Beth Kephart's Blog, page 126

June 24, 2013

Transatlantic/Colum McCann: Reflections

Art. Yes. That's what Colum McCann produces, every single time. Read all his work. Read his short stories. You'll run out of ink underlining the extraordinary images, the soul-giant gestures, the coined terms, the Irishisms. You'll feel as if the clock of time just wedged itself apart, showed you its gears.

Transatlantic, the new novel, is no different. In fact, I feel this book transcends McCann's National Book Award winner, Let the Great World Spin. There is greater structural integrity, more generational reverb. Most reviewers seem to be talking about the elements of the book—the distinct chapters and historic characters that wend their way through the pages. A 1919 airplane flight. A glimpse of Frederick Douglass, the freeman, in 1845 Ireland. George Mitchell at the height of the Good Friday peace talks in 1998. I believe, however, that the genius lies in the seaming—in all that these chapters actually share, which is to say the generations of women who bind these historic crossings and events. Real people and imagined people populate this book in nearly equal measure. Both have been deeply imagined.

Look, for example, at these three paragraphs. The first two describe an historic character, one of the 1919 pilots. The second describes a McCann creation. History and possibility don't collide here, stiffly. They need one another:

At night Brown spends a lot of his time downstairs in the lobby of the hotel, sending messages to Kathleen. He is timid with the telegraph, aware that others may read his words. There's a formality to him. A tightness.

He is slow on the stairs for a man in his thirties, the walking stick striking hard against the wood floor. Three brandies rolling through him.

An odd disturbance of light falls across the bannister and he catches sight of Lottie Ehrlich in the ornate wooden mirror at the top of the stairs. The young girl is, for a moment, ghostly, her figure emerging into the mirror, then growing clearer, taller, redheaded. She wears a dressing gown and nightdress and slippers. They are both a little startled by the other.

Yesterday I wrote about the sound of McCann's sentences, the legacy he shares with Michael Ondaatje. Today I want to answer the NYTBR reviewer, Erica Wagner, who, in her very lovely review of the book asks why the final chapter of Transatlantic must be written in first person. I suggest (though I'll never actually know) that it all has to do with the book's final sentence. Which could not have been written any other way, and which left me weeping early this morning.

Published on June 24, 2013 10:34

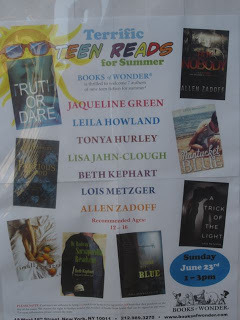

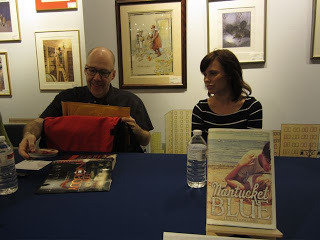

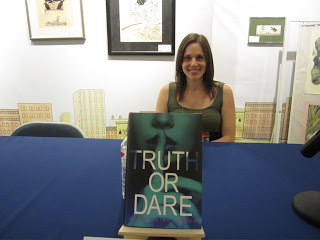

a lot of wonder at Books of Wonder

Books of Wonder did teen lit proud yesterday as it paneled widely varied authors, provoked a fine mix of strong opinions, and, as Allen Zadoff put it, reeled seven in-person book trailers for seven (or eight, depending on how you were counting) summer reads.

We had a glorious turn-out, and among those who joined us were my friends Patty Chang Anker (see my review of her forthcoming Some Nerve here), Jessica Francis Kane (whose novel (The Report) and story collection (This Close) I loved), and Melissa Sarno, whose novel has just gone out into the world under the auspices of her wonder-ful agent. We photographed Melissa, but that photo was a bit blurred.

(Also, I never got a photo of Tonya Hurley, but she was definitely there among us, and we were so grateful to have her in the house; Tonya and Peter may even go on a road show together, at least according to my listening ears.)

A huge round of thanks to the great Peter Glassman of Books of Wonder, who gave us all such a wonder-ful day.

Published on June 24, 2013 05:44

June 23, 2013

Michael Ondaatje, Colum McCann: the words between them

At Herbsaint Restaurant, on St. Charles, in New Orleans, I turned to look at the wall to my left, and there these musicians were. "That's Buddy Bolden," I said to my husband. And because Coming Through Slaughter is one of those rare books that I've convinced my husband to read, he knew what I was talking about. He knew that Buddy, the horn player, stood at the center of Michael Ondaatje's first novel. He knew that Ondaatje had captured the sound of the man's New Orleans crack up, during a parade down Canal. He knew that few writers thrill me the way Ondaatje does, that I've studied Ondaatje, that once Ondaatje wrote me a postcard in response to a long letter I'd written, and that once my agent, Amy Rennert, gave me a signed copy of Ondaatje's brilliant memoir, Running in the Family, a book I teach at Penn.

Ondaatje's postcard and that signed book two prized possessions.

Meet Buddy Bolden, in the early pages of Coming Through Slaughter:

He puts the towel of steam over a face. Leaving holes for the mouth and the nose. Bolden walks off and talks with someone. A minute of hot meditation for the customer. After school, the kids come and watch the men being shaved. Applaud and whistle when each cut is finished. Place bets on whose face might be under the soap.

Now meet Emily, a character in Colum McCann's expansive and predictably wonderful new novel, Transatlantic. McCann, another of my very favorite writers, a man I once met at the Philadelphia Free Library, my friend Aideen at my side. A man whose friendship with Ondaatje is legendary; acknowledged in the back of McCann's books, Ondaatje is also here, on McCann's website, in conversation.

In this scene from Transatlantic, it's just ahead of the stock market crash. Emily is an American writer born of an Irish mother who is taking a trip with her photographer daughter. She's one of several characters from several time periods who cross back and forth, across the ocean, between Europe and the United States, on the high wire of hope and time, in pursuit of freedom, a word with two syllables and many meanings.

The elaborate search for a word, like the turning of a chain handle on a well. Dropping the bucket down the mineshaft of the mind. Taking up empty bucket after empty bucket until, finally, at an unexpected moment, it caught hard and had a sudden weight and she raised the word, then delved down into the emptiness once more.

Michael Ondaatje and Colum McCann hear the word—and scribe the world—with the same meter. I can't read one without thinking of, or hearing, the other. Those spliced sentences. Those hushed sounds. Those surprising images. Ondaatje and McCann are come-closer writers. Come closer and pause. They are two men whose books are risks ribbed together by pierce and poem. Their sentences smoosh, then stand erect. They whisper, then they startle. They cut each other off and the joinery shocks us, as much as the flow of syllables.

What wouldn't you give to learn from either one? And then to forge your own sound, your own meter.

Published on June 23, 2013 05:14

June 22, 2013

celebrating the Wissahickon and its Friends in this weekend's Inquirer

It's a privilege, always, to celebrate the city I love. Huge thanks to Kevin Ferris, editor, and Amy Junod, page designer, for this gorgeously laid-out spread in this weekend's Philadelphia Inquirer.

Published on June 22, 2013 06:18

"Helping people should be nothing special..."

This morning I stole some time with the June 24 issue of The New Yorker. Readers of this blog know how much I feel I gain each time I open the pages of this magazine, how much sustenance it brings.

Several stories were of interest. Three I've clipped and filed. But for today, here, these are the lines I wish to share. I excerpt them from Larissa MacFarquhar's sympathetic profile of Ittetsu Nemoto, a Buddhist monk who has committed his life to helping the suicidal people of Japan. The piece, "Last Call," explores Japan's suicide culture and landscapes. It shares some of the letters Nemoto has received during his years of listening—and helping. And then it builds to a final, surprising page detailing the years during which Nemoto himself grew ill with five blocked arteries; his life was made even darker by the death of his father.

Through all of this, the suicidal people of Japan continued to call and e-mail Nemoto, continued to ask for his help. At one point, Nemoto grew too unwell to answer. When he could finally explain his silence to his correspondents, this man who had given everything to others was not met with sympathy.

MacFarquhar explains:

When he checked back to see how they'd responded to his announcement, he was shocked. They didn't care that he was sick: they were sick, too, they said; they were in pain, and he had to take care of them.

Lying in the hospital, he spent a week crying. He had spent seven years sacrificing himself, driving himself to the point of a breakdown, nearly to death, trying to help these people, and they didn't care about him at all. What was the point? He knew that if you were suicidal it was difficult to understand other people's problems, but still—he had been talking to some of these people for years, and now here he was dying, and nobody cared.

Ultimately, we learn, Nemoto chooses to help these people anyway. He recognizes the need to "stop thinking of this work as something morally obligatory and freighted with significance. Helping people should be nothing special, like eating, he thought—just something that he did in the course of his life."

Published on June 22, 2013 04:18

June 21, 2013

Some Nerve: Lessons Learned While Becoming Brave/Patty Chang Anker: Reflections

Photo Caption: National Book Awards, 1998, Reading at the New School. Left to right: Patty Chang Anker, my publicist; Amy Rennert, my agent; me with bangs; Louise Brockett, WW Norton publicist; Alane Salierno Mason, my editor.

My friends, gather round and listen well. I have a prediction to make:

{Patty Chang Anker is set to become America's next sweetheart.}

Yes, that's her, up there, on one of the most sacred nights of my publishing life—another century, another me. That's Patty as publicist, a UPenn graduate, before she was a mom. That's Patty before she, to use her word, changed. Let her explain:

Maybe it was forty and realizing that it wasn't just days but decades slipping by in the same worn paths that somehow grew narrower with each foray. Maybe it was the sense among friends that as we got older we were becoming more like ourselves, but not in a good way. I love you, but didn't we have the same conversation last week? Maybe it was the hypocrisy of stuffing my children into snowsuits and shin guards and helmets and sending them out into the fray while I cheered from a bench. Maybe it was a combination of all that and a last-gasp, premenopausal burst of hormones.

Whatever it was, after a lifetime of living nowhere near the edge, I had had enough. I started diving in.

Literally, Patty dove in. To the local pool. To de-cluttering her home. To public speaking. To biking. To surfing a frigid lake in winter. She went from supporting books to writing her own. And what a wonderful—and helpful—book it is. Endearing came to mind several times. Funny. Companionable. Sincere.

Some Nerve: Lessons Learned While Becoming Brave (Riverhead, October 2013) is precisely what its title promises, which is to say a journey away from fear and toward joy. It's Patty taking on the Greek Chorus that has both ransacked and italicized her thoughts. One part of her brain is telling her she can't swim. One part is leaving her on the sidelines. One part is encouraging her to talk out of both sides of her mouth as she cheers her two children toward things she has never done herself.

And then, hidden at first, more bold and ballsy in time, are all those other parts of her brain that say, Timidity is for the birds. Life is to be lived.

Patty introduces us to a world of helpful souls as she soldiers on—the expert de-clutterer, the teachers who believe, the friends who encourage her to swim, the toastmasters and psychologists and one writer/surfer dude. She made me smile time and again, not just because I know Patty—have known her for years now, have watched her evolve, have chuckled at her blog and her Facebook posts—but because every darned thing she writes is so quintessential in its own right that I know there'll be tens of thousands, no doubt more, smiling with her soon.

Patty has worked for a long time to become this more whole version of herself, and she has worked a long time to become this author. In a few short months, she's going to have so many friends/admirers/dudes in her life that she won't know what to do. I picture her, rock starish, being lifted up by hands and hearts set free, above a sea of lights.

Published on June 21, 2013 15:49

Come to Books of Wonder this Sunday so that you can see ...

all kinds of famous people. I'll be standing in their shadows, but I'll still be there. Also, there's this: Allen Zadoff, Tonya Hurley, and I will be dancing, all thanks to Jesse Klausmeier, who won't be there but is (if I am reading the Twitter feed correctly) going to be sending along several pink tutus for the Wonder people.

I've been practicing my flamenco.

More on all this marvelousness here.

Published on June 21, 2013 08:13

June 20, 2013

Reality Boy/A.S. King: Reflections

I didn't read A.S. King's Reality Boy on the day it arrived because I needed hunkering-down space. First, I've read all of King's books. Second, I'd heard King read the book's opening pages a few months before. I'd heard intense. I'd heard furiously fearless intense, King-quality fearless and King-quality intense, and there was no way I was going to read this book with interruption as a vague possibility.

I carried the book with me to New Orleans, but either the airplane was shaking or I was out walking NOLA or the TV was on in the recovering-from-the-heat-of-New-Orleans hotel room. Interruptions. No good. Have to read a King book straight through.

Just this morning I found my quiet hunkering-down hole and read straight through. And King, I gotta ask you something. I gotta know: How do you do this? How do you take a character straight out of reality TV—an angry kid, a messed-up kid, a kid with a messed-up family—and give him to us without any kind of buffers, without any kind of bowing to YA novelistic norms? How do you take a boy known as The Crapper for his childhood antics on Network Nanny and make him and his quest for normal, his quest to be released from the "viewers" who think they know who he, so incredibly real? How do you make his story so moving? His bedlam so believable? His awful world so finally transcended? How do you take so much anger and so much destruction and so much hopelessness and turn it on its head, King, without ever going to a soft place?

You are writing a story, and you are writing our TV-infected times. You are writing about not judging a person by the way the world has got him packaged. You are talking about mothers who are little bit cruel and sisters who definitely are, about dads who are trying to get out, about friends who are real, about arguments you can win, about a couple of adults who can see straight through to true, and about a girl in a wheelchair in the special ed class who has wisdom to share.

It's visceral, it's violent, it's fearless. And it says stuff like this:

This should be a reality TV show Except nobody would watch because it's no fun to watch normal people do normal things. Because happy stories aren't all that interesting. Because everyone wants to eat that shxt sandwich, or watch other people eat it, along with exotic bugs and rotten eggs and diesel fuel and everything else producers can think of to try to keep viewers' thumbs from the channel button on the remote control.

Last pages of the story had me crying, King.

And then I got to the acknowledgments and I cried some more. Thank you for that. Thank you for you and your books and our friendship.

Published on June 20, 2013 06:03

June 19, 2013

Country Girl: A Memoir/Edna O'Brien: Reflections

It's called Country Girl: A Memoir, and it was the word "memoir" that I kept stumbling over, that one word that kept causing me to stop, look up, ponder.

For certainly this life story by Edna O'Brien is fascinating on several levels and beautifully written in many instances, and certainly O'Brien is a formidable writer, an important one, a writer so revered that the life she lives—the life she writes about here—is peopled with the great writers and the celebrity actors and the rock stars, even Jackie Onassis and Hillary Clinton. The notorious and notoriously famous are her friends. Entire counties are her enemies. Everything is escalated in her world, and Country Girl gives us a vibrant view in.

Does it matter, then, that Country Girl is not truly a memoir? That Country Girl is, indeed, autobiography? At the heart of memoir lies a universal stance, a politics of readerly inclusion, a this happened to me, did it happen to you, and how, in the end, does this make us both human? At the heart of memoir themes percolate, and not just events. In autobiography, there is a divide—the audience in its seats, the storyteller on the stage, no mingling in the aisles, no presumed need for thematic integrity. Memoir gathers others in. Autobiography says, See, this. And this. Two very differently readerly experiences. Two different kinds of books.

Still, there was so much here—so much so beautifully rendered, so many episodes that provoke great sympathy, especially when the famous were off the page and it was O'Brien alone, O'Brien facing down her mother, O'Brien trying to recover her children from an angry ex-husband, O'Brien trying to write again, O'Brien musing on failure, and success.

And, always, O'Brien on love, of which she writes so knowingly:

Meanwhile, there was the vertigo of the affair, the many twists and turns, the reconsidered wisdoms, trade winds blowing hot and cold and hot again. It is impossible to capture the essence of love in writing, only its symptoms remain, the erotic absorption, the huge disparity between teh times together and the times apart, the sense of being excluded.

Published on June 19, 2013 13:40

Two Beth Kephart Pots (because some of you asked)

A few days ago I shared the pottery story I'd written for Good Housekeeping, and I loved hearing from so many of you who are potters too, or muck lovers.

I promised that I'd share a few of my novice pieces, and here two of them are—straight from the kiln. The little blue pot is my first true thrown pot—look at how tiny it is; I added coils to the top and a few decorative buttons. The second piece is another punctuation piece. It's me, working on the cusp.

Many thanks to my friends at the Wayne Art Center, who keep me moving forward, inch by inch.

Published on June 19, 2013 12:04