Robin D. Laws's Blog, page 120

February 2, 2011

The Birds

February 1, 2011

Watch the Trigger Fingers

Uprisings against authoritarian rulers become revolutions when the class tasked with the violent suppression of dissenters balks, refusing to murder on their leaders' behalf. The Chinese government put down the Tienanmen protesters by finding provincial army units who, unlike their Beijing counterparts, were willing to fire on them. The Iranian regime carefully cultivates and rewards its thugs, whether they be Bassiji or elite military units. Their enforcers get a cut of corruption along with their ideological indoctrination, ensuring that they had everything to lose if the Green Revolution won. So they went about their violent duties with cruel enthusiasm. A similar caste did similar dirty work in Burma.

The Tunisian army, on the other hand, was neglected and underfunded by its now-former leader.

It's the way that the strong-armers go, and not the use of social media or 21st century communications technology, that provides the tipping point between revolution and crackdown.

Rarely do you see an uprising in which the ultimate arm of suppression issues a press release announcing that they're not going to fire on anyone. The state security police aren't balking so far, but with protests as big as they've grown, they won't be able to do the job themselves. Any unfolding political crisis retains the potential to go horribly wrong. All official statements, not excluding those made by military officials in autocratic regimes, must be read with skepticism. Still, this gives reason for hope.

The biggest difference the Internet age will make in cases like Tunisia and (one hopes) Egypt comes afterward the regime crumbles. The 20 and 30-somethings who drive the early days of a revolution are today plugged into global culture. Moreover, that culture is, because of the Internet, more bottom-up, participatory, and egalitarian than it has ever been before. Power creeps back in, as power always does. But in the meantime the idealists might have the BS detectors they need to blunt the machinations of the predators and ideological scam artists who always show up to exploit a post-revolutionary power vacuum.

January 31, 2011

Fridge Pipe

The beat analysis system seen in Hamlet's Hit Points divides expositional moments into three major types. Question beats make us curious; reveals satisfy that curiosity, often in a surprising way. The third type is the pipe beat, which gives us information we'll need later. A classic pipe beat is unobtrusive, so as not to tip the reveal in advance. If, while experiencing a story, you find yourself thinking, "This apparently tangential detail will matter later," the pipe beat is giving itself away.

Some bits of information don't so much set up a reveal as support the story's logical framework. The line of dialogue that explains why the crew can't use the transporter to beam down to the planet allows us to accept a contrivance necessary for the plot of this week's episode.

If you find yourself writing a story, or plotting an RPG adventure, that requires a lot of this explanatory support, you may want to go back and streamline your way to a simpler, contrivance-light plot.

There's another form of pipe beat, though, one that provides a retrospective explanation that keeps the story credible in the light of its reveals. Alfred Hitchcock famously spoke of refrigerator logic: seeming plot holes that only become apparent when you think about a movie afterwards, while assembling your post-film snack at home later that night. Hitchcock wasn't so much worried about this stuff if it kept the in-the-moment experience compelling. In prose fiction, where the reader is free to skip back and check what you did five chapters ago, you probably want to keep your construction tighter than that. The advent of home video and Internet discussion forums mean that the screenwriter might be called to greater account for restrospective logic problems than he would be in Hitchcock's day.

Thus, a moment placed into a story so that it makes sense in retrospect would be fridge pipe. Let's say you have a character who suddenly betrays the hero at a crucial moment. Tight story logic requires that you look at all of the moments and make sure that all of his scenes fit his real intentions rather than his apparent ones. If his ultimate goal is to kill somebody, and he forgoes up a chance to do so when we still think he's a good guy, the writer will likely lay in some fridge pipe. Later, you can return to that moment, ask why he didn't kill the hero in act one, and see that he was interrupted by his grandmother, hadn't yet collected the payment for the hit, or whatever. The beat serves the story, but only when looked in the retrospective glow of the refrigerator light.

The freeze frame era has made the hunt for refrigerator pipe part of the game. A great recent example comes from the "Cooperative Calligraphy" episode of Community. This self-aware bottle episode revolves around the hunt for a pen thief in the group. At the end (SPOILER) we discover that a monkey did it. Enterprising frame hunters discovered that the monkey steals the pen onscreen, in a moment that takes place at subliminal speed.

January 28, 2011

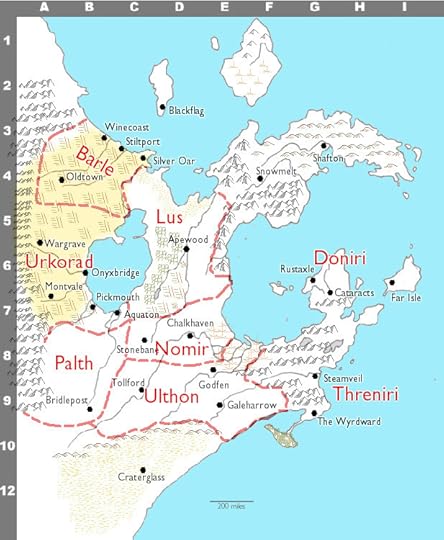

Korad: Nations Beneath the Skin of Empire

Before Korad was an empire, it was a continent, home to disparate nations, each steeped in its own language, history and culture. Eventually one nation, Urkorad, rose to dominate the others, imposing its rule and importing its ideology. Its language is the lingua franca; its beliefs the intellectual lifeblood of the ruling class. Yet underlying the official surface, the peoples of the other nations remain. National borders are today provincial dividing lines, but it may not always be that way. As crisis envelops the empire, they may become more important still. If it breaks apart, these are the fragments it will likely become.

Cities that not encircled by national boundaries are either independent or quasi-autonomous entities, like Far Isle, Blackflag and Craterglass. Or they were settled after the imperial period, like the settlements of the northern pincer. They are culturally Koradi, whatever their shifting political allegiances.

Last week we voted to choose the non-humans of Korad. They are:

* the Veytikka, carrion-eating humanoids, clawed, tribal, able to perceive across the veil of death (20% of the vote)

* Aesigils: Sentient, sapient runes, symbiotically bond with host creatures (14%)

* so-far unnamed independent, unionised beasts of burden. Heavy and hardy, between camels and rhinos. (11%)

To detail them further, we'll start by deciding which nations they once dominated.

Our intelligent beasts of burden don't seem as if they'd establish a polity and civilization without people. Barring persuasive rebuttal, I'm going to stipulate that they're a minority, albeit a sizeable one, wherever they appear. Further, their presence transcends national boundaries.

That leaves two nations to sign over to our non-humans. Urkorad, seed of the empire, is out of the running. That leaves Barle, Palth, Lus, Nomir, Ulthon, Doniri and Threniri as possible strongholds of the Veytikka and Aesigils (whose hosts are, presumably, predominantly human.)

View Poll: #1673682

View Poll: #1673683

If the same province wins both polls, the one for which the winner garners the most vote will be ruled in. The second place winner of the other poll will become the homeland of the corresponding non-human people.

Once the non-human nations are chosen, we'll go back and rationalize any apparent conflicts with the already established city descriptions.

The Korad setting bible is over on Scribd.

January 27, 2011

The Birds

January 26, 2011

The Most English Children's Book Title Ever

January 25, 2011

The Claudius Conundrum

I've been shirking a homework assignment. After a close read of Hamlet's Hit Points, ![[info]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380442897i/1319734.gif) nottheterritory wrote me to ask if I omitted a couple of seemingly important beats in Hamlet intentionally, or because I'm a big old bonehead.

nottheterritory wrote me to ask if I omitted a couple of seemingly important beats in Hamlet intentionally, or because I'm a big old bonehead.

Actually, he didn't say that last bit at all. He asked very kindly, as he is wont to do:

I notice that in the three .pdf versions, you do not cover either Claudius' "my offence is rank" or Hamlet's "now might I do it pat" soliloquies as beats. Indeed all the text versions of the play that I can find (and I admit I've only checked a few online) seem to differ with your structure of the play by placing those two soliloquies at the end of 3.iii and marking the scene in Gertrude's bed chamber as a new scene: 3.iv. I notice that you refer to the moment when discussing Hamlet and Gertrude in the bed chamber (3.3.C Hamlet Kills Polonius), writing:

"The upcoming scene where Hamlet approaches upon Claudius at prayer and vengefully decides not to kill him is of greater emotional, thematic and narrative importance than the earlier moment when Hamlet

makes fun of Polonius by getting him to agree that a cloud looks first like a camel, then like a weasel, then like a whale."

I'm assuming this suggests that you meant to mark those as beats since you're saying that (either singly or separately) they are more important than a moment you did mark as a beat (3.2.G – Hamlet Subjects Polonius to a Cloudy Jape). I also can't help but feel Claudius' admission of guilt qualifies as fairly big reveal!

As the mixed-up scene numbering suggest, this omission is just a plain old ordinary error on my part, committed during the original blogging process. I must have skipped around and never skipped back.

While the error doesn't undermine the RPG thesis of the book, it does mar the completeness of the Hamlet analysis.

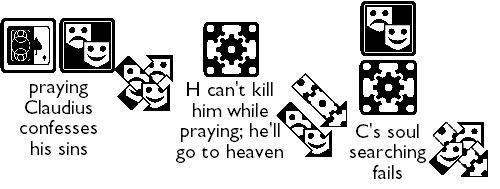

Claudius' soliloquy does play like a reveal, although as the play is usually staged it's more of a confirmation of what we already assume than a surprise. It does however introduce a troubling note of dramatic ambiguity. As audience members, we've been happily perceiving Claudius as an antagonist, and rooting for Hamlet as he pursues his program of investigation and retribution. Suddenly we're thrust into Claudius' mind, through the device of the soliloquy, the Elizabethan theatrical delivery system for internal monologue. Now we suddenly find ourselves feeling sympathy for the wrongdoer, even as he's confessing his crime. He is the petitioner, seeking forgiveness. Depending on how you want to look at it, the silent granter is either an offstage and characteristically unresponsive God, or Claudius' own conscience.The ambiguity of our conflicted emotional response calls for crossed dramatic arrows.

More disorienting still is Hamlet's reaction as her overhears Claudius pray. He realizes that he can't kill him now, because he's confessing and will therefore go to heaven despite his crimes. Hamlet has to give up his clear shot at his enemy, postponing until he can catch him committing "some act / That has no relish of salvation in it", and kill him in the certain knowledge that he's headed to hell. This loss of the clear shot is a procedural downbeat, as it stops him from completing his practical goal. It also registers as an emotional downbeat, as we come to doubt our protagonist. As on board as we might be with Hamlet's mission of vengeance, we may recoil from his cold-bloodedness as he games the the holy system.

Then, when he leaves, Shakespeare both twists the procedural knife, and relieves the audience's emotional discomfort. Claudius loses his own petition to himself (or God), and is unable to find contrition. It's a procedural downbeat: ironically, Hamlet could have killed him and sent him to hell, but has now lost the chance. Dramatically, we recover our vengeful equilibrium, and get to go back to sympathizing with Hamlet and anathematizing Claudius. The villain's distress is our satisfaction, as one half of another ambiguous beat.

January 24, 2011

McCarthy-Lovecraft

Need a topic for your next American lit term paper? I have a live one for you:

Cormac McCarthy as thematic heir to H. P. Lovecraft

Start by noting what seems like their diametrically opposed styles: Lovecraft's ornate, florid wordscape vs. McCarthy's equally stylized spareness. Then conclude that under these difference both have an incantatory technique which is as much about rhythm as meaning.

Then bring in the big theme: despite their different genres, both are apocalyptic visionaries. Central to each writer is a breakdown of meaning, especially the comforting assumptions of default morality.

Compare and contrast their treatment of moral and spiritual degeneracy. Link its appearance in "The Dunwich Horror" (or take your pick of a dozen other Lovecraft stories) to the Uncle Ellis sequence in No Country For Old Men. (The sheriff thinks that the events he's witnessing in his current case represent a sudden spiral into depravity. He visits an elderly ex-lawman whose tale of horrible past violence suggests that the horror is not new but atavistic, and always lurking just below the surface.)

Examine the unspecified post-doomsday of The Road as a continuation of "The Color Out of Space."

Wrap up by looking at McCarthy's entropic, post-moral devil figures, Anton Chigurh and the Judge from Blood Meridian, as analogues of Nyarlathotep.

For bonus points, determine whether McCarthy is remotely familiar with Lovecraft.

You're welcome.