Adam Thierer's Blog, page 87

August 7, 2012

What Google Fiber Says about Tech Policy: Fiber Rings Fit Deregulatory Hands

Google’s first lesson for building affordable, one Gbps fiber networks with private capital is crystal clear: If government wants private companies to build ultra high-speed networks, it should start by waiving regulations, fees, and bureaucracy.

Executive Summary

For three years now the Obama Administration and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) have been pushing for national broadband connectivity as a way to strengthen our economy, spur innovation, and create new jobs across the country. They know that America requires more private investment to achieve their vision. But, despite their good intentions, their policies haven’t encouraged substantial private investment in communications infrastructure. That’s why the launch of Google Fiber is so critical to policymakers who are seeking to promote investment in next generation networks.

The Google Fiber deployment offers policymakers a rare opportunity to examine policies that successfully spurred new investment in America’s broadband infrastructure. Google’s intent was to “learn how to bring faster and better broadband access to more people.” Over the two years it planned, developed, and built its ultra high-speed fiber network, Google learned a number of valuable lessons for broadband deployment – lessons that policymakers can apply across America to meet our national broadband goals.

To my surprise, however, the policy response to the Google Fiber launch has been tepid. After reviewing Google’s deployment plans, I expected to hear the usual chorus of Rage Against the ISP from Public Knowledge, Free Press, and others from the left-of-center, so-called “public interest” community (PIC) who seek regulation of the Internet as a public utility. Instead, they responded to the launch with deafening silence.

Maybe they were stunned into silence. Google’s deployment is a real-world rejection of the public interest community’s regulatory agenda more powerful than any hypothetical. Google is building fiber in Kansas City because its officials were willing to waive regulatory barriers to entry that have discouraged broadband deployments in other cities. Google’s first lesson for building affordable, one Gbps fiber networks with private capital is crystal clear: If government wants private companies to build ultra high-speed networks, it should start by waiving regulations, fees, and bureaucracy.

That’s the policy template that worked for the residents of Kansas City. It could work for the rest of America too, but only if all broadband providers receive the same treatment. When private companies compete on a level playing field, consumers always win. When government regulations mandate a particular business model or favor a particular competitor, bureaucracy is the only winner – everyone else loses.

Maybe the silence of PIC advocates indicates they’ve had a change of heart. Although PIC has violently opposed the efforts of other broadband providers to eliminate similar regulatory barriers in the past, perhaps the success of Google Fiber has persuaded them that deregulatory policies fairly applied to all competitors are essential to meeting our nation’s shared goal of national broadband connectivity.

Google’s deployment certainly indicates the PIC would benefit from a change in their approach to policy. The Google Fiber business model contradicts virtually every element of the PIC’s current regulatory agenda.

PIC says restrictive regulations don’t discourage new investment. Google says it passed over proposals by cities in California due to restrictive regulations.

PIC says the government should limit the delivery of “specialized” IP-based video services by network operators. Google says specialized video services support fiber deployment.

PIC says that the provision of subsidized devices by network operators harms innovation and term contracts harm consumers. Google says bundling its own, vertically integrated computing devices with its fiber network services in exchange for a two-year contract commitment is part of the “Full Google Experience.”

PIC says the “open access” model is “easy” and viable even in competitive markets. Google says it abandoned its commitment to open access because it doesn’t think anyone else can deliver service as well as it can.

PIC says the “end-to-end” regulatory model, which severs all business relationships between “core” network infrastructure and “edge” elements of the network, promotes innovation and investment. Google says we should explore alternatives to the “end-to-end” model, including vertical integration among network operators and edge providers.

Every level of our government could benefit from a change in its policy approach as well. If we are serious about achieving affordable, ultra high-speed broadband connectivity for every American, we must question the traditional assumptions underlying our legacy regulatory approach. Google Fiber demonstrates that the problem isn’t deregulation, a lack of competition, or an unwillingness to invest in American infrastructure. It’s the imposition of burdensome bureaucracy, unnecessary costs, and political favoritism at all levels of government. Eliminating these regulatory barriers would drive investment in America’s infrastructure, spur innovation, create jobs, and grow the economy while helping to meet President Obama’s goal of connecting every American to broadband.

Google has shown the way. Is government willing to let other competitors in the marketplace follow the same path?

Introduction

The story begins two years ago, when Google announced its plans to build experimental, ultra high-speed broadband networks and operate them on an “open access” basis. Over 1,100 communities asked Google to build a network in their area, including several “desperate cities” willing to change their names and even swim with sharks. Google ultimately chose Kansas City as its broadband mecca.

So far, people in this prosperous city on the plains are embracing Google Fiber with enthusiasm. A little over a week after Google offered designated areas an opportunity to request service, 46 neighborhoods had qualified. Analysts estimate Google has already achieved approximately 4 percent market penetration. Google’s bet on an all-IP, fiber network appears poised for early success in Kansas City, which is something every tech geek should be pleased to see.

Like most new enterprises, it’s unclear whether Google Fiber will enjoy financial success in the long term. Many analysts are skeptical that Google’s business model can be replicated on a larger scale. Others believe it will deliver a “knock-out punch” to existing cable and telecom operators. Though I have my doubts, I’m content to let the market determine Google Fiber’s financial fate.

I’m more intrigued by the public policy implications of the Google Fiber business plan. Am I the only one who is baffled by the unusual response to Google’s announcement? After reviewing Google Fiber’s terms of service, I expected to hear the usual chorus of Rage Against the ISP from Public Knowledge, Free Press, and other PIC advocates who believe the Internet should be a public utility. I also expected the technology press would be critical of several elements of Google’s service. I was surprised on both counts.

Many in the tech press are offering gushing praise for Google’s new service. BGR says Google Fiber is a “ridiculously awesome value” for “lucky” Kansas City residents. CNET suggests that the Google Fiber business model offers the “rest of the broadband industry” a template for successful deployment of one Gbps networks: “Google is showing the cable companies and telecommunications providers how a broadband network should be built.”

The notion that other ISPs should mimic Google Fiber may explain why PIC advocates have been so deafeningly silent on the Kansas City deployment. The PIC narrative says that “the evil folks at cable companies and telecoms” are sabotaging fiber deployment in order to maintain their legacy businesses. Google doesn’t have a legacy network business, and its informal corporate motto is “don’t be evil.” So, according to the PIC narrative, Google’s business model shouldn’t look anything like those implemented by existing ISPs.

It turns out that Google’s business model validates a host of existing industry practices that PIC advocates seek to outlaw or regulate, and demonstrates that existing regulations are the biggest factor inhibiting the deployment of all-IP fiber networks by other service providers. Ironically, to the extent Google’s business model does differ significantly from those typical of other ISPs, it relies on an industry structure – vertical integration – PIC advocates vociferously oppose. As the following analysis of the “lessons learned” from Google Fiber demonstrates in detail, Google’s model contradicts virtually every element of the PIC regulatory agenda.

First Lesson Learned: Deregulation promotes private investment

The first lesson Google learned from its fiber project: If government wants private companies to build ultra high-speed networks, it should start by waiving regulations, fees, and bureaucracy.

It’s no accident that Google chose to deploy its broadband network in a city subject to deregulatory statewide video franchising laws (in Kansas and Missouri). (Federal law prohibits the provision of video programming services without a “franchise”.)

Franchises were historically granted by local county or municipal governments who gave virtual monopolies to cable providers in exchange for “universal service” commitments (i.e., commitments to build the cable network to every neighborhood irrespective of cost or demand). Although federal law has prohibited monopoly video franchises since 1992, when potential new entrants asked permission to build competitive cable networks, local franchising authorities often stonewalled their applications or demanded unreasonable concessions. When new entrants challenged the legality of these tactics, PIC advocates derided the potential competitors for attempting to enter the market.

In 2006, the FCC adopted an order prohibiting local franchising authorities from unreasonably refusing to award competitive franchises for video service. The FCC found that many local franchising regulations were “unreasonable barriers to entry” in the video market and were “discourage[ing] investment in the fiber-based infrastructure necessary for the provision of advanced broadband services.” The unreasonable regulations included excessive build-out mandates, the inclusion of non-video revenue in franchise “fees” (including advertising fees), and demands unrelated to the provision of video service. The FCC has since reported that 20 states have enacted statewide video franchising laws to streamline the delivery of video service.

PIC advocates opposed this deregulatory decision when it was made and continue to oppose it. When the FCC announced its decision, Harold Feld, then Senior Vice President of the Media Access Project, said preempting local franchise regulation would “deprive the public of the best way to guarantee that cable providers and competitors meet the needs of their local communities.” When states began implementing the decision through statewide franchising laws, Sascha Meinrath, Director of the New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute, attacked such legislation for providing build-out waivers even when developments are “inaccessible using reasonable technical solutions.” Despite evidence of significant competitive entry in the video market since the FCC preempted unreasonable local franchising regulations, many PIC advocates still believe deregulation has had no positive impact.

This brief history of video franchising isn’t merely academic. Absent deregulation of local franchising in Kansas City, Google Fiber’s business model wouldn’t have been possible. When Time Warner Cable became the principal video service provider in the Kansas City market decades ago, its franchise required that it build its network to virtually every neighborhood, including areas that pose geographic challenges and neighborhoods where residents are less likely to subscribe. A monopolist can fund (i.e., cross-subsidize) uneconomic construction by raising prices in other neighborhoods. In a competitive market, however, cross-subsidization mandates typically inhibit entry. For example, New York City delayed Verizon’s FiOS deployment for nearly a year while the city negotiated a requirement that Verizon build its network in all five boroughs of the city.

In Kansas City, Google doesn’t have a build-out requirement. It will offer service only to neighborhoods that demonstrate their potential to cover the costs of construction. Google divided Kansas City into a number of small neighborhoods and then cherry picked the areas where it would be willing to offer service. It then set preregistration goals for these neighborhoods based on their size, density, and ease of construction. Eligible neighborhoods have six weeks to meet their preregistration goals. If they don’t, Google won’t construct its network in that area. In neighborhoods that are more expensive to build,Google says it wants to make sure that enough residents want its service before committing capital to network construction. There is “no need to dispatch crews and rip up asphalt in pursuit of a handful of potential customers when Google can laser in on the most eager concentrations of subscribers.”

Although it wasn’t required to obtain a municipal franchise, Google received stunning regulatory concessions and incentives from local governments, including free access to virtually everything the city owns or controls: rights of way, central office space, power, interconnections with anchor institutions, marketing and direct mail, and office space for Google employees. City officials also expedited the permitting process and assigned staff specifically to help Google. One county even offered to allow Google to hang its wires on parts of utility poles – for free – that are usually off-limits to communications companies.

The key element for Google was that Kansas City officials promised to stay out of the way. When Google’s vice president of access services, Milo Medin, was asked why Google chose Kansas City for its fiber deployment, he said, “We wanted to find a location where we could build quickly and efficiently.” In his testimony before Congress last year, Medin emphasized that “regulations – at the federal, state, and local levels – can be central factors in company decisions on investment and innovation.” Based on his experience with Google Fiber, he concluded that government regulation “often results in unreasonable fees, anti-investment terms and conditions, and long and unpredictable build-out timeframes” that “increase the cost and slow the pace of broadband network investment and deployment.”

Second Lesson Learned: Specialized Video Services Support Fiber Deployment

The second lesson Google learned from its fiber project: Specialized video services help support the costs of fiber deployment.

In its order preempting unreasonable local franchise regulations, the FCC found that broadband deployment and video entry are “inextricably linked,” because broadband providers require the revenue from video services to offset the costs of fiber deployment. The FCC affirmed this finding in its 2010 net neutrality order, which exempted “specialized services”, including Internet Protocol-based video offerings, from net neutrality regulations. The FCC recognized that specialized video services “may drive additional private investment in broadband networks and provide end users valued services” that support the open Internet.

The Google Fiber business model indicates the FCC was right – specialized video services do help support the costs of fiber deployment. When it initially announced its fiber project, Google did not intend to offer specialized video services at all. Little more than a year ago, Google remained focused only on Internet connectivity and still had no plans to provide video services; though it said it wanted to “hear from Kansas City residents what additional services they would find most valuable.” By the time it launched the project, Google had decided to center its highest subscription rate on a new, specialized video service (Google Fiber TV) that Google says is “designed for how you watch today and how you’ll watch tomorrow.” It appears that, after listening to Kansas City residents, Google learned that many consumers want their ISP to offer specialized video services.

PIC advocates generally oppose any form of specialized service based on IP, especially video services. Less than a week after Google launched its own, IP-based video service, Public Knowledge filed a petition at the FCC arguing that Comcast’s specialized Xfinity video service is discriminatory and illegal. Although the petition is based on conditions imposed on the Comcast/NBC-Universal merger, Public Knowledge says the service may violate the FCC’s net neutrality rules as well.

Third Lesson Learned: Equipment Subsidies Offer Benefits to Consumers

The third lesson Google learned from its fiber project: Equipment subsidies coupled with term contracts offer benefits to consumers.

The Google Fiber business model also embraces the standard communications industry practice of offering consumers subsidized equipment in exchange for term contracts. Consumers who opt for “The Full Google Experience” will get four devices, including a set-top box, a network box, a storage box, and a new tablet for use as a “remote control”, subject to a two-year contract.

Bundling branded set-top boxes and other devices is standard practice in the video industry, but Google’s approach is new in at least one respect: The tablet is a Google Nexus 7 running Google’s Android OS, a powerful computing device that is capable of far more than controlling a television set. Google is also offering the option of buying a “Chromebook” laptop for as little as $299 – slightly less than the amount of the “construction fee” Google is waiving for premium customers. By bundling its own, vertically integrated computing devices with its premium service, Google can leverage its fiber network to gain market share from the makers of other devices, software, and operating systems, including Apple and Microsoft.

Though I think it’s a savvy move that could have a long-lasting impact on the communications marketplace, I’m surprised that the PIC has said nothing about this new wrinkle on device bundling. On March 30, 2012, Public Knowledge released a paper asserting that subsidized video devices harm innovation. The paper says innovation suffers because it’s easier to attach devices provided by the video service provider, and most consumers “just find it simpler to settle for whatever device their cable company offers.” It also contends that the subsidized device model is unusual, and notes “no one rents their computer from their ISP.” I suppose that’s still true. Google isn’t renting the Nexus 7 – it’s giving it away (and subsidizing the Chromebook by waiving the construction fee).

Fourth Lesson Learned: Open Access Isn’t Viable in Competitive Markets

The fourth lesson Google learned from its fiber project: Open access isn’t a viable business model in competitive markets.

When Google originally announced its intention to build its fiber network and operate it on an “open access” basis, Susan Crawford said we would “learn how easy it is” to allow competitive access to fiber networks and how little such networks cost. What we actually learned from Google Fiber is that “open access” isn’t a viable business model in a competitive market. Once Google analyzed how fiber networks are financed, built, and operated, it abandoned its earlier commitment to open access and decided not to allow other ISPs on its network. According to Google Fiber project manager Kevin Lo, “We don’t think anybody else can deliver a gig the way we can.” Translation: Open access doesn’t make financial sense in a competitive environment.

It’s still possible that Google could open its network to other ISPs in the future, but I suspect that in short term, Google’s reversal will dampen, if not extinguish, the PIC dream of open access networks in competitive markets.

Fifth Lesson Learned: Vertical Integration Offers an Alternative to the End-to-End Principle

The fifth lesson Google learned from its fiber project: Vertical integration among “edge” and “infrastructure” providers offers an alternative to the “end-to-end” principle.

The elements of Google Fiber’s business model discussed so far affirm existing industry practice (and free market regulatory theory). In one respect, however, the Google model differs significantly from industry practice. Google is offering free Internet service, albeit limited to 5 Mbps, for seven years to customers who pay the “construction fee.” That speed is just fast enough to support Google’s primary advertising business, including the delivery of video advertisements, but just slow enough to avoid cannibalizing Google Fiber’s premium Internet and video services.

Even so, some analysts predict Google will lose money on its free service. So why would Google offer it? Because Google’s “core advertising business is so powerful, dominant and profitable that it can subsidize almost everything else the company does, using Free to get customers in new markets.” Chris Anderson, the author of “FREE: The Future of a Radical Price,” has asked whether that’s fair when Google’s competitors don’t have a similar golden goose. Google’s response: “If a company chooses to use its profits from one product to help provide another product to consumers at low cost, that’s generally a good thing” (in the absence of tying arrangements).

On its own, Google’s willingness to subsidize broadband access to promote its advertising services might be unremarkable. But, when combined with its provision of a “free” Nexus 7 table and a subsidized Chromebook, it suggests that Google is willing to explore alternatives to the pure end-to-end Internet religion (practiced by PIC advocates and tech evangelists) in favor of a vertically integrated approach. The end-to-end purist believes core network infrastructure should be economically severed from the “edge” of the network, i.e., that Internet access should be offered entirely separately from the services, devices, applications that use network infrastructure. Strict adherence to this principle would prohibit the subsidization of network architecture by profits derived from services (e.g., specialized video and advertising), devices, and applications. Google was thought to be an end-to-end purist, but, assuming that were once true, it appears the company’s views have shifted.

What if large Internet “edge” companies – Google, Apple, and Microsoft – were vertically integrated with the large infrastructure providers – Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T? If the government allowed that to happen, it’s possible that the enormous profits generated by the edge companies (Apple is one of the most valuable companies in the world) would be used to rapidly drive ultra high-speed network deployment rather than fill cash coffers in offshore banks. Google is sitting on $43 billion overseas. Apple has more than $81 billion and Microsoft has $54 billion. By comparison, Verizon currently has about $10 billion in cash, which is less than one quarter of Google’s overseas holdings.

The reality of the Internet economy is that the “edge” generates more revenue than the “core”. In 2011,Comcast produced $8.7 billion in revenue from the sale of high-speed Internet access service. Google produced $37.9 billion in revenue, 96 percent of which was derived from advertising services.

While Google and other edge companies are content to let massive profits sit overseas, America’s network owners are reinvesting their capital in America. AT&T and Verizon ranked first and second, respectively, among U.S.-based companies by their U.S. capital spending in 2011, with Comcast coming in eighth. Google and Apple were ranked 24th and 25th, respectively, with approximately $2 billion in U.S. capital spending each. In 2011, AT&T alone invested ten times that much capital ($20.1 billion) in America. If companies like Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T had access to edge company capital, it could create a new broadband boom.

I’m not sure the edge companies are interested in a vertical integration model, and I’m reasonably certain the current administration wouldn’t allow it. But, now that Google has dipped its toes in the water, it might be a discussion worth having.

Facebook Tests the Waters of ’Net Gambling

Facebook has quietly launched a real-money online gambling application in the U.K., marking a major thrust of the social networking site into online gambling.

The Financial Times is reporting that starting today, Facebook will offer users in the U.K. ages 18 and over online bingo and slots for cash prizes. Slate.com picked up the story this afternoon.

“Gambling is very popular and well regulated in the U.K. For millions of bingo users it’s already a social experience [so] it makes sense [for us] to offer that as well,” Julien Codorniou, Facebook’s head of gaming for Europe, Middle East and Africa, told the Financial Times.

It’s telling in and of itself that Facebook has a gaming chief for the EMEA region. The synergies of social media and gambling has been seriously discussed for several years, mostly in foreign venues, as the U.S. government until recently, has been hostile toward Internet gambling.

However, the recent thaw on the part of the Department of Justice, seen most recently in its settlement (don’t-call-it-an-exoneration) with PokerStars, plus state action toward legalization in in states such as Nevada and Delaware, point to eventual legalization of Internet gambling in the U.S.

In that respect, look for Facebook to be ready. Research from The Innovation Group, a gaming marketing research company, shows that more than half the users on online gaming come in through social media or search. Companies such as Zynga, which began by offering multiplayer social games such as Cityville, Castleville and Mafia Wars on Facebook, are particularly well-positioned. Zynga’s most popular on-line game is poker, and Zynga and companies like it have a logical growth path into online gambling. Given their established connection with social networks, it’s a good shot we’ll see virtual online casino environments emerge within social networks such as Facebook, Google+, Orkut and others.

The natural convergence of social media and gaming environments has been explored fairly extensively. European researchers such as Jani Kinnunen of the Game Research Lab at Finland’s University of Tampere finds this running both ways. As social networks explore gaming, gaming sites explore social networking.

Skill gaming sites can be excellent examples of new forms of gambling. Casual web-browser based games (any game can be a gambling game). Players can place a monetary bet on their games and play against each other, which requires social interaction between player.

Moreover, games and game-related interaction don’t have to be situated in the same place. Kinnunen notes that online poker sites and player forums are usually separated. Poker forums are online communities where players can interact with each other before and after playing, communicating, learning new skills, exchanging tips for good gaming sites and so on.

What we have yet to learn is how Facebook is setting up age-verification and security procedures, as well as location-based restrictions. All of these will be part of the picture once Internet gambling moves forward in the U.S., and they represent technology skill strengths Americans have. The central takeaway today, however, is that a major U.S. company has entered the international online gambling market, where legitimacy has long been established. Facebook’s move is another step toward extending that legitimacy to the U.S.

Stefan Krappitz on Troll Culture

Stefan Krappitz, writer of the book Troll Culture: A Comprehensive Guide, discusses the phenomenon of internet trolling. For Krappitz trolling is disrupting people for personal amusement. Trolling is largely a positive phenomenon argues Krappitz. While it can become very negative in some cases, for the most part trolling is simply an amusing practice that is no different than playing practical jokes. Krappitz believes that trolling has been around since before the age of the internet. He notes that the behavior of Socrates is reminiscent of trolling because he pretended to be a student and then used his questioning to mock people who did not know what they were talking about. Krappitz also discusses anonymity and how it contributes and takes away from trolling as well as discussing where the line is between good trolling and cyber-bullying.

Related Links

“Troll Culture: A Comprehensive Guide” , by Krappitz

“How the Internet Beat Up and 11-Year-Old Girl” by Gawker

“Forever Alone Involuntary Flashmob”, Vice

“The Trolls Among Us”, New York Times

“Trolling for Ethics: Mattathias Schwartz’s Awesome Piece on Internet Poltergeists”, New York Times

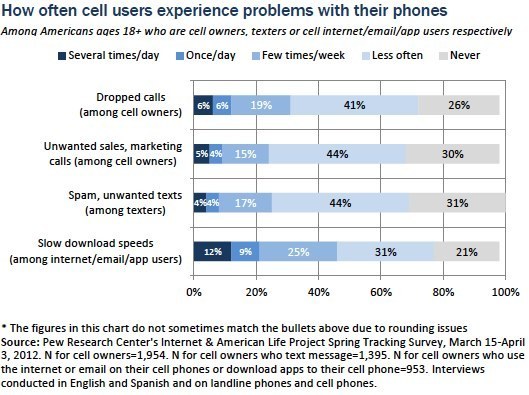

Users Experience Symptoms of the Spectrum Crunch

Some 77 percent of wireless phone users who use their phones for online access say slow download speeds plague their mobile applications, according to a new survey from the Pew Internet and American Life Project. Of the same user group, 46 percent said they experienced slow download speeds at least once a week or more frequently (see chart below).

While the report, published last week, does not delve into the reasons behind the service problems, it does offer evidence that users are noticing the quality issues wireless congestion is creating. Slow download speeds are a function of available bandwidth for mobile data services. Bandwidth requires spectrum. The iPhone, for instance, uses 24 times as much spectrum as a conventional cell phone, and the iPad uses 122 times as much, according to the Federal Communications Commission. As more smartphones contend for more bandwidth within a given coverage area, connections slow or time out. Service providers and analysts have warned that the growing use of wireless smartphones and tablets, without an increase in spectrum, would begin to degrade service. There have been plenty of anecdotal instances of this. Pew offers some quantitative measurement.

While technologies such from cell-splitting to 4G offer temporary fixes, the quality issue will not be fully addressed until the government frees up more spectrum. While the FCC hasn’t helped much by blocking the AT&T-T-Mobile merger and joining with the Department of Justice in delaying the Verizon deal to lease unused spectrum from the cable companies, at least the agency has acknowledged the problem. Right now, as Larry Downes reported last week, the National Telecommunications and Information Agency (NTIA), which has been charged with the task of identifying spectrum the government can vacate, is stalling. It would be nice to see the FCC apply the aggressiveness it brings to industry regulation to getting NTIA off the schneid. At the same time, the Commission needs to put aside its ideological bent and do what it can to make more spectrum available in the short term.

August 6, 2012

What Google Fiber, Gig.U, and US Ignite say about Regulatory Waste and Overload

On Forbes today, I have a long article on the progress being made to build gigabit Internet testbeds in the U.S., particularly by Gig.U.

On Forbes today, I have a long article on the progress being made to build gigabit Internet testbeds in the U.S., particularly by Gig.U.

Gig.U is a consortium of research universities and their surrounding communities created a year ago by Blair Levin, an Aspen Institute Fellow and, recently, the principal architect of the FCC’s National Broadband Plan. Its goal is to work with private companies to build ultra high-speed broadband networks with sustainable business models .

Gig.U, along with Google Fiber’s Kansas City project and the White House’s recently-announced US Ignite project, spring from similar origins and have similar goals. Their general belief is that by building ultra high-speed broadband in selected communities, consumers, developers, network operators and investors will get a clear sense of the true value of Internet speeds that are 100 times as fast as those available today through high-speed cable-based networks. And then go build a lot more of them.

Google Fiber, for example, announced last week that it would be offering fully-symmetrical 1 Gbps connections in Kansas City, perhaps as soon as next year. (By comparison, my home broadband service from Xfinity is 10 Mbps download and considerably slower going up.)

US Ignite is encouraging public-private partnerships to build demonstration applications that could take advantage of next generation networks and near-universal adoption. It is also looking at the most obvious regulatory impediments at the federal level that make fiber deployments unnecessarily complicated, painfully slow, and unduly expensive.

I think these projects are encouraging signs of native entrepreneurship focused on solving a worrisome problem: the U.S. is nearing a dangerous stalemate in its communications infrastructure. We have the technology and scale necessary to replace much of our legacy wireline phone networks with native IP broadband. Right now, ultra high-speed broadband is technically possible by running fiber to the home. Indeed, Verizon’s FiOS network currently delivers 300 Mbps broadband and is available to some 15 million homes.

But the kinds of visionary applications in smart grid, classroom-free education, advanced telemedicine, high-definition video, mobile backhaul and true teleworking that would make full use of a fiber network don’t really exist yet. Consumers (and many businesses) aren’t demanding these speeds, and Wall Street isn’t especially interested in building ahead of demand. There’s already plenty of dark fiber deployed, the legacy of earlier speculation that so far hasn’t paid off.

So the hope is that by deploying fiber to showcase communities and encouraging the development of demonstration applications, entrepreneurs and investors will get inspired to build next generation networks.

Let’s hope they’re right.

What interests me personally about the projects, however, is what they expose about regulatory disincentives that unnecessarily and perhaps fatally retard private investment in next-generation infrastructure. In the Forbes piece, I note almost a dozen examples from the Google Fiber development agreement where Kansas City voluntarily waived permits, fees, and plodding processes that would otherwise delay the project. As well, in several key areas the city actually commits to cooperate and collaborate with Google Fiber to expedite and promote the project.

As Levin notes, Kansas City isn’t offering any funding or general tax breaks to Google Fiber. But the regulatory concessions, which implicitly acknowledge the heavy burden imposed on those who want to deploy new privately-funded infrastructure (many of them the legacy of the early days of cable TV deployments), may still be enough to “change the math,” as Levin puts it, making otherwise unprofitable investments justifiable after all.

Just removing some of the regulatory debris, in other words, might itself be enough to break the stalemate that makes building next generation IP networks unprofitable today.

The regulatory cost puts a heavy thumb on the side of the scale that discourages investment. Indeed, as fellow Forbes contributor Elise Ackerman pointed out last week, Google has explicitly said that part of what made Kansas City attractive was the lack of excessive infrastructure regulation, and the willingness and ability of the city to waive or otherwise expedite the requirements that were on the books.(Despite the city’s promises to bend over backwards for the project, she notes, there have still been expensive regulatory delays that promoted no public values.)

Particularly painful to me was testimony by Google Vice President Milo Medin, who explained why none of the California-based proposals ever had a real chance. “Many fine California city proposals for the Google Fiber project were ultimately passed over,” he told Congress, “in part because of the regulatory complexity here brought about by [the California Environmental Quality Act] and other rules. Other states have equivalent processes in place to protect the environment without causing such harm to business processes, and therefore create incentives for new services to be deployed there instead.”

Ouch.

This is a crucial insight. Our next-generation communications infrastructure will surely come, when it does come, from private investment. The National Broadband Plan estimated it would take $350 billion to get 100 Mbps Internet to 100 million Americans through a combination of fiber, cable, satellite and high-speed mobile networks. Mindful of reality, however, the plan didn’t even bother to consider the possibility of full or even significant taxpayer funding to reach that goal.

Of course, nationwide fiber and mobile deployments by network operators including Verizon and AT&T can’t rely on gimmicks like Google Fiber’s hugely successful competition, where 1,100 communities applied to become a test site. Nor can they, like Gig.U, cherry-pick research university towns, which have the most attractive demographics and density to start with. Nor can they simply call themselves start-ups and negotiate the kind of freedom from regulation that Google and Gig.U’s membership can.

Large-scale network operators need to build, if not everywhere, than to an awful lot of somewheres. That’s a political reality of their size and operating model, as well as the multi-layer regulatory environment in which they must operate. And it’s a necessity of meeting the ambitious goal of near-universal high-speed broadband access, and of many of the applications that would use it.

Unlike South Korea, we aren’t geographically-small, with a largely urban population living in just a few cities. We don’t have a largely- nationalized and taxpayer-subsidized communications infrastructure. On a per-person basis, deploying broadband in the U.S. is much harder, complicated and more expensive than it is in many competing nations in the global economy.

Under the current regulatory and economic climate, large-scale fiber deployment has all but stopped for now. Given the long lead-time for new construction, we need to find ways to restart it.

So everyone who agrees that universal broadband is a critical element in U.S. competitiveness in the next decade or so ought to look closely at the lessons, intended or otherwise, of the various testbed projects. They are exposing in painful detail a dangerous and useless legacy of multi-level regulation and bureaucratic inefficiency that makes essential private infrastructure investment economically impossible.

Don’t get me wrong. The demonstration projects and testbeds are great. Google Fiber, Gig.U, and US Ignite are all valuable efforts. But if we want to overcome our “strategic bandwidth deficit,” we’ll need something more fundamental than high-profile projects and demonstration applications. Most of all, we need a serious housecleaning of legacy regulation at the federal, state, and local level.

Regulatory reform might not be as sexy as gigabit Internet demonstrations, but the latter ultimately won’t make much difference without the former. Time to break out the heavy demolition equipment—for both.

August 2, 2012

PokerStars, Full Tilt Poker, the U.S. Attorney and What Just Happened

Yesterday brought a spate of news reports, many of them inaccurate or oversimplified, about a settlement the U.S. Attorney’s office in Manhattan reached with two major international Internet poker sites—PokerStars and Full Tilt Poker.

The buried lead–and very good news for online poker players–is that Internet poker site PokerStars is back in business. Manhattan U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara ended his case against the site and it is now free to re-enter the U.S. market when states begin permitting Internet gambling, which could start as early as this year in states such as Nevada and Delaware.

The three-way settlement itself is rather complicated. Full Tilt Poker will have to forfeit all of its assets, at this point mostly property, to the U.S. government. PokerStars will then acquire those forfeited Full Tilt Poker assets from the feds in return for its own forfeiture of $547 million. PokerStars also agreed to make available $184 million in funds in deposits held by non-U.S. Full Tilt players, money players believed was lost.

The U.S. government seized these funds on April 15, 2011 when it shut down Full Tilt, PokerStars and a third site, Absolute Poker, on charges of money laundering. The date has become known as Black Friday in the poker community. Specifically, the three sites were charged with violation of the 2006 Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (UIGEA), which prohibited U.S. banks from transferring funds to off-shore Internet poker and gambling sites. To combat the measure, sites such as PokerStars and Full Tilt began using payment processors that allegedly lied to U.S. banks about their ties to gambling sites. Although this would be fraud under the letter of the law, the U.S. government never claimed payment processors stole money from players or banks and no evidence suggests they did.

What the shutdown did reveal, however, was a shortfall in player deposits at Full Tilt, which led prosecutors to charge that Full Tilt was illegally paying investors out of player funds in a Ponzi-like scheme. Those charges, which look to be more serious then the UIGEA violations, still have yet to be resolved. The deal prohibits Full Tilt management and investors to have roles in PokerStars.

PokerStars, however, is clean. In the settlement the site admits no wrongdoing. While $547 million is far from nominal, it’s a far cry from the money-laundering convictions and 20-year prison sentences that were talked up when the charges were first brought. In reality, the resolution of the case is PokerStar’s takeover of one of its largest competitors and the opportunity to reposition itself for the U.S. market, perhaps getting its deal with Wynn Resorts back on track.

If you see something truly punitive here, please comment. The arrangement actually appears to be another concession by the government on Internet gambling. The first, and still most significant, was the Department of Justice’s December 2011 memo to Illinois and New York saying the Wire Act does not prevent them from selling lottery tickets online—or offering any other wagering game on the Internet–as long as customers are in-state. That decision opened the door to state Internet gambling legislation and several states have jumped at it. The New York settlement also strengthens the contention, voiced by some in the gaming law community, that the government, faced with pressure from states who covet tax revenue, the unpopularity of the Internet gambling prohibition, and the difficulty in winning convictions, may eventually grant some sort of general amnesty just to get free of what was, at the end of the day, a political compromise to appease a handful of moralists in Congress.

The PokerStars settlement, while allowing U.S. Attorney Bharara to save face, may be the first step toward that.

Hat tip to Hard Boiled Poker, a blog that adeptly clarifies the media’s inaccuracies and oversights in reporting this story as well outing the inability of CNNmoney.com’s editors to tell the difference between a blackjack and poker layout. The blog commends Forbes.com’s coverage as the best for grasping the settlement’s significance.

FTC sacrifices the rule of law for more flexibility; Commissioner Ohlhausen wisely dissents

On July 31 the FTC voted to withdraw its 2003 Policy Statement on Monetary Remedies in Competition Cases. Commissioner Ohlhausen issued her first dissent since joining the Commission, and points out the folly and the danger in the Commission’s withdrawal of its Policy Statement.

The Commission supports its action by citing “legal thinking” in favor of heightened monetary penalties and the Policy Statement’s role in dissuading the Commission from following this thinking:

It has been our experience that the Policy Statement has chilled the pursuit of monetary remedies in the years since the statement’s issuance. At a time when Supreme Court jurisprudence has increased burdens on plaintiffs, and legal thinking has begun to encourage greater seeking of disgorgement, the FTC has sought monetary equitable remedies in only two competition cases since we issued the Policy Statement in 2003.

In this case, “legal thinking” apparently amounts to a single 2009 article by Einer Elhague. But it turns out Einer doesn’t represent the entire current of legal thinking on this issue. As it happens, Josh Wright and Judge Ginsburg looked at the evidence in 2010 and found no evidence of increased deterrence (of price fixing) from larger fines:

If the best way to deter price-fixing is to increase fines, then we should expect the number of cartel cases to decrease as fines increase. At this point, however, we do not have any evidence that a still-higher corporate fine would deter price-fixing more effectively. It may simply be that corporate fines are misdirected, so that increasing the severity of sanctions along this margin is at best irrelevant and might counter-productively impose costs upon consumers in the form of higher prices as firms pass on increased monitoring and compliance expenditures.

Commissioner Ohlhausen points out in her dissent that there is no support for the claim that the Policy Statement has led to sub-optimal deterrence and quite sensibly finds no reason for the Commission to withdraw the Policy Statement. But even more importantly Commissioner Ohlhausen worries about what the Commission’s decision here might portend:

The guidance in the Policy Statement will be replaced by this view: “[T]he Commission withdraws the Policy Statement and will rely instead upon existing law, which provides sufficient guidance on the use of monetary equitable remedies.” This position could be used to justify a decision to refrain from issuing any guidance whatsoever about how this agency will interpret and exercise its statutory authority on any issue. It also runs counter to the goal of transparency, which is an important factor in ensuring ongoing support for the agency’s mission and activities. In essence, we are moving from clear guidance on disgorgement to virtually no guidance on this important policy issue.

An excellent point. If the standard for the FTC issuing policy statements is the sufficiency of the guidance provided by existing law, then arguably the FTC need not offer any guidance whatever.

But as we careen toward a more and more active role on the part of the FTC in regulating the collection, use and dissemination of data (i.e., “privacy”), this sets an ominous precedent. Already the Commission has managed to side-step the courts in establishing its policies on this issue by, well, never going to court. As Berin Szoka noted in recent Congressional testimony:

The problem with the unfairness doctrine is that the FTC has never had to defend its application to privacy in court, nor been forced to prove harm is substantial and outweighs benefits.

This has lead Berin and others to suggest — and the chorus will only grow louder — that the FTC clarify the basis for its enforcement decisions and offer clear guidance on its interpretation of the unfairness and deception standards it applies under the rubric of protecting privacy. Unfortunately, the Commission’s reasoning in this action suggests it might well not see fit to offer any such guidance.

[Cross posted at TruthontheMarket]

The Long and Short on Internet Tax

Steve Titch gave you a thorough run-down last week. Now Tim Carney has a quick primer on the push by big retailers to increase tax collection on goods sold online.

S. 1832, the Marketplace Fairness Act currently enjoys no affirmative votes on WashingtonWatch.com. Good.

August 1, 2012

Brazilian Interview with Touré on WCIT

Today is a a big day for WCIT: Ambassador Kramer gave a major address on the US position and the Bono Mack resolution is up for a vote in the House. But don’t overlook this Portuguese language interview with ITU Secretary-General Hamadoun Touré.

In the interview, Secretary-General Touré says that we need $800 billion of telecom infrastructure investment over the next five years. He adds that this money is going to have to come from the private sector, and that the role of government is to adopt dynamic regulatory policies so that the investment will be forthcoming. It seems to me that if we want dynamism in our telecom sector, then we should have a free market in telecom services, unencumbered by…outdated international regulatory agencies such as the ITU.

The ITU has often insisted that it has no policy agenda of its own, that it is merely a neutral arbiter between member states. But in the interview, Secretary-General Touré calls the ETNO proposal “welcome,” categorically rejects Internet access at different speeds, and spoke in favor of global cooperation to prevent cyberwar. These are policy statements, so it seems clear that the ITU is indeed pursuing an agenda. And when the interviewer asks if Dr. Touré sees any risks associated with greater state involvement in telecom, he replies no.

If you’re following WCIT, the full interview is worth a read, through Google Translate if necessary. Hat tip goes to the Internet Society’s Scoop page for WCIT.

July 31, 2012

Defending Limits on State Tax Powers

The U.S. Senate holds hearings Wednesday on the so-called Market Fairness Act (S. 1832), which would be better dubbed the “Consumer and Enterprise Unfairness Act,” as it seeks to undo a critical requirement that prevents states from engaging in interstate tax plunder.

In a series of court decisions that stretch back to the 1950s, the courts have consistently affirmed that a business must have a physical presence within a state in order to be compelled to collect sales taxes set by that state and any local jurisdiction.

That meant catalogue and mail order businesses were not required to collect sales tax from customers in any other state but their own. The three major decision that serve as the legal foundation for this rule, including Quill v. North Dakota, the case cited most frequently.

Quill left room for Congress to act, which indeed it is doing with the Market Fairness Act. The impetus for the act has nothing to with the catalogue business, however. Rather, it’s the estimated $200 billion in annual Internet retail sales, a significant portion of which escapes taxation, that’s got the states pushing Congress to take a sledgehammer to a fundamental U.S. tax principle that has served the purpose of interstate commerce since 1787.

That year, of course, is when the U.S. Constitution replaced the Articles of Confederation. One of the flaws of the Articles was that it permitted each of the states to tax residents of others. Rather than get the budding nation closer to the nominal goal of confederation, it was endangering the expansion of vital post-colonial commerce by creating 13 tax fiefdoms and protectorates. The authors of the Constitution wisely addressed this by vesting the regulation of interstate commerce in the federal government.

That’s why the Marketplace Fairness Act is so troublesome. While indeed Congress has the power to create an state-to-state tax structure, it may be imprudent to do so. In seeking to close what it disingenuously calls a “loophole” that allows Internet sales to remain tax-free, it bulldozes a vital element of commerce law that protects consumers from taxation from other jurisdictions.

And that protection is as necessary as ever. As the Tax Foundation’s Joseph Henchman will remind Congress today in his testimony, states have every incentive to shift tax burdens from their own residents to others elsewhere. As an example, take all those taxes attached to hotel and car rental bills.

The Marketplace Fairness Bill puts great stock in the idea that software and technology can relived the “burden” that, according to the courts, state and local tax compliance places on out-of-state business. But even sales tax complexity can’t be solved with the literal click of the mouse. It’s more than just the 9,600 sales tax jurisdictions that need to be factored in. Tax rules differ state to state, city to city and town to town. Sometimes a candy bar is taxed, sometimes it’s not. Every August, some states declare a “sales tax holiday weekend” in hopes of boosting back-to-school business. Dates can vary. Bottom line, there’s no reliable plug-and-play software for this. Overstock.com chairman and CEO Patrick Byrne has said it cost his company $300,000 and months of man-hours to create a solution.

The Marketplace Fairness Bill takes tax policy in the wrong direction, setting up a classic slippery slope that will see states becoming more and more predatory. What’s needed instead is an alternative that respects both state’s rights and the limits set by the Constitution.

But there will be no real progress until state legislators admit what they are trying to do: collect more taxes. That at least makes the dialogue honest. Then the question becomes whether the initiative is necessary to begin with. After that, more reasonable constructs include an origin-based tax system, building on the framework that exists today. When I purchase an item in Sugar Land, Tex, I pay sales tax to Texas and Sugar Land. When I travel to Los Angeles and buy a souvenir from the Universal Studios tour, I pat sales taxes levied there. A more sensible tax structure allows merchants to comply with the tax rules in their own states.

The only objection comes from legislators in high sales tax states who complain origin-based taxation gives businesses that locate in states such as Oregon and New Hampshire, two of five that charge no sales tax, an advantage. My affable reply is “Why yes, it does. Doesn’t it?.”

A low-tax policy is one way states can compete constructively for commerce and economic growth. Consumers and businesses would be much better off if states looked at e-commerce as an opportunity to boost their economies by welcoming Internet enterprises instead of treating them, and their customers, as just another cash pump.

For more, See “About that Sales Tax ‘Loophole’”

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower