Trudy J. Morgan-Cole's Blog, page 46

February 19, 2019

Toxic Femininity

Photo: Lukasz Dziegel, pexels.com

Throw into the 2018 file of “Things That Happen So Regularly We Hardly Even Notice”: liberal friend uses the phrase “toxic masculinity” on social media to refer to a man abusing his partner or shooting a bunch of strangers or whatever. Conservative friend responds aghast to the idea that “masculinity is toxic” and rushes to the defense of all the great, truly MANLY men she knows who embody masculine qualities. Tired liberal friend explains that the phrase “toxic masculinity” does not mean “being masculine is toxic.” Blah blah blah: at this point we all know our lines.

But my latest go-round on the Merry-Go-Round-of-Gender-Norm-Debates triggered a new thought: Is there such a thing as “toxic femininity”?

If “toxic masculinity” means not “masculine behavior is inherently toxic” but “there is a version of masculine behavior that can be expressed in toxic and damaging ways” — violence, anger, abuse, rape, etc — is there a female corollary? Are there behaviors our society marks as typically “feminine” that can also be harmful, both to the woman in question and to those around her?

If your answer to this is “no,” I can only assume you have never gone to a girls’ school, lived in a girls’ dorm, belonged to a church women’s group, or worked in a largely-female workplace.

Toxic femininity? Let me try a few words out on you.

Catty.

Manipulative.

Gossipy.

Competitive.

Backstabbing.

Bitchy (and not in the good, empowering, “I’m a bad bitch and I own it!” kinda way, but in the “Susan, that cake you brought to the shower was delicious — I never would have guessed you bought it at Costco” kind of way).

Amid all the talk of female empowerment and feminist sisterhood, we also have all these images in our head. The catty coworker with the snide remarks. The judgey girls’ clique in junior high. The church lady who looks down her nose at anyone who doesn’t dress right. The girl who’s your best friend right up until she steals your man. The woman who gets what she wants from the male boss by using her “feminine wiles” to undercut another female employee. The list goes on and on.

Yes, there’s such a thing as toxic femininity. Having lived in the world as a woman for 53 years, I’ve been on the receiving end of other women’s stereotypically feminine bad behavior, and yes, I’ve perpetrated some of it myself.

The thing is, toxic femininity has the exact same root cause as toxic masculinity:

Patriarchy.

Don’t misunderstand me here. I’m NOT saying individual women are not responsible for their own bad behavior, or that women’s bad behavior is men’s fault. I’m talking about a societal system that’s bigger than any individual man or woman: a set of expectations about male and female behavior that’s baked into our culture and into the way we raise and socialize little boys and little girls, just as surely as Susan’s cake was baked at Costco.

The same patriarchal system that tells men that they have to be physically strong and tough to be “manly,” that tells them violence is more acceptable than expressing emotions, also delivers some powerful messages to women:

Your most important value is your physical appearance

Your most important achievement is attracting a man’s attention

Other women are your competition for male attention

Exercising power directly — especially over men — is inappropriate: you must learn to be the “power behind the throne”

Teach generations of women these things, directly and indirectly, for centuries, and what do you get? Competition among women. Women using manipulative, underhanded tactics to control men and other women. Gossip. Back-stabbing. In a word, bitchiness.

Sure, part of the cure is for individual women to resist those messages and behave better (and teach our daughters and other young women to do so). Just as the cure for toxic masculinity is, in part, individual men resisting violence and aggression and teaching others to do so.

But a systemic problem can’t be entirely solved by individual solutions. The problem of toxic femininity comes down to the same thing as toxic masculinity: the patriarchy is bad for everyone.

And that’s why it needs to be dismantled.

February 14, 2019

On the Death of Robots: Who Gets to be Human?

[image error]I’ll admit it: like lots of people, I’ve shed a tear or two over the “death” of the Opportunity Rover, which spent far longer recording information on the surface of Mars than it was ever supposed to. After seeing dozens of cartoons and tributes, it’s hard not to anthropomorphize a machine that embodied so much of our humanness, our striving to know more about the universe we live in.

The story of Opportunity and the response to its “death” showcases the best of humanity: our curiosity, our ingenuity and ability to create technology that satisfies that hunger for knowledge, and our empathy, which is so vast that we can anthropomorphize a data-collecting robot, endow it with human characteristics, and mourn its loss as if it were one of us.

As a species, we take my breath away. We are amazing.

At the same time, the machines of human ingenuity churn away here on earth – answering questions, solving problems, and at the same time destroying the very planet we live on, the air we breathe and the water we drink. The creativity that sent Sojourner, Opportunity, Spirit and now Curiosity to Mars has not, so far, been channelled towards making our own planet a fit place for our great-grandchildren to inhabit.

Nor has our incredibly capacity for empathy and imagination enabled us to humanize the creatures who are being endangered and made extinct by our rapacious greed – or even our fellow humans who suffer from floods, desertification, wildfires. We weep for a dead robot and ignore dead animals, dead fish, dead human children.

As a species, we take my breath away. We are horrible.

We can look at robots, at animals, at fictional characters in books, and make them human by the power of our imagination – care about their fates as much as those of our fellow human beings. But our empathy has limits.

We anthropomorphize dogs and cats, celebrate them as our best friends and make them the heroes of books and movies. But an insect in the Amazon rainforest that a whole ecosystem depends on? We can’t imagine it as human, so we ignore its extinction.

Those who work in conservation are familiar with this paradox. Here in Newfoundland, we were subjected for decades to cries of pity for big-eyed harp seal pups, which were never endangered, but which looked so cute they were easy to humanize. The far less adorable northern cod, which really was endangered, didn’t make a good conservation poster, so trawlers dragged the ocean floor and depleted its stocks to the point that they will probably never fully recover.

We can’t even imagine all our fellow human beings as human. The Other: the foreigner, the refugee, the illegal immigrant child in a detention centre, the homeless panhandler on the corner. If we really saw them as human – even as human as our dogs or our Mars rovers – could we ignore their suffering as we do?

(This lack of imagination is not limited to one side of the political spectrum. Even as I write this, I’m reminded that my pro-life friends would be quick to point out that I, as a pro-choice progressive Christian, might not be capable of imagining a human fetus as fully human, either, until it passes a certain arbitrary cut-off point. We see each other’s failures of empathy more clearly than our own).

We cannot yet travel to Mars, but we can send our emissaries there to do our work, and invest in them our imagination, our hopes, even our empathy. They represent us, and so we imagine that they are us, in some small way.

Yet we will never solve the problems of this planet – the problems of a changing climate, of poverty, of terrorism and violence and inhumanity – till we broaden our vision of who – and what! – deserves our empathy. Until everyone gets to be seen as human.

I honestly don’t know if we will. But a species that can send Opportunity to Mars and fall in love with it – that species certainly can do all that and more.

February 8, 2019

Another Take on Bookshelves

[image error]

The photo above shows a few of my (many) most-loved books from the last year, which was a very good reading year for me. I’ve already blogged about my Top Ten book list and a few of the stats that analyzed my reading habits for the year, but I wanted to draw a sharper focus on a few of these books for one particular reason: I wouldn’t have found these books if I hadn’t gone looking for them.

Let me explain.

I’ve been an avid reader since I could read. I’ve been tracking my reading habits online for 13 years. And I know a few things about myself and the books I read:

I read a lot more fiction than non-fiction

I read a lot more books by women than by men

Historical fiction is my favourite genre

I read more books by American and British authors than I do writers from my home country of Canada.

But one thing I hadn’t even bothered to think about until last year was the simple fact that almost all the writers I read are white people.

I had a chat on my podcast early last year with two women who are part of an intersectional feminist book club, which got me thinking about intersectionality and diversifying my reading list. So I decided that in 2018, I would make a conscious effort to seek out books by writers of colour.

I followed more black, Asian, Latinx and indigenous writers on Twitter, and when I saw a mention or review of a book by a non-white writer that sounded like something I’d like to read, I sought it out and read it.

The result, not surprisingly, was that I read a lot of really great books I might not have discovered otherwise.

Of course, there’s no need to worry about white people: because “white” is so much a default in our literary culture, my fellow white folks are doing just fine on my bookshelves. Of the 100 books I read last year, 69 were by white writers; 31 were by writers who (to the best of my knowledge) identify as people of colour. And as a result, I discovered some wonderful books that simply wouldn’t have come to my attention if I hadn’t been looking for them.

I love fantasy, but I’m very picky about it. Seeking out writers of colour led me to S.A. Chakraborty’s marvellous City of Brass. I’m a big fan of a historical saga that plays out over generations, but would I have stumbled across Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing by chance? A contemporary family drama rife with tension and secrets? There was Fatima Farheen Mirza’s A Place for Us just waiting to be discovered. How about a good modern-day twist on Pride and Prejudice? There are thousands of them out there, but few with a fresher taken than Uzma Jalaluddin’s Ayesha At Last — unless it’s Ibi Zoboi’s Pride. And if I hadn’t been looking for books about the refugee crisis from the perspective of communities who’ve lived through it, would I have discovered two wonderful refugee stories, each with a weird and lovely twist of magical realism: Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar’s The Map of Salt and Stars and Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West?

And those are just a few of my discoveries.

The obvious takeaway: there are books you’ll never discover if you’re not specifically looking outside your usual shelves. And to me, this is the only possible response to people who critique any kind of “affirmative action” or “diversity programs” by saying, “Well, I don’t look at colour/gender/disability/etc … I just hire/read/invite the BEST PEOPLE, regardless of identity.”

We’d all like to believe we do that. That we hire the best people, read the best books, invite the best people to present at our conferences and events. But the thing is: the best people are everywhere. And almost all of us have preset defaults as to where we look.

I’d like to think I read “the best books.” But in fact, my perception of “best” is heavily skewed towards fiction by white women writing originally in English. That’s what I’m used to, so that’s what I see and what I read. It’s like a I have a set of bookshelves that has been built for me — by a combination of the culture I live in and my own innate preferences — conveniently located at eye-level, like the bookstore shelves where they place the best-sellers face-out so you see them as soon as you walk through the door.

The fact is, there are enough good books on that White Women’s Fiction bookshelf to keep me reading for the rest of my life, without ever needing to move away from it. It takes effort for me to walk into other sections, search through unfamiliar spines, bend down to those shelves that are near the floor when you’ve got creaky middle-aged knees like mine. But there are great books waiting there.

I’m not in the position to hire people, or to invite people to speak at conferences. If I were, I’d like to believe I could apply this same effort to intentionally diversify my world, that I do to my bookshelves. I like what that openness has brought me.

If you only look at the few shelves you have at eye-level, you’ll never see the rest of the treasures waiting in the stacks.

February 3, 2019

Problematic Yearbook Photos (or, I was a horse’s @ss in college)

[image error]

Upon learning that the governor of a southern US state became embroiled in scandal this weekend over a college yearbook picture showing him either in blackface or in a KKK hood, I did what any sensible person would do. I started thinking back over my own yearbook pictures to see which ones would be incriminating in case I ever run for public office.

There are no pictures of me in blackface. But there is a picture of little white me standing next to three other white people who are wearing blackface.

The year was 1978. Our Grade 8 class was performing a Christmas play about a kind middle-class family who give their Christmas presents away to a poor neighbour family. In the play, the poor family was black.

This was St. John’s, Newfoundland, then (and possibly still now) the whitest place in North America, where 98% of the population was descended from English and Irish fishermen. We did not have any black kids to play the Poor Black Family. I had, at that point, never met a black person.

One thing we did have was a lot of Poor White Families. Probably half the kids in that play came from families that were receiving social assistance. I have no idea why our teachers thought blacking up three white kids with shoe polish was a better solution than just having the poor family be white.

But it happened. And there’s photographic evidence. Which I will not post here.

I have, however, posted (above) slightly edited pics from an event a few years later in which I (kind of) appeared.

We’re up to 1984 (the same year as Ralph Northam’s yearbook photo). I was attending a small Christian college in the US with a wonderfully diverse student body from around the world. I now had non-white friends! And for a Halloween costume party, four of us decided to dress up as the Lone Ranger, Tonto, and Silver.

I was the back end of Silver.

We had a blast. We won first prize in the costume contest. Then we went and crashed a house party hosted by some more popular students, realized they were about to sit down and watch Nightmare on Elm Street on VHS, and peeled out of there because we were all scared of horror movies. But that’s not relevant to this story.

What’s relevant is: Tonto’s costume.

We went full-on Native American stereotypes – braids, moccasins, face paint, the lot – but we also wrapped Tonto in a sari. Because the girl playing Tonto was Asian, and we were (in our college-aged minds) making a clever satiric comment on the idea of “Indian” and Columbus’s huge error. See, Tonto was, like, an Indian, but not that kind of Indian. (The girl playing Tonto was not either kind of Indian). We were using an offensively stereotypical costume, but we were doing it ironically. We thought this made it OK.

In the photo above, I’ve replaced Tonto’s face with an emoji that approximates her facial expression. This means you miss seeing her face paint, which was (to use two terms we wouldn’t have used in ’84) both on-point and problematic. But it also means I’m not going to be the one to sink her campaign if she ever decides to seek elected office.

There’s no need to edit out my face because, again, I spent the whole evening bent over in the back half of Silver, staring at another friend’s backside.

In 1978, at age 13, I knew no black people and was not aware of the racist history of blackface. In 1983, despite all the black and Latinx and Asian friends I made at college, I knew no First Nations people and thought that an ironic Tonto costume was cool. I’m fairly sure that in 1984, the now-governor of the state of Virginia had a pretty good handle on the history of both blackface and the KKK.

I’ve always been suspicious of that saying, “When we know better, we do better.” Probably because so often we know better and we still don’t do better.

But two things are for sure:

We rarely do better until we know better, and

Once we know better, we have an obligation to do better.

And if people who are smart enough to run for public office still can’t figure that out, well …

I may not be the only horse’s ass around here.

January 13, 2019

This Bookshelf Sparks Joy

[image error]

I can’t imagine anything less likely than me sitting down to watch a TV show about tidying up your house, but apparently some furor has been raised lately among those who enjoy such things. Everyone was loving tidy-up expert Marie Kondo, right up until she started telling people to get rid of her books. I think she’s the one who wants you to pick up your possessions and ask yourself if they “spark joy” before deciding whether to toss them or not. I don’t know how anybody has a blender or a toaster left after applying that method, but I can see the problem when it comes to book-lovers and book-hoarders. For us, it’s not just that an individual book sparks joy. Joy is sparked by the mere fact of living in a house that has a lot of well-stocked bookshelves in it. It’s about quality, but it’s also about quantity.

However, I have been, for the last two years, applying a kind of organizational mentality to my book collection. It’s a work in progress, and I’m not there yet, but the contents of my many, many bookshelves are going through some re-evaluation and in many cases replacement.

First, for context, here’s a video I made three years ago when it was briefly trendy for BookTubers to make video tours of their bookshelves. I share this (feel free to zip through it on fast-forward) to give you an idea of just how messy, random and oddly-stocked my shelves are).

Some of my bookshelves are still as messy and random as they were in that video, but others, particularly the highly visible ones in my living room have, as you can see in the picture at the top of this blog, undergone a change. I haven’t been following the Marie Kondo method; I’ve been following the Gloria Pritchett method, as inspired by Sophia Vergara’s character in Modern Family and explained in this blog post I wrote a year and a half ago. “Why isn’t all your underwear good?” is my guiding principle now for a lot of things besides underwear, and I someday hope to get to the point where all my books are “good” — that is, I’m only giving shelf space to books I actually want to have in the house.

One of the ongoing issues with my bookshelves is that book series, or just sets of individual books by an author I loved, came into my house in haphazard ways. Take, for example, one of the greatest series of all time: Dorothy Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries, some of my favourite books ever. I had the well-worn mass-market paperback of Gaudy Night I mentioned in the video above, that I had probably owned for 25 years and read nearly 25 times. I had copies of three or four other books of hers, all different editions, mostly mass-market paperbacks. Then a bunch of books from the series were missing because I’d original read them as library books and reread them as e-books, so I owned no copies at all.

It was the discovery of a new release of attractive trade-paperback editions of these books (trade paperback being my favourite format for books: mass-market paperbacks feel cheap and flimsy in my hands and hardcovers too heavy and clunky) that sparked a little joy in me and made me think: why don’t I finally get a complete, matching set of all these books? And behold, over the process of a year or so, acquiring them as they came out and as I could afford them, I have them.

Not all of the books in my new collections were new or expensive: I’ve bought the Dorothy Dunnett Lymond & Niccolo books in well-cared for secondhand copies, but again, I’ve made sure they’re all the same edition and match well together, so they’re a pleasure to look at on the shelf as well as reread. Although I still do most of my new reading on the e-reader, my goal is eventually to own a houseful of books that I have loved and chosen, not just a houseful of books that randomly wandered in here for some reason and are taking up space whether I’ve read and loved them or not.

So that’s my little bit of life-changing magic. What do you think about owning, buying, and organizing books? Have you made a conscious attempt to curate your collection? I’d really love to know what other book-lovers think about this.

January 4, 2019

Too Bad to be True: A Social Media Cautionary Tale

A lot of people’s New Year’s resolutions involve social media. Things like:

“I’m going to get off Twitter.”

“I’m going to delete my Facebook.”

“I’m going to set limits on my social media time.”

“I’m going to stay on all my social media outlets but I promise to stop being a horrific ragemonster all the time. Well, most of the time. OK, some of the time.”

I, too, have made my fair share of plans to better manage my online time — sometimes at New Year’s, sometimes not; some successful, some not. But in the wee hours of this morning, unable to get back to sleep and finished the book I’d been reading, I was scrolling through Twitter when the tweet below came up in my timeline and provided me with a perfect example of a resolution we should all make.

[image error]

Now I’m going to guess that a lot of people who are liberal (like me) and ardently pro-vaccination (like me) had a similar reaction to mine at that tweet. Tragic for any young woman to die at 26, how sad for her family, but what a rich and deserved irony in an anti-vax crusader dying of diseases that could have been prevented by vaccines. It’s like that gun rights activist who got shot by her own pre-schooler — how can you avoid a smug smirk at someone so clearly bitten on the ass by their own misguided beliefs?

What stopped me from immediately liking, retweeting, or commenting, was simple human decency: a young woman in her 20s is dead; there were people who loved her; let’s pause a moment before pointing out the rich irony of her death. And it was that moment of decency, of pause, that gave me time to think, “This seems almost too perfectly ironic.” And while life sometimes is too perfectly ironic (see above story about gun-rights activist), I thought I’d take a moment to click the linked news story and see just how on-the-nose the late Payton’s comments about vaccines were, and whether the illnesses she died of were definitely vaccine-preventable. So I clicked.

And — surprise — the linked article makes no mention of Payton’s anti-vaccine stance. Odd, I thought, and did a bit more digging. What I found was that while Bre Payton was certainly a conservative writer and espoused a number of positions that liberals like me would find objectionable, the attempt to categorize her as an anti-vaxxer was based entirely on a single tweet from 7 years ago (when she was 19) that, out of context, could be read either as opposing vaccines or making fun of anti-vaxxers. Not a single other shred of evidence could I find to suggest that she had ever “campaigned against vaccines” or made public statements one way or the other about vaccines (unless someone’s since uncovered evidence of this).

Nor was there any evidence whether she had or had not gotten a flu shot this year, or whether the strain of flu that killed her could have been prevented by this year’s flu shot. And, in fact, the person on twitter (not the one I saw) who originally portrayed her as an anti-vaxxer took down his tweet and apologized after the error was pointed out to him.

Of course, by the time you’ve taken down your tweet and apologized, it’s like apologizing for that match you dropped in the drought-stricken forest. It’s too late, buddy. Your words are out there, and people are retweeting and sharing and commenting like there’s no tomorrow.

It’s interesting, a few hours later, to see what’s happening on Twitter in response to the death of this young woman I’d never heard of until she was dead. Along with the expected condolences and tributes that follow the death of any public figure, there are the also-expected bizarre right-wing conspiracy theorists claiming she was murdered for reporting on the Mueller inquiry, or the anti-vaxxers claiming she was killed by a non-consensual flu shot.

But there are still plenty of my fellow lefties out there perpetrating the belief that she was a vocal anti-vaxxer felled by a vaccine-preventable disease, or pivoting to suggest that because she vocally opposed universal health care (that part is true) she somehow got what she was coming to her. (Sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but even up here in Canada with our generally quite good public health care, people do still die sometimes. We have not conquered mortality).

One bottom-feeding scumbag has even made a parody account using her picture and a version of her name, to comment on her own death.

Aaaannnd it’s right about now that people say, “Yeah, I think my New Year’s resolution is to quit Twitter.”

I’m not quitting Twitter. Yes, it contains a sinkhole of the worst of human behavior, but it also contains Blair Braverman’s sled dogs, and I’m all there for the pups and the jokes and the cleverness.

But I’m not there for the bottom-feeding pile-ons of human tragedy, especially the ones that happen when we share or comment without taking even a moment to think and investigate. It took me five minutes, all told, to dig into the Bre Payton story and see that the original tweet was inaccurate, which prevented me from sharing hate and misinformation. It was time well spent.

We all need to do this more, but I’m speaking particularly to my fellow lefties here. We’re so quick to notice when those on the opposite side of the political fence make this kind of error on social media — whether it’s blowing a non-story into a story to foment fake outrage, or capitalizing on a genuine tragedy to demonize an innocent group of people. But are we vigilant about it on our own side? When I see a story that just seems so believable, so appropriate, so harmonious with the way I want to think the world works — do I share it without taking the time to think?

Years before Twitter or any other part of the internet was invented, as a child in Sabbath School, I was taught three rules that you’re probably familiar with too — three things to ask myself before sharing a piece of gossip or making a comment. They seem more true than ever in the age of social media.

Is it kind? There is nothing kind about immediately using someone else’s tragedy to score your own points. Whether you agree with a person’s politics or not, an untimely death is a tragedy for those who loved that person and not a time to mock them for what they said or did in life.

Is it true? Actually click on the link you’re sharing and read what it says. Check a few other sources. If it’s not true, don’t be a part of spreading misinformation.

Is it necessary? I absolutely believe it’s necessary to spread the word that vaccines are safe and essential for public health — but sharing an unkind, untrue story is not the way to accomplish that.

I learned a lot in about five minutes this morning — about Bre Payton, about the murky depths of Twitter, and about my own prejudices and assumptions. I’m going to work hard to apply those three rules to my own social media use this year. I invite you to do the same.

December 31, 2018

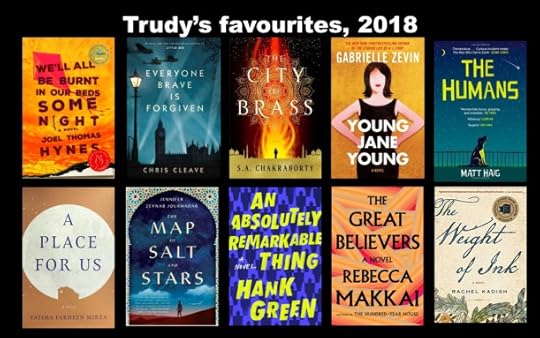

My Reading Year

Well, it’s that time again. I’m looking back at the 100 books I read in 2018, and trying to pick a Top Ten. Some were VERY easy choices — there were books that as soon as I saw them, I knew they’d be among my favourites of the year. Then there was a second tier of books that I really loved, but if included them all, it would be WAY more than ten. (Ten is, of course, an arbitrary number. One year I did a Top Thirteen. But this year I was aiming to trim it to ten).

Well, it’s that time again. I’m looking back at the 100 books I read in 2018, and trying to pick a Top Ten. Some were VERY easy choices — there were books that as soon as I saw them, I knew they’d be among my favourites of the year. Then there was a second tier of books that I really loved, but if included them all, it would be WAY more than ten. (Ten is, of course, an arbitrary number. One year I did a Top Thirteen. But this year I was aiming to trim it to ten).

Some great books got left off this list. But these are ten books I loved this year — all novels, in this case, though I did read some good non-fiction too — and in the end my decision was almost always based on emotional resonance. Which books not only were interesting and well-written, but which did I feel strongly about while I read them, strongly enough that the feeling lingered sometimes months after I finished reading?

Before I link to my reviews of each of these books, a few stats about my reading this year. 100 books is more than I’ve read in any year since I started tracking my reading in 2006, and I’m not sure why, unless it’s that we travelled a fair bit this year and I always read a lot when travelling. For whatever reason, I’m happy to have had the chance to devour so many good books this year.

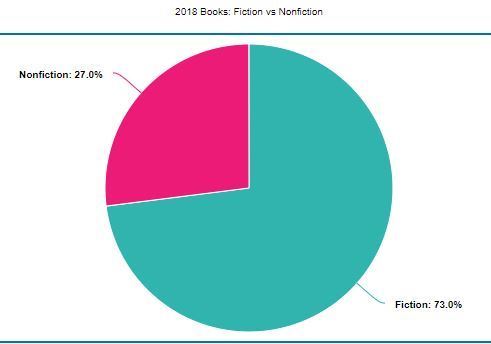

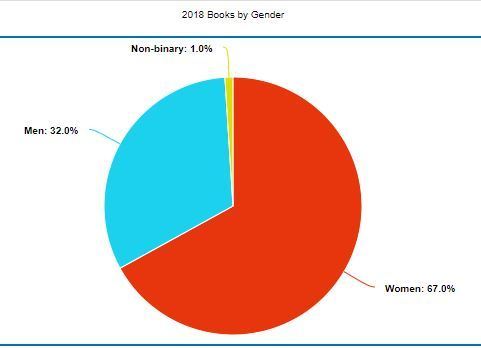

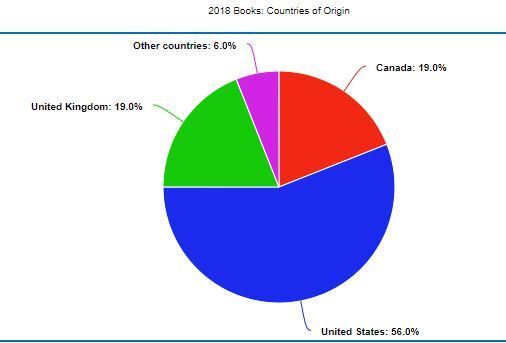

I like seeing trends and patterns, and some patterns remain consistent year to year because that’s just how I read. As always fiction outnumbers non-fiction by nearly 3:1, and books by women outnumber books by men about 2:1 (also, this was the first year I had a book by a non-binary author to include).

Preferring fiction by women is hardly a new trend for me, but I tried to mix up my reading a bit more this year by consciously seeking out more books by writers of colour. This effort introduced me to many wonderful books I would never have found otherwise. In tallying up how this affected my overall reading patterns, I had to make a few judgement calls. “Person of colour” or “non-white” is obviously a bit of an amorphous category, especially for mixed-race writers, but in general I went with how writers identify themselves. I find that I’m still reading a majority of white writers (a bit more than 2:1), but I’m finding a lot more great books by writers of colour, including three of my Top Ten picks (all three by Muslim women, as it happened). Also, out of curiosity, I looked into where the writers I read came from. Again, this is a vague category, because writers don’t always live and work in the same country they were born or grew up in, and again, I tended to go for the most part with where writers are currently living unless they identify themselves as “an American writer living in England” or something like that. I found that I read about the same number of books by British writers as by Canadians, but that I read more American writers than both of those combined — and very few (6) from countries other than the US, Canada, and the UK. (Also, 2 of those 6 were Australian, which means only 4/100 books were by writers from other than English-speaking countries).

Also, out of curiosity, I looked into where the writers I read came from. Again, this is a vague category, because writers don’t always live and work in the same country they were born or grew up in, and again, I tended to go for the most part with where writers are currently living unless they identify themselves as “an American writer living in England” or something like that. I found that I read about the same number of books by British writers as by Canadians, but that I read more American writers than both of those combined — and very few (6) from countries other than the US, Canada, and the UK. (Also, 2 of those 6 were Australian, which means only 4/100 books were by writers from other than English-speaking countries). So, that’s what I’ve been reading in 2018. You can see my full booklist on Goodreads, or on my Pinterest board, or by scrolling back through the full year’s worth of reviews on my book blog, Compulsive Overreader. Here are the links to my reviews of my 10 favourites, in the order I read them throughout the year:

So, that’s what I’ve been reading in 2018. You can see my full booklist on Goodreads, or on my Pinterest board, or by scrolling back through the full year’s worth of reviews on my book blog, Compulsive Overreader. Here are the links to my reviews of my 10 favourites, in the order I read them throughout the year:

Everyone Brave is Forgiven, by Chris Cleave

We’ll All Be Burnt in our Beds Some Night , by Joel Thomas Hynes

The City of Brass, by S.A. Chakraborty

Young Jane Young , by Gabrielle Zevin

The Humans , by Matt Haig

A Place for Us , by Fatima Farheen Mirza

The Map of Salt and Stars , by Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar

An Absolutely Remarkable Thing , by Hank Green

The Great Believers, by Rebecca Makkai

The Weight of Ink , by Rachel Kadish

December 24, 2018

Christmas Rush (ish)

[image error]

Ahh, December 24. Christmas Eve. When I had younger kids and the Christmas rush was more hectic, I used to make a Herculean effort to get everything done by the first week or so of December, so that I would not be doing any rushing around on Christmas Eve. I used to go to Chapters and get a coffee on Christmas Eve morning and sit smirking at all those poor souls still lining up at the checkouts getting their last-minute presents bought.

This Christmas, with two grown kids out of the house, no school concerts to attend, and a generally much more relaxed life, I somehow am one of those people. For various reasons, a lot of stuff got left till the last minute, and I’ve been running last-minute messages on December 23 and even today, December 24.

And you know what? It hasn’t been that awful. I mean, I wasn’t trying to get through the crush at Costco or anything, just dropping into a few stores for a few things (timing it for early morning or late evening when things weren’t as busy), and generally people on both sides of the counter have been friendly and glad to wish each other Merry Christmas or Happy Holidays or whatever. It’s one more reminder that there’s no right or wrong way to celebrate the holidays; do what works and free yourself from too many expectations, even the expectation that you have to be relaxed.

Amid these busy last few days leading up to Christmas, there have been some joyful moments and awful moments, and all the moments in between. In the five days leading up to Christmas Eve…

our college daughter Emma came home for Christmas, bringing back teenage laughter and so much delight to the house.

our musician son Chris sang a heartbreakingly beautiful Christmas song at the musical program we all participated in at church, and then bailed before the service was over so nobody could tell him how great it was and how happy they were to see him.

the aforementioned two offspring had the most bitter and pointless argument I have ever heard between two people who are ostensibly both adults, leading them each to declare the other the worst person they had ever met.

Jason, Emma and I, along with a friend, visited two Christmas house parties in one evening, and saw a great in-house performance of the play Penning the Carol, in which actor Aiden Flynn essentially performs A Christmas Carol as a one-man show, in character as Charles Dickens and everyone in the story, and it was amazing.

The brakes on Chris’s car completely failed and he was totally OK which is what matters but we had to help him out with getting a tow and an emergency brake job right before Christmas.

I joined a friend at her church to be part of an outdoor Nativity scene where I dressed up as a shepherd, along with a bunch of other costumed Christians and two very suspicious sheep who wanted nothing to do with me. It wasn’t even that cold a day, but by the end of two hours I was freezing almost to the point of bursting into tears — but also filled with Christmas joy at being part of such a lovely display.

[image error]

It’s been beautiful, and crazy, and stressful, and peaceful, and everything in between. In other words it’s been, just like holidays always are, more or less of a piece with our everyday lives. Only the heightened expectations (well, and the decorated evergreen in the corner of the room) make it different. Shed the expectations like the tree will slowly shed its needles over the next two weeks, and you’re left with the bare bones of real life, brightened by a few decorations.

However you celebrate, however organized or busy or hectic or relaxed you are — this is it. This is your real life, your real Christmas, your real whatever. Enjoy it.

As for me, I’m off out to do two last messages.

December 17, 2018

Don’t Quit Your Day Job. Or, Do.

[image error]

If there’s one fictional trope in books, movies and TV shows that drives me crazy, it’s this: Character dreams of being a writer. But she needs a day job to pay the bills. So she has to forget about writing and do her soulless day job, but always regrets not writing that novel. OR, she passes on the day job and lives hand-to-mouth while writing her novel, but it’s all great because she’s following her dream!

Either way it plays out, this trope makes me CRAZY. I was once a young writer with a dream, and I got a day job (teaching), and since then I’ve written twenty-some-odd books. I’ve taught every school year since 1986 except for one year I was in grad school, and then the seven-year gap while I was stay-at-home parenting two small kids, while also going to grad school part-time and writing both my own fiction and a lot of contract work for hire. As a writer, there’s been almost no part of my career where I didn’t have a day job.

Four years ago, I made a video about this very thing:

As I tried to convey in that video, different things work for different people, obviously. If you have to have 100% focus on your writing in order to be able to create, and you have someone to support you, or a lot of money in savings, or something else that makes that possible, that’s great. Quit the day job (or never get one!) and make a go of it. But the reality is that virtually every serious writer I’ve ever known has written alongside having a day job for some part if not all of their career. And those who don’t have traditional “day jobs” like teaching or librarian-ing or working in an office, are doing a lot of other things to pay the bills — whether that’s writing educational materials or PR for someone’s business, or teaching writing workshops, or doing something that vaguely relates to writing but, unlike their creative work, brings in a regular paycheque.

So I’ve always been a big proponent of the idea that, while you can quit your day job if you want to/are able to, quitting your day job is not a prerequisite for being a writer, or any kind of creative artists. In the real world, artists have to pay the bills like anyone else, and usually come up with a variety of ways to do so. Sometimes more creativity goes into drumming up jobs to pay the bills than into your actual art (well, that and writing grant applications).

In fact, the reason I went back to teaching in 2005 when my youngest kid went to school was that after seven years of doing various freelance contract work, I was tired of hustling and stringing together contracts and still fitting my own creative work into my “free” time. If I was going to be looking for free time to write, I figured, I might as well go back to teaching, which paid a heck of a lot better than freelance writing and required no hustle whatsoever. And that’s worked well for me for the past 13 years, just as it did for the first 12 years of my teaching/writing career before I had kids.

But now … I’m doing it. I’m quitting my day job.

Well, sort of.

Yep, things have changed a bit since I made that video above. It’s a different stage of life and I’m trying something different. This year, I taught during the fall semester, which is drawing to a close this week. In January, I won’t be back. I’ve taken the winter semester off (my job will be waiting for me again in September though!) to see how I do with being a full-time writer. It will, of course, be a big change financially — only working 40% of the school year means only getting 40% of my pay. (Of course, this is mainly possible because my husband has a job that pays much better than mine, and with both kids moved out our family expenses have decreased).

It’ll also be a challenge in terms of how I use my time. For decades I’ve been fitting writing in around other things. How productive will I be when the other things are gone?

Several years ago, I wrote a blog post analyzing what I got done on a “free” day that I supposedly had to devote full-time to writing, and concluded that I might not actually be that much more productive if I had all day to write. I hope that now that I’ve taken a personal and financial risk to dedicate time to writing, things will be different. I have a lot of projects to pursue and goals I want to accomplish, and I hope I’m going to be disciplined enough to put in the time I need to get those things done.

But there’s no way to know until I’ve tried it. So I’m packing up things in my classroom, making lists of what I want to accomplish in January — and looking forward to this new adventure.

November 11, 2018

100 Years Ago

One hundred years ago today, the guns fell silent.

[image error]

Newfoundland War Memorial. Photo credit: Tom Clift

They fell silent, that is, on the battlefields of the First World War. A last few men died on the morning of November 11, in response to orders that the men at the top had already decided were meaningless. Then, at the pre-arranged time of 11:00 a.m., everyone stopped shooting. It was so simple, after all: just stop shooting.

Of course, the guns started up again soon enough. In other places, and then, twenty-one years later, in the same places. They have rarely fallen silent, ever since we invented guns. Before that, we had quieter ways to kill each other, but we’ve never stopped.

Every Remembrance Day, we pause in our different ways to remember all the dead and wounded in all our wars. We remember on the day that commemorates the end of the once-called “Great” War, November 11, 1918. And after all the bloody conflicts of this century, that First World War still captures our imagination.

It wasn’t the deadliest war of the century. But falling as it did between the invention of the machine gun and the widespread use of airplanes for bombing, it was perhaps the first war with death on such a horrific scale, and the last where that scale was still possible for the human mind to grasp. It was a conflict that illustrated in vivid colours the bravery and suffering of ordinary fighting men, and the vanity and stupidity of those who ruled them. It was a war that need never have been fought: a petty power struggle that cost millions of lives.

Due at least in part to the bungled peace process that followed that November 11 armistice, the “war to end all wars” was followed by its inevitable successor two decades later. This time, Germany was led by a villian of such comic-book awfulness that few questioned the necessity of war, either at the time or in retrospect. The horrors of Nazi Germany, especially the horrors of the Holocaust, were so intolerable that we could forgive or overlook the horrors committed by our “good guys” in the attempt to stop them.

And once again, millions died — brave soldiers, and probably some cowardly soldiers too, and lots and lots of civilians who had never made the choice to go to war, but found war exploding all around them or dropping on their heads.

The power struggles among the victors of that war led to the world I was born into: the world of Cold War, where humans, for the first time, developed weapons theoretically capable of destroying all life on the planet. For forty-five years, while smaller conflicts flared and died and killed around that planet, the great powers played a long game of chicken over who would dare use these deadly weapons.

In the end, they tired of that game. As a species, we seem to have decided it’s less work to destroy the planet by greed and consumption and laziness than by dropping bombs. And largely, we have outsourced the business of killing in large numbers to terrorists and “rogue states.”

We didn’t get rid of the bombs, of course. We kept them around, just in case.

For all the Great Literature it produced, my favourite World War One novel will always be the first one I read, L.M. Montgomery’s Rilla of Ingleside. At the end of that novel, nineteen-year-old Rilla records in her journal the words of her recently-returned soldier brother:

“‘We’re in a new world,’ Jem says, ‘and we’ve got to make it a better one than the old. That isn’t done yet, though some folks think it ought to be. The job isn’t finished — it isn’t really begun. The old world is destroyed and we must build up the new one. It will be the task of years. I’ve seen enough of war to realize that we’ve got to make a world where wars can’t happen.'”

The fictional Jem Blythe speaks these hopeful words in 1919; Montgomery published them in 1921.

In 1921, Adolf Hitler was named leader of the Nazi Party in the Germany.

It’s hard to know what to celebrate, 100 years after the end of the war that began all the other wars. In that century we have made so much progress as a species. Diseases have been eradicated. Advances in communication and transportation have made possible things that were only dreams before. Huge groups of people who were considered barely human in 1918 now enjoy the same rights under the law as wealthy white men did in 1918. People are better educated. Workers have more rights. Poverty and infant mortality are declining almost everywhere.

And yet. The climate is changing and we can’t be bothered to figure out how to stop it. And in the face of a more and more globalized world, where we all have to deal with each other, an unimaginable number of people in “free” countries (sometimes whole governments) have responded by turning inward: condemning the Other, boosting an imagined racial superiority, building metaphorical and literal walls. In World History, I teach “nationalism” as a deadly underlying cause of World War One. After a century of mostly moving away from me-first nationalism, more and more countries and leaders — including the president of the United States — are now proudly declaring themselves “nationalists.” “Our people first, and screw the planet and all those other, lesser people on it.”

I was raised to believe two stories about the history of the world. One was taught to me in church, the other by the surrounding humanist culture. Both were, in their way, hopeful.

The church taught me that the world would get worse and worse and then God would dramatically intervene to save us. The culture taught me that the world would get better and better and we would solve all our problems and save ourselves.

Looking back 100 years to the day the guns went (briefly) silent, wondering about those soldiers who died to help build a world they could not imagine, I can find hard evidence to support both beliefs — which means neither feels completely true. The world is getting much, much worse, and much, much better at the same time, and while we have not seen evidence that God is going to dramatically intervene, we also, to be frank, haven’t shown much sign of saving ourselves either.

There are plenty of people who believe neither story: who simply accept despair and defeat. Who look back at 1918, and all the war since, and say that it will never get better. That we can rely on neither divine help nor human goodness to break the endless cycle of violence and hate.

100 years after the horror of the trenches…

70 years after Kristallnacht…

29 years after the Berlin Wall fell…

A day or a week after whatever the last horrific headline was …

…it’s hard to be hopeful. Hard to know, sometimes, what my hope is based on.

But I still hope. I don’t always know why, or in what. But the hope I hold to is the only way I know of not breaking faith with those who sleep: in Flanders Fields, and in cold graves at the bottom of the ocean, and in Auschwitz, and in Hiroshima, and at Ground Zero, and in Afghanistan, and in every place humans have slaughtered other humans for the past 100 years.

I try to keep faith.