Beth Kephart's Blog, page 53

March 25, 2015

writerly responsibilities and rewards: words from the wise Dorothy Allison (yesterday, Kelly Writers House)

Dorothy Allison is one of three Kelly Writers House Fellows hosted this semester by Penn professor and poet Julia Bloch.

Dorothy Allison is one of three Kelly Writers House Fellows hosted this semester by Penn professor and poet Julia Bloch. Yesterday she sat among us, in conversation with us. There, beside Julia, she is.

Oh, I liked her. So very much. She's everything you've been told she will be. Iconoclastic. Irreverent. Touching. A firebrand of deep opinion and great craft cares who may believe in the act of revenge on the page, but only when the author holds him- or herself equally accountable for the unforgivable past. We writers, we survivors, may not be the heroes we think we are, Allison reminds us. We have responsibilities. Work that lasts is work that is rich with a felt sense of responsibility.

Any writer who believes that writing is a mere game—a toss-off and toss-up of the randomly odd, the relentlessly clever, the tried and true brand—must spend a bracing hour and change in the company of Allison. Sitting beside my friend Nathaniel Popkin and just one row ahead of August Tarrier (Jamie-Lee Josselyn waving a hand from the near distance, one of my students a few rows back), I filled my little notebook with Allison's words. I'm going to share a few of them here—transcribed as nearly as I could, but not always verbatim. Spread them, oh ye writers and readers who care.

In response to Julia's questions about craft (comments from across the conversation, gathered here): Craft sharpens the contradictions. It produces prose that takes the reader by the throat. Craft requires writers to read as writers, not as readers, and so we writing readers cannot merely wallow; we must assess. To make a reader care, the writer must keep paring the prose down, constructing the truth, acknowledging one's purpose. You are going for the long reach, not the quick tears. You want to haunt a reader six months on. The more talent you have, the more responsibility you have.

On writing with compassion: Recognize that you will never get it right. Recognize that those who survived, who got out of there alive, are in some ways the cowards, the ones who had to compromise. Hold yourself accountable for the choices you made. Recognize that you have a higher moral authority to tell the story right. This applies, by the way, to both writers of fiction and nonfiction.

On life's purpose: I don't want to be rich. I want a different world. I don't want the hatefulness of this world. I have a conviction about justice and social responsibility, a concept of citizenship at great variance with what I see in this world.

Paradise: is having an audience.

What the world is: We don't know what the world is until it is shown to us in story.

A story, much condensed (forgive me, Dorothy Allison, for this condensed version). In response to a question I asked about when Allison knew teaching was joyful, she first spoke of how she made sure to make teaching as hard for herself as it was for her students (amen to that, oh yes, amen to that), then told a story about one of the most talented students she ever had—a woman who didn't know where sentences began or ended, but knew vivid and had material. For nine weeks, Allison worked within a workshop and outside the workshop with this "baby" writer. That ninth week, they had a conversation about the writer's future. The student writer had a question: How much would she get paid for the stories she wrote? How much for a collection of stories? How much how much how much would she get paid—and how long would it take? Allison painted a picture of the future, spoke of the rewards that aren't numerical, finally confessed, when pushed, that her own most recent collection of words had received an advance of $12,500. "I earn that in tips a month," said this student writer. And that, pretty much, was it. The end of this genius writer's aspirations.

And so, Allison reminded us, one has to have more than a gift. One has to have desire. One has to cherish the audience, the chance to speak, the conversation—for that, in the end, is what matters most, that is the gifted writer's only sure provenance, that is where responsibility begins.

Let's get less caught up in the noise about books and more invested in making extremely fine ones.

Published on March 25, 2015 03:57

March 24, 2015

Helen Macdonald's Magnificent H Is for Hawk, in New York Journal of Books

I became obsessed with birds with the passing of my mother. The way they came to me. The way they called to me. The hollow of their bones. The other women, throughout time, who have buried their hearts in wings and feathers. This was the subject of my sixth memoir, Nest. Flight. Sky.: On Love and Loss, One Wing at a Time. This is the subject, again, of

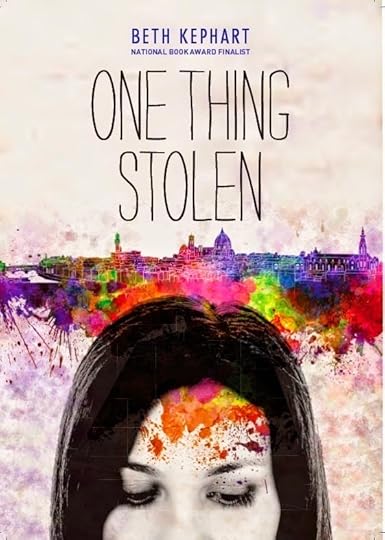

One Thing Stolen,

the obsession that lies at the heart of that book.

I became obsessed with birds with the passing of my mother. The way they came to me. The way they called to me. The hollow of their bones. The other women, throughout time, who have buried their hearts in wings and feathers. This was the subject of my sixth memoir, Nest. Flight. Sky.: On Love and Loss, One Wing at a Time. This is the subject, again, of

One Thing Stolen,

the obsession that lies at the heart of that book.And so when I began to read of Helen Macdonald's new memoir, H Is for Hawk, already a bestseller in England, I became desperate for the time to read that book myself. Over the past two days I have done just that, then sorted through my thoughts to write a review for the New York Journal of Books, where I'll now be penning my thoughts on literary adult fiction, memoir, and literary young adult novels.

The other day one of my students asked me to name my favorite memoir—an impossible question, of course. But now, whenever I'm asked that question, I'll be whispering Helen Macdonald's name. This is a book. Oh. This is a book.

The full review can be found here.

Published on March 24, 2015 04:01

March 23, 2015

realizing "our need of one another": Sarah Gelbard on our shared humanity

Not long ago, while I was enthusing about my students to a friend, I was stopped by a gently lifted hand and a question: "But don't you always love your students?"

Not long ago, while I was enthusing about my students to a friend, I was stopped by a gently lifted hand and a question: "But don't you always love your students?"But love, I wanted to say, is particular. Love is not an undifferentiated rush. Love happens because. Because of who these young people are, because of the community they've built, because they are working proof of the power of unshackled hearts and vulnerability and the kind of imagination that becomes another way of saying compassion. I love my students. I love these students.

Last week, while posting my HuffPo essay on My Spectaculars and their expectations regarding the memoirs they read, I promised that we would soon hear from Sarah Gelbard, my graduate student who slipped into our classroom as an auditor that first day and (we're so infinitely glad) stayed. A few Tuesdays ago, I asked Sarah, who works with the Friedreich Ataxia Program at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, to read to the class a piece she had written for Arts Connect International, where she was recently named content editor. I've been eager, ever since, to share this complete essay with you, especially in light of, well, everything. Including this.

Here is how Sarah's piece begins:

Disability is dealt arbitrarily; it is not a welcome present. Nobody goes to the gift shop, and says, “Ankylosing spondylitis— that sounds lovely!” Or, “I’ll take a brachial plexus injury for my brother on his birthday, with the red wrapping paper, please, and a free sampling of multiple sclerosis for me.” While I did not choose cerebral palsy, I do consider myself lucky to be a part of the disabled community. Through it, I have forged valuable connections with a great many, and we are allowed singular insight into the broad spectrum of human empathy. We encounter those who judge harshly, cruelly, fast to reject apparent otherness, and those who reach out seamlessly, kindly, fast to recognize apparent humanness.

Here is how it continues. Please read this. Please share it. It matters. So does Sarah.

Published on March 23, 2015 08:00

March 22, 2015

on compassion and (also) on negating our shame culture (Monica Lewinsky)

This morning I did that thing I love to do—plop on the couch, pull the fuzzy blanket to my chin, and read the New York Times online. It is one of my limited online reads. I value the words as much as the multimedia links.

Perhaps because I just finished writing and sharing a piece (in today's Chicago Tribune) on the empathetic imagination, perhaps because I teach memoir largely because I believe that teaching memoir is (or can be) akin to teaching compassion, perhaps because I have lived in shadows, too, been attacked, yearned for intervening empathy, the first two Times pieces I read today were compassion invested. The first, titled "The Brain's Empathy Gap" (Jeneen Interlandi), reports on studies designed to answer questions like: "How much of our empathy is innate and how much is instilled in us by our environment?" and "Why does understanding what someone else feels not always translate to being concerned with their welfare?" I recommend the read.

The second story, by Jessica Bennett, led me to this recent TED talk by Monica Lewinsky (yes, it was a busy week and I'm only catching up on this now; don't, as my student recently wrote, judge me), which I watched in its entirety. Brave, bold, bracing, Lewinsky reports from the depths of a personal hell and from the realities of a humiliation culture (as she puts it) that is shameful to us all.

Anyone who is out here in any public way—writing books, making songs, sharing ideas, blogging—knows that the risks are enormous. We see how a nano-second of inarticulate self-searching can become a Twitter storm. We see how a straying from the pact or pack opens the door to virtual mobster hatred. We see how a careless, insensitive Tweet can rearrange a life. And we see the opposite, too—how ideas or art or stories that do not conform to prevailing notions of cool, branded, or trending can go unseen, unheard, unheralded—which is, let's face it, a kind of humiliation, too.

Oh, it takes time to listen. Oh, it is so easy to judge. Oh, we can, from the protected privacy of our keyboard feel so empowered. Oh, anonymity is a sword.

But why build a world of cruelty when you can build a world of good? I laud Monica Lewinsky for asking that question. For standing up. For leaving the shadows.

Published on March 22, 2015 09:42

March 21, 2015

Walking West Philly with Lori Waselchuk and Writing ONE THING STOLEN, in this Sunday's Inquirer

Philadelphia Inquirer editor Kevin Ferris and I have been working together through many columns now, and I am always—always—grateful for his generosity. He has a huge heart. He allows me to write from mine. I'm neither a journalist nor an academic, and I'll never be famous. Kevin doesn't mind.

Philadelphia Inquirer editor Kevin Ferris and I have been working together through many columns now, and I am always—always—grateful for his generosity. He has a huge heart. He allows me to write from mine. I'm neither a journalist nor an academic, and I'll never be famous. Kevin doesn't mind.This month I wanted to celebrate West Philadelphia, where part of my new novel, One Thing Stolen (Chronicle Books), is rooted (much of the book also takes place in Philadelphia's sister city, Florence, Italy). I wanted to return to those images and places that inspired scenes in the book—and to Lori Waselchuk, a West Philadelphian who walked me through those streets two years ago to help me see them with insiderly eyes.

Lori is both a maker of art and a promoter of it. She is the force, for example, behind Ci-Lines, about which I wrote on this blog a few days ago.

To Kevin, who lets me love out loud, and to Lori, who gave me ideas that kept me writing forward, thank you. A note of thanks here, as well, to Hassen Saker, who offered kindness this week, and to Anna Badkhen, whose work inspired this blog a few days ago.

When the link to this story is live, I will post it here.

Published on March 21, 2015 08:24

March 20, 2015

how do we write with an empathetic imagination? thoughts in this weekend's Chicago Tribune

A few weeks ago, I built tall piles of my many essay collections (old and new) and began to ponder. Rediscovered favorite pieces by Annie Dillard, Patricia Hampl, Ander Monson, Rebecca Solnit, the World War II pilot memoirist Samuel Hynes, Elif Batuman, Megan Stielstra, Stephanie LaCava, Joanne Beard, others. Looked for insights into the empathetic imagination—how it has been managed over time, how essayists, historically, have gotten to the heart of hearts that aren't their own. I read, took notes, looked for patterns, began to write. It was a three-week process that produced just over 1,000 words.

A few weeks ago, I built tall piles of my many essay collections (old and new) and began to ponder. Rediscovered favorite pieces by Annie Dillard, Patricia Hampl, Ander Monson, Rebecca Solnit, the World War II pilot memoirist Samuel Hynes, Elif Batuman, Megan Stielstra, Stephanie LaCava, Joanne Beard, others. Looked for insights into the empathetic imagination—how it has been managed over time, how essayists, historically, have gotten to the heart of hearts that aren't their own. I read, took notes, looked for patterns, began to write. It was a three-week process that produced just over 1,000 words.I am blessed that the Chicago Tribune took interest in this piece. I am blessed, too, that I was able to share these thoughts at Bryn Mawr College this past Thursday, in the classroom of the very exquisite Professor Cynthia Reeves.

The essay will appear in this weekend's Printers Row. The online link is here.

Published on March 20, 2015 16:22

Consider joining us at Arcadia's Summer 2015 Creative Writing Workshops

Thanks to the generosity of Gretchen Haertsch (who wrote a very kind email a few months ago), I will be joining Arcadia as its Visiting Writer during this upcoming creative writing workshop. I'll be teaching the making of both fiction and nonfiction, read (from One Thing Stolen, I suspect), and answer questions.

Thanks to the generosity of Gretchen Haertsch (who wrote a very kind email a few months ago), I will be joining Arcadia as its Visiting Writer during this upcoming creative writing workshop. I'll be teaching the making of both fiction and nonfiction, read (from One Thing Stolen, I suspect), and answer questions.Please consider joining us. This summer program—one intensive weekend and four weeks online—will, I suspect, produce great yield.

Published on March 20, 2015 06:50

March 19, 2015

are we in ultimate control of our own artistic impulses?

In just a few hours, I'll be on the Bryn Mawr campus with my dear friend Cynthia Reeves and her students to talk about Handling the Truth, Flow, the empathetic imagination, the past and the present and—well—I have far too much planned for the hour and twenty minutes we have, but I guess that is who I have become. Persistent. Insistent. Still wrecked and unreasonable with the impossibility of it all.

In just a few hours, I'll be on the Bryn Mawr campus with my dear friend Cynthia Reeves and her students to talk about Handling the Truth, Flow, the empathetic imagination, the past and the present and—well—I have far too much planned for the hour and twenty minutes we have, but I guess that is who I have become. Persistent. Insistent. Still wrecked and unreasonable with the impossibility of it all. But this one One Thing Stolen thing before I go. The novel, due out shortly, is, as I have written here on Huffington Post, about a neurodegenerative disease—about the slow peeling away of my Nadia's language and historical self. Nadia, in One Thing Stolen, becomes trapped in a cycle of art making. She cannot stop herself.

A few weeks ago, Taylor Norman, a young and wondrously talented editor at Chronicle Books, took the time to send me this true story of a former lawyer whose traumatic brain injury resulted in the emergence of an unexpected artistic talent. This is art arising from injury and not disease. But it is, in so many ways, a story that yields insights into Nadia and into the question: Are we are in ultimate control over our artistic leanings, aesthetics, impulses? Can we definitively source the many ways that story, color, and shape erupt in us?

I would wager that we aren't, and that we can't.

From the story that Taylor sent that first appeared in the NY Daily News:

Doctors diagnosed Fagerberg with a traumatic brain injury. He suffered memory loss and had problems with processing language.

The accident ended his legal career. To cope, he turned to art therapy - and suddenly realized that he had a particular gift for painting.

"A little trigger went off and I became hooked. It became a compulsion," Fagerberg told KHOU, adding: "I see everything sort of in composition, so everywhere I look it's a painting."

The whole story, and a video, can be found here.

Published on March 19, 2015 04:06

March 16, 2015

loomed together in West Philly, with artists Lori Waselchuk, Aaron Asis, Anna Badkhen, and Hassen Saker

I traveled in Saturday's rain to St. Andrew's Chapel on Spruce Hill in West Philly to see the temporary art exhibition Ci-Lines, by Brooklyn-based artist Aaron Asis. I traveled to see my friend, the great visual storyteller and art provocateur, Lori Waselchuk, and to find community within a mostly shorn-of-purpose place.

I traveled in Saturday's rain to St. Andrew's Chapel on Spruce Hill in West Philly to see the temporary art exhibition Ci-Lines, by Brooklyn-based artist Aaron Asis. I traveled to see my friend, the great visual storyteller and art provocateur, Lori Waselchuk, and to find community within a mostly shorn-of-purpose place.I found even more than that.

I found:

An idea that had worked—the commanding uplift of blue stitchery (parachute cord) and the trace of nearly 1,000 art seekers.

The stories of historians, architects, seminarians. A story about a song.

Hassen Saker, a poet infused with sky.

Anna Badkhen, a writer of transporting nonfiction.

Lori and Aaron, the artists at work.

The chapel was cold. The afternoon light was a smear. The blue rope was illumination. "Like a loom," Anna said, and it was, and as the exhibit ended, as the stories and the community slipped back out into the rain, Anna and I stood talking about truth and honesty, about white space inside bold books, about what it might mean to be a citizen not of one country, but of the world. Not far from us, the knots of the blue rope were being undone. The weave was being let out of its loom. The blue was dissipating.

A camera paid attention to it all.

Published on March 16, 2015 04:07

March 12, 2015

What My Spectaculars expect from the memoirists they read, in today's HuffPo

Readers of Handling the Truth: On the Writing of Memoir know that—while I greatly vary the way I teach, the books I share, and the writers I invite to the classroom—there is one consistent essay I assign early-ish in the teaching season. A 750-word response designed to shake out ideas, ideals, and possibilities.

Readers of Handling the Truth: On the Writing of Memoir know that—while I greatly vary the way I teach, the books I share, and the writers I invite to the classroom—there is one consistent essay I assign early-ish in the teaching season. A 750-word response designed to shake out ideas, ideals, and possibilities.This year My Spectaculars produced such extraordinarily charming and elucidating responses to the assignment that I decided (with my students' permission) to knit together elements so that we might always have a record of Us. I've called the piece "How to Write a Memoir. Or (The Expectations Virtues)" and shared it on Huffington Post.

The piece, which begins like this, can be found in its entirety here.

I call them My Spectaculars. Together, we read, we write. We rive our hearts. We leave faux at the door. We expect big things from one another, from the memoirists we read, from the memoirists who may be writing now, from those books of truth in progress.(Read on, I exhort you. Find out.)

But what do we mean by that word, expectation?

It's a question I require my University of Pennsylvania Creative Nonfiction students to answer. A conversation we very deliberately have. What do you expect of the writers you read, and what do you expect of yourselves?

This year, again, I have been chastened, made breathless, by the rigor and transparency of my most glorious clan. By Anthony, for example, who declares up front, no segue: ......

There is a single student voice missing from this tapestry—my Sarah. You are going to be hearing from her next week or so, after a page or two of her brilliance is published and cross-linked here. Trust me, you will be changed by Sarah's words.

For now, I leave you my students. Read, and you'll call them Spectaculars, too.

Published on March 12, 2015 02:57