Adam Thierer's Blog, page 163

October 20, 2010

What is the evidence for cybersecurity regulation?

I've been looking into the cybersecurity issue lately, and I finally took the time to do an in-depth read of the Securing Cyberspace for the 44th Presidency report, which is frequently cited as one of the soundest analyses of the issue. It was written by something of a self-appointed presidential transition commission called the "Commission on Cybersecurity for the 44th President," chaired by two congressmen and with a membership of notables from the IT industry, defense contractors, and academia, and sponsored by CSIS.

What I was struck by is the complete lack of any verifiable evidence to support the report's claim that "cybersecurity is now a major national security problem for the United states[.]" While it offers many assertions about the sorry state of security in government and private networks, the report advances no reviewable evidence to explain the scope or probability of the supposed threat. The implication seems to be that the authors are working from classified sources, but the "if you only knew what we know" argument from authority didn't work out for us in the run up to the Iraq war, and we should be wary of it now.

Now, while they may not say much about what exactly the threat is, they do tell us exactly how they'd like to fix it: "Regulate for Cyberspace," they say in a chapter heading. This includes mandatory security standards and mandatory authentication of identity using government-issued credentials for access to critical infrastructure. (Who gets to decide what counts as critical infrastructure?) The report asserts plainly:

It is undeniable that an appropriate level of cybersecurity cannot be achieved without regulation, as market forces alone will never provide the level of security necessary to achieve national security objectives.

But without any verifiable evidence of the threat, how are we to know what exactly is the "appropriate level of cybersecurity," and whether market forces are providing it? To its credit, the Commission recognizes that over-classification is a problem and recommends more information sharing. Until the public can see some evidence of a threat, and as long as less sober proponents of cybersecurity regulation and spending are using alarmist rhetoric to push their agenda, we should hope Congress takes it slow on the issue.

Bonus: The CSIS Commission is apparently very security conscious. The report, which is made available as a PDF, is somehow encrypted in a way that does not allow one to copy and paste or search within the document. You can copy, but when you try to paste you get garbage. Searching returns no results. Kinda not the way a free exchange of ideas happens online.

October 19, 2010

NGOs, Law Enforcement and Internet Companies –Coming Together to Fight Commercial Sexual Exploitation

Today I testified at a hearing by Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley on commercial sexual exploitation and the Internet. When I first learned about it, I feared the worst: time to demonize the Internet. After all, the hearing announcement openly targeted Craigslist and websites generally. But this was not the case at all—as we heard, NGOs, law enforcement, and industry all have roles to play.

Instead of Internet-bashing, the hearing was a constructive dialogue. We learned why children are forced into prostitution and how classified ads on the Internet can promote this illegal activity. I was there to learn how we can help.

Commercial sexual exploitation is big business. Over 100,000 women are in the illegal sex trade. Often these women are actually teenage girls, vulnerable and with no place to go. Their lives are run by pimps, they cater to "johns," and their lives are a living hell – except that these women become so desensitized that they eventually have no life at all.

These child prostitutes show up in advertisements for "escort services" or "adult services." Traditionally, these ads were in the yellow pages. Now they exist on the Internet, and these listings can often be graphic. But it's hard to tell whether these ads involve women against their will or underage girls. That's why there are folks who would like to see all these ads disappear. And they'll blame Internet classifieds—indeed, one witness called sites like Craigslist and Backpage "electronic pimps."

Unfortunately, there are those that think it is better to force the shut down of the adult services section of these sites. But as we heard from danah boyd of Microsoft and a fellow at the Harvard Berkman Center, merely shutting down the listed supply of adult services is superficial. It's shutting off the most visible aspect of human anti-trafficking, which is a huge honeypot where pimps advertise and johns congregate. This should be the first place to start an investigation, not end a prosecution.

It's far better for law enforcement to use these sites to identify what they think are ads of women in forced prostitution, and then infiltrate their criminal networks to reduce both the supply of women and the demand for their services. If we can develop strategies to break the networks, we can get to the root of the problem.

To this end, danah boyd also made great points about not getting distracted by the technology. Bad actors are sexually exploiting young girls by using the Internet to further their criminal enterprise, but it's not an Internet problem per se. Focusing on removing websites or portions of sites addresses symptoms of a much deeper criminal syndicate. For the most part, I think this point resonated with the Attorney General's staff.

What certainly resonated throughout the entire hearing was that sex trafficking is a complex problem that requires a multi-disciplinary approach. We heard this from child welfare and victimization groups, law enforcement, and the online industry.

And that's why we heard AG Coakley call for a task force to study the issue. We support her desire for all the interested groups to come together, and look forward to working with her to help eliminate commercial sexual exploitation.

Fox-Cablevision and the Net Neutrality Hammer

When the only thing you have is a hammer, as the old cliché goes, everything looks like a nail.

When the only thing you have is a hammer, as the old cliché goes, everything looks like a nail.

Net neutrality, as I first wrote in 2006, is a complicated issue at the accident-prone intersection of technology and policy. But some of its most determined—one might say desperate—proponents are increasingly anxious to simplify the problem into political slogans with no melody and sound bites with no nutritional value. Even as—perhaps precisely because—a "win-win-win" compromise seems imminent, the rhetorical excess is being amplified. The feedback is deafening.

In one of the most bizarre efforts yet to make everything about net neutrality, Public Knowledge issued several statements this week "condemning" Fox's decision to prohibit access to its online programming from Cablevision internet users. In doing so, the organization claims, Fox has committed "the grossest violations of the open Internet committed by a U.S. company."

This despite the fact that the open Internet rules (pick whatever version you like) apply only to Internet access providers. Indeed, the rules are understood principally as a protection for content providers. You know, like Fox.

OK, let's see how we got here.

The Fox-Cablevision Dispute

In response to a fee dispute between the two companies, Fox on Saturday pulled its programming from the Cablevision system, and blocked Cablevision internet users from accessing Fox programming on-line. Separately, Hulu.com (minority owned by Fox) enforced a similar restriction, hoping to stay "neutral" in the dispute. Despite the fact that "The Simpsons" and "Family Guy" weren't even on this weekend (pre-empted by some sports-related programming, I guess), the viewing public was incensed, journalists wrote, and Congress expressed alarm. The blackout, at least on cable, persists.

A wide range of commentators, including Free State Foundation's Randolph May, view the spat as further evidence of the obsolescence of the existing cable television regulatory regime. Among other oddities left over from the days when cable was the "community antenna" for areas that couldn't get over-the-air signals, cable providers are required to carry local programming without offering any competing content. But local providers are not obliged to make their content available to the cable operator, or even to negotiate.

As cable technology has flourished in both content and services, the relationship between providers and content producers has mutated into something strange and often unpleasant. Just today, Sen. John Kerry sent draft legislation to the FCC aimed at plugging some of the holes in the dyke. That, however, is a subject for another day.

Because somehow, Public Knowledge sees the Fox-Cablevision dispute as a failure of net neutrality. In one post, the organization "condemns" Fox for blocking Internet access to its content. "Blocking Web sites," according to the press release, "is totally out of bounds in a dispute like this." Another release called out Fox, which was said to have "committed what should be considered one of the grossest violations of the open Internet committed by a U.S. company."

The Open Internet means everything and nothing

What "open Internet" are they talking about? The one I'm familiar with, and the one that I thought was at the center of years of debate over federal policy, is one in which anyone who wants to can put up a website, register their domain name, and then can be located and viewed by anyone with an Internet connection.

In the long-running net neutrality debate, the principal straw man involves the potential (it's never happened so far) for Internet access providers, especially large ones serving customers nationally, to make side deals with the operators of some websites (Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Yahoo, eBay, perhaps) to manipulate Internet traffic at the last mile on their behalf.

Perhaps for a fee, in some alternate future, Microsoft would pay extra to have search results from Bing given priority, making it look "faster" than Google. That would encourage Google to strike a similar deal and, before you know it, only the largest content providers would appear to be worth visiting.

That would effectively end the model of the web that has worked so well, where anyone with a computer can be a publisher, and the best material has the potential to rise to the top. Where even entrepreneurs without a garage can launch a product or service on a shoestring and, if enough users like it, catapult themselves into being the next Google, eBay, Facebook or Twitter.

What does any of this have to do with Fox's activities over the weekend?

As Public Knowledge sees it, any interference with web content is a violation of the open Internet, even if that interference is being done by the content provider itself! Fox has programming content on both its own site and on the Hulu website, content it places there, like every other site operator, on a voluntary basis.

But, having once made that content available for viewing, according to Public Knowledge, it should be a matter of federal law that they keep it there, and not limit access to it in any way for any consumer anywhere at any time. It's only consumers who have rights here: "Consumers should not have their access to Web content threatened because a giant media company has a dispute over cable programming carriage." (emphasis added)

On this view, it's not content owners who have rights (under copyright and otherwise) to determine how and when their content is accessed. Rather, it is the consumer who has an unfettered right to access any content that happens to reside on any server with an Internet connection. Here's the directory to everything on my computer, dear readers. Have at it.

The "Government's Policy" Explained

Indeed, according to PK, this remarkable view of the law has long-since been embraced by the FCC. "We need to remember that the government's policy is that consumers should have access to lawful content online, and that policy should not be disrupted by a programming dispute."

Here's how Public Knowledge retcon's that version of "the government's policy."

Until this spring, the 2005 Federal Communications Commission (FCC) policy statement held that Internet users had the right to access lawful content of their choice. There was no exception in that policy for customers who happened to have their Internet provider caught up in a nasty retransmission battle with a broadcaster.

Said policy statement that was struck down [sic] on April 6 by the U.S. Appeals Court, D.C. Circuit, when Comcast challenged the enforcement of the policy against the company for blocking users of the BitTorrent [sic].

The policy statement was based on the assumption that if there were a bad actor in preventing the consumer from seeing online content, it would be an Internet Service Provider (ISP) blocking or otherwise inhibiting access to content. In this case, of course, it's the content provider that was doing the blocking. It's a moot point now, but it shouldn't matter who is keeping consumers away from the lawful content. (emphasis added)

Where to begin? For starters, the policy statement was not "struck down" in the Comcast case. The court held (courts do that, by the way, not statements of policy) that the FCC failed to identify any provision of the Communications Act that gave them the power to enforce the policy statement against Comcast.

That is all the court held. The court said nothing about the statement itself, and even left open the possibility that there were provisions that might work but which were not cited by the agency. (The FCC chose not to ask for a rehearing of the decision, or to appeal it to the U.S. Supreme Court.)

Moreover, there is embedded here an almost willful misuse of the phrase "lawful content." Lawful content means any web content other than files that users want to share with each other without license from copyright holders, including commercial software, movies, music, and documents. None of that activity (much of what BitTorrent is still used for, by the way–the source of the Comcast case in the first place) is "lawful." The FCC does not want to discourage—and may indeed want to require—ISPs from interfering, blocking, and otherwise policing the access of that unlawful content.

Here, however, PK reads "lawful content" to mean content that the user has a lawful right to access, which, apparently, is all content—any file on any device connected to the Internet.

But "lawful content" does not somehow confer proprietary rights to consumers to access whatever content they like, whenever and however they like. The owner of the content, the entity that made it available, can always decide, for any or no reason, to remove it or restrict it. Lawful content isn't a right for consumers—it just means something other than unlawful content.

Still, the more remarkable bit of linguistic judo is the last paragraph, in which the 2005 Open Internet policy statement becomes not a policy limiting the behavior of access providers but of absolutely everyone connected to the Internet.

The opposite is utterly clear from reading the policy statement, which addressed itself specifically to "providers of telecommunications for Internet access or Internet Protocol-enabled (IP-enabled) services."

But that language, according to Public Knowledge, is just an "assumption." The FCC actually meant not just ISPs but anyone who can possibly interference with what content a user can access, which is to say anyone with a website. When it comes to consumer access to content, it "shouldn't matter" that the content provider herself decides to limit access. The content, after all, is "lawful," and therefore, no one can "[keep] consumers away" from it.

The nonsensical nature of this mangling of completely clear language to the contrary becomes even clearer if you try for a moment to take it to the next logical step. On PK's view, all content that was ever part of the Internet is "lawful content," and, under the 2005 policy statement, no one is allowed to keep consumers away from it, including, as here, the actual owners of the content.

So does that mean that having put up this post (I presume the content is "lawful"), I can't at some future date take it down, or remove some part of it?

Well maybe their objection is just to selective limitation. Having agreed to the social contract that comes with creating a website, I've agreed to an open principal (enforceable by federal law) that requires my making it freely and permanently available to anyone, anywhere, who wants to view it. I can't block users with certain IP addresses, whether that blocking is based on knowledge that those addresses are spammers, or residents of a country with whom I am not legally permitted to do business, or, as here, are customers of a company with whom I am engaged in a dispute over content in another channel.

But of course selective limitation of content access is a feature of every website. You know, like the kind that comes with requiring a user to register and sign in (eBay), or accept cookies that allow the site to customize the user's experience (Yahoo!), or pay a subscription fee to access some or all of the information (The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times), or that requires a consumer see not just the "lawful content" they want but also, side-by-side, advertising or other information that helps pay for the creation and upkeep of the site (Google, everyone else).

Or that allows a user to view a file but not to copy and resell copies of it (streaming media). Or that limits access or use of a web service by geography (banking, gambling and other protected industries). Or that require users to grant certain rights to the site provider to use information provided by the user (Facebook, Twitter) in exchange for use of the services.

Paradise Lost by the D.C. Circuit's Comcast Decision

Or maybe their objection is just to when Fox does it?

Under PK's view of net neutrality, the Web is a consumer paradise, where content magically appears for purely altruistic reasons and stays forever to frolic and interact. Fox can't limit, even arbitrarily and capriciously, who can and cannot watch its programming on the Web. It must make it freely available to everyone and anyone, or face condemnation by self-appointed consumer advocates who will, as prosecutor, judge and jury, convict them of having committed "the grossest violations" possible of the FCC's open Internet policy.

That is, if only the law that PK believes represents longstanding "government policy" was still on the books. For the real tragedy of the Fox-Cablevision dispute is that the FCC is now powerless to enforce that policy, and indeed, is powerless to stop even the "grossest violations."

If only the D.C. Circuit hadn't ruled against the FCC in the Comcast case, then the agency would, on this view, be able to stop Fox and Hulu from restricting access to Fox programming from Cablevision internet customers. Or anyone else. Ever.

That of course was never the law, and never will be. More-or-less coincidentally, the FCC has limited jurisdiction over Fox as a broadcaster, but not to require it to make its programming available on the web, on-demand to everyone who wants to see it.

Fox aside, there is nothing in The Communications Act that could possibly be thought to extend the agency's power to policing the behavior of all web content providers, which these days includes pretty much every single Internet user.

Nor did the Open Internet policy statement have anything to say about content providers, period. If it had, it would have represented an ultra vires extension of the FCC's powers that would have shamed even the most pro-regulatory cheerleader. It would never have stood up to any legal challenge (First Amendment? Fifth Amendment? For starters…)

Not only does it matter but it certainly "should matter who is keeping consumers away from lawful content." When the "who" is the owner of the content itself, they have the right and almost certainly the need to restrict access to some or all consumers, now or in the future, without having to ask permission from the FCC.

And thank goodness. An FCC with the power to order content providers to make content available to anyone and everyone, all the time and with no restrictions, would surely lead to a web with very little content in the first place.

Who would put any content online otherwise? Government agencies? Not-for-profits? Non-U.S. users not subject to the FCC? (But since their content would be available to U.S. consumers, who on the PK view have all the rights here, perhaps the FCC's authority, pre-Comcast, extended to non-U.S. content providers, too.)

Not much of a web there.

No one Believes This—Including Public Knowledge

The wistful nostalgia for life before the Comcast decision is beyond misguided. No proposal before or since would have changed the fundamental principal that open Internet rules apply to Internet access providers only.

Under the detailed net neutrality rules proposed by the FCC in 2009, for example, the Policy Statement would be extended and formalized, but would still apply only to "providers of broadband Internet access service." Likewise the Google-Verizon proposed legislative framework. Likewise even the ill-advised proposal to reclassify broadband Internet access under Title II to give the FCC more authority—it's still more authority only over access providers, not just anyone with an iPhone.

(Though perhaps PK is hanging its hopes on some worrisome language in the Title II Notice of Inquiry that might extend that authority, see "The Seven Deadly Sins of Title II Reclassification.")

Public Knowledge has never actually proposed its own version of net neutrality legislation. So I guess it's possible that they've imagined all along that the rules would apply to content providers as well as ISPs.

Well, but the organization does have a "position" statement on net neutrality. And guess what? It doesn't line up with their new-found understanding of the 2005 FCC Policy statement either. Public Knowledge's own position on net neutrality addresses itself solely to limits and restrictions on "network operators." (E.g., "Public Knowledge supports a neutral Internet where network operators may offer different levels of access at higher rates as long as that tier is offered on a nondiscriminatory basis to every other provider.")

So apparently even Public Knowledge is among the sensible group in the net neutrality debate who reject the naïve and foolish idea that "it shouldn't matter who is keeping consumers away from the lawful content."

Did the rhetoric just away from them over there, or are those who support Public Knowledge's push for net neutrality really supporting something very different–different even than what the organization says it means by that phrase? Something that would extend federal regulatory authority to every publisher of content on the web, including you?

I'm not sure which answer is more disturbing.

Is the U.S. really behind in broadband?

I'd like to draw your attention to a recently released GAO report analyzing the challenge of implementing the 200+ recommendations included in the FCC's Broadband Plan and comparing the U.S. to broadband efforts in other countries. Turns out things are not as dire as the FCC and the Administration would have us believe. Some highlights:

Broadband internet is available to 95 percent of American households. This is comparable to other developed nations despite the U.S.'s larger geographic size and population.

"[T]he United States has more subscribers than any other OECD country–81 million, or more than twice as many as Japan, which has 31 million, the second highest number of subscribers."

The U.S. broadband adoption rate is 26.4 subscriber lines per 100 inhabitants, which is higher than the 23.3 average for developed countries.

So we have more subscribers than any other developed nation by more than double, and almost all households have access to broadband. I know it's not fashionable to say, but it looks like we're doing pretty damn well.

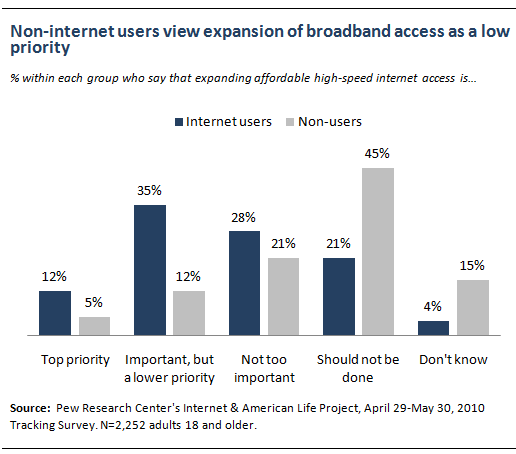

This might explain the results of a Pew Internet and American Life survey released last month that found that "A majority of Americans (53%) do not believe that increasing the availability of affordable high-speed internet connections should be a federal government priority." Interestingly, Americans who do not use the Internet are the least interested in seeing government spending on broadband–presumably for them." Fully 45% of non-users say the government should not attempt to make affordable broadband available to everyone, just 5% say access should be a top priority."

Kevin Kelly on technology evolving beyond us

On the podcast this week, Kevin Kelly, a founding editor of Wired magazine, a former editor and publisher of the Whole Earth Catalog, and one of the most compelling thinkers about technology today, talks about his new book, What Technology Wants. Make no mistake: the singularity is near. Kelly discusses the technium–a broad term that encompasses all of technology and culture–and its characteristics, including its autonomy and sense of bias, its interdependency, and how it evolves and self-replicates. He also talks about humans as the first domesticated animals; extropy and rising order; the inevitability of humans and complex technologies; the Amish as technology testers, selecters, and slow-adopters; the sentient technium; and technology as wilderness.

Related Links

"What Technology Wants", by Kelly at The Technium

"Building One Big Brain", by Robert Wright

Kevin Kelly on how technology evolves, TED Talk

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

October 18, 2010

WSJ Article on Facebook Feeds the Privacy Beast

The WSJ ran a front page, above-the-fold headline screaming that Facebook has had a privacy breach. But as Steve DelBianco discusses over at the NetChoice blog, today's WSJ "breach" is all smoke and no fire.

The WSJ is saying that some of Facebook's applications are accidentally sharing the public username on my Facebook page, in violation of the company's privacy policy. This story was nothing like a breach where my credit card numbers or sensitive personal information was leaked or hacked. A closer look at the issue indicates that there is far m

ore smoke than fire in the WSJ piece.

Moreover, the WSJ should step-back from using tabloid-style headings to attract eyeballs (and advertising revenue) to their research and writing. The breathless headline is clearly meant to feed the privacy beast that is increasingly in danger of doing far more harm than good.

While details are still forthcoming, it appears that the issue at hand involves external actions between application developers and advertising companies. Facebook has stepped-up and is holding third parties accountable to existing privacy requirements.

Are you ready for some News Corp?

Today's hot topic is that thousands of Cablevision customers in New York were faced with blacked out News Corp. channels, including Fox, when the two companies were not able to come to an agreement on fees. As a result, Cablevision did not carry the Giants-Lions game and may not carry the next game against the Cowboys. Glee on Tuesday is certainly threatened, and I feel for Cablevision because I wouldn't wish a spurned Glee fan's wrath on anyone.

The beautiful thing about this event is that the FCC has put out a Consumer Advisory enumerating all the various choices available to consumers. They can switch to a different pay service, and the FCC counts five: "AT&T, DIRECTV, DISH Network, RCN (limited areas of Brooklyn), and Verizon FIOS." They can also tune in via over-the-air (rabbit ears) broadcast.

This hasn't stopped Congress or "consumer advocates" from going apoplectic over American's god-given right to the Simpsons. And, since it seems News Corp. cut access to Fox shows on Hulu.com and Fox.com for Cablevision internet service subscribers, they fear this is terrible violation of net neutrality.

Let's put aside for a moment whether it's a net neutrality violation or not since it's difficult to tell what that means. (Notice that in this case is not big telecom carriers blocking access to content they don't like, it's a content provider blocking an ISP.) What exactly is the problem here?

Given that the FCC has helpfully pointed out all the options available to Consumers, there's little chance that a consumer who wants to get Fox content won't be able to do so. If Cablevision and News Corp. don't come to an agreement, and Cablevision doesn't carry Fox, consumers who value Fox will switch to a different service. The same goes for Internet service. The important issue here is not a universal human right to content or a net neutrality principle, but choice.

As long as there is market competition and consumer choice, we don't need the FCC or Ed Markey to ensure that the we'll get the Giants and the Cowboys in HD and Glee on Fox.com.

October 16, 2010

National Research Council Takes Biometrics Down a Notch

Late last month, the National Research Council released a book entitled "Biometric Recognition: Challenges and Opportunities" that exposes the many difficulties with biometric identification systems. Popular culture has portrayed biometrics as nearly infallible, but it's just not so, the report emphasizes. Especially at scale, biometrics will encounter a lot of challenges, from engineering problems to social and legal considerations.

"[N]o biometric characteristic, including DNA, is known to be capable of reliably correct individualization over the size of the world's population," the report says. (page 30) As with analog, in-person identification, biometrics produces a probabilistic identification (or exclusion), but not a certain one. Many biometrics change with time. Due to injury, illness, and other causes, a significant number of people do not have biometric characteristics like fingerprints and irises, requiring special accommodation.

At the scale often imagined for biometric systems, even a small number of false positives or false negatives (referred to in the report as false matches and false nonmatches) will produce considerable difficulties. "[F]alse alarms may consume large amounts of resources in situations where very few impostors exist in the system's target population." (page 45)

Consider a system that produces a false negative, excluding someone from access to a building, one time in a thousand. If there aren't impostors attempting to defeat the biometric system on a regular basis, the managers of the system will quickly come to assume that the system is always mistaken when it produces a "nonmatch" and they will habituate to overruling the biometric system, rendering it impotent.

Context is everything. Biometric systems have to be engineered for particular usages, keeping the interests of the users and operators in mind, then tested and reviewed thoroughly to see if they are serving the purpose for which they're intended. The report debunks the "magic wand" capability that has been imputed to biometrics: "[S]tating that a system is a biometric system or uses 'biometrics' does not provide much information about what the system is for or how difficult it is to successfully implement." (page 60)

"Biometric Recognition: Challenges and Opportunities" is a follow-on to the 2003 National Research Council report, "Who Goes There?: Authentication Through the Lens of Privacy." That book was one of few resources on identification processes and policy when I was researching my book, "Identity Crisis: How Identification is Overused and Misunderstood." (Mine is quite a bit more accessible than this new book, so if you're interested in the field, you might want to start there.)

There is nothing inherently wrong with biometrics. They will have their place, and they will make their way into use. But the dream of a security silver bullet in biometrics is not to be. Identity-based security—using the knowledge of who people are for protection—is valuable and useful in day-to-day life, but it does not scale. National or world ID systems would not secure, but they would carry large costs denominated in both dollars and privacy.

October 15, 2010

National Freedom of Speech Week is Oct. 18th-24th

Next week marks another "National Freedom of Speech Week" and each year I use this occasion as an opportunity to recall how lucky we are to live in a country that respects freedom of speech and freedom of the press. I wrote up a longer essay on this back in 2006 explaining why I am so passionate about freedom of speech and why I am so thankful to live in this country. For me, it comes down to is this: In a free society different people will always have different values and tolerance levels when it comes to speech and media content. It would be a grave mistake, therefore, for government to impose the will of some on all. To protect the First Amendment and our heritage of freedom of speech and expression from government encroachment, editorial discretion over content should always remain housed in private, not public, hands.

However, there will always be those who respond by arguing that speech regulation is important because "it's for the children." But raising children, and determining what they watch or listen to, is a quintessential parental responsibility. Personally, I think the most important thing I can do for my children is to preserve our nation's free speech heritage and fight for their rights to enjoy the full benefits of the First Amendment when they become adults. Until then, I will focus on raising my children as best I can. And if because of the existence of the First Amendment they see or hear things I find troubling, offensive or rude, then I will sit down with them and talk to them in the most open, understanding and loving fashion I can about the realities of the world around them. But I don't want anyone else doing that job for me. And in America, generally speaking, they can't. That's worth celebrating.

And then there's George. He alone makes freedom of speech worth celebrating:

Children's Programming, Product Placements & Trade-Offs

One of the old saws we hear from those who wish to impose more stringent regulations on advertising or product placement is that "it's for the children." That is, critics such at the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood and other organzations fear that, because children's brains are less developed or they have not yet learned to differentiate commercial appeals from other types of information flows, kids may be more susceptible to persuasive commercial messaging. I think there's some truth to that, but I also believe that (a) kids aren't quite the sheep we make them out to be, (b) the potential "harm" here is not as great as the critics make it out to be and (c) parental supervision should be the primary the solution to the problem.

But let's ask a different question entirely: Are we willing to forgo additional, and potentially more diverse, forms of children's programming simply because we want to keep commercial messaging or product placement away from kids? Consider the case study of The Hub, recently featured in The New York Times:

With imports of European cartoons, a smattering of Hasbro ads and a rerun of the movie "Garfield," Hasbro and Discovery Communications unveiled a new television brand for children on Sunday, called The Hub. Over time, the two companies hope to prove that there is room for a fourth player alongside Nickelodeon, the Disney Channel and the Cartoon Network, the three heavyweights of children's TV, said David M. Zaslav, the chief executive of Discovery Communications. […]

The Hub is a significant retooling of Discovery Kids, a channel available in about 60 million homes that had withered within the portfolio of Discovery Communications… . Discovery Kids came onto television after Nickelodeon and the Disney Channel, and it never found a competitive footing. It earned less than 10 cents per subscriber from cable and satellite companies, and most of its ads were of the low-rent direct-response variety. "We were really lying in wait," said Mr. Zaslav, who determined that he needed a business partner in the children's market, and last year found an eager one in Hasbro, which paid $300 million for a 50 percent stake in the channel.

As with most media programming decisions, a trade-off is at work here: To ensure diverse new shows or channels can be sustained, programmers must find revenue streams to sustain them. When direct subscription fees or other advertising methods prove unsustainable, the only remaining option is product sponsorship or some form of underwriting (unless we assume government funding for all children's programming is an option, which is neither likely nor desirable).

Thus, the cost-benefit calculus comes down to the choice between a new kids' channel that includes product promotion, or no programming at all. For some of us, this is an easy call: Diversity and choice should trump concerns about the supposed evils of "commercialism." Restricting advertising in the name of "protecting children," while well-intentioned, would limit cultural diversity and viewer choice and should, therefore, be rejected.

Of course, I feel passionately about that because I do not find the counter-argument convincing. Namely, I don't think the critics make a good case that a serious "harm" exists from exposure to commercial messages or product placement. Hell, I can't even count how many G.I. Joe-related product placement things I grew up consuming; I was obsessed with the stuff. But so what? Was I somehow irreparably harmed by it? And how about those endless Star Wars-related product placements? How were kids harmed by that? Because they begged Mom and Dad to buy more Star Wars toys? I could go on with countless examples, but you get the point.

Regardless, the point I am making above is a very different one: As a parent, would you rather have an additional option like The Hub, even if it includes some product placement / promotion, or would you rather not have an additional choice at all? Seems like a simple choice to me. And we should all be free to make it for ourselves and our families.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower