Beth Kephart's Blog, page 57

January 31, 2015

Peter Turchi on the value of sideways drafts, in A MUSE AND A MAZE

Last Friday evening, at an intimate salon, I had the privilege of hearing Peter Turchi, author of Maps of the Imagination, tease us toward his gorgeously crafted new book, A Muse and a Maze.

Last Friday evening, at an intimate salon, I had the privilege of hearing Peter Turchi, author of Maps of the Imagination, tease us toward his gorgeously crafted new book, A Muse and a Maze.(Read that title fast, and you'll get the point.)

Like the best of books, this one won't be easily classified. Puzzles and magic abound. Commentary on obsessions. Quotes on sentence rhythms. Forays into slow time. A slice from Bruce Springsteen (yes, my friends, that Bruce Springsteen). A few helpful definitions illuminating genres, puzzles, and mysteries. I'm not finished reading yet. It's not the sort of book one rushes. But an hour or so ago I came across Turchi's reflections on the real purpose of multiple drafts, and I knew that I could be accused of gross selfishness if I did not stop and share. I live for the next draft with my own work. I've gone horizontal-vertical-down-out-up, and if one were to apply aesthetic measures to my draft sequences one would shake one's head in pity. One Thing Stolen, my new novel, is the perfect example of a book that took more than a little swish and swirl (and more than a few tears, but I did not drown) before it found itself. But that is a story for another day.

With no further ado, then, Peter Turchi:

To learn to dwell in our work is to use drafts to explore, with the understanding that our movement toward the final draft of a story or poem or novel is likely to include not only lateral movement but backward movement, and circular movement, and movement we can't confidently describe. Because to insist to ourselves that each draft carry a story toward closure is, necessarily, to limit the possibilities. Every choice must then at least seem to be an improvement on what's currently on the page, part of a straight-line progression, rather than an alternative to what's on the page, movement within a larger plane. We need to allow ourselves to pursue hunches, to discover, in the words of Robert Sternberg, nonobvious pieces of information and, even more important, nonobvious relationships between new information and information already in our memory.

Published on January 31, 2015 04:12

January 30, 2015

The One Thing Stolen Teacher Guide

Jaime Wong of Chronicle Books masterminded one heck of a wonderful teacher guide to One Thing Stolen, the new novel which yesterday received its first official review, the Kirkus. The guide is now (as of this very minute) available online, here.

Jaime Wong of Chronicle Books masterminded one heck of a wonderful teacher guide to One Thing Stolen, the new novel which yesterday received its first official review, the Kirkus. The guide is now (as of this very minute) available online, here.With thanks to Jaime and to the designer who made this guide look so lovely — and to the programmer who made it available.

Published on January 30, 2015 07:26

January 29, 2015

Relief: The Kirkus Review of One Thing Stolen

“Rivetingly captures the destructive effects of mental and physical illness on a likable, sweet-natured teen.”—Kirkus Reviews

Something very bad is happening to 17-year-old Nadia.Ever since her family relocated to Florence for her father's sabbatical, she's been slipping out at night to steal random objects and then weave them into bizarre nest-shaped forms she hides from her family, and she's losing her ability to speak. The first section of the novel is related by Nadia in brief, near-breathless, panicky sentences that effectively capture her increasing disintegration. Switching smoothly between entrancing flashbacks of her promising past—"It was so easy, being me"—and her painful, confusing present, which includes visions of a "fluorescent" boy with a pink duffle, real or imagined, Nadia relates her story in fragments. Her parents, remarkably slow to realize Nadia isn't just having trouble adjusting, finally contact wise, nurturing Katherine, a doctor, for help. The narrative switches to the voice of Maggie, Nadia's beloved friend and soul mate, who joins the family in Italy to help Nadia and to find the duffle boy, whose existence—or not—has become critically important. It is he who narrates the final brief section. With Nadia's jumbled personality slipping away, the change of narrative voice is especially disquieting, offering few guarantees of a happy outcome. Disturbing, sometimes unsettling and ultimately offering a sliver of hope, this effort rivetingly captures the destructive effects of mental and physical illness on a likable, sweet-natured teen.

Published on January 29, 2015 18:25

January 28, 2015

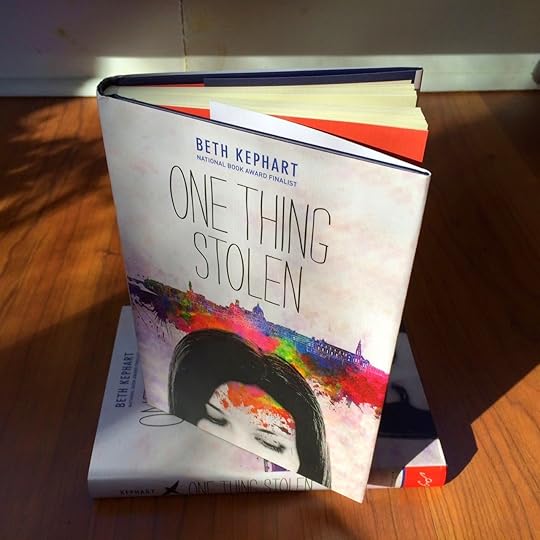

when you can still call it yours

when it still belongs mostly to you and the handful of souls who have made time to read.

when it still belongs mostly to you and the handful of souls who have made time to read.when it is as beautiful as this, all thanks to the design and editorial team.

before anything else can be said or done.

Published on January 28, 2015 10:52

January 27, 2015

trusting in the tomorrow we can't see

Recently, on Facebook, I made the announcement (pronouncement?) that I was going to worry less. The declaration prompted a fabulous chain of tongue-in-cheek responses, confessions, questions. The storybook stuff of the social media machine.

Recently, on Facebook, I made the announcement (pronouncement?) that I was going to worry less. The declaration prompted a fabulous chain of tongue-in-cheek responses, confessions, questions. The storybook stuff of the social media machine.But I was serious, more or less. I had awakened one day to the (obvious) realization that all the anxiety and worry that has accompanied my every waking hour has gotten me precisely nowhere. No better positioned as an author. No higher up on the chain of corporate commands. No richer and no younger.

What would happen if I stopped chasing the world and let it come to me? I wondered. What if I said that, for the next twelve months at least, I will proactively pursue—nothing. I will live my days fulfilling pre-existing responsibilities to family, friends, clients, editors, and students. I will finish the book-length projects that were promised, but not angst over new ones. I will do the work that arises of its own accord, write the columns I love writing, write the reviews that I love writing, teach the students I love teaching. Leave the in-progress novel where it is, simply in-progress, off to the side, rising like yeast. Expect nothing. Push back. Wait.

Leave the days to fate and to chance and to all the other forces that are at play out there.

A few weeks into this new frame of mind, and I can report this: Life is infinitely sweeter. In the hours I once spent searching for new work or scribbling novel lines, I'm reading—books I've chosen, books that assuage, alert, and teach me, books that I share here, books that are broadening my vocabulary. In the hours that once were noisy with demand I'm engaged in deeper conversations with new friends and old ones—about life, children, teaching, stories that matter. I've let that part of my mind that held onto disappointments or perceived betrayals, that wondered why not, that couldn't quite parse the hurts go white as today's snow.

I trust in the tomorrow I can't see.

Published on January 27, 2015 05:40

January 26, 2015

weather

As millions of us on the east coast wait out the blizzard headed our way, I send out thoughts of safe travel, warm homes, good books at hand.

As millions of us on the east coast wait out the blizzard headed our way, I send out thoughts of safe travel, warm homes, good books at hand.This is Alaska, this past June, where clouds and fog came in deep and thick, then vanished, leaving skies of radiant blue.

Published on January 26, 2015 03:54

January 25, 2015

Remembering South Street and celebrating Isaiah Zagar, in today's Philadelphia Inquirer

Last Friday I pushed away from the desk, went out into the air, and returned to South and Gaskill Streets. I rediscovered some of my own history. I talked with Julia Zagar about her husband's remarkable mosaics (Isaiah Zagar, Philadelphia's Magic Gardens). I remembered.

Last Friday I pushed away from the desk, went out into the air, and returned to South and Gaskill Streets. I rediscovered some of my own history. I talked with Julia Zagar about her husband's remarkable mosaics (Isaiah Zagar, Philadelphia's Magic Gardens). I remembered.The story is here, in today's Philadelphia Inquirer. Huge thanks to Kevin Ferris and to Amy Junod, page designer, who used six of my photographs for this piece. I'm sort of overwhelmed. I'm very grateful. Thank you.

Published on January 25, 2015 06:32

Everything I Never Told You/Celeste Ng and Citizen: An American Lyric/Claudia Rankine

There are books that fill you with the clamor of something new—the risk of them, the innovation.

There are books that fill you with the clamor of something new—the risk of them, the innovation.There are books that silence you—how honest and aching and true, how beautifully levered down into the soul.

This morning I am silenced by Everything I Never Told You, Celeste Ng's impeccable first novel about a daughter whose inexplicable death cracks open the vault of a family's secrets and regrets. A novel about children submitting to their parents' dreams for them, and the woeful consequences. Bill Wolfe had named this his favorite book of the year. Sarah Laurence had put it on her list. So many others, too. Believe anyone who tells you that you must read this book. Believe me. You must.

Ng is a master of the omniscient voice. A brilliant webber of divergent perspectives. A calm creator of sentences. A woman capable of writing with enormous clarity and tenderness about racism, silence, the terrible burdens of doing one's duty, the steep weight of holding that science book in your hand because your mother wants you to, the wretchedness of being the less-loved child. How do you take a heartbreaking story and still leave the reader with hope? You do it by writing through a powerful knowing not just of the past but of the future, too.

I am one of those people who writes in her books—outlining, defining, questioning. I did not write inside Ng's pages, preferring to keep them pristine. I turned back the ear of but one, knowing it would be the page that I shared, the thing that lies most at the heart of this novel. That word "different" and how we use it or abuse it in our lives.

Sometimes you almost forgot: that you didn't look like everyone else. In homeroom or at the drugstore or at the supermarket, you listened to morning announcements or dropped off a roll of film or picked out a carton of eggs and felt like just another someone in the crowd. Sometimes you didn't think about it at all. And then sometimes you noticed the girl across the aisle watching, the pharmacist watching, the checkout boy watching, and you saw yourself reflected in their stares: incongruous. Catching the eye like a hook. Every time you saw yourself from the outside, the way other people saw you, you remembered all over again.

I was reading Claudia Rankine's Citizen: An American Lyric the same time that I was reading Ng. I was thinking of how many times I have likely gotten it wrong in my own language—despite all these years now with my own Salvadoran husband, all these years fighting labels in life and on the page. Even those of us who should fully understand the nuances of prejudicial language can, horrifyingly, get it wrong, and will again. I mean to take nothing away from Ng's magnificent novel by including words from Rankine in this post, but they do, I believe, go together. They must—both these books—be read.

You are twelve attending Sts. Philip and James School on White Plains Road and the girl sitting in the seat behind asks you to lean to the right during exams so she can copy what you have written. Sister Evelyn is in the habit of taping the 100s and the failing grades to the coat closet doors. The girl is Catholic with waist-length brown hair. You can't remember her name: Mary? Catherine?

You never really speak except for the time she makes her request and later when she tells you you smell good and have features more like a white person. You assume she thinks she is thanking you for letting her cheat and feels better cheating from an almost white person.

Published on January 25, 2015 06:14

January 23, 2015

talking about failure memoirs, in this weekend's Chicago Tribune

In my memoir class at the University of Pennsylvania, we're focusing on failure/mistake memoirs, and what they teach us. To get my own self into a teaching place, I spent considerable time during Christmas and the first weeks of the new year, studying the books that I am teaching—and thinking.

In my memoir class at the University of Pennsylvania, we're focusing on failure/mistake memoirs, and what they teach us. To get my own self into a teaching place, I spent considerable time during Christmas and the first weeks of the new year, studying the books that I am teaching—and thinking.The Chicago Tribune kindly gave me room to put that thinking on its pages.

I'm thrilled to also be able to share that Daniel Menaker, the author of My Mistake and an esteemed editor in his own right, will be visiting Kelly Writers House for a publishers lunch and then my class on February 24th, at Penn.

The Tribune essay can be found here.

Published on January 23, 2015 09:14

January 22, 2015

When the poem is the elegy and the elegy is the memoir: Gabriel: A Poem/Edward Hirsch

This morning, before the gears on the work-a-day-world began to turn in earnest, I read "Gabriel: A Poem," Edward Hirsch's book-length elegy for his departed son.

This morning, before the gears on the work-a-day-world began to turn in earnest, I read "Gabriel: A Poem," Edward Hirsch's book-length elegy for his departed son.It is hallowed and hollowing, a work of pristine mourning. Memories seamed and broken. Threads that fall away until we see the soul of the boy himself— adopted, challenged by tics and relentless recklessness, the bright splash in a room. He is a child no one can keep safe from himself. A child who goes out during Storm Irene to a party he sees advertised on Craigslist. A child who does not return and cannot be found for four terrible days.

And then he must be buried.

It ransacks the soul, reading a book like this. We peel away as the lines peel away; no periods at the end of any line, no finished sentences. We look and we cannot stop looking until Gabriel, and his searching father, are a part of us.

It is a poem. It is also memoir. Like Jacqueline Woodson's Brown Girl Dreaming it suggests, again, another form for the hardest and most important stories lived. The most important things lost and lifted to the page.

Words:

In his countryWith thanks to Nathaniel Popkin, whose craft essay in Cleaver Magazine last week reminded me that I had meant to buy and read this.

There were scenes

Of spectacular carnage

Hurricanes welcomed him

He adored typhoons and tornadoes

Furies unleashed

Houses lifted up

And carried to the sea

Uncontained uncontainable

Unbolt the doors

Fling open the gates

Here he comes

Chaotic wind of the gods

He was trouble

But he was our trouble

Published on January 22, 2015 06:53