Adam Thierer's Blog, page 89

July 19, 2012

Video: How I Think about Privacy

Last month, it was my great privilege to be invited to deliver some remarks at the University of Maine’s Center for Law and Innovation (CLI) as part of their annual “Privacy in Practice” conference. Rita Heimes and Andrew Clearwater of the CLI put together a terrific program that also featured privacy gurus Harriet Pearson, Chris Wolf, Omer Tene, Kris Klein and Trevor Hughes. [Click on their names to watch their presentations.] In my remarks, I presented a wide-ranging (sometimes rambling) overview of how privacy policy is unfolding here in the U.S. as compared to the European Union, and also offered a full-throated defense of America’s approach to privacy as compared to the model from the other side of the Atlantic that many now want us to adopt here in the U.S. I also identified the many interesting parallels between online child safety policy and privacy policy here in the U.S. and discussed how we can apply a similar toolbox of solutions to problems that arise in both contexts. If you’re interested, I’ve embedded my entire 20-minute speech below, but I encourage you to also check out the other speakers videos that the folks at the CLI have posted on their site here. And keep an eye on the Maine Center for Law and Innovation; it is an up and coming powerhouse in the field of cyberlaw and Internet policy.

July 16, 2012

Christopher Sprigman on the Knockoff Economy

Christopher Sprigman, professor of law at the University of Virginia discusses his upcoming book the Knockoff Economy: How Imitation sparks Innovation co authored with Kal Raustiala. The book is an accessible look at how industries that do not have heavily enforced copyright law, such as the fashion and culinary industries, are still thriving and innovative. Sprigman explains how copyright was not able to be litigated heavily in these cases and what the results could teach us about what other industries that do have extensive copyright enforcement, such as the music and movie industries, could look like without it.

“The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation”, Sprigman and Raustiala

“The Piracy Paradox: Innovation and Intellectual Property in Fashion Design”, by Sprigman and Raustiala

“Standup comedy and the rise of an informal intellectual property regime”, Bloomberg BNA

“Why There Are Too Many Patents in America”, Posner Article

Waiting for the Next Fred Kahn

It is unlikely there has ever been a more important figure in the history of regulatory policy than Alfred Kahn. As I noted in this appreciation upon his passing in December 2010, his achievements as both an academic and an policymaker in this arena where monumental. His life was the very embodiment of the phrase “ideas have consequences.” His ideas changed the world profoundly and all consumers owe him a massive debt of gratitude for reversing the anti-consumer regulatory policies that stifled competition, choice, and innovation. It was also my profound pleasure to get to know Fred personally over the last two decades of his life and to enjoy his spectacular wit and unparalleled charm. He was the most gracious and entertaining intellectual I have ever interacted with and I miss him dearly.

It is unlikely there has ever been a more important figure in the history of regulatory policy than Alfred Kahn. As I noted in this appreciation upon his passing in December 2010, his achievements as both an academic and an policymaker in this arena where monumental. His life was the very embodiment of the phrase “ideas have consequences.” His ideas changed the world profoundly and all consumers owe him a massive debt of gratitude for reversing the anti-consumer regulatory policies that stifled competition, choice, and innovation. It was also my profound pleasure to get to know Fred personally over the last two decades of his life and to enjoy his spectacular wit and unparalleled charm. He was the most gracious and entertaining intellectual I have ever interacted with and I miss him dearly.

As I noted in my earlier appreciation, Fred was a self-described “good liberal Democrat” who was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to serve as Chairman of the Civil Aeronautics Board in the mid-1970s and promptly set to work with other liberals, such as Sen. Ted Kennedy, Stephen Breyer, and Ralph Nader, to dismantle anti-consumer airline cartels that had been sustained by government regulation. These men achieved a veritable public policy revolution in just a few short years. Not only did they comprehensively deregulate airline markets but they also got rid of the entire regulatory agency in the process. Folks, that is how you end crony capitalism once and for all!

Who could imagine such a thing happening today? It’s getting hard for me to believe it could. The cronyist cesspool of entrenched Washington special interests don’t want it. Neither do the regulators, of course. Nor do any Democrats or Republicans on the Hill. And all those self-anointed “consumer advocates” running around D.C. scream bloody murder at the very thought. All these people are happy with the regulatory status quo because it guarantees them power and influence–even if it screws consumers and stifles innovation in the process.

And so, when I reach my most pessimistic depths of despair like this, I go back and read Fred. I remember what one man accomplished through the power of ideas and I hope to myself that there’s another Fred out there ready to come to Beltway, shake things up, and start clearing out the morass of anti-consumer, anti-innovation regulations that pervade so many fields–but especially communications and technology.

I could cite endless wisdom from his 2-volume masterwork, The Economics of Regulation, but instead I will encourage you to pick that up if it’s not already on your shelf. It will forever change the way you think about economic regulation. Instead, I will leave you with a few things from Fred that you might not have seen before since they appeared in two obscure speeches delivered just a year apart to the American Bar Association. Just imagine being in the crowd when a sitting regulator delivered these remarks to a bunch of bureaucrats, regulatory lawyers, and industry fat cats. Oh my, how they must have all cringed!

Remarks before the American Bar Association, New York, August 8, 1978:

I believe that one substantive regulatory principle on which we can all agree is the principle of minimizing coercion: that when the government presumes to interfere with peoples’ freedom of action, it should bear a heavy burden of proof that the restriction is genuinely necessary…

Remarks before the American Bar Association, Dallas, TX, August 15, 1979:

I think it unquestionable that there is a basic difference between the regulatory mentality and the philosophical approach of relying on the competitive market to restrain people. The regulator has a very high propensity to meddle; the advocate of competition, to keep his hands off. The regulator prefers order; competition is disorderly. The regulator prefers predictability and reliability; competition has the virtue as well as the defect that its results are unpredictable. Indeed, it is precisely because of the inability of any individual, cartel or government agency to predict tomorrow’s technology or market opportunities that we have a general preference for leaving the outcome to the decentralized market process, in which the probing of these opportunities is left to diffused private profit-seeking.

The regulator prefers instead to rely on selected chosen instruments, whom he offers protection from competition in exchange for the obligation to serve, as well as, often, transferring income from one group of customers to another — that is, using the sheltered, monopoly profits from the lucrative part of the business to subsidize the provision of service to other, worthy groups of customers. No matter that the social obligations are often ill-defined, and sometimes not defined or enforced at all; the protectionist bias of regulation is unmistakable.

July 15, 2012

Journalists, Technopanics & the Risk Response Continuum

I hope everyone caught these recent articles by two of my favorite journalists, Kashmir Hill (“Do We Overestimate The Internet’s Danger For Kids?”) and Larry Magid (“Putting Techno-Panics into Perspective.”) In these and other essays, Hill and Magid do a nice job discussing how society responds to new Internet risks while also explaining how those risks are often blown out of proportion to begin with.

Both Hill and Magid are rarities among technology journalists in that they spend more time debunking fears rather than inflating them. Whether its online safety, cybersecurity, or digital privacy, we all too often see journalists distorting or ignoring how humans find constructive ways to cope with technological change. Why do journalists fail to make that point? I suppose it is because bad news sells–even when there isn’t much to substantiate it.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about “moral panics” and “technopanics” in recent years (here’s a compendium of roughly two dozen essays I’ve penned on the topic) and earlier this year I brought all my work together in an 80-page paper entitled, “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle.”

In that paper, I identified several reasons why pessimistic, fear-mongering attitudes often dominate discussions about the Internet and information technology. I began by noting that the biggest problem is that for a variety of reasons, humans are poor judges of risks to themselves or those close to them. But I identified other explanations for why human beings are predisposed toward pessimism and are risk-averse, including:

Generational Differences

Hyper-Nostalgia, Pessimistic Bias, and Soft Ludditism

Bad News Sells: The Role of the Media, Advocates, and the Listener

The Role of Special Interests and Industry Infighting

Elitist Attitudes among Academics and Intellectuals

The Role of “Third-Person-Effect Hypothesis”

You can read my paper for fuller descriptions of each point. But let me return to my primary concern here regarding the role that the media plays in the process. It seems logical why journalists inflate fears: In an increasingly crowded and cacophonous modern media environment, there’s a strong incentive for them to use fear to grab attention. But why are we, the public, such eager listeners and so willing to lap up bad news, even when it is overhyped, exaggerated, or misreported?

“Negativity bias” certainly must be part of the answer. Michael Shermer, author of The Believing Brain, notes that psychologists have identified “negativity bias” as “the tendency to pay closer attention and give more weight to negative events, beliefs, and information than to positive.” Negativity bias, which is closely related to the phenomenon of “pessimistic bias,” is frequently on display in debates over online child safety, digital privacy, and cybersecurity.

But even with negativity bias at work, what I still cannot explain is why so many of these inflated fears exists when we have centuries of experience and empirical results that prove humans are able to again and again adapt to technological change. We are highly resilient, adaptable mammals. We learn to cope.

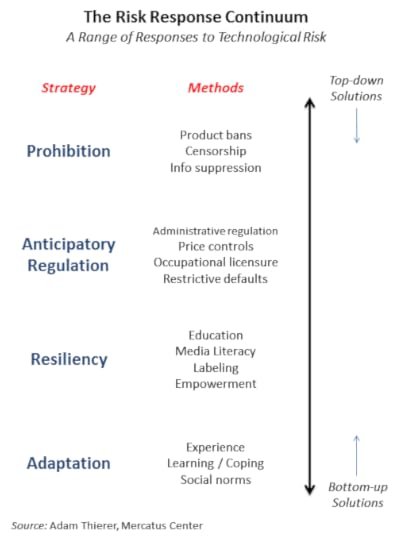

In my paper, I try to develop a model for how humans deal with new technological risks. I identify four general groups of responses and place them along a “risk response continuum”:

Prohibition: Prohibition attempts to eliminate potential risk through suppression of technology, product or service bans, information controls, or outright censorship.

Anticipatory Regulation: Anticipatory regulation controls potential risk through preemptive, precautionary safeguards, including administrative regulation, government ownership or licensing controls, or restrictive defaults. Anticipatory regulation can lead to prohibition, although that tends to be rare, at least in the United States.

Resiliency: Resiliency addresses risk through education, awareness building, transparency and labeling, and empowerment steps and tools.

Adaptation: Adaptation involves learning to live with risk through trial-and-error experimentation, experience, coping mechanisms, and social norms. Adaptation strategies often begin with, or evolve out of, resiliency-based efforts.

For reasons I outline in the paper, I believe that it almost always makes more sense to use bottom-up resiliency and adaptation solutions instead of top-down anticipatory regulation or prohibition strategies. And, more often than not, that’s what we eventually opt for as a society, at least when it comes to information technology. Sure, you can find plenty of examples of knee-jerk prohibition and regulatory strategies being proposed initially as a response to an emerging technology. In the long-run, however–and sometimes even in the short-run–we usually migrate down the risk response continuum and settle into resiliency and adaptation solutions. Sometimes we adopt those approaches because we come to understand they are more sensible or less costly. Other times we get there only after several failed experiments with prohibition and regulation strategies.

I know I am being a bit too black and white here. Sometimes we utilize hybrid approaches–a bit of anticipatory regulation with a bit of resiliency, for example. We use such an approach for both privacy and security matters, for example. But I have argued in my work that the sheer velocity of change in the information age makes it less and less likely that anticipatory regulation strategies–and certainly prohibition strategies–will work in the long-haul. In fact, they often break down very rapidly, making it all the more essential that we begin thinking seriously about resiliency strategies as soon as we are confronted with new technological risks. Adaptation isn’t usually the correct strategy right out of the gates, however. Just saying “learn to to live with it” or “get over it” won’t work as a short-term strategy, even if that’s exactly what will happen over the long-term. But resiliency strategies often help us get to adaption strategies and solutions more quickly.

Anyway, back to journalists and fear. It strikes me that sharp journalists like Hill and Magid just seem to get everything I’m saying here and they weave these insights into all their reporting. By why do so few others? Again, I suppose it is because the incentives are screwy here and make it so that even those reporters who know better will sometimes use fear-based tactics to sell copy. But I am still surprised by how often even respected mainstream media establishments play this game.

In any event, those others reporters need to learn to give humans a bit more credit and acknowledge that (a) we often learn to cope with technological risks quite rapidly and (b) sometimes those risks are greatly inflated to begin with.

July 14, 2012

Video: Competition & Innovation in the Digital Economy

Is competition really a problem in the tech industry? That was the question the folks over at WebProNews asked me to come on their show and discuss this week. I offer my thoughts in the following 15-minute clip. Also, down below I have embedded a few of my recent relevant essays on this topic, a few of which I mentioned during the show.

“On Fast Firms, Slow Regulators, Antitrust & the Digital Economy,” Technology Liberation Front, July 6, 2012

“The Rule Of Three: The Nature of Competition In The Digital Economy,” Forbes, June 29, 2012.

“Sunsetting Technology Regulation: Applying Moore’s Law to Washington,” Forbes, May 25, 2012.

“Of “Tech Titans” and Schumpeter’s Vision,” Forbes, August 22, 2011.

“Bye Bye BlackBerry. How Long Will Apple Last?” Forbes, April 1, 2012.

“Gary Reback’s Antitrust Love Letter,” Technology Liberation Front, September 20, 2009.

“What is “Optimal Interoperability”? A Review of Palfrey & Gasser’s’“Interop,’” Technology Liberation Front, June 11, 2012.

July 13, 2012

DoJ Chokes Wireless Broadband to “Save” Wireline

It’s come to this. After more than a decade of policies aimed at reducing the telephone companies’ share of the landline broadband market, the feds now want to thwart a key wireless deal on the remote chance it might result in a major phone company exiting the wireline market completely.

The Department of Justice is holding up the $3.9 billion deal that would transfer a block of unused wireless spectrum from a consortium of four cable companies to Verizon Wireless, an arm of Verizon, the country’s largest phone company.

The rationale, reports The Washington Post’s Cecilia Kang, is that DoJ is concerned the deal, which also would involve a wireless co-marketing agreement with Comcast, Cox, Time Warner and Bright House Networks, the companies that jointly own the spectrum in question, would lead Verizon to neglect of its FiOS fiber-to-the-home service.

There’s no evidence that this might happen, but the fact that DoJ put it on the table demonstrates the problems inherent in government attempts to regulate competition.

For years, broadband competition has been an obsession at a number of agencies, starting with the FCC but also addressed by DoJ, the Federal Trade Commission, Congress and the White House. Federal policies such as UNE-P, network neutrality, spectrum set-asides and universal service funding have all sought to artificially tilt the competitive advantage toward non-incumbent providers, regardless of their overall financial viability (think Solyndra). State and local officials took the cue, and state public utilities commissions developed their own UNE-P-type set-ups and endorsed fiscally suicidal municipal broadband projects, all aimed at providing competitive alternatives to “monopolistic” telephone company broadband service.

So there’s some regulatory whiplash when a major government agency says that a competitively weak Verizon would be bad for consumers.

Nonetheless, this is pure supposition. Verizon shows every sign of remaining a significant competitor. The company is upgrading its FiOS service, offering speeds of up to 300 Mb/s. The Newark Star-Ledger, citing data from the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities, in June reported that cable companies are losing subscribers to FiOS, in the Garden State and the nation. “Verizon FiOS ate up market share in Jersey and the nation, growing nearly 20 percent through 2011 in Jersey, even better than the national gain for paid TV by telecommunications companies, up 15 percent,” the Ledger states.

Balanced against DoJ’s academic speculation is the fact that the cable spectrum is sitting unused amid a dire spectrum crunch. Wireless demand is booming, yet the government’s penchant for precautionary regulation is getting in the way of market-based solutions to real-world problems.

Moreover, as Scott Cleland points out on his blog, the Verizon-cable deal will create more competition as it will allow the four cable companies to bundle wireless service with cable. “The Verizon-Cable spectrum transaction, as currently configured,” Cleland writes, “is now a series of integrated secondary market transactions that result in multiple competitors gaining access to spectrum that they need, which will enable them to offer faster and more competitive broadband offerings, greatly benefiting American consumers.”

Even President Obama’s notoriously activist FCC cleared the spectrum sale, stipulating only that Verizon swap some of the acquired spectrum with T-Mobile (perhaps to abate some of the consequences of the FCC’s competition-obsessed decision to kill T-Mobile’s merger with AT&T, a rant for another day). But that condition itself implied an understanding that getting additional spectrum in play is a paramount goal.

July 12, 2012

DirecTV’s Viacom Gambit

I suppose there’s something to be said for the fact that two days into DirecTV’s shutdown of 17 Viacom programming channels (26 if you count the HD feeds) no congressman, senator or FCC chairman has come forth demanding that DirecTV reinstate them to protect consumers’ “right” to watch SpongeBob SquarePants.

I suppose there’s something to be said for the fact that two days into DirecTV’s shutdown of 17 Viacom programming channels (26 if you count the HD feeds) no congressman, senator or FCC chairman has come forth demanding that DirecTV reinstate them to protect consumers’ “right” to watch SpongeBob SquarePants.

Yes, it’s another one of those dust-ups between studios and cable/satellite companies over the cost of carrying programming. Two weeks ago, DirecTV competitor Dish Network dropped AMC, IFC and WE TV. As with AMC and Dish, Viacom wants a bigger payment—in this case 30 percent more—from DirecTV to carry its channel line-up, which includes Comedy Central, MTV and Nickelodeon. DirecTV, balked, wanting to keep its own prices down. Hence, as of yesterday, those channels are not available pending a resolution.

As I have said in the past, Washington should let both these disputes play out. For starters, despite some consumer complaints, demographics might be in DirecTV’s favor. True, Viacom has some popular channels with popular shows. But they all skew to younger age groups that are turning to their tablets and smartphones for viewing entertainment. At the same time, satellite TV service likely skews toward homeowners, a slightly older demographic. It could be that DirecTV’s research and the math shows dropping Viacom will not cost them too many subscribers.

This is the new reality of TV viewing. If you are willing to wait a few days, you can download most of Comedy Central’s latest episodes for free (although John Bergmayer at Public Knowledge reports that, in a move related to the DirecTV dispute, Comedy Central has pulled The Daily Show episodes from its site, although they are still available at Hulu).

What’s more, in a decision that should raise eyebrows all around, AMC said it will allow Dish subscribers to watch the season premiere of its hit series Breaking Bad online this Sunday, simultaneous with the broadcast/cablecast. This decision should be the final coffin nail for the regulatory claim of “cable programming bottleneck.” Obviously, studios have other means of reaching their audience, and are willing to use them when they have to.

Meanwhile, a Michigan user, commenting on the DirecTV-Viacom fight, told the MLive web site that “I love [DirecTV] compared to everyone else. I get local channels, I get sports channels. I wouldn’t have chosen if it was a problem.”

Now if Congress or the FCC steps up and requires that satellite and cable companies carry programming on behalf of Hollywood, the irony would be rich. Recall that just a few years ago, Congress and the FCC were pushing for a la carte regulation that would require cable companies to reduce total channel packaging and let consumers essentially pick the ones they want. Even the Parents Television Council is glomming onto this, as reported in the Washington Post, although not precisely from a libertarian perspective.

“The contract negotiation between DirecTV and Viacom is the latest startling example of failure in the marketplace through forced product bundling,” said PTC President Tim Winter in a statement calling on Congress and the FCC to examine the issue. “The easy answer is to allow consumers to pick and pay for the cable channels they want,” he said.

Winter’s mistake is that he views DirecTV’s challenge to Viacom as marketplace failure. Quite the contrary, it is a sure sign of a functional marketplace when one party feels it has the leverage to say no to a supplier’s aggressive price increase. And while I would be against a ruling forcing cable and satellite companies to construct a la carte alternatives, market evolution may soon be taking us there, but perhaps not the way activists imagined.

I’ll hazard a guess to say that today’s viewer paradigm isn’t so much “I never watch such-and-such a channel” than “I only watch one show on such-and-such a channel.” When Dish cuts off AMC and DirecTV cuts off Comedy Channel et al, they are banking that their customers won’t miss the station, just a handful of shows that they will be motivated enough to find elsewhere, if they haven’t done so already.

It might take a pencil and paper, but there is enough price transparency for a budget-minded video consumer to calculate the best balance between multichannel TV program platforms like satellite and cable, pay-per-view video, free and paid digital downloads and DVD rentals. The cable cord (or satellite link) may be difficult to cut completely, but the $200-a-month bill packed with multiple premium channel packages is endangered. The video consumer of the near-future might still keep cable or satellite for ESPN for Monday Night Football, but turn to Netflix for Game of Thrones, iTunes for Breaking Bad, and the bargain DVD bin for a season box set of Dora the Explorer videos. DirecTV and Dish Network are confronting these economics by confronting studios on their distribution strategy. The studios, for their part, may find they can’t aggressively exploit other digital channels and keep raising rates for multichannel operators.

While disputes like this are messy for consumers in the short term, the resolution will be a consumer win because it will force multichannel operators and the studios to adapt to actual changes in consumer behavior, not a policymaker’s construct of competitive supply chain. Washington would be wise to stay out.

July 11, 2012

Eli Dourado on fighting malware without laws

Eli Dourado, a research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, discusses malware and possible ways to deal with it. Dourado notes several shortcomings of a government response including the fact that the people who create malware come from many different countries some of which would not be compliant with the US or other countries seeking to punish a malware author. Introducing indirect liability for ISPs whose users spread malware, as some suggest, is not necessary, according to Dourado. Service providers have already developed informal institutions on the Internet to deal with the problem. These real informal systems are more efficient than a hypothetical liability regime, Dourado argues.

Related Links

“Internet Security Without Law: How Service Providers Create Online Order”, Eli Dourado

“Holding Internet Service Providers Accountable”, Posner and Lichtman Paper

“Spam Volumes Drop by Two-Thirds After Firm Goes Offline, Washington Post

Coase Theorum

July 9, 2012

Still Seeking Advantageous Regulation in Telecom

One of the most egregious examples of special interest pleading before the Federal Communications Commission and now possibly before Congress involves the pricing of “special access,” a private line service that high-volume customers purchase from telecommunications providers such as AT&T and Verizon. Sprint, for example, purchases these services to connect its cell towers.

Sprint has been seeking government-mandated discounts in the prices charged by AT&T, Verizon and other incumbent local exchange carriers for years. Although Sprint has failed to

make a remotely plausible case for re-regulation, fuzzy-headed policymakers are considering using taxpayer’s money in an attempt to gather potentially useless data on Sprint’s behalf.

Sprint is trying to undo a regulatory policy adopted by the FCC during the Clinton era. The commission ordered pricing flexibility for special access in 1999 as a result of massive investment in fiber optic networks. Price caps, the commission explained, were designed to act as a “transitional regulatory scheme until actual competition makes price cap regulation

unnecessary.” The commission rejected proposals to grant pricing flexibility in geographic areas smaller than Metropolitan Statistical Areas, noting that

because regulation is not an exact science, we cannot time the grant of regulatory relief to coincide precisely with the advent of competitive alternatives for access to each individual end user. We conclude that the costs of delaying regulatory relief outweigh the potential costs of granting it before [interexchange carriers] have a competitive alternative for each and every end user. The Commission has determined on several occasions that retaining regulations longer than necessary is contrary to the public interest. Almost 20 years ago, the Commission determined that regulation imposes costs on common carriers and the public, and that a regulation should be eliminated when its costs outweigh its benefits. (footnotes omitted.)

Though many of the firms that were laying fiber during that period subsequently went bankrupt, the fiber is still in place. According to the 1999 commission,

If a competitive LEC has made a substantial sunk investment in equipment, that equipment remains available and capable of providing service in competition with the incumbent, even if the incumbent succeeds in driving that competitor from the market. Another firm can buy the facilities at a price that reflects expected future earnings and, as long as it can charge a price that covers average variable cost, will be able to compete with the incumbent LEC. In telecommunications, where variable costs are a small fraction of total costs, the presence of facilities-based competition with significant sunk investment makes exclusionary pricing behavior costly and highly unlikely to succeed. (footnotes omitted.)

Although many of the cell towers that require special access services today did not exist in 1999, investment in new fiber has resumed. Citing research firm CRU Group, the Wall Street Journal reported in April that

Some 19 million miles of optical fiber were installed in the U.S. last year, the most since the boom year of 2000. Corning Inc., a leading maker of fiber, sold record volumes last year and is telling new customers that it can’t guarantee their orders will be filled. (references omitted.)

Sprint nevertheless argues that “[r]easonably priced and broadly available private line services are particularly important for wireless carriers who depend on affordable backhaul to offer their wireless services,” and alleges that incumbent providers charge “supra-competitive rates” and “impose unreasonable and anti-competitive service terms that many purchasers of private line services are forced to accept because in many areas there are insufficient competitive alternatives.”

The last time someone looked carefully at this was early 2009, when Peter Bluhm and Dr. Robert Loube examined whether it was true that AT&T, Qwest (now CenturyLink) and Verizon were earning 138%, 175% and 62%, respectively, on the special access services they provided, as specialized accounting reports maintained by the FCC implied. In the report that Bluhm and Loube prepared for the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC), they concluded that these figures were virtually meaningless and that the actual returns were more likely in the range of 30%, 38% and 15%, respectively.

These rates are higher than the 11.25% rate of return that telephone companies were entitled to earn when they were fully regulated. On the other hand, the authorized rate of return was an average that concealed tremendous cost shifting from residential to business subscribers and from local to long distance. Therefore, it is doubtful whether Sprint could have expected to purchase special access

services for no more than 11.25% above cost even during the old days of fully regulated telecom markets.

Speaking of those days – celebrated by some as a golden era when regulators “protected” consumers – it is worth remembering that there was a dark side to telecom regulation, as Reed E. Hundt, chairman of the FCC when Congress passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996, referenced in his book (You Say You Want a Revolution: A Story of Information Age Politics, 2000).

Behind the existing rules, however, were two unwritten principles. First, by separating industries through regulation, government provided a balance of power in which each industry could be set against one another in order for elected figures to raise money from the different camps that sought advantageous regulation. Second, by protecting monopolies, the Commission could essentially guarantee that no communications business would fail. Repealing these implicit rules was a far less facile affair than promoting competition.

Sadly, this sort of thing is still alive and well. Re-regulating special access pricing is one of the issues that may emerge at Tuesday’s FCC oversight hearing in the Subcommittee on Communications and Technology, and the FCC is reported to be working on an order that would require collection of additional data to evaluate the current regime, according

to a majority committee staff background memo.

Based on the available evidence, Sprint appears to be looking for a handout. The facts don’t justify re-regulation. Why should taxpayers pay for gathering evidence that may or may not support a corporation’s plea for advantageous regulation?

Policymakers have much better things to do than entertain this vacuous debate. If, as Sprint alleges, it is profitable for AT&T and Verizon to provide special access services, competitors will provide them, too, and competition will discipline prices. If the current prices are not unreasonable, re-regulation will discourage private investment and diminish competition.

July 6, 2012

On Fast Firms, Slow Regulators, Antitrust & the Digital Economy

I liked the title of this new Cecilia Kang article in the Washington Post: “In Silicon Valley, Fast Firms and Slow Regulators.” Kang notes:

As federal regulators launch fresh investigations into Silicon Valley, their history of drawn-out cases has companies on edge. In taking on an industry that moves at lightening speed, federal officials risk actions that could appear to be too heavy-handed or embarrassingly outdated, some analysts and antitrust experts say.

For example, she cites ongoing regulatory oversight of Microsoft and MySpace, even though both companies have fallen from the earlier King of the Hill status in their respective fields. Kang notes that some “want the government to aggressively pursue abusive practices but question whether antitrust laws are too dated to rein in firms that are continually redefining themselves and using their dominance in one arena to press into others.”

Simply put, antitrust can’t keep up with an economy built on Moore’s Law, which refers to the rule of thumb that the processing power of computers doubles roughly every 18 months while prices remain fairly constant. This issue has been the topic of several of my Forbes columns over the past year, as well as several other essays I’ve written here and elsewhere. [See the list at bottom of this essay.] Moore’s Law has been a relentless regulator of markets and has helped keep the power of “tech titans” in check better than any Beltway regulator ever could. As I noted here before in my essay, “Antitrust & Innovation in the New Economy: The Problem with the Static Equilibrium Mindset“:

modern tech markets are highly dynamic. There is no static end-state, “perfect competition,” or “market equilibrium” in today’s information technology marketplace. Change and innovation are chaotic, non-linear, and paradigm-shattering. Schumpeter said it best long ago when he noted how, “in capitalist reality as distinguished from its textbook picture, it is not [perfect] competition which counts but the competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization… competition which commands a decisive cost or quality advantage and which strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives. This kind of competition is as much more effective than the other,” he argued, because the “ever-present threat” of dynamic, disruptive change “disciplines before it attacks.”

Once we recognize the power of Moore’s Law to naturally regulate markets—and the corresponding danger of leaving Washington’s laws on the books too long—it should be clear why it is essential to align America’s legal and regulatory policies with the realities of modern tech markets. One way policymakers could do so, I argued in this old Forbes essay, is by literally applying the logic of Moore’s Law to all current and future laws and regulations through two simple principles:

Principle #1 – Every new technology proposal should include a provision sunsetting the law or regulation 18 months after enactment. Policymakers can always reenact the rule if they believe it is still sensible.

Principle #2 – Reopen all existing technology laws and regulations and reassess their worth. If no compelling reason for their continued existence can be identified and substantiated, those laws or rules should be repealed within 18 months. If a rationale for continuing existing laws and regs can be identified, the rule can be re-implemented and Principle #1 applied to it.

What should be the test for determining when technology laws and regulations are retained? That bar should be fairly high. Conjectural harms and boogeyman scenarios can’t be used in defense of new rules or the reenactment of old ones. Policymakers must conduct a robust cost-benefit analysis of all tech rules and then offer a clear showing of tangible harm or actual market failure before enactment or reenactment of any policy.

Of course, this doesn’t leave much room for antitrust law since it almost never moves that fast. But if you think that there is truth in Kang’s “Fast Firms, Slow Regulators” headline, what option do we have but to largely abandon the effort–especially when Moore’s Law and Schumpeterian “creative destruction” do such a better job of keep markets competitive and innovative?

Of course, some academic and regulatory activists like Columbia’s Tim Wu favor a very different sort of regime based on “agency threats” and a preemptive dismantling of the digital economy through the imposition of a “Separations Principle.” The Separations Principle would divide and strictly quarantine the various elements of the tech world — networks, devices, and content — such that vertical integration would become per se illegal. That’s certainly one way of dealing with the “Fast Firms, Slow Regulators” problem! Of course, it would handle that problem by essential decimating much of what makes the digital economy so dynamic and innovative. (I have a new paper coming out shortly that will documented why Wu’s remedy would be such a disaster in practice.)

In any event, it’s good that people are acknowledging that there is a problem here–that antitrust cannot keep pace with the pace of innovation we see in the tech economy–but we must be cautious that this insight does not lead to new or more destructive forms of regulatory adventurism. As I noted in last week’s Forbes column, “The Rule Of Three: The Nature of Competition In The Digital Economy,” there exists a tendency among many to take static snapshots of a sector at any given time and then leap to conclusions about “market power” or “oligopoly.” But competition is a process, not an end-point, and a more sophisticated understanding of the digital economy recognizes how often the borders between sectors are blurred or obliterated by dynamic, disruptive change. Churn is rampant and relentless. Thus, short-term measures of market power are often meaningless since firms can get very big very fast, but they can stumble and fall just as rapidly.

Anyway, if you care to read the very best papers written recently on this topic, you’ll want to check out:

Geoffrey A. Manne & Joshua D. Wright, “Innovation and the Limits of Antitrust,” George Mason Law & Economics Research Paper No. 09-54, February 16, 2010.

J. Gregory Sidak & David J. Teece, “Dynamic Competition in Antitrust Law,” 5 Journal of Competition Law & Economics (2009).

Thomas Hazlett, David Teece, Leonard Waverman, “Walled Garden Rivalry: The Creation of Mobile Network Ecosystems,” George Mason University Law and Economics Research Paper Series, (November 21, 2011), No. 11-50.

Bruce Owen, “Antitrust and Vertical Integration in ‘New Economy’ Industries,” Technology Policy Institute (November 2010).

Daniel F. Spulber, “Unlocking Technology: Antitrust and Innovation,” Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 4(4), 915 (2008).

Richard Posner, “Antitrust in the New Economy,” 68 ANTITRUST L.J. 925, 927 (2001).

Jerry Ellig and Daniel Lin, “A Taxonomy of Dynamic Competition Theories,” in Jerry Ellig (ed.), Dynamic Competition and Public Policy: Technology, Innovation, and Antitrust Issues (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001), 16-44.

Als0 make sure to check out these classic works from ‘Austrian School’ economists:

Israel Kirzner, Discovery and the Capitalist Process (University of Chicago Press, 1985).

F.A. Hayek, “Competition as a Discovery Procedure,” in New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of Ideas (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1978).

Gerald P. O’Driscoll, Jr. & Mario J. Rizzo, “Competition and Discovery,” in The Economics of Time and Ignorance (London: Routledge, 1985, 1996).

Finally, here are a few other essays I have penned on this issue:

“The Rule Of Three: The Nature of Competition In The Digital Economy,” Forbes, June 29, 2012.

“Sunsetting Technology Regulation: Applying Moore’s Law to Washington,” Forbes, May 25, 2012.

“Of “Tech Titans” and Schumpeter’s Vision,” Forbes, August 22, 2011.

“Bye Bye BlackBerry. How Long Will Apple Last?” Forbes, April 1, 2012.

“Gary Reback’s Antitrust Love Letter,” Technology Liberation Front, September 20, 2009.

“What is “Optimal Interoperability”? A Review of Palfrey & Gasser’s’“Interop,’” Technology Liberation Front, June 11, 2012.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower