Beth Kephart's Blog, page 123

July 14, 2013

Join Debbie Levy and me in Alexandria, VA, as we share our new books and think about the fine line between truth and fiction

Over the next many months I'll be traveling around the country talking about books and how they get made. Often, I'll be doing this work in conjunction with writers I've always admired and cannot wait to meet. (Or announce here, just as soon as I can.)

This afternoon, I can formally announce the first such collaborative conversation, which I will be having with the esteemed author, Debbie Levy, a multi-genre, multi-award winning author of picture books, memoirs, and novels. We have shared interests, Debbie and I, and I can't wait to learn from her at Hooray for Books, in Alexandria, VA, on July 27, 2013. We'll start at 3:30 and end around five. We'll talk about truth and fiction and the lines in between, focusing on the four books I feature here—Handling the Truth (its first appearance in any store), The Year of Goodbyes (the winner of many awards), Small Damages (the first time I'll see its paperback self in any store), and Imperfect Spiral (just released). Debbie and I will both read—briefly—from each book, discuss its creation, and then share thoughts on workshopping truth and fiction. We each have an in-store exercise for those who'd like to try their hands at a bit of writing—and to hear our thoughts about their work.

I'm looking forward to meeting Debbie, to spending time at Hooray for Books, and to finally giving Deborah Yarborough a hug—for it is because of Deborah's sweet invitation that I will be there in the first place (and person).

Published on July 14, 2013 14:29

The Engagements/J. Courtney Sullivan: My Chicago Tribune Review

I'm always honored when the Chicago Tribune invites me to read one of the big books of the day—and to reflect on it for Chicago readers.

Today my review of J. Courtney Sullivan's The Engagements is up on the Tribune's Printers Row, one of the biggest printed book review supplements currently in circulation. It can be read in its entirety here.

Published on July 14, 2013 06:42

July 13, 2013

Scenes from the Independence Visitor Center Store, on a certain warm Saturday

Earlier today I was the guest of the truly beautiful and well-managed Independence Visitor Center Store on the Mall in Philadelphia. If you haven't been, you really should go. It'll make you proud of our city.

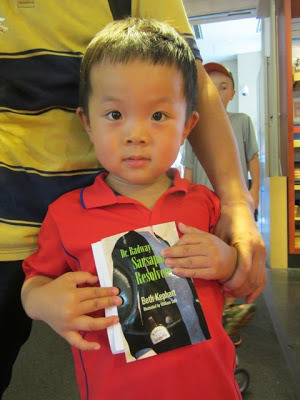

I was there to sign copies of my two Philadelphia novels, Dangerous Neighbors and Dr. Radway's Sarsparilla Resolvent. And as grateful as I was for the opportunity, I knew, going in, how hard this would be for this lifelong thwarter of sales scenarios. I couldn't sell Girl Scout cookies when it was required of me years ago. At other author events, I eschew talking about my own books in favor of promoting the books of others. And put me in the midst of a store with only my own books to sell, and all I can think of is how silly I must seem to all those passing by. An American curiosity with a twitch in her writing hand.

When I could climb out of my own head long enough, however, I was grateful for many things. For Sister Kim and her cousin Christine, who came and visited for a long sweet while. For the grandparents of twins, who embraced Dangerous Neighbors. For the junior in high school who hopes to be a writer, for the handsome couple who eventually overcame stormy skies and storm surges on the Chesapeake and made their way to the city, for the couple from Australia, for the couple from western PA.

And then there was this totally adorable little boy who could not get enough of the Dr. Radway cover. So convinced was he that he had to have this book that his mother and I began talking. She is a literature professor in China, as it turns out, at the end of a few months based in Boston, and it was fascinating to talk with her—and to hear her appreciation for this country. I was glad to hear that my fellow Americans had been kind to her and her family. I was glad to see the good of us through her eyes.

And that little boy—I'll never forget him.

I'm not good at sales. Indeed, I'm downright terrible at sales, suffering some inner shame as the clock ticks on. But today I was given the chance to see and hear the appreciation that others have for my city. It was enough for me. It was energizing.

Published on July 13, 2013 14:45

Who is in charge? Try this email assessment assignment and find out.

The other day I was amusing myself by reading The Secret Life of Pronouns by James Pennebaker, a book (to quote the book's web page) that is "based on a large-scale research project that links natural language use to real world social and psychological processes. Using computerized text analyses on hundreds and thousands of letters, poems, books, blogs, Tweets, conversations, and other texts, it is possible to begin to read people's hearts and minds in ways they can't do themselves."

I find the whole idea fascinating, though reading the book reminded me of how little I know about the labeling of verbs, say, not to mention how little thought I've given to "function words," which Pennebaker defines as pronouns, articles, prepositions, auxiliary verbs, and a few other language bits and pieces.

(I mean, there, that I've thought a whole lot about pronouns, obviously, being a memoirist and such. But I have not thought of pronouns as "function words.")

Among other things, the book looks at forgettable words, the words of sex and power, the words of liars, and the words of love. He gives his readers exercises and I'll share one here. I haven't done it myself yet—afraid of what I will find out. But I share it with you, and hope that you'll let me know what you find out. (Look at all the non-I words in that last sentence. I think I've just rendered myself an overly self-impressed human being.)

Look at the last ten e-mails that you sent to someone and compare them with the last ten they sent you. Calculate the percentage of I-words each of you used. If you have a great deal of time, you can do the same with the you- and we-words that you both used as well. Statistically, I-words are the most trustworthy. Here's the rule: The person who uses fewer I-words is the person who is higher in the social hierarchy. If the two of you are about the same in I-word usage, you probably have an equal relationship.

Published on July 13, 2013 06:49

July 12, 2013

The Boy on the Bridge/Natalie Standiford: Reflections

It's 1982, and Laura is spending a semester in Russia, learning the language of a country she fell in love with years ago. Leningrad is freezing cold and gray. The food is fish head soup and gristle. Gypsies have begun harassing Laura on the bridge that spans the Neva River and she is alone, and afraid, when a boy—a Russian boy—makes them stop. He has "smooth fair skin, rosy cheeks, mischievous brown eyes" and he goes by the name of Aloysha.

Laura will, over the course of Natalie Standiford's The Boy on the Bridge, fall in love with Aloysha—breaking all the rules of her semester abroad, cutting classes, and risking expulsion for herself as well as a darker, more mysterious brand of danger for Aloysha. She will be cautioned—by friends, teachers, other Russians—against a Russian system that makes marriage to an American the best possible ticket out of a life of thwarted opportunities. She is just nineteen. She believes in love. She believes Aloysha is in love with her. But is it love, or is it a desire to flee the country that has wounded and encased him?

Standiford, who spent a Russian semester abroad years ago, writes with great authority about the Russian landscape, the tourist spots and the off-the-beaten-path interiors of Russian apartments and bookstores. She writes knowingly, too, about the near impossibility of being sure. Is the rapid fire of this passion really love? Does Aloysha's desire to leave his country shape his claim of passion—or the stories he tells? Is Aloysha even capable of being honest with himself?

It's complicated, and Standiford presents the complications compellingly well—tugging the reader through to the final pages of the book as we wonder—begin to need to know—precisely what will happen here to an American college girl in love.

Look for The Boy on the Bridge in August.

Published on July 12, 2013 06:48

July 11, 2013

Small Damages: it's paperback pub day!

The very great Jessica Shoffel sent me this copy of Small Damages, delivered on the day of the book's paperback release by the Penguin imprint, Speak.

It's a beautiful package, this book. Ever since Tamra Tuller acquired this story for Philomel, it has been given extraordinarily good care—through editing and copy editing, through design and publicity, through its transformation as a paperback.

I placed my implicit trust in Tamra, Michael Green, Jessica Shoffel, and the sales team, and I was never given a reason to doubt. When Eileen Kreit and her team assumed responsibility for the paperback, I was equally at ease.

So much can go wrong in the publication of a book. Nothing went wrong with this one. I am so proud and happy to have my first paperback (with the stepback!) copy of Small Damages in hand. And I will be grateful, always.

Published on July 11, 2013 11:13

Gearing up for the Handling the Truth workshops (and see you at Independence Mall this Saturday?)

The other day, when my very bright orange Handling the Truth arrived, I took a very deep breath. It is time, I thought. Time to think about the way I will talk about this book and take it out into the world.

I'm still happy for the decision I'd made months ago to conduct workshops on behalf of this book, as opposed to offering traditional readings. Some of those workshops are noted on the left column of this blog—events in Alexandria, VA, Philadelphia, New York, and elsewhere. Three will be conducted in northern California. One of those (noted above) will take place at one of my very favorite independent bookstores, Book Passages.

I hope to see you in my travels. And I hope, perhaps, to see you this Saturday, when I'll be signing copies of Dangerous Neighbors and Dr. Radway's Sarsaparilla Resolvent on Independence Mall. It's gorgeous down there; it's the heart of Philadelphia history.

July 13

1:00-4:00 pm

Independence Visitor Center Store

1 North Independence Mall West

6th and Market Streets

Philadelphia, PA

Published on July 11, 2013 05:02

July 10, 2013

The Art of Intimacy: The Space Between/Stacey D'Erasmo

Always a cause for celebration when a new volume in the The Art of series is released by Graywolf Press. Edited by Charles Baxter, the "series is a line of books reinvigorating the practice of craft and criticism." The Art of Subtext (by Baxter himself), The Art of Time in Memoir (by Sven Birkerts—a book I love and teach and feature in Handling the Truth ), The Art of Recklessness (Dean Young), The Art of Attention (Donald Revell), The Art of Description (Mark Doty)—these are ingenious encapsulations of a working writer's best thinking on the making of stories, sentences, and poems.

Yesterday, Stacey D'Erasmo's contribution to the series—The Art of Intimacy: The Space Between—was released; I had it on my iPad by dawn. D'Erasmo is a writer and reader worth heeding—an honored novelist, a professor at Columbia, a critic whose reviews are often better than the studied books themselves. Here, in this book, she does exactly what her title promises—explores "the nature of intimacy" and "the space between us" through chapters with titles like "Trying to See," "Meeting in the If," "Meeting in the World," "Meeting in the Dark," "Why Meet?," and "Distance." Old favorites like The Secret Sharer, The Rainbow, So Long, See You Tomorrow, Beloved, and To the Lighthouse are reinvigorated here, reviewed with an eye toward blurred, encapsulated, empathetic, and haunted spaces. Lesser known (to me, anyway) texts such as Dennis Cooper's My Mark, Nella Larsen's Passing, and Yoko Tawada's "The Bath," are likewise studied, quoted at length, turned over like conical shells.

I don't know about you, but I find this sort of thing thrilling—viewing texts through the eyes of a skilled, practicing writer. D'Erasmo has ideas; she makes assertions. "I have noticed that the intimacy we feel as readers is often generated far less by characters turning to one another and saying intimate things or doing intimate things than it is by a kind of textual atmosphere, or maybe one should say a biosphere, a gallery, a zone that both emanates from characters and acts upon them very deeply and personally," she asserts early on.

Later, she addresses her readers as probable writers:

The harm, it seems to me as a struggling writer among other struggling writers, is that piety of any kind is never especially good for art. Characters can, and should, believe all kinds of things, passionately and with brilliant wrongheadedness, but the book is, generally speaking, up to something else, something broader, something less sure of itself. Questions the writer might ask herself as she struggles to bring a sense of intimacy onto the page are, What assumptions am I making about what intimacy is? What received ideas about intimacy am I perhaps unwittingly reproducing?

It's all fascinating to me—elevating my vocabulary as a reader, expanding my girth as a writer. And so, on this morning of vapid fog and gathering heat, I send it out to you, dear readers, as a book to buy and keep.

Published on July 10, 2013 03:53

July 9, 2013

Jill Lepore: The Prodigal Daughter

Each year, for the Lore Kephart '86 Distinguished Historians Lecture Series, a group of faithful Villanova University scholars (including my good friend Paul Steege) work with my father to choose a speaker who will engage the Villanova students, faculty, and greater community. In 2011, that speaker was Jill Lepore, whose work I have always admired and whose presentation on Jane Franklin, Benjamin Franklin's sister, was exquisite. Jill was working on a book, she'd told us. What a great a book we knew it would be.

In this week's New Yorker, Jill Lepore contributes an essay titled "The Prodigal Daughter" that interleaves her research on Jane Franklin with her own growing up with a mother who was primed for beauty and who insisted that Jill go out and embrace the world. It is the most personal essay I've ever read by Lepore—and, by far, the most wrenching. It bears reading by any writer seeking proof of how the personal can elevate the historical, and how history bears on the present day. The final paragraph of Lepore's essay made me weep, literally. But let me share here the place where it all begins:

In the trunk of her car, my mother used to keep a collapsible easel, a clutch of brushes, a little wooden case stocked with tubes of paint, and, tucked into the spare-tire well, one of my father's old, tobacco-stained shirts, for a smock. She'd be out running errands, see something wonderful, pull over, and pop the trunk. I never knew anyone better prepared to meet with beauty.

And later—a passage I remember well from Lepore's 2011 talk:

He ran away in 1723, when he was seventeen and she was eleven. The day he turned twenty-one, he wrote her a letter—she was fourteen—beginning a correspondence that would last until his death. (He wrote more letters to her than he wrote to anyone else.) He became a printer, a philosopher, and a statesman. She became a wife, a mother, and a widow. He signed the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Paris, and the Constitution. She strained to form the letters of her name.

Lepore's new volume, Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin, is set for publication in October. My mother would have loved Jill Lepore. If you don't already love her, you will after reading "The Prodigal Daughter."

Published on July 09, 2013 05:49

July 8, 2013

Celebrating Craig Park and his first published essay, in the Pennsylvania Gazette

We'd already settled into our paces in English 135.302 this past spring when Craig Park joined our ranks—a trim guy in a slim jacket; dark eyes; a closely-shaved head. I wanted to know what he hoped to achieve in our class and asked. He looked at me, let a beat of time go by. "That's an awfully personal question, isn't it?" he asked.

Hmmm, I thought. This should be interesting.

And it was interesting—completely interesting—as Craig soon proved himself to be a gifted writer, an astute critic, a young man with wild stories to tell. He's terribly bright, this Craig Park—bracingly talented with language, tempo, detail. But he was also quick to admit how tricky memoir is, how hard it is to help a story (even a monstrously good one) transcend itself.

Some students come to us with talent and smarts to spare, and Craig was absolutely one of those. Others come with a willingness to say, I don't know this particular thing yet, but I'm willing to do what it takes to deepen my understanding—and range. Craig also proved himself to be one of those. That combination—in any person—is a powerful one, and as the semester wore on, I gained great respect for the intelligence and heart that Craig brought to his work. I pushed him, and he let me. That, too, counts for a lot.

Still, Craig's sentences—the long, the short, the lacerating, the gentle, the sometimes philosophical. I had nothing to do with them. Craig had that going on from the start.

I'm proud and pleased today to share Craig Park's first published essay, in the pages of the esteemed Pennsylvania Gazette. Great thanks to Trey Popp, who comes to my classroom each semester and makes room for these young writers.

Craig's essay begins like this, below, and carries forward here.

I stood by the highway on-ramp and waited for the next potential ride. I

had changed out my selection of signs, and I was testing the

effectiveness of a minimalist “South?” on a floppy cardboard rectangle. I

hoped the one-word request achieved the necessary generality. People

don’t tend to stop for hitchhikers demanding specific destinations, but

my open-ended pleas struck me as inevitably effective given my proximity

to a north-south highway. “Inevitably effective” might have been a bit

too much confidence, though; after the fifth or sixth refusal, I started

to worry that I wouldn’t make it out of Jersey by nightfall.

To read the published Gazette essays of other students with whom I've had the privilege of sharing the classroom, please visit my Handling the Truth: On the Writing of Memoir page.

Published on July 08, 2013 09:35