Katherine Frances's Blog, page 101

December 12, 2017

littlestpersimmon:smitten ✨

December 11, 2017

k-frances:

For part one in which I define character arch and explain it’s importance, click...

For part one in which I define character arch and explain it’s importance, click here.

Using Cognitive Dissonance to Define Character ArchWhat the H is Cognitive Dissonance

This is, simply put, the feeling all humans get when they are conflicted about themselves. The process starts like this: “I am x. X’s cannot be Y’s, but I am also Y…wtf am I?” People do not like feeling cognitive dissonance. It’s uncomfortable, and therefore it’s [basically proven] human nature to avoid or correct cognitive dissonance whenever possible. Let me give a quick example we can all relate to.

I like to write and consider myself a writer. I never write.

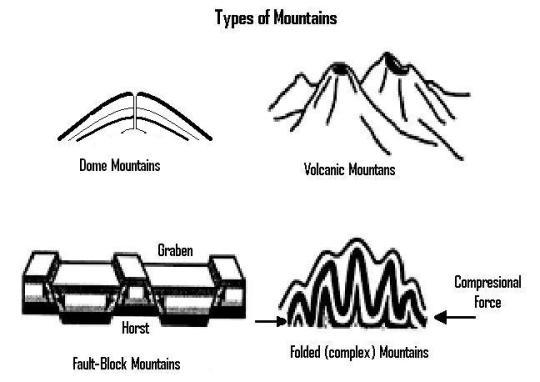

Those two thoughts about myself can exist at the same time, but I don’t like it. I have a psychological need to git rid of one of them. The graph bellow demonstrates the choice I am now forced to make in order to alleviate this uncomfortable feeling of dissonance.

[I did not make this]

Using the previous example, my belief is that I am a writer. My action is that I don’t ever write. My dissonance goes up. I have three choices.

A] I can change my belief about myself and accept that I am not a writer and I must not like writing because I never do it.

B] I can change the action, and write.

C] Or, I can change my perception of my action so it no longer upsets me, i.e. “I write when I have time and whenever I can even though that’s not very often.”

Any of these three bring down my dissonance.

How the H can I use this in my writing?If you have a well developed character, you should be able to fill out the first two squares. Now, the part that says ‘action’ doesn’t really have to be an action. It can be another belief, but most of the time it will be an action or a situation. “I am a writer. I had a stroke and now suddenly don’t know how to physically write.” for example. The point is, within the scope of your story, you should be able to identify two conflicting situations your hero is in. The change that occurs within them [that forms the arch] can be any of the three green options.

Example

Hero believes he is a normal dope. But he’s called to action and has no choice because he is chosen, and it turns out he is quite special [conflicting action/belief/situation] Hero wonders, who the hell am I?

A) I guess I’m not a normal dope after all. Consider my belief of myself changed.

B) Whoa, whoa, whoa. I’m going back home to be a dope, this adventure is not for me. Goodbye conflicting action/belief/situation, I’m not special

C) I am a normal dope at heart. Just because I have all these awesome powers doesn’t change that perception of myself.

So, this is a very simplistic story structure that I used as an example, and a very classic archetype. But this same principle can be applied to any character. This really helps when you find your character is faced with challenges in your plot driven story, but you don’t really know how they are changing to overcome these obstacles. Often in plot driven stories, the character’s change is necessary change [in order to defeat the big bad] and you as the writer might be creating this change without even realizing you’re doing it. Recognizing the ways your characters are changing is important because, by bringing out the most important and dropping more clues and drawing more attention to them for the reader, you can fully carve out your character arch within an otherwise plot driven story.

k-frances:

For part one in which I define character arch and explain itâs importance, click...

For part one in which I define character arch and explain itâs importance, click here.

Using Cognitive Dissonance to Define Character ArchWhat the H is Cognitive Dissonance

This is, simply put, the feeling all humans get when they are conflicted about themselves. The process starts like this: âI am x. Xâs cannot be Yâs, but I am also Yâ¦wtf am I?â People do not like feeling cognitive dissonance. Itâs uncomfortable, and therefore itâs [basically proven] human nature to avoid or correct cognitive dissonance whenever possible. Let me give a quick example we can all relate to.

I like to write and consider myself a writer. I never write. Â

Those two thoughts about myself can exist at the same time, but I donât like it. I have a psychological need to git rid of one of them. The graph bellow demonstrates the choice I am now forced to make in order to alleviate this uncomfortable feeling of dissonance.Â

[I did not make this]

Using the previous example, my belief is that I am a writer. My action is that I donât ever write. My dissonance goes up. I have three choices.Â

A] I can change my belief about myself and accept that I am not a writer and I must not like writing because I never do it.Â

B] I can change the action, and write.Â

C] Or, I can change my perception of my action so it no longer upsets me, i.e. âI write when I have time and whenever I can even though thatâs not very often.âÂ

Any of these three bring down my dissonance.Â

How the H can I use this in my writing?If you have a well developed character, you should be able to fill out the first two squares. Now, the part that says âactionâ doesnât really have to be an action. It can be another belief, but most of the time it will be an action or a situation. âI am a writer. I had a stroke and now suddenly donât know how to physically write.â for example. The point is, within the scope of your story, you should be able to identify two conflicting situations your hero is in. The change that occurs within them [that forms the arch] can be any of the three green options.

Example

Hero believes he is a normal dope. But heâs called to action and has no choice because he is chosen, and it turns out he is quite special [conflicting action/belief/situation] Hero wonders, who the hell am I?Â

A) I guess Iâm not a normal dope after all. Consider my belief of myself changed.

B) Whoa, whoa, whoa. Iâm going back home to be a dope, this adventure is not for me. Goodbye conflicting action/belief/situation, Iâm not special

C) I am a normal dope at heart. Just because I have all these awesome powers doesnât change that perception of myself.Â

So, this is a very simplistic story structure that I used as an example, and a very classic archetype. But this same principle can be applied to any character. This really helps when you find your character is faced with challenges in your plot driven story, but you donât really know how they are changing to overcome these obstacles. Often in plot driven stories, the characterâs change is necessary change [in order to defeat the big bad] and you as the writer might be creating this change without even realizing youâre doing it. Recognizing the ways your characters are changing is important because, by bringing out the most important and dropping more clues and drawing more attention to them for the reader, you can fully carve out your character arch within an otherwise plot driven story.

k-frances:–Visceral Definitions by K-frances

k-frances:âVisceral Definitions by K-frances

Kim Shimmers and the Veil of Death

A Harry Potter fanfic by me (and the 4th instalment in the Kim Shimmers series)

How could we ever hope to flicker on against a

darkness so complete, against an evil so prevailing?

This Harry Potter fan fiction  (as long as all goes according to plan) will be posted at the beginning of every week. The pictures above are not mine, though I edited some.

Chapter 2

The Ring, the Sword, and the Snake

Fred did visit Kim a few times over the course of the next week and a half, occasionally bringing his brother along with him. She and her mother would watch the twins play one-on-one quidditch games in her back yard, much to her motherâs delight. The twins seemed to enjoy it too, since they didnât have a yard anymore now that they lived in the city.

One Saturday morning Aunt Brit decided to visit, saying itâd been too long since sheâd seen her favorite niece.

âSo Kim, howâs Hogwarts? And London?â she asked as she and Kimâs mother sat around the kitchen table, a kettle brewing on the stove.

âBoth are good.â

âI heard about what happened last yearâ¦â

Kim got a bit stiff as her motherâs attention perked up.

âWhat happened?â Mrs. Shimmers asked.

âIt was just a scandal with one of the teachers,â Kim answered quickly.

âMore than just a little scandal,â Aunt Brit said, standing to poor herself a cup of tea from the pipping kettle. âThe woman was terrorizing the students all because the Ministry was so cock-sure He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named hadnât returned.â

âHe-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named?â her mother asked.

Brit looked over her shoulder at her, a bit surprised, and then turned a skeptical gaze on Kim. âYou really havenât told her a thing, have you?â

Kim stammered for far too long.

âWhat havenât you told me, Kim?â Mrs. Shimmers pressed sternly.

âWell-â Kim continued to stammer. âI-itâs got to do with the magical community in the UK⦠I donât know, I guess I didnât think youâd be interestedââ

âDidnât think sheâd be interested?â Brit said incredulously.

Kim grimaced at her resentfully. âFine. I didnât want you to worry, Mom. Itâs nothing I canât handle.â

âWell, you certainly wonât be handling it,â Brit said, as if the idea were a relief. âThe ministry and the aurorsâll have to take care of it, and Iâm sure they will. Luckily youâve got no part in it.â

Kim just stared between her mother and her Aunt. If only you knew how wrong you are. But she was immediately glad that they didnât know.

Just then there was a wrap on the door. Mrs. Shimmers stood, looking vaguely surprised they had more visitors.

âWhoâs that?â Brit asked as she leaned to try and see through the kitchen doorway to the window of the side door to the house.

âProbably someone lost,â Mrs. Shimmers said, disappearing onto the porch to answer the door.

âYou really should keep your mom a bit more informed,â Aunt Brit said. âI understand not wanting to explain everything. Itâs a lot to try and explain to a muggle. But she should at least know the basics.â

âYeah, I guess⦠I just donât have a lot of time to talk to her, and it never really seems to come up. But Iâll tell her more from now on, I will,â she added hastily in response to the raised-brow look she was getting from her aunt.

âUh, youâve got company, Kim,â her mother said as she reentered the kitchen. Kim looked up to see she was followed by a tall, very old wizard with long grey-purple robes that whisked along the floor. He had a long silvery beard and wore half-moon spectacles.

âYouâre not- the Dumbledore,â Aunt Brit said in a bit of a gasp, standing to shake his hand.

âYou know each other?â Mrs. Shimmers asked, not understanding.

âOh, no,â Brit laughed with a little embarrassment.

âHeâs kind of famous,â Kim explained to her mother.

âWell, what next for today?â Mrs. Shimmers chuckled as she sat in her seat. âFirst I find out about secret scandals I should already know, and now there are famous wizards showing up at my door.â

âMom,â Kim groaned under her breath as she approached Dumbledore who was smiling as if cheerfully amused by all this. âThis is the Headmaster.â

âOh. Well, nice to meet you. You work at Kimâs school?â she said, painfully at ease with him. Kim supposed her mother was a bit unaware of that cultural element in the wizarding community; headmasters were not like principals.

In young-adult novels, queer love stories have begun to feel mainstream

âAnna-Marie McLemore, author of the new âWild Beauty,â agrees that fantasy YA has allowed for more inclusion, for readers to see themselves on the page. âIt was incredibly freeing to me, to realize I was writing queer and trans characters in worlds that have magic â it was like, I can write about identity, but also about magic and let LGBTQ into that world. I was so excited to write about these queer Latina girls in ballgowns in gardens, and we belong there, even if we didnât see ourselves there growing up.ââ