Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 178

January 27, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Monday Open Thread

The post Monday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Post] One-Man Rule

So President Trump has fired a whole host of federal agency Inspectors General without providing either the 30-day notification to Congress or the "substantive rationale, including detailed and case-specific reasons" why an Inspector General was removed, both of which are, unambiguously, required by law. Josh Blackman asks:

"What is Trump's justification for not providing the notification? Maybe the restriction can't be applied to a new President who has just come into office? Does Trump think that the thirty-day clock infringe on his Article II removal power? Is he daring one of the IGs to sue him, to set up a Supreme Court test case?"

Let me respectfully suggest that Josh has overlooked the most obvious answer to the question, which is: He [Trump] couldn't care less. He has figured it out: He can do whatever he wants, and nobody can stop him. Unilaterally impose 25% tariffs on Colombian imports? Do it. Withhold federal disaster relief to cities that don't assist ICE agents carrying out their raids? Absolutely. Halt all payments due for dispersal under NIH research grants until grantees dismantle their DEI programs? Sure.

Does anyone actually believe that, during the discussion in the Oval Office concerning those moves, Trump asked: "Are we sure we have statutory and constitutional authority to do this?"?

He knows, and we know, exactly how this plays out.

1. There's a fair bit of outrage, from reasonable people, about the illegality of the action.

2. Some of the fired IGs sue in federal court to void their dismissals on the ground that they were unlawful.

3. Considerable tangential discussion about "standing" and "mootness" ensues, but in the end - we're talking maybe May or June at the earliest - they win!

4. Judgment is stayed while Trump appeals.

5. The appeals court takes a look at all the complicated removal clause/Article II arguments and issues its judgment . . . .

Meanwhile. By this time, of course, pretty much everyone has forgotten what the case was about.

But much more importantly: when Trump finally loses the case and the court issues its order - "Your actions were unlawful. You must reinstate the IGs effective immediately" -- what happens then?

6. We all know what happens next. What happens then is that he says "Go f*** yourself."

The End.

I guess there are just a lot of people who think one-man rule is just what we need at the moment. I hope they're right, because it is what we've got.

The post One-Man Rule appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] First Liberty Institute Is Hiring

I am happy to pass along this announcement from my friends at First Liberty Institute, one of the premier religious liberty organizations around:

First Liberty Institute is seeking intelligent, passionate, driven team members to help us advance First Amendment rights across the nation. Our organization is the largest law firm in the nation dedicated exclusively to defending religious freedom for all Americans. Our firm has won multiple landmark cases at the U.S. Supreme Court and is positioned for unprecedented impact in 2025.

Open positions include:

Associate Counsel, Counsel, and Senior Counsel Locations: Various, with a concentration in our Washington, D.C. and Plano, TX offices. Commitment: Full-time positions. Requirements: J.D. required. Judicial Fellowship Location: Plano, TX office. Commitment: Full-time position; one-year fellowship. Requirements: Must have completed at least one federal clerkship; J.D. required. Learn more here. Judicial Research Director Location: Washington, D.C. office. Commitment: Full-time position. Requirements: J.D. required. Judicial Researcher Locations: Various, with a concentration in our Washington, D.C. and Plano, TX offices. Commitment: Full- or part-time positions available. Requirements: J.D. preferred. Public Interest Legal Fellowship Location: Plano, TX office. Commitment: Summer 2025. Requirements: Rising 2L or 3L law student. Application process: Available here.You are welcome to forward this information to your contacts. If you are interested in learning more about these opportunities, please contact Lori Ross at lross@firstliberty.org and cc Kassie Dulin at kdulin@firstliberty.org. Job descriptions are available upon request.

The post First Liberty Institute Is Hiring appeared first on Reason.com.

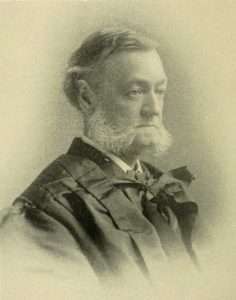

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: January 27, 1955

1/27/1955: Chief Justice John Roberts's birthday.

Chief Justice John Roberts

Chief Justice John Roberts

The post Today in Supreme Court History: January 27, 1955 appeared first on Reason.com.

January 26, 2025

[Jonathan H. Adler] What Process Is Due Before Property Is Destroyed?

The McIntoshes own a mobile home park in Madisonville, Kentucky. After a tenant complained, the city found mold and mildew in one of the homes, condemned it, and ordered it demolished. The McIntoshes challenged the city's action (albeit after the home was destroyed) on several legal grounds, but the trial court was unmoved. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, however, found the trial court was too quick to dismiss the procedural due process claim.

Chief Judge Sutton summarized the case.

The City of Madisonville condemned one of several mobile homes that Michael and Rebecca McIntosh own in their Kentucky town. The City demolished the property a month later. The McIntoshes filed this § 1983 action in response, alleging that the City deprived them of their due process rights to notice and the opportunity to be heard before tearing down the mobile home, among other claims. The district court granted the City's motion for summary judgment. Because triable issues remain over whether the City provided the McIntoshes an adequate opportunity to be heard, we reverse its disposition of this claim and affirm its handling of the other claims.

On the McIntoshes' procedural due process claim, the city may have provided them with adequate notice, but they do not appear to have given them an adequate opportunity to be heard to contest the condemnation and prevent the property's destruction. In particular, the city had no process n place to provide the hearing called for by the city's own municipal code. (Apparently city officials preferred to "sit down and have a conversation with" affected property owners.)

Judge Murphy offered an additional concurrence that is worth a read. It explores how the expansion of Due Process protections to a broader category of claims created countervailing pressure to lessen the degree of protection provided. I've posted the text after the break.

This case shows that an evolving-standards approach to constitutional interpretation can destroy rights just as much as it can create them. The Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause makes it illegal for a State to "deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law[.]" U.S. Const. amend. XIV, § 1. This constitutional text raises two basic questions: Has a State threatened to deprive a person of "life, liberty, or property"? If so, what is the "process" that is "due" for this threatened deprivation?

Historically, the Due Process Clause provided capacious protections ("due process of law") to a modest set of interests ("life, liberty, or property"). To start, the words "life, liberty, or property" traditionally reached only a "a small collection of rights." Frank H. Easterbrook, Substance and Due Process, 1982 Sup. Ct. Rev. 85, 97–98. They referred to what William Blackstone called "the 'absolute' rights" of individuals in the state of nature and what we would call "private rights" today. Caleb Nelson, Adjudication in the Political Branches, 107 Colum. L. Rev. 559, 566–67 (2007); see 2 St. George Tucker, Blackstone's Commentaries 123–24, 128–29 (1803). According to Blackstone, a person's specific right to "property" "consist[ed] in the free use, enjoyment, and disposal of all his acquisitions, without any control or diminution, save only by the laws of the land." 2 Tucker, supra, at 138. So the word "property" referred to both the "bundle of rights" that a person obtained when becoming the owner of lands or goods as well as those lands and goods themselves. Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, 594 U.S. 139, 150(2021); 2 Samuel Johnson, Dictionary of the English Language 418 (4th ed. 1773); see Restatement (First) of Property ch. 1, intro. note (Am. L. Inst. 1936).

Next, the phrase "due process of law" provided robust protections to these narrow interests. As the Supreme Court explained before the Fourteenth Amendment's adoption, the phrase referred to the "settled usages and modes of proceeding existing in the common and statute law of England" that the colonists adopted on this side of the Atlantic. Murray's Lessee v. Hoboken Land & Improvement Co., 59 U.S. 272, 277 (1856). Or, as Justice Story put it, the phrase referred to the "process and proceedings of the common law." 3 Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States § 1783, at 661 (1833). Of most relevance here, this incorporation of common-law protections set a "constitutional baseline" of "judicial process," presumptively requiring a neutral court to stand in between the government and its people's private rights. SEC v. Jarkesy, 144 S. Ct. 2117, 2145 (2024) (Gorsuch, J., concurring); see Nathan S. Chapman & Michael W. McConnell, Due Process as Separation of Powers, 121 Yale L.J. 1672, 1807 (2012); Nelson, supra, at 569–70. The people thus had the right "to 'judicial' determination of the facts that bore on" the government's claim that it could deprive them of private rights. Nelson, supra, at 591.

At first blush, this historical approach to the Due Process Clause makes this case look easy. Frank Wallace, the building inspector for the City of Madisonville, Kentucky, condemned a mobile home owned by Michael and Rebecca McIntosh after finding that this home violated various municipal building codes. Thirty days later, Wallace and other officials tore the home down over Mr. McIntosh's continued objections. Before destroying this home, the city officials never initiated a court proceeding to decide whether the home's dilapidated state did, in fact, render it subject to condemnation under the ordinance. And, as Chief Judge Sutton's opinion explains, the officials also identify no viable state-law path by which the McIntoshes could have obtained a judicial finding about the home's condition. The officials instead argue that they provided the McIntoshes with the required process simply by giving them the option to negotiate with Wallace over the home's problems and to "appeal" his finding to the city attorney. See McIntosh v. City of Madisonville, 2024 WL 1288233, at *6 (W.D. Ky. Mar. 26, 2024).

I find little support in the Due Process Clause's original meaning for this (somewhat astonishing) claim. There can be no doubt that the McIntoshes' ownership interest in their mobile home fell with the traditional definition of "property." And there can be no doubt that the city officials "deprived" the McIntoshes of this property when they destroyed it. The officials' conduct thus seemingly gave the McIntoshes the right to the judicial "proceedings" that the "common law" would have provided. Story, supra, § 1783, at 661. This right presumptively included the need for a court finding at some point that the home qualified as a nuisance under the local ordinance. As one state court suggested shortly after the Fourteenth Amendment's adoption, "[t]he authority to decide when a nuisance exists, is an authority to find facts, to estimate their force, and to apply rules of law to the case thus made. This is a judicial function[.]" Hutton v. City of Camden, 39 N.J.L. 122, 129–30 (N.J. 1876) (emphasis added). Many more cases support this "fundamental" point "that the declaration of a nuisance is a proceeding of a judicial nature" and that municipalities cannot simply "declare that to be a nuisance which is not such" under the governing law. John B. Uhle, Summary Condemnation of Nuisances, 39 Am. L. Reg. 157, 160, 164 (Mar. 1891).

To be sure, the Due Process Clause contains exceptions to this "constitutional baseline" requiring executive officials to initiate court proceedings before depriving individuals of property. Jarkesy, 144 S. Ct. at 2145 (Gorsuch, J., concurring). In Murray's Lessee itself, the Court recognized one such exception for proceedings against federal tax collectors. 59 U.S. at 277. It explained that the common law had long allowed "a summary method for the recovery of debts due the crown," particularly "those due from receivers of the revenues." Id. And although the parties have not briefed the question, I suspect that another exception might allow executive officials "to summarily destroy or remove nuisances" in emergency situations when the nuisances threaten public health or safety. Uhle, supra, at 159 (quoting Lawton v. Steele, 119 N.Y. 226, 235 (1890)). As the majority opinion notes, however, the city officials here have not suggested that any emergency existed when they destroyed the mobile home. Nor have the city officials pointed to any other historically based exception to the constitutional baseline.

So how can the officials argue that their proposals (allowing the McIntoshes to negotiate with the building inspector or appeal to a city attorney) gave the couple "due process of law"? According to these officials, their actions comported with the Due Process Clause under the modern "balancing" approach to due process from cases like Mathews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319 (1976), and Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970). In Goldberg, the Supreme Court expanded the reach of the Due Process Clause beyond the "traditional common-law concepts of property" to cover new "property" interests—such as the interest in welfare payments. 397 U.S. at 261–62 & n.8; see Bd. of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564, 571–72 (1972). But this expansion would have created massive burdens if the Court had kept to the traditional meaning of "due process of law" by requiring judicial proceedings before depriving individuals of these new forms of "property." So the Court also watered down the right's traditional protections by holding that the guaranteed process "need not take the form of a judicial or quasi-judicial trial." Goldberg, 397 U.S. at 266. Rather, the Court suggested that the government need only provide a "meaningful" hearing—with the judiciary deciding as a policy matter what process satisfied this "meaningful" benchmark. Id. at 267 (quoting Armstrong v. Manzo, 380 U.S. 545, 552 (1965)); see Easterbrook, supra, at 125. In Mathews, the Court distilled this policy-rooted inquiry into its modern balancing test that decides the proper procedures based on the private and public interests at stake and the risk of "an erroneous deprivation" from the process that the government provided. 424 U.S. at 335.

Applying this balancing test here, the district court held that the city officials provided "constitutionally adequate" process because, among other reasons, they had "determined" that the home qualified as a nuisance. McIntosh, 2024 WL 1288233, at *6. So the court read the balancing test to sanction the destruction of traditional property based on nothing more than an executive official's say-so. This case thus shows how a court-created expansion of a right can lead to its contraction. The "minimal version" of the Due Process Clause that the Supreme Court adopted for new interests that would not normally trigger its protections becomes "legitimized," and lower courts then gradually apply this minimal version to interests that do fall within the clause's core. Philip Hamburger, Purchasing Submission: Conditions, Power, and Freedom 186 (2021).

We should exercise caution before taking this course. At the least, we should apply this modern balancing test in a way that allows for the "preservation of past rights," as the Court has done in other contexts. United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. 400, 407–08 (2012). When the "private interest" at stake qualifies as a traditional private right, perhaps the traditional process due should become the default process due under the modern balancing approach. Mathews, 424 U.S. at 335. And the government must show that the process it provided at least matches the protections provided by this traditional process. Cf. Pacific Mut. Life Ins. v. Haslip, 499 U.S. 1, 31 (1991) (Scalia, J., concurring in the judgment) (discussing Hurtado v. California, 110 U.S. 516 (1884)). Because Chief Judge Sutton persuasively explains why the processes that the city officials provided here did not meet this test, I am pleased to concur in the majority opinion.

The post What Process Is Due Before Property Is Destroyed? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Will Trump Make An Article II Override Argument To Justify Firing IGs Without Providing 30 Days Notice?

On Friday, President Trump fired about a dozen Inspectors General. These inspector generals are nominated by the President, and confirmed by the Senate. But the President's removal power is restricted through a notification requirement. 5 U.S.C. § 403(b) provides:

(b) Removal or Transfer.-An Inspector General may be removed from office by the President. If an Inspector General is removed from office or is transferred to another position or location within an establishment, the President shall communicate in writing the reasons for any such removal or transfer to both Houses of Congress, not later than 30 days before the removal or transfer. Nothing in this subsection shall prohibit a personnel action otherwise authorized by law, other than transfer or removal.

Trump clearly did not provide thirty days notice--doing so would have been impossible, since his term began only five days earlier. (Has it only been five days, feels like forever!?) Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, a champion of IGs, stated the obvious:

"There may be good reason the I.G.s were fired," Mr. Grassley said, referring to the inspectors general. "We need to know that, if so. I'd like further explanation from President Trump. Regardless, the 30-day detailed notice of removal that the law demands was not provided to Congress."

What is Trump's justification for not providing the notification? Maybe the restriction can't be applied to a new President who has just come into office? Does Trump think that the thirty-day clock infringe on his Article II removal power? Is he daring one of the IGs to sue him, to set up a Supreme Court test case?

Trump's refusal to provide notification brings to mind the Bowe Bergdahl situation. The National Defense Authorization Act required the executive branch to provide Congress with thirty-days advance notice before transferring certain detainees from Guantanamo Bay. But in 2014, President Obama did not provide advance notice before he transferred detainees in exchange for Bowe Bergdhal, an American POW. At the time, these released detainees were part of a trade to bring back Bowe Bergdahl. The Government Accountability Office concluded that the transfer violated "clear and unambiguous Law" and violated the "Antideficiency Act." How did Obama get around this statute?

The Obama Administration offered several defenses for the decision. Initially, at least, the Executive Branch said that the thirty-day restriction infringed on the President's Article II powers. I wrote about the constitutional issues with the release in an unpublished article:

Initially, Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel justified the release on the President's inherent Article II powers, as a rationale for his failure to comply with the law: "we believe that the president of the United States is commander in chief, [and] has the power and authority to make the decision that he did under Article II of the Constitution." White House National Security Adviser Susan Rice—a Sunday-morning show stalwart—similarly alluded to the President's inherent powers during an interview on This Week, "We had reason to be concerned that this was an urgent and an acute situation, that his life could have been at risk. We did not have 30 days to wait. And had we waited and lost him, I don't think anybody would have forgiven the United States government."

Alas, the anti-Article II Obama Administration walked back that statement.

Shortly thereafter, the Administration attempted to walk back that position, and the National Security Council released a more refined statement, not based on inherent powers: the "Administration determined that the notification requirement should be construed not to apply to this unique set of circumstances." Further, "Because such interference would significantly alter the balance between Congress and the President, and could even raise constitutional concerns, we believe it is fair to conclude that Congress did not intend that the Administration would be barred from taking the action it did in these circumstances." The White House Press Secretary likewise explained, "The administration determined that given the unique and exigent circumstances, such a transfer should go forward notwithstanding the notice requirement of the NDAA, because of the circumstances."

At the time, Jack Goldsmith eviscerated this rationale.

We will see what positions Trump put forward for disregarding the 30-day notice requirement.

Update: In 2022, Congress amended the statute to also require the President to provide "substantive rationale, including detailed and case-specific reasons" why an Inspector General was removed. This isn't quite a "for cause" removal standard, but it comes close. The President cannot say "I lost confidence" or some such general statement.

Trump did not comply with the 30-day notice requirement, and did not provide any rationales, let alone substantive rationales.

This issue was also a hot topic on the Sunday news programs:

Sen. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., on Sunday blasted President Donald Trump for his decision to fire 18 inspectors general late Friday night and accused the president of breaking the law.

"To write off this clear violation of law by saying, 'Well,' that 'technically, he broke law.' Yeah, he broke the law," Schiff told NBC News' "Meet the Press."

His comment was responding to Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., who earlier in the program told "Meet the Press" moderator Kristen Welker that "technically, yeah," Trump had violated the Inspector General Act, which Congress amended to strengthen protections from undue termination for inspectors general.

"I'm not, you know, losing a whole lot of sleep that he wants to change the personnel out. I just want to make sure that he gets off to a good start," Graham added.

In a later interview on CNN, Graham defended Trump more forcefully, saying, "Yes, I think he should have done that."

"He feels like the government hasn't worked very well for the American people. These watchdog folks did a pretty lousy job. He wants some new eyes on Washington. And that makes sense to me," he added.

But Schiff pushed back on that notion, warning that "if we don't have good and independent inspector generals, we are going to see a swamp refill."

He added, "It may be the president's goal here … to remove anyone that's going to call the public attention to his malfeasance."

The White House has not yet commented on the justification for the removal:

On Saturday, a White House official told NBC News that a lot of the firing decisions happen with "legal counsel looking over them." But they added they were checking with the White House counsel's office, though they didn't think the administration had broken any laws.

It's not clear how Congress can address this apparent violation of the law, but on Sunday, Schiff said, "We have the power of the purse. We have the power right now to confirm or not confirm people for Cabinet positions that control agencies or would control agencies whose inspector generals have just been fired."

The post Will Trump Make An Article II Override Argument To Justify Firing IGs Without Providing 30 Days Notice? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: January 26, 1832

1/26/1832: Justice George Shiras Jr.'s birthday.

Justice George Shiras Jr.

Justice George Shiras Jr.The post Today in Supreme Court History: January 26, 1832 appeared first on Reason.com.

January 25, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Further Thoughts on Justice Barrett's Recusal in Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board v. Drummond

On Friday afternoon, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Oklahoma Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board v. Drummond, and the companion case, St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School. Shortly before sundown, I dashed off a fairly-rushed post that considered why Justice Barrett may have recused. After some reflection, I will provide further thoughts.

St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School is represented by lawyers from Dechert, Perri Dunn (an Oklahoma Law Firm), and the Notre Dame Religious Liberty Clinic. Justice Barrett is an adjunct professor at Notre Dame Law School. In 2023, she earned nearly $15,000 from the law school. If Notre Dame University was a party, Barrett's affiliation with the University would trigger a recusal. (Justice Jackson, for example, sort-of-recused from the Harvard affirmative action case because she was on the Harvard Board of Overseers.) In theory at least, a ruling for, or against Notre Dame University could affect Barrett's employer's bottom line. But I do not think that a clinic affiliated with the school is sufficient to trigger a recusal. Moreover, Justice Kavanaugh was also an adjunct at Notre Dame in 2023, earning $25,000. And Kavanaugh did not recuse from the Oklahoma case. Many others judges also adjunct at Notre Dame; I do not think they have recused when the clinic has filed briefs in the circuit courts.

But we're not quite done with the clinic. Nicole and Rick Garnett are both faculty fellows to that clinic, but their names do not appear anywhere on the briefs. It is possible that the Garnett's connection to the clinic might not trigger Kavanaugh's recusal, but would trigger Barrett's recusal.

It is public knowledge that the Barretts and Garnett are extremely close friends. Barrett is the godmother of one of the Garnett's children. Indeed, in 2023 ABC News made a fuss that Barrett co-hosted a baby shower for Nicole Garnett at the Supreme Court in the Justices' spouse' dining room. ABC News raised this point in the context of the Notre Dame Clinic's amicus brief in Groff v. Dejoy, with the suggestion that Barrett had close ties. The suggestion was that Barrett should have recused from the case.

Did Barrett recuse because her dear friends were advisors to the clinic? If so, that recusal risk would pervade every single case the clinic works on. I deeply respect the clinic, and the work that they do. But it needs to be said that in any religious liberty case that could make it to the Supreme Court, Justice Barrett's vote is likely needed. And there is no way to know, ex ante, which case may go upstairs. Indeed, there are already many such cases in the pipeline that could trigger Barrett's recusal.

Then again, maybe the Garnett's affiliation with the clinic was not the cause of the recusal. The clinic has filed several Supreme Court amicus briefs, including in Groff v. DeJoy and Kennedy v. Bremerton, without triggering Barrett's recusal. On the lower courts, the filing of an amicus brief will trigger a recusal. FRAP 29(a)(2) permit striking a brief that could cause a recusal. I do not think the filing of an amicus brief would trigger recusal. If so, it would be too easy for malicious parties to file conflicting amicus briefs to knock a justice off the case.

The other possibility is that Barrett recused because Nicole Garnett has advised St. Isidore's. The New York Times stated that Garnett "helped advise St. Isidore's organizers." And Reuters stated that Garnett "has provided legal representation to the school's organizers." The Clinic also helped to organize the charter school in 2023:

In an interview with The Observer, Nicole Garnett, the Associate Dean for External Engagement at the Law School and a Professor of Law, explained that, "every state that has charter schools – there's 45 – prohibits them from being religious."

At this point St. Isidore reached out to the Notre Dame Religious Liberty Clinic for legal aid and for help organizing the school, Farley said.

"The dioceses in Oklahoma knew about the Clinic … so they reached out and said, 'We're thinking about this. What do you think?'" Garnett recounted. "I had already been writing quite a bit about religious charter schools, so it was a natural fit for us to take that work on." . . .

Farley specifically pointed to Nicole Garnett and John Meiser, Notre Dame Law Professor and Director of the Religious Liberty Clinic, as being crucial to helping the school's legal case. "We really wouldn't have been able to do what we've done without their assistance."

None of this information was in the briefs. Garnett's name does not appear in the "parties to the proceeding" section. Nor was this information in the corporate disclosure statement. Barrett must have known about this because Barrett had personal knowledge.

Recusal is triggered if a close family member is a party in the case, but I do not think "Godmother" to a person's child would count. Recusal is a very personal decision. My guess is that Barrett recused because her best friend was one of the people who advised St. Isidore's, even if Garnett is not a party, and was not involved in the current litigation. I don't think any rule or cannon would have required Barrett to recuse. But she herself may not have thought she could adjudicate this case fairly in light of her relationship with the Garnetts. That is, could she rule fairly concerning the institution her best friend organized and has publicly defended? (Before cert was granted, I predicted that the cautious Barrett would vote to affirm the Oklahoma Supreme Court.) Barrett's participation may have also attracted some public scrutiny, in light of the ABC News story after Groff. And Barrett has now avoided that scrutiny

At bottom, we do not know why Justice Barrett recused, as she did not explain the reason for her recusal. The unexplained recusal is really the worst of all worlds, because of the uncertainty it creates for the future. What is this uncertainty, you may ask? So long as the Garnetts are affiliated with the clinic, clients may fear hiring the clinic to avoid risking Barrett's recusal. I think the clinic's participation as an amicus is fine, but client representation is a different matter. Worse still, any legal work that the Garnetts have already touched, or will touch, may trigger Barrett's recusal down the road. Rational clients then may decide to not involve the Garnetts in order to ensure a full complement of Justices on the bench. None of these options are good.

This is not a pleasant post for me to write. I hold Nicole and Rick Garnett in the highest esteem. They have always been so gracious to me, and to everyone else in academia. Unlike most professors, who try to stay out of the limelight, the Garnetts lean into it. Their scholarship is not esoteric, but is impactful. I wish more professors could follow the model set by the Garnetts. And their work on St. Isidore is so important. This charter school, in particular, could be a paradigm shifting institution for religious instruction. Yet, there is a perverse tradeoff now. Any case that intimately involves the Garnett, should it reach the Supreme Court, might trigger a recusal risk. Maybe Justice Barrett will recuse, maybe she will not. But when planning a case ex ante, there is no way to know for certain what will happen. The rational course would be to avoid any possible recusal risk, even if that means walling off the Garnetts. Again, this is not a pleasant post for me to write, because we would all be poorer for not having the Garnetts influence cases of public concern. Justice Barrett's recusal, and failure to explain why, has allowed this uncertainty to percolate.

Finally, Barrett's recusal will create some uncomfortable situations for Justices Thomas in particular. He has not recused from cases tangentially connected to Harlan Crow, because Crow was not a party, and there is no rule that you must recuse because a friend may be affected by a case. Justice Scalia's non-recusal in the Dick Cheney case speaks to this issue. But now Justice Barrett has put forward a new standard that recusal is required if a close friend may be affected by a case, even if that friend is neither counsel nor a party to this case. This rule was novel, and potentially sets a new precedent.

The post Further Thoughts on Justice Barrett's Recusal in Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board v. Drummond appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Inside State-Run 'Bias-Response Hotlines,' Where Fellow Citizens Can Report Your 'Offensive Joke'"

An interesting story by Aaron Sibarium in the Washington Free Beacon. It offers a good deal of fairly concrete detail, always helpful in such analyses.

Such hotlines aren't themselves First Amendment violations, of course, unless they lead to coercive or discriminatory action against constitutionally protected speech, or at least the threat of such action. Even if they create something of a chilling effect on some people who don't want to get reported (or don't want to get reported again), that by itself isn't enough to violate the First Amendment.

Still, they do create possibilities for abuse, for instance if the resulting data is indeed at some point used to threaten the accused speakers (or deny them jobs or other opportunities). And I think they tend to create unrealistic expectations: After all, if the state says it wants you to report certain behavior, and tells you that it's bad behavior and that you're the victim of such bad behavior, wouldn't you expect that the state will actually try to do something about it?

Then when the state doesn't do anything, you might well feel let down: "Why isn't the state protecting me from this thing that it views as so bad?" Indeed, by framing certain incidents as bad enough to call for government response lines and then doing nothing about those incidents, the state may be exacerbating the initial offense that the callers felt at the incident, rather than ameliorating it.

And it might promote further reactions, such as litigation seeking restraining orders (even when that litigation ultimately goes nowhere, because the speech is constitutionally protected). After all, once authoritative institutions tell you that someone isn't just offending you or being a jerk, but violating (or at least jeopardizing) your civil rights, what kind of chump are you for doing nothing about that behavior?

To be sure, public reporting of suspicious or potentially criminal behavior can be good, even if the reports sometimes come to nothing. If I report that my neighbor's children have bruises, it might just stem from their having fallen while playing or it might stem from their having been beaten. It makes sense to have specialists investigate that, even if of course sometimes they too can make errors (and the investigation itself can feel intrusive to people who are wrongly suspected). I'm no fan of anti-"snitching" rhetoric that suggests that it's bad for people to report even genuinely criminal, or genuinely suspicious, behavior.

Likewise, if I report that someone is talking about how he wants to shoot up some sort of place, it's possible that I misunderstood a joke as something serious, and it's possible that the statement is too general to be a criminally punishable threat. But it's also possible that the person is indeed planning a very serious crime, and it's good to prevent that rather than to wait until it takes place.

But here I think the express call for reporting speech simply because of the viewpoint it expresses, not as part of an investigation of a possible crime or of an intention to commit a crime, strikes me as unsound and dangerous. Again, it's not itself unconstitutional, but it's also not something that I think our government ought to be doing.

The post "Inside State-Run 'Bias-Response Hotlines,' Where Fellow Citizens Can Report Your 'Offensive Joke'" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: January 25, 1819

1/25/1819: Thomas Jefferson charters the University of Virginia. 176 years later, the Supreme Court would decide Rosenberger v. Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia (1995).

The Rehnquist Court

The Rehnquist CourtThe post Today in Supreme Court History: January 25, 1819 appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers