Robin D. Laws's Blog, page 85

March 8, 2012

The Brain Printer

A Ripped From the Headlines Scenario Hook for Ashen Stars

A Ripped From the Headlines Scenario Hook for Ashen Stars

In a development that raises the prospect of bespoke organs created with cells extruded through a 3D printer, a patient in a June 2011 procedure received a new windpipe grown specifically for him. 3D scanning technology provided the template for an exact replica of his original windpipe, sculpted from polymer around a glass mold.

In the future timeline of Ashen Stars, the utopian space empire known as the Combine once assiduously policed its ban on sentient-species cloning. Like so much else, this has fallen by the wayside in the frontier region of the Bleed. But so far it's proven impossible to create true replicas of intelligent beings—you can make a physical copy, and even age it, but you can't recreate all of the experiences that shape personal identity.

That may have changed, the lasers discover, when they get the terms of their latest contract. Famed inventor Sian Sar hires them to track down her ex-husband, Rog Trainor, who, without her knowledge, used her own scanning technology to make a complete cellular scan of her brain. She believes that he's printed out a meat version of her brain, and is using it for competitive advantage—putting her genius to work on the same technologies her company is feverishly developing. Their mission: to bring Trainor to justice, and destroy the counterfeit of her brain.

The twist: Trainor has not only grown a replica of his ex-wife's brain, but installed it in a clone copy of her body. The result is a new person, who shares Sar's experiences and personality up to a point, but then diverged. She may not want to remain imprisoned and working for Trainor, but she doesn't want to be murdered, either. Do the lasers fulfill their contract, or accept her claims of full personhood?

March 7, 2012

It's the Squares, Man

Over at Gameplaywright, friend of the blog Will Hindmarch raises a discontinuity in RPG argument:

Over at Gameplaywright, friend of the blog Will Hindmarch raises a discontinuity in RPG argument:

This discontinuity in arguments about RPGs fascinates me: miniatures-based situations get in the way of RP and narrative, apparently, while games encouraging players to draw frequent maps and diagrams do not. What is it about molded plastic figures or the precision of measured spaces that clogs the gears of narrative?

I ask as someone who did not use miniatures in any RPG capacity until D&D3.x and has found plenty of fuel and clarity for both narrative and roleplay in games with and without miniatures. Why is a map okay until we set miniatures on it?

Without buying into the idea that the play style facilitated by one set of design decisions can be objectively superior to those fostered by another, I do think a perceptual shift occurs when you go from map to battlemap. Costs and benefits pertain to this shift, and it's up to the designer to take them into account in pursuing the game's design goals.

Your classic hand-drawn dungeon map, either drawn by players or received as a handout, serves as a reference point for further visualization. When you hold it in your hand, you're using it to picture the scene in your mind's eye.

A battle map, rolled out or drawn by the GM on a table, shifts everyone's visual focus from parallel visualizations to the representation everybody sees. If the group gets up from chairs set up around the room to stand over a table, that shift in physical position acts as a hard break between one mode of play and another.

The brain's bias toward the figurative emphasizes this when miniatures hit the table. We're keyed to respond powerfully to images of people, no matter how crude. Minis further shift us from an imaginative picture to a literal one, from interior vision to exterior object. As dramatic as this effect may be, I'd argue that it's not the biggest issue

I'd argue that the most powerful difference arises from the importance of squares to any battlemap. An old school dungeon map may be drawn on graph paper, but its squares act only as an aid to the drawing hand. On the battlemap, they become tactically active, adding a board game component to the RPG experience. The focus shifts from visualization to making the right plays, many of which revolve around positioning, with the number of squares one can move another resource to be cleverly managed over the course of a fight.

It's not the shift between maps to maps with minis that lies at the heart of this issue. It's the jump from map to board.

March 6, 2012

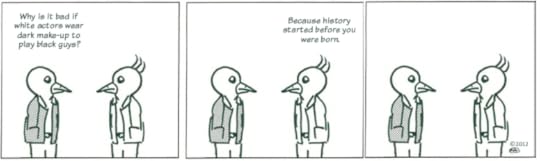

The Birds: Make-Up

March 5, 2012

When Laws Collide

[image error]When adding a new rule to a game, the designer must consider how it interacts with the game's other systems. One major task of playtesting is to find the surprise interactions between seemingly unrelated rules, and eliminate them.

Legislators, and the bureaucrats who interpret the various laws they pass, suffer no such limitations. Here's a bizarre example of a collision between two unrelated statutes that suggests that Congress ought to playtest more efficiently before succumbing to rules bloat.

The estate of art dealer Ileana Sonnenbend is suing the IRS to reverse a ruling valuing a famous Robert Rauschenberg collage/painting, "Canyon", at $65 million for inheritance tax purposes. The problem? "Canyon" famously features the taxidermied wings of a bald eagle, rendering its sale illegal under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. This law predates the creation of the piece; Rauschenberg was breaking it when he made the work. It can't even be exhibited without a special permit.

Sonnenbend valued it at $0. The IRS argued otherwise. They regularly levy taxes on illegal items, including stolen goods. In this case, they're telling the estate that it could sell "Canyon" on the black market, perhaps to a "reclusive billionaire in China," and thus owes them a masterpiece-based rate. The taxman is all but telling executors to go ahead and break that pesky, non-remunerative other law. Hey, it's only enforced by those wussies at the Fish and Wildlife Service.

With no GM to decide which rule takes precedence, estate lawyers have made an appointment with the next best thing—a US tax court judge.

March 2, 2012

I Should've Remembered I Should've Said

Tyler at Held Action does me the great service of unpacking an idea I floated back at the Dragonmeet "Ask Ken and Robin and Simon panel." It's a thought so brilliant I totally forgot making it: that the player choice to spend investigative points in GUMSHOE can be likened to the improv game of "Should've Said." In the game, the performers create a scene, and audience members can yells out "Should've Said" when a line isn't cool enough. The actor then rewinds and supplies what is hopefully a funnier line.

Tyler at Held Action does me the great service of unpacking an idea I floated back at the Dragonmeet "Ask Ken and Robin and Simon panel." It's a thought so brilliant I totally forgot making it: that the player choice to spend investigative points in GUMSHOE can be likened to the improv game of "Should've Said." In the game, the performers create a scene, and audience members can yells out "Should've Said" when a line isn't cool enough. The actor then rewinds and supplies what is hopefully a funnier line.

Tyler notes that this idea can be extended to any game with a hero or drama point mechanic:

When a player spends a point, they're really saying, "Change up what you're saying."With drama points, that change-up is probably to do with the player not being happy with what the GM's saying: "Your character takes a blow to the head" or "You don't find anything of interest in the warlock's study." If they're spending points, they're not happy about something. Outside of the immediate redress of "Oh, it was a glancing wound," I think it's a good mindset to take those spends as an opportunity to ramp up engagement by giving them exceptional carrots.

In expanding this idea, Tyler has hit on a helpful way of understanding ability points in GUMSHOE. In a sense, they really do represent a targeted drama point system, in which you get lots of points to spend in different situations that, through action, reveal your character's key traits.

March 1, 2012

Tragedy of the Meaty Commons

A Chicxulub-intensity extinction event is headed for my dinner table, and it lands on April 7. European Quality Meats, the butcher shop I've been frequenting for the last fifteen years, is slated to close, a casualty of gentrification. Established half a century ago, it's a fixture of a key Toronto location, Kensington Market. This matrix of independent shops shows the marks of successive waves of immigration. For a hundred years it's been the place freshly arrived communities gravitate towards, leaving stores and restaurants behind even when they become prosperous and move elsewhere. From Jewish to Portuguese, from Caribbean to Tibetan, its businesses are the Toronto I love in microcosm. Kensington likewise mirrors the history of alternative culture in the city, from the used clothing shops of the 80s to the artisanal coffee and charcuterie joints of the present moment.

A Chicxulub-intensity extinction event is headed for my dinner table, and it lands on April 7. European Quality Meats, the butcher shop I've been frequenting for the last fifteen years, is slated to close, a casualty of gentrification. Established half a century ago, it's a fixture of a key Toronto location, Kensington Market. This matrix of independent shops shows the marks of successive waves of immigration. For a hundred years it's been the place freshly arrived communities gravitate towards, leaving stores and restaurants behind even when they become prosperous and move elsewhere. From Jewish to Portuguese, from Caribbean to Tibetan, its businesses are the Toronto I love in microcosm. Kensington likewise mirrors the history of alternative culture in the city, from the used clothing shops of the 80s to the artisanal coffee and charcuterie joints of the present moment.

With one or two exceptions, chain stores have failed to gain a foothold here. Despite the odds, Kensington remains a vibrant oasis of local culture. Two things about oases: they're delicate, and people fight over them. Conflicts bubble between residents and park squatters, between proponents and opponents of car-free summer festivals.

Were I cruelly tricked into telling an evil mastermind how to wreck the market, European Quality Meats is exactly the jenga tile I'd tell him to knock out. The nabe is served by a few other meat purveyors, from the cutting edge to the poky and old-school, but none can handle EQM's volume, or deliver its balance of value and, well, quality. What happens to Kensington's shops of other categories, like produce, seafood, cheese, bulk food, and manifold national specialties, if you can't really buy everyday meat there anymore?

It's hard to begrudge any owner of a longtime family business for cashing out, selling the property, and pocketing $1.8 million—even when they aren't septuagenarian Holocaust survivors like European Meats founder Morris Leider. A business isn't a heritage site, no matter how much it may anchor the neighborhood around it.

That building is worth nearly two mil because it's in Kensington. And Kensington is Kensington because of its key commercial institutions, European Quality Meats foremost among them. You couldn't ask for a more frustrating example of gentrification's core irony.

February 29, 2012

The Birds: Communication

February 28, 2012

The Once and Future Vice-President

A Ripped From the History Books scenario premise for Trail of Cthulhu

A Ripped From the History Books scenario premise for Trail of Cthulhu

It is 1936. Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace, hailed for his New Deal innovations, is easily the most mystical of cabinet secretary in US history. A self-proclaimed spiritual seeker of Theosophist bent, he openly connects his occult beliefs to his liberal politics. He even convinced fellow mason Franklin Roosevelt to pluck the Great Seal, with its eye and pyramid design, from obscurity to a new spot on the back of the dollar bill.

Neither man knows it yet, but in four years Wallace will become Vice-President. Someone who does know this is the New England dowser and sorcerer Eliphas Haslam, who has learned to perceive non-linear time. Using spells of soul migration acquired from Joseph Curwen, the terminally cancer-ridden Haslam aims to possess a new body before his old one dies.

Both he, Wallace and at least one of the PCs are on the guest list of a seeker's conference outside Arkham. The action begins when a car crashes into a telephone pole outside the resort hotel where the conference is convening. Haslam, the sole passenger, is dead inside the car—but impossibly, seems to have been dead for hours!

The horrible truth is that Haslam managed to anchor his soul in his dead body long enough to reach the conference and migrate his soul to another of the guests. (The spell only works on hosts who have opened themselves to occult perception—which includes not only every participant at the conference, but any PC with a rating in Occult or Cthulhu Mythos.) He'd hoped to take Wallace's body, so he could ride it to the coming Vice-Presidency, then kill Roosevelt and become President. But, despite the setback, the weekend is young, Wallace is still at hand, and Haslam may yet body-hop his way to the White House.

February 27, 2012

Core Book Structure

Or, How To Design RPGs the Robin Laws Way (Part Five of Several; see part one for introduction and disclaimer)

Or, How To Design RPGs the Robin Laws Way (Part Five of Several; see part one for introduction and disclaimer)

Having determined the core activity and design throughline, I outline, and thus structure, the book. I ask myself first of all if either of the fundamental elements call for a nonstandard structure. If not, I start with a chapter order arising from the idea of a core activity. A roleplaying game is about the characters and what they do. Ergo, the book should start with character generation. Often this entails the provision of enough context about the setting to make decisions about the characters players are designing. So I likely kick off with a quick overview of the world, universe or what have you. The rest of the first section of the book follows the step-by-step of character generation. Into this process I try to build mirrors of the design throughline: the listed decisions, and the order in which you make them, arises from the core subject matter and emotional experience of the game. HeroQuest wants you think of your characters as part of a narrative and so (among alternate choices) asks you to start with a 100-word prose description of your character. DramaSystem focuses on drama and so asks you to first establish your role in relationship to other characters and the two opposing poles that will drive your actions. GUMSHOE privileges investigation over other activities and so presents the investigative abilities before the general ones.

Subsets of character generation then appear, from most to least important, from universal to those germane to only certain character types. Almost every designer does this, whether they articulate it this way or in some other manner they find intuitive.

After this come the core rules, which enable you to understand the stuff you've just written on your character sheet. For complex resolution systems an introductory precis may appear up top, with more detail later on, so that players understand enough to make good decisions.

After this I usually cover the setting material, because it's more fun to read, and perhaps more specific to the game, than explanatory material like GM support and play style advice. The further into a book I get, the less I expect players, rather than the GM, to grapple with its contents.

Then, if the game uses them, comes the sample adventure. Given the choice I try for as complete an example as possible. I look on the sample scenario as an extended play style example and setter of expectations. My feeling is that a truncated or perfunctory scenario that merely tries to teach you the rules is a missed opportunity at best and actively misleading at best.

Last come the appendices, reference sheets, and other bits of useful support material that aren't part of the body of the book per se.

Whether you order things like I do or not, the careful thought you pour into this question may not matter. A certain percentage of people jump around in roleplaying games to find the bits that most interest them, and then fill in the gaps. But even as they do so, they likely notice the structure and, subliminally if nothing else, learn what you're telling them from your placement order.

February 24, 2012

Momentum, With or Without Fiery Motorcycles

Okay, so I was stoked for a Neveldine / Taylor take on Ghost Rider. Here's how to enjoy Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance. Wait for DVD or another fast-forwardable medium. Skip every moment, except for those in which a) something is on fire or b) Nicolas Cage is delivering lines (voice over not included.)

Okay, so I was stoked for a Neveldine / Taylor take on Ghost Rider. Here's how to enjoy Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance. Wait for DVD or another fast-forwardable medium. Skip every moment, except for those in which a) something is on fire or b) Nicolas Cage is delivering lines (voice over not included.)

The goal of Johnny Blaze, like so many Marvel heroes, is to stop being the character we've signed up to see. He becomes a tag-a-long in his own movie, with the weirdo priest Moreau, played by Idris Elba, supplying most of the motivation. For a movie patterned on Terminator 2, in which the hero has to stop the devil from capturing a child, there's way too much explanation going on. In other words, the script, apparently cut down from a much more elaborate version predating the original film, sadly leaves the duck in.

It's still way better than the first one, low bar that this may be. The action is agreeably gonzo and there are some great gags. For additional entertainment value, imagine that this Johnny Blaze is not the guy from the first movie, but rather a cursed version of the Cage character from Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. Hey, they both went out with Eva Mendes.

I bring this up not to slag the movie, but to look to the lesson in narrative construction it provides. Films, action flicks in particular, live and die not only on the content of the set pieces, but on the momentum between scenes. Whether they build in one direction, or converge from two or more, it's the way the scenes connect that keep us engaged.

This doesn't apply only to films featuring flaming skull-headed vigilantes. The genius of Citizen Kane, and the propulsion it sustains despite its achronological story order, derives from the brilliance of its scene transitions.

Here lies a key distinction between movies and roleplaying sessions. In the latter, players value freedom of choice and action over momentum. They want to control the pace, often stopping to slow it down so they can go back and add interstitial action a screenwriter would cut to elide. For the GM, the trick is to ensure that the action moves a median pace that splits the difference between methodical players and those who prefer to keep it moving.