Robin D. Laws's Blog, page 83

April 4, 2012

The Birds: Emergent

April 3, 2012

House Systems and Forced Fits

Regarding a previous post on why I don't repurpose discarded sub-systems, Chris Angelucci asks:

Regarding a previous post on why I don't repurpose discarded sub-systems, Chris Angelucci asks:

What does this mean for companies with "house systems?" Will any game concept end up being a forced-fit?

I'd argue that mostly this doesn't become the case, for a couple of reasons. House systems are often created by an RPG company's key designer, who then goes on to design, or influence, later iterations. The core rules think like that designer does, and so do its later expressions. So while you might not like Joe Green's take on superheroes, or think that the JoeGreenRules fit that genre well, they're likely internally consistent.

On a related point, the design concept is, explicitly or otherwise, to do the JoeGreenRules take on a new genre. The core audience for a rules platform wants to see what happens when it's applied to space opera, or swords 'n' sandals epics, or whatever. They're invested in that game and way of thinking already, and want to see a game that arises in the meeting point between the game rules they know and a genre they know. White Wolf fans aren't necessarily looking for the platonic ideal game about modern fairies, so much as they probably think the ideal game about fairies will be Changeling—a variation of the core rules and approach they already dig.

To cite a counterexample, the Ars Magica rule engine might not have been the ideal basis for Rune, the game of hyper-competitive, Viking mayhem I did for Atlas. But given that the concept itself was so far removed from anything that had been done before, and that it was a stretch for our timeline and playtesting resources, it was the right choice practically. To invent a new core engine, and make that work, and then make the GM-swapping, point build encounter superstructure also work on top of that, lay beyond our time budget.

If the call to adapt the Rune video game had come just a few years later, the D20 license would have been in play, which would have served the pragmatic aspect of the project and been a better fit. We'd likely have been able to draw from a bigger playtest pool and could maybe have sold enough copies to justify the long development window its ambition required.

April 2, 2012

Equinenimity

Sarah Monette applies her experience of real-life horses to list five ways in which the actual creature differs from its portrayal in fantasy fiction:

Sarah Monette applies her experience of real-life horses to list five ways in which the actual creature differs from its portrayal in fantasy fiction:

Diana Wynne Jones famously deduced that the horses of Fantasyland are vegetative bicycles. Here are some ways that real horses are anything but:

1. Horses are very large animals. This is something that you can know in the abstract, as we all do, and still be taken aback by when interacting with an actual horse. Horses take up space. Their heads are massive chunks of bone. Even when they're being affectionate, they're still a good eight to ten times larger than a human being, and they are proportionately stronger. [Read on...]

I am not a horse person and will totally cop to a nagging anxiety whenever I write a fantasy scene with riding in it. Sure that I will get called out for reality-defying nonsense, I keep the horses in the background to the maximum extent possible. Fortunately the latest novel is set in a city, with lots of walking and almost no horses testing its verisimilitude.

Another problem, though, is that real horses are disjunctive in most narratives. As Sarah describes, they're fragile and headstrong animals, both of which traits have a tendency to suddenly disrupt a protagonist's momentum. (A recent headline reinforces their fragility: the show Luck, in which that fragility was a major theme, has had to cease production after a string of horse deaths.) Well-constructed narratives don't provide much space for accidents or distractions. If an accident leads to a crucial plot development, it suddenly becomes a contrivance. If it exists only to show that accidents happen, it's failing the rule of fictional parsimony, which allows only for events that drive the story or in some other way relate to its overall throughline.

Hence the convention of the herbivorous bicycle.

