Adam Thierer's Blog, page 164

October 14, 2010

Of Set-Top Box Industrial Policies & Self-Serving Interests

If you want another prime example of how self-serving Washington interests often seek to wield the stick of Big Government to their advantage, look no further than the effort the FCC is currently undertaking to extend its "CableCARD" set-top box industrial policy. The regulatory shenanigans here got started 14 years ago with Section 629 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which included authority for the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to meddle in the video equipment marketplace. The FCC used that authority to impose a variety rules on the cable TV industry, such as CableCARD mandates, in the name of expanding device competition and consumer choice. Those regulations haven't done much other than impose added costs on consumers for very little corresponding benefit. And whatever growth we've seen in the market for video devices and services has been more organic and unplanned, and it has come from unexpected quarters (think of Apple and Google's TV efforts, and television distribution via video game platforms). Nonetheless, the FCC plowed forward today with additional layers of red tape in the hope of extending the CableCARD regulatory regime.

The Consumer Electronics Association (CEA) has long served as the prime cheerleader for this high-tech industrial policy since it would hobble video providers and benefit some of CEA's members in the process. Indeed, to read through the CEA's filings on this matter through the years, one is led to believe that CEA views cable systems as a sort of essential facility to which access must be granted in the name of preserving innovation by consumer electronics companies. With the CableCARD mandates, therefore, CEA is asking the FCC to impose a light form of common carrier regulation on the cable industry becuase that would help their interests in the end, regardless of what it meant for innovation at the core of networks.

Now, don't get me wrong. There are plenty of self-serving people and organizations around Washington. Let's face it, screwing over your competitors with regulation is what makes the "parasite economy" inside the Beltway tick! But what I find so interesting about this case study is how CEA has vociferously opposed (quite rightly, in my opinion) so many other high-tech industrial policies — the V-Chip, the so-called "broadcast flag," HDTV tuner mandates, proposals to embed FM tuners in cell phones, and so on — and yet they wholeheartedly endorse the CableCARD industrial policy because the consumer electronics industry would benefit from this particular industrial policy. Sadly, it's just another example of what Milton Friedman once called the "Business Community's Suicidal Impulse": the persistent propensity to persecute one's competitors using regulation or the threat thereof.

Nobody said capitalists were consistent, folks. It's capitalism for me, but not for thee.

Bill Shock Shouldn't Be a Federal Issue

The FCC proposed new rules today aimed at combating wireless "bill shock," a term that describes mobile subscribers getting hit with overage charges they didn't anticipate. The proposed rules would require wireless providers to create a system for alerting customers when they are about to incur extra usage charges for voice, text, data, or roaming.

I can certainly see why some consumers may be frustrated with wireless pricing practices. But this frustration hardly constitutes evidence that the mobile marketplace is actually failing. Yes, mobile carriers sometimes make mistakes, and they probably need to do more to ensure their customers understand how overage charges work.

Competitive forces, however, are far better equipped than federal regulators to punish providers that engage in genuinely harmful practices. And if the federal government must "do something" about bill shock, educating mobile subscribers about where to locate and track their usage information is a far better approach than prescriptive, burdensome federal regulation.

Hypocritically, even as the FCC tries to reign in bill shock, its own policies are harming consumers far more than any wireless industry practices. The FCC has again and again put off spectrum auctions that would enable mobile providers to offer better services at lower prices. As a result, consumers are suffering to the tune of billions of dollars each year. Economists Thomas Hazlett and Roberto Munoz published a study last year in which they concluded that U.S. wireless prices would decline by 8% if the FCC were to allocate an additional 60mhz of spectrum to mobile telephony.

If the FCC truly cares about wireless subscribers, rather than simply grandstanding against competitive (if imperfect) mobile carriers, the Commission's top priority should be to aggressively free up the airwaves.

But analysts at the Competitive Enterprise Institute urged the FCC not to interfere with market disputes and to instead turn its focus to the real obstacle to the wireless marketplace – the FCC's own anti-consumer approach to spectrum allocation.

"Educating mobile subscribers about where to locate their up-to-date usage information – which all major wireless providers make available – is a far better solution to 'bill shock' than prescriptive federal regulation," argued Ryan Radia, CEI Associate Director of Technology Studies.

Radia pointed out that some consumers' frustration with current wireless pricing practices is hardly evidence that the mobile marketplace is failing. "To be sure, mobile carriers make occasional mistakes, and they need to work harder to ensure their customers stay well-informed," Radia said. "But competitive forces are far better equipped than federal regulators to punish providers that engage in genuinely harmful practices or fail to satisfy consumers' evolving preferences."

In its efforts to address wireless bill disputes, the FCC purports to represent consumers' interests; yet, Radia argued, the agency is harming consumers by delaying action to free up radio spectrum — the lifeblood of wireless communications.

"Consumers are suffering to the tune of billions of dollars each year on account of the FCC's failure to free up radio spectrum for mobile communications," Radia said. "Economists Thomas Hazlett and Roberto Munoz recently published a study finding that U.S. wireless prices would decline by 8% if the FCC were to allocate an additional 60mhz of spectrum to mobile telephony."

"If the FCC genuinely cares about wireless subscribers, it should focus on aggressively freeing up the airwaves instead of comparatively trivial issues like bill shock."

Advocates of Regulation are to Charlie Brown as Washington, D.C., is to Lucy

This morning on WNYC in New York City, I debated Josh Silver of the pro-Internet-regulation group Free Press. It was a healthy exchange of views, except for a few barbs and innuendos thrown by Silver, who is obviously frustrated by his group's lack of progress in seeking a "government takeover of the Internet." (He wanted to debate in simple, ideological terms like that, so I indulge here.)

What was most interesting to me was how unsophisticated Silver is with respect to government and regulation. Take a look at his plea:

What we're asking for—what we need are regulatory agencies that are not captured by industry and that actually act on behalf of the American public. And that's what they were created to do. The FCC—1934, with the advent of radio—was created to make sure that the public interest was protected. And what we've seen is industry capture of regulatory agencies has made those agencies fail again and again and again.

And the only thing that's gonna work is if the Obama administration and the FCC stand up and say, "No more business as usual. We are going to protect net neutrality. We're going to protect competition, and make sure there's choices for consumers. And we're going to end the status quo in Washington that has really broken our entire political system."

The Obama administration and the FCC did stand up and say "no more business as usual," but that's what politicians do to seduce voters. Then, once in power, they go about business as usual. Lucy always yanks away the football, Charlie Brown.

Silver is not alone in having these sweet, sad "good government" sentiments. Many of my interlocutors, with whom I often share outcome goals, believe strongly in achieving those goals by remaking governmental and political systems so that they finally "work." They believe so strongly in this approach that they seem to think it's just around the corner—if only we prohibit some speech here, some petitioning of the government there. Y'know, "take the money out of politics."

Hopefully this fantasy will never come true, because it requires reversing fundamental rights such as free speech in all its instantiations—a handover of power from people to the government and elites that run it.

In the absence of that perfected, all-powerful government—thank heavens—we must organize the society's resources using the best machine we've got for discovering consumers' interests and delivering on them: an unhampered marketplace, now energized and enhanced by the Internet.

Milton Mueller's new book, Networks and States, is out

Although I won't be able to get around to penning a formal review of it for a couple more weeks, I was excited to get a copy of Milton Mueller's new book, Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance, in the mail today. I looks like a terrific treatment of some important cyberlaw issues. Here's the summary:

Although I won't be able to get around to penning a formal review of it for a couple more weeks, I was excited to get a copy of Milton Mueller's new book, Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance, in the mail today. I looks like a terrific treatment of some important cyberlaw issues. Here's the summary:

Mueller identifies four areas of conflict and coordination that are generating a global politics of Internet governance: intellectual property, cyber-security, content regulation, and the control of critical Internet resources (domain names and IP addresses). He investigates how recent theories about networked governance and peer production can be applied to the Internet, offers case studies that illustrate the Internet's unique governance problems, and charts the historical evolution of global Internet governance institutions, including the formation of a transnational policy network around the WSIS (World Summit on the Information Society).

As a fan of Net-related political taxonomies and philosophical paradigms, I couldn't help but quickly jump ahead to the very interesting concluding chapter on "Ideologies and Visions," in which Mueller examines "the political spectrum of Internet governance." There, on page 268, I was very excited to see this statement in his section on "Elements of Denationalized Liberalism":

Cyber-libertarianism is not dead; it was never really born. It was more a prophetic vision than an ideology or "ism" with a political and institutional program. It is now clear, however, that in considering the political alternatives and ideological dilemmas posed by the global Internet we can't really do without it, or something like it. That primal vision flagged two fundamental problems that still pervade most discussions of Internet governance: (1) the issues of who should be "sovereign" — the people interacting via the Internet or the territorial states constructed by earlier populations in complete ignorance of the capabilities of networked computers; and (2) the degree to which the classical liberal precepts of freedom get translated into the context of converged media, ubiquitous networks, and automated information processing.

Amen, brother! As a devoted cyber-libertarian myself, I can't tell you how excited I was to hear Mueller make that case. I look forward to tearing through the entire tract right after I finish a couple of other books.

Incidentally, Mueller, who is a Professor at Syracuse University's School of Information Studies, also penned a terrific book on ICANN and global Internet governance issues back in 2002: Ruling the Root: Internet Governance and the Taming of Cyberspace. At the time, I hosted a Cato event for him and you can still find a grainy old Real Player video of it here. I'm shocked by how much less gray hair Milton, Harold Feld, and I had just 8 years ago!

A Comment on Tim Wu's Critique of Sunstein's Internet "Fragmentation" Thesis

I'm preparing what will become another one of my absurdly long and boring book reviews and this time it's Tim Wu's new book — The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires — that will be under the microscope. As with many of the books I review, I'm going to go pretty hard on it, especially since I disagree with Tim on so many fronts. But I appreciate his willingness to engage a kooky libertarian like me and the fact that he shared an early proof of the book with me so I could prepare a review.

I'm preparing what will become another one of my absurdly long and boring book reviews and this time it's Tim Wu's new book — The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires — that will be under the microscope. As with many of the books I review, I'm going to go pretty hard on it, especially since I disagree with Tim on so many fronts. But I appreciate his willingness to engage a kooky libertarian like me and the fact that he shared an early proof of the book with me so I could prepare a review.

Nonetheless, I figured I would pre-empt the pain to come by posting a short comment here about one portion of the book with which I find myself in violent agreement. Chapter 16 of Wu's book is a short history of cable television and it includes a brief discussion of a favorite theory of many Internet pessimists: the notion that the increased personalization or customization that Internet brings us will lead to a variety of potential ills, including: homogenization, close-mindedness, an online echo-chamber, information overload, or corporate brainwashing. Their greatest fear seems to be that hyper-customization of websites and online technologies will cause extreme social "fragmentation," "polarization," "balkanization," "extremism" and even the supposed decline of deliberative democracy.

Nonetheless, I figured I would pre-empt the pain to come by posting a short comment here about one portion of the book with which I find myself in violent agreement. Chapter 16 of Wu's book is a short history of cable television and it includes a brief discussion of a favorite theory of many Internet pessimists: the notion that the increased personalization or customization that Internet brings us will lead to a variety of potential ills, including: homogenization, close-mindedness, an online echo-chamber, information overload, or corporate brainwashing. Their greatest fear seems to be that hyper-customization of websites and online technologies will cause extreme social "fragmentation," "polarization," "balkanization," "extremism" and even the supposed decline of deliberative democracy.

These concerns were first given widespread circulation by the prolific University of Chicago law professor Cass Sunstein in his 2001 book Republic.com. In that book, Sunstein raised deep reservations about what Nicholas Negroponte had first called "The Daily Me" of media customization that the Internet and digital communications allows. Sunstein referred to "The Daily Me" in contemptuous terms, saying that the hyper-customization of websites and online technologies was causing extreme social fragmentation and isolation that could lead to political extremism. "A system of limitless individual choices, with respect to communications, is not necessarily in the interest of citizenship and self-government," he wrote. Sunstein was essentially claiming that the Internet is breeding a dangerous new creature: Anti-Democratic Man. "Group polarization is unquestionably occurring on the Internet," he proclaimed, and it is weakening what he called the "social glue" that binds society together and provides citizens with a common "group identity." If that continues unabated, Sunstein argued, the potential result could be nothing short of the death of deliberative democracy and the breakdown of the American system of government.

Other pessimists, like Andrew Keen, go further and claim that "the moral fabric of our society is being unraveled by Web 2.0. It seduces us into acting on or most deviant instincts and allows us to succumb to our most destructive vices. And if is corroding the values we share as a nation." (Keen, Cult of the Amateur, at 163.) Nick Carr summarizes the views of the pessimists when he says: "it's clear that two of the hopes most dear to the Internet optimists—that the Web will create a more bountiful culture and that it will promote greater harmony and understanding—should be treated with skepticism. Cultural impoverishment and social fragmentation seem equally likely outcomes." (Carr, The Big Switch, at 167.)

In sociological literature and the field of media criticism, this concern is sometimes referred to as "the water cooler" or "social campfire" problem. In the critics' Norman Rockwell-esque interpretation of the age of mass media, we all gathered around the water cooler at work each day, or the proverbial campfire during the weekend, and shared common stories and feelings that we had experienced in newspapers and magazines, or on radio or television. This supposedly created a more tightly-knit national "community" and encouraged greater empathy and social understanding among the citizenry. And this is what is now being decimated by the more personalized, atomistic Internet era, the critics say.

Tim Wu takes challenges these claims first by noting that "The age of 'mass media' upended by cable television was actually a period of unprecedented culture homogeneity." He continues:

In this sense, cable television's undoing of the mass, or national, media culture was merely the undoing of a transient twentieth-century invention. In the nineteenth century, as now, there was little common information for any two randomly selected American citizens to discuss, even if there had been a water cooler.

For the purposes of our narrative, the conclusion is clear: an open medium has much to recommend it, but not the power to unify the country. For a fully united national community, nothing succeeds like centralized mass media, a fact not lost on the Fascist and Communist totalitarianisms. With an open medium, one has diversity or fragmentation of content, and with it, differences among groups and individuals are accentuated rather than elided or repressed. (p. 214-15)

Quite right, and Wu could have gone on to make a more cogent point: Isn't it just as good that we all have something new and unique to discuss around the water cooler each day! I mean, seriously, think about the shallowness of the Sunstein critique for a moment. He and other pessimists are essentially saying that we were better off in an era when, if we all weren't home sitting in front of our TV sets at exactly 6:30 each night, then we missed our chance to hear the same three old white guys in bad suits tells us what the important news of the day was! Look, I liked Cronkite, Brinkley & Co., but I will take today's 24/7 news cycle of instantaneous news and information over that old system any day of the week.

And what about that "fragmentation" / "polarization" claim that Sunstein and other pessimists make? Well, last time I checked, mobs weren't rioting in the streets or rushing out to join the Nazi or Communist parties! Those knuckleheads still exist, of course, but they have always existed. And let's not forget, as Tim Wu apty noted, it was during the age of scarcity and mass media that those movements gained traction and took control in some countries. In the Internet Age, by contrast, such extremist lunatics usually get exposed and widely ridiculed. As the old saying goes, the answer to bad speech is more speech. The Internet has given us a platform to do so and helped us counter such societal extremism, even if it has simultaneously given such extremists a new soapbox to stand on and spew their hatred and stupidity. Let them spew it and we will respond! And we will marginalize them in the process.

Interestingly, some scholars are starting to take on Sunstein's fragmentation thesis using more formal statistical methods. A recent study by Matthew Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business found "no evidence that the Internet is becoming more segregated over time" or leading to increased polarization as Sunstein and other pessimists fear. Instead, their findings show that the Net has encouraged more ideological integration and is driving us to experience new, unanticipated viewpoints. As New Your Times columnist David Brooks noted, "This study suggests that Internet users are a bunch of ideological Jack Kerouacs. They're not burrowing down into comforting nests. They're cruising far and wide looking for adventure, information, combat and arousal."

Thus, I agree with Tim Wu that we have reasons to be optimistic about the benefits of the more diverse, heterogeneous world we live in today. Sure, we have lost something in the process. Namely, we've lost an abundance of those "mega-moments" in media when 80+ percent of us would gather around the boob tube to watch Elvis or the Beatles on "The Ed Sullivan Show," or the series finale of "M.A.S.H." But you know what, I think many of us would have rather been watching or doing something else, anyway. And now we can. We're not going to become a bunch of knuckle-dragging social neanderthals because we do.

October 13, 2010

Privacy Polls & Real-World Trade-Offs Revisited

By Berin Szoka & Adam Thierer

Last Friday, Common Sense Media (CSM) held an event (video) at the National Press Club featuring the chairmen of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The regulatory activist group released a new poll on children and privacy (Exec Summary & Full Survey). Unfortunately, like almost every other privacy-related poll, theirs is more geared towards fueling a privacy panic than on exploring the real-world trade-offs between legislating "greater privacy" (a hopelessly abstract concept in most conversations) and losing the consumer benefits of data sharing: innovation in online services and the quality and quantity of services and content supported by data-driven advertising.

What better way to drum up Congressional support for paternalistic privacy legislation (restrictions on online data use) than by asserting that this is what the electorate already wants? The poll asks whether "Congress should update laws that relate to online privacy and security for children and teens." Three-fifths (61% of parents, 62% of adults) said yes. But earlier in the survey, only 16% knew that the Children Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 already prohibits "online companies… from collecting or using personal information from children under the age of thirteen without a parent's permission." (53% weren't sure.) If parents don't know what Congress has already done, how meaningful is it for them to say they think Congress needs to do more? (There's a reason we don't have direct democracy.)

Indeed, how useful are such polls, anyway? Ultimately, what such polls really tell us is that, if you ask parents—or adults in general—whether they're concerned about protecting kids, of course most will say yes, because nobody wants to think of themselves as the kind of person who doesn't care about kids.

This bias becomes even more problematic when the choice at issue involves such stark trade-offs—especially when we're talking about throwing a wrench (restrictions on data use and collection) in the economic engine that has again and again provided funding for media and services that users just won't pay for. As we've noted here before, privacy polls and surveys reveal only what the public will tell pollsters in response to the particular questions asked. On privacy, those questions are almost invariably designed to solicit responses suggesting an urgent need for more laws and government action. Even the fairest of these surveys is no substitute for real-world experiments in which people make real choices, in real time, often with real money, and face many real trade-offs.

What this debate comes down to is the unarticulated trade-off between the benefits of receiving tailored (relevant!) ads and the costs of that tailoring. Yet, too often, policymakers and even the public seem oblivious to that trade-off. There's too much "assume-a-platform" thinking going on out there: CSM and their ilk imagine all these free online sites and services we and our children enjoy today just fall like manna from heaven—and will keep working no matter how they're hamstrung. Worse yet, discussions about "harms" take place at such a level of abstraction as to be almost meaningless.

For example, during Friday's press conference announcing the poll results, Common Sense Media founder and CEO Jim Steyer pushed hard for aggressive Internet regulation to "protect privacy"—yet for all his adamance, he couldn't identify a single clear harm demanding further government intervention. (He barely mentioned existing regulation, like the FTC's enforcement of corporate promises or the Fair Credit Reporting Act, which restricts the use of personal data for credit decisions, where a real harm could occur to users.)

Steyer actually asserted—repeatedly—that regulation will not burden online operators, and blithely suggested that, in essence, if dot-com entrepreneurs are smart enough to build all these cool sites and services, they can also figure out how to craft or live with new rules for how the Internet economy should work. Ah, yes… everything will be just fine and dandy once the regulatory wrecking ball comes and requires every online site that currently uses advertising—powered by data collection—to completely change the way they do business and find new business models that involve getting someone other than advertisers to pay for all that free stuff. More on that Beltwayland fantasy in a minute!

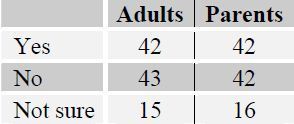

First, however, CSM deserves some credit for at least asking respondents two survey questions that gets to the heart of our concern about trade-offs. Specifically, survey question #14 asked, "Some social networks and search engines that offer online services for free say they can only do so by selling advertising tailored to user habits and interests. Do you believe this is true?" Of course, that statement is obviously true: There's no such thing as a free lunch. Something has to pay for all theses services; that something is advertising and marketing techniques that are powered by data aggregation about users' apparent interests. Regardless, CSM left the question open-ended, either becuase they don't buy that notion or they wanted to suggest to respondents that it's actually an open question (as if site operators are just lying about having to pay their bills somehow!) Responses split almost perfectly:

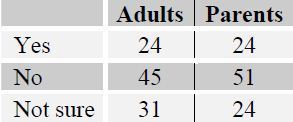

Importantly, however, in the next question, CSM asked: "Would you prefer to pay for services currently provided for free on search engines and social networking sites in lieu of having information about you sold to advertisers?" Nearly half (45%) of all adults and, surprisingly, an even higher (51%) proportion of parents, said they would not prefer to pay for services but instead continue to allow data collection / advertising to fund online content and services.

Interestingly, CSM never mentions these important findings in their press release or online summary of the poll. Instead, they play up survey results suggesting that plenty of people, especially parents, have general concerns about privacy. Well, of course they do! That's like asking if you have general concerns about the flu or (if you live in Florida) hurricanes. But, again, there has to be some context and some acknowledgment of the fact that the world is full of trade-offs and that regulation has consequences. Regrettably, but perhaps unsurprisingly, CSM downplays the questions in their survey that speak to this. It's one of the rare instances of trade-offs even being mentioned in a privacy poll, probably because those who generally conduct privacy polls had political motivations: They want federal privacy regulation and, therefore, they selectively ask only leading questions about generic privacy concerns that are always going to produce lop-sided results.

We applaud CSM for breaking with that unfortunate tradition—the polling equivalent of "stuffing the ballot box"—and at least asking people if they understand there's a trade-off here and whether they'd be willing to pick up the full freight of what the online services and content they consume actually cost. Of course, once CSM heard that, when faced with that stark choice, the majority of people would not want to pay, the organization decided to essentially bury that result and instead highlight the other "Do you love your mother?" sort of questions that produce predictable results precisely because they are consequence-free. (Perhaps they only included these questions because they know we've been so relentless in our criticism of previous polls for failing to ask any questions even approximating trade-offs?)

What's even more concerning about the way CSM chose to play these poll result is the shameless scare tactics Jim Steyer used during the press conference. At one point, he compared these privacy concerns to "tainted meat" and unregulated meatpackers! You know, because people are dying left and right from "consuming" unregulated web content. This analogy is nothing less than insulting to web entrepreneurs, those who use them, and the policymakers Steyer is grandstanding for.

The fantasy-land mentality continued when Steyer said CSM wants someone in the Internet industry to develop some sort of "eraser button" to wipe out portions of our online pasts. "We can't tell you how to do that," Steyer said, but the onus is on industry to do it—and he expects them to get on it immediately. Right… perhaps the Internet's Director of Operations can issue all companies and consumers one of those Staples "EASY" buttons for their desks, except this one would just say "ERASE" and magically clean up our online pasts! Again, this is consequence-free thinking at work and it is dangerous—especially to smaller website operators who just can't absorb endless regulatory mandates without suffering profound consequences.

Speaking of scare tactics, it's quite revealing that CSM chose to phrase Question #2 as follows: "Of the following, which do you feel is the main reason you are concerned about children revealing personal information online?" And then they listed a few possible responses with the first being "sexual predators." Nothing like fanning the flames of moral panic by asking about child predation! CSM has certainly studied the literature closely enough to know how completely out of proportion this concern has been blown. Read the final report of the Harvard Berkman Center "Enhancing Child Safety" blue ribbon task force to get the definitive word on that.

But it's equally interesting that, despite all the hand-wringing at Friday's press conference about targeted marketing, only 4% of respondents to this poll felt product marketing was the primary concern relating to collection of information about children online. Nonetheless, CSM is still demanding more regulation in the name of protecting kids from some amorphous corporate bogeyman. Complicating matters is the fact that, during the press conference, Jim Steyer said that for CSM, a "kid" is anyone under 18. This was consistent with comments that CSM submitted to the FTC in July as part of the agency's review of the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), CSM advocated not just expanded educational efforts, which we applaud, but also expanding COPPA's age scope to cover all kids under 18 as well as opt-in mandates for the collection and use of any "personal information" or "behavioral marketing."

Incidentally, during Friday's press conference, a sharp audience member asked how, exactly, government or websites would go about differentiating kids from adults for purposes of expanded "kids' privacy" regulation. Good question!—and one that Steyer promptly ignored. He went silent at that point, perhaps recognizing that CSM was wading into the unconstitutional waters of COPA-like age verification mandates for the Internet without the slightest clue of the real-world implementation of their proposals. FTC Chairman Jon Leibowitz jumped in to suggest that it could be done because marketers already know how to track kids and have sophisticated techniques to figure out who is who and what age they are. But that's simply not true.

The reality, as we have noted here before many times [see 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] is that there is no easy way to verify the ages of kids online becuase they lack the sort of credentialing records (driver's licenses, credit cards, tax records, home mortgages, work or military records, etc) that adults possess. Thus, if you say you want to verify kids' ages online, what you are really saying is that you want to verify adults online. Again, this gets us right back into the thorny COPA world which has already been litigated to the hilt and found unconstitutional many times over because of the free speech and privacy issues it raises to create the equivalent of an online "show-us-your-papers" regulatory regime.

We object to other CSM proposals, including their call for new laws and regulations that deny any ability to serve up targeted ads and opt-in mandates for geo-location and changes of personal information, and their call for "independent privacy ratings," which seems to echo their old call for "universal ratings" for all media content. But we haven't seen all the details on those, so we'll have to address them later.

What is clear, though, is that Common Sense Media is back on the regulatory warpath, again advocating comprehensive regulation of the Internet in the name of "protecting the children." We can certainly join hands with CSM in their call for more education on all these issues, and we can also live with the FTC holding companies to the promises or claims they make when it comes to the personal information they collect and what they do with it. But what Common Sense Media is asking here is for the Internet to be re-engineered through a sweeping regulatory regime that could decimate the "free" and open Internet as we know it. That's what this battle is all about.

_____________

Additional Reading:

Joint CDT-PFF-EFF Comments on FTC's COPPA Review & the Dangers of COPPA Expansion

"Privacy Polls v. Real-World Trade-Offs" – by Berin Szoka

"Comments at FTC Workshop Panel on Privacy Polls & Surveys" – by Adam Thierer

"Troubling COPPA Filing by Common Sense Media" – by Adam Thierer

"COPPA 2.0: The New Battle over Privacy, Age Verification, Online Safety & Free Speech" – by Berin Szoka & Adam Thierer

"Privacy Trade-Offs: How Further Regulation Could Diminish Consumer Choice, Raise Prices, Quash Digital Innovation & Curtail Free Speech" – by Berin Szoka, (Comments to the Federal Trade Commission at the Privacy Roundtables, Nov. 10, 2009)

In the Lull of Election Year Politics, Internet Ads Self-Regulation Has a Fighting Chance

Earlier this month, a coalition of ad and marketing associations made public a new self-regulatory program for behavioral advertising (or as we like to refer to them, "interest-based ads"). Will it be enough to whet the appetite of members of Congress waiting to chomp on the privacy bit when they get back in November?

Earlier this month, a coalition of ad and marketing associations made public a new self-regulatory program for behavioral advertising (or as we like to refer to them, "interest-based ads"). Will it be enough to whet the appetite of members of Congress waiting to chomp on the privacy bit when they get back in November?

Hopefully. But it all depends on ad network uptake and user adoption. FTC Chairman Jon Leibowitz's wait-and-see attitude toward the self-regulatory effort probably sums up the thoughts of many pro-regulatory privacy advocates. According to Politico's Morning Tech, Leibowitz said:

We commend industry's effort to get a broad group of industry leaders on board. However, the effectiveness of this effort will depend on how, and the extent to which, the opt-out is actually implemented and enforced – all of which is yet to be seen. We also urge industry to make sure that the opt-out is easy for consumers to find, use, and understand.

Making it easy for consumers is what the advertising option icon (above) is all about. It's a just-in-time "heads-up" accompanying ads that allows users to obtain more information about why they're seeing the ad. In the future, it will allow users to opt-out. Ad networks will pay a license fee to have the right to display the icon and must submit to ongoing compliance.

It's the compliance part that's interesting. The Better Advertising project is a new company formed specifically for the self-regulatory program. According to Internet Retailer, "the Council of Better Business Bureaus and the Direct Marketing Association, a trade group for direct-to-consumer marketers and retailers, will begin monitoring compliance with the program early next year."

Let's hope the coalition moves quickly and successfully, before Congress does….

Schneier on Facebook: Factually Incorrect

The Register quotes security guru Bruce Schneier saying: "Facebook is the worst [privacy] offender – not because it's evil but because its market is selling user data to its commercial partners."

Facebook's business model is to guide advertisements on its site toward users based on their interests as revealed by data about them. It is not to sell data about users. Selling data about users would undercut its advertising business.

It's easy to misspeak in extemporaneous comments, and The Register is not your most careful media outlet. But we've almost got enough data points to show a consistent practice of misrepresentation on Bruce Schneier's part. Perhaps that should be actionable as an unfair or deceptive practice under section five of the FTC Act.

October 12, 2010

DIY News and Commentary

What a delight it has been to watch the rescue of the Chilean miners on a live feed, without commentary from any plasticized, blathering "news reporter." Of course, there are editorial judgments being made by the camera crews and on-scene director, but it is refreshing to make my own judgments based on what I see happening and what I see on the faces of the miners, their wives, and standers-by.

As my friend, the curmudgeonly @derekahunter notes, "There's really nothing worse than listening to a reporter attempting to fill time while waiting for something to happen."

Meanwhile, I've been chasing down some intemperate commentary on Twitter about the recent discovery of explosives in a New York cemetery. One Fred Burton, identified on his Twitter feed as Vice President of Intelligence for STRATFOR and a former counter-terrorism agent, Tweeted at the time that these explosives seemed like "a classic dead drop intended for an operative."

But now we know the explosives are old, they were dug up and laid aside in May or June of 2009, and someone recently found them and decided to report them. That is not consistent with a dead drop, and Burton was wrong to speculate as he did, starting an Internet rumor that needlessly propagates fear.

As a public service, I'm doing a little bit to cut into Burton's credibility, which should cause him to think twice next time. The winning Tweet is not mine, though. It's @badbanana's: "Military-grade explosives found at NYC cemetery. Hundreds confirmed dead."

In summary, it's a do-it-yourself news and commentary night. I'm making my world and re-making yours (just a tiny bit), rather than all of us sitting around being fed what to think.

What Privacy Conservatives & Moral Conservatives Share in Common

In a post here last month on "Two Paradoxes of Privacy Regulation," I discussed some of the interesting — and to me, troubling — similarities between rising calls for online privacy regulation and ongoing attempts to enact various types of controls on online speech or expression. In that essay, I argued that while most privacy advocates are First Amendment supporters as it pertains to content regulation, they abandon their free speech values and corresponding constitutional tests when it comes to privacy regulation. When the topic of debate shifts from concerns about potentially objectionable content to the free movement of personal information, personal responsibility and self-regulation become the last option, not the first. Privacy advocates typically ignore, downplay, or denigrate user-empowerment tools, even though many of those same advocates endorse "self-help" efforts as the superior method of dealing with objectionable speech or media content. In essence, therefore, they are claiming self-help is the right answer in one context, but not the other. Ironically, therefore, privacy advocates and moral conservatives actually share much in common in that they are using the same playbook to advance their goals: They are rejecting personal responsibility and user-empowerment tools and techniques in favor or government control for their respective issues.

Keeping that insight in mind, I want to take this comparison a step further and suggest that what really unites these two movements is a general conservatism about how our online lives and online business should be governed. For the moral conservatives, that instinct is well-understood. They want hold the line against what they believe is a decaying moral order by restricting access to potentially objectionable speech or content — dirty words, violent video games, online porn, or whatever else. The conservatism of the modern privacy movement is less obvious at first blush. I suspect that many privacy conservatives would not consider themselves "conservative" at all, and they might even be highly offended at being grouped in with moral conservatives who seek to wield government power to control online speech and expression. Nonetheless, the two groups share a common trait — an innate hostility to the impact of technological / social change within the realm of "rights" or values they care about. In their respective arenas, they both rejected the evolutionary dynamism of the free marketplace and they long for a return to a simpler and supposedly better time.

For the privacy conservatives, we see this instinct on display in discussions about "targeted advertising" and "behavioral marketing." Most privacy regulation advocates want to slow or stop the advancement of online advertising techniques for a variety of reasons. Some say privacy — however they define it — is an inalienable human right and that data collection and targeted marketing betrays "human dignity." Others just despise commercialism and advertising in all its forms and hope to take steps to stop its spread or evolution. Still others say they want regulation to help give users more control over their personal information. Or, some combination of all of the above factors motivates their desire to see advertising and marketing practices curtailed.

On Defining Harm

Privacy conservatives and moral conservatives share another common trait: The struggle to identify or prove a tangible harm exists that justifies government regulation that would foreclose the evolution or markets and/or speech. "Privacy" has long been a controversial, ambiguous term, much like the terms "obscenity" or "indecency" in the speech context. My response in both cases is not that "harm" never exists, but rather that:

"harm" is extremely user-specific;

such "harms" should not necessarily be elevated to actionable legal / regulatory matters; especially when..

the better approach is user-empowerment and personal responsibility instead of collectivized political responsibility for such matters.

Stated differently, precisely because of the eye-of-the-beholder problem we face in both speech and privacy contexts, I believe the better approach is to rely on "household standards" (user-level controls + personal responsibility) instead of "community standards" (government regulation for the entire universe of consumers / users). Thus, in light of the diverse nature of the citizenry and the importance of the evolution of online markets and speech, freedom should generally trump control.

Journalism provides a good case study for why that should be the general rule. When it comes to the concerns about what should or should not be aired or reported by journalists, most of us would come down in favor of press freedoms and greater freedom of speech. We don't allow concerns about violent media images or salty language to trump the rights of journalists to report on wars, for example. In a similar sense, we don't allow privacy rights to trump freedom of speech as it relates to the collection of private facts about individuals by journalists. Think about it; the job of a good journalist is to be a nosy son-of-a-bitch. They pry into every corner of the private lives of individuals. They not only get paid to do, but they win awards for doing it well! The First Amendment generally protects their ability to gather and reveal all this information about individuals and organizations. Again, speech rights trump privacy rights. That isn't always the case, of course, but it is 9 times out of 10. So, for purposes of our discussion here, the interesting question is: How far would privacy conservatives be willing to go to undermine speech rights since — if enforced aggressively — a privacy "right" would essentially become "a right to stop people from speaking about you" (to borrow the memorable subtitle of a 2000 Eugene Volokh law review article)?

The Case for Transparency, and the Futility of It

Like moral conservatives, privacy conservatives are on their strongest footing in advocating greater transparency. Before jumping to direct government regulation of speech or content, some moral conservatives are willing to give greater transparency a shot. For example, they push for content creators to reveal more details about the nature of their products using labels or ratings so that consumers can better understand what they will see or hear. Similarly, before advocating comprehensive Internet regulation, some privacy conservatives at least give lip service to the idea of industry self-regulation and they encourage sites and services to be more transparent about the information they collect about users for advertising / marketing purposes.

Such transparency generally doesn't restrict innovation and progress. In fact, in some ways, it can help create a more vibrant market if consumers act upon the information they are given. However, whether we are talking about objectionable media content or privacy-related matters, it doesn't seem like many consumers are willing to do much to change their behavior once supplied with better product or service information — at least not in the way the regulatory advocates desire. In both cases, moral conservatives and privacy conservatives can't seem to come to grips with the fact that the world isn't made of people who share their hostile knee-jerk reaction to these things.

For example, there are some outstanding rating and labeling systems out there for movies and games, and those content descriptors really do give people (especially parents) a good idea of what they can expect to see, hear or play. But the existence of those ratings and labels doesn't deter millions upon millions of people from rushing to watch or buy a controversial new movie or video game that many moral conservatives probably find offensive. Same goes for language. We can warn people nasty talk is coming, or even channel it to later hours of the day, but a lot of people will still consume it anyway. Many people probably recoiled upon first hearing a George Carlin monologue back in the 70s. But while the moral conservatives couldn't get over it — and still enforce regulations based on one particularly famous Carlin monologue — the rest of the world moved on. In fact, in 2008, Carlin was awarded the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor as one of our country's most revered satarists. Society evolved not just to accept, but embrace, Carlin's wicked wit and even much of his billingsgate.

Similarly, privacy conservatives — who tend to think the multitudes share their general aversion to almost any form of data collection or commercial advertising — often seem mystified that the masses aren't in open revolt against the likes of Facebook, Google, or online advertising networks. To hear many privacy regulatory advocates talk, you'd think online advertising innovation should have been frozen in the pop-up ad era. Some of them still can't get over the fact that cookies weren't regulated out of existence a decade ago. Yet, despite their fundamentalist views about privacy rights and supposed violations of those rights, progress has marched on. Privacy expectations — much like cultural / speech expectations — have evolved. New baselines have emerged. And while there's an occasional flashpoint over something particularly inflammatory — for speech, think of the Janet Jackson incident or the Grand Theft Auto "Hot Coffee" incident; and for privacy, think Facebook Beacon and Google Buzz — the reality is that most people have adapted to technological and social change. Stated differently, regardless of what any poll or survey might suggest, citizens have generally rejected the fundamental conservatism of both the moral conservatives on content issues and the privacy conservatives on advertising / marketing issues.

Strange Bedfellow Alliances?

Are formal alliances between privacy conservatives and moral conservatives likely? I think they are possible, but highly unlikely. On occasion, some moral conservatives will reach across the aisle and work with Left-leaning groups when it works to their advantage. A prime example came back in 2003-04 during the media ownership reform debates, when social conservatives like Brent Bozell aligned the Parents Television Council with the radical regulatory group Free Press and its neo-Marxist founder Robert McChesney. Bozell's contempt for entertainment companies was so extreme that he was willing to make peace with extremists like Free Press, who are always happy to string up the capitalists in the content community.

But that's an unusual example. It's unlikely we'll see the extreme poles of moral and privacy conservatism making many alliances because they generally don't play well together. That is, most moral conservatives don't necessarily have a big beef with online advertisers, and few privacy conservatives care about free speech issues (and, to the extent they do care, they probably favor greater First Amendment freedoms).

However, whether they broker formal alliances or not, what should be clear is that moral conservatives and privacy conservatives are unwittingly working together as they both strive to bring greater government control to cyberspace and end evolutionary dynamism in their respective arenas.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower