Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 201

December 24, 2024

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: December 24, 1798

12/24/1798: The Virginia Resolution, authored by James Madison, is published.

James Madison

James MadisonThe post Today in Supreme Court History: December 24, 1798 appeared first on Reason.com.

December 23, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Trump Media & Technology Group Loses Lawsuit Against Washington Post Over Story About Trump Social Deal

From Judge Tom Barber (M.D. Fla.) today in Trump Media & Tech. Group Corp. v. WP Co. LLC:

This lawsuit for defamation by Plaintiff Trump Media & Technology Group Corp. ("TMTG") against Defendant WP Company LLC (the "Post") arises from an article titled "Trust linked to porn-friendly bank could gain a stake in Trump's Truth Social," published by the Post on May 13, 2023, and circulated on Twitter (now known as "X") by Post personnel. The article described events related to a contemplated merger between TMTG and a special purpose acquisition company ("SPAC") known as Digital World Acquisition Corp. ("DWAC") as part of taking TMTG's "Truth Social" business public.

The article noted there had been a delay in obtaining SEC approval for the merger, which supporters of former President Donald Trump and TMTG attributed to political bias. The article offered a "possible" alternative explanation: concerns by the SEC and other regulators regarding a loan obtained by TMTG, the identity of the lender, and whether the loan had been properly disclosed by TMTG and/or DWAC to DWAC's shareholders or the SEC. The article cited various sources for its story, including "internal documents a company whistleblower has shared with federal investigators and [the Post]," as well as statements expressly attributed to the whistleblower, former TMTG officer Will Wilkerson.

The article related that in late 2021, with the proposed merger "frozen" and TMTG concerned about paying its bills, then-DWAC president Patrick Orlando announced he had arranged for an $8 million loan from an entity known as "ES Family Trust." According to the article, the loan was part of a deal in which TMTG would receive the loan and, in exchange, ES Family Trust would acquire an equity interest in the public entity to be formed from the merger of TMTG and DWAC. This loan-for- stock deal was reflected, according to the article, in a convertible promissory note, although the article acknowledged that the only copy of the note the Post had been able to locate was unsigned.

The article reported that some of the funds were wired by another entity, Paxum Bank, which had ties to ES Family Trust and to the adult film industry. Also, according to the article, TMTG paid a finder's fee of $240,000 in connection with the loan to Entoro Securities, a Texas entity of which Orlando was a managing director. Although the article did not refer to a specific document evidencing the payment, it pointed to a broker agreement regarding the fee and an invoice for payment from Entoro.

The article stated that neither the loan-for-stock deal nor the finder's fee had been disclosed to shareholders of DWAC or the SEC. It further reported the opinion of Michael Ohlrogge, a New York University law professor who studies SPACs, that these matters could affect the value of the shares and should have been disclosed. The article also noted that the British journal The Guardian had earlier reported that federal prosecutors in New York were investigating whether TMTG had violated money laundering statutes in connection with the loan, and that TMTG Chief Executive Officer Devin Nunes had filed a lawsuit against Wilkerson and others (including The Guardian) asserting that the Guardian story was "fabricated." …

TMTG does not challenge the accuracy of the bulk of the story set forth in the Post's article, including the assertions that TMTG borrowed $8 million from an entity or entities with connections to the adult film industry, that the loan deal involved a pledge of stock in the company to be formed by the merger, and that some TMTG executives were concerned about the lack of information regarding the lender. TMTG's defamation claims now center on the Post's statements regarding the disclosure of the loan and the finder's fee to the SEC and investors….

The court concluded that the allegations were substantially true, plus that TMTG in any event didn't adequately allege "actual malice" (i.e., knowing or reckless falsehood on the Post's part):

Loan Statements

The first statement TMTG challenges is the following, taken from the text of the Post's May 13, 2023, article:

[T]he role ES Family Trust would assume in Trump Media and Technology Group has never been officially disclosed to the Securities and Exchange Commission ["SEC"] or to shareholders in Digital World Acquisition ["DWAC"], the special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, that has proposed merging with Trump's company[.]

… The Court agrees with the Post that these allegations fail to plead either falsity or actual malice. TMTG's allegation that disclosure of the involvement of ES Family Trust was not required does not suggest the falsity of the Post's assertion that no disclosure was made. TMTG argues, however, that the first Loan Statement falsely implied that disclosure of ES Family Trust's involvement was required. Assuming the statement could be reasonably read to imply that requirement, and further assuming no such requirement exists, TMTG as a public figure must allege actual malice by setting forth "facts sufficient to give rise to a reasonable inference that the false statement was made 'with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.'" …

TMTG alleges no facts supporting the proposition that the Post acted with actual malice in publishing the statement. TMTG's conclusory allegation that the Post knew disclosure of ES Family Trust was not required based on the Post's "consultation with supposed experts" is belied by Ohlrogge's opinions quoted in the article. Based on those opinions, the Post reasonably would have believed that disclosure was required, and TMTG's amended complaint contains no facts plausibly suggesting the Post was aware of contrary expert or other authority from which it would have known Ohlrogge's opinions were wrong or had serious doubts on that score.

{TMTG's responsive memorandum also refers to the "SEC's declaration of effectiveness of a subsequent registration statement," but this is not mentioned in the amended complaint and TMTG offers no explanation how it supports a contention that disclosure of ES Family Trust was not required or that the Post knew it was not required when it published the article.

TMTG attempts to cast doubt on Professor Ohlrogge's reliability by citing "recent" appearances by Ohlrogge on "left wing" media sites such as CNN, NBC, the New York Times, and the BBC. The Court rejects this argument because TMTG offers no specific information suggesting that any of these "recent" appearances would have been relevant to the Post's reliance on Ohlrogge when it published the article. Moreover, the amended complaint contains no allegations regarding Ohlrogge or his reliability, only a generic reference to the Post's "consultation with supposed experts."}

Equally insufficient are TMTG's allegations that the Post "knew" that disclosure of ES Family Trust was not required based on the absence of any disclosure of other lenders in DWAC's public filings. The article did not assert that TMTG or DWAC should have disclosed the ES Family Trust loan because disclosure of lenders is generally required. It reported Ohlrogge's opinion that disclosure was required in this instance due to issues relating to this specific loan. Accordingly, the lack of disclosure of other lenders in DWAC's filings is irrelevant.

Finally, TMTG's attempt to allege a circumstantial case for actual malice with respect to this and the other challenged statements likewise falls short. TMTG alleges, for example, that Will Wilkerson, a key source relied on by the Post, had been "terminated for cause" and "ousted" from TMTG and that "bad blood" existed between Wilkerson and TMTG. TMTG, however, offers no further details as to Wilkerson's departure from TMTG or his attitude toward the company. Reliance on a potentially biased source does not by itself establish actual malice. The article described Wilkerson as a "former executive" and a whistleblower who had shared information with government authorities as well as the Post. The fact that Wilkerson—an insider positioned to provide accurate information and supporting documents to the Post—was to some unspecified extent hostile to TMTG does not, without more, support an inference that he gave vent to that hostility by fabricating facts regarding the loan.

Further undermining any inference of actual malice, the article reflected the Post's reliance on sources apart from Wilkerson, including DWAC's public filings and other documents, as well as the opinions of Professor Ohlrogge. The article also noted that the Post had reached out to TMTG for comment before publication. Although TMTG did not respond, the article reported TMTG's criticism of a previous Post story as based on "discredited hit pieces, defamatory allegations and false statistics." … [T]here are no allegations showing that the statements in the article were inherently improbable, that the Post actually entertained doubts about the reliability of Wilkerson, or that the Post's investigation was grossly inadequate under the circumstances. Nor do the allegations suggest that the Post "purposefully avoided further investigation with the intent to avoid the truth.

TMTG argues that it may rely on the "sum total" of proper inferences to allege a circumstantial case for actual malice. While this is correct as a general proposition, TMTG's allegations, even taken collectively, do not support a reasonable inference the Post acted with actual malice. TMTG alleges, for example, that the Post harbored ill- will, bias, and "antipathy," and had engaged in a years-long crusade against TMTG characterized by "willful concealment of relevant information" and "re-publication of dubious and unverified accusations of illegal or untoward actions by TMTG." But TMTG alleges no specifics or factual support for these conclusions, just a series of negative headlines from previous Post articles. TMTG alleges that the Post's conduct departed from its code of ethics and professional standards, but offers no specifics as to what standards were breached or how. Controlling case law holds that conclusory allegations of this type are insufficient to support an inference of malice.

Finally, the amended complaint points to the fact that TMTG's CEO Devin Nunes filed a lawsuit (later dismissed) against The Guardian alleging that statements in the Guardian article, some of which the Post reported, were false. TMTG does not allege the Nunes lawsuit presented specific information that would have caused the Post to doubt the accuracy of statements made in its article. As the Court noted in its previous dismissal order, the Post's awareness of this lawsuit challenging the Guardian article is not necessarily probative of actual malice on the part of the Post….

The second Loan Statement appears in a tweet republishing the Post's May 13, 2023, article:

Trump's media company took out an $8 million loan in exchange for stock, but no one told the SEC[.]

The amended complaint alleges this statement was false, and the Post knew it was false, for the same reasons it alleged as to the first Loan Statement. Accordingly, for the same reasons discussed above, TMTG fails to allege falsity or actual malice as to the second Loan Statement as well.

TMTG's responsive memorandum argues the second Loan Statement was false because DWAC's public filings disclosed TMTG's debt in the aggregate and thereby disclosed "the loan." The Court rejects this argument. First, this is not the basis for falsity or actual malice alleged in the amended complaint. The Court's prior dismissal order directed TMTG to allege in its complaint in what respect each challenged statement was false, what information showed it was false, and why the Post would have been aware of that information. The Court will not allow TMTG to sustain its complaint based on different, unpleaded allegations set forth in its responsive memorandum. Second, TMTG offers no explanation why disclosure of its aggregate "debt" equates to disclosure of "the loan," particularly in the context of an article that addressed concerns about the circumstances surrounding a particular loan, not TMTG's "debt" or "convertible notes" in general. Accordingly, TMTG has failed to allege facts showing the second Loan Statement was false and that it was made with actual malice, as required to allege a claim for defamation.

The third of the challenged Loan Statements is the following, also in a tweet circulating the article:

Trump Media: this time they borrowed money from a bank best known for servicing the adult entertainment [sic], pledged a stake in the company for the loan and didn't tell the SEC.

For the same reasons discussed above as to the first and second Loan Statements, TMTG fails to allege falsity or actual malice, and its defamation claim therefore fails to the extent it is based on this statement.

Finder's Fee Statements

The statements TMTG challenges relating to the finder's fee remain the same as in the original complaint. The first Finder's Fee Statement is:

The companies also have not disclosed to shareholders or the SEC that Trump Media paid a $240,000 finder's fee for helping to arrange the $8 million loan deal with ES Family Trust[.]

The amended complaint asserts this statement was false because no fee was paid, and therefore there was no failure to disclose a payment. The amended complaint, however, does not challenge the article's assertion that there was an agreement to pay the fee. The Post accordingly argues that the defamatory "sting" of this statement would be the same whether the undisclosed finder's fee was actually paid or merely agreed to. Therefore, the Post argues, its statement was substantially true.

The Court agrees. "[U]nder the substantial truth doctrine, a statement does not have to be perfectly accurate if the 'gist' or the 'sting' of the statement is true."

A statement is considered false only where it is "substantially and materially false," that is, where the statement "would have a different effect on the mind of the reader from that which the pleaded truth would have produced….

TMTG does not deny there was an agreement to pay the fee to an affiliate of Orlando nor does it contend that the agreement was disclosed. Instead, it argues that a statement that payment was made and not disclosed "arguably implies fraud," whereas a statement merely asserting that "there was an agreement reached" does not imply fraud. Thus, TMTG argues, the defamatory sting of the two statements is different.

This argument is unpersuasive. As reflected in Ohlrogge's opinions reported in the article, the potential impropriety concerning the undisclosed finder's fee—and therefore the defamatory "sting" of the article—related to the potential conflict of interest involved when Orlando, an insider, arranged a payment to a company in which he had a financial interest. That conflict of interest would have existed whether TMTG merely undertook an undisclosed obligation to pay the fee to Orlando's company, or actually paid the fee. In the context of the entire article, then, whether the fee was paid, as the Post reported, or whether there was merely an agreement to pay the fee, the effect on the mind of a reader would be the same. Accordingly, the Post's statement was substantially true, even if incorrect on the issue of actual payment….

Even if the statement were not substantially true, the defamation claim based on the first Finder's Fee Statement also fails because TMTG does not allege facts showing actual malice….

The second Finder's Fee Statement is:

[T]he recipient of that fee was an outside brokerage associated with Patrick Orlando, then Digital World's CEO[.]

This statement simply adds a detail to the first statement by identifying the recipient of the payment. The Court's analysis of this statement is therefore the same as for the first statement….

The third Finder's Fee Statement is:

Orlando's finder's fee could affect the value of the shares.

TMTG's allegations as to falsity and actual malice in the amended complaint relate only to the first two Finder's Fee Statements. Neither the amended complaint nor TMTG's responsive memorandum offers anything specific to show the third statement was false or was published by the Post with actual malice and, as set forth above, TMTG has failed to plead facts making out a circumstantial case for actual malice. Accordingly, the amended complaint fails to state a claim for relief based on the third Finder's Fee Statement.

Carol J. Locicero and Linda Riedemann Norbut (Thomas & LoCicero, PL) and Nicholas G. Gamse and Thomas G. Hentoff (Williams & Connolly LLP) represent defendant.

The post Trump Media & Technology Group Loses Lawsuit Against Washington Post Over Story About Trump Social Deal appeared first on Reason.com.

[Orin S. Kerr] New Cert Petition on Emergency Entry: What Was the Common Law Rule?

A cert petition at the Supreme Court in on the Fourth Amendment standards for entry into a home to help people in an emergency. The question presented:

Whether law enforcement may enter a home without a search warrant based on less than probable cause that an emergency is occurring, or whether the emergency-aid exception requires probable cause.

The petition does not address the original public meaning of the Fourth Amendment, or the common law rules on this issue. But this is one area where there are common law authorities on the question, and they seem pretty home-protective. Given the Supreme Court's increased interest in originalism, I thought I might blog about what the established rule was for this issue at the time of the adoption of the Fourth Amendment, which presumably would inform what would have been understood as an unreasonable search and seizure.

Let's start with what was perhaps the best treatise on common law rules of criminal procedure, William Hawkins, Pleas of the Crown (1787 ed). Here's how Hawkins summarizes the rule:

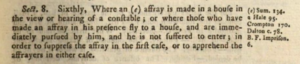

Here Hawkins states the rule as allowing entry when the "affray" (somewhat a term of art in the 18th century, but basically meaning a really big fight) is made in the constable's "view or hearing." It's not just that the constable has heard about the fight. He needs to see it or hear it. If he sees it or hears it, he can enter the home to "suppress the affray," that is, break up the fight.

What makes Hawkins particularly helpful as a treatise writer is that he cites sources. On the side note, he cites five sources. Let's take a look at them.

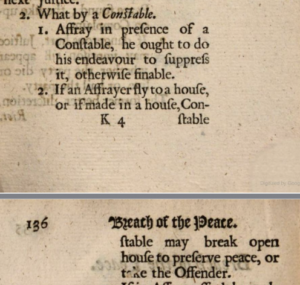

The first source is "Sum. 134-35." That refers to Matthew Hale's short volume, Pleas of the Crown: or, a Methodical summary of the principal matters relating to that subject, from 1678. The pincite is to Hale's discussion on the law of affrays, and he states the rule about the power of constables as follows:

Hale's short volume is less clear on the standard of entry. The constable ought to break up a fight in his presence (somewhere outside, one assumes) but there's nothing specific about what if the fight is ongoing in a house; does the constable need to see or hear the fight, as Hawkins is saying later on?

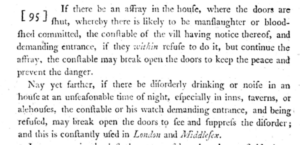

Hawkins next cited "2 Hale 95." That's a cite to Volume 2 of Hale's more developed and influential treatise, Historia Placitorum Coronæ, the 1736 edition of which contains the following at page 95:

In this volume, Hale talks of two different situations. First, if there's an affray in the house, and "there is likely to be manslaughter or bloodshed committed," the constable can demand entrance, and if no one lets him in but the fight is still ongoing, he can break in. Second, if there's a lot of noise going on at night, he can basically do the same.

Hawkins also cites "Crompton 170," which I assume refers to George Crompton's Practice Common-placed Or, The Rules & Cases of Practice in the Courts of King's Bench & Common Pleas, although at least on a quick look I can't find the relevant discussion. It may be that, since Hawkins wrote his treatise in 1719, that the pagination of Crompton was different from the later editions I find on Google books. Or maybe that's the wrong Crompton treatise? Not sure. I'll have to look into that more later.

The next Hawkins cite is to "Dalton c.78," which is to Chapter 78 of Michael Dalton's Country Justice, the chapter on jails, although it seems to be mostly about who pays for setting up a jail (a big deal in an era where there was no state-provided jail). That's perhaps relevant to the second common law rule in that Hawkins paragraph, about hot pursuit searches, but it doesn't seem relevant to the rules about emergency entry.

Finally, there's a citation to "B.P. Imprison. 6." I'm not sure what that is, but I wonder if it's to a Parlimentiary writ of the era, "B.P." standing for ""Brevia Parliamentaria," or "Before Parliament." Perhaps a writ relating to imprisonment powers, akin to the citation to Dalton above? I'm not sure.

Anyway, combining the Hawkins rule from his Pleas of the Crown with the rule from Hale's Historia Placitorum Coronæ, I take the common law authorities to suggest some significant certainty about whether the "affray" is happening inside the house before the constable can enter. Hawkins says the constable has to hear or see the big fight. Hale says it needs to be "likely" that there will be manslaughter or bloodshed, something that to me sounds more suggestive of a probable cause standard. Hale's mention of noise coning from the house seems consistent with a high certainty, too. The constable would hear the noise himself, being sure of it.

I'd need to look in a lot more detail to be sure of this. But at least on a quick look, it appears that there's significant common law support for the idea that the government needs a significant likelihood of harm occurring before entering the home.

Anyway, I have no idea if the Supreme Court will be interested in this case. The Court has not been much interested in its Fourth Amendment docket recently. The state waived its opportunity to file a brief in opposition. But there are some significant common law materials on this question if the Court ends up interested in the issue.

The post New Cert Petition on Emergency Entry: What Was the Common Law Rule? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Montana Supreme Court Recognizes State Constitutional Right to a "Stable Climate System"

Last week, in Held v. Montana, the Montana Supreme Court held that the Montana Constitution's guarantee of a "clean and healthful environment" encompasses a right to a "stable climate system that sustains human lives and liberties." On this basis it concluded that legislative amendments to the State Energy Policy Act and Montana Environmental Policy Act barring the consideration of climate impacts and impacts beyond Montana's borders as part of statutorily mandated environmental reviews of some permit applications were unconstitutional. In the process, it also concluded that the citizen-suit plaintiffs had standing (in state court) to bring such claims. The vote was 6-1, with one justice dissenting on standing grounds.

Held v. Montana is the first decision by an appellate court in the United States recognizing a constitutional right to a "stable climate." This is no doubt significant. Efforts to vindicate such a claim in federal court, as in the Juliana litigation, have been unsuccessful beyond the trial court level. Yet the legal significance of this case is somewhat limited. The decision only affects activities in Montana and is based on provisions in the Montana state constitution expressly recognizing a right to a clean and healthful environment. And as a policy matter, the actual judgment--invalidating a limitation on MEPA reviews--will have no meaningful impact on climate change whatsoever. What activists are hoping for is that Held will spur other courts to follow suit, or that it will encourage further efforts to adopt meaningful climate mitigation policies.

This is not the first Montana court decision concluding that citizens could sue in state court to vindicate their state constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment. Part of what is interesting (and perhaps path-breaking) about the Held decision is that it appears to be the first in which the plaintiffs did not need to be able to identify any tangible way in which their constitutional rights were violated (such as by a tangible change in environmental quality), nor did they need to identify any way in which a favorable judgment would redress such injuries (such as by preventing or ameliorating identifiable environmental harm). So while the Court adopted a standing inquiry that paralleled that which is required in federal court, the substance of that inquiry was far more permissive.

As interpreted by the majority, the state constitutional right to a stable climate system is violated insofar as the state barred state agencies from considering climate-related imapcts as part of a legislatively mandated environmental review process. So while there was no claim that the MEPA environmental review process was itself constitutionally mandated, the state could not choose to exempt certain environmental questions--such as the effect of permitted activities on global climate change--from that review process. That allowing such review--indeed, that prohibiting all greenhouse gas emissions from all of Montana--would not do much to lessen the impacts of climate change in Montana (or anywhere else for that matter) did not matter. Limiting what is considered in the MEPA review process, by itself, constitutes an "injury" to the plaintiffs constitutional right "to a clean and healthful environment."

From Chief Justice McGrath's opinion for the Court:

It may be true that the MEPA Limitation is only a small contributor to climate change generally, and that declaring it unconstitutional will do little to reverse climate change. But our focus here, as with Plaintiffs' injuries and causation, is not on redressing climate change, but on redressing their constitutional injuries: whether the MEPA Limitation unconstitutionally infringes on Plaintiffs' right to a clean and healthful environment. . . .

the question is whether legal relief can effectively alleviate, remedy, or prevent Plaintiffs' constitutional injury, not on whether declaring a law unconstitutional will effectively stop or reverse climate change. … To make that a requirement for standing would effectively immunize the State from any litigation over whether its laws are in accordance with the "affirmative [constitutional] duty upon the[] government to take active steps to realize" Montanans' right to a clean and healthful environment.

According to McGrath, by limiting the review of climate impacts, the state legislature undermined the ability of the state and its citizens to address climate change.

MEPA mandates that the State take a "hard look at the environmental consequences of its actions" before it leaps, which is impossible when the State intentionally refuses to consider an entire area of significant environmental consequences. . . . Obviously, a clean and healthful environment cannot occur unless the State and its agencies can make adequately informed decisions. . . . . Nor can Plaintiffs be informed of anticipated impacts to the environment when the Legislature forecloses an entire area of review proven to be harmful to Montanans' right to a clean and healthful environment. . . . Nor will the Legislature be informed of whether laws are adequate to address climate change when MEPA precludes an environmental review addressing the impacts from potential state actions.

Justice Sandefur concurred separately, agreeing with the Court's bottom line, but disagreeing on some particulars. He wrote in part:

I first concur with the Majority on the easy question of whether Mont. Const. art. II, § 3 (right to "clean and healthful environment"), generically includes the right to a stable climate system that sustains human lives and liberties. However, the harder and more complex question unaddressed by the Majority, and the conspicuously absent particularized causation evidence in this case, is how that fundamental Montana constitutional right possibly can or should apply to restrictive MDEQ MEPA-compliance review of the gubernatorial energy policies originally at issue below, not to mention particular projects that otherwise comply with all applicable air quality review and permitting standards and requirements of the controlling federal Clean Air Act and subordinate Montana Air Quality Act regulatory scheme, in the face of the very real and uniquely complex global warming problem plaguing the entire planet, not just the slice of sky over Montana. . . .

The overly simplistic focus of Plaintiffs and the Majority of this Court on the undisputed and indisputable fact that global warming "is harming Montana's environmental life support system now and with increasing severity for the foreseeable future" is no more than a political and public policy statement of the obvious. As such, it further serves as a smokescreen diverting attention away from those inconvenient facts of record and the other similarly indisputable fact: accelerated global warming caused by fossil fuel burning and other human sources of greenhouse gases is a highly complex global problem, any solution or meaningful mitigation to or of which lies exclusively in the domain of federal and international public policy choices and cooperation, rather than in a flashy headline-grabbing rights-based legal case in Montana. . . .

Justice Rice dissented, arguing that the "growing urgency" of climate change "affords no discretion or authority to excuse the constitutional requirement that Plaintiffs bring a concrete case or controversy before the Court—a case or controversy that must be defined by constitutional principles governing justiciability and standing, not by policy significance or vogue." He continued:

These other measures may well move the executive and legislative branches to action, but they are not permitted to so compel the judicial branch. Failure to enforce constitutional case or controversy requirements inevitably turns a court into an ad hoc legislative body. Without a doubt, the debate about climate change, and related topics such as possible geoengineering solutions—from the enormous carbon dioxide vacuum facility in Hellisheidi, Iceland, to the massive direct carbon dioxide air-capture facility in Odessa, Texas, to stratospheric aerosol injection technology designed to deflect more and capture less sunlight and thus cool the earth, to enhancement of the capability of the oceans' phytoplankton habitat to draw and absorb carbon dioxide—are both fascinating and controversial, but courts must nonetheless resist the temptation to depart from their lane, and refrain from entering these matters except upon clear demonstration of a justiciable case or controversy as required by the constitution.

That does not exist here. The Court emphasizes the breadth of the Constitution's environmental protections, but that, of itself, does not create a case or controversy. Many constitutional provisions are considered to be "broad." All of the environmental cases relied upon by the Court involved a government action that operated upon, and thus directly impacted, the subject plaintiffs, who brought an action in each of those cases to challenge the particular government action affecting them. Here, as further analyzed below, there is no such operative government action—no project, no application, no decision, no permit, no enforcement of a statute—which directly impacted the Plaintiffs. Rather, the only government action raised here is an enactment of a statute that could operate to affect Plaintiffs if applied in an actual case. The District Court struck down these statutes as unconstitutional, even though the statutes had never operated upon the Plaintiffs, and then struggled to define what this result meant, because there was no actual pending dispute to which its ruling could attach. Consequently, instead of a "decree of conclusive character," . . . , the District Court entered a floating judgment of generic unconstitutionality.

As much as we want to encourage young people to involve themselves in the political process, that desire itself cannot turn Plaintiffs' compelling stories into constitutional standing. That is because Plaintiffs' stories are not legally unique. Like compelling stories could also be drawn from the more than one million other Montanans who are likewise affected by climate change—about how climate change has impacted them, affected their wellbeing, and created fear and concern about their future. Indeed, it is not only young people who have been impacted by climate change and are very concerned about it. "In the last generation, [climate] changes that have had a decisive influence on all social life have occurred"—was a description of the impact of climate change upon the generation that also endured the Great Depression and fought World War II. Is the World Getting Warmer?, supra, at 23. Climate change is universal in effect and nondiscriminatory; it affects everyone. And even if it has affected some persons more than others, that impact does not erase the population-wide effect of climate change.

Because there is nothing about Plaintiffs' stories that could not also be found within the collective experience of the entire Montana population, their allegations are not distinguishable from the general public at large, and thus erode a claim to standing. What is necessary for standing is a Montana government action that has directly impacted a member of the Montana population, which is absent here. As explained more specifically herein, the Court's ruling opens the courts for litigants, upon a hypothetical set of facts, to seek and obtain redress from courts by advisory opinions. I thus turn to the governing constitutional principles. . . .

While I agree the clean and healthful provision is an expansive right that is intended to apply to every citizen of Montana, it does not follow that any impact, current or imminent, upon a clean and healthful environment allegedly allowed by a statute alone constitutes a sufficiently concrete injury to every citizen for standing purposes, such that an action can be brought without demonstration of a personal stake in the litigation—that is, the government's application of the statute in a controversy affecting the citizen. . . .

standing requires that the MEPA Limitation be a cause of the injury, which is the degradation of a clean and healthful environment. An alleged injury cannot be a theoretical observation that the challenged MEPA framework is insufficient; rather, for standing purposes, a concrete current or impending violation of the constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment—the injury—by way of the government's application of the framework to the Plaintiffs—the cause—is required.

The post Montana Supreme Court Recognizes State Constitutional Right to a "Stable Climate System" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Pseudonymity OK for Transgender Prisoner's Challenge, But Rest of Filings Must Be Unsealed

From today's decision in Doe v. Ga. Dep't of Corrections, by Chief Judge William Pryor and Judges Adalberto Jordan and Stanley Marcus:

Plaintiff-Appellee, Jane Doe, is a transgender woman currently in the custody of the Georgia Department of Corrections ("GDOC") serving a sentence of life imprisonment. On December 6, 2023, she sued the GDOC and others (collectively, the "GDOC"), claiming that they were violating her Eighth Amendment constitutional rights by refusing to provide her medically necessary care to treat her gender dysphoria. The same day Doe filed suit in the district court, she filed accompanying motions, one seeking leave to proceed in the case anonymously and another seeking preliminary injunctive relief.

In resolving these motions, the district court issued a Pseudonym Order, granting Doe the right to proceed under a pseudonym, and a Preliminary Injunction Order, granting in part and denying in part her request for preliminary injunctive relief. The GDOC has filed an interlocutory appeal in this Court challenging both orders. The GDOC seeks to vacate both the district court's preliminary injunction and its pseudonym order. We will address that appeal in a separate opinion at a later date.

In the meantime, the GDOC has moved us to unseal the appellate record. While the parties hotly dispute whether we have jurisdiction now to review the district court's Pseudonym Order, there is no dispute that we have the power to decide a motion to unseal our own docket. "When presented with an appeal, [courts of appeals] routinely unseal documents that were sealed in the district court when those documents are used on appeal and there is no legal basis for sealing." The GDOC's cross-motion to unseal only addresses the appellate record accompanying this interlocutory appeal. We consider this to be a matter of considerable immediacy and find it appropriate to address it now, separate from our consideration of the merits of GDOC's interlocutory appeal.

As we've long recognized, "[l]awsuits are public events." We view "'[t]he operations of the courts and the judicial conduct of judges" as "matters of utmost public concern'" because "'[t]he common-law right of access to judicial proceedings, an essential component of our system of justice, is instrumental in securing the integrity of the process.'" This is especially the case in criminal trials where the public's right of access "plays a particularly significant role in the functioning of the judicial process and the government as a whole." Globe Newspaper Co. v. Super. Ct. (1982) (holding that a Massachusetts statute providing for the exclusion of the general public from criminal trials of specified sexual offenses involving a victim under the age of 18 violated the First Amendment).

Public scrutiny "enhances the quality and safeguards the integrity of the factfinding process," and "permits the public to participate in and serve as a check upon the judicial process." Moreover, "open proceedings may be imperative if the public is to learn about the crucial legal issues that help shape modern society." It is undeniable that "[i]nformed public opinion is critical to effective self-governance." For these reasons, the Supreme Court has held that "a right of access to criminal trials in particular is properly afforded protection by the First Amendment."

In civil cases, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure similarly provide that "[t]he title of the complaint must name all the parties." Fed. R. Civ. P. 10(a). Just as in the criminal context, this requirement is more than some procedural formality; it reflects the First Amendment's "guarantees [that] are implicated when a court decides to restrict public scrutiny of judicial proceedings." So, whenever we consider whether to close some aspect of a judicial proceeding, we cannot do so lightly. This is especially true when we are tasked with reviewing "civil trials" that "pertain to the release or incarceration of prisoners and the conditions of their confinement," which "are presumptively open to the press and public." "If it is beneficial to have public scrutiny of criminal proceedings that may result in conviction and punishment," then it is surely beneficial to allow public access to civil proceedings that affect that punishment..

Nevertheless, we've acknowledged that there may be compelling circumstances where it is appropriate to allow a party to proceed anonymously. After all, "[t]he public right to scrutinize governmental functioning … is not so completely impaired by a grant of anonymity to a party as it is by closure of the trial itself." This is because at least sometimes party anonymity may not "obstruct the public's view of the issues joined or the court's performance in resolving them." Thus, the public's interest in a party's name, the who, sometimes may be far less significant than disclosing the how and the why surrounding the decisional process. We've said, for example, that "[a] party may proceed anonymously in federal court by establishing a substantial privacy right which outweighs the customary and constitutionally-embedded presumption of openness in judicial proceedings." A party seeking anonymity, however, bears the heavy burden of establishing that her privacy rights outweigh the powerful presumption of open judicial proceedings.

We have found, on occasion, a substantial privacy interest in cases involving mental illness, homosexuality, and transsexuality…. The case before us—which arises out of Doe's transgender status and her gender dysphoria treatment—deals with information of the utmost intimacy. The facts, which are now part of this appellate record, describe Doe's struggles with gender dysphoria, her LGBTQ+ status, her mental illness, her attempts at self-mutilation including self-castration, and multiple suicide attempts. In fact, the GDOC does not contest that this case deals with highly sensitive and personal information. Instead, it argues that Doe has forfeited any privacy right in this information by filing previous lawsuits that publicly revealed much of the same information at stake here.

We have studied this interlocutory record closely and are convinced that there remain sufficiently compelling reasons to allow Doe to proceed anonymously in this proceeding, and at this time. As everyone seems to agree, revealing Doe's identity in this interlocutory proceeding would compel the disclosure of deeply personal and private information associated with a high degree of social stigma. Moreover, the danger of physical harm appears to be real. We are particularly reluctant to unseal Doe's identity now because this cross-motion comes to us on appeal from a preliminary injunction order, on a preliminary record, and the district court is still hearing the bulk of the underlying case. The totality of the circumstances counsels that Doe should be allowed to proceed under a pseudonym in these interlocutory proceedings.

That being said, the public's right of access to judicial proceedings "includes the right to inspect and copy public records and documents." We recognize that this is a case pertaining to conditions of prisoner confinement and it is undeniable that the public has a powerful interest in the nonidentifying information involved in these proceedings.

Most pertinently, the public has a strong interest in access to the transcript of the preliminary injunction hearing which, like much of the interlocutory record, has been filed in our docket under seal. Indeed, if the right to inspect judicial records is to mean anything, it must mean that the public has a right to review the evidence that led the district court to its preliminary conclusions, and that will undoubtedly inform this Court in addressing the matters now before us. Unsealing the materials on file in our Court but redacting the Plaintiff's name is consistent with the district court's Pseudonym Order and will not disturb the ability of the district court to conduct the ongoing proceedings as it sees fit.

Accordingly, while we conclude that it remains wise now to keep Doe's identity sealed, we can discern no sound reason to keep the full interlocutory record on file in our Court under seal. We, therefore, direct the parties to counsel with each other, review the materials that have been filed under seal in our Court, and file with us in an unsealed form the appellate record, after redacting from those materials Doe's name and such other information in the record that would reasonably identify her.

In short, the GDOC's motion to unseal the appellate record is GRANTED IN PART AND DENIED IN PART. The parties shall file an appropriately redacted version of the currently sealed record evidence within thirty (30) days of the date of this Order.

This is consistent with other decisions that have generally allowed pseudonymity for litigants who are disclosing their transgender status.

The post Pseudonymity OK for Transgender Prisoner's Challenge, But Rest of Filings Must Be Unsealed appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Court Blocks Arkansas Law That Limits "Harmful to Minors" Books in Public Libraries and Bookstores, and Also

An Arkansas statute (Act 372) makes it a crime (in its section 1) for librarians and booksellers to "[f]urnish a harmful item to a minor." The U.S. Supreme Court has held that the First Amendment doesn't protect distribution of "obscenity," a narrow category that basically covers hard-core pornography. To be obscenity, a work must satisfy all three of the following elements, largely drawn from Miller v. California (1973), though with extra detail added by Smith v. U.S. (1977), Pope v. Illinois (1987), and Brockett v. Spokane Arcades, Inc. (1985):

"the [a] average person, [b] applying contemporary community standards, would find that the work, [c] taken as a whole, [d] appeals to the prurient interest" (which means a "shameful or morbid" interest in sex as opposed to a "normal, healthy" interest); "the work depicts or describes, [a] in a patently offensive way [under [b] contemporary community standards], [c] sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law"; and "the work, [a] taken as a whole, [b] lacks serious [c] literary, artistic, political, or scientific value[, [d] applying national standards and not just community standards]."And the Court has also held that the law may bar distribution to minors of sexually themed material, if it fits within what's basically the Miller test with "of minors" or "for minors" added to each prong (e.g., "the work taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value for minors"). Ginsberg v. New York (1968), a pre-Miller case, upheld a law that implemented the then-current obscenity test with "to minors" added at the end of each prong; most lower courts and commentators have assumed that Ginsberg plus Miller justify laws that implement the Miller-based test with "to minors" added to each prong as well. This category is often labeled material that is "obscene for minors" or "harmful to minors." (It's a completely different First Amendment exception from the one for child pornography, which focuses not on the recipient of the material but on the person depicted in the material.)

Now of course minors vary sharply in age, so this raises the question: Is a work "obscene as to minors" when it has value for a 17-year-old (or isn't patently offensive when displayed to a 17-year-old) but lacks value for a 5-year-old? Back in 2004, the Arkansas Supreme Court basically said such a work is indeed obscene as to minors; and because of this, Judge Timothy Brooks (W.D. Ark.) held today in Fayetteville Public Library v. Crawford County, Section 1 of Act 372 is likely unconstitutional:

Arkansas's highest court [has concluded] that a broad interpretation [of "harmful to minors"]—which swept in books that would be considered harmful to the youngest of minors—was what the Arkansas General Assembly intended when drafting the law. The Court explained:

If the younger minors are to be protected from "harmful" materials, surely the General Assembly did not intend for those younger children to be permitted to access materials that would arguably be "harmful" to them, even though not "harmful" to an older child. We cannot construe Arkansas' statutory law in such a way as to render it meaningless, and we will not interpret a statute to yield absurd results that are contrary to legislative intent.

Shipley, Inc. v. Long (Ark. 2004)…. Since this term ["harmful to minors"] has been construed broadly by the Arkansas Supreme Court to mean material that is obscene to the youngest of minors, it was up to the General Assembly to write a narrowly tailored law with this definition in mind. That did not happen, and the law's overbreadth should not come as a surprise to its drafters….

Given the above, the only way librarians and booksellers will be able to comply with Section 1 and still allow those under the age of eighteen to enter their facilities is to keep them away from all books with sexual content. This could be done by creating strict adults-only areas—into which would go potentially hundreds of books, from disposable paperback romance novels to classics of literature like Romeo and Juliet, Ulysses, Catcher in the Rye, The Handmaid's Tale, or The Kite Runner.

In other words, to avoid criminal penalties under Section 1, librarians and booksellers must impose restrictions on older minors' and adults' access to vast amounts of reading material. Creating segregated "18 or older" spaces in libraries and bookstores will powerfully stigmatize the materials placed therein, thus chilling adult access to this speech. See, e.g., Doc. 99-7, ¶ 5 (Farrell Decl.) (testifying that browsing in an adults-only room "would signal to others that" she is "interested in reading pornography"); Doc. 99-19, p. 18 (Caplinger Depo.) (describing stigma that would attach to adults-only area of the library and implication that the books would "not just [be] inappropriate, but somehow pornographic or obscene").

If the General Assembly's purpose in passing Section 1 was to protect younger minors from accessing inappropriate sexual content in libraries and bookstores, the law will only achieve that end at the expense of everyone else's First Amendment rights. The law deputizes librarians and booksellers as the agents of censorship; when motivated by the fear of jail time, it is likely they will shelve only books fit for young children and segregate or discard the rest. For these reasons, Section 1 is unconstitutionally overbroad….

{Notably, there is no exemption for parents or guardians under Section 1. The Court surmises that if a parent were to act as a straw buyer or borrower of a book that a prosecutor deemed "harmful" to a young minor, criminal liability could attach if the parent then made the material available to her seventeen-year-old child.}

The court also held that Section 1's prohibition on people "present[ing]," "mak[ing] available," and "show[ing]" such material to minors is also unconstitutionally vague because it leaves "leaves librarians and booksellers unsure about whether shelving books they know contain sexual content may subject them to criminal liability." To quote the court's opinion at the preliminary injunction stage,

During the evidentiary hearing, the Court asked the State whether "makes available" meant "merely having [a book] on a bookshelf with nothing harmful on the cover or the spine, merely having it on a shelf with other books," and the response was, "I'm not sure we go that far." The State's attorney suggested, however, that it was possible that liability could attach to booksellers or librarians "if there was an open book that was just on the shelf" and the bookseller or librarian "kn[ew] for a fact the minor was actually viewing the material and then willfully turn[ing] a blind eye to it." This explanation demonstrates the challenge facing booksellers and librarians. There is no clarity on what affirmative steps a bookseller or librarian must take to avoid a violation.

The court also held that another provision of the Act, Section 5—which provided that books could be challenged as "inappropriate" for minors, and that such "inappropriate" books would need to be "withdraw[n] or "relocate[d]"—was likely unconstitutional as well, partly because it's too vague:

Section 5's pivotal term, "appropriateness," is susceptible to multiple interpretations and all but guarantees that the challenge process will result in the withdrawal or relocation of books based on their content or viewpoint. As stated, any book, even one written for an adult reader, could be deemed "inappropriate" and subject to challenge under Section 5.

Though the State asks that Plaintiffs have faith that Arkansas's local elected officials will preserve, protect, and defend their First Amendment rights, the Court's view of the matter is not quite so sanguine—particularly given the cautionary tale that the Virden case presents. There, quorum court members directed the librarian to move children's books out of the children's section into a separate area they euphemistically named "the social section." Judge Holmes found it "indisputable that the creation and maintenance of the social section was motivated in substantial part by a desire to impede users' access to books containing viewpoints that are unpopular or controversial in Crawford County."

Tellingly, when a Crawford County Library Board member was asked under oath why the books were moved to the social section, his answer was that the books were "inappropriate." And County Judge Keith, who under Section 5 would be required to "present" to the quorum court all books "being challenged," testified in his deposition that he did not know what "appropriate" meant in the context of Section 5 but guessed it could mean "different thing[s] for different people."

In the absence of a statutory definition of "appropriateness," the Court turns to the dictionary, which defines it as "the state of being suitable for a particular person, condition, occasion or place." Given this definition, it is difficult, if not impossible, to assess a challenged book's "appropriateness" without considering its content, message, and/or viewpoint. In fact, Section 5 specifically contemplates that a library review committee or local governmental body consider the material's "viewpoint." The law cautions only that a book should not be withdrawn from the library's shelves "solely for the viewpoints expressed within the material." Section 5 is constitutionally infirm because it "fail[s] to define the [key] term at all, and, consequently, fails to provide meaningful guidance for those who enforce it."

Other important terms in Section 5 are similarly vague. The statute uses both "withdraw" and "relocate" with respect to challenged books. Obviously, withdrawing a book from the library's collection would pose a greater burden on access to protected speech than relocating the book to another section of the library, but Section 5 presents both options as though they were equivalent. Moreover, if a library committee or local governmental body elected to relocate a book instead of withdrawing it, Section 5 contemplates moving the book "to an area that is not accessible to minors under the age of eighteen (18) years"—without defining what "accessible to minors" means. If Section 5 were to take effect, libraries would have to guess what level of security would be necessary to satisfy the law's "[in]accessib[ility]" requirements. For all of these reasons, the Court finds that Section 5 fails the "stringent vagueness test" that applies to a law that interferes with access to free speech.

And the court concluded that section 5 was also likely unconstitutional because it was impermissibly content-based:

The challenge procedure in Section 5 merits strict scrutiny. At each step in the appeal process, evaluators must consider the content of the library material to screen for "appropriateness" before deciding whether the public should be deprived access to the material. Therefore, any successful challenge would result in a content-based restriction on otherwise constitutional speech—unless the challenged book met the legal definition of obscenity, which city governments are not required to consider….

If Section 5 is intended to protect minors, it is not narrowly tailored to that purpose. Nor is Section 5 limited to reading material that is obscene or "harmful to minors," which will significantly burden constitutionally protected speech….

The State's defense of Section 5 boils down to an argument that censorship of otherwise constitutionally protected speech is acceptable because every selection decision that affects a public library's collection—from the original purchase of materials by librarians, to the books' sequestration on special shelves or behind locked doors, to their outright removal from the collection—is "government speech" not subject to constitutional scrutiny. But Section 5 has nothing to do with the library's curation decisions, so if indeed such decisions constitute government speech, the State's arguments in that regard are unavailing. First of all, no one is arguing that librarians are violating their patrons' First Amendment rights through curation decisions. Secondly, burdening access to books within a public library collection or removing books from that collection due to content or viewpoint—which Section 5 permits, if not encourages here—implicates the First Amendment and does not qualify as protected government speech. {Just six months ago, the Eighth Circuit held that in the context of public school libraries—which are subject to more government restriction than public community libraries—"it is doubtful that the public would view the placement and removal of books … as the government speaking." GLBT Youth in Iowa Schs. v. Reynolds (8th Cir. 2024).}

"The right of freedom of speech … includes not only the right to utter or to print, but the right to distribute, the right to receive, the right to read and freedom of thought …." "[T]he State may not, consistently with the spirit of the First Amendment, contract the spectrum of available knowledge." And when it comes to children, it is well established that "minors are entitled to a significant measure of First Amendment protection" that the government may restrict "only in relatively narrow and well-defined circumstances," which are not present here. It is also well established that "[s]peech that is neither obscene as to youths nor subject to some other legitimate proscription cannot be suppressed solely to protect the young from ideas or images that a legislative body thinks unsuitable for them." Finally, when it comes to public spaces, like public libraries, "the governmental interest in protecting children from harmful materials … does not justify an unnecessarily broad suppression of speech addressed to adults."

The post Court Blocks Arkansas Law That Limits "Harmful to Minors" Books in Public Libraries and Bookstores, and Also appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Not Only Is [the Race Discrimination Plaintiff] a Perpetual Claimant, He Is a Holdup Artist"

From Saturday's decision in Rogers v. Low Income Investment Fund, decided by Judge William Alsup (N.D. Cal.):

In this employment-discrimination action, a non-profit community development organization and its then-employees move for summary judgment against a job applicant's claims that they did not hire him for a job monitoring grants in low-income communities because he is black. The head of human resources who communicated the denial and bore the brunt of his accusations now also moves for summary judgment. Both motions are GRANTED. A motion for sanctions is GRANTED….

The whole opinion is long (over 8700 words), so I just thought I'd excerpt the sanctions section, which also discusses some of the facts and some of the bases the court gave for granting summary judgment; for more, see the full opinion:

As a result, the merits of this action have been decided against Rogers, as have the merits of every one of Rogers's previous discrimination actions brought and concluded in this district. Now, LIIF moves for sanctions.

Rogers is a perpetual claimant. Over ten years ago, a state court [in San Diego County] found Rogers vexatious. Recently, after Rogers had not requested to file a new action in that county for more than five years, Rogers's repeated application for the order to be vacated was finally granted. {The form order does not provide a reasoned decision, but the five-year threshold for filings in the county may have been decisive ….} Rogers by then had relocated to the Bay Area, and the record shows his litigation energies are now directed here.

Rogers has abused the right to come to court by pursuing an unmeritorious cause and by trying to extort a settlement by threat of defamation. The sanctions motion explains that such conduct could amount to criminal extortion, and plainly amounts to bad faith. The motion also identifies attorney's fees that but for Rogers's improper conduct LIIF and its employees would not have incurred.

As examples of the conduct:

When LIIF wrote asking for a time Rogers could sit for his deposition, Rogers did not respond. Instead, the next day, he emailed one of LIIF's donors to assert that on "numerous occasions" LIIF "has refused to hire African Americans" and that it should defund LIIF. His sworn deposition revealed that he did not then have even one example of another black applicant having been rejected. Defense counsel prepared a cease-and-desist letter[.] With three days to go before his Court-ordered deposition, Rogers publicly filed LIIF's insurance policy and his demand they settle his claims for an amount under its limits. Eight minutes later, he emailed LIIF's counsel to state that "I won't rule out [contacting donors again] in the future depending on how you respond." Defense counsel responded. With two days to go before close of discovery, Rogers emailed defense counsel, asserting among other things that "a failure to respond will cause me to contact your donors and supporters which could financially jeopardize your organization," that "[i]n furtherance, I just may notify certain press release agencies such as BUSINESS WIRE," and that "Things will escalate. I promise."Notably, Rogers's emails and letters broadly alleged gross discrimination while attaching no documentation for those claims. He later admitted that he lacked evidence, as one example, showing that LIIF "has refused to hire African Americans in its Finance and Operations Department on numerous occasions." By contrast, Rogers's emails and letters specifically asserted what he did know: The "settlement offer is around 13.4% of the Employment Practices (Part 2) liability value on [your] insurance policy." And, he attached documented evidence to one such letter: The insurance policy, which his diligence had dug up.

To compensate for the time spent responding to these improper settlement offers as well as preparing the sanctions motion here, the motion tallies and seeks $5,830.00 in fees accrued by LIIF's attorneys.

In Rogers's two-page opposition, which he filed more than a week late, Rogers states: "Defendant has decided to waste the Court's time with this senseless, incompetent, and ridiculous motion." Rogers does not bother to rebut that he contacted donors in bad faith. Instead, he invokes a totally new fundamental right: free speech. He fails to appreciate the limits to that right. E.g., United States v. Hutson (9th Cir. 1988) (re extortionate speech) (adopting United States v. Quinn (5th Cir. 1975)). More to the point, he fails to remain focused on the conduct for which the motion seeks compensation.

The right to be free from discrimination is fundamental, and the right to petition preserves that right and is likewise fundamental. And yet, for the same reasons, defending against aggressive accusations about such grave concerns is costly—for private defendants and the public's courts. Those costs bring no benefit when claims are brought and litigated in bad faith or through conduct tantamount to bad faith. Such costs are compensable.

A court may exercise its inherent power to impose sanctions for bad-faith conduct. Across this case, Rogers combined reckless disregard for the truth and worse, with frivolousness (claims he prosecuted for months by "mistake"), harassment (badgering, baiting, and belittling remarks in his pre-litigation emails, pleadings, and even summary judgment papers on points unrelated to the merits), and improper purpose (diligence in getting a payout, not in much else). The most egregious examples of his conduct were the threats to make false or reckless statements to third parties to imperil LIIF's finances if LIIF did not settle. Just as Rogers was entitled to bring his claims in court, defendants were entitled to reject settlement and bring their defenses there, too. Instead, turning the norms inside out, Rogers filed his settlement demands on the public record. Not only is Brian Rogers a perpetual claimant, he is a holdup artist.

Indeed, an audacious holdup artist: Our hearing on this motion addressed extortion directly, an existing hearing respecting the upcoming trial announced that an order on the still-pending motions would issue within five days, and still Rogers did as follows:

With four days to go before an order on the motions was said to issue, Rogers emailed LIIF's CEO and employees, but not LIIF's litigation counsel, stating "LIIF has nobody worthy to represent you in court in two weeks. Now is the time to try to develop a settlement in this case as you know the trial may begin as early as January 6, 2025 which is two weeks from now [sic]. Your failure to respond to my prior settlement letters will now result in me contacting YOUR donors and grant providers again about your conduct which could impair your organization as a going concern." LIIF's litigation counsel docketed Rogers's email, and responded to Rogers with a renewed cease-and-desist letter; and, With three days to go before an order on the motions was said to issue, Rogers responded to defense counsel: "You are wasting your time and the Court's time with these frivolous motions. In fact, they are quite laughable. The judge does not have the time to respond to your silly diatribe and ridiculous arguments. My speech and communication is protected under the FIRST AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION. The Court can't do anything about my FIRST AMENDMENT rights. Let's wake-up ! Have you been to law school ? It appears that you have forgotten much and learned little of anything.This order finds that Rogers pressed his extortionate settlement demands in bad faith, rather than litigate his claims with diligence in court, and that but for this unreasonable conduct LIIF would not have needed reasonably to respond to those demands or to prepare the sanctions motion here, which resulted in $5,830 in extra attorney's fees. Rogers now lacks the resources to compensate the movant, as he proceeds in forma pauperis. Therefore, THE FOLLOWING SANCTIONS ARE ORDERED:

A LIEN ON SETTLEMENTS OR JUDGMENTS is imposed in the amount of $5,830.00 payable to the movant, Low Income Investment Fund, against any monies Rogers receives from any settlement(s) or judgment(s) of any claim(s) brought by Rogers in any court anywhere; Low Income Investment Fund MAY FILE a "Notice of Lien on Settlements or Judgments" in any pending or future action brought by Rogers in any court, wherein it shall assert the lien imposed by Paragraph 1 and attach this order; and, The Court shall retain jurisdiction to the extent necessary to enforce these sanctions.This means that the first $5,830.00 of any future settlements or judgments in favor of plaintiff will go to the movant (until $5,830.00 is paid)….

Note that the line between permissible litigation activity and sanctionable or even criminal extortion can often be hard to draw. (That's a special case of the Blackmail Paradox.) If you have at least a plausible claim, and you offer to settle it before filing a Complaint, that's good lawyering. Indeed, it's permissible even if it's clear to everyone that, once the Complaint is filed, the media will pick up the Complaint and publicize the allegations against the defendant. And it's permissible even if your firm has in the past itself put out press releases about the claims, so the defendant knows you're likely to do it again.

But if the claim is clearly baseless, or the amount you demand is clearly in excess of what's allowed (see also here), then that may be criminal extortion. Expressly threatening publicizing your allegations may also get you in trouble, especially if you're threatening accusing someone of crime.

Cases such as this seem to be near the borderline. Here, for instance, is an excerpt from Chandler v. Berlin (D.D.C. 2020):

That leaves Plaintiff's counsel's threats to "take all appropriate steps and leverage our contacts in the media … to put your prior clients on notice regarding ICI's fraudulent business model, and to prevent you from defrauding others with fake reports in the future." This, too, is not sanctionable. "Mere warnings by a party of its intention to assert nonfrivolous claims, with predictions of those claims' likely public reception, are not improper." Sussman v. Bank of Israel (2d Cir. 1995). As discussed, Plaintiff asserted at least one colorable claim of defamation, which was largely premised on the factual assertions regarding Defendants' business practices outlined in the Demand Letter. Thus, it was not improper for Plaintiff to threaten to publicize these allegations and predict their "likely … reception" with Defendants' clients, particularly given that Plaintiff never directly contacted Defendants' clients or otherwise interfered with Defendants' businesses. See also Revson v. Cinque & Cinque, P.C. (2d Cir. 2000) (reversing the district court's finding that counsel's "threat[] to interfere with the Firm's other clients provide[d] a basis for sanctions" in part because counsel never directly contacted the clients (cleaned up)); cf. Bouveng v. NYG Capital LLC (S.D.N.Y. 2016) (holding that a plaintiff's counsel's "references to potentially embarrassing litigation" in a prelitigation demand letter and email were not extortionary where they were "part of a larger endeavor to obtain recompense for a perceived wrong").

Here, to be sure, there were threats to "directly contact[]" defendant's donors, though query how much of a difference that should make. In any event, this struck me as an interesting case to pass along.

Theodora Lee and Pamela Woodside (Littler Mendelson, P.C.) represent defendants.

The post "Not Only Is [the Race Discrimination Plaintiff] a Perpetual Claimant, He Is a Holdup Artist" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] Did President Biden's Justice Department Confer with the Victims' Families Before the President Commuted Federal Death Sentences?

This morning, the White House announced that President Biden has commuted the death sentences of 37 of the 40 federal death row inmates. I wonder whether the President has ignored the rights and interests of crime victims' family members in granting mass commutations.

The Justice Department does have in place an announced policy for processing requests for executive clemency in capital cases. Under the Department's "Rules Governing Petitions For Executive Clemency sec. 1.10/Procedures Applicable to Prisoners Under a Sentence of Death Imposed by a U.S. District Court," victims' families (like a death row inmate's representatives) are supposed to generally have an opportunity to make a presentation to the Office of the Pardon Attorney before clemency is granted:

(c) The petitioner's clemency counsel may request to make an oral presentation of reasonable duration to the Office of the Pardon Attorney in support of the clemency petition. The presentation should be requested at the time the clemency petition is filed. The family or families of any victim of an offense for which the petitioner was sentenced to death may, with the assistance of the prosecuting office, request to make an oral presentation of reasonable duration to the Office of the Pardon Attorney.

In reading today's "fact sheet" from the White House, I see no reference to the Department having contacted victims' families or otherwise conferring with them before making the decision. The large numbers of commutations the President issued at the same time--all in the waning days of the current Administration--makes me wonder whether the Administration has simply left victims' families outside of the process.

As the Justice Department rules suggest, a fair process in considering commutations would necessarily involve at least hearing from victims' families before making any final commutation decision. And there does not appear to be any logistical barrier to conferring with the victims' families. The U.S. Attorney's Offices who have handed these 37 cases are, no doubt, have ways to quickly contact family members. The federal Crime Victims' Rights Act (CVRA) broadly commands that victims (and family members in homicide cases) have the "right to be treated with fairness and with respect for the victim's dignity and privacy." Failing to confer with victims family members who have gone through a long and arduous capital trial and sentencing process is difficult to square with this command. And the Justice Department's own Attorney General Guidelines for Victims and Witness Assistance indicate that "[t]his broad-based right [to fair treatment] is central to the purpose of the CVRA and should serve as a guiding principle for Department personnel that governs all interactions with crime victims." A.G. Victims Guidelines at 70, art. III, sec. j.

My suspicions that the victims' families have been ignored in this commutation process are heightened by the fact that in another case--U.S. v. Boeing--the Department has paid little attention to victims' families. Indeed, a federal judge has found that the Department violated the federal Crime Victims' Rights Act in reaching its decisions without conferring with victims' family members.

Here, of course, the President has constitutional power to commute federal sentences, including federal death sentences. And in this short post, I don't take a position on the substantive pros and cons of the 37 commutations. My question is simply a procedural one that goes to the fairness of the process: In making the commutation decisions, has the President followed standard procedures and given the victims' families an opportunity to confer with appropriate officials before making a final decision? Perhaps such conferrals have taken place and these details have not been publicly disclosed. But from the information I've been able to review quickly, that seems unlikely … and, once again, victims' families rights and interests are apparently being ignored in some larger political manuever.

The post Did President Biden's Justice Department Confer with the Victims' Families Before the President Commuted Federal Death Sentences? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Advanced Stalking"

From Guam Code Ann. § 19.70:

(a) A person is guilty of simple stalking if he or she willfully,

maliciously, and repeatedly, follows or harasses another person or who

makes a credible threat with intent to place that person or a member of his or

her immediate family in fear of death or bodily injury.(b) A person is guilty of advanced stalking if he or she violates

Subsection (a) of this Section when there is a temporary restraining order or

an injunction or both or any other court order in effect prohibiting the

behavior described in that Subsection against the same party.

Rather an odd locution, it seems to me; the term would normally be something like "aggravated stalking," or the crime might be divided into first-degree and second-degree stalking. But legislatures can name things as they please.

The post "Advanced Stalking" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: December 23, 1745

12/23/1745: Chief Justice John Jay's birthday.

Chief Justice John Jay

Chief Justice John JayThe post Today in Supreme Court History: December 23, 1745 appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers