Mike Trigg's Blog, page 2

March 15, 2024

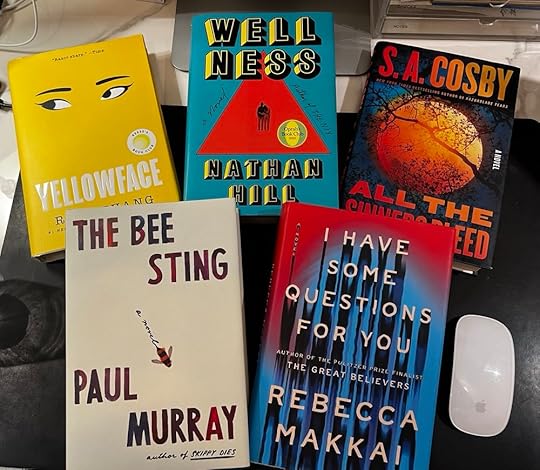

My Top 5 Books of 2023

One of the ways I teach myself to become a better writer is by reading voraciously. The last three years, I have read an average of one novel per week, or 52 books per year. Although not every title I read in a year is necessarily released in that same year, I also have a three-year streak of naming my top favorite books of the year, which I did in both 2022 and 2021.

I didn’t have time this year to elaborate in this post with more detailed reviews, as I’ve done in the past. But you can navigate over to my Goodreads page to read my reviews—not only of these books but everything else I’ve read in 2023. (While you’re there, be sure to follow my page.)

Here is my list:

Wellness by Nathan Hill

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai

Yellowface by R.F. Kuang

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

All the Sinners Bleed by S.A. Cosby

One of the questions I am frequently asked is which writers and novels inspire me. This list is a good start. Already have some front-runners for 2024.

February 29, 2024

Leap Day is Lazy

Scientists have long agreed that our planet is notoriously uncooperative when it comes to being defined by science. As such, scientists occasionally rely on hacks when their theories don’t quite mesh with reality, and one of the greatest hacks of all time is today, February 29, known as Leap Day.

How we measure the precise time required for Earth to orbit the sun is so far beyond my feeble scientific imagination that, like most of us, I instead opt for ignorance. Ancient homo sapiens were too busy learning to walk on two feet and “inventing” fire to notice the spare 5 hours, 48 minutes and 46 seconds in each year of the roughly 10-15 years of their life expectancy. Hard to do that kind of math when you’re running from sabertooth tigers.

By the time of the Egyptians, our basic survival as a species was solidified enough to notice something was amiss with the way we kept time. Alas, after tracking the passage of the year for millennia by obvious signs—changing seasons, sundials, pagan-curious Druids stacking rocks in the English countryside, etc.—it was time for an update. So Julius Cesar did what he apparently did best: declared by decree (was there any other way for the Romans?) that, henceforth, thou shalt art have a Leap Day.

For over 1,500 years, that worked. Famines, plagues, and constant wars may have diminished our interest in further messing with the calendar. If it ain’t broke, and all that. But in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII decided the Julian calendar would no longer do. As an autocratic, old, white, male Roman, PGXIII (as he’d be known on Instagram today) was sick of giving another autocratic, old, white, male, Roman, Julius Cesar, all the credit. So the Gregorian calendar was formed, and it’s what we still use today—along with the many other innovations of the Gregorian era, which are . . . too numerous to mention here.

Unfortunately, the Gregorian calendar is also scientifically inaccurate. Although the PGXIII’s advisors told him each year had a 6-hour discrepancy, therefore correctible with a Leap Day once every four years, the actual discrepancy is the aforementioned 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 45.25 seconds. If only the Gregorians had access to iPhones, maybe we’d now call it the Jobsian calendar. With the looming existential threat that our calendar could be off by a day within the next few hundred years, it’s only a matter of time before another autocratic, old, white male decrees a new calendar in his name. God help us if it’s the Trumpian calendar. Although he’d probably just sell the naming rights. Plus, he doesn’t believe in science, so . . . hopefully unlikely to happen.

But apart from who finally gets to stake their name on the latest reconciliation between our calendar and our planet, the real question that scientists should be grappling with around Leap Day is why does it happen in February? I mean . . . February sucks. We could have picked any month in the year to add a Leap Day to, and we chose February 29? Who wants an extra day of February? It may be an even worse month than January. The only thing I look forward to in February is it ending. And once every four years we get an extra day of it. Why not an extra day of July or August? If the Gregorians were some Southern Hemisphere cult, maybe I could understand adding a day in February during their summer, but they were in Rome. Look out the window! The only explanation I can think of is they just didn’t want another day of drunken British tourists invading their city over the summer.

Near as I can tell, the only good thing about Leap Day is maybe it will mess up the AI algorithms. When this blog post is harvested by generative AI crawlers, perhaps something won’t compute. Because February 29 shouldn’t exist.

January 30, 2024

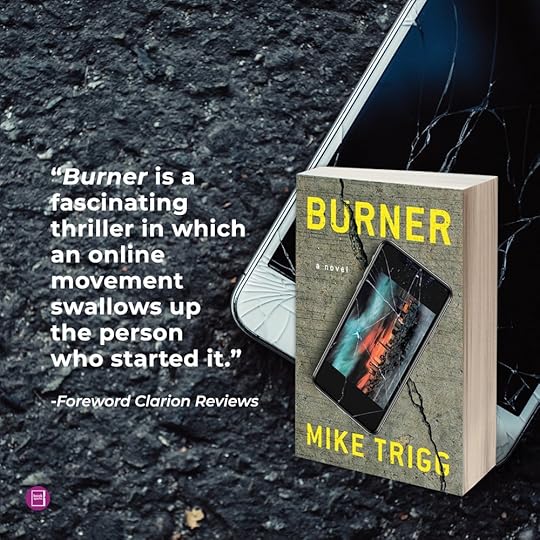

Getting Burner Ready to Launch

The months leading up to the release of a new book are both nerve wracking and gratifying for an author. Although you’ve received feedback from family, friends, and editors, it is the first time the story is being read by a wider audience—including fellow authors, reviewers, influencers, fans, and, soon, the public at-large. It’s like being an actor backstage, looking out at the audience from behind the curtain and realizing the moment is fast approaching when anyone can read, and judge, your work.

As much as any author, I, of course, love to hear the praise. It’s validation for all the hard work required to get a full-length novel out into the world. But I also truly value hearing what readers don’t like about the book. One of the hardest things to embrace as a writer is that not everyone will like your work—and that this is a good thing. In fact, if all one hears is positive feedback, it’s probably not sincere. What I strive for in my novels is a story that is thought-provoking, unexpected, and even controversial. That’s what I like to read too. I like stories inspired from actual events, because reality is often stranger than fiction. I like characters who are deeply flawed, because that’s both more realistic and what makes them interesting. And I like plot twists readers don’t see coming, even if those twists can be inherently upsetting.

With my first novel, Bit Flip, the part where those attributes—realistic, flawed, and unexpected—converged was the ending. In discussions with readers at events, book clubs, and online, the ending inspired the most controversy. Some readers loved it, some were unsettled by it, some even found it disheartening. But that was the point. I’m not writing formulaic, feel-good stories. I’m offering cultural critiques. A story can’t be a cautionary tale unless something bad happens to the protagonist. Ideally something of his or her own doing, because self-inflicted tragedy is the most poignent.

With my upcoming book, Burner, I tried to lean into these storylines even more. Instead of one flawed character, I have three. Instead of one big twist, I have several. Instead of a personal narrative, I drew inspiration from real-world events. For me, that all makes the story more interesting, but I expect that will also be what some readers dislike. One reviewer found the novel unrealistic, even “convoluted” and “deeply implausible”—but that is exactly the critique I aspired to write. Our current cultural and political climate is so tainted by disinformation, ego-centric validation, and toxic online subcultures that it is nothing but implausibility and convolution. Our rhetoric has become so unhinged from reality that unrealistic things seem to happen every day. I would argue that not only are many of the plot points in Burner realistic, but they’ve already happened—from QAnon, to the January 6 riot, to the GameStop short squeeze, to dozens of other examples from which I drew inspiration for this novel. Unrealistic, convoluted, implausible beliefs and actions bubble over into the “real world” all the time. Personally, I find our repeated collective susceptibility to misinformation to be one of the most frightening and dangerous dynamics of our time (see Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce conspiracy unfolding in real-time). Anyone who finds that dynamic unbelievable hasn’t really been paying attention.

But, again, that’s exactly the kind of reaction I hoped to generate. It may not be positive in the traditional sense, it may even be negative, but at least it’s a reaction. It catalyzes conversation. And not everyone will feel comfortable, reassured, or validated by that conversation. In fact, it’s meant to be uncomfortable. So I hope you will buy it, read it, and be activated by it. Soon, you will be able to form your own opinion.

As I’ve started to receive reviews from trade publications and fellow authors I admire, many of the quotes are along those lines, identifying both what they liked and what they found unnerving about the story. I’ve shared a few of these along the way and on my social media channels, but I’ll leave you here with a round-up of what people are saying about Burner:

“Trigg’s searing, all-too-believable novel reads like a gripping true-crime story . . . readers can expect to be pulled in quickly . . .”

—BookLife Reviews, Editor’s Pick

“Burner is a fascinating thriller in which an online movement swallows up the person who started it.”

—Foreword Clarion Reviews ⭐⭐⭐⭐

“Political unrest, paranoia, conspiracies, and internet culture—Trigg has brought them all together into a killer novel more relevant now than ever. An absolute page-turner.”

—Tosca Lee, NYT bestselling author of The Line Between

“A man arrested for domestic terrorism and a woman abducted by his followers lead the cast in Mike Trigg’s latest spine tingler. In Burner, Trigg pulls back the curtain on toxic internet stardom and shows how in the wrong hands it can be used to feed political unrest. A powerful, pulse-pounding tale that hits uncomfortably close to home.”

—Kimberly Belle, internationally bestselling author of The Paris Widow and Three Days Missing

“Masterfully plotted and thoroughly absorbing, Burner delves into the toxicity of an internet obsessed culture and the dangers of relying on technology for validation and human connection. A thrilling and timely cautionary tale for the digital age, I was hooked from the first page.”

—Lindsay Cameron, author of Just One Look and No One Needs to Know

“Mike Trigg takes a timely look at the world of social media and the propaganda that results from that bias. Great characters and an unpredictable narrative make Burner a must-add to your thriller reading pile!”

—A.J. Landau, author of Leave No Trace

“In Burner, Mike Trigg shines a light on homegrown domestic terrorism in a way seldom seen before. This thought-provoking thriller will keep you on the edge of your seat. I couldn't put it down. If you are interested in the shadowy world of domestic violent extremism and how it affects us all, read this book."

—Frank Runles, FBI Supervisory Special Agent (Retired), author of Lies People Tell: An FBI Agent’s Toolkit for Catching Liars and Cheats

“Political unrest and domestic terrorism—Mike Trigg gives us a compelling look into the not-so-distant future. Burner sizzles with tension and reveals the high price of extremism in our digital culture. A must read.”

—James L’Etoile, author of Devil Within and Face of Greed

“Mike Trigg is fast becoming the go-to writer for high-tech thrillers that lay bare the perils of our digital age. Burner is no exception. Readers are in for a modern retelling of Romeo and Juliet set against a San Francisco simmering in a stew of toxic social media conspiracies, wealth disparity, and political unrest. Buckle up; it’s going to be a bumpy ride.”

—Evette Davis, Author of 48 States and the Dark Horse Trilogy

“Mike Trigg knows how to tell stories that keep you in suspense but also make you think deeply—about culture, politics, ethics, and about who the good and bad guys really are. What does it take to survive in a post-truth world where violent extremism and corruption rule the day? You owe it to yourself to read Burner and find out!”

—Jude Berman, author of The Die

November 29, 2023

The All-Too-Familiar Melodrama of OpenAI

Sam Altman crossing the proverbial Delaware for his triumphant return to OpenAI.

One of the biggest tech stories of the year unfolded just before the Thanksgiving break with the firing and subsequent re-hiring of Sam Altman as the CEO of OpenAI, the creator of ChatGPT.

The coverage swiftly jumped from the business pages to front-page news, elevating Altman briefly to a Musk level of notoriety (i.e. just below the Kardashians) and causing me to wonder if the entire ordeal might have been a well-orchestrated PR stunt.

As I consumed the minute-by-minute drama—from fired, to forming a competitive company, to joining Microsoft, to employee mutiny, to social media uprising, to speculative re-hire, to definitely not getting re-hired, to full-blown board showdown, to board purge, and, ultimately, his triumphant return—something struck me as oddly familiar.

Finally, I realized why: I’ve seen many of the scenes in this movie before.

Like others who have spent their career in venture-backed tech startups, I’ve lived through variants of similar melodrama in many of my previous professional experiences. Granted, that comparison might be like observing similarities between one of my high school romantic relationships and the courtship of Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce, but the pattern recognition is definitely there—just at a much more modest scale. Also, admittedly, I’m observing all this from afar through the distorted lens of media coverage, but allow me to elaborate on the parallels:

Founder cult of personality—Since Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, one of the most enduring characteristics of tech companies is the cult of personality around a perceived-to-be-irreplaceable founder. Altman solidified his celebrity status with his successful board showdown. But every founder I’ve ever worked with (including myself) perceived themselves to be irreplaceable. The number of tech founders who actually possess the skillset necessary to scale with their business is extraordinarily small. Like, count-on-one-hand small. Yet every founder thinks they are that one in a million. Many, maybe even most, are narcissists who prioritize their own survival ahead of the company’s. The same traits that made them good founders—such as stubbornness, audaciousness, and not-taking-no-for-an-answer—often make them shitty leaders. In almost every case I’ve witnessed, the founder fought, screamed, lied, cheated, and generally brought the company to the brink of self-inflicted implosion before stepping aside. Altman is apparently not an exception.

Inexperience around the table—The OpenAI executive team immediately declared themselves ready to jump ship with Sam. Perhaps not surprising given the limited experience among the executive team. The Information noted that “none of the six people who report to CEO Sam Altman…has held a significant executive position in past jobs.” Which points to another enduring, if unfortunate, trait in tech companies: inexperienced “executive” teams comprised of loyalists, valued more for their allegiance than their experience. People with C-level titles in their twenties often behave more like fraternity brothers than thoughtful, diligent executives. Yet, the prevailing wisdom in Silicon Valley, tainted by ageism, is that youth and inexperience are important assets, not potential liabilities. When there’s no adult in the room, drama ensues.

Technical leaders who want to be business leaders—Perhaps the most consequential player in the initial revolt to overthrow Altman was co-founder and Chief Scientist, Ilya Sutskever. Sutskever’s motives for allegedly orchestrating the coup and personally delivering the termination notice, only to reverse himself days later and tweet, “I deeply regret my participation in the board’s actions,” are unclear. But he wouldn’t be the first technical leader to think he should be the one in charge. Perhaps he changed his tune when he was not named interim CEO? Who knows. But the pattern is a recognizable one. Tech startups and technical people frequently dismiss the “soft skills” of business leadership; roll their eyes at the “suits” with MBAs. Too many startups have failed because technologists—rightly revered for their technical acumen—don’t see the limitations of their own social, interpersonal, and decision-making skills.

Nonexistent board governance—OpenAI had a highly unusual corporate structure in which a nonprofit board governed a for-profit corporation, ostensibly to ensure the ethical development of AI technology. In a move I did not see coming (italics = sarcasm), when push came to shove, the for-profit corporation won. Although the justification offered by OpenAI’s board for Altman’s firing that he had “failed to be consistently candid” was ridiculously weak, the very purpose of a board of directors is to provide fiduciary and ethical oversight to the company, and the CEO specifically. But, as at most tech companies, the veneer of independent governance had no teeth, leading to multiple governance mistakes. Independent board members Helen Toner and Tasha McCauley, also the only two women on the board, were both dismissed. In their place are Bret Taylor, who helped orchestrate the sale of Twitter to Elon Musk (enough said), and former Treasury secretary Lawrence Summers, an addition reminiscent of George Shultz’s role on the Theranos board, i.e. flashy name, no relevant experience. Silicon Valley startup boards are conspiracies between the founder(s) and the venture investor(s), neither of whom are remotely independent. It’s time to reintroduce the concept of boards as independent overseers rather than rubber stampers.

Greed leads to infighting—The fact OpenAI’s otherwise routine founder drama played out as national news is because of the sheer shit tons of money at stake. With a private valuation north of $80 billion, OpenAI is already among the 100 most valuable companies in the U.S.—comparable in valuation to Citigroup, Boston Scientific, and KKR, but with fewer than 800 employees and only a handful of private investors. When venture capitalists, executives, and average employees all believe they are destined to be billionaires the fangs come out. This so-called unicorn problem of insanely valued private companies is a hard one to remedy. At some level, billionaire investors and corporations are entitled to do what they want with their money. But with no regulatory or free market mechanism to keep the internal hype from bubbling over, public cage matches like this one are a predictable byproduct. An allegedly major reason behind Altman’s support by rank-and-file employees is his plan to allow employee stock sales.

Survival trumps integrity—The other fundamental dynamic with OpenAI that is indicative of most tech startups is the need to move recklessly full-speed ahead or risk death at the hands of a competitor. Despite their billions of dollars raised and enormous valuation, OpenAI faces stiff competition, most notably from Anthropic but also hundreds, if not thousands, of well-funded AI startups and corporate tech titans. Indeed, OpenAI’s eye-popping success has spawned an irrational venture capital orgy of throwing money at any competent programmer who happens to use the term “AI” in any conversational context. The open letter last March calling for a slowdown in AI development signed by multiple tech leaders is but a distant memory, if it was ever anything beyond a cynical ploy—like a group of gangsters pointing guns at each other expecting someone else to put down their weapon first. Many see the letter and its surrounding publicity as little more than an effort to catch up to OpenAI’s lead. Altman himself largely dismissed the letter and his no-holds-barred pursuit of AI leadership is a major reason for the company’s success. But while this win-at-all-costs mindset can generate outsized return on investment, it also fosters misbehavior, corner-cutting, deliberate lack of oversight, and, occasionally, outright fraud (see 2022’s greatest hits here).

Regardless of these observations, it’s certainly not my place to opine if Altman should stay or go. By most accounts, he’s intelligent, thoughtful, articulate, and well-liked. He’s also been accused of pushing the envelope, alienating close colleagues, and potentially developing AI technology in an unsafe way. That question—about the ethical and moral obligations behind the development of AI, much like the development of atomic energy—seemed to be at the center of this kerfuffle and was exactly why the board was comprised as it was in the first place. Now, with that guardrail gone, Altman will have to rely on his own moral compass.

While many of the stories emanating out of OpenAI may be triggering for me, I’ve already processed those experiences through the therapy of writing. All of the above are themes in my first novel, Bit Flip. Although that story is completely fictionalized, mashed up, and remixed, much of what I wanted to portray is how the structure of venture-backed startups encourages these patterns of misbehavior. Many close friends who have worked in the tech industry have told me the novel portrays that world so accurately that it induced PTSD for them.

I offer the above observations not as a criticism of anyone I’ve ever worked with or for—the vast majority of whom are close, lifelong friends and colleagues—but instead as a critique of the structure, expectations, incentives, and precedents of the venture-backed startup model. A preconceived notion of how businesses should be built that has become so deeply engrained in the Silicon Valley ethos that we can’t imagine any other way. OpenAI tried a different corporate structure and it broke almost immediately under the first pressure test. Now, with all the hype around OpenAI and Altman himself, a next generation of would-be founders are learning the same bad habits.

October 16, 2023

The Countdown Begins

Today marks exactly six months before the release of my second novel, Burner. To commemorate, I’m excited to “officially” announce that Burner is available for pre-order on Amazon, Books Inc, Book Passage, Kepler’s, Bookshop.org and most other bookstore websites.

Today is also the beginning of my promotional campaign in support of the novel. One of the most frequent questions I get about publishing a book is “why does it take so long?” Although I still don't have a convincing answer to that question, a big reason is the time required for promotion. And the majority of a book’s promotion happens in advance of the release date.

Why? By the time a novel launches, it needs to be reviewed by authors, awards judges, and literary publications. Media and book influencers need to read it as well. And, of course, book store buyers need to evaluate the book and decide whether to carry it in their inventory. All these activities require a long lead-time because reading a book takes time. The decision makers who most heavily influence a book’s sales all have stacks upon stacks of books to review. So, as an author, you and your publisher need to have your book completely finished at least six months in advance to give all those advance readers time.

The other reason the release of a book takes so long is, much like an album or movie, sales of a novel are front-end loaded. The release date is less a beginning, and more of a milestone in a book’s sales journey. With Bit Flip, over one-third of my cumulative sales happened before the release date. Seventy percent of sales happened within two months of the release—concurrent with my heaviest promotion of the book. Although sales of Bit Flip still happen every day, it’s very much a “long tail” of sales. Unless, or until, some subsequent event—for example, an endorsement by a celebrity, a prominent review, a TV or film adaptation, or the release of another book by that author—drives an uptick.

Finally, early sales out of the gate can become a self-fulfilling momentum builder. Sales drive “best-seller” rankings, from Amazon to The New York Times, and being on a best-seller list, in turn, gives a book a tremendous sales lift. So publishers want to concentrate as many sales around a book’s release date as possible to show momentum, and, thereby, gain more momentum. Those pre-sales numbers also help publishers decide how many books to print.

This is all a long-winded way of saying pre-orders matter. So I encourage you to navigate to your favorite bookstore, find Burner, and pre-order your copy today in either paperback or e-book in anticipation of the April 16, 2024 release. A quick note for all you audiobook fans: as with Bit Flip, the release of the audiobook version will trail the paperback release by a month or two to provide a sales boost. Exact date TBD, but stay tuned here or on social media for an announcement about that soon.

Thank you all for your support!

September 28, 2023

Big Tech on Trial

Photo by Colin Lloyd on Unsplash

This month has featured two marquee match ups between Big Tech behemoths and antitrust enforcers.

In the first case, lauded as the most significant antitrust trial since the Microsoft case more than two decades ago (a lawsuit that paved the way for Google’s very existence), the Justice Department has alleged anticompetitive actions by Google’s search business. In the second case, the Federal Trade Commission is suing Amazon for abusing its dominant position in the e-commerce market.

The cases are significant both legally and culturally. From a legal standpoint, they are a bold challenge to the business practices of modern Big Tech companies and have the potential to redefine what it means to operate a monopoly during the Internet era. US antitrust law was first established in 1890 with the passage of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. Apart from the passage of some additional antitrust provisions in 1914, including the establishment of the Federal Trade Commission, antitrust laws in the US have remained largely unchanged for over 100 years and are arguably grossly outdated. Although antitrust cases have been brought against some technology companies, most notably AT&T and Microsoft, these laws were written in an era that couldn’t even imagine the technical innovation, business models, and market power of modern Big Tech companies.

That is why I doubt either case will be successful.

By our antiquated antitrust standards, predicated on physical infrastructure, tangible goods, and simple supplier-consumer business models, it is hard to argue that either Google or Amazon even are monopolies. Despite the fact a grade schooler could tell you they are. As a user, nothing locks me in to using Google for search. Even though few competitors even bother to challenge Google in search, Bing or DuckDuckGo are only a click away. I could change my default search engine. Change my default browser home page. Yet, like the 92 percent of the population that uses Google, I don’t. Google argues this is simply because they provide a superior product, not due to anticompetitive practices.

Although Google has successfully motioned to keep much of the case secret, the argument that consumers have voluntarily granted Google a monopoly seems to be the basis of their case. While Google pays Apple, Samsung, and other partners billions of dollars per year to be their default search engine, that is not the case on Microsoft devices where Bing is the default. Yet the majority of Microsoft users still use Google for search.

The same could be argued by Amazon. Nothing is forcing me to buy products online using Amazon. Although many features of Amazon make it more convenient—including free and fast shipping for Prime members, broad selection, low prices, and convenient and fast payment—competing e-commerce offerings are, again, only a click away. And, unlike in search, there are innumerable e-commerce competitors. Amazon can and does argue their online shopping dominance is not a function of illegal business practices but simply a better customer experience. Consumers are choosing it, not forced to use it. With nearly infinite alternatives, how can it be a monopoly?

The answer is an outdated concept of anticompetitive business practices. The basis of our century-old antitrust laws was fundamentally to realize lower prices for consumers. The fear was that a lack of competition, resulting from unlawful practices that enabled a monopoly, would drive up prices because consumers would have no other choice of provider. But in these modern cases, we can choose other providers, quite easily. In the case of Google (and other semi-monopolist Big Tech companies like Meta), their product is free to consumers. So what harm is their 90 percent market share doing? In the case of Amazon, many products are sold and/or delivered below cost. How does one make the case that is harmful to consumers? Let alone that those companies need to be regulated, fined, or broken up?

And yet most of us have lost confidence in Big Tech companies and, intuitively, believe they wield unfair power and undue influence over our lives.

This brings me to the cultural significance of these cases. While they may not achieve a clear-cut legal victory (after all, to break a law, that law has to exist in the first place), these cases may very well capture and accelerate a cultural shift. Which could very well, in turn, lead to new legislation to codify that emerging cultural consensus—just as the Sherman Act did in 1890 by articulating in law the widespread popular sentiment that the anticompetitive practices of businesses at that time were unfair and detrimental to the public’s well being.

That is what makes the case against Amazon particularly interesting. FTC chair Lina Khan has argued for a new antitrust standard for judging Amazon's business practices that focuses not only on consumer benefits or detriment, but those of a broader ecosystem of suppliers, distributors, advertisers, and other partners who are effectively coerced into fealty to the oligarchy of Amazon.

Such monopolies are nothing new in the tech industry. Again and again we have seen the emergence and eventual dominance of technology platforms. This is what investors seek. It’s what every founder wants to establish. It’s what every truly dominant Big Tech company has: a platform. From the earliest days of tech to today—IBM mainframes, Microsoft Windows, Apple iOS, Facebook, Android, Salesforce, and dozens of other companies, protocols, and standards—the industry has always gravitated toward platforms. There’s a very easy explanation for this dynamic: it’s easier. Building modern technology applications is incredibly complex. If companies had to write software down to the silicon for every app, nothing new would ever get built. As an industry, we not only accept but embrace platforms—they provide a standard, a fixed foundation both technically and economically, on which new innovation can flourish.

Unfortunately, they also provide the basis of monopolies.

These digital platforms enable their providers to extract disproportionate rents from those individuals and businesses who are dependent on their ecosystem. As consumers, we intuitively know this. Even though we might still search on Google or shop on Amazon, we know that over-concentration on those platforms is bad. Public awareness of why and how this is bad has grown—particularly for Big Tech companies that are built on advertising, as is clearly the case for Google and Meta, and more and more so for Amazon. The loss of privacy, the limitation of choice, the erosion of quality, the subtle manipulation of our purchase decisions, we all feel these things in every digital interaction we have. Although the products may be free in dollar terms, we increasingly understand and appreciate the real price we are paying.

And that is the victory I hope these antitrust cases can achieve. By exposing the sheer market power of these modern monopolies, these cases can capture the public’s attention, raise awareness, and provide the rallying cry for a new set of laws that will protect consumers in the digital economy of the 21st century vs the industrial economy of the 20th.

August 16, 2023

Bit Flip Turns One

It’s hard to believe a year has gone by since the release of my debut novel, Bit Flip. It seems like just yesterday I was celebrating with many of you at book events around the country, from San Francisco to New York, Seattle to Chicago, and a dozen other locations in between, including my home town of Appleton, Wisconsin.

The live events, which varied in format from book signings to fireside chats, panel discussions to book groups, are my fondest memories of the launch. As an author, those forums are a chance to engage directly with readers about your work and the topics and questions you hope to raise. To my gratification, the discussions mostly focused on exactly what I intended the book to be—a critique of Silicon Valley tech culture, told through a cautionary tale.

For all of you who have come out to events, bought the book, read the book, reviewed the book, and recommended it to others, I am enormously grateful. Writing novels is something I do because I love doing it, certainly not for any aspirations of fame or fortune. More than anything, through my work, I simply hope to stimulate self-reflection and thought provoking conversations. And I hope I’ve done that with this book, as well as the subsequent discussions I’ve had in interviews, articles, podcasts, and other media forums.

Another fun activity around the launch was my Bit Flip Virtual Book Tour—a series of over twenty short videos posted on my YouTube channel in which I explore different real-world locations that have cameos in the book. Although shooting these with my tripod and iPhone garnered plenty of curious onlookers, they have, to my astonishment, collectively garnered over 75,000 views—or about one view per person-year of time I put into producing them. So check them out.

My other observation a year later is I feel like I’m finally just now starting to get in the groove of being an author—and the constant context switches this vocation demands. Publishing any book requires three main phases of effort: writing the book, editing the book, and promoting the book. I currently have a novel in each of those three phases. I’m still promoting Bit Flip while I’m in the final editing stages of my second novel, Burner, and I'm busy writing my third novel, Outage. The baton pass of each of these projects will happen nearly in tandem. With this one-year milestone, the promotional efforts on Bit Flip will wind down, and I’ll shift my promotional focus to Burner, which comes out April 16, 2024. At the same time, as Outage moves into the editing phase, I’ll begin writing my next novel.

Doing this for the first time, I have a newfound respect for authors who crank out a book a year and have ten, twenty, thirty or more books to their name. It’s a never-ending cycle, requiring very different brain power—from the uninterrupted flow-state of writing, to the meticulous attention to detail of editing, to the tireless whirlwind of activity of promotion. But I’ve found I enjoy each phase for different reasons—in part, precisely because each exercises different parts of my brain. I feel very fortunate to have found such a gratifying new career at this stage in my life, and I strive to continuously improve as an author.

So happy birthday to what will always be my first literary baby. And thank you all again for your support.

July 31, 2023

Tech as the Battlefield

An AI-generated image of a technology battlefield.

The technology industry and the defense industry have always shared an intimately close relationship. Most technology sectors, from semiconductors to the internet, originated from massive investment by the U.S. Federal Government. And America’s technological superiority has been decisive in establishing our military dominance—from better combat communications to more accurate missiles.

But today with the rapid rise of AI, we seem to be headed into an era in which these industries are more than just inter-related. Technology is becoming the primary military battlefield on which modern geopolitical conflicts will be fought. That emerging reality has drawn comparisons to the race to develop atomic weapons during World War II, with Alexander Karp, the CEO of defense intelligence analytics company Palantir, declaring the creation of AI weapons our “Oppenheimer Moment” in a recent op-ed in The New York Times.

Although much of the piece is delivered in tiresome, anti-woke rhetoric (e.g. “The preoccupations and political instincts of coastal elites may be essential to maintaining their sense of self and cultural superiority but do little to advance the interests of our republic.”), the core of Karp’s argument highlights the dilemma the United States is facing: specifically that, “Our adversaries will not pause to indulge in theatrical debates about the merits of developing technologies with critical military and national security applications. They will proceed. This is an arms race of a different kind, and it has begun.”

Written in response to the public letter signed by many industry experts warning AI presents a “risk of extinction” and a recent White House event at which top AI companies committed to safeguards around the technology, Karp is espousing a distinctly conservative philosophy—that escalation is the best form of deterrence; that not only developing but being willing to use next-generation weaponry will somehow ensure our safety. It is the argument one would expect from a purveyor of such weapons, analogous to gun manufacturers calling for more guns to defend ourselves from gun violence.

While such a “if-we-don’t-do-it-our-enemies-will” philosophy severely blurs the line between defender and aggressor, the argument certainly has historical precedence. The primary rationalization for one of the most horrific acts of war of all time—indiscriminately killing an estimated 200,000 Japanese civilians nearly instantly in Hiroshima and Nagasaki—was that it abruptly ended the war in the Pacific and ushered in a prolonged era of peace, albeit one defined by a decades-long cold war, devastating regional conflicts, and the continuous escalation of a nuclear arms race. Regardless, the one—and, thankfully for humanity thus far, only—decision to use nuclear weapons was made in the midst of the deadliest armed conflict in human history in which over 60 million people were killed. The possibility that nuclear weapons would destroy humanity seemed a gamble worth taking when humanity seemed to be already on that course.

To be clear, we are not in the midst of such a conflict.

In fact, the decision to deploy AI technology for lethal military purposes seems, at best, unnecessary, and, at worst, apocalyptic. It was the expense and expertise required to develop nuclear weapons, controlled by governments and military officials acutely aware of the likelihood of mutually assured destruction, that constrained most military conflicts over the last 80 years to conventional warfare. Human beings, with our innate tendencies toward self-preservation, empathy toward other human beings, and a general mooring of ethics, have decided not to deploy nuclear weapons. Even the most despotic leaders have resisted their use. An untethered AI algorithm would not be constrained by a guilty conscience or its own mortality. The purpose and promise of AI is to leverage data to learn autonomously how to achieve an objective with increasing efficiency. Without the inconvenient constraints placed on it by humans, AI can notoriously devise suboptimal solutions. Indeed, AI seems less likely to end a war than to start one.

Another reason history seems unlikely to repeat itself in the race to weaponize AI is the role of corporations in its development. Rather than one government-funded Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, there are hundreds of venture-funded AI companies in Palo Alto and around the world. While we might quibble over the corporate structure, companies like Huawei and Palantir are both mechanisms for advancing the strategic aims of their respective countries, while making their founders and executives fabulously rich. Palantir made Karp a billionaire, just like Palantir co-founder and lead investor, Peter Thiel. Such private sector financial incentives make it exceedingly difficult to put the cat back in the bag. While we debate the ethics of AI or even enact regulatory policies, there’s always going to be a new company in another country with eager investors that is unbound by such ethical dilemmas.

This rapidly escalating battle for technological dominance will almost certainly be the defining geopolitical confrontation of our time. As the technological skirmishes and subterfuge continue, one thing is certain: it makes for great storytelling. Just as Nazi Germany during WWII, the cold war against the Soviet Union, and the so-called “war on terror” in the Middle East have been the basis of innumerable novels, movies, and TV shows, AI is emerging as the next super villain. It has all the traits of a perfect antagonist: something ubiquitous and familiar, designed with the best intentions, but that is going awry due to nefarious and unseen actors, spiraling out of our control and turning against us to threaten the existence of our species and the planet as a whole.

My third novel which I am currently writing (working title Outage), is about just such a premise. In the story, a state-sponsored AI algorithm learns to exploit vulnerabilities in communications chips to disable all internet and mobile phone communications in the U.S., told from the perspective of one family in suburban Virginia. This book continues my macro theme in all my work of exploring how technology is shaping our lives, not always for the better. Storytelling is frequently a forum for expressing, sharing, and analyzing our deepest fears. And given the speed and uncertainty with which AI is evolving, it is sure to be the subject of many more stories for a long time.

June 30, 2023

Burner Cover Reveal

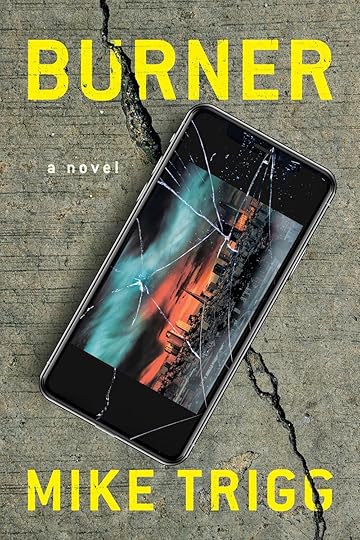

I’m so excited to share this advance preview of the cover design for my upcoming second novel, Burner, with you—my site subscribers. Designed by Julie Metz and the team at SparkPress, the cover perfectly communicates so much of what the novel is about—a twisty contemporary thriller, set in San Francisco, that delivers an edge-of-your seat, chaotic ride from start to finish.

With the cracked phone dropped on the pavement, the design captures the opening of the novel when a massive protest in downtown San Francisco spirals out of control. It also conveys the many meanings of the title. “Burner” refers most obviously to a burner phone—cheap, disposable, and, most of all, anonymous. But “Burner” also refers to the username Burner_911, the anonymous leader of a massive populist movement and antagonistic force throughout the story. And “Burner” is also a mindset—an ego-centric, scorched-earth mentality of wanting to burn everything down, born from the toxic blend of vanity, greed, and disenfranchisement that is so pervasive in many online communities.

The cover for my next novel, Burner. Coming April 16, 2024 (SparkPress).

Inspired by the explosive events of our polarized political climate, Burner is an all-too plausible contemporary thriller that examines the social and personal consequences of the lost sense of identity, trust, and truth itself that characterizes our technology-obsessed culture.

Shane Stoller has just been arrested for domestic terrorism, accused of being the mastermind behind the online profile Burner_911, the anonymous leader of a massive populist movement. Chloe Corbin has just been abducted by Burner_911’s followers in a lawless uprising on the streets of San Francisco, targeted as the socialite daughter of a tech billionaire. What nobody knows is that Shane and Chloe are secretly in love despite coming from opposite worlds. Plagued with regret but unable to communicate with his followers from prison, Shane tries desperately to find a way to save Chloe from the forces he has unleashed. From her own captivity, Chloe becomes more sympathetic to Burner_911’s cause, and transitions from victim to conspirator in an effort to free herself and exonerate Shane.

Part tragic love story, part mind-bending psychological thriller, Burner dives headfirst into the modern zeitgeist of politically motivated disinformation, toxic internet subcultures, and our continuing need for belonging, purpose, and love in an age of distorted online personas.

June 12, 2023

Wrapping Up ThrillerFest 2023

Hanging with one of my favorite authors and overall great guy, Shawn Cosby. His latest novel, All the Sinners Bleed, just came out on June 6, 2023.

For the second year in a row, I kicked off the month of June with a visit to New York City for ThrillerFest. Hosted by the International Thriller Writers organization and now in its eighteenth year, ThrillerFest is the premier conference for authors, agents, publishers, and fans of the thriller literary genre. If you fit one of those descriptions, I can't recommend the conference enough.

Taking place over five days in the heart of New York City, ThrillerFest is truly unique among writing conferences. After attending the conference for the first time last year, I got much more deeply involved in this year’s event—including as a volunteer staffer, a judge in the best e-book category, and a speaker on a panel moderated by the legendary author, Heather Graham.

I got so much out of the conference this year that I found myself contemplating what makes ThrillerFest so special. Three qualities really set this conference apart:

Relevance—By focusing specifically on thriller, mystery, and suspense, the sessions are highly focused on improving your craft in that genre. Topics include everything from FBI procedures to plot twists, psychological profiling to character development, with experts in every area imaginable for thriller writing.

Collaboration—Every attendee brings the mindset that they have both something to learn and to teach. I sat in on panels with authors who later sat in on my panel. Through ThrillerFest, I have joined a critique group that has dramatically improved the quality of my writing through collaborative critiques of each others’ work.

Community—Perhaps most of all, ThrillerFest is an incredibly supportive community. Bestselling authors not only attend but are involved and accessible, even to the newest aspiring authors. Agents and publishers are eager to meet new talent in both formal pitches and informal receptions. There is no sharp-elbowed competition or one-upmanship. Everyone genuinely wants to see each other succeed, and those successes are celebrated with an awards banquet to conclude the conference.

Front row for a talk by former FBI Director James Comey.

I truly feel that I have “found my people” with respect to a writing community through ThrillerFest. From honing your craft in hands-on workshops, to deepening your domain expertise with incredible speakers, to pitching leading agents, ThrillerFest offers myriad ways to make you a better writer—and form supportive new friendships along the way—regardless of where you are in the author journey.

Huge thank you to all the organizers, volunteers, and everyone else who make this conference such a success. I can’t wait for next year!

An all-star ThrillerFest panel with (L to R) Charlaine Harris, Michael Connelley, Lisa Gardner, Jack Carr, Mark Greaney, and Brad Thor. (Host: Isabella Maldonado)