March 30, 2012

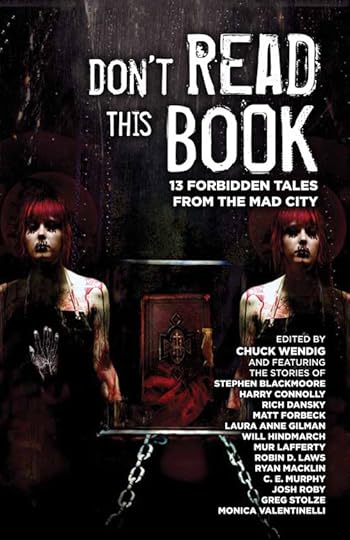

Don't Read This Book

Evil Hat has released the cover image for Don't Read This Book, its upcoming anthology of short fiction set in the Don't Rest Your Head game setting. The insomniac protagonists of DRYH slip from our world to a surreal parallel realm of gothic strangeness, fearing both that they will never sleep again and that they will awaken, losing their strange new powers. My contribution to the book, "Don't Lose Your Shit", tells the tale of a recent inductee into this unending night, as he discovers a weird convenience store on the head-pounding borderland of sleep and waking. There in its beverage refrigerator awaits a troubling array of unfamiliar energy drinks, which hold out the promise of both doom and salvation to its haunted and shuffling denizens.

Evil Hat has released the cover image for Don't Read This Book, its upcoming anthology of short fiction set in the Don't Rest Your Head game setting. The insomniac protagonists of DRYH slip from our world to a surreal parallel realm of gothic strangeness, fearing both that they will never sleep again and that they will awaken, losing their strange new powers. My contribution to the book, "Don't Lose Your Shit", tells the tale of a recent inductee into this unending night, as he discovers a weird convenience store on the head-pounding borderland of sleep and waking. There in its beverage refrigerator awaits a troubling array of unfamiliar energy drinks, which hold out the promise of both doom and salvation to its haunted and shuffling denizens.

Note the impressive roster of writers assembled by the book's editor, the fearless and peerless Chuck Wendig. I await announcement of a release date with hallucinatory fervor.

March 29, 2012

The Birds: Brno

March 28, 2012

The Leng Connection

A Ripped From the History Books Scenario Hook for Trail of Cthulhu

A Ripped From the History Books Scenario Hook for Trail of Cthulhu

The exact extent to which the 1938-39 Tibet expedition led by explorer Ernst Schafer served the Nazi agenda remains a matter of controversy. After the war, Schafer claimed to have come by his posting as an SS Hauptstrumfuhrer unwillingly. Also unclear is how successfully he derailed Himmler's goal for the trip—to have Ahnenerbe pseudoscientists measure Tibetan skulls in an attempt to prove that Siddhattha Gotama, the historical Buddha, had been an Aryan in good standing.

Perhaps the greatest mystery is what Himmler thought he stood to gain by proving this, given the incompatibility of Nazi ideology and Buddhist thought.

If we fictionalize it a little, though, we get a Trail of Cthulhu scenario of high altitude high adventure.

When a politically fervid fellow inquirer into the mythos conspiracy goes missing in Tibet, the investigators follow his trail. They discover his plan to infect Himmler's minions with contagious madness, by leading the Ahnenerbe to the Plateau of Leng. Do they help him destroy Nazi scum—or see the vast potential for backfire, and work to thwart him?

Source: Confession of a Buddhist Atheist, Stephen Batchelor

March 27, 2012

Disorienting Exposition

In fiction set in unfamiliar times and places, it often falls to the author to explain details of the world well-known to the characters but not to the reader. How straightforwardly to lay this out is a matter of style, and therefore taste. I tend to want to deliver it in a compact way and get on to the story it's supporting. Some readers prefer obscured approaches that take longer but don't necessarily signal themselves as expository—world detail through dialogue being a key technique.

In fiction set in unfamiliar times and places, it often falls to the author to explain details of the world well-known to the characters but not to the reader. How straightforwardly to lay this out is a matter of style, and therefore taste. I tend to want to deliver it in a compact way and get on to the story it's supporting. Some readers prefer obscured approaches that take longer but don't necessarily signal themselves as expository—world detail through dialogue being a key technique.

A more complex technique presents expository detail about the world as if addressing a reader already familiar with it. Most often you'll see this in SF novels. The narrator rattles off terms and describes situations without full explanatory context.

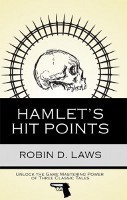

According to the beat analysis system found in Hamlet's Hit Points, these mystifying references serve as question beats. They arouse our anxiety and our curiosity, impelling us to read on, in search of clarification. As we figure out the world through additional context, we feel counterpointing up beats, when those questions are answered.

This might be seen as the SF version of a common literary fiction gambit, where details of the story being retold are teased but not fully laid out. In both cases these can substitute for the basic building blocks of most fiction, dramatic and procedural scenes.

How much one digs this is another matter of taste. Personally, I prefer to be invested in a character, to hope for her success and fear for her failure, before I'm asked to puzzle through an alien future. Other readers might be perfectly happy with pure world extrapolation, without all that pesky story and character always rearing its head.

March 26, 2012

Carts and Horses

Apropos of a previous post, Josh W asks: How often do you find yourself budding systems off and turning them into other distinct games? If it happens often enough, how do you deduce the design through-line that subsystem fits?

Apropos of a previous post, Josh W asks: How often do you find yourself budding systems off and turning them into other distinct games? If it happens often enough, how do you deduce the design through-line that subsystem fits?

For reasons implicit in your second question, this happens to me exactly never. I've certainly created sub-systems only to realize that they don't fit the design through-line. Usually they interpret the design goals too literally, or are disappear down a rabbit-hole of unnecessary simulation. Because of this, they are also usually flawed in and of themselves and thus go to the great discard pile in the sky.

Never have I accidentally created a rules subset that would work fine, if only I were working on a different game. In my view, building a game and its core activity around a nifty rules idea is a recipe for disaster. Start with the activity you think will make for engaging play, then facilitate that with rules that enable it in as simple and elegant a manner as possible.

Sometimes I do encounter games that feel like they sparked first from a system idea, with the core activity yoked in to serve it. If it even has a clear core activity. When you ask a designer to describe his game and he starts with a game mechanic, that's a warning sign of a game designed from an abstract rules concept outwards. (Or maybe he's just lousy at pitching.) For a few categories, like abstract games, design from sub-system out may be desirable. Often, though, you'll get the feeling during play that you are working for the rules rather than having them work for you.

March 23, 2012

The Birds: Happiness

March 22, 2012

Precisely Subjective

At Gaming as Women, Darla Magdalene-Shockley posits that subjective reward mechanics, dispensed for entertaining roleplaying, carry the risk of unconscious gender bias. Regarding actual play with Paranoia XP, she observes:

At Gaming as Women, Darla Magdalene-Shockley posits that subjective reward mechanics, dispensed for entertaining roleplaying, carry the risk of unconscious gender bias. Regarding actual play with Paranoia XP, she observes:

[W]e are all socialized very strongly to view women in certain ways. We expect women to be responsible, do the boring administrative work, and in general shut down the fun. We emphatically do not expect women to be silly. So women are less likely to be silly, and everyone is less likely to notice when they are. The Paranoia GM (despite being quite the stand-up guy) is less likely to notice and reward it.

Unexamined assumptions at the gaming table, including those surrounding gender, can certainly play havoc with what is meant to be a facilitator of gaming fun. Many people first came to RPGs as a structured way of overcoming shyness. Quiet, uncertain or casual players, whether they're that way out of socialization or inclination, or both, will get left behind by rules that do this—and maybe feel uncomfortably singled out when the GM takes compensating measures.

On the other hand, all games inevitably favor certain personal traits over others. The vast corpus of traditional games reward math savvy, recollection of complex rules, and willingness to spend time poring over rules text searching for optimal character build choices. In this context it hardly seems unreasonable that players with confident performance and improv skills will prosper in games falling on the story side of the spectrum.

A middle ground can be found by narrowing and defining the subjectively rewarded activity. The Dying Earth and its descendants, Skulduggery and The Gaean Reach (which I'm working on now), all mechanically encourage you to weaving taglines (supplied lines of dialogue) into the session. They bribe you to talk like Jack Vance's characters, an essential element in creating the feeling that you're exploring his worlds.

The GM does judge how effectively you use a given tagline, but by gauging the reactions of the group to your bon mots, which takes into account an observable, gestalt subjectivity if not objectivity. Where the instruction to "be entertaining" is broad and hard to define, the metrics for taglines are clear and simple. If, for whatever, reason you're less than voluble, taglines give you highly structured permission to seize spotlight time.