Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 214

December 4, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Court Rejects College Basketball Player's Defamation Suit Against Coach (Stemming from Dispute About Alleged Racism)

From yesterday's N.C. Court of Appeals decision in Fox v. Lenoir-Rhyne Univ., written by Judge Fred Gore and joined by Chief Judge Chris Dillon and Judge Donna Stroud:

Plaintiffs … were recruited to play women's basketball at Lenoir-Rhyne University …. During the height of COVID-19 in the 2020-2021 basketball season, there were racial tensions within the basketball team that caused the coaches and some administrative personnel to hold a meeting with the team. The team agreed to limit their team communication to only basketball-related and team goal-oriented discussions. Plaintiff Fox organized a "Symposium" for the basketball team and other university administrators to discuss racial prejudice, and later organized a second symposium, "The Talk," open to the entire university, to further discuss racial prejudice. Plaintiff Fox alleges the coaches sought to "retaliate" against her and other African American teammates after these events.

Plaintiffs attested in their affidavits that they were forced off the basketball team at the end of the 2020-2021 basketball season. Plaintiff Fox had a meeting with the coaches in which the coaches told her she did not fit into the culture of the team and that she would not be welcomed back onto the team for the 2021-2022 basketball season. The coaches offered to still give plaintiff Fox her full scholarship for the 2021-2022 basketball season. [Further details of actions taken with respect to to other plaintiffs omitted. -EV] …

{Plaintiff Fox [later] published a letter on social media, entitled "An Open Letter to Lenoir-Rhyne University" along with multiple social media pictures entitled, "The Racist 'Culture' of Lenoir-Rhyne University," "Quotes From Racist Teammates," "The Coaching Staff," "The NCAA & LR," and "Ignorance." Within the letter and social media posts, plaintiff Fox made claims of racism against coaches, basketball teammates, Lenoir-Rhyne, and claimed multiple players were forced to leave the basketball team because of racism.}

In response, Lenoir-Rhyne's president, Frederick Whitt, published a letter to the entire Lenoir-Rhyne community in which he stated the following:

Yesterday, a former student-athlete posted a number of false claims on social media, including that she was dismissed from the women's basketball team for speaking out against racism and advocating for social justice. Lenoir-Rhyne flatly disagrees with this student's version of events. Her dismissal from the basketball team was a legitimate coaching decision, and suggestions to the contrary are simply false.

The court held, without much elaboration, that this statement was, as a matter of law, not libelous. It also rejected plaintiffs' contract claims, concluding that the university acted consistently with any written or oral contracts.

Charles E. Johnson, David C. Kimball, and Spencer T. Wiles (Robinson Bradshaw & Hinson, P.A) represent defendants.

The post Court Rejects College Basketball Player's Defamation Suit Against Coach (Stemming from Dispute About Alleged Racism) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: December 4, 1933

12/4/1933: Nebbia v. New York argued.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: December 4, 1933 appeared first on Reason.com.

December 3, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Esquire Allegation that President Bush Sr. Pardoned His Son Neil Bush

Esquire posted an item Dec. 3 titled "A President Shouldn't Pardon His Son? Hello, Anybody Remember Neil Bush?" and subtitled "Nobody defines Poppy Bush's presidency by the fact that he pardoned his progeny. The moral: Shut the fck up about Hunter Biden, please." It relates some of Neil Bush's exploits, and states:

[T]his lucky American businessman['s] … father exercised his unlimited constitutional power of clemency to pardon the Lucky American Businessman for all that S&L business way back when. The president's name was George H.W. Bush. The Lucky American Businessman was his son, Neil ….

However, as others have noted (and see also some of the comments to the article), the Justice Department pardon and clemency site doesn't appear to have any record of any pardon to Neil Bush: I've checked the name search function, the Bush Sr. pardon list, and the Bush Sr. commutations list. A 2003 Washington Post article that describes Neil Bush as "the latest manifestation of a long tradition in American life—the president's embarrassing relative" doesn't mention any pardon or clemency, or even any conviction. It says,

In the late '80s and early '90s, Bush embarrassed his father, George H.W. Bush, with his shady dealings as a board member of the infamous Silverado Savings and Loan, whose collapse cost taxpayers $1 billion.

Now Bush has embarrassed his brother George W. Bush with a made-for-the-tabloids divorce that featured paternity rumors, a defamation suit and, believe it or not, allegations of voodoo.

But nothing about a criminal conviction (though he had to pay $50,000 to settle a civil lawsuit filed by federal regulators) or a pardon or commutation. I searched for news stories that mentioned Neil Bush and a pardon or commutation, and found several stories (e.g., this one) that mentioned both Neil Bush being an embarrassment and Roger Clinton being pardoned. If there had been a Neil Bush pardon as well, one would expect them to have noted it, but they didn't.

I did find an assertion about a Neil Bush pardon on Dec. 2 on an Indian site Times Now News, but that has no support for the assertion, either. I also found a 2006 Lansing State Journal article that discussed Dick Cheney's accidental shooting of a hunting buddy, and added, "What if Harry Whittington dies? Ten to one, President Bush has a 'pardon' waiting in the wings (a la Neil Bush of 1980s savings-and-loan fame), which says, if you're my man, accountability is not an option." But there too there were no details of any such pardon.

Is there some evidence of Neil Bush being pardoned that I'm missing?

The post Esquire Allegation that President Bush Sr. Pardoned His Son Neil Bush appeared first on Reason.com.

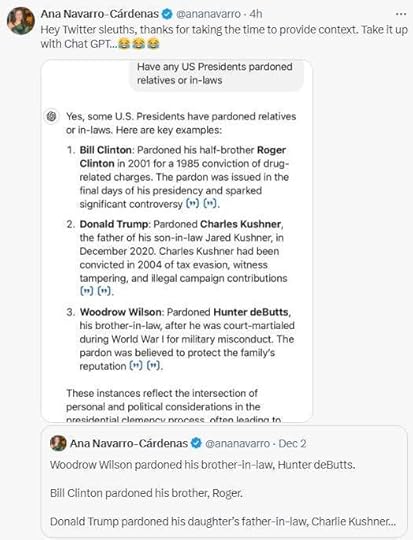

[Eugene Volokh] CNN, The View Commentator Ana Navarro-Cárdenas Cites Apparent ChatGPT Hallucination

Isaac Schorr (Mediaite) reports that "The View's Ana Navarro-Cárdenas" posted a tweet defending President Biden's pardon of his son by stating, among other things, "Woodrow Wilson pardoned his brother-in-law, Hunter deButts." But apparently Wilson's never had or pardoned a brother-in-law with that name, Schorr reports. And Navarro-Cárdenas' defense (after being called on her original post by Twitter users) seems to be to point to ChatGPT:

The Twitter comments are quite amusing. See also The Independent (Kelly Rissman).

UPDATE: Apologies for my error: I had originally written "CNN The View Commentator …," but I should have written "CNN, The View Commentator" (and I've now corrected it). Ana Navarro-Cárdenas is a commentator both on CNN and The View. Thanks to commenter jdgalt1 for pointing this out!

The post CNN, The View Commentator Ana Navarro-Cárdenas Cites Apparent ChatGPT Hallucination appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Court Rejects Promissory Estoppel Claim by Lawyer Whose Job Offer Was Revoked for Speech About Israeli Retaliation Against Gaza

From Chehade v. Foley & Lardner, LLP, decided today by Judge Sharon Johnson Coleman (N.D. Ill.):

The following facts are accepted as true for the purpose of resolving Defendant's partial motion to dismiss.

Plaintiff is an Arab Muslim woman who graduated from Georgetown University Law Center in 2023. While in law school, Plaintiff worked at Defendant's Chicago law office as a summer associate during Summer 2022. On July 29, 2022, Defendant offered Plaintiff a position as a full-time associate attorney, starting in Fall 2023, after Plaintiff's law school graduation.

When applying for summer associate positions, Plaintiff alleges that a law firm's commitment to diversity and retaining diverse associates was important to her as an Arab Muslim woman. Because Plaintiff saw no references to either "Muslim" or "Arab" in Defendant's recruiting materials and learned that Defendant had no specific affinity group for Muslim or Arab attorneys, Plaintiff decided to discuss her concerns with Alexis Robertson, Defendant's Director of Diversity and Inclusion. In July 2022, Plaintiff spoke with Robertson to ensure that Defendant would support her "authentic self." Plaintiff alleges that Robertson promised her that Defendant "valued and supported [her] Arab Muslim heritage and perspective and embraced her history and values." Plaintiff alleges that Robertson's assurances were critical to her decision to accept the full-time employment offer and not pursue other job opportunities.

Plaintiff was scheduled to start her job on October 23, 2023. In the weeks leading up to the scheduled start date, Plaintiff, a long-time supporter of Palestinian human rights, spoke out about Israel's bombing of the civilians of Gaza following the Hamas attack against Israel on her personal social media accounts and at an October 11, 2023 meeting at the City of Chicago's City Hall.

Plaintiff alleges that, prior to her scheduled start date, Defendant began investigating her background and found her social media posts speaking out in support of Gaza. Plaintiff alleges that Defendant's management personnel, including Robertson, then created a plan to rescind Plaintiff's employment offer. On October 21, 2023, Lisa Noller, a partner and chair of Defendant's litigation group, asked Plaintiff to attend a meeting the following day at Defendant's Chicago office to discuss Plaintiff's social media presence. Plaintiff reached out to Robertson for guidance and support, but Robertson never responded.

On October 22, 2023, Plaintiff attended the meeting with Noller and Frank Pasquesi, the managing partner of Defendant's Chicago office. During the meeting, Plaintiff alleges that she was interrogated in a hostile manner about her student activism, community associations, remarks at the October 11, 2023 City Hall meeting, and social media posts about Hamas's attack and Israel's response. Plaintiff alleges that she was also interrogated about her previous leadership role in Law Students for Justice in Palestine ("SJP"), a Georgetown University Law Center student organization, and SJP's recent posts about the conflict, despite Plaintiff's contention that she was no longer involved in SJP after graduation. Following the meeting, and later that same day, Defendant revoked Plaintiff's employment offer.

Plaintiff sued, alleging, among other things, promissory estoppel, which is cousin to breach of contract. But the court dismissed that claim:

The salient question here is whether Robertson's statements that Defendant valued and supported Plaintiff's Arab Muslim heritage and perspective and embraced her history and values constituted an unambiguous promise that Plaintiff's employment offer would not be rescinded for her activism and advocacy efforts that she viewed as supportive of her Arab Muslim heritage. The Court holds that it does not.

Plaintiff offers no evidence to support a finding that Defendant's promise of support was an unambiguous promise to not penalize Plaintiff for any actions she took as long as she believed they were in support of her Arab Muslim heritage. To conclude otherwise would mean that Plaintiff would have a "get out of jail free card" for any action that she took, even if it violated Defendant's values and policies, due to her status as an Arab Muslim woman.

Plaintiff further alleges that Robertson knew Plaintiff was active in the Arab Muslim community, and thus Robertson's statements meant that Defendant would support Plaintiff's activism. To support her argument, Plaintiff attaches her resume and an essay she authored as exhibits to her response brief to show that Defendant was aware of her involvement with SJP and her experience as an Arab Muslim woman. But neither Plaintiff's alleged facts nor the exhibits reasonably impute knowledge of Plaintiff's activism to Robertson, much less Defendant. Nor does Plaintiff allege that she had conversations with Robertson about such activism.

The case Plaintiff cites is also unpersuasive. In Dugas-Filippi v. JP Morgan Chase, N.A. (N.D. Ill. 2014), the court found that an employer's oral promise that plaintiff would not be fired if she took six-month paid discretionary leave was sufficiently clear and definite to support a promissory estoppel claim where plaintiff was fired for taking the six-month discretionary leave despite the employer's at-will policy.

Here, Robertson's statements made no promise that Plaintiff's employment would not be rescinded. Instead, the statements only concerned support for Plaintiff as an Arab Muslim woman. here was no implicit promise that Plaintiff had total job protection no matter what she did or said so long as she believed those actions were related to her ethnicity, religion, or association.

Plaintiff essentially asks the Court to conclude that the parties understood that the promise of support implied a promise of job security regardless of Plaintiff's actions. However, the facts do not support the existence of a common understanding among the parties that would transform Robertson's statements of support into a promise to not rescind Plaintiff's employment offer. The Court finds that there was no unambiguous promise and no common understanding among the parties to support a promissory estoppel claim.

Plaintiff also sued for discrimination based on ethnicity, religion, and association; those claims weren't the subject of a motion to dismiss, and still remain. Note that Illinois law restricts private threats aimed at speech related to candidates or ballot measures:

Any person who, by force, intimidation, threat, deception or forgery, knowingly prevents any other person from (a) registering to vote, or (b) lawfully voting, supporting or opposing the nomination or election of any person for public office or any public question voted upon at any election, shall be guilty of a … felony [and shall be subject to civil liability].

This prohibition on "threat[s]" may cover not just threats of crime but also threats of economic retaliation: Thus, for instance, federal law bans "intimidat[ing], threaten[ing], coerc[ing], or attempt[ing] to intimidate, threaten, or coerce any other person for the purpose of interfering with the right of such other person … to vote as he may choose" has been interpreted as prohibiting threats of economic retaliation. Likewise, the Fair Housing Act makes it illegal "to coerce, intimidate, threaten, or interfere with any person … or on account of his having aided or encouraged any other person in the exercise or enjoyment [of housing nondiscrimination rights]," and courts have interpreted this as barring the firing of employees who rented to black and Mexican-American applicants, and barring the denial of agency funds to an organization that complained about a discriminatory permit denial.

But, unlike the statutes in some other states (and ordinances in some cities and counties, including in Urbana), the Illinois statute doesn't extend to job discrimination based on advocacy of ideological views that aren't directly tied to elections.

Gerald L. Pauling and Tracy M. Billows (Seyfarth Shaw LLP) represent defendant.

The post Court Rejects Promissory Estoppel Claim by Lawyer Whose Job Offer Was Revoked for Speech About Israeli Retaliation Against Gaza appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] More Leaks in the NY Times About The "Supreme Court Ethics Debate"

Another day, another leak story in the New York Times. This time, Jodi Kantor turns her attention to the Supreme Court's "ethics debate." This piece is far less earth-shattering than Kantor's prior reports. The biggest reveal is that Justice Gorsuch wrote a ten-page memo opposing any efforts to make the ethics code "enforceable." Everything else reported either reflects what the Justices have said in public, or can be reasonably inferred from what the Justices said in public. The bigger story, of course, is that leaks are still coming from the Court--and these leaks are designed to impugn and attack those on the "wrong" side of legal issues.

Let's go through it.

First, we learn that Judge Robert Dow, the Chief's Counselor, prepared the first draft:

In May 2023, the chief justice made a public concession, saying the court could take further steps to "adhere to the highest standards" of conduct. Three months later, he gave his colleagues the first draft of the code, prepared by Judge Robert M. Dow Jr., a staff member who advises the chief justice. It was modeled on the one for federal judges, according to several people familiar with the process.

Relatedly, there is an office at the Court that provides ethics advice, though some justices do not seek it "consistently." I'm not sure this fact has been reported before:

While a legal office at the court dispenses ethics advice to justices upon request, the counsel is not binding, and not all the justices have consistently sought it out, according to several people familiar with the office.

Second, the Court's progressives supported a code that can be enforced. Justices Kagan and Jackson (but not Sotomayor) have said as much in their public remarks. Sotomayor also has gotten in trouble for her book events.

All three liberals — Justices Sotomayor, Kagan and Jackson — supported enforcement.

In an apparent attempt to make a higher level of scrutiny palatable to their colleagues, Justice Kagan proposed an initial step, involving a small group of veteran federal judges, according to people familiar with the discussions. She sketched out what she called a "safe harbor" system that would give the justices incentive to consult the judges about ethics issues. Later, if the justices were criticized — say, for accepting a gift — they could respond that they had obtained clearance beforehand.

"There are plenty of judges around this country who could do a task like that in a very fair-minded and serious way," Justice Kagan said at a public appearance this year.

Third, the Court's conservatives were not interested in negotiating on this point. Here, Kantor repeats her claim about the Trump immunity decision--there was no attempt to play ball with the liberals.

That modest proposal went nowhere.

…

The three liberal justices insisted that the rules needed to be more than lofty promises. But their argument never had a chance.

Fourth, the liberals signed the code, even though it lacked any enforcement mechanism. This was the best they can do. Yet, Kagan has continued to criticize it publicly.

In the fall of 2023, Chief Justice Roberts, seemingly determined to emerge with something to show the nation, circulated a revised version of the new code and urged his colleagues to sign it, according to people from the court. It had no means of enforcement. The liberal justices decided this was the best they could get, at least for the moment. All nine members of the court signed.

Fifth, the villain of the story is Justice Gorsuch. Kantor reveals that Gorsuch wrote a ten-page memorandum opposing it.

Justice Gorsuch was especially vocal in opposing any enforcement mechanism beyond voluntary compliance, arguing that additional measures could undermine the court. The justices' strength was their independence, he said, and he vowed to have no part in diminishing it.

The justices began discussing the proposal inside their private conference room and through memos. One from Justice Gorsuch, raising questions and cautions, stretched to more than 10 pages.

This is a reveal not only of the memo, but that it was discussed in conference, and subsequent writings. For the second time in a few months, Kantor has now revealed a private correspondence from Gorsuch. In September, she wrote about Gorsuch's note to Roberts about the Trump immunity decision.

Sixth, Kantor also links Gorsuch's opposition to the code with his general opposition to administrative regulations:

Justice Gorsuch, Mr. Trump's first appointee to the court, is known for his no-one-tells-me-what-to-do streak, with warnings of government overreach and a record of libertarian, sometimes-unpredictable rulings. As a teenager, he watched his mother, then the head of the Environmental Protection Agency, face a bruising congressional investigation into the mismanagement of a toxic waste program and eventually resign.

At the time the justices were debating the ethics questions, Justice Gorsuch was working on a book asserting that Americans were afflicted with too many laws. He warned colleagues that enforcement could undermine the independence of the court by putting other figures in a position to judge the justices, according to several people familiar with the discussions. Justice Alito echoed some of those concerns.

This sort of reporting is not just inferential. She seems to be relaying how Gorsuch tied together his new book and the ethics code--or at least how those on the Court perceived Gorsuch's comments. I suspect some of Gorsuch's colleagues were none too pleased with his book talk during the conference.

Seventh, Kantor writes that Alito and Thomas said those who support the code were being political. Alito said as much to the Wall Street Journal, so nothing surprising here.

In the private exchanges, Justice Clarence Thomas, whose decision not to disclose decades of gifts and luxury vacations from wealthy benefactors had sparked the ethics controversy, and Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. wrote off the court's critics as politically motivated and unappeasable.

Eighth, Kantor explains the deliberations about the ethics code were super-super secret:

The discussions were treated with extra secrecy because they were so sensitive, according to people from the court. Instead of the usual legal issues, the justices were contending with controversy about finances and gifts from friends, and some of the ground rules of their own institution.

But no so secret that she didn't get the goods.

Ninth, Kantor offers these comments on sourcing

To piece together the previously undisclosed debate, The Times interviewed people from inside and outside the court, including liberals and conservatives, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the proceedings and the justices' thinking. This article also draws upon public statements by the justices, who declined to comment.

It is significant that Kantor indicate she spoke to both "liberals and conservatives." Past reporting did not have this note. It is also true that the Justices "declined to comment" on the article, but that doesn't mean the Justices did not speak to Kantor.

So who leaked? Well, here is what I wrote about Kantor's article on the Dobbs leak:

Second, and I alluded to this point in my earlier post, Justice Kagan is absent from this reporting. There is absolutely nothing about what she thought or did during these deliberations. There are insights into all of the other eight Justices, but nothing on Kagan. This isn't new. Back in the day when Biskupic got the scoops, Kagan was also largely absent. I think it likely that Kagan, or at least Kagan surrogates, are behind these leaks. If Kagan is willing to publicly undermine her colleagues in a speech at the Ninth Circuit, why would she do any less off-the-record? Moreover, this entire story is consistent with Kagan's MO, and describing the Court as bending over backwards for Trump.

This passage accurately describes Kantor's most recent article, if you substitute the emphasized text with "and criticizing the code for not being enforceable."

Also noticeably absent are Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh. They appear nowhere in the story. Even as Gorsuch is thrown under the bus, and Alito and Thomas are criticized.

Anyway, Merrick Garland still has not resigned. Nor has Chief Justice Roberts.

The post More Leaks in the NY Times About The "Supreme Court Ethics Debate" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Join Me in Donating to Reason

I just to Reason, to support their excellent coverage and analysis. We are editorially independent of Reason, and contributions to them don't support us. (We split our modest advertising revenue with them, and they provide technical and other services.) My donation just reflects my respect for the work they do; I don't always agree with it, but I think it's on balance a huge contribution to public debate.

You can donate yourselves , if you are so inclined. To quote their pitch this year,

To help us keep an eye on the state while also keeping our chill, Reason relies on the generosity of its readers, listeners, and viewers, not (heaven forbid) the government. The Webathon is critical to funding our work, from hard-hitting investigations to thoughtful commentary, while also fostering a community of freedom-loving individuals. We count on contributions both from grizzled veterans of the liberty movement and from bright-eyed and bushy-tailed folks discovering these ideas for the first time in our pages, pods, and videos. For 2024, we're shooting for $400,000….

In a shouty, partisan world, Reason offers calm, principled journalism—and a little bit of fun. With your generous support, we can produce fearless reporting and incisive analysis. But we know you're probably here for the swag, so we've got you covered:

• $50: A Reason Plus subscription—ad-free browsing, early access to the magazine, commenting privileges, and exclusive events.

• $100: All of the above PLUS a Reason-branded phone wallet.

• $250: Everything at the $100 level PLUS an Abolish Everything t-shirt to spark conversation (or arguments) wherever you go.

• $500: All of the above PLUS a cozy Reason-branded blanket.

• $1,000: All the perks of the $500 level PLUS an invitation to Reason Weekend, a Torchbearer pin, and a podcast shoutout.

• $5,000: All previous rewards PLUS lunch with a Reason editor in Washington, D.C., or your moment of fame as Donor of the Week on the podcast.

• $10,000: Everything up to $5,000 PLUS a ticket to Reason Weekend (for first-time attendees).Since Reason Foundation is a 501(c)(3), you also get a little tax break when you donate, which is extremely on-brand….

The post Join Me in Donating to Reason appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Eighth Circuit Grants Rehearing En Banc as to Whether "Equity Training" Requirement for Public Employees Violates First Amendment, …

The court just agreed to this last Wednesday; here's the earlier panel decision (Henderson v. Springfield R-12 School Dist.)—which will now be reconsidered—written by Eighth Circuit Chief Judge Steven Colloton and joined by Judges James Loken and Jane Kelly:

During the 2020-21 school year, the school district required employees to attend a presentation entitled, "Fall District-Wide Equity Training." Attendees were paid for their time and received professional-development credit.

The school district provided in-person and virtual training. At the in-person training, school officials instructed the attendees on how to become "Anti-Racist educators, leaders and staff members." The district defined "anti-racism" as "the work of actively opposing racism by advocating for changes in political, economic, and social life." The presenters cautioned that actions like practicing color-blindness and remaining silent about racism perpetuated white supremacy.

The presenters stated, "We want to stress that we are not calling you as an individual a white supremacist. That being said, certain actions or statements … can support that structural system of white supremacy." The presenters also displayed an "Oppression Matrix" that categorized various social groups as a privileged, oppressed, or border group. For example, within the category of race, the matrix identified white people as a privileged social group, biracial people as a border group, and Asian, Latina/o, black, and native people as oppressed social groups. At the virtual training, the school district provided similar instruction.

Some employees were also required to complete online modules in which they watched videos, read articles, and answered multiple-choice questions relating to equity and diversity. For example, one question asked: "When you witness racism and xenophobia in the classroom, how should you respond?" Employees could select one of two options: (1) "Address the situation in private after it has passed"; or (2) "Address the situation the moment you realize it is happening." The module deemed the second option the correct answer. If the employee selected the first option, then a message appeared explaining why the choice was "incorrect." To complete the module, employees had to select the "correct" answer.

The training sessions were interactive. At the in-person training, attendees were asked to speak with one another about specific prompts related to the presentation's content. In the online training, participants were similarly required to speak with other virtual attendees. Both training sessions included an exercise called "Four Corners," in which attendees had to hold up a sign stating whether they agreed or disagreed with various prompts, such as "I believe my students or staff feel safe in Springfield" and "I believe [the school district] provides an engaging, relevant and collaborative learning and working environment.

At both training sessions, instructors displayed a slide entitled "Guiding Principles" in which one line read: "Be Professional—Or be Asked to Leave with No Credit." No attendee was asked to leave, denied pay, or refused credit because of his or her conduct during the sessions. No employee discipline resulted from these sessions.

Brooke Henderson attended the virtual training. Henderson is a Section 504 Process Coordinator. At the training, Henderson expressed her view that Kyle Rittenhouse acted in self-defense during a Black Lives Matter protest in 2020. The presenter responded that Henderson was "confused" and "wrong." Henderson alleges that after this dialogue with the presenter, she stopped speaking out of fear that she would be asked to leave for being unprofessional. She also alleges that during the "Four Corners" exercise, she responded that she agreed with some prompts solely because she feared that if she disagreed, she would be asked to leave without receiving credit or pay. Henderson also completed the virtual modules. She alleges that she selected answers with which she did not agree so that she would receive credit for the training.

Jennifer Lumley attended the in-person training. Lumley is a secretary. At the training, Lumley stated that she did not believe that all white people were racist, and that people of other races could be racist. She shared a personal anecdote about her niece-in-law, a black woman who married a white man, and how "some black people had told her she did not 'count' as black anymore." The presenter responded that black people could be prejudiced, but not racist. Lumley also stated that she did not believe that she was privileged because she grew up in a low-income household. The presenter responded that Lumley "was born into white privilege." Like Henderson, Lumley alleges that after this interaction, she stopped speaking because she feared that she would be asked to leave.

Plaintiffs sued, but the court concluded that their First Amendment rights weren't violated, because they were not punished for their speech or lack of speech:

The plaintiffs suggest … that they were punished because they were "shamed" and "forced to assume the pejorative white supremacist label for their 'white silence.'" They rely on Gralike v. Cook (8th Cir. 1999), aff'd by the Supreme Court (2001), where this court held unconstitutional a Missouri law requiring that state election ballots identify any candidates who opposed or refused to express a view on congressional term limits. We concluded that the law "threaten[ed] a penalty that is serious enough to compel candidates to speak—the potential political damage of the ballot labels." We explained that the labels were "phrased in such a way" that they were "likely to give (and we believe calculated to give) a negative impression not only of a labeled candidate's views on term limits, but also of his or her commitment and accountability to his or her constituents." The plaintiffs here argue that by associating silence and dissenting views with white supremacy during the training, the school district imposed a similar punishment.

We decline to adopt the plaintiffs' broad reading of Gralike. Unlike the State in Gralike, the school district's presenters did not assign an epithet to the plaintiffs akin to a label next to a person's name on an election ballot. Instead, they chose to "stress that we are not calling you as an individual a white supremacist," while explaining their view that "certain actions or statements … can support that structural system of white supremacy." Nor did the training program "threaten a penalty" comparable to the "political damage" inflicted on candidates who disfavored term limits or remained silent on the issue in Gralike. The plaintiffs were required to endure a two-hour training program that they and others thought was misguided and offensive. But they were not forced to wear an arm-band classifying them as white supremacists or to suffer any comparable penalty.

The plaintiffs also argue that the defendants indirectly discouraged them from remaining silent or voicing dissenting views, both during the training sessions and in their private lives…. The plaintiffs rely primarily on the presenters' guidance to "Be Professional—Or be Asked to Leave with No Credit." They also refer to statements by the presenters telling attendees to "speak [their] truth," "turn and talk" to nearby colleagues, and share thoughts with the group.

We conclude that the plaintiffs' fear of punishment was too speculative to support a cognizable injury under the First Amendment. While the presenters warned that unprofessional conduct during the session could result in an attendee receiving no credit, they never said that expressing opposing views or refusing to speak was "unprofessional." The plaintiffs' reliance on Speech First, Inc. v. Cartwright (11th Cir. 2022), is thus misplaced. In Cartwright, the court concluded that a university's policy on "bias-related incidents" objectively chilled speech in part because the team responsible for investigating these "incidents" could refer students for discipline, even if the team could not directly punish students. Critically, the university stated that the team would investigate, monitor, and refer students for discipline because of the students' speech. Here, the school district's presenters did not state or insinuate that an employee's silence or dissenting views would be considered "unprofessional" and a basis to deny credit for attendance at the training.

To the contrary, the evidence shows that when the plaintiffs and others expressed views different from those of the school district, they received pushback from the trainers on the substance, but they were not asked to leave, and they were not called unprofessional. Attendees other than the plaintiffs largely remained silent and exhibited "very low participation." Yet the plaintiffs cite no evidence that anyone was disciplined, denied pay, or refused credit after attending the training. Therefore, the plaintiffs' subjective fear that dissent or silence would be considered "unprofessional" and grounds for denial of credit was too speculative to establish an Article III injury.

The plaintiffs' alleged fear that they would be punished for failing to advocate for the school district's view of "anti-racism" in their personal lives was speculative. They cite the district's definition of "anti-racism" as "the work of actively opposing racism by advocating for changes in political, economic, and social life." They refer to a greeting at the outset of training that referred to "this significant work for our own personal and professional development." But there is no evidence that the presenters purported to dictate what employees could say or do on their own time outside of work. Nor did the trainers communicate that the plaintiffs would be penalized for making particular statements or keeping quiet in their private lives.

Of course, the same conclusions would hold true if the district's training had aligned more closely with the views of the plaintiffs. Suppose the district's "anti-racism" training had emphasized that "[o]ur Constitution is color-blind," Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) (Harlan, J., dissenting), that persons should "not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character," Martin Luther King, Jr., I Have a Dream Speech (Aug. 28, 1963), and that "[t]he way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race." Parents Involved in Cmty. Schs. v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1 (2007). But suppose that some employees believed that practicing color-blindness perpetuated white supremacy, and that society is stratified in accordance with the "Oppression Matrix." So long as these employees, like [plaintiffs], were not punished or threatened with punishment for remaining silent or expressing disagreement with the district's program, they could not establish an injury from required attendance at a two-hour color-blind anti-racism training session.

The court also held that requiring plaintiffs to answer online questions, indicating the "correct" answer according to the course content, wasn't an unconstitutional speech compulsion:

[I]n this type of training module, an employee's "selection of credited responses on an online multiple-choice question reflects at most a belief about how to identify the question's credited response." … [A]public employer can require employees to demonstrate as part of their official duties that they understand the employer's training materials. See Altman v. Minn. Dep't of Corr. 3 (8th Cir. 2001) ("[A] public employer may decide to train its employees, it may establish the parameters of that training, and it may require employees to participate."); cf. Janus v. AFSCME (2018) ("Of course, if the speech in question is part of an employee's official duties, the employer may insist that the employee deliver any lawful message."). But we are aware of no authority holding that simply requiring a public employee to demonstrate verbally an understanding of the employer's training materials inflicts an injury under the First Amendment, so we decline to construe Henderson's completion of the modules as an injury in fact.

The post Eighth Circuit Grants Rehearing En Banc as to Whether "Equity Training" Requirement for Public Employees Violates First Amendment, … appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Speech to Idaho Minors Urging Them to Get Legal Out-of-State Abortions Protected by First Amendment, Even When …

From yesterday's decision in Matsumoto v. Labrador, written by Ninth Circuit Judge Margaret McKeown and joined by Judge John Owens:

This case concerns a unique legislative undertaking: an "abortion trafficking" statute. Idaho Code § 18-623. Idaho defines the crime of "abortion trafficking" as "procur[ing] an abortion" or "obtain[ing] an abortion-inducing drug" for an unemancipated minor by "recruiting, harboring, or transporting [a] pregnant minor" with the intent to conceal the abortion from the minor's parents or guardian. This provision appears to be the first post-Dobbs statute to criminalize the act of helping another person obtain an abortion, even if that abortion is legal in the state where it occurs….

[We conclude that] the statute's provision on "recruiting" violates the First Amendment by prohibiting "a substantial amount of protected speech relative to its plainly legitimate sweep." … [But we conclude that] the prohibition of "harboring and transporting" … do not violate Challengers' First Amendment rights. We also conclude that the statute is neither void for vagueness nor facially in violation of the First Amendment rights of association….

Before launching into an analysis of the statutory text, we note that this statute is unusual among trafficking statutes, despite its "abortion trafficking" title. There are two fundamental dissimilarities between Section 18-623 and traditional trafficking statutes. To begin, traditional human trafficking statutes typically apply to coercive conduct and/or the facilitation of universally illegal purposes. In contrast, Section 18-623 criminalizes non-coercive as well as coercive conduct for the procurement of legal abortions—for instance, performed in Oregon or Washington—as well as illegal ones. The term "trafficking," whether of humans or otherwise, is also usually defined with respect to an illegal trade with economic motive. In contrast, Section 18-623 does not contemplate any type of trade or economic motive….

[A.] Void-for-Vagueness Challenge

… Section 18-623, despite its awkward construction, does not fall afoul of the vagueness line. Certain conduct is either clearly proscribed by the statute, such as providing transportation and shelter to minors seeking abortions in other states; clearly not proscribed by the statute, such as soliciting donations to organizations that support pregnant minors seeking abortions; or, in the case of conduct that might be understood as "recruiting," is subject to an "imprecise but comprehensible normative standard."

The ordinary meaning of "recruiting," albeit broad, is sufficiently clear, such that we cannot say that Section 18-623 "specifie[s]" "no standard of conduct … at all." Even in a novel context, different from conventional "trafficking," the ordinary meaning of "recruiting" is plain. In determining vagueness, we look to the words of the statute, not the moniker that the state legislature gives the statute.

We see no inconsistency in treating "recruiting" as a comprehensible standard, even if that standard impermissibly sweeps in a broad swath of protected speech, as discussed below. A statute that is not constitutionally vague may still be overbroad under the First Amendment.

[B.] First Amendment Challenge—Right of Association

Section 18-623 does not limit Challengers' ability to solicit donations, require them to unmask their anonymous members, impinge on the anonymity of their donors, or inhibit their general advocacy of the right to abortion in Idaho or elsewhere. Idaho is not forcing anyone to refrain from supporting or joining these organizations. It is not requiring individuals or the organizations to join a group they otherwise would eschew. It does not limit their ability to provide information, support, guidance, and options counseling to pregnant adults in Idaho. Challengers' associational arguments do not provide an additional basis to enjoin Section 18-623 on First Amendment grounds….

[C.] First Amendment Challenge—Speech

[W]e construe the statute to cover abortion procurement for a minor in Idaho that involves recruiting or harboring or transporting, and we treat these alternatives separately….

[1.] "Harboring" and "Transporting"

There is no serious confusion regarding what conduct constitutes "harboring" or "transporting" within the meaning of Section 18-623. Dictionaries define "harbor" as giving "shelter" or "refuge" to someone, including those who might be evading law enforcement or who need protection. Meanwhile, "transport" denotes carrying or conveyance of something or someone from one place to another. Given these definitions, and the context of these terms within the statute ("procuring … by harboring or transporting"), the conduct covered by "harboring" and "transporting" is not expressive on its face. Even crediting that there may be some expression associated with or implied in harboring or transporting, we are not convinced that the bulk of "harboring" or "transporting" acts covered by the statute are expressive. {We offer no opinion on whether Challengers could succeed on an as-applied challenge to these provisions [under particular circumstances].

[2.] "Recruiting"

Because neither the "harboring" nor the "transporting" provision supports a facial First Amendment challenge to Section 18-623, this appeal turns on the meaning of the word "recruiting" within Section 18-623…. The ordinary meaning of the verb "recruit" is to seek to persuade, enlist, or induce someone to join an undertaking or organization, to participate in an endeavor, or to engage in a particular activity or event….

Idaho endeavors to limit the statute's scope by asserting simply that "providing information to minors" is not proscribed by Section 18-623. However, information—especially information trying to persuade a girl to have an abortion or regarding the provider, time, place, or cost of an available abortion—could satisfy the plain meaning of "recruit." And provision of that information to a minor in conjunction with procuring an abortion could well be a violation of Section 18-623 and subject an individual to criminal liability.

The statute contains the following limiting language: "the terms 'procure' and 'obtain' shall not include the providing of information regarding a health benefit plan." This narrow exclusion leaves wide open the fate of information not circumscribed by a "health benefit plan." For instance, Challenger Matsumoto would like to continue "provid[ing] advice on how pregnant people, including minors, can legally access [a]bortions," "provid[ing] information and options counseling to … pregnant minors, about abortion," and giving advice and support to organizations that assist pregnant minors who are survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault. The Indigenous Idaho Alliance would like to continue providing "pregnant people, including minors, with reproductive health care information, including information about abortion." The Northwest Abortion Access Fund would like to continue providing "emotional … and informational assistance" to pregnant minors. Any of these activities could arguably satisfy the plain meaning of "recruiting" and, coupled with "procuring" or "obtaining" an abortion, put individuals and organizations at risk of criminal penalties.

Apart from providing information, "recruiting" may also include subsidizing or fully funding an abortion—whether through donations or discounted services—by making the abortion more attractive (persuading) or more feasible (inducing). The Indigenous Alliance asserts that it may "provide financial assistance" for the "coordinat[ion of] the travel of pregnant people, including minors, from locations across the region, including Idaho, to and across state lines to access abortion." The Northwest Fund, too, wishes to continue providing "financial, logistical [and] practical assistance." Its work has involved "booking and paying for bus tickets, plane tickets, and ride shares"; "providing volunteers to drive patients to abortion appointments in states where abortion is legal"; and "provid[ing] food assistance, funding to abortion providers for their work, and lodging assistance." Similar activities might include offering a discount on medical procedures for under-resourced people, including minors, or setting up doctors' appointments for abortions and broadcasting the availability of those appointments to minors.

Like the parties, Amici express concerns that "recruiting" will encompass financial support and logistical assistance. They contemplate what Section 18-623 means to an individual who "financially supported … women who need help travelling out-of-state to obtain an abortion," as well as to advocates who assert a desire to continuing working "with people, including young people, to overcome the financial and logistical obstacles that prevent people from getting the abortions they need and want."

Legal advice, too, might constitute recruiting under Section 18-623, even if that advice persuades a minor to obtain a legal abortion. One organization, If/When/How: Lawyering for Reproductive Justice, "provides direct legal services … to ensure that young people have the legal rights and resources they need to make important decisions about their reproductive wellbeing. Through its national helpline, the organization provides legal information, advice, representation, and lawyer referrals to young people seeking access to abortion care."

Even expressions of persuasive encouragement might be prosecuted under the statute. Imagine an Idaho resident who lives near the border of Oregon and displays a bumper sticker that reads: "Legal abortions are okay, and they're right next door. Ask me about it!" A minor sees the sticker and, feeling desperate, approaches the driver to request a ride across state lines. "I need an abortion," the minor says, "and my parents can't know." The driver says: "I'm sorry, I can't drive you there. But, here, take this cash. That should cover the procedure." The minor takes the cash, finds a ride to Oregon with another minor, and gets a legal abortion with the money the driver provided.

Under Section 18-623, the driver might be prosecuted for "recruiting." The driver's expression invited contact, causing the minor to approach and find out how to get a legal abortion. The bumper sticker, and perhaps the offer of cash, arguably persuaded or even induced the minor to have the abortion. The cash also paid for, or "procured," the abortion. Thus, the driver procured an abortion for the minor, in part by recruiting. Under Section 18-623, the adult need only have "the intent to conceal an abortion" from the parents. No similar intent to conceal applies to "recruitment"; the bumper sticker, or a sign, or a pamphlet, can be out in the open for all to see and yet serve as a hook for prosecution.

Worryingly, the "recruiting" provision encompasses an adult's encouragement of a minor not only to obtain a legal abortion out-of-state, but also to obtain a legal abortion in Idaho under one of the few exceptions to the state's near-total abortion ban, such as pregnancy resulting from an act of rape or incest that was previously reported to law enforcement. That is, an adult concerned for the wellbeing of an underage victim of incest would be prohibited from counseling and then assisting that victim in obtaining an abortion without informing a parent—who may well be the perpetrator.

Some "recruiting" appears at first glance to be out of scope—namely, any "recruiting" that is not done in conjunction with procuring an abortion or obtaining an abortion-inducing drug for a minor. The statute does not criminalize "recruiting" alone, but rather "procuring" or "obtaining" by "recruiting." An adult merely distributing a pamphlet of information on states' laws regarding abortion, or displaying a pro-choice bumper sticker, would not fall within the scope of the statute. Both examples may be an effort to persuade a minor to consider an abortion, but in neither case did the adult procure an abortion for a minor. Even if the pamphleteer were stationed at the entrance of a high school, and a pregnant minor, upon seeing the information contained in the pamphlet, independently drove across the border to obtain an abortion, the pamphleteer would not have procured that abortion.

However, we note that these scenarios could be considered an "attempt" to procure an abortion for a minor by recruiting that minor without parental consent. If done in tandem with another adult who did procure an abortion, the above could be form of "aiding and abetting" such procurement.

With prosecutions for attempting or aiding and abetting procurement on the table, the reach of the statute could extend even further. For example, an attorney advising a minor about the minor's rights to obtain a legal abortion outside of Idaho and promising absolute confidentiality (including from the minor's parents), coupled with arrangements to procure an abortion, could be prosecuted for attempting or aiding and abetting a violation of Section 18-623. The same could be said of an employee of an advocacy organization counseling a minor about her healthcare options, providing the minor with the contact information of a partner organization in a neighboring state that can provide logistical or financial assistance in procuring or obtaining an abortion, and promising to keep the conversation a secret from the minor's parents.

These plain language applications of "procur[ing] … by recruiting" underscore that the statutory language covers a wide array of speech and conduct. Idaho's efforts to limit the reach of Section 18-623 are not consistent with the plain meaning of the statute. Ultimately, "[w]e may not uphold the statutes merely because the state promises to treat them as properly limited."

Having ascertained the broad scope of "recruiting," we next ask whether the speech or conduct swept into that scope is expressive and protected under the First Amendment. Speech is protected unless it falls within a narrow exception to First Amendment protection. Conduct, too, may be protected, if it evinces "an intent to convey a particularized message" and "in the surrounding circumstances the likelihood was great that the message would be understood by those who viewed it."

Encouragement, counseling, and emotional support are plainly protected speech under Supreme Court precedent, including when offered in the difficult context of deciding whether to have an abortion [citing cases protecting anti-abortion speech]. This protection includes promotion and urging of particular actions. Even if speech induces a particular course of action, the speech is protected as long as that action is not illegal. U.S. v. Hansen (2023) [a case that concluded that speech soliciting specific illegal action is constitutionally unprotected -EV]. "I think you should get a legal abortion in Washington," or "we believe in and fund legal abortions"—these, too, are protected expressions.

{Consider, for example, the statements of a representative from a crisis pregnancy center during the Senate committee hearing on Section 18-623. In her testimony in support of the bill, she described a scenario not unlike one that Challengers might face: A pregnant minor comes to the center, scared, perhaps afraid to tell her parents, and looking for guidance, and the representative provides that guidance, but only in support of continued pregnancy. Giving advice to a pregnant minor is legal and presumably protected expression in Idaho—even without informing the minor's parents and obtaining their consent—if that advice is directed toward advising that minor to carry her pregnancy to term. But under Section 18-623, advice arguably becomes illegal "recruitment" when it offers an abortion—critically, including a legal abortion in another state—as an option.}

Likewise, information related to the availability of abortions, education on reproductive health care options, and instruction as to how to access an abortion legally are also protected under Supreme Court precedent. Announcements related to the availability of abortions "involve the exercise of the freedom of communicating information and disseminating opinion." Bigelow v. Virginia (1975) (regarding an advertisement that stated: "Abortions are now legal in New York. There are no residency requirements"). A "purely factual" statement about a medical drug is also protected, so long as it is a statement of public interest. Information and instructions regarding the availability and means of procuring an abortion procedure or drug (likely including specifics, such as who the provider is, when and where the procedure would take place, or what a drug would cost) are thus squarely protected.

One facet of recruiting encompasses legal advice about the minor's rights. The First Amendment protects speech "advocating lawful means of vindicating legal rights," including "advising another that his legal rights have been infringed."

Public advocacy and education campaigns on issues of public interest are also protected political speech. This includes advocacy campaigns that encourage minors to consider the full range of available reproductive health care options.

Whatever the degree of their protection, none of these expressions lose that protection when expressed to minors. "[O]nly in relatively narrow and well-defined circumstances may government bar public dissemination of protected materials to [minors]." "Speech that is neither obscene as to youths nor subject to some other legitimate proscription cannot be suppressed solely to protect the young from ideas or images that a legislative body thinks unsuitable for them." The statute's mens rea requirement—"with the intent to conceal an abortion from the parents or guardian of a pregnant, unemancipated minor"—also does not delimit the First Amendment problems with Section 18-623. The Supreme Court has expressed its "doubts" that "punishing third parties for conveying protected speech to children just in case their parents disapprove of that speech is a proper governmental means of aiding parental authority." Brown v. Ent. Merch. Ass'n (2011).

We now come to Idaho's contention that the expressive speech and conduct covered by "recruiting," otherwise protected by the First Amendment, is rendered unprotected because it is speech integral to criminal conduct. For that exception to apply, speech must be "used as an integral part of conduct in violation of a valid criminal statute." Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice Co. (1949). It is true that "recruitment" under Section 18-623 occasionally may be "speech integral to criminal conduct," but those circumstances reflect a small subset of the protected speech covered within recruitment.

Idaho is correct that recruiting an Idaho minor to get an illegal abortion in Idaho qualifies as speech integral to criminal conduct. See, e.g., Idaho Code § 18-622 (criminalizing nearly all abortions in Idaho). In recognition of the Supreme Court's decision in Dobbs, we assume without deciding that Section 18-622 is a valid criminal statute. Thus, "recruiting" under Section 18-623, to the extent that it induces a minor to violate Section 18-622 via the adult's procurement of abortion for that minor, would be speech integral to criminal conduct.

But Section 18-623 goes well beyond the strictures of Section 18-622, and indeed beyond Idaho's borders. The statute explicitly reaches procurement of abortions that are legal where they are performed: "It shall not be an affirmative defense to a prosecution … that the abortion provider or the abortion-inducing drug provider is located in another state."

Idaho's asserted police powers do not properly extend to abortions legally performed outside of Idaho. As Justice Blackmun wrote:

A State does not acquire power or supervision over the internal affairs of another State merely because the welfare and health of its own citizens may be affected when they travel to that State. It may seek to disseminate information so as to enable its citizens to make better informed decisions when they leave. But it may not, under the guise of exercising internal police powers, bar a citizen of another State from disseminating information about an activity that is legal in that State.

Bigelow. To qualify as speech "integral to unlawful conduct," the speech must be done in furtherance of the commission of an underlying criminal offense. Hansen. A legal abortion—whether performed in Idaho, under an exception to Section 18-622, or in another state—is not a criminal offense and so cannot serve as the "underlying offense" to render otherwise protected speech unprotected.

Can the abortion trafficking statute manufacture both the "underlying offense" and the exception to otherwise protected speech? Idaho cites United States v. Dhingra as support for the proposition that it can. In Dhingra, we interpreted a statute as regulating only unprotected speech when it regulated "the targeted inducement of minors for illegal sexual activity"—even if speech was used as the "vehicle" for "ensnar[ing] the victim." Both that opinion and the statute in question referenced separate, non-expressive activity that was illegal, independent of the inducement thereof. See 18 U.S.C. § 2422(b) (criminalizing inducement of others' engagement "in prostitution or any sexual activity for which any person can be charged with a criminal offense"). The Supreme Court addressed a similar point in United States v. Williams: speech may be criminalized where it is "intended to induce or commence illegal activities"—that is, independent activities that are illegal.

Under this statute, a prosecution may be brought against someone who procured an abortion for a minor by recruiting, but not harboring or transporting, that minor. In the context of a legal abortion, recruiting may be the only hook for potential prosecution under Idaho Code Section 18-623. In a case where the adult procures a legal abortion by recruiting the minor, but not by harboring or transporting the minor, there is no underlying offense but the recruitment itself. To the extent that such recruitment is protected speech, it cannot serve to self-invalidate. Labeling protected speech as criminal speech cannot, by itself, make that speech integral to criminal conduct….

As discussed above, "recruiting" has broad contours that overlap extensively with the First Amendment. It sweeps in a large swath of expressive activities—from encouragement, counseling, and emotional support; to education about available medical services and reproductive health care; to public advocacy promoting abortion care and abortion access. It is not difficult to conclude from these examples that the statute encompasses, and may realistically be applied to, a substantial amount of protected speech. Whether that protected speech is assessed against all activities covered by the individual "recruiting" component, or benchmarked against the statute as a whole, it is substantial in proportion. We therefore hold that the statute is unconstitutionally overbroad….

Judge Carlos Bea concurred in the judgment in part and dissented in part, on standing and redressability grounds.

The post Speech to Idaho Minors Urging Them to Get Legal Out-of-State Abortions Protected by First Amendment, Even When … appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Court Rejects Lawsuit Against Nancy Grace Over True-Crime Podcast Related to Prosecution for Rape of Madison Brooks

From Carver v. Grace, decided today by Judge Carl Barber (E.D. La.):

This defamation case derives from the alleged rape and tragic death of an LSU student, Madison Brooks, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. After a heavy night of drinking, Madison Brooks left a Baton Rouge bar with Plaintiffs Casen Carver and Everett Lee and their two male companions, Kaivon Washington and Desmond Carter.

Less than an hour later, Madison Brooks was dropped off at Pelican Lakes Neighborhood, the entrance of which is off Burbank Drive. Madison Brooks was later hit and killed by a motor vehicle on Burbank Drive. Kaivon Washington and Desmond Carter were indicted for raping Madison Brooks in the backseat of the car. Plaintiff Casen Carver, the driver, was indicted for first-degree rape, third-degree rape, and video voyeurism Plaintiff Everett Lee rode in the passenger seat and remains under investigation….

Plaintiffs allege Nancy Grace and iHeartMedia made defamatory statements by … on (1) [Nancy Grace's] YouTube program titled "Nancy Grace Analyzes Defense Reaction to Damning Video of Attack on LSU Coed" ("Crime Online Show") and (2) on an episode of Nancy Grace's podcast, distributed by iHeartMedia, Crime Stories with Nancy Grace, titled "Haunting Video of LSU Beauty Madi Brooks Who Dies After 3 Men Allegedly Sex Assault" (Crime Stories Podcast")….

Considering the statements as whole in the context in which they were made, the Court finds Nancy Grace and iHeartMedia's statements are not actionable. The statements are not defamatory because they are either not "of and concerning" the Plaintiffs; substantially true; Nancy Grace's opinion; and/or based on statements of law enforcement officials….

[Defendants] first allege the following statement by Nancy Grace is not actionable in defamation:

There's no way, this little girl, consented to have sex in the backseat, of a car, while someone is videoing, and laughing, and she's saying no, and she's drunk, and they find I believe it's anal tears and bruising and they find the defendants[2] DNA on her person, is it so hard for you to believe Ferrintino that the perps withdrew before they ejaculated, I mean there's really no nice way to explain that, but is that so hard for anybody to believe because I find it very easy to believe.

[2] Note: Plaintiffs' petition does not use an apostrophe 's' after defendant, thus making it 'defendants DNA'; whereas the Defendants' motion and attached transcript uses an apostrophe 's' therefore, making it 'defendant's DNA.'

… After considering the statement in its context, the Court does not find this statement defamatory. First, it is not 'of and concerning' the Defendants. This statement made by Nancy Grace was only five minutes and twenty-two seconds into the YouTube video. At the time of this statement in the program, Nancy Grace has neither shown a picture of Plaintiff Casen Carver nor of Plaintiff Everett Lee. Even more so, Nancy Grace has not stated Plaintiffs' names as this point. In fact, Nancy Grace started this program off by referring to the "rape Defendants;" thereby indicating that she is analyzing the defense of the "rape Defendants" in the criminal action associated with Madison Brooks' death. Plaintiff Everett Lee is not a "rape Defendant" nor a defendant in the criminal action. Moreover, Nancy Grace did not misidentify or improperly quote either of the Plaintiffs during the program. Nancy Grace also showed photos of Kaivon Washington and Desmond Carter. Thus, Plaintiffs attempt to argue that this statement is 'of and concerning' the Plaintiffs because of mere photographs shown or names stated is unpersuasive.

Regarding the statement itself, the Court finds that this is not 'of and concerning' the Plaintiffs because the first half of the statement—"There's no way, this little girl, consented to have sex in the backseat, of a car, while someone is videoing, and laughing, and she's saying no, and she's drunk, and they find I believe it's anal tears and bruising and"—is not "of and concerning" the Plaintiffs, but concerns Madison Brooks. Also, Nancy Grace, as a former prosecutor turned journalist, is stating her opinion as to her belief why Madison Brooks did not consent. This opinion was based on disclosed facts by the Plaintiff Carver's Affidavit for Arrest Warrant that Madison Brooks was intoxicated and by a news media reporter that "someone [was] videotaping and laughing." Nancy Grace uses phrases like "There's no way" and "I believe"; therefore, indicating it is her opinion. Thus, an ordinary viewer of reasonable intelligence and sensibilities hearing the statement would conclude that Nancy is asserting her opinion.

As for the second half of statement, Plaintiffs "cherry pick" at Nancy Grace's use of the term "defendants DNA" and "perps" and "they ejaculated" arguing that Defendants "clearly" were referring to Plaintiffs. The Court disagrees. Shortly after the statement was made, Nancy Grace clearly identifies that the DNA found on Madison Brooks' person was Kavion Washington. Nancy Grace referred to a WBRZ article. Put in context, this statement is part of a question to guest attorney Jarrett Ferrintino— "I mean, is it that hard for you to believe, Ferentino, that the perps withdrew and then ejaculated?" … Therefore, given the context of the statement, the Court finds that it is not "of and concerning" the Plaintiffs.

Second, Defendants move to dismiss Plaintiffs' claims that the statement in paragraphs 78 and 98 of the petition is actionable in defamation— "In the middle of the night, the rain, heavy traffic flying by, they put her out the car and bam, she gets run over, and dies, after she gets raped." Plaintiffs focus on the phrase "they put her out of the car" and argue that this is defamatory because "any reasonable watcher or listener would interpret this statement to mean that Plaintiffs kicked Ms. Brooks out of the vehicle in the middle of a busy highway…" Additionally, Plaintiffs argue that during the episode "Casen Carver's name is mentioned 7 times … and Everett Lee's name was mentioned twice" and that Defendants showed actual images of both Plaintiffs. Thus, "this is certainly "of and concerning" plaintiffs."

After reviewing the programs at issue, the Court finds this is not defamatory. Nancy Grace made this statement approximately seven minutes into the program. Like the previous statement at issue, neither Plaintiffs' pictures were shown, nor were their named yet mentioned at the time Nancy Grace made this statement. Again, Nancy Grace started the Crime Show Online by referring to the "rape Defendants;" thereby indicating that she is analyzing the defense of the "rape Defendants" in the criminal action associated with Madison Brooks' death. Plaintiff Everett Lee is not a "rape Defendant" nor a defendant in the criminal action. Moreover, Nancy Grace did not misidentify or improperly quote either of the Plaintiffs during the program. Nancy Grace also showed photos of Kaivon Washington and Desmond Carter. Thus, Plaintiffs attempt to argue that this statement is 'of and concerning' the Plaintiffs because of mere photographs shown or names stated is unpersuasive. It otherwise would be a "chilling effect" on exercise the First Amendment, not allowing Nancy Grace "breathing space." Since the Court finds that the statement is not "of and concerning" the Plaintiffs, it does not address the parties' other arguments, since if one of the elements for a defamation claim is absent, the cause of action fails.

Third, Defendants move to dismiss Plaintiffs' claims that the statement in paragraphs 79 and 99 of the petition as not actionable in defamation. The statement is as follows:

They're really lucky, and I don't get it, that they haven't been charged with felony murder, because she is dead, while a felony was ensuing, they raped her, according to the state it's got to be proven in a court of law of course, then put her out of the car on a busy freeway which is abandoned and malignant heart, which is a theory of murder.

… The Court finds this statement is not defamatory per se. Accusations of a crime are considered defamatory per se in Louisiana. Given the context, the statement is substantially true and Nancy Grace's opinion and not an accusation of a crime. In denying Plaintiffs' Motion to Remand, the Court previously considered whether a similar statement was defamatory. The Court considered whether Defendant Ashley Baustert's statement suggesting, according to Plaintiffs, that "they" caused Madison Brooks' death by dropping her off "on Burbank Drive" was defamatory. The Court found the "gist" or "sting" of Defendant Baustert's statement was the fact that the Plaintiffs dropped off Madison Brooks alone on a road at night when she was highly intoxicated without a cell phone, not that she was dropped off on Burbank Drive. The Court reasoned that the Plaintiffs acknowledged that Madison Brooks was alone and intoxicated when they dropped her off and do not dispute that she was left without a cell phone in their petition.

The Court finds its prior reasoning applicable here. Nancy Grace is reporting on a crime, a matter of public interest. This inaccuracy of the location of where Madison Brooks exited the vehicle should not lend itself to be actionable as defamation, because it is not a significant variation from the truth. Plaintiffs dropped off Madison Brooks in the vicinity of Burbank Drive, which is the "gist" of Nancy Grace statement; and thus substantially true.

Additionally, the Court finds that this statement is Nancy Grace's opinion. The Court finds that a reasonable viewer of the program would conclude "They're really lucky, and I don't get it, that they haven't been charged with felony murder…" to be Nancy Grace's opinion because she expresses her personal feelings or a critique of the legal system. This is not a direct accusation as she states "it's got to be proven in a court of law of course." The phrase "I don't get it" indicates Nancy Grace's confusion to understand why the Plaintiffs not being charged with felony murder occurred. Her use of the term "lucky" is also subjective and appears to reflect her perception that criminal defendants are fortunate given their circumstances.

Fourth, Defendants move to dismiss Plaintiffs' claims that the following statement in paragraphs 82 and 103 of the petition is actionable in defamation:

These guys should be thanking their lucky stars they're not charged with murder, not sure why they aren't charged with murder, but yet they are actually complaining.

The Court finds this statement is Nancy Grace's opinion as she is first expressing her personal perception that the criminal defendants are fortunate; and second, she is critiquing the state's prosecutorial discretion. This statement is neither true nor false and is purely subjective. Nancy Grace's opinion was based on established facts from police reports and other media outlets. Both the Fifth Circuit and Louisiana state courts have protected expressions of "strong" opinions about persons connected to criminal activity, even if those persons have not been charged with crimes.

Fifth, Defendants move to dismiss the Plaintiffs' claims that the following statement in paragraphs 83 and 104 is actionable in defamation:

Sometimes you have to go to hell to get the witness to put the devil in jail. I really believe if you tried these four together, put them on the same pot to stew, there would be a conviction, on every one of them, because they're in it together and the video, truly the video, they thought was such a good idea, that is the nail in the coffin.

The Court finds this statement is Nancy Grace's subjective opinion. First, Nancy Grace's signals she is offering opinion rather than asserting facts because of her use of figurative and hyperbolic language such as "go to hell," "put the devil jail" and "nail in the coffin." Although Nancy Grace references "conviction" and the involvement of "four" individuals, she does not provide factual allegations that can be objectively proven true or false. Additionally, the statement hinges on a hypothetical scenario, "if you tried these four together…" and then Nancy Grace speculates the outcome, "there would be a conviction." Thus, a reasonable viewer of the Crime Online Show would conclude that Nancy Grace is offering her opinion, not accusing Plaintiff "Lee of rape" as the Plaintiffs suggests.

Sixth, Defendants move to dismiss Plaintiffs' claims that the following statement in paragraphs 14, 84, and 105 of the petition is actionable in defamation:

[T]hey gave very detailed statements about what happened to Madi, in fact, the ones in the front seat rotating into the back seat so they can also assault her.

The falsity of the reference to "the ones in the front seat rotating into the back seat" is not disputed. However, the Court must view Nancy Grace's statement in the context of the Crime Stories Podcast. Shortly following this statement, Nancy Grace directs the listener to listen to a voiceover, which clearly states:

[Madison Brooks was] either raped or ha[d] consensual sex with two of these young men. They take turns. One gets out of the vehicle while the other one has sex with her or rapes her, then they swap over. While this happens, [Plaintiff] Casen Carver, the driver, and the oldest defendant, his name is [Plaintiff] Everett Lee, they're in the two front seats of this vehicle.

Thus, the voiceover amends Nancy Grace's statement to make it clear to the listener that Plaintiffs did not rotate from the front seat to the back seat. Considering the entirety of the Crime Stories Podcasts, the context in which the allegedly defamatory statement was used, including the amendment made by the voice over, the Court finds, when considered as a whole, that the statement does not make a false and defamatory statement because it is substantially true. The "gist" of the story was that two people took turns assaulting Madison Brooks when one person assaulted her in the back seat and exited the vehicle and the second person "rotated" or "swapped" into the back seat. Additionally, as the voiceover amends the statement, a reasonable listener to the Crime Stories Podcast would know that Plaintiffs Casen Carver and Everett Lee stayed in front seat while their two companions rotated out of the back seat, assaulting Madison Brooks.

Seventh and eighth, Defendants move to dismiss Plaintiffs' claims that the statements, "it gives me no joy in saying any of the things I'm saying tonight, but they are true" in paragraphs 86 and 106; and "may he rot in hell" in paragraph 85 of the petition are defamatory. With regards to the statement in paragraphs 86 and 106, the Plaintiffs argue that "[t]he purpose of this statement … is to demonstrate Defendant Grace's actual malice" because Grace had knowledge that Madison Brooks was "dropped off in a neighborhood, yet she maliciously, in reckless disregard for the truth, repeatedly lied and levied additional charges for murder" and therefore, Plaintiffs argue "[t]his proves that all statements pertaining to 'putting Ms. Brooks out of the car' and a 'busy highway' are ALL in reckless disregard of the truth. Regarding the statement "may he rot in hell," Plaintiffs argue the statement shows Defendant Grace's actual malice. Since the Plaintiffs do not argue that these statements are defamatory in and of themselves, the Court finds these statements are not actionable in defamation.

Additionally, as discussed above, the alleged defamatory statements have failed for other reasons and therefore the Court does not discuss the element of actual malice….

The post Court Rejects Lawsuit Against Nancy Grace Over True-Crime Podcast Related to Prosecution for Rape of Madison Brooks appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers