Arnon Z. Shorr's Blog

August 10, 2025

When Meritocracy Meets Diversity: Lessons from a Jewish Pirate Film’s Removal from Amazon

July 21, 2025

A Screenwriter’s Contest Strategy to Keep You Sane – Post‑Coverfly Update

April 3, 2024

Top List of Films that Every Filmmaker Should See

In the latest episode (#637) of the excellent Scriptnotes podcast, hosts John August and Craig Mazin spend some time discussing lists of the greatest movies (like AFI's "100 Years... 100 movies" list of the greatest American films). A recurring question that they ask each other when discussing titles that appear on these lists is whether or not it is necessary to have seen a particular film. John and Craig aren't talking to film fans in their podcast, but to filmmakers and screenwriters - professionals or aspiring professionals in the entertainment industry. The question of necessity, then, is one of professionalism.

They argue - correctly, I think - that in most Hollywood settings, the most useful references these days are references from within the last several decades. For the most part, the films they discuss are from 1980 or later. From a business standpoint, this is certainly true - whatever made for a box office success in 1952 simply isn't relevant today.

But creatively, I've found that familiarity with certain older films has been extremely helpful to me as a filmmaker and as a screenwriter (and even, on occasions, as a writer of comic books).

So I decided to begin a Best Films List of my own. This is the beginning of an incomplete list and an eternal work-in-progress, though I will probably close the list once it hits 100 titles. These are films that I feel can inform and inspire creative choices for filmmakers and screenwriters today, regardless of when the films were produced or released. A list of top films for filmmakers.

Most importantly, along with each title, I will share a few brief thoughts about why I think the title is creatively important for filmmakers and screenwriters to be familiar with. This, I think, is a big failing of many top-10 or top-100 film lists. AFI's list is wonderful, but there's no hint as to what makes each film great. And the thing that makes one film great might be unrelated to what makes another film great. It's a fun way for movie fans to discover new movies, but it's not as helpful an educational tool for those of us who are working to improve our filmmaking.

Note: If a film is available on Amazon, I'll include a link. This is an affiliate link. Because... why not?

Last updated: 4-3-2024

This classic from Sidney Lumet basically takes place entirely in the jury room of a stuffy courthouse on a hot day. It's a fantastic study in how to maintain tension and interest in a contained environment - particularly if it's viewed in conjunction with Lumet's fantastic book, "Making Movies", where the luminary director discusses his visual strategy of changing camera angles and focal lengths as the story progresses to maintain visual interest. For filmmakers considering making a contained thriller (or a contained narrative of any kind), a close study of this film - and the accompanying essay in Lumet's book - is required.

This film comes up all the time, nearly a century after its release (and much longer since the publication of the book that inspired it). Frankenstein's monster is both horrifying and - through James Whales' masterful storytelling - painfully sympathetic. Any time I've ever discussed a monster story where the monster isn't just a monster, "Frankenstein" has come up as the reference point. Arguably, King Kong (elsewhere on this list) could also serve the same function, as that film's monster is also somewhat sympathetic by the end. But for some reason, it's always "Frankenstein" that emerges as the useful example. Some of the film's imagery has become iconic, too, and is worth getting to know.

What is there to learn from this old classic? Everything this film did right has been repeated by Hollywood blockbusters for over 90 years. But I've found this film a useful reference when exploring a particular quirk of narrative structure: The best movies don't end when the hero achieves the hero's superficial goal. In King Kong, the protagonist filmmaker's goal is to come home with something to brag about. He succeeds... at the end of the second act, when he decides to drag the unconscious Kong back home to New York. The film could have ended there - and many lesser stories do end in this way, with the achievement of a protagonist's stated goal - but this film doesn't. The protagonist's very success is is the "second act slingshot" that launches the story into the legendary Manhattan climax. You know what other movie does this? Star Wars! Luke achieves his stated goal of becoming an intergalactic hero when he rescues the Princess from the Death Star. But in rescuing the Princess, Luke inadvertently leads the Empire to a critical secret rebel base... and launches the film's climactic third act. So, yes, you can learn this lesson from "Star Wars", too, but I've found the "King Kong" example particularly powerful, perhaps because that film's third act is so different. It's almost a separate movie, but it still feels organically and essentially connected to the rest of the story.

This silent classic from the peak of German expressionist filmmaking has had tremendous impact on film design, particularly for science-fiction films, but also for movie musicals and other forms of "spectacle". Don't watch it for the story, which isn't bad, but isn't particularly special, either. Instead, watch it for the design - the framing of the shots, the use of visual effects, the way large crowds of extras are directed and choreographed. You might be surprised by how much of it feels familiar and recognizable from recent film and TV.

There's a lot we can still learn from Orson Welles, but I think there's more to learn from this later film than from his groundbreaking classic, "Citizen Kane." (If you do watch Kane, try to find a DVD with the late Roger Ebert's stupendous audio commentary). The two things I keep coming back to in "Touch of Evil" (well, three, if you count the incredible score) are the use of light and the camera movement in the film's many long takes. Coming at the very end of the original film noir era, "Touch of Evil" uses every trick in the book to create evocative, moody, and in some cases quite ominous lighting that does wonders to contribute to the story. And the long takes... The legendary opening shot is a spectacle to behold, but watch the film carefully, and you'll see there are several moments in the film where the camera simply doesn't cut at all. Long, drawn-out takes with complex choreography between subjects and camera. It's done so well that you might not even notice it at first. Even today, few filmmakers know to achieve this level of mastery of a long take. Spielberg and Cuaron have done it well - Spielberg in "War of the Worlds," Cuaron in "Children of Men." (And I'm not talking about long-take 'gimmick' films like Cuaron's "Gravity" or Sam Mendes' "1917" - both excellent, but neither quite achieving this unique effect of incorporating a very long take into an otherwise traditionally filmed and edited narrative).

As mentioned above, this list is just the beginning - a work in progress on my end that will never fully encompass every useful piece of cinema out there. What movies do you think are essential viewing? Remember, the question here isn't what movies are "great" - or what movies are "important" from an historical standpoint. The question is: for filmmakers and screenwriters, what are the films that we must study to elevate our craft, and to be conversant about our craft within our industry? Feel free to suggest more titles in the comments below!

February 20, 2024

Translating a Comic Book from English to Hebrew

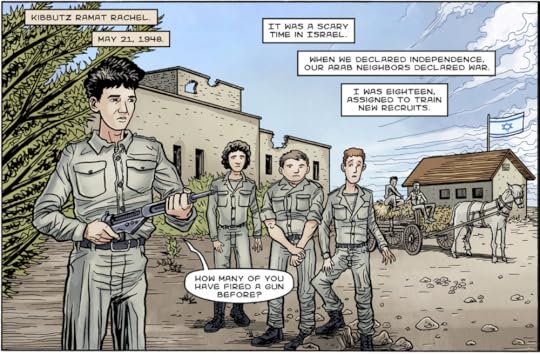

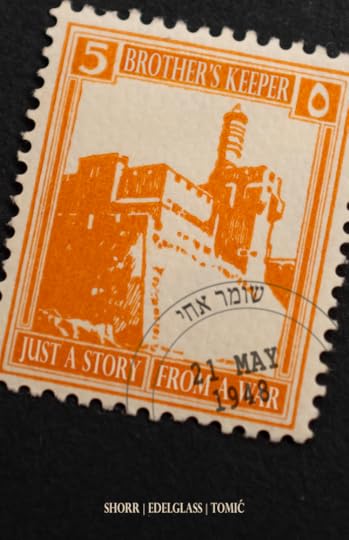

Over the summer of 2023, Joshua M. Edelglass and I agreed to collaborate on an independent single-issue comic book called "Brother's Keeper". The book tells my grandfather's story from Israel's 1948 War of Independence.

That story, which begins with a fierce battle at a kibbutz on the outskirts of Jerusalem, took on a whole new meaning in October, when history echoed and kibbutzim in Israel were attacked once again. I've already written about the strange experience of having my story's meaning suddenly shift in this way.

Josh and I originally planned for a slow and casual release of the book, but with the outbreak of war, we determined that the story had to be made available faster, and to a broader audience. As part of that new strategy, I really wanted to find a way to translate the book to Hebrew, and to make it available in Israel.

Step One: The TranslationThe first step to translating any comic book is - of course - the translation itself. Although I'm a fluent Hebrew speaker, growing up in the US has left me with a vocabulary that's full of holes. The book features military and medical terminology that I knew I wouldn't be familiar with, and I imagined that there are turns of phrase in the English that would require some finessing in order to feel similarly natural in the translation.

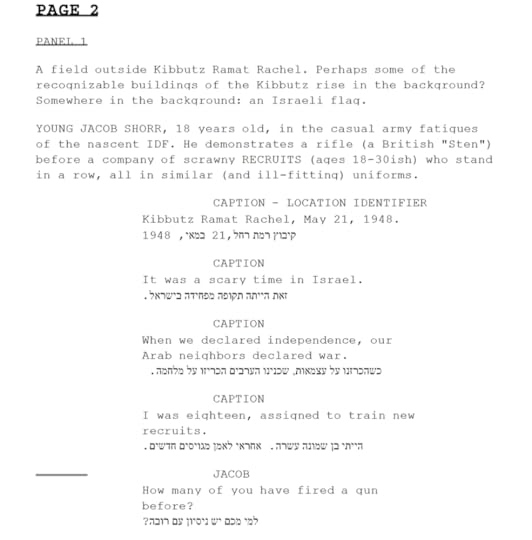

So I recruited the help of my parents, both of whom have translation experience. My mother, in particular, has been teaching University-level Hebrew for decades, and is extremely well-versed in the language. They worked off of my book script, and went caption-by-caption and dialogue-by-dialogue to translate the entire work. Of course, there was no need to translate the panel descriptions - those are merely instructions for the illustrator, and don't appear in the published book.

This would normally be the end of the primary translation process. But since we were translating to a language that I can speak, I was able to review the work and suggest changes.

In fact, the three of us got together one afternoon and combed through the translation line-by-line. The translation was accurate as far as the individual meanings of the words went, but there were questions of tone and style that had to be addressed. This is where translation shifts from being a craft to being an art. In one panel, a caption reads, "Some of us ran out of luck" in proximity to an illustration of a dead soldier on the battlefield. Idiomatically, the literal translation simply didn't pack the same emotional punch in Hebrew. So, together, we explored different Hebrew idioms, and settled on something like "for some of us, this was the end of the story."

With the translation complete, it was time to prepare the book for Hebrew lettering.

Step Two: Reversing the PagesComics stories are told in individual illustrations, called "panels", that are usually meant to be read in a particular order. In English language comics, you begin with the top-left panel of the page, then work your way gradually across to the right, then down, largely following the same visual flow that you would follow if you were reading sentences and paragraphs in a book.

Within each panel, speech bubbles are arranged strategically so that you read them in the same left-to-right manner. In fact, when illustrators illustrate comics, they try to place the first character who speaks on the left side of a panel so that the character's speech bubble can easily be placed where it will be read first.

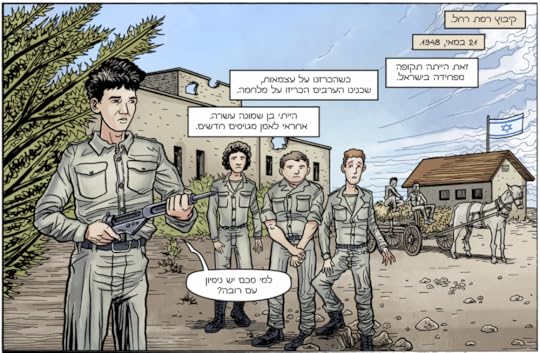

When translating a comic book to a right-to-left language such as Hebrew, it becomes necessary to flip all of the pages so that the action and dialogue also flows right-to-left. This is important page-wide, and also within individual panels.

For much of "Brother's Keeper", flipping the pages was rather simple. One click in Photoshop, and the whole page was a mirror-image of itself. (Remember, we're dealing with illustrated pages at the moment, not the captions or speech bubbles - those come next.)

There were some pages where this simply could not be done. These were pages that included panels with illustrated text. For example, the first page of the comic includes illustrations of postage stamps. Flipping that page would have caused the text of the postage stamps to appear backwards!

For these pages, a more complicated approach was necessary, wherein the 'unflipable' panels had to get rearranged. Panels on the right got moved left, and panels on the left were moved right. Some individual panels got flipped, while others maintained their original orientation. The goal remained: to preserve a clear and easy reading flow for a right-to-left language, while also preserving the original orientation of the panels that had illustrated text.

Once this was accomplished, it was time for the lettering.

Step Three: Comics Lettering in HebrewSince the comic book translation largely followed the original, re-lettering in Hebrew mostly required replacing the English text in speech bubbles and captions with its Hebrew counterpart.

The first challenge we encountered was that Adobe software is notoriously clunky when it comes to right-to-left languages. Simply copying and pasting Hebrew text from a Word document would result in the letters arranging themselves in reverse order. Imagine copying the words "comic book" from one document, pasting it into another, and getting "koob cimoc" instead.

To fix this, I had to install an international version of Photoshop that had right-to-left language features... but even then, I had to manually turn on right-to-left properties for every single text box in the book. What should have been a simple cut-and-paste process turned out to be very labor-intensive.

The next step of the process required adjusting word balloons and captions to fit the new text. When you translate from one language to another, the resulting sentences are rarely identical in length. Hebrew, in particular, is a very economical language, so many of the sentences in the Hebrew version were shorter than those in the English. This meant that speech bubbles and caption boxes had to be adjusted - often shrunk - to fit the new text.

In addition, since some pages and panels got flipped, while others didn't, careful attention had to be paid to whether the reading flow was still working. Are we still finding a clear reading path from the start of the page to the end of the page? In some cases, speech bubbles and captions had to be moved around in order for the reading flow to work. Josh did most of the work here.

Step Four: Exporting as a Right-to-Left BookWith all of the new lettering complete, it was time to compile a PDF of the book to provide to e-book retailers and others. Luckily, this is an area where Adobe has things figured out. It was just a matter of tweaking a couple of settings, and the resulting PDF, when opened to 'two-page view', correctly places the pages in a right-to-left reading order.

Although many people don't read PDFs in two-page view, it's a great way to get a sense of how a comic book's "spreads" flow together.

The PDF also became the source file for e-books, such as the one that is available on Amazon.com. Generally, when you swipe to turn pages in an (English) Amazon e-book, you swipe from right to left, as if you were turning a page. For this Hebrew e-book, we had to make sure the settings were correct for a reverse reading order. If you read the e-book, you'll note that it does swipe left-to-right, in an action that matches what you would do if reading a physical Hebrew book.

The Result: A Comic Book in Hebrew!The process of translating "Brother's Keeper" to Hebrew was more labor-intensive and time-consuming than I expected it would be, but I am very happy to see that the book is now available to readers in Israel.

It's difficult to find publishers in Israel who would agree to publish a single-issue floppy comic, but the book is now available as a Hebrew e-book in Israel on several platforms, including Amazon.com and the popular Israeli book website, www.e-vrit.co.il. Direct links below.If you read "Brother's Keeper" in Hebrew, please let me know what you think of it! If you've also read it in English, I'd love your thoughts on the translation!

Where to Find Brother's Keeper in Hebrew and in English"Brother's Keeper" is available in Hebrew as the e-book שונמר אחי at the following sites:

Amazon (US & International) e-vrit (עברית) (Israel)"Brother's Keeper" is also available in the original English as an e-book here:

Amazon (US & International)While supplies last, physical copies of the book can be ordered here (US only, for now). Volume discounts are available for schools and other institutions. Contact for retailer pricing.

October 26, 2023

A Comic Book about an Old War... And a New One

My grandfather, who I knew as Sabba Yaacov, had very old wounds.

In May, 1948, early in Israel's War of Independence, he was part of the battle for kibbutz Ramat Rachel. That is where he was shot in the knees. That is why, when I was young and he was old, there were days when my grandfather's knees would hurt.

Several years ago, I turned my creative thoughts to my grandfather's stories. The story I chose to tell — initially as a short film script called "Brother's Keeper" — described his experience at the battle of Ramat Rachel, and in the makeshift field hospital in the basement of a monastery where his leg (and his life) would be saved.

I shared the script with my grandfather. He declared that although it was very much a 'Hollywood version' of events, he really liked it. In the years since, my grandfather passed away, and the script remains unproduced.

It sat on a hard drive for several years, until this summer, when an opportunity arose to collaborate once more with Joshua M. Edelglass, the illustrator of José and the Pirate Captain Toledano. I shared several story ideas with Josh, who immediately gravitated towards "Brother's Keeper". We decided we'd work together to reimagine the story as a single-issue (or 'one-off') comic book. The goal was to have something ready to debut in mid-November, at the Jewish Comics Experience, a new and exciting convention of Jewish comics at the Center for Jewish History in New York. So, in August, with only a few months to get the job done, I began to write.

I went back to old interviews that my uncle Yoav had recorded. My grandfather's accounts of the battle and its aftermath are riveting, and revealed surprising details that I had forgotten over the years. I also found this very detailed description of the battle. I drew from every account that I could find to create a composite representation of this small piece of that old war.

But I found myself facing a dilemma. What was my grandfather's story really about? Like most stories that are drawn from real life, it follows a sequence of events that took place without regard for message or meaning. The story was deeply compelling to me, but I wasn't sure why. It didn't seem to impart a lesson. It certainly wasn't expounding on war or saying anything profound about the human condition. It was just stuff that happened. Remarkable stuff, but not meaningful, as far as I could tell.

And I don't think my grandfather found it particularly meaningful, either. He loved telling these stories for the reactions he'd get, but he never concluded them with a moral or a lesson. For that reason, I felt comfortable to simply tell the story, without trying to force some profound meaning into it. In the book, my grandfather even admits, it's "just a story from a war."

Ramat Rachel is a small kibbutz on a strategically-significant hilltop just south of Jerusalem. In 1948, its residents found themselves surrounded on three sides by three very powerful Arab armies. The Egyptian army approached from the west, the Arab Legion came up from the south, and the Jordanian army, along with local Arab fighters, applied pressure from the east. They all wanted to drive the Jews out so they could attack Jerusalem from this high ground.

My grandfather was sent to help defend this kibbutz, and when that appeared impossible, he oversaw the evacuation and retreat.

When I wrote these scenes, they were fascinating pieces of history. It was hard to imagine an army attacking a kibbutz, with bullets and artillery shattering the bucolic quiet.

And then, I was confronted by the grim horrors of October 7, 2023.

What I wrote as history had suddenly become current-events. A terrorist army rampaging through Israel, attacking kibbutzim along the Gaza border. Residents, once again, forced to flee.

The book was already written, and Josh was working hard on the illustrations. For him, the experience was even more surreal. He was drawing an attack on a kibbutz while watching one unfold on the news.

Initially, all of this seemed like a horrible coincidence. "Brother's Keeper" is supposed to be historical. It's supposed to reflect on something that happened long, long ago. Never in my darkest nightmares did I imagine that it would become contemporary again.

And yet, here we are.

We continued our work on the book. With the Jewish comics convention about a month away, we had some hard print deadlines to meet.

But I felt as though the book we were working on had fundamentally changed. I wasn't sure exactly how, but it seemed suddenly more significant. A friend who stopped by for coffee one morning was able to articulate what I couldn't. When he saw a few of the illustrations, he declared, "we need this. Now!"

He went on to explain. Most of us weren't born the last time a kibbutz was attacked. Many of our parents weren't born yet, either. Part of the pain of the October 7 attacks was that we had never experienced anything like it before.

Then, my friend pointed at the illustrations I had shown him. He said "But we have been through this before. We've survived this before."

The moment he pointed that out, I realized that my grandfather's story was no longer "just a story from a war." It suddenly had meaning.

It wasn't the meaning I intended. It certainly couldn't have been my grandfather's meaning. How could we have imagined we'd need such a reminder again?

And yet, there it is.

My grandfather, surviving an attack on a kibbutz in 1948, reminds us of what we can overcome in 2023.

Josh and I had no plans for an immediate wide release of this comic book. We expected to print a bunch of copies to sell at the convention, and then to figure out a release plan from there.

But now, the story carries a new, urgent purpose. We are working very hard to make the book available as broadly as possible when it debuts in New York on 11/12/23.

To that end, I've set up an online store, where you can pre-order the book , especially if you can't make it to the Jewish Comics Experience to buy one in-person. We'll mail out the first wave of orders around the book's release date.

We're also making the book available at a discount for bulk orders, to make it easier for schools to utilize it. A friend is developing an educational guide that I will make available here to help educators incorporate the book into lessons about Israel's War of Independence and about the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Eventually, we hope to make the book available digitally through digital comics platforms. Plans are also in the works to release the book in Hebrew later this year.

While I hope that this book helps those who read it take some comfort and courage from its story, I remain painfully aware that a book cannot stop a rocket. It cannot defeat a murderous enemy. It cannot free a hostage.

And there is one particular hostage who I think about, who I pray will have the freedom to read this book some day. His name is Ofir Angel. He is seventeen years old — nearly the same age as my grandfather was in 1948. Ofir was kidnapped on October 7, while visiting his girlfriend in kibbutz Be'eri. He is from Ramat Rachel.

As of this writing, he remains in captivity.

I wish I could do more for him — for all of them — than write a book.

-Arnon

July 16, 2023

Tell More (Jewish) Stories!

There are only five short days before the launch of the biggest crowdfunding campaign of my career, an ambitious quest to raise funds for Maggid Magazine, a monthly publication of fun, all-ages Jewish comics for a broad and curious audience. In crafting our messaging around the project, we’ve been very particular about shaping a positive, proud message about the value of authentic, diverse Jewish stories in a pop-cultural medium.

I believe this message wholeheartedly. I believe that Jewish history, tradition and culture offer a ton of fantastic raw materials for crafting new, exciting, engaging and meaningful entertainment. As a creator who is not just Jewish, but well-versed in so much of our narrative tradition, I can’t help but feel a little bit obligated to share this amazing wealth of stories, characters and themes with the world.

It’s been invigorating to imagine all the fun we’ll have when this magazine is funded. Reinventing Jewish legends like the golem and the dybbuk, reframing popular genres through a Jewish lens, even drawing out the mythologies, folklores and characters of non-Ashkenazi Jewish traditions, which have been mute for so long without a voice in popular culture.

But every so often – too frequently these days – I am reminded of another reason that I am compelled to do this work. I write this with humility, and with quite a bit of absolute terror: If we do this work well, and get others to do it with us, we might save the world.

Whoa. Heavy.

World-saving is a common plot in superhero comics, but it’s rare that real people (especially ‘regular folks’ like you and me) have that kind of clout. So what sort of delusional narcissism is driving me to feel this way?

It all stems from a realization I had about six years ago, when I ran my last crowdfunding campaign for a certain short film about Jewish pirates.

“The Pirate Captain Toledano” was a unique project, the first narrative film to depict pirates as refugees from the Spanish inquisition, prowling the Caribbean for both survival and revenge against their oppressors. During the crowdfunding campaign, I spent a lot of time online, trying to find other people who took an interest in the unusual history of Jewish piracy. We Jews – for various reasons – hadn’t given this piece of our historical narrative much attention. But I bet you can guess who did.

I hadn’t gotten very deep into my “Jewish Pirates” Google search before I hit blatant anti-Semitism. Blog and social media posts co-opted our story and twisted it to their ends. Jewish pirates were not oppressed vigilantes fighting for justice in an unjust world. They were (according to these anti-Semites) “proof” of some sinister quality shared by Jews everywhere.

The evolution of the story of Jewish pirates offers a clear example of what happens when we neglect to tell our own stories. When we don’t tell our tales, someone else will tell them for us… often with ulterior motives, and to our great detriment.

It’s tempting to imagine an evil storyteller, hunched over a keyboard in some dark hovel, sniffing out the stories we haven’t told and warping them to some evil end… but I don’t believe that’s how this really plays out. I think stories emerge quite organically to fill a vacuum.

Living in a vibrant Jewish community, it’s easy to forget that there really aren’t many of us. Roughly 2% of the US population is Jewish. Globally, we’re only half a percent. In most parts of the world, there are no Jews, and where there are Jews, we’re quite rare. Most people on the planet have probably never met a Jew, and certainly have never had a meaningful interaction with one.

But we’re in movies, and we’re in books, and we’re on TV. We’re characters – often caricatures – squeezed through a narrow cultural definition of “Jewish.” I’m not even talking about the overtly negative stereotypes that were common in older narratives – Shakespeare’s Shylock and Dickens’ Fagin are by far the most well-known Jewish characters of classical literature. But how many times have you watched a crime show with a lawyer named “Goldberg”? How many times have you seen a scene where a character is rushed to the hospital and “Dr. Cohen” treats them? At first blush, it might seem that there’s really nothing wrong with these modern stereotypes. There’s nothing wrong with being a doctor or a lawyer. Those are impressive careers that require a ton of intelligence, not to mention years of training and hard work.

If you’re part of the 99.8% of the world that isn’t Jewish, and your impression of Jews is limited to these narrowly-defined depictions, you’re left with the unsettling sense that there must be something more to those Jews – something we aren’t being told about.

It’s a narrative vacuum, and it’s absolutely true. There is much more to Jews, Jewishness and Judaism than what people see on TV.

But nature abhors a vacuum – even a narrative one. Without thinking about it, people begin to fill in that blank space between the Jewish doctor and the Jewish lawyer. It might be something they heard once on the bus to school. Or it might be something they heard on an unscrupulous radio show. Often, people do what we all do when we stare too long into that dark closet in the middle of the night. They imagine monsters in the darkness.

Two summers ago, I took a trip to Mammoth Cave in Kentucky. At one point on the subterranean tour, the tour guide turned off the electric lights that illuminated the cave. For a few moments, we were plunged into pure, utter darkness, a black that was almost palpable. And then, the tour guide lit a match. Just one match, and we could see the entire vast cavern, and all seventy-odd people in the tour group.

It doesn’t take much light to dispel darkness. But we still need to strike the match. If a lack of authentic Jewish stories leaves a void in the popular narrative, we need to tell those stories.

We need to. It’s not optional. It’s an obligation.

That’s what this magazine is going to do.

But wait – I started off with a really brash declaration: that our work was going to save the world. Much as I feel strongly about Jewish stories making the world better for Jews, I recognize that’s not quite enough to warrant such a bold assertion.

How does the good we’re doing extend beyond us? How does it save the world?

If we can get this magazine to work – if it becomes a breeding ground for new popular fiction about a diverse and vibrant array of Jews and Jewishness – it can become a model for other cultures, races and creeds, too. If we can demonstrate a way to fill our own narrative vacuum, maybe others who face discrimination and hatred can learn to do the same for themselves.

Dispelling darkness can start with one match. It doesn’t have to end there. More matches add to the flame. More light dispels more darkness. You can’t imagine a monster in the dark when there is no dark.I would be remiss if I wrote all of this without sharing a link to the Maggid Magazine Kickstarter page. I invite you to follow the campaign, share it with your friends and when we launch on July 21, contribute what you can. And regardless of whether you contribute to, share or even just ignore the crowdfunding page, I beg you to tell more stories. Tell your stories – the ones we don’t get in movies or on TV. Tell your stories like the fate of the world depends on it. Because it does.

June 13, 2023

Rediscovering Serialized Publishing: From Dickens to Kindle Vella

With apologies to his fans and admirers, Charles Dickens put me to sleep. I had to read “Great Expectations” in middle school. Although I was a voracious reader at the time, I found it so ponderous that I couldn’t make it to the end of the book. It might have been the first (and possibly only) time I resorted to Cliffs Notes to get through a school assignment.

Someone explained at the time that Dickens was ‘paid by the word’, which meant that rather than crafting lean, efficient narrative, he was incentivized to drag things out. I don’t know if this is actually true, but at the time, it felt like a validating justification for my struggles with his writing.

What is certainly true about Dickens (and many other authors) is that he published many of his books in short bits and pieces, gradually, over time. This method of serialized publishing had been popular for a time, then faded. In a way, comic books took up the mantle in the 20th century, releasing long narrative arcs a couple dozen pages at a time.

The Resurgence of Serialized Publishing in the Digital AgeIn recent years, serialization has reappeared in the world of digital publishing. Platforms like Wattpad, Relish, Royal Road, and Amazon’s more recent entry, Kindle Vella, offer authors an opportunity to share their books with readers one chapter at a time.

From Comics to Novels: My Journey with Serialized PublishingExploring Serialized Publishing with "Ben Mortara and the Thieves of the Golden Table"I got my first taste of serialized publishing with my four-part comic book series, “Ben Mortara and the Thieves of the Golden Table” from Maggid Comics and Source Point Press. I enjoyed crafting the story, and grappling with the double-edged challenge of creating both a self-contained narrative arc and a gripping cliff-hanger for each of the four issues. And those four issues had to span a full and satisfying narrative arc, too.

With “Ben Mortara” rolling out to comic book shops (Issue #3 should be available in late June), I found myself looking for my next creative adventure. I found it in an old screenplay that had been gathering digital dust on my hard drive.

Reviving an Old Screenplay - "Wayfarers" - for a New Creative Adventure“Wayfarers” was originally a short film script. I wrote it more than a decade ago, and had hoped to find a way to film it in the desert and coast of southern California. The story, a Jewish post-Apocalyptic action-adventure inspired by the book of Exodus, follows a band of refugees as they race across a dystopian wasteland to try to reach the coast, where a freighter waits to ferry them to safer harbors. The short film script climaxes with a dramatic recitation of the Wayfarer’s Prayer – the first time I incorporated Jewish liturgy into a narrative. (Fans might recall the incorporation of the Friday night Kiddush in “The Pirate Captain Toledano”. And as you’ll see later this month, the Shema figures into issue #3 of “Ben Mortara.”)

Although I wasn’t able to make “Wayfarers,” the short script landed me a meeting with a veteran producer of action films, who encouraged me to expand the story into a feature. I churned out a first draft of a “Wayfarers” feature in a matter of weeks, and after a few rounds of revisions, the producer took the project out on the town, with me attached to direct. Eventually, “Wayfarers” captured the imagination of a French production company that had production facilities in Morocco. I was excited! They were talking about a seven-figure budget! Production in Morocco! I’d get to direct another feature!

But then, the notes came. Just one note, actually. They wanted me to make the screenplay less Jewish – or, better yet, not Jewish at all. They even suggested I make up a religion, since it’s science fiction.

The story is about a band of Jews who are fleeing persecution and fighting to maintain their identity. I wouldn’t make the change, they lost interest, and the project fell apart.

It’s been about a decade since I wrote the “Wayfarers” feature. In the intervening years, my biggest successes have been overtly Jewish stories – stories that did exactly what that French company was afraid to do.

So, a few months ago, as I was looking for another creative avenue to explore, I dug out the old “Wayfarers” script. With a writer’s strike looming, it didn’t seem like a good time to start shopping the screenplay around again. But I did begin to wonder how the story might come across in another medium. As a comic, perhaps? Or as a novel?

I began to write the “Wayfarers” novel without much of a plan for it. I wanted to see how it would feel to write straightforward prose again. For the last two decades, my writing has been a means to an end – screenplays are not the end-product, they’re blueprints for a film. Comic book scripts, similarly, are intermediary steps between story and product. A novel, on the other hand, is the end-product itself.

I found the process quite enjoyable, and before I knew it, I had a dozen chapters written. I began to think about what I might do with the book once it was completed.

The Dilemma of Traditional Publishing and Self-PublishingThe Lengthy Process and Uncertainty of Traditional PublishingTraditional publishing is, of course, an obvious option. But it takes a long time. And – to be vulnerably honest – I don’t know yet if my prose writing is any good! The thought of finishing the book in the hopes of eventually getting traditionally published took a lot of the wind out of my sails. It was too distant a dream, and too dependent on the whims of other people.

Navigating the Sea of Self-Published WorksSelf-publishing is always an option these days, but there’s so much self-published work out there, I couldn’t imagine spending the time and toil to raise my book above the noise. Self-publishing would also have to wait until the book was complete. I was impatient.

That’s when I remembered Charles Dickens. I had chapters written already – why couldn’t I publish those while I keep writing the book? I could publish the story gradually – one chapter at a time, like a TV show or a comic book series… or like Dickens! And I could begin to publish right away.

To me, serialization is a very exciting option. It gives me a chance to see how my work lands with an audience as I continue to write the book. It also creates deadlines, an artificial ‘kick in the pants’ to make sure I keep writing and get the book written. As a self-motivating solopreneur (which many of us are in the creative world), creating artificial, external motivation is really important!

Rediscovering Serialization: Choosing Kindle VellaThe Appeal of Kindle Vella: Familiarity, Clear Pay Structure, Potential Bonuses and Non-ExclusivityThere are numerous platforms for digital serialized publishing. Some, like Wattpad, have been around for a long time (in tech years). Some buy up rights and pay authors. Some are little more than blog sites that allow anyone to post anything for free.

I was surprised to discover the range of options. Until this exploration, I hadn’t even heard of this 21st century version of serialized publishing. But millions of people all over the world are reading their books in this way. Ultimately, I settled on Amazon’s relatively new serialization platform, Kindle Vella, for my book.

Vella has only been around for about a year and a half, and is only available in the United States at the moment. But for me, it had a few things going for it that caused it to edge out the competition.

I knew that as an Amazon product, Vella would have a familiar interface. I’ve used Amazon Video Direct and Amazon Media Direct to distribute streaming films and (back in the day) DVDs and Blu-Rays. I figured the Vella interface would be easy to learn. (I was right! It’s very straightforward.)

Amazon also had a clearer pay structure than most of the other platforms I considered. Readers buy ‘tokens’ from Amazon, and use those to unlock new chapters in the books they’re reading. Amazon then pays 50% of the value of those tokens to the authors. It’s not a lot of money, but considering other platforms don’t pay anything to authors, I felt it was the most reasonable deal.

And perhaps most importantly, although Amazon requires exclusivity (my content can’t be published elsewhere), that exclusivity is only for the first 30 days that a chapter appears on the platform. After that, I can re-publish the book anywhere I want (as long as that other place doesn’t mind the book being available on Vella, of course). This leaves the door open for a traditional book deal if the book turns out to be successful enough to warrant one.

After I started publishing with on Vella, I learned that Amazon also pays bonuses to authors. The bonus structure is much more opaque. No one really knows how Amazon calculates it, but the suspicion is that it has something to do with social interactions on the platform. When people “like” a chapter (Vella calls it an “episode”) or if they label it as their favorite at the end of the month, or if they leave comments or “follow” the book (to get notifications about new chapters), those all seem to impact the bonus that Amazon pays. I haven’t been on the platform long enough to see a bonus, but I’m curious to see if it’s a few cents, or if it’s a bit more substantial.

So far, the experience has been rewarding.

The Excitement of Serialized Publishing with Kindle VellaCollaborating with an Editor and Crafting Each ChapterBefore I publish a chapter, I send it to a friend of mine who agreed to act as the book’s editor (I’m happy to recommend her for anyone who needs an editor! She’s fantastic!) She sends each chapter back to me with her editorial markup, and I tweak those last few bits that require tweaking.

Posting a chapter to the platform is very straightforward. Vella offers an opportunity for authors to include a brief note to readers at the end of each chapter. I haven’t written a note for every chapter, but it’s been fun to think about this more direct form of communication.

So I posted the first four chapters and let things run to see how they’d go. The first three chapters of every Vella story are free. Chapter four and on require ‘tokens’ to unlock.

It’s been one week. Here’s what I learned.

Promoting and Observing Initial Reader EngagementUnlike the Amazon’s video platform, there’s no delay in Vella’s statistics. When I check the dashboard, I can see exactly (and up-to-the-minute) how many people read each chapter of my book.

In the first day, I did hardly any promotion at all. I wanted to see how much organic traffic would come to the book through the platform.

No one found it.

This was a risk I took knowingly. As a newer platform, Kindle Vella has a considerably smaller audience than some of the more established platforms. And of course, as an algorithm-driven platform, it’s more likely to recommend titles that have a track record. I’d have to ‘prime the pump’ a bit before anyone might discover the book on their own.

The Challenge and Motivation of Daily Statistics ResetsWhen I began to promote the book on social media, it was exciting to see the first trickle of readers sample those first chapters. It was even more exciting to see readers get to chapter 4 and ‘unlock’ it with their tokens. Bit by bit, as word spreads, the numbers on the dashboard improve.

But the Vella dashboard has an interesting quirk: The primary display shows readership statistics from today only. So every night at midnight, all the numbers revert to zero. Every day is a new opportunity to draw new readers in.

Sometimes, that zero can feel very discouraging. When I need a boost, all it takes is a few clicks and I can see the “all time” statistics – every reader, every chapter, since the book was published. But most days, I see that zero as an exciting challenge. (See above, regarding self-motivation for the solopreneur!)

Yesterday was my first ‘new chapter’ day. Chapter 5 was made available on the platform sometime around midnight. I was happy to see that some of the people who ‘follow’ the book to get updates about new chapters went in and read it (which means they ‘unlocked’ it with their tokens). Eventually, as more people ‘follow’ the book, I’ll hopefully have a predictable flow of initial readers for each new chapter.

Balancing Promotion and Writing: The Journey ContinuesKeeping the Story Flowing While Engaging with ReadersBut while I’m promoting the book and watching readers check it out, I still have to keep writing! I’ve got enough content written for the next several months, but I’m only halfway done with the book itself. I try to churn out around 500 words per day – a modest goal, but more than enough to keep me on track to finish the last chapter before it needs to go up on the platform.

Join the Journey: Explore "Wayfarers" on Kindle VellaIf you’d like to check out Kindle Vella, maybe check out a few chapters of my book, start here:https://www.amazon.com/kindle-vella/episode/B0C758RNCN

And if you do like the book, don’t forget to do all those important things:

- “Like” each chapter!

- Leave a comment in the chapters you like!

- “Follow” the book to get notified of new updates!

- Review the book (those 5-star reviews really do mean a lot!)

- At the end of the month, when Amazon asks you what your favorite Vella ‘episode’ was, pick one from “Wayfarers!”

December 19, 2022

Ben Mortara - My New Comic Book Hero!

I'm thrilled to introduce my new comic book series called ",Ben Mortara and the Thieves of the Golden Table" from Maggid Comics and Source Point Press!

This series is a thrilling adventure story that blends contemporary archaeology with a fantastic world of ancient Jewish folklore and mythology. The story follows globetrotting archaeologist Ben Mortara on his mission to recover the legendary Golden Table of Solomon, an ancient artifact with unusual and valuable powers. Along the way, he gets help from a host of memorable characters, including a devout Afghani 'fixer', an Israeli antiquities sleuth, and a mysterious, ultra-secretive benefactor.

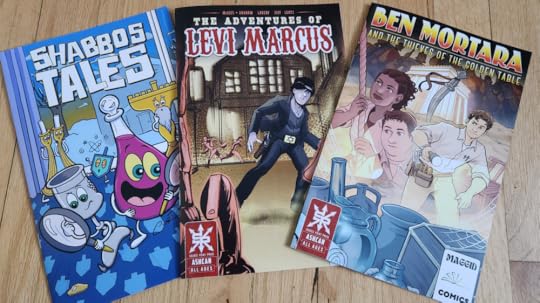

I created this exciting new series with the talented team at Maggid Comics, a new imprint of Source Point Press. The brainchild of Ramy Dubrow and Dave McLees, Maggid is leading the charge to create great Jewish comics for all audiences. I've been working with Source Point since August to help launch Maggid Comics, and am now the imprint's "interim editor-in-chief". This month, we're introducing several comics series, including "The Adventures of Levi Marcus" about Wyatt Earp's gunslinging Jewish nephew, "Partisan 42", a supernatural action thriller set in Europe during WWII, "Shabbos Tales", a kids' series in which anthropomorphic Judaica objects have madcap adventures in the 18 minutes before sunset on Friday, and "Reb Meilech's Tales", a compilation of the Hassidic-inspired stories of Reb Meilech Dubrow, OBM.

In "Ben Mortara", we're launching a fantastic world with an exciting mix of adventure, fantasy, and Jewish history. I've written the series for both comic book fans and those who are new to the medium. It's meant to be an ideal starting point for anyone looking to explore Jewish history and folklore in a fun and entertaining way. I hope you'll join me for this thrilling adventure and help Ben Mortara in his quest to reveal history's mysteries!

The first "teaser" issue of "Ben Mortara and the Thieves of the Golden Table" is out now and available at ,www.maggidcomics.com. Issue 1 of the series will be available where comic books are sold in March, 2023.

December 6, 2022

How to Use Scrivener for Comics Writing

Over the last few years, I've stumbled into a new creative skill: writing comics and graphic novels. When I started writing "José and the Pirate Captain Toledano" - my first graphic novel - I had no comics writing experience, but I knew a lot about screenwriting.

I write my screenplays using screenwriting software. The software I use (Final Draft, WriterDuet or Scrivener - depending on the project and its needs) does a lot of the formatting for me, so I can focus my entire creative energy on crafting the story, and not on whether or not the margins are set correctly.

When I started comics writing, I wanted to find software that could achieve that same automation for a comics-format script. That's how I started using Scrivener to write comics.

Using Scrivener to write comics isn't completely intuitive. There are several steps to take, and several tricks I've learned along the way to make the process work more effectively. Here's how I set up a new comics script in Scrivener:

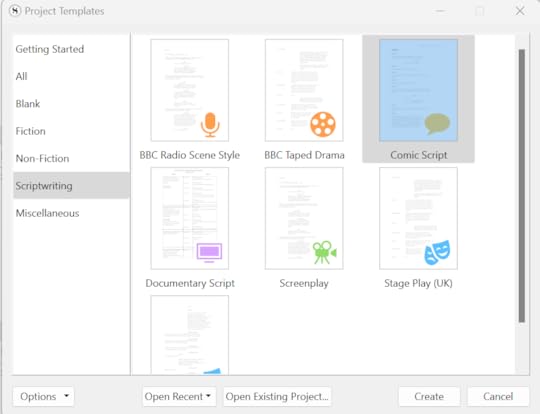

Step 1: Selecting the Comic Script TemplateWhen you launch Scrivener for the first time, it prompts you to create a project. If you've used Scrivener for other projects, it may open the most recently-launched project first. If that's the case, select [FILE] and [NEW PROJECT].

In the window that pops up, you'll see a whole bunch of possible script and book templates to choose from.

On the list on the left, select "Scriptwriting".

You'll see a bunch of script format options. Select "Comic Script" then hit "Create"

Step 2: Creating the Project File

Step 2: Creating the Project FileOn the next screen, you'll be prompted to create a name for the project, and to select a location on your computer where the project will be saved.

Note: Scrivener projects aren't just one file. They're an entire folder that holds multiple files. This is because Scrivener isn't just a word processor. It's an entire organizational system for writers.

After you've selected the file location and hit OK, you'll see the main Scrivener interface.

On the left-hand side of your screen, you'll see a column. There's a lot to explore here, but we'll focus on the stuff that's specific to comics writing.

IN CASE YOU'RE CURIOUS: Setting up your Title Page and Updating Author and Project MetadataYou don't have to do this step now - but some of you might be wondering about it, so I include this tangentially for you. Skip ahead to Step 3 if you don't want to worry about your title page yet.

On the left side of your screen, click on "Title Page"

You'll see in the center of your screen a default title page with several sections in , and a few in [square brackets].

Go ahead and replace any of this with whatever you'd like. BUT: Anything in can be edited globally (see below)

Generally, you should update all of this metadata information only when you're ready to compile a finished script. The reason for this is a little silly, but I'll explain in a bit.

To replace metadata tags like and other custom tags on your title page, do the following:

Go to [FILE]->[OPTIONS]

Under the "General" tab, select "Author Information"

Fill in the information that you'd like to appear on your script's title page, then hit "OK".

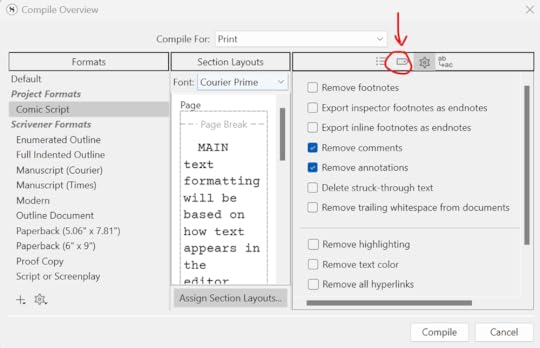

Next, click [FILE]->[COMPILE]

On this screen, click the little "Metadata" button. It's a bit hard to find, so use this image to guide you.

"Title" here will replace a metadata tag that may appear elsewhere in the document, such as on the title page. The metadata tag currently looks like this:

Once you put your own book or series title into this form, it will automatically replace in the document when the book is compiled.

Once you've filled in this information, click the ab->abc button (to the right of the gear icon). Here, you can put in an issue number, if your book is part of a series.

Here's why you need to wait 'til the end to do this step. There is no "OK" button! If you hit 'cancel', your changes are lost. You need to hit "Compile" for the changes to take effect. It's an odd quirk of the software for which I have no explanation.

In my experience, it takes a few tweaks to the metadata before I'm happy with the way the title page looks after I compile the document. You might just find it easier to edit the title page manually (but be aware there are also headers and footers that use this data. A bit of experimentation may be in order... before you fine-tune your project to your satisfaction.)

Step 3: Understanding PagesScrivener is not a WYSIWYG ("What you see is what you get") word processor. It's designed to organize and break down the writing process for you.

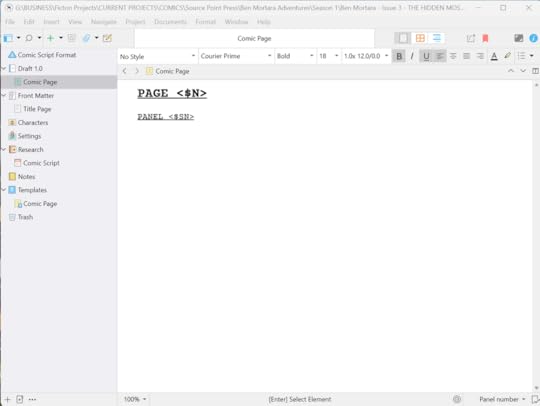

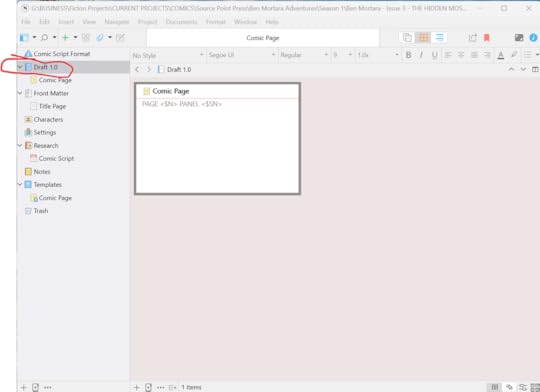

On the left side of the screen, in the column with a folder-like structure and icons like "Comic Script Format" and "Front Matter", you'll see an object called "Draft 1.0", and underneath it, an object labeled "Comic Page". This is a 'sub-document' - a part of Draft 1.0.

Click on "Comic Page" and you'll see in the main screen a blank comic page with a couple of metadata tags.

These metadata tags will be replaced when you compile your document with the actual page and panel numbers. This is one of the powerful ways in which Scrivener automates comic script formatting and saves lots of time and headache.

When you hit a carriage return to start a new line, hit it again to open a list of formats. Select "Panel number" to create a new Panel tag, or "Page number" for a new page tag.

Similar to screenwriting software, you can use TAB to cycle into Character, and from Character hit ENTER to switch to Dialogue, etc.

Play around with it, find the shortcuts that work for you.

You could write your whole script in this window, in this very document. But if you do, you might be missing out on one of Scrivener's most powerful features.

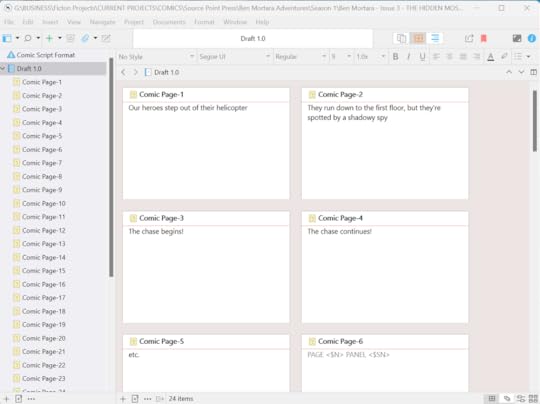

Step 4: Setting Up your PagesClick on "Draft 1.0" in that left column. It will take you to a new view of your project. Sort of like 'index cards'. But for now, there's only one card - the 'comic page' we started out with.

Like any index card, you can add text to this one, describe the scene that should appear on this page.

One of my favorite ways to use Scrivener for comics writing is to actually create a separate sub-document for each page of my comic book or graphic novel.

I right-click the comic page 'index card' and hit 'duplicate'.

I do this as many times as there are pages in my book. In this case, it's a regular issue floppy. The story is going to fill 24 interior pages, so I create 24 'index cards'.

Notice that all of these pages are now individual sub-documents in that column on the left.

Step 5: Adding Story Information to the Index Cards

Step 5: Adding Story Information to the Index CardsYou'll see in the image above that I started filling these 'index cards' with bits of the story I'm going to tell. I'll often take my synopsis or story treatment and copy sentences directly out of it and paste them in here. It's a great way to plan out where my story beats will land and how many pages they'll take up.

If a scene requires more than one page, I'll copy the synopsis into multiple index cards - I might put (1 of 2) and (2 of 2) at the beginning of each index card that describes a two-page scene. Or I might break up the synopsis of that scene into two parts across two cards.

Once you've done this for your book and filled in the 'index cards', click on your first page in that left-hand column.

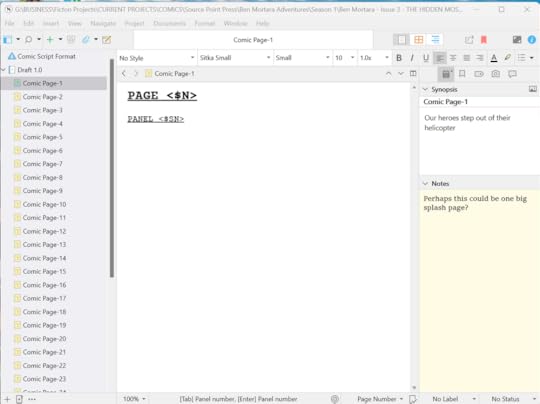

Step 6: Adding Notes and Bringing it All TogetherWhen you're looking at your blank first page, click the little blue 'i' in the top-right corner. It opens a window called the "Inspector", where you'll see the synopsis that you wrote into your index card.

You'll also see a 'notes' panel. It's yellow (perhaps to remind us of those old reporter's notepads?) It's a great place to jot down additional notes or ideas for a scene.

If you keep this panel open as you write, you never have to 'flip back and forth' between the page you're working on and your outline or synopsis document. It's all right in front of you!

Breaking a script down into individual pages like this is my favorite feature of Scrivener for comics writing because of the way it allows me to organize and access only the notes I need for that page.

If you'd like to give Scrivener a try for your comics writing, you can download it from the Literature and Latte website. (This is not an affiliate link - L&L doesn't give me anything for referring you, and I haven't received anything for writing this blog article.)

If you'd like to read some of my comics, check out "José and the Pirate Captain Toledano", or pop over to the Maggid Comics website (it's still in development as of this writing) and find my new books there.

November 16, 2022

A Screenwriter's Contest Strategy to Keep you Sane

Several years ago, I wrote a popular blog post about how to use (and not overuse) The Black List (www.blcklst.com) as part of a screenwriting self-evaluation and marketing strategy.

Since that post, new tools have emerged and evolved that have changed the way I approach the process of getting attention for my screenplays.

Although Black List evaluations may occasionally play a role, I now mostly rely on a constellation of coverage services, screenwriting contests and the submission portal Coverfly (www.coverfly.com)

The First StepMy first step is to make sure the writing is good enough. Those entry fees add up, and if my scripts don't place well, I get no value out of that 'investment'. So instead of wasting money on entry fees to 'test' my screenplay, I spend a bit more up-front on script coverage or notes.

Sure, I also get notes from friends, but the real test is to get feedback from people I don't know (so I know they're not going to 'try to be nice' when they should tell me what's actually wrong with my script!)

The Black List is the cheapest option for quick-turnaround evaluations of your writing. (See my blog article if you're cash-strapped and need to use the lowest-cost option for initial feedback.)

After really enjoying that service, I've found over time that the quality of the notes and the value of the rankings wasn't quite as high as I had hoped it would be. Now, instead of The Black List I use a range of coverage services from Indie Film Hustle, WeScreenplay, Shore Scripts, and others.

The coverage I get from these services is more expensive, but it's also more comprehensive than the stuff that comes from The Black List. It's a good way not just to find out if my screenplay is good enough, but what I might consider improving before submitting the screenplay to competitions.

What is Screenplay Coverage?At its core, coverage is feedback. You send your script to a coverage service, pay them a bunch of money, and they have an experienced reader read the script and write feedback about it. The feedback may include a synopsis of the story (which can be a useful way for you to test if your intended story actually comes through) and specific notes about what works and what doesn't in your writing.

Some coverage services also offer notes on the market potential for your script - is it better-suited to an indie producer or to a big studio?

Many coverage services also provide a "score" which usually boils down to three 'grades' - PASS, CONSIDER or RECOMMEND.

You want your script to get a RECOMMEND before you start submitting to competitions.

Screenplay Coverage StrategyLike with The Black List, coverage services can be inconsistent. One reader might love your script. Another might hate it. For that reason, I rarely trust just one evaluation. When I have a draft that feels ready, I usually submit to at least two coverage services to see what sorts of feedback I get. I don't submit to screenwriting contests until I get at least one RECOMMEND and one CONSIDER.

If the script doesn't get the high scores it needs, I take the notes and revise the script, then I submit for more coverage.

Once I have the RECOMMEND and CONSIDER (or two RECOMMENDs - even better!) I submit my screenplay to the contests.

Which Screenplay Contests should I Submit to?It's hard to know which screenplay contests are worth the fee. At the end of the day, none of them are worth anything if your screenplay isn't good enough.

But if you've tested your writing with coverage, and you're ready to submit it to competitions, consider a few guidelines.

There are lists of 'top screenwriting competitions' out there. Don't take any one list as gospel! Look at several lists, and see which contests come up multiple times. I won't recommend any here that I haven't personally had good experiences with. (So if I don't list a contest here, it might be awesome - I just haven't experienced success there yet!)

I used to think that the top contests were the ones where the winners got the biggest prizes. That's not necessarily a good rule of thumb. After all, there's usually only one winner, and there can be thousands of applicants.

The thing to look for instead is how the festivals treat their finalists (and, in some cases, semi-finalists). If you're lucky - but not lucky enough to win the screenwriting contest lottery and land at the top - you'll find yourself rising to "finalist" in some of the contests to which you apply.

Here's what to look for:

Who's Reading?The first couple of rounds of a screenplay contest are read by 'readers' - nobody who can actually do anything for your career. But at many of these competitions, the finalist round is read by people who can actually do good things for your career - you want them to read your work and love it, so that even if you don't win, they still reach out to you to discuss it and maybe help your work along somehow. Most good contests will list (or hint at) who's reading the finalist screenplays, so check their websites!

The Page Awards is very good example of how this works. As a Finalist, my screenplay was read by top literary agents and managers. Although I didn't win, one of the managers who read my script even reached out to me after the competition and asked for a meeting to learn more about what I write.

Additional Support?The best screenwriting competitions offer significant support to their finalist screenwriters (and not just to the winners). This may include sending out loglines to their industry contacts, offering to set up meetings, making introductions, etc.

I got to experience this first-hand when my PAGE finalist script hit the Launch Pad top-50 (that's their 'finalist' level). Since then, there's a guy at Launch Pad who emails me once every few months to see if there's anything he can do to help my career along. He has submitted my screenplay to agents and managers, and has tried to facilitate meetings on my behalf.

These are the contests you want to submit to - the contests that actually work to get high-scoring screenplays into the hands of the right people.

The Critical Keystone to the Whole Screenwriting Contest StrategyTher is one more important (nay, critical!) piece of the strategy:

As much as possible, I submit to these competitions using Coverfly. Ditto (and in some ways, more importantly) for the coverage services.

This is because Coverfly aggregates the results from all these contests and coverage scores and uses that to rank my screenplays in comparison to all the other screenplays that use the service.

What is Coverfly?At its core, Coverfly is a "common application" website for submitting screenplays to screenwriting competitions. What differentiates it from typical 'common application' sites is that Coverfly tracks your script's progress, assigns it a score based on its performance in the competitions, and ranks it in comparison to other screenplays on the Coverfly service.

How do Coverfly Rankings work?High-ranking scripts may appear on Coverfly's "Red List." Getting Red-Listed might feel nice, but it doesn't mean too much, as the Red List is subdivided into a zillion categories and several timeframes. I've had screenplays in the top-20 for "Sci-fi feature of the month" or "western feature of the month" for numerous months over the last several years.

The harder "Red Lists" to hit are the ones that measure top-performers over the course of the year. "Top sci-fi screenplay of the year" is a much harder bar to meet. "Top screenplay of the year" is even harder.

Coverfly also offers an overall ranking, as compared to all other screenplays on the platform. Currently, I have scripts in the top 1%, 4% and 7%. Top 1% means something. People have seen the script on Coverfly and have reached out to me about it. The rest of the rankings are nice, but those scripts need to perform a little better in order to get serious industry attention.

Other Coverfly BenefitsScreenplays that are listed on Coverfly can be made available to readers. For high-ranked scripts, this can be a great way to get additional exposure. My highest-ranked scripts have been read numerous times by executives and reps who browse Coverfly for new talent.

But Coverfly makes an effort to create more opportunities for its top-scoring writers. Last year, Coverfly selected one of my screenplays for a professional virtual table-read. They hired actors and set up a really impressive presentation, and gave me the opportunity to invite reps, producers and industry friends to sit in on the performance of my script.

They also routinely give high-ranking writers opportunities to pitch their scripts to industry insiders - a level of support and access that is otherwise very hard to get.

Putting the Strategy TogetherIt starts with Coverfly. I upload the script to that platform, add in all the info that the platform asks for, and prepare to submit the screenplay to coverage services.

When coverage comes back with at least one CONSIDER and one RECOMMEND, I begin to submit the screenplay to competitions.

At this point, since I get the coverage through Coverfly, good coverage scores begin to push my Coverfly ranking up. A "Recommend" might put a screenplay somewhere in the top-20% or so. (But don't brag about this - nobody cares about top 20%. The vast majority of those screenplays won't see day one of production).

I use Coverfly to submit to the screenwriting competitions that I've heard good things about - contests with a strong panel of readers who will read the finalist-level submissions, or who have a strong track record of continuing to promote and support top-scoring writers and screenplays.

As those results come in and my Coverfly ranking increases, I can use that ranking along with contest results as a talking point when pitching my screenplay. As an example, when I tell people about "Out of the Sky", I can describe it as "a PAGE, Launch Pad and Vail Finalist that's currently a top-1% screenplay on Coverfly"

How much does all of this cost?Fortunately, the Coverfly service is free to screenwriters. But everything else does add up.

Coverage can cost anywhere from $99 on the ultra-cheap end to several hundred dollars.

There are screenwriting contests with no fee, but most will charge anywhere from $20 to $99 (depending on the contest, and on whether you hit the early or late deadlines)

I keep a spreadsheet to track my submissions - a separate spreadsheet for each project. I keep track of the costs in that spreadsheet, too. This helps me make sure I'm not throwing good money after bad on a screenplay that simply isn't ready yet.

Generally, I've been spending a little over $1000 on this process per screenplay, spread out over the course of about 6 months. That's $400-600 on coverage services, and the rest on screenplay contests. If a screenplay consistently places in contests, I might spend a bit more on it to submit it more broadly. If it doesn't seem to be doing well, I hold off on more submissions until I figure out how to improve it.

Yes, it's a lot of money, but once I sell even just one of these screenplays, it'll pay for all the contest and coverage fees I've paid over my entire career. And it's cheaper than graduate school.

More than one way to skin a cat...I'm sure there must be many ways to approach the early-career screenwriting game. I certainly won't pretend that my approach is better than anyone else's. In fact, if you do things differently, and you think there's something you do that could be helpful to people, please share in the comments below!

Happy writing!