Kathy Joseph's Blog, page 9

April 30, 2022

Faraday’s Electromagnetic Wave Experiment: How One Experiment Defined Light

I was taught in high school that light is an electromagnetic wave. But what does that mean and how in the world was it discovered? This is a presumptuous college student, mysterious crystals, what polarizers are, and how polarizing sunglasses work. Ready? Let’s go.

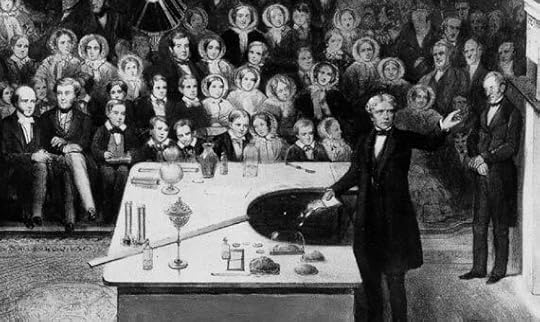

Fast-forward 17 years to 1845. Michael Faraday was 54 years old and was already famous for his discovery of the first motor, the ideas of magnetic fields, and induction as well as thousands of other discoveries. He also suffered from depression and memory problems (as well as possibly mercury poisoning, a common affliction for scientists at that time as they didn’t know the dangers of mercury) and was spending very little time in the laboratory. This is when a baby-faced 21-year-old mathematics student named William Thompson(later knighted Lord Kelvin) presumptuously asked Faraday if he had ever attempted to change something called the polarization of light with magnets or electricity while the light was moving through a transparent material. Faraday was intrigued, ever since Summerville’s disastrous experiment Faraday had been trying (and failing) to alter magnetism with visible light or to alter light with magnetism. He had even tried to change the polarization of light, but never while the light was in a material. Inspired, Faraday went back into the lab.

Michael Faraday

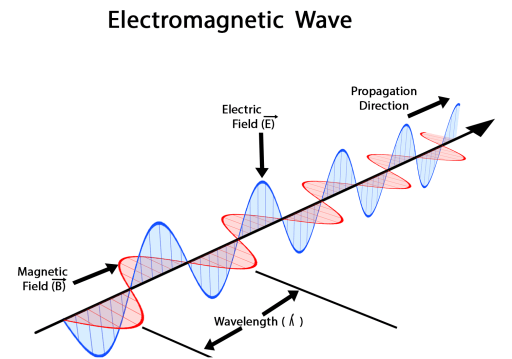

Michael FaradayNow, what is polarization? Imagine you are making a wave on a long rope. To make the wave you could move your hand up and down and the wave would move away from you down the rope. However, if you wish, you could also move your hand side to side. This direction of vibration is called the polarization of the wave. Now, most light is what is called unpolarized or randomly polarized, meaning that some is vibrating up and down, some side to side, and even some in clockwise and counterclockwise circles.

Now we come to a strange object called an “Iceland crystal”. When the light goes from air into a transparent material the light slows down and bends. For prisms, the amount the light bends is strongly dependent on the frequency of the light (the color), which is why prisms will split white light into a rainbow. Icelandic spar is unusual because the amount the light bends is dependent on the polarization of the light, not on the frequency. Therefore, when white light enters the crystal, it bends the light into two beams: one that vibrates vertically and one that vibrates horizontally. As humans can’t distinguish polarization with their naked eyes, the crystal makes two images.

In 1818, a man named David Brewster published an article that if light reflects off of a surface at a low angle (currently called Brewster’s angle) then all of the reflected light will be polarized parallel to the surface. If you look at this light with a properly oriented Iceland crystal you only got one image. This is why polarizing sunglasses work so well, they block the horizontally polarized light, which blocks the light reflected at low angles, also called glare.

Ten years later a Scottish scientist named William Nicol invented a device that was the last piece of the puzzle. Nicol wanted to make the Iceland crystal not just split the light into two polarizations, but actually, remove one polarization entirely – or make the first polarizing filter. He did this by cutting two crystals into triangles at very specific angles and then gluing them together. When light hits the crystal, the light splits into horizontally and vertically polarized light. However, the horizontally polarized light is bent more so that when it hits the glue all of the light is reflected (this is called total internal reflection) and shines out the side of the prism. The vertically polarized light, however, bends at the glue and then bends back into the glass on the other side of the glue and thus passes safely through the prism.

Now we have all of the pieces of Faraday’s experiment. Faraday shined light from the brightest lamp he could get at Brewster’s angle off of a piece of glass (getting horizontally polarized light). He then put a Nicol prism in the path of the light so that it filtered out the horizontally polarized light and he could no longer see the light from the lamp. Faraday then placed a strong electromagnet (magnet made with electricity) next to a sample of glass in the path of the light. When he magnetized the electromagnet he could see the light from the lamp! The magnetic field had rotated the polarization of the light! When he unplugged the electromagnet the image disappeared again. Faraday said that he had “established, I think for the first time, a true, direct relation and dependence between light and the magnetic and electric forces.”

Just as with Summersville, the scientific community was excited to hear that light and electricity, and magnetism was linked in, “one great universal principle”.

Faraday began thinking about what it meant to have light linked to electricity and magnetism.

The post Faraday’s Electromagnetic Wave Experiment: How One Experiment Defined Light appeared first on Kathy Loves Physics.

Who invented the Wireless Telegraph?

According to many people, Guglielmo Marconi invented the wireless telegraph. In fact, his name was so joined with wireless telegraphs that for many years’ telegraphs were called Marconigrams. However, he wasn’t the first to make wireless transmissions nor did he invent most of the devices he used in his experiments. How did this basically uneducated man make a telegraph empire, win a Nobel Prize, and destroy Nikolas Tesla’s life?

In the summer of 1894, a 20-year-old Irish-Italian man named Guglielmo Marconi read an obituary of Heinrich Hertz and was inspired to make the wireless telegraph go around the world. Marconi was oddly uneducated. I say odd because Marconi came from a very wealthy family: his father was Italian nobility and his mother was an heiress of the whiskey fortune from Jameson & Sons. However, Marconi’s Protestant mother didn’t want him to, “come into contact with the great superstition that is commonly taught to small children in Italy.” Therefore, Marconi was educated by a string of tutors who gave him a sporadic education that, with his Mother’s permission, skipped anything he didn’t like, including most math and physics!

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo MarconiThe obituary of Hertz mentioned Hertz’s greatest accomplishment: he created an invisible electromagnetic wave that traveled and acted as a light wave. In other words, Hertz discovered radio waves! Hertz had created a wave with an antenna attached to an induction coil and received it by looking at a teeny tiny spark in a ring receiver. If Marconi was going to use Hertzian waves to send long-distance wireless telegraphs then the first thing he needed was a better receiver. Luckily for Marconi, an Englishman named Oliver Lodge had found one.

Lodge had met Hertz and was profoundly sad to hear of his passing. To honor him, Lodge decided to give a talk on “The Work of Hertz,” focusing on Radio waves. However, to make a good public demonstration, he needed a more dramatic way to demonstrate that the waves travel long distances. For that reason, Lodge decided to use a tube with metal filings in his receiver. Four years earlier, a French Physicist named Eduard Branly had shown that metal filings in these tubes would stick together or cohere when they were in the presence of a radio wave and therefore have a significantly lower resistance (which is why Lodge called it a coherer). Lodge had the bright idea of setting up a separate circuit with an antenna, a battery, a coherer, and a current meter that turned a mirror so that it was visible to all when the current changed. When he created a radio wave on one side of the room, the metal in the coherer stuck together and became conductive so that the current meter turned! In other words, Lodge made the first known wireless signal that could be easily detected. Lord Rayleigh told Lodge, “There is your life work!” But instead, Lodge went on vacation and then became distracted with other work and mysticism.

Marconi, however, was not distracted. In fact, he was possessed. Once he read of Lodge’s experiment, he spent thousands of hours improving the coherer through trial and error. Marconi created a coherer that was a thin small tube with only a tiny v-shaped area for the metal shavings in a partial vacuum. Marconi also found that a tall antenna worked better than a short one and an antenna that was grounded (stuck in the ground) at the top of a hill worked even better.

Marconi coherer

Marconi cohererThese inventions were important, but Marconi’s biggest input has to do with his complete lack of understanding of basic Physics. See, at the time, no one thought Radio waves could travel that far because they move in a straight line and the Earth is curved. It is like having a really bright light on a lighthouse: after a certain distance, you can’t see it no matter how bright it is. Marconi didn’t have a good answer for this, he was just really, really convinced that it would work out – somehow. Still, he needed a way to make a very powerful radio wave. And, luckily for him, Nikola Tesla had already figured that out.

Back in the summer of 1889, Nikola Tesla had heard about “the miracle” of Hertz’s waves at the World’s Fair in Paris. Inspired, he adjusted the transmitter by using an AC source instead of a DC battery and an interrupter and moving the position of the capacitor (or condenser) and making it variable. This “oscillating transformer” made an extremely high voltage alternating current and Tesla patented it in April of 1891. What he invented was quickly called a “Tesla coil” and it was a sensation. Tesla wasn’t interested in long-distance telegraphs, he had loftier ideals: long-distance wireless lighting, and then electrifying the atmosphere, and even making the whole Earth “quiver” with electricity. All of this, by the way, is total nonsense, but they had no way of knowing that at the time. In fact, in March of 1901, J.P. Morgan gave Tesla $150,000 for a giant whole-Earth transmission tower!

Meanwhile, Marconi was busy trying to build his transmitter and receiving towers. To make a powerful radio wave he outright stole some of Tesla’s patents. At first, Marconi’s patent was rejected by the patent office as being too similar to Tesla’s previous ones. Undeterred, Marconi left the details to the lawyers and built giant radio receivers & transmitters in Cape Cod and in Cornwall, England. The machine in cape cod was so loud that it was affectionately known as “the thunder factory.”

On December 12, 1901, Marconi said that he heard an SOS in Cape Cod from England over 2,200 miles away. I used the phrase “said that he heard” because there was much doubt at the time whether he actually did hear the signal and now we are completely convinced that he did not (radio waves at that frequency don’t go that far in the day). Because of the skeptics, two months later Marconi listened to signals from Cornwall on a ship as it sailed away (with people to verify it) and got a message as far as 2,000 miles away but only at night. During the day he could only get signals at 700 miles. Marconi called this “the daylight effect.” His daughter wrote that he yelled, “Damn the sun! How long will it torture us?” Marconi had the odd theory that the wave skimmed along the surface of the Earth due to the fact that he grounded his antennae and the sunlight somehow acted like a fog, and Tesla thought the signal was going through the earth just as he had predicted with no reason for it not to work during the day. Later that year Oliver Heaviside (the man who condensed Maxwell’s equations from 20 to 4) solved this riddle. He thought that a part of the atmosphere reflects the radio wave so that it could bounce along the surface and the ground. He also thought that this layer had more complexity during the day so that the waves would often bend instead of bounce. Therefore, during the day, it was harder to get the wave to travel long distances, as it would often just leave the Earth as scientists had originally predicted.

Irrespective of why Marconi had proven that Radio signals would travel much farther than they should have if they traveled in straight lines. Marconi was proud to proclaim, “There is no longer any question about the ability of wireless telegraphy to transmit messages across the Atlantic.”

When Tesla heard about Marconi’s accomplishments he was unconcerned saying, “Marconi is a good fellow. Let him continue. He is using seventeen of my patents.” However, that good feeling was destroyed in 1904 when the patent office reversed their rulings and gave the patents to Marconi! At the same time, J. P. Morgan was getting pretty frustrated with Tesla and the “money pit” of a tower. Marconi’s method was cheaper and was proven to work. Morgan stopped funding Tesla, and Tesla had to give up the project and had a nervous breakdown he died penniless 39 years later. A few months after Tesla’s death, the US Supreme Court recognized Tesla and Lodge (and others) for their initial contributions to wireless telegraphs.

Back to Marconi. Despite the fact that Marconi didn’t know how or why his system worked, he did manage to get them to work. Soon, many ships had “Marconi machines” to send “Marconigrams”. In a feat of pure propaganda, Marconi even managed to co-win a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1909! Marconi moved back to Italy, joined the Italian fascist party, and became close friends with Mussolini. On July 19, 1937, Marconi had a heart attack and politely told his valet, “I am very sorry, but I am going to put you and my friends to considerable trouble. I fear my end is near. Will you please inform my wife?” Marconi died forty-five minutes later. Two days later, at Marconi’s funeral, wireless and radio operators around the world held two minutes of silence in his honor. That was the last two minutes when there were no human-made radio signals invisibly whizzing through the air.

Of course, in 1937, a large portion of radio signals was not sending Morse code, instead, they were broadcasting music and news. How did we change from wireless morse code to music? I’ll explain the Physics of the first radio broadcast next time on the secret history of electricity!

The post Who invented the Wireless Telegraph? appeared first on Kathy Loves Physics.

How a Real Life Dr. Frankenstein Inspired Mary Shelly & Birthed Electrobiology

Was there a real Dr. Frankenstein? Yes, there was, his name was Giovanni Aldini and he actually managed to make corpses move with electricity! However, the gruesome nature of his experiments obscured the fact that he was an amazing scientist who revolutionized biology and medicine all in the name of familial love! Ready for both a ghoulish and an inspirational story?

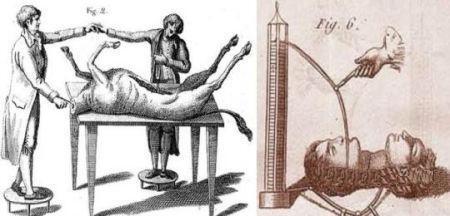

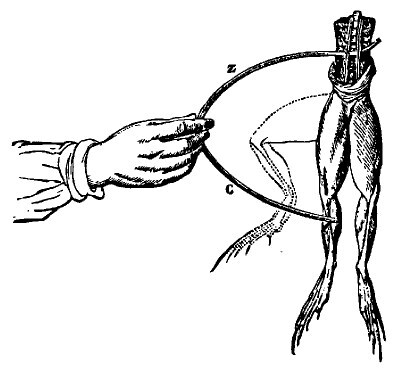

On January 18th, 1803, a man named George Forster was put to death for drowning his estranged wife and one of their children. At the time, dissection and other manipulations of a corpse were considered sacrilege so, as further punishment, after Forster had been hung for his crimes, his lifeless body was taken to a public operating theatre where an Italian Physicist named Giovanni Aldini experimented with the corpse. Aldini was a “Galvanist” or a person who believed that “animal electricity” is what makes animals alive and that certain procedures could release this electricity even when the animal (or person) died! Aldini proceeded to use a battery to get the dead man’s jaw to shake and even open his left eye. The highlight (so to speak) was when Aldini stuck one electrified probe in the corpse’s ear and another one in his rectum, which made Forster’s legs kick and his right-hand clench and pump in the air! The warden of Newgate prison recorded that several people who saw this experiment thought that Foster was, “on the eve of being restored to life.” He also claimed that these demonstrations were so dramatic and disturbing that they caused a church usher to die of fright!

Giovanni Aldini

Giovanni AldiniWhy was Aldini was probing a corpse in the first place? It had to do with his family. Aldini’s uncle was a doctor and anatomy professor named Luigi Galvani who was assisted in his work by his wife Lucia. When Aldini was in college, his aunt and uncle accidentally discovered that if a decapitated, skinned frog was touched with an electrified probe it would “jump” like it was alive. Aldini was fascinated and as soon as he graduated he joined them and helped them electrocute every animal in sight! They discovered that all animals would respond physically to electricity, although frog legs seemed to have the most dramatic effect. They also noticed that the convulsions were most pronounced when the electrical probes were connected to an animal’s nerves or muscles. They weren’t the first to notice that electricity makes animals jump, but they were the first to theorize that electricity is how muscles and nerves normally function.

While playing with dead frogs they also found that putting both copper and iron into a frog’s body produces electricity with no static electricity or thunderstorms in sight! Crazy huh? In the middle of all of this exciting research, Lucia Galvani fell very ill and, despite Luigi’s devoted care, she died from complications from her asthma in 1788. As a result, Luigi Galvani did not publish his work until 1791. In this paper, Galvani postulated that all animals have what he called “animal electricity” inside them which is what makes them (and us) alive. Galvani had made the spark of life literal.

Imagine Galvani and Aldini’s dismay when the very next year, Alessandro Volta, Europe’s premier electrical scientist, published a paper that claimed that “animal electricity” was bunk! Volta had found that two different metals will work to electrify a live frog and he decided that the electricity came from the dissimilar metals, not the frog itself.

Galvani didn’t want to respond. He was a quiet, soft-spoken religious man who did not like conflict and he was also still morning his wife’s passing. Aldini, however, was rearing for a fight, especially after Galvani had just nursed him through an illness. This is how Aldini described what happened in 1794:

“[My Uncle Galvani] was treating me for a deadly fever. After having escaped, thanks to his generous care and efforts, a nearly unavoidable death, I started to work zealously to bring support to a doctrine that I trusted, despite the attacks under which it came. I felt at ease to be able to pay a tribute to the truth and, at the same time, to provide Galvani with a public account of my gratitude.”

Aldini began writing and traveling throughout Europe electrocuting animals (and people) and promoting his uncle’s theories. From this time on, Aldini was the face of Galvanism.

It became a big debate between the Voltists (lead by Volta) and the Galvanists (lead by Aldini). Was the frog jumping because it possessed an electrical life force or was the frog jumping because two different metals created electricity? By the way, both sides’ ideas were partially correct and partially incorrect. The Galvanists were correct in that all living things use and produce electricity to make their muscles move and their nerves transmit signals, so if you artificially add electricity even a dead animal will react. However, they were wrong in thinking that a dead creature would create its own electricity. Volta was correct that the two different metals were creating electricity in this experiment. However, Volta missed was that he was actually studying a chemical reaction: it needed a chemical (an acid or a base) to interact with the metals in order to create electricity.

In 1800, Volta struck another blow to the Galvanist cause. He had created a device out of metals that would produce a shock without the different metals touching anything alive or formally alive. Volta had taken discs of silver and zinc and piled them up with cardboard soaked in saltwater between them. If you touched either end with wet hands you could get a shock out of this pile in a continuous current. In fact, Volta had invented the battery! Volta wrote that his research was motivated because he, “found myself obliged to combat the pretended animal electricity of Galvani.”

Although Volta’s battery seemed at first to invalidate Galvani’s theories, in an ironic twist, the battery turned out to be an invaluable tool for the study of electricity in organic systems.

Aldini began to use Volta’s battery with astonishing results. By electrocuting the brain of a decapitated ox, he made the ox’s facial muscles move! In 1802, Aldini started to experiment on the corpses of various criminals and, like with the ox, managed to manipulate their facial expressions by electrifying parts of their brains! This was the first real glimpse of how the brain works, and even with his crude apparatus Aldini was the first person to realize that one side of the hemisphere of the brain controls the opposite side of the body.

Aldini also created electric shock therapy! First, Aldini conducted a “long series of painful and disagreeable experiments” on his own head with Volta’s battery to try to get a gauge of how powerful and useful electric jolts could be. He then gave shocks to a 27-year-old farmer named Louis Lanzarini who was suffering from debilitating depression and was being held in an insane asylum. According to Aldini, Lanzarini immediately began feeling better and smiling and after several days of shocks, Lanzarini was considered cured and was released from the asylum! Although electroshock therapy was abused and misused in the 1950s and 60s, it is actually still considered one of the most effective treatments for severe depression that exists today. Sometimes doctors even electrically stimulate the brain directly (called deep brain stimulations) in a manner that Aldini would have found fascinating.

In addition, Aldini correctly predicted that electric shocks could be used to force a damaged heart to beat (although he was never successful with his primitive batteries). In this way, Aldini is the father of the defibrillator and the pacemaker.

Finally, Aldini’s gruesome experiments grabbed the public’s attention to the extent that “Galvanism” became synonymous with “using electricity to reanimate a corpse”. This popularity is how, thirteen years after Aldini electrified Foster’s dead body, an 18-year-old woman named Mary had heard of galvanism. Then when Mary and her friends were trying to entertain each other by writing scary stories during a cold vacation they had a discussion about galvanism and reanimating corpses. Mary Shelley said that it was this discussion that inspired her to write a horror story called “Frankenstein”.

However, unlike Dr. Frankenstein in Mary’s famous story, Dr. Aldini was never trying to re-animate anyone. He merely wanted to “obtain a practice knowledge of how far Galvanism might be employed to revive persons.” If you think of the pacemaker and the defibrillator, Aldini’s ghoulish demonstrations did end up saving many people’s lives, not to mention inspiring the first, and one of the best, science fiction ghost stories of all time.

The post How a Real Life Dr. Frankenstein Inspired Mary Shelly & Birthed Electrobiology appeared first on Kathy Loves Physics.

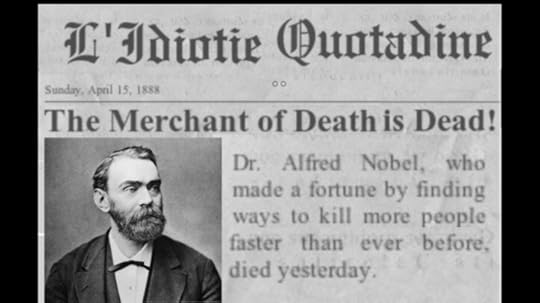

Alfred Nobel’s Obituary Calling Him a “Merchant of Death” Never Happened & Never Inspired the Nobel Prize

If you read many biographies of Alfred Nobel or of the Nobel Prize, including Wikipedia and Encyclopedia Britannica, you will read a dramatic story: in April of 1888 Alfred Nobel’s brother died and a newspaper mistakenly reported that Alfred had died. More than that, the paper ripped Albert to shreds. “The Merchant of Death is Dead!” the newspaper cried, “Dr. Alfred Nobel, who became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday.[1]” Albert Nobel was so distraught by this that he willed most of his vast fortune to create the Nobel Prizes to improve his image. However, some modern biographers have started to wonder if this story is apocryphal, as no one can seem to find a copy of this important newspaper. However, no one has found proof one way or another, until now. I have found pretty conclusive evidence that Alfred Nobel did read his own premature obituary but it didn’t call him a “Merchant of Death” nor did it inspire him to create the Nobel Prizes. In fact, I found that the “Merchant of Death” version of events was basically completely made up by an unscrupulous biographer in 1959.

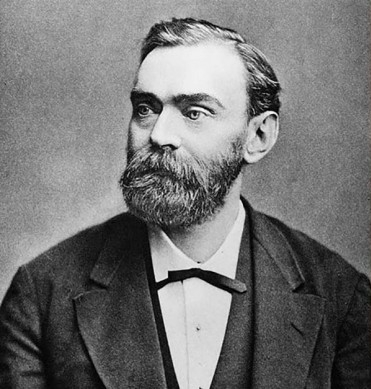

Alfred Nobel

Alfred NobelLet us start with the actual premature obituary. Alfred Nobel’s brother Ludwig did die in Cannes, France in April of 1888, and a newspaper did mistakenly think that Alfred died instead. However, the newspaper printed a far more mild misstatement. The real newspaper blurb stated in full: “A man who can not very easily pass for a benefactor of humanity died yesterday in Cannes. It is Mr. Nobel, inventor of dynamite. Mr. Nobel is Swedish[2].” The next day the paper printed a correction that it was Alfred’s brother who had died not Alfred[3]. His friend Madame Juliette Adam-Lambert then wrote a letter to Nobel saying how glad she was that the rumor was false[4]. It would obviously be traumatic for anyone let alone the private and shy Alfred to tell friends and relatives that he wasn’t dead yet. However, the negativity of this mild statement seems unlikely to have devastated Nobel especially as Alfred Nobel had been known for decades as “the dynamite King[5]” who often had a contentious relationship with the French press[6]. In addition, Alfred was an atheist who had complained just the previous year, “Who has time to read biographies, and who can be so naïve or fatuous as to take an interest in them?[7]” Now it is possible that another French paper made the same mistake and that paper called Nobel a “Merchant of Death” and this disturbed him so much that he created the Nobel Prize seven years later. However, that event seems quite unlikely as we have many of Nobel’s letters to his family, friends, employees, and even his mistress, and nowhere does he mention the whole “Merchant of Death” thing. Mind you, Alfred Nobel was often depressed and he expressed his fears and frustrations freely with his friends and family. For example, he wrote his mistress Sophie Hess in November of 1889, “What a sad end I am going toward, with only an old servant who asks himself the whole time if he will inherit anything from me.[8]” Although Alfred Nobel suffered from melancholy, it was not related to his work, for Albert Nobel stated many times that he felt that dynamite and other weapons would make the world a safer place. See, Nobel thought that if he could make a truly terrible weapon it would scare countries away from war. Back in 1877, eleven years before his brother’s death he told his friend, Bertha von Suttner, “I wish I could produce a substance or a machine of such frightful efficacy for wholesale devastation that wars should thereby become altogether impossible.[9]” He continued to express that sentiment repeatedly for the remainder of his life. To Alfred Nobel, weapons and dynamite did not make him a “merchant of death” but a “merchant of peace” and anyone who didn’t agree with him was short sited. In addition, in 1892 (4 years after his brother’s death), Alfred Nobel went to his first Peace Conference[10] and became enamored of the disarmament movement and asked his secretary to look into how he could support it. When his secretary told him to start a propaganda magazine he replied, “I might as well just throw my money out the window! [11]”. If Alfred Nobel were only interested in PR, wouldn’t he have wanted a peace paper in his name independent of how effective it was to create actual change?

So, where did the “merchant of death” story come from and why has it taken hold of our consciousness? As far as I can tell, a man named Nicholas Halasz was the first person to suggest that Nobel created the Nobel Prize because of the premature obituary and the first person to state that the obituary called Alfred Nobel a “Merchant of Death” in his biography of Nobel published in 1959. In fact, Halasz began his book “Nobel: a Biography” with Alfred reading his own obituary and being “overwhelmed” to realize that he was known, “quite simply a merchant of death, and for that alone would he be remembered.[12]” Later in the book the author repeated the story and said that the paper called Nobel, “a merchant of death who had amassed a huge fortune from the sales of more and more devastating weapons.[13]” But where did Halasz get that idea and that provocative phrase? Halasz did not include a single reference in his book so we have to guess his motivations and sources. But the biggest clue may be the term “Merchant of Death”. Startlingly, as far as I can find, no one used the term “Merchant of Death” about anyone for over 43 years after Ludwig Nobel’s death. The term seems to have been coined by an author of an article written in 1932 about a real character named Basil Zaharoff who was known for his ruthlessness, selling munitions to anyone who had enough money. In fact, Zaharoff was even known to encourage conflict and then sell arms to both sides! This article was poetically titled, “Zaharoff, Merchant of Death”[14]. Two years later, another author “borrowed” that phrase for his book on arms dealers, which he titled “Merchants of Death: A Study of the International Armament Industry. [15]” The New York Times reviewed this book[16] and after that, the phrase “Merchant of Death” was often used to describe people who sell weapons[17]. By the late 50s, Halasz must have heard the term “Merchant of Death” for arms dealers but had not investigated and found that the term was only 25 years old and therefore could not have been in Alfred’s premature obituary.

Why did Halasz think that an obituary inspired Albert Nobel? Well, he might have felt that it was totally illogical that an arms dealer and an inventor of dynamite would make a Peace prize. Nobel’s theory that terrible weapons would end war seemed, in the 1950s, to be so naive as to be absurd. So, when Halasz read about Nobel reading his own obituary, probably from Madame Adam-Lambert’s letter of relief that Nobel wasn’t dead, it must have seemed like the key to the puzzle. When Halasz couldn’t find the actual obituary, in an act of journalistic malpractice he just made one up. After Halasz’s book was published the phrase “Merchant of Death” was too delicious to not repeat. In addition, the story of a premature obituary inspiring the world’s most important prizes was a simple and satisfying origin story. Soon, many biographers were repeating this version of events. In 1991, a Swedish actor and historian named Kenne Fant wrote a biography of Alfred Nobel that is considered the gold standard that said, “the obituary characterized Alfred as a “merchant of death” who had built a fortune by discovering new ways to “mutilate and kill.” Alfred … became so obsessed with the posthumous reputation that he rewrote his last will, bequeathing most of his fortune to a cause upon which no future obituary writer would be able to cast aspersions.”[18] Kant’s book also doesn’t have references, so it is not clear if he got the story from Halasz or from someone who was influenced by Halasz. Although the “Merchant of Death” premature obituary origin story is satisfying, it just isn’t true.

[1] www.wikipedia.com/Alfred_Nobel

[2] Le Figaro April 15, 1888 p. 1 & 2 Link: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k280366k/f1.item (I found the link due to the fantastic research of Lars Bosteen who posted an answer on stackexchange.com: https://history.stackexchange.com/que...)

[3] Le Figaro April 16, 1888 p. 1 Link:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k280367z.item

[4] Adam-Lambert, J to Nobel, A April 1888 translated in Larsson, Ulf Alfred Nobel: Networks of Innovation (Nobel Museum, 2008) p. 193

[5] According to Fant, K Alfred Nobel: A Biography (1991) p. 97

[6] According to Nobel, Alfred. “Alfred Nobel’s House in Paris”. Nobel Media AB. Nobel Media AB, Alfred Nobel was charged with “high treason against France” in 1891 for selling Ballistite to Italy so he escaped from France to Italy.

[7] Nobel, A to Nobel, L 1887 in Fant, K Alfred Nobel: A Biography (1991) p. 1

[8] Nobel, A to Hess, S, Nov 11, 1889, translated in Fant, K Alfred Nobel: A Biography (1991) p. 318

[9] Nobel, A recalled by Suttner, B in Memoirs of Bertha Von Suttner, The Records of an Eventful Life (1910) p. 208

[10] According to Suttner, B in Memoirs of Bertha Von Suttner, The Records of an Eventful Life (1910) p. 429

[11] Nobel, A quoted in Sohlman, R The Life of Alfred Nobel (1929) p. 205

[12] Halasz, N Nobel: A Biography (1959) p. 7

[13] Halasz, N Nobel: A Biography (1959) p. 140

[14] Hauteclocque, X “Zaharoff, Merchant of Death” The Living Age Vol. 342 (1932) p. 204

[15] Engelbrecht, H. C. The Merchants of Death (1934)

[16] “Merchants of Death Who Profit When Men Go to War: Three Excellent Books on the World’s Armament Industry That Are Written With Fine Humanitarianism” The New York Times Book Review, April 29, 1934 p. 3

[17] According to dictionary.com and wikipedia.com “Merchant of Death” originated with the book “Merchants of Death” published in 1934, but of course, that author got the term from the article about Zaharoff that the authors referenced in their book.

[18] Fant, K Alfred Nobel: A Biography (1991) p. 207

The post Alfred Nobel’s Obituary Calling Him a “Merchant of Death” Never Happened & Never Inspired the Nobel Prize appeared first on Kathy Loves Physics.

March 11, 2022

Charles Proteus Steinmetz: History and Science

Both during his life and after his death, Charles Proteus Steinmetz was often referred to as the “Wizard of Schenectady.” However, when I looked into his life, most of his famous contributions occurred when he arrived in America, penniless, with no English or practical engineering skills in June of 1889 (he was a political refugee from Germany due to his socialist beliefs), and when he was transferred to Schenectady in February of 1894.

Nevertheless, I believe that his moniker of “Wiza...

February 18, 2022

Charles Proteus Steinmetz Biography

A couple of years ago, a supporter of this channel with the amusingly terrifying name of Jack D. Ripper suggested I should look into the history of Charles Proteus Steinmetz, especially in regards to the story of him with Henry Ford.

Intrigued, I looked into him and I was hooked. Steinmetz is fascinating to me. His science and engineering contributions were immense: his theory of hysteresis, creating phasors, popularizing 3-phase in the US, high voltage AC studies, and creating...

January 19, 2022

How Tesla And Ferraris Invented The Two-Phase Motor

As I said in my video on the history of 3-phase electricity, both Nikola Tesla and Galileo Ferraris discovered two-phase electricity and the two-phase motor that were, according to Tesla, “identical almost to the smallest detail.” 1 So, how did these two men develop this fantastic discovery?

Table of ContentsIntroductionHow Ferraris Got InvolvedFerraris’ InfluenceHow Arago’s Wheel might have inspired TeslaHow Two-phase was developedReferencesVideo Scr...December 27, 2021

History Of 3-Phase Electricity And It’s Distribution

Almost all of our electrical systems use 3 phase AC electricity, but how does it work, why was it invented, and who invented it? Ready for the surprising but complex and story as well as the answer to why some countries use 50 Hz and some use 60 Hz and one country uses both?

Table of ContentsIntroductionShort History of 2-phaseWestinghouse and ShallenbergerGalileo FerrarisNikola TeslaMichael Dolivo-DobrovolskiInitial interest in 3-phaseDevelopmen...December 3, 2021

The Origin of The Polyphase Current

As I said in my video on the history of 3-phase electricity, both Nikola Tesla and Galileo Ferraris simultaneously discovered 2-phase electricity and the 2-phase motor that were, according to Tesla, “identical almost to the smallest detail.”[1] So, how did these two men come up with this amazing discovery? That is what this supplemental video is all about.

Table Of ContentsGalileo Ferraris: A Quick BiographyThe First Brushless Polyphase GeneratorTesla’s MotorArag...November 9, 2021

James Joules: The Beer Brewer Who Changed The World

Most of us who know of James Joule know of him because we have heard of Joule’s law, his paddle experiment and/or we know that energy is measured in Joules in his honor. But who was Joule and how and why did he make his discoveries and what does it have to do with his friendship with a young scientist named William Thomson later knighted Lord Kelvin?

The Brewer Who Changed The WorldTable of ContentsWho is James Joule?Joule’s ChildhoodJoule and SturgeonJoule and C...