the First Circuit affirmed a district court's decision denying a similar motion by Volokh.

But there, the First Circuit made clear that Town of Lisbon was not a "sealing/unsealing case," as a version of the complaint in that case was available on the public docket, with only the Doe plaintiff's name redacted, such that "the public ha[d] full access to all information contained in the docket other than one party's name." Volokh's motion in that case was denied because it sought to pierce pseudonymity, which his motion in this case does not.

In light of the discussion above, the Court concludes that continued sealing of the Sealed Complaints is inappropriate. Volokh's motion to unseal the Complaints is therefore GRANTED, but only IN PART. The Court agrees that some redactions may remain appropriate to address privacy and confidentiality concerns. But such redactions must be "narrowly tailored" to protect the privacy interests of the Plaintiff and non-parties. They may include "alleged victims' names and identifying information that could allow a reasonable person who does not have personal knowledge of the relevant circumstances to identify with reasonable certainty [these] individuals."

The court also notes some seemingly spurious citations and quotes in plaintiff's papers:

Plaintiff cites Doe v. Townes, and purports to quote it as follows:

Redacting my name would be insufficient to protect my privacy, as "the public filing of a complaint containing detailed allegations of sexual assault, even with names redacted, can still lead to exposure of the plaintiff's identity."

The Court cannot locate this purported quotation in Townes, which as noted, recommended denying pseudonymous status. Nor can the Court locate this quotation in the other cases cited by Plaintiff, or in any case at all on Westlaw or LEXIS. {This is troubling, and is not the only instance of Plaintiff offering quotations or summaries of cases that appear to be inaccurate or non-existent. Cf. Mata v. Avianca, Inc. (S.D.N.Y. 2023) ("Many harms flow from the submission of fake opinions."). In light of Plaintiff's pro se status, however, the Court will not impose sanctions at this time.} …

Plaintiff also states that he did not become aware of his claims in the Kachalia case until sometime "after the 2023 settlement," Pl. Opp'n to Sua Sponte Dismissal 5, citing a case identified as "2022 WL 2917890" which purports to indicate that the ASA [the New York Adult Survivors Act] revives otherwise time-barred claims where delay is attributable to repressed memories. See id. at 6 ("See Doe, 2022 WL 2917890, at *5 (ASA revives claims that were not previously brought due to repressed memory of abuse)"); id. at 12 ("See Doe, 2022 WL 2917890, at *5 (ASA revives claims that were not previously brought due to repressed memory of abuse)"). This point is irrelevant because, as noted supra, the ASA does not revive federal claims. The Court notes, however, that there is no case on Westlaw that the Court can identify with the citation "2022 WL 2917890." Plaintiff's short citation is apparently in reference to a case he fully cites as "Doe v. Poly Prep Country Day Sch., No. 20 Civ. 3628, 2022 WL 2917890 (E.D.N.Y. July 25, 2022)." While the Court was able to identify a similarly captioned case from the same year, Doe v. Poly Prep Country Day Sch., No. 20 Civ. 4718, 2022 WL 4586237, at *1 (E.D.N.Y. Sept. 29, 2022), that case makes no reference to repressed memories or tolling.

On the merits, the court dismisses "the Complaints in all three cases because Plaintiff's federal claims are time-barred and the Court declines to consider Plaintiff's state law claims under its supplemental jurisdiction."

Thanks to Timon Amirani, who drafted the motion under my supervision.

The post Attempt to Entirely Seal Title IX Complaint on Privacy Grounds Rejected appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Psych Professor's Lawsuit Over Alleged Contract Nonrenewal Based on Speech About Gender Dysphoria Can Go Forward

[Prof. Allan Josephson (formerly of the University of Louisville medical school) claims his contract wasn't renewed because "he expressed his thoughts on treating childhood gender dysphoria during a panel discussion sponsored by a conservative think tank [the Heritage Foundation]."]

From Josephson v. Ganzel, decided yesterday by Sixth Circuit Judge Andre Mathis, joined by Judges Ronald Lee Gilman and Richard Allen Griffin:

The First Amendment protects popular and unpopular speech alike. Allan Josephson worked as a professor of psychiatry at a public university's [University of Louisville's] medical school. After developing an interest in the medical treatment of childhood gender dysphoria, he began publicly discussing his views on that topic.

In October 2017, he expressed his thoughts on treating childhood gender dysphoria during a panel discussion sponsored by a conservative think tank [the Heritage Foundation]. His commentary was unpopular with his coworkers and supervisors. Josephson believes that his superiors retaliated against him for the views he expressed during the panel discussion, ultimately culminating in the nonrenewal of his contract with the university after more than fifteen years of employment….

Josephson sued, and the Court of Appeals allowed the case to go forward:

Josephson argues that Defendants violated his First Amendment rights when they retaliated against him based on his remarks at the Heritage Foundation event….

Public employers can permissibly limit the speech of their employees in certain circumstances. That is so because when a public employee speaks, "such speech pits the employee's interests in speaking freely against the employer's interests in running an efficient workplace." Generally, the First Amendment protects a public employee's speech if: (1) the speech was on a matter of public concern; (2) the speech was not made pursuant to the employee's official duties; and, assuming the employee can satisfy the first two elements, (3) the employee's interest in speaking on a matter of public concern outweighs the employer's interest "in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees," Pickering v. Bd. of Educ. (1968).

Josephson spoke on a matter of public concern when he participated in the Heritage Foundation panel. Specifically, he spoke about the treatment of children with gender dysphoria. "[C]ontroversial subjects" like "sexual orientation and gender identity" are "sensitive political topics" that "undoubtedly" involve "matters of profound value and concern to the public."

Josephson did not participate in the Heritage Foundation panel as part of his official duties with the Medical School. The Heritage Foundation invited Josephson to speak off campus and paid for his travel expenses to participate. And the moderator advised the audience that Josephson spoke in his individual capacity and not on behalf of an organization. Although Josephson's Division chief duties included giving academic presentations at other universities and before various professional groups, he always did so to "spread the good news" about the Medical School; his panel remarks were therefore unlike his other invited presentations. His panel remarks did not involve meeting with other university leaders or discussing the Medical School. He was not lecturing about his work at another university, nor did he submit his work to the Heritage Foundation for evaluation before receiving an invitation to speak. Simply put, the evidence suggests that the impetus or motivation behind Josephson's panel remarks was the Heritage Foundation's desire for Josephson to share his own opinions on gender dysphoria and not those of the Medical School.

The Pickering balancing inquiry favors Josephson as well. Start with Josephson's interests. He presented his ideas and opinions on gender dysphoria, an issue of substantial public concern. The Supreme Court has "often recognized that such speech occupies the highest rung of the hierarchy of First Amendment values and merits special protection." Josephson was a professor at the Medical School. His panel remarks on gender dysphoria related to his teaching and scholarship as a child psychiatrist.

What about the Medical School's interest in punishing Josephson for interfering with its efficient performance of public services? To answer this question, we consider several factors, including "whether an employee's comments [1] meaningfully interfere[d] with the performance of [his] duties, [2] undermine[d] a legitimate goal or mission of the employer, [3] create[d] disharmony among co-workers, [4] impair[ed] discipline by superiors, or [5] destroy[ed] the relationship of loyalty and trust required of confidential employees." "[A] stronger showing [of government interests] may be necessary if the employee's speech more substantially involve[s] matters of public concern."

Limited evidence suggests Josephson's panel remarks interfered with the Medical School's operation. As chief, Josephson had to, among other things, manage the Division's clinical activities, recruit faculty, assist in training directors, serve on boards and task forces, and mentor faculty. The evidence shows Josephson's remarks inhibited his ability to mentor and lead his Division colleagues. For example, he led and eventually stormed out of a contentious faculty meeting after some attendees voiced their concerns about Josephson's recent remarks. And there is no doubt that Josephson's remarks caused disharmony between him and his colleagues. But outside of this, the evidence does not suggest that Josephson's panel remarks hampered the Medical School's effective operation.

The other factors tip the balance in Josephson's favor. Outside of his ability to mentor and lead Division faculty, there is nothing to suggest that Josephson's remarks interfered with his remaining chief duties or his duties as a psychiatry professor. No doubt, his colleagues voiced their concerns that Josephson's remarks would affect patient care, faculty recruitment and retention, accreditation, and the Medical School's reputation in general. But Defendants could point to no evidence that their concerns were realized or likely to occur. For example, they could not identify any actual impact Josephson's remarks had on patient care. Nor could they identify any person who left the Medical School or turned down an offer to join the faculty based on Josephson's activities. Defendants also conceded that one professor's remarks rarely affected the Medical School's accreditation, and they did not provide any evidence that the Medical School's accreditation was, in fact, affected by Josephson's activities. So Defendants only had concerns, and "[t]he mere 'fear or apprehension of disturbance is not enough to overcome the right to freedom of expression.'" [Details omitted. -EV] …

Considering this, Defendants have provided insufficient evidence that Josephson's remarks had a significant disruptive effect on the Medical School's operations. And any disruptions that followed Josephson's panel remarks were eliminated once Josephson resigned as chief. Given that Josephson spoke on an academic matter of substantial public concern, the Medical School's burden in justifying his February 2019 discharge is heavy. Accordingly, "the Pickering balance strongly favors" Josephson.

Defendants do not meaningfully challenge that Josephson spoke on a matter of public concern during the Heritage Foundation panel or that the Pickering balance favors him. Instead, they contend that Josephson's participation at the event was "pursuant to" his official duties with the Medical School and was thus unprotected speech. Even if Josephson's participation in the Heritage Foundation panel were part of his official duties, that would not alter our conclusion that he engaged in protected speech at that event.

In Garcetti, the Supreme Court held that "when public employees make statements pursuant to their official duties, the employees are not speaking as citizens for First Amendment purposes, and the Constitution does not insulate their communications from employer discipline." Still, Garcetti left open the possibility of an exception to this rule, as the Court declined to address if its analysis "would apply in the same manner to a case involving speech related to scholarship or teaching."

In Meriwether v. Hartop, we answered the question that Garcetti left open. We held that "professors at public universities retain First Amendment protections at least when engaged in core academic functions, such as teaching and scholarship."

Defendants argue that Josephson's Heritage Foundation presentation was made pursuant to his official duties because he discussed his work at the Medical School and the patients he treated there. Although he was not teaching a class, Josephson's panel remarks were on a topic he taught and wrote about as a child-psychiatry expert. Put differently, Josephson's speech stemmed from his scholarship and thus related to scholarship or teaching. As such, Josephson engaged in protected speech because it related to core academic functions….

A reasonable jury could also find that each Defendant was motivated to act, at least in part, by Josephson's panel remarks….

And the court also concluded that, if Josephson's factual account is correct, Josephson's rights were clearly established; the court therefore denied qualified immunity to defendants.

Travis C. Barham, Tyson C. Langhofer & P. Logan Spena (Alliance Defending Freedom) represent Josephson.

The post Psych Professor's Lawsuit Over Alleged Contract Nonrenewal Based on Speech About Gender Dysphoria Can Go Forward appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Prof. Francesca Gino's Libel Claims Against Harvard Business School and Data Colada Dismissed

From today's decision by Judge Joun (D. Mass.) in Gino v. President & Fellows of Harvard College:

Professor Gino is an internationally renowned behavioral scientist, prolific author, researcher, and teacher who has received many awards and considerable media attention for her academic research regarding people's decision-making. She is currently employed by Harvard, as a tenured professor at the Harvard Business School ("HBS")….

The Data Colada Defendants are a trio of male professors and behavioral scientists who, since 2013, have published a blog called "Data Colada." In July 2021, the Data Colada Defendants approached HBS with concerns about perceived anomalies and alleged fraud in the data of four studies in academic articles authored by Professor Gino….

On June 13, 2023, … [HBS] Dean Datar informed Professor Gino that she was being placed on unpaid administrative leave for two years, that she would receive no salary or benefits after July 31, 2023, and that he would request the commencement of tenure revocation proceedings ….

Gino sued Harvard for breach of contract, defamation and related torts, and invasion of privacy, and also sued the Data Colada Defendants for defamation and related torts. The court allowed the breach of contract claim to go forward, based on allegations of various procedural irregularities in the way the Harvard investigation was conducted.

But the court rejected Gino's defamation claim. It concluded that Prof. Gino is a public figure, based on the Complaint's stating "that Professor Gino is an 'internationally renowned behavioral scientist, author, and teacher' who 'has authored or co-authored countless journal publications, business articles, and books,' 'has regularly presented her work at conferences and has been invited to speak at some of the most prestigious colleges and universities in the world,' 'has received numerous honors and awards' internationally, and has had her work 'covered in numerous media outlets.'" It then went to analyze the libel claims this way:

Retraction Notices

The Retraction Notices express HBS's concerns regarding the validity of the data in the four articles published by Professor Gino. The Retraction Notices disclose the bases for these concerns, including detailed appendices explaining the alleged data anomalies and disclosing the forensic assessments conducted. The ultimate conclusion expressed in these Retraction Notices is that, based on the data discrepancies set forth in the appendices, HBS "thus believe[s] the results reported … are invalid due to alteration of the data that affects the significance of the findings." As such, I find the Retraction Notices amount "only to a statement of [HBS]'s evolving, subjective view or interpretation of its investigation into inaccuracies in certain [data] contained in the articles," rather than defamation. Further, the Retraction Notices were "measured and professional" in tone, describing in detail the forensic investigation conducted and declining to directly accuse Professor Gino of data manipulation….

Regarding actual malice, Professor Gino has not plausibly alleged that the Harvard Defendants "either knew that [their] statements were false or had serious doubts about their truth and dove recklessly ahead anyway."

Announcement of Administrative Leave

Professor Gino premises her second defamation claim against the Harvard Defendants on HBS's publication of the text "ADMINISTRATIVE LEAVE" on Plaintiff's HBS faculty page, as well as Dean Datar's email on June 22, 2023, to Professor Gino's colleagues that announced Professor Gino's administrative leave status, while referring to research integrity and the research misconduct allegations.

While the FAC admits that Professor Gino in fact was placed on administrative leave, Professor Gino argues that "under Massachusetts law, even a true statement can form the basis of a libel action if the plaintiff proves that the defendant acted with 'actual malice'"—meaning, in this context, "actual malevolent intent or ill will." But that "exception to the truth defense is not constitutional when applied to matters of public concern." … Where Professor Gino is a public figure, and the issue of research integrity and potential misconduct concerns her colleagues, the FAC fails to state a claim for defamation based on the Harvard Defendants' announcement of her administrative leave status….

The court also rejected the invasion of privacy against Harvard, which stemmed from the "announcement of her administrative leave on the HBS website":

Such a claim requires Professor Gino to "establish that the disclosure was both unreasonable and either substantial or serious." In an employment context, the information must be of a "highly personal or intimate nature" and a "legitimate countervailing interest in disclosure" must not exist.

Professor Gino's administrative leave status is not information of a highly personal or intimate nature, "such as matters concerning her health or her lifestyle." And, though the FAC does allege HBS never previously publicly announced a tenured professor's administrative leave status on its website, it cannot be said that there exists "no legitimate countervailing interest in disclosure." As Dean Datar informed Professor Gino, an intended purpose behind disclosure was to notify others that she would be "unavailable to engage in research, teaching, and mentoring and advising." …

The court likewise dismissed the defamation claims against Data Colada:

Defamation is a disfavored action for which the courts prefer summary disposition. This is especially so for matters of academic and scientific debate….

As with the defamation claims against the Harvard Defendants, the Data Colada Defendants' statements in both the December Report and the blog posts reflect "personal conclusions about the information presented," and they disclose the facts underlying their judgment that there was likely data fraud in the studies, see Conformis, Inc. v. Aetna, Inc. (1st Cir. 2023) ("[A]n opinion is not actionable if it merely draws a conclusion from disclosed non-defamatory facts")….

Professor Gino asserts that the Data Colada Defendants' statements "reasonably would be understood to declare or imply provable assertions of fact," thereby amounting to actionable non- opinion. Regarding the December Report, Professor Gino specifically argues:

Given all of the circumstances, including (i) the statement's title, "Evidence of Fraud in Academic Articles Authored by Francesca Gino; (ii) the statement's assertion that the December Report was "direct evidence" of "fraud" by Plaintiff; (iii) the implied statements that Defendants knew undisclosed defamatory facts, (including the suggestion that the "evidence" in the December Report was a "small subset" of what Defendants had collected); (iv) the authoritative tone (indicating that "individuals" had "approached" Defendants to help "reconcile" "concerns" about Plaintiff's alleged misconduct), the December Report is reasonably understood as a statement of fact: that Plaintiff had committed academic "fraud," and not non-actionable opinion.

While whether Professor Gino in fact committed academic fraud may be proved true or false, "even a provably false statement is not actionable if it is plain that the speaker is expressing a subjective view, an interpretation, a theory, conjecture, or surmise, rather than claiming to be in possession of objectively verifiable facts." In making this determination, I must consider "[t]he sum effect of the format, tone and entire content" of the December Report. "[W]hen an author outlines the facts available to him, thus making it clear that the challenged statements represent his own interpretation of those facts and leaving the reader free to draw his own conclusions, those statements are generally protected by the First Amendment." In contrast, if a statement is "not based on facts accessible to everyone" and the audience is "implicitly … told that only one conclusion [is] possible," the statement does not qualify as a protected opinion.

The December Report constitutes the Data Colada Defendants' subjective interpretation of the facts available to them, as disclosed in the December Report through its thorough discussion of the potential data anomalies observed in Professor Gino's four studies. As set forth in its title, the December Report walks the reader through "Evidence of Fraud in Academic Articles Authored by Francesca Gino"; it does not directly state anywhere that Professor Gino committed fraud. Nor does it state that data tampering definitively occurred, using cautionary language to couch any conclusions. See, e.g., [id. at 5 (data "suggests to us that these eight observations may have been altered" (emphases added)); id. at 18 ("we believe that these observations were manually altered" (emphasis added))]; see also Piccone v. Bartels (1st Cir. 2015) (holding that whether challenged statement constitutes provable assertion of fact requires considering "any cautionary terms used by the person publishing the statement").

In fact, the December Report explicitly acknowledges the limitations of its work and the possibility of conclusions besides tampering by Professor Gino herself. And while the December Report does allege the existence of other evidence of data tampering in Professor Gino's studies, the Data Colada Defendants do not indicate that they are "uniquely situated" to access this additional evidence, nor do they imply that they are "singularly capable of evaluating [Professor Gino's] conduct." Indeed, the December Report notes that the Harvard University investigators could and should consider Professor Gino's other studies themselves for additional evidence of tampering if so desired. And the statements about other potential fraud convey only the Data Colada Defendants' inference that, if a researcher's datasets over a decade show signs of fraud, other such examples may exist….

Further, distinct statements identified by Professor Gino—e.g., statements that individuals had raised concerns with the Data Colada Defendants, that the Data Colada Defendants tried to "identify some of the biggest issues," that they believe Harvard has access to files that could have verified or disputed their concerns—are not actionable because they are neither susceptible to defamatory meaning nor are they alleged to be false, as briefed by the Data Colada Defendants….

The four blog posts similarly evince that the Data Colada Defendants are "expressing a subjective view," based on facts that they disclose in the blog posts, "rather than claiming to be in possession of objectively verifiable facts." The posts analyze each study and the underlying data at length, describe how the Data Colada Defendants reached their conclusions regarding data tampering, and provide many screenshots from and hyperlinks to the primary documents from each study—including the allegedly suspicious data files. [Further details omitted. -EV]

Further, as noted above, Professor Gino's status as a public figure requires her to plausibly allege that the Data Colada Defendants spoke with "actual malice," meaning "knowledge of the statement's falsity or reckless disregard for its truth." Professor Gino argues that the Data Colada Defendants assert in the December Report and the four blog posts that they had "direct evidence" she had manipulated data, (1) despite knowing that data irregularities occur in behavioral science research with respect to data collection and handling, and (2) despite defendant Simonsohn's later concession that he had "no evidence" that Professor Gino had manipulated data—thereby "demonstrating Defendants' malice." These allegations are not plausible.

A plain reading of the December Report does not assert "direct evidence" of fraud by Professor Gino anywhere. Rather, the December Report reads, "We report direct evidence of data tampering in four different datasets from four different published articles," and it goes on further to caution the reader that, "although the evidence can, in most of these cases, rule out malfeasance by co-authors, it cannot definitively rule in malfeasance by Professor Gino. It may be that some research assistant or otherwise unnamed person/people was/were responsible for producing these anomalies." Professor Gino points out that, "as behavioral scientists at leading universities, Data Colada knew or had reason to know that Professor Gino works with research assistants and others and may not have been the person responsible for any perceived anomalies in studies she authored." Indeed, the Data Colada Defendants acknowledged that and took care to inform readers of this possibility. Nor do the blog posts declare direct evidence of data tampering by Professor Gino….

Jeffrey Jackson Pyle represents the Data Colada Defendants.

The post Prof. Francesca Gino's Libel Claims Against Harvard Business School and Data Colada Dismissed appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] #TheyLied Libel Claim Brought by N.Y. Mayoral Candidate Accused of Sexual Assault Can Go Forward

The case is Stringer v. Kim, decided Monday by N.Y. trial court judge Richard Latin; Scott Stringer is a former New York Assemblyman, New York City Comptroller, Manhattan Borough President, and prominent candidate for New York Mayor in 2021, and is apparently running for Mayor again.

Under New York's "anti-SLAPP statute," plaintiff had to show a "substantial basis" for his lawsuit in order for the case to go forward, and the court said that he did (though of course without deciding the facts):

Plaintiff has adequately plead a substantial basis for his claim of defamation. Plaintiff alleges that, on April 28, 2021, Defendant held a press conference in which she falsely accused plaintiff of sexually assaulting her 20 years earlier, while she worked for Plaintiff's campaign. Defendant also allegedly stated that Plaintiff groped her and put his hands down her pants without her consent. Plaintiff further alleges that Defendant repeated these accusations to the press and on social media throughout 2021 and that the accusations were repeated by Congresswoman Maloney in August 2022. These statements, if false, are defamatory per se.

Plaintiff has also adequately pled a substantial basis for actual malice. Plaintiff alleges Defendant engaged in a campaign to ruin his political career after he declined to give her a position in his campaign, and she went to work for his opponent. Plaintiff further alleges that, despite the alleged sexual assault having occurred 20 years earlier, Defendant first raised her allegations during Plaintiff's campaign for mayor, when Plaintiff was gaining momentum in his campaign and the allegations would be widely circulated[.] The defamatory statements were then repeated to the press by Congresswoman Maloney on August 20, 2022, shortly after Defendant attended a campaign event with Maloney, who was running against defendant's mentor.

Thus, for the purposes of the instant motion, Plaintiff has shown a substantial basis in the law for actual malice (see Celle v Filipino Reporter Enterprises Inc. [2d Cir 2000] ["Evidence of ill will combined with other circumstantial evidence indicating that the defendant acted with reckless disregard of the truth or falsity of a defamatory statement may also support a finding of actual malice"]).

Here is the New York intermediate appellate court's decision earlier this year reversing the same trial judge's decision to dismiss the case on statute on statute of limitations grounds:

There is no dispute that defendant's original statements concerning plaintiff were made in April 2021, which is more than a year before this action was commenced, and therefore fall outside the statute of limitations pursuant to CPLR 215(3). Thus, the burden shifts to plaintiff to raise an issue of fact as to whether the statute of limitations has been tolled or whether an exception to the limitations period is applicable.

Here, plaintiff alleges that defendant republished her original defamatory statements concerning him when a third party, then Congresswoman Maloney, was quoted in a newspaper article making reference to those statements. "Republication, retriggering the period of limitations, occurs upon a separate aggregate publication from the original, on a different occasion, which is not merely a delayed circulation of the original edition." Retriggering by republication also requires that the original publisher of the statement participate in or approve of the decision to republish the allegedly defamatory statement.

Here, the pleadings as to the proximity in time between the August 3, 2022 Maloney campaign event where defendant was present, and the subsequent August 20, 2022 New York Post article quoting Maloney, raises an issue of fact as to whether defendant had a role in or authorized the decision to make the allegedly defamatory comments.

Kim also sued Stringer, alleging sexual abuse; you can read the Complaint and the Answer.

The post #TheyLied Libel Claim Brought by N.Y. Mayoral Candidate Accused of Sexual Assault Can Go Forward appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Probation Condition Requiring Defendant to Remove "F Officer Rose" from His Car

From Monday's decision in City of Conneaut v. Wick, decided by the Ohio Court of Appeals, in an opinion by Judge Robert Patton, joined by Judge Mary Jane Trapp:

Appellant, Francis J. Wick ("Wick"), appeals the decision of the Conneaut Municipal Court, sentencing him to five years of unsupervised community control, a fine of $150, payment of court costs, and 30 days of suspended jail time on the condition that he complete an anger management course and remove "defamatory language" from the back of his vehicle….

This case arises from events that occurred on October 27, 2023. Wick was on Conneaut High School property using vulgar and offensive language in the presence of High School staff members and students. Wick admitted to the trial court that he used profanity towards staff and officials that day. Wick was on the property because he had dropped off his daughter but was later told to return and pick her up.

Wick was angry that his daughter had been suspended from school, and there was some confusion about when she was able to return. After shouting profanities at teachers and officials, Wick squealed his tires and left the High School. When Wick arrived at his nearby home, officers were there waiting for him. Wick continued to shout profanities at officers out the windows of his home. On October 30, 2023, Wick again was at Conneaut High School, where Officer Rose was also present, and he shouted profanity at faculty and Officer rose, and again drove off.

Officer Timothy Rose ("Officer Rose") was present during the October 27, 2023, incident. During Sentencing, Officer Rose advised the trial court that sometime after the incident at the High School and Wick's home, he discovered the words "F Officer Rose" written in metal paint pen on the back of Wick's vehicle. Wick stated at sentencing that his daughter had written the statement on a 1996 Ford Explorer that he owned….

Wick entered a plea of no contest to the Aggravated Disorderly Conduct and Disorderly Conduct charges, and [a] Reckless Operation [of a Motor Vehicle] count was dismissed. On the Disorderly Conduct charge, the trial court fined Wick $100. On the Aggravated Disorderly Conduct count, the trial court sentenced Wick to thirty days in jail, suspended, five years of unsupervised community control, and a $150 fine. The trial court further added the conditions that Wick attend anger management treatment and remove the "defamatory" statement regarding Officer Rose from his vehicle. Wick's appeal to this Court only pertains to the sentence imposed for the Aggravated Disorderly Conduct charge….

The appellate court concluded that the trial court used "defamatory language" loosely, meaning "language that is negative in nature directed at a specific person that diminishes their reputation" (rather than in the legal sense, which would require a false factual assertion, absent in "F Officer Rose"). And the court rejected plaintiff's challenge to the constitutionality of the probation condition, on the grounds that it hadn't been properly raised below.

Judge John Eklund dissented:

I believe this case warrants the exercise of our discretion to review this error despite Appellant's failure to object at the trial court.

While a trial court has discretion "in imposing conditions" of community control, that discretion "is not limitless." … To determine whether a community control sanction is an abuse of discretion, a reviewing court must consider whether the sanction: "(1) is reasonably related to rehabilitating the offender, (2) has some relationship to the crime of which the offender was convicted, and (3) relates to conduct which is criminal or reasonably related to future criminality and serves the statutory ends of probation." "All three prongs must be satisfied for a reviewing court to find that the trial court did not abuse its discretion." …

First, I fail to see how the community control condition could be reasonably related to rehabilitating Appellant because Appellant was not the one who put the message on the car. The condition has no redemptive value. The question of whether appellant should have such a message on his car is a separate question from whether the court should order its removal. The best that may be said for the condition is that Appellant might learn not to let his daughter write such things on his car. Or, it might teach Appellant to raise his children to respect police officers. But a failure to respect law enforcement (however odious that may be) is not criminal. Appellant's rehabilitation does not require that he respect Officer Rose. In the end, the goal of a community control sanction cannot be to ensure that defendants, like Winston from George Orwell's 1984, "must love Big Brother."

Second, the condition is not related to the crime for which Appellant was convicted. Appellant was convicted for using "vulgar and offensive language in the presence of students" and "staff members" at the Conneaut High School. The message "F Officer Rose" is not vulgar or profane on its face. The condition can only be said to be related to the crime insofar as Appellant's daughter wrote the message, but we do not even know why she did so (although the reference to it in the record seems to indicate it was related to Officer Rose arresting Appellant). I do not believe such a tenuous relationship satisfies [the relationship-to-crime-of-conviction] prong.

Third, the condition does not relate to conduct that is criminal, or reasonably related to Appellant's future criminality. Again, he did not write it, and, as the majority explains, the message is not defamatory in a legal sense. Its mere presence on the car certainly does not rise to the level of disorderly conduct or any other criminal violation. Apparently, it bothers Officer Rose (apparently not enough to have informed the prosecutor or the court of it until sentencing). It bothers me, too. But, the expression of that opinion – disrespectful as it may be – cannot be said to be reasonably related to Appellant's future criminality.

Because the community control sanction fails to satisfy each of the three prongs of the Jones test, I would hold that the trial court abused its discretion by imposing the condition to remove the message "F Officer Rose" from Appellant's car.

The post Probation Condition Requiring Defendant to Remove "F Officer Rose" from His Car appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Post] An Extraordinary Music-Streaming Scam

[A glimpse into the grim AI-inflected future - and a possible answer to the question "Why does so much music suck on Spotify?"]

Some of you may recall that several months ago the band I play in ("Bad Dog") was embroiled in a rather unpleasant copyright infringement episode (see my earlier blog posting here) in which recordings from an album we had recently released had been copied and distributed to all of the major music-streaming platforms (Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, etc.) without our permission and under new song titles and new (and pretty obviously fictitious) "artist" names.

David Segal of the NY Times picked up the story and published an (excellent) article about it that ran on the front page of the Sunday Times Business Section, which generated a fair bit of buzz in music industry circles.

Shortly after the article came out, I was contacted by someone in the US Attorney's office in NYC, and I was subsequently interviewed for an hour or so by an investigator from that office, to whom I gave as many details as I could about what had happened to us, and to our files. He didn't say—and I didn't ask—what his purpose was in gathering all this information, but I had the impression that they were engaged in some sort of ongoing investigation involving the music-streaming business, and wanted to see if our problem was possibly related somehow to something that they were already looking into.

It turns out there was indeed an ongoing investigation, which has now yielded an indictment, released last week, alleging that Michael Smith, a musician from North Carolina, "orchestrated a scheme to steal millions of dollars of musical royalties by fraudulently inflating music streams on digital streaming platforms such as Amazon Music, Apple Music, Spotify, and YouTube Music."

The DOJ announcement of the unsealing of the indictment is available here; the full-text of the indictment is here.

The indictment contains some pretty astonishing details; I urge anyone interested in how the music industry works these days to look it over.

Here's how Smith's scam allegedly worked (all quotations are from the indictment):

First, he contracted with an AI firm specializing in music production (unnamed, and referred to as "Co-Conspirator 3" in the indictment) to deliver newly-created "songs" to him, and to transfer all the rights in those songs to him. The quality of this material may be inferred from the fact that the contract obligated CC-3 to deliver up to 10,000 "songs" to Smith every month, and the indictment alleges that between 2019 and 2024, CC-3 produced hundreds of thousands of songs for Smith.

SMITH then "created randomly generated song and artist names for audio files so that they would appear to have been created by real artists rather than artificial intelligence."

The indictment gives these examples. First, an "alphabetically consecutive selection of 25 of the names of the AI songs SMITH used:

"Zygophyceae," "Zygophyllaceae," "Zygophyllum," "Zygopteraceae," "Zygopteris," "Zygopteron," "Zygopterous," "Zygosporic," "Zygotenes," "Zygotes," "Zygotic," "Zygotic Lanie," "Zygotic Washstands," "Zyme Bedewing," "Zymes," "Zymite," "Zymo Phyte," "Zymogenes," "Zymogenic," "Zymologies," "Zymoplastic," "Zymopure," "Zymotechnical," "Zymotechny," and "Zyzomys."

Second, an alphabetically consecutive selection of 25 of the names of the "artists" of the AI songs SMITH used :

"Calliope Bloom," "Calliope Erratum," "Callous," "Callous Humane," "Callousness," "Callous Post,"(Uncle Callous!!) "Calm Baseball," "Calm Connected," "Calm Force" "Calm Identity" "Calm Innovation" "Calm Knuckles" "Calm Market" "Calm The ' ' , ' ' Super," "Calm Weary," "Calms Scorching," "Calorie Event," "Calorie Screams," "Calvin Mann," "Calvinistic Dust," "Calypso Xored," "Camalus Disen," "Camaxtli Minerva," "Cambists Cagelings," and "Camel Edible."

To get his songs posted to the music-streaming platforms, Smith contracted with at least two different music distribution companies—a "Manhattan-based music distribution company ("Distribution Company-1") [and] a Florida-based music distribution

company ("Distribution Company-2″)."

Meanwhile, Smith created several thousand fake email accounts which he then used to create fake "bot" user accounts at the major streaming platforms. At one point he had over 10,000 active bot accounts on the major platforms. He then programmed the bots so that they would stream "his" songs, over and over again, 24/7.

"After registering the Bot Accounts, MICHAEL SMITH, the defendant, then caused the Bot Accounts to continuously stream songs he owned using the following methods:

a. SMITH used cloud computer services so that he could use many virtual computers at the same time.

b. SMITH used some of the Bot Accounts on each virtual computer at the same time. SMITH typically used the web players for each of the Streaming Platforms, and had a number of Bot Accounts simultaneously streaming music on separate tabs in internet browsers on the virtual computers.

c. SMITH purchased-and subsequently modified-"macros," or small pieces of computer code that automatically continuously played the music for him."

As a result, Smith "obtained millions of dollars in royalties based on the artificially inflated streams of his music."

"On October 20, 2017, MICHAEL SMITH, the defendant, emailed himself a financial breakdown of how many streams he was generating each day and the corresponding royalty amounts. In the email, SMITH wrote, in substance and in part, that he had 52 cloud services accounts, and each of those accounts had 20 Bot Accounts on the Streaming Platforms, for a total of 1,040 Bot Accounts. He further wrote that each Bot Account could stream approximately 636 songs per day, and so in total SMITH could generate approximately 661,440 streams per day. SMITH estimated that the average royalty per stream was half of one cent, which 7 would have meant daily royalties of $3,307.20, monthly royalties of $99,216, and annual royalties of $1,207,128."

Nice work if you can get it!

Smith has been charged with wire fraud, conspiracy to commit wire fraud, and money laundering. Notice: no copyright infringement here, unlike in our Bad Dog example, because whatever else Smith might have been doing, he did own the copyright in the "songs" that were composed for him.

Needless to say, I have absolutely no idea whether these allegations against Smith are true, let alone whether they can be proved beyond a reasonable doubt.

But it's pretty clear that whether or not Smith is guilty as charged, someone could have done—and may still be doing—what he's been charged with. That is, as a technical matter, nothing in what Smith is alleged to have done strikes me as impossible, or even particularly difficult, at least for someone who has substantial programming chops—like, say, your clever teenage nephew. And given the money that can be made by a scam like this, it's hard to believe that nobody else is in on the game.

And that, I have to say, bums me out. It's like Gresham's law: bad music will chase out good music. If the streaming services are clogged up with garbage, real musicians will be less inclined to use them to distribute their music. And that, I would say, is a real loss.

The post An Extraordinary Music-Streaming Scam appeared first on Reason.com.

[Steven Collis] On the Responsibilities That Come with the Freedom to Speak Freely

[The best practitioners of the freedom of speech are those who do not assume that everyone who disagrees with them operates from bad motives.]

In my continuing series related to my new book Habits of a Peacemaker, this next post seems especially apropos since today is the anniversary of the September 11 attacks. Peacemakers—defined for my purposes as those among us who can have productive conversations about hard topics—generally assume the best about the people with whom they are conversing, regardless of their identities or even deeply held beliefs about controversial issues. Below is an excerpt from Habits Chapter 3, "Assume the Best About People":

Some time ago, I received an unusual email. It was from two high-level federal judges.… One had been appointed by President Barak Obama, the other by President Donald Trump. They informed me that once a month, they and a group of other … judges met together in their private capacities for a prayer breakfast. This was not a public event, not a spectacle where politicians and media showed up to try to garner favor with the voting public.

It was private. Most people never learn of it. The judges—of different faiths and very different political and judicial ideologies—met together throughout the year to enjoy breakfast and pray with one another, usually about people in their lives who were suffering. They were wondering if I would be willing to come and talk with them about one of my books [one not directly related to law].

I agreed. I … met them … early one morning. Outside, several news outlets were setting up cameras for a story about a case some of these jurists would hear later in the morning.

As soon as I entered the building, one of the judicial assistants lead me through security, down a narrow hall, and into a small conference room, where the judges eventually joined. To see them all sitting together, people who are often portrayed as being at one another's throats, was touching to me. Despite their very real differences, they recognized the good in one another and the parts of their identities they had in common, and they shared those over a bite to eat. Like everyone else in our world, they worried over their loved ones, they expressed concern over people they personally knew who were suffering, and they shared empathy with each other over their very human struggles.

I wish everyone could see people like this in that setting.

Their example provides a valuable lesson. This may come as a shock, but the world does not look like this:

Those who agree with you Monsters FoolsYet far too many of us have come to see reality this way. The social media silos mentioned earlier have contributed to that attitude. We are convinced that if someone does not come to the same conclusion as we have about a particular issue, then the only explanation must be that they have nefarious motivations or are ignorant. We are so self-assured of our own righteousness and vast knowledge on a particular topic that we have decided anyone who disagrees must be either a bigot, a buffoon, or worse. If we pause to get out of our own heads for just a moment, we will realize that such a view of the world can't possibly be true.

The people around us with whom we would like to have productive conversations are, we know, often good people. They are family members, coworkers, longtime friends. We know they strive to do right for their children and parents and siblings. We know they try to do a good job for their employers. But for some reason, on the most divisive topics, they transform in our minds to some sort of sinister actor we cannot trust. That type of thought distortion is nonsensical, but we all are guilty of it from time to time.

To be clear, I am not naive. The world does have bigots, despotic communists, fascists, criminals, power-hungry tyrants, and any other manner of evil actors; and fools do abound. But remember who we're talking about in this book: our family members, coworkers, and close associates—the type of people with whom we can have fruitful dialogues. The chances that any or all of them fall into one of those categories is slim, unless you are hanging around with a very different crowd than I am. The very fact that you are reading this book suggests to me that is highly unlikely.

That brings me to an important habit of peacemakers. They assume the best about people and their intentions. If they disagree with someone, they squelch the urge to assume the person has bad motives. They recognize it is possible that the person in question has less information than they do. All of us can do the same.

With our newfound intellectual humility, we now know that it is just as likely that the person in question has more or different information. They may also be aware of concerns that never crossed our mind given our limited perspective. If our goal is to be a peacemaker who can find solutions to the problems that trouble us most, then our purpose should be to learn and understand where other people are coming from and why. The remainder of this chapter offers practical tips for how to do just that. At worst, we'll discover arguments or information that challenge our views and that we need to take into consideration. At best, we'll come to understand the world better and will be even more equipped to tackle its problems.

The post On the Responsibilities That Come with the Freedom to Speak Freely appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers