Arnon Z. Shorr's Blog, page 3

March 22, 2021

Aspect Ratios and Visual Storytelling in Zack Snyder's Justice League

Today, a quick review of ASPECT RATIO as a storytelling tool. This isn't new material for me (I covered it in some depth in this StudioBinder video) but with debate recently re-invigorated by a controversial re-release of a director's cut of a superhero film flop, it seems like a good time to revisit the topic.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T0YHA2yxCwMWhat Brought "Justice League" Back?This is relevant! I promise!

Since the release of director Zack Snyder's ill-fated "Justice League", there has been a clamor among his fans to "release the Snyder cut". Apparently, Warner Bros. released an unintelligible fragment of what fans believed was the director's much more robust and artful movie.

The Snyder Cut is a four hour monster of a movie. There was no reason for Warner Bros. to spend time or money on a re-release. And they said so - many times.

Fast-forward to the COVID-era. Warner Bros. and HBO were in trouble. HBO MAX, a new streaming platform, was about to launch. Streaming platforms do well at first when they have a large library of content - not a problem for Warners and the Home Box Office. But they can't sustain new subscriber levels unless they offer something new. When COVID hit, Hollywood production ground to a near-standstill. Creating new content became nearly impossible for a while.

So they rooted around in the trash bin, found the bits and pieces of "Justice League" that had been discarded, and repackaged them as "new content" in order to appeal to subscribers on their new small-screen platform. ("Small screen"... remember that... it'll matter...)After the initial shock of the film's four hour running-time (and the fact that - despite the hype - it's really just mediocre), the biggest complaint I've seen about the film is about something technical that most people don't pay attention to: its ASPECT RATIO.

What is Aspect Ratio?An aspect ratio is the ratio of the height and width of a film's frame. Most of the films we see today are shot in a fairly wide aspect ratio, ranging from roughly 1.78:1 at the narrowest (also referred to as 16x9 - the ratio of high definition television) to 2.66:1 at the widest (the far end of what is colloquially referred to as "scope" or "Cinemascope") 1.85:1 and 2.35:1 are very popular aspect ratios for movies.

But the Snyder Cut of "Justice League" is presented in a much narrower aspect ratio than any of these: 1.33:1, also known as 4x3 - the aspect ratio of old televisions, and very similar to the 1.37:1 "Academy Ratio" of old Hollywood movies.

Many of the complaints I've seen come down hard on the aspect ratio itself, as if 1.33 is somehow a "bad" aspect ratio for a movie.

I actually directed a feature film in 1.33, so I can tell you from experience, there's nothing wrong with it!

Aspect Ratios and StorytellingIt used to be that a film's aspect ratio was an accident of technology. Film cameras recorded images in a particular rectangular frame, and that's the frame you got to work with as a filmmaker.

This changed most dramatically in the '50s, as Hollywood began to compete with television for American eyeballs. The studios employed different types of lenses and film to create wider images - images that could not be reproduced satisfactorily on a TV set in a living room.

This is an important point, as we'll come back to it later in the article!

In the second half of the 20th century, filmmakers had increasing options for their films' aspect ratios. Rather than being 'forced' into a ratio, it became something filmmakers could choose before the start of production.

I heard a story once about the great cinematographer, Janusz Kaminski. He was asked how he chooses the aspect ratio for the films he shoots. His response, roughly: "If it is about grand landscapes and big chase scenes, I shoot in a wide format [so, some version of "Cinemascope" - 2.35:1 or wider], and if it is about tall monsters or dinosaurs, I shoot in a taller format [so, 1.85:1 - a favorite of Spielberg's first few decades]."

In other words, the aspect ratio of a film dictates how the action or images on the screen are presented to the audience. It makes a difference - sometimes a profound difference - in the way the story is told.

Christopher Nolan (notably: an Executive Producer of "Justice League") takes this to another level, routinely changing aspect ratios within a film - going from a wider screen in action sequences to a taller screen for dramatic moments. Often, in Nolan's films, these aspect ratio changes can only be seen in IMAX theaters - the taller frames are cropped for smaller screens. (See "DUNKIRK" for an example of this).

Why Use 1.33:1 Aspect Ratio?The old television aspect ratio of 1.33:1 is hardly ever used in movies, even though it is very similar to the "Academy Ratio" of Hollywood's first Golden Age.

Once audiences got used to the wider formats, they came to expect those wide images in theaters. In fact, many new filmmakers will shoot their early films in very wide formats, just so they come across as "more cinematic". This isn't always the best choice for the story, but such are the mistakes beginners make.

But 1.33:1 has its place. Sections of "The Blair Witch Project" were presented in 1.33:1. This was both to preserve the home-video and indie documentary feel of the movie, but it also served a storytelling purpose. A 1.33:1 frame tends to make close-ups very dominant. There's very little room to see beyond or around the face. In contrast, a close-up in a 2.35:1 frame often fills less than half of the screen, leaving plenty of room for the scenery, or for other characters.

In a claustrophobic horror film that's all about scary things that exist just outside the frame (like "Blair Witch"), an aspect ratio that doesn't allow us to see around our close-ups makes those scenes all the more intense.

When I used 1.33:1 in a feature film called "Glimpse", it was for a similar reason. The film is about a police detective who's stuck at home while his department investigates the suspicious circumstances of his wife's death. Since he's stuck at home the whole time, I wanted to convey that sense of claustrophobia, of the walls closing in. So I hemmed in my film's characters in a claustrophobic 1.33:1 format.

"Glimpse" played a few film festivals and won awards for what was seen as a 'daring' use of the aspect ratio. But when it came time for release, the old feeling that "1.33:1 isn't for movies" reared its head. To this day, the only version of "Glimpse" that you can see is presented in a wider aspect ratio.

What Went Wrong with "Justice League"?If there's nothing inherently wrong with 1.33:1 as a cinematic aspect ratio, why all the complaints about it in "Justice League"?

I'll be honest, I think it was a poor choice.

I've left a few clues along the way. Let's piece them together.

Remember how the studios in the '50s started using wider aspect ratios as a way to drive more cinema-going? Truth is, it's still happening, but now that TVs offer wide screens, it's happening in other ways.

In this case, IMAX is the culprit. The format offers filmmakers the opportunity to shoot on very high-resolution cameras, and for the films to be screened on enormous cinema screens. The IMAX aspect ratio is 1.43:1 - very close to the 1.33:1 or 4x3 of "Justice League". In fact, Snyder has admitted that his preferred exhibition method would have been IMAX screens, had the pandemic not gotten in the way of a theatrical re-release.

But the pandemic is the reason the re-release happened at all, and it's because of a need for small-screen content.

And here's where everything derails. If Snyder framed his scenes for IMAX, he meant for them to be seen on a screen that is so large, it extends to the farthest corners of our field of vision. When we watch a movie on an IMAX screen, we generally can't take in the entire frame in one glance. We create our own 'frame', guided by the focal points of the image before us.But what happens when you take an IMAX frame and shrink it down to fit in a domestic television set? Remember wide formats like "Cinemascope"? They were pushed by the studios as a way to give people an "only in theaters" experience. IMAX is like that, too. A film framed for IMAX simply won't have the same effect on a small screen.

Of course, the 1.43:1 aspect ratio can (in theory) work fine on small screens. After all, it' so similar to TV's old standard 1.33! But there's a big difference between framing a scene for a television set that fits comfortably within our field of view, and framing a scene for an IMAX screen that extends beyond our field of view. The same frame that forced us to engage, to find the focal points of the image, to 'frame' it ourselves, no longer compels us. Whatever life it may have had on the huge screen is diminished by the fact that we can see the whole thing in one glance.

Snyder's original intent was not to make a TV movie. He framed his scenes for an IMAX screen - and that might have been the right way to go for a theatrical release. But when the "Snyder Cut" was resurrected, it was always a small-screen ploy.

And Snyder could have adjusted for it.

Hollywood films are shot to 'protect' for other aspect ratios. Most movie theaters don't have IMAX screens, so films are shot in such a way that wider aspect ratios can be cropped out of the larger IMAX image. Even if Snyder's cut of "Justice League" had made it to theaters when the film was first released, most of those theaters would have shown a cropped, "wide" version of the film. Only IMAX screens would have shown the "taller" aspect ratio.

My little indie film was shot in the same way - we framed the action for 1.33:1, but made sure a wider 1.85:1 aspect ratio would be possible within those frames. When the film was released on streaming platforms, it was the wide aspect ratio that reached audiences.

It's tempting to brand this Snyder's mistake. Or HBO's. Or Warners'. They could have released "The Snyder Cut" in the same wide-screen ratio that they would have used in non-IMAX theaters.

But that's a bit like suggesting that "Lawrence of Arabia" should have been cropped on VHS. Ick! "Pan and scan", the method by which wide-screen movies were re-framed for 4x3 TVs, was a terrible thing for cinema.

Really, the mistake is ours - it's our fault for expecting anything like an IMAX experience on our small home televisions.

I'll be honest. I really disliked "The Snyder Cut", and generally haven't responded well to most of Snyder's films. But at the end of the day, I don't think we can judge the aspect ratio fairly until we see it at its intended scale.

February 25, 2021

Invest in your Voice

Not long ago, I heard a piece of pithy advice from none other than Ben Feingold, the CEO of Samuel Goldwyn Films. He offered this nugget of wisdom during a virtual panel discussion of film/TV executives. I had helped organize the event with the Brandeis Alumni Arts Network, and had the honor of presiding over the Q&A. The question that I posed to the panelists was about how to reach them. What's the right way (and what are the wrong ways) for an aspiring writer, director, actor, producer, etc. to get their attention? Among the various responses was Feingold's:

"Invest in your voice!"

Although Feingold didn't elaborate much, the basic idea was this: when you talk to the folks in power, make sure you can show them why you're worth their time and attention. And the thing that makes you worth more than anyone else is whatever makes you you. The particular constellation of perspectives and experiences and attitudes and approaches that differentiate you from anyone else.

This line struck me like a thunderbolt. For the last several years (and particularly during the COVID era), I've spent a lot of time writing new screenplays, refining my 'brand' and updating my website and social media to reflect an image - an image that I first had to grapple with and unpack. At the heart of much of this work was an effort to clarify - both to myself and to others - my "voice". Until I heard Feingold's advice, I didn't really have a way to name all the work I had done. Now I do: "Investment".

"Invest in your Voice" is advice I wish I had received two decades ago. I'm sharing it here in the hopes that it reaches some of you earlier in your careers - early enough to make the greatest possible difference. Of course, such a short phrase can mean many things to many people. Here's how I understand what "Invest in your Voice" means.

The Raw MaterialsWhat is "Voice"? For a screenwriter, it might be the way that you unpack a scene or reveal characters - a way that is unmistakably your own. For a director, it might be the way you frame a certain type of scene, or the way you light your characters. Whatever it is, it's the thing that makes it possible for people to recognize you in your work.

It can be very difficult to figure out your voice. I was only able to do it for myself after making dozens of films and writing a whole bunch of screenplays, and then asking the question, "why did I tell all those stories? What was I trying to achieve?" The common denominator, the thin thread that strung all of my work together? That's voice.

So what does it mean to "Invest" in this type of voice? To invest in the raw materials? It means digging. Mining. Delving into yourself with as much honesty as you can muster and finding a way to articulate what you find. For some of you, it might mean writing a lot, creating a lot, and then stepping back and evaluating what the common threads are.

This takes time, and it might even take money. Therapy can be helpful here, as can some creative coaches, workshops, books, etc. That's what it means to invest. Don't assume it'll just hit you one day. Go looking for it.

If Feingold's advice isn't strong enough for you, consider something Steven Spielberg once said (I believe it was at a commencement address, but might have been another context). He said that the most important thing a creative person can do is to know his or herself very, very well. Know who you are! That's what makes you unique! That's what will make your work valuable!

Craft and CreationKnowing your Voice isn't enough. You've got to use it, to draw it out, to express it through your work. For a writer, this means writing. A lot. Every day, if you can manage it. For a director, it means directing - in any way you can. More importantly, it means creating with your voice in mind - don't just tell stories, tell your stories.

This is why investment is important. When we start out, we're lucky to get hired to tell any story at all. It's tempting to hop from job to job, from gig to gig, picking up scraps and experience along the way... but these gigs rarely give you an opportunity to really express yourself.

To apply your voice. You need to create opportunities for your voice to be used. This might mean writing your own spec screenplays - not with the goal of writing something "marketable", but with the goal of writing something that channels and fully realizes the power of your voice - the uniqueness of you. It might mean making your own films - short films, webseries, even features. This is investment. It takes time. Very likely it'll cost you money. But you must, must invest in your voice. If you do not create things that reflect your voice, no one will know what makes you worth hiring!

This investment serves an additional function: it helps you refine your craft. The more work you do, the better at it you become. So don't shy away from taking classes, joining workshops, or (if you're lucky) going back to school. But use those opportunities not just to refine your craft, but to refine the way you use your craft to project your voice.

AmplificationYour voice carries only as far as you push it. I've known some wonderful filmmakers over the years who've done great work but who only made halfhearted attempts to push it out to the world. An important component of investing in your voice is making sure it's amplified.

This really means two things:

It means putting your work out there. If you write screenplays, submit them to contests and share them with friends. Hire actors to do a table read and invite your industry contacts. Your voice is in those pages - amplify it! If you're a filmmaker, do whatever you can to get your work seen. Film festivals, private screenings, streaming platforms - whatever you need to do. Invest in this! Don't simply assume that 'if it's good, people will see it'.

It also means putting yourself out there. Your voice is your brand. Bring it into your social media - your tweets, Instagram posts, website, etc. Invest in your public image, even when you don't have much of a public.

It works!Having turned my attention to my own professional 'brand' only recently, I can say that the results are startlingly positive. Just this past year alone, I've been hired to write two feature screenplays (which had never happened to me before) and I've gotten interest and traction with multiple specs that had been out in circulation (in some cases) for several years. Almost immediately, when I began to invest in myself, and specifically in my 'voice', I saw a return on my investment.

I hope you're able to see the same results, too. It's a lot of work, and it can be a scary plunge (especially when you start actually spending money - that's terrifying!) but it's more than worth it.

What does "invest in your voice" mean to you? Have you tried it? Is it working? I'd love to read your success stories in the comments!

-Arnon

****************************************************************

ResourcesTo get you started, here are some resources I've found useful:

RAW MATERIALS: Carole Kirschner's fantastic (and free) e-book: "Telling your Story in 60 Seconds" - A simple and straightforward guide to digging into yourself and figuring out what you stand for. Going through the steps in this book has informed a lot of my writing in recent months, not to mention the website and social media overhaul.

CRAFT AND CREATION: Take advantage of the resources available online to learn more about the work you do. In addition to plying your craft and creating new content, check out the courses offered on Stage32.com or the great blog and video content on sites like studiobinder.com (to which I occasionally contribute).

AMPLIFICATION: It's not just about the usual social media sites. If you're a screenwriter, use platforms like coverfly.com to manage your contest submissions (Coverfly will actually reward you for high-performing screenplays by promoting them further to their industry network - they can amplify your voice!) Filmmakers can use services like filmhub.com to get their work (even short films!) out to more platforms. When you're ready to revamp your web presence and social media strategy, consider hiring a branding/marketing consultant (Kate den Rooijen was very helpful to me with this!)

And if you'd like to see the full Q&A, expertly moderated by Michelle Miller of "Mentors on the Mic", you can see it here!

February 19, 2021

A Screenwriter's Black List Strategy to Keep you Sane

The Black List website (www.blcklst.com) is a familiar destination for many screenwriters. It's a place where we can get (pay for) unbiased feedback on our screenplays.

I like the site. It's less expensive than other evaluation services, and it's well-known, so a flattering evaluation can have value when trying to sell a script or get a film off the ground. Perhaps its biggest weakness is that the evaluations are short, lacking some of the depth and detail that you might get from more expensive services. But in some ways, this can be helpful, too - not in the individual evaluation, but in the 'constellation' that forms when you get feedback from multiple readers. (More on this later!)

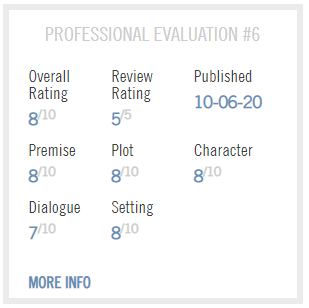

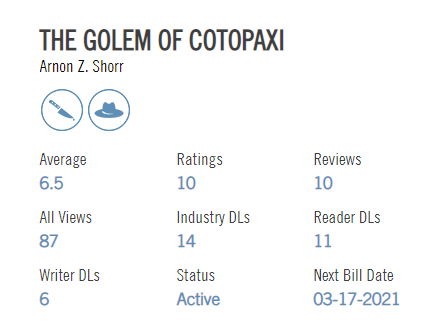

In addition to written feedback, your screenplay gets a series of scores - ratings on five aspects of your screenplay (Premise, Plot, Character, Dialogue and Setting), plus an overall rating (which is not an average, but a separate category that the reader assesses.)

When you get multiple evaluations, their scores are combined into an "Average" (I'm not sure how it's calculated) which becomes your screenplay's publicly-viewable "grade" on the site. All other evaluations are private, unless you permit the site to make them available.

It's very tempting to put a lot of stock in a script's Black List score. This isn't entirely misguided - high scores can have real-world consequences. Very high evaluation scores (8 or more) earn free months of hosting on the site and free additional evaluations. Screenplays with a high average score from multiple evaluations are included in the site's "Top Lists" - organized in weekly, monthly, quarterly (the most useful) and yearly categories. Producers regularly scout these lists for potential films to produce.

Between the written feedback, the scores, the dangling carrot of 'rewards' for high scores, the monthly 'hosting fee' and the evaluation costs, what's the best way to make the most of The Black List's features and services?

Initial Feedback - The First EvaluationsWhen you've written your screenplay and polished it to a point where it's ready for some unbiased feedback, it may be a good time to get a couple of initial evaluations. I like to do this before I subject myself to the expense of screenplay competitions - it's a way of 'testing the waters' with a script. If it scores well, screenplay contests might be worth the expense. If it scores poorly, I had better improve it before submitting it anywhere!

So I start with two evaluations on blcklst.com.

Why two? There are three reasons:

1) Screenplay evaluations are subjective! Two people reading the same script will often have very different experiences of it. You should never make significant changes to a script based on only one evaluation (unless you wholeheartedly agree with the evaluation). The more evaluations you get, the clearer the 'constellation' of feedback.

2) To get an evaluation, you also need to pay to 'host' your script on The Black List website. If you're paying for the month of hosting, you might as well get a bit more mileage out of it with an additional evaluation.

3) There are a few 'hidden perks' to getting multiple evaluations on The Black List. If both evaluations score well (averaging more than 6.15 or so - this figure changes) your script gets listed in the quarterly "Top List", where it's more likely to be spotted by industry readers on the lookout for new screenplays to acquire. Also, if your screenplay gets two evaluations with a very wide disparity between them (say, a 7 and a 4), the site provides you with a free additional evaluation - a sort of 'tie-breaker' to see which of the extreme scores was the 'fluke'). You can't get these 'hidden perks' with just one evaluation.

The Second Round - Improving the Score

The Second Round - Improving the ScoreIf you're getting high scores on the first round of evaluations, that tells you your script is likely to be well-received, and you can skip this step.

But more likely than not, you've got some work to do! Read the evaluations carefully, and see if there are common notes between them. This is especially important when there are big disparities in the scores.

I once submitted a script for two evaluations. The first scored an 8 overall (which triggers a 'hidden perk' - two free evaluations!) The second scored a 7... then, on the same draft, those free evaluations scored a 6 and a 5. What was I to do with that range of responses?

It turned out that all four evaluators identified the same problem in the screenplay. The first one thought it was a minor flaw in an otherwise spectacular piece. The last one thought it was crippling to the story and fatal to the screenplay. By looking at all the evaluations together, I was able to discover the common issue and address it on the next editing round.Once you've fixed up your script based on the feedback you've received, it's time to upload the new draft and get new scores.

BUT WAIT! Before you do anything, take a look at your current average. If it's 6 or more, you're in reasonably good shape, with a good chance of hitting that quarterly "top list" if you just get one or two more high-scoring evaluations. If it's below 6, consider starting fresh. The Black List allows you to wipe the slate clean for a new draft! This resets your score and clears all the old evaluations out of the way.When you're ready, and after you've decided whether to keep or get rid of your old evaluations, get yourself two more evaluations.

Rinse and RepeatKeep going like this. Get feedback, improve your script, get more feedback, improve, get feedback, improve, etc.

Your goal is twofold: use the service as an inexpensive way to get feedback that will make your screenplay better, and get on those top lists!

Once you're on the quarterly top list, you may still have tweaks to make to your screenplay, but it's in better shape than most of the spec scripts in circulation, so you can feel confident about sending it out.

Staying On TopEvery three months or so, your script will 'age out' of the quarterly Top List. If you haven't sold it yet, or if you'd like to boost its visibility, get two more evaluations.

Of course, there's no guarantee that these two evaluations will average above the Top List minimum (The Top List only counts your evaluations that occurred within its timeframe - so the quarterly list only looks at the average of evaluations from the last three months). Be prepared for that! But if your last round of evaluations was particularly strong, there's a good chance you'll hit the mark.

The Lucky StreakIf you score an 8 or higher, The Black List provides you with two free evaluations. If those score 8s, you get two more free evaluations from each of them. This can go on and on until you hit the site's limit (by which point you've likely got one of the highest average scores on the site).

This hasn't happened to me yet, but a screenwriter can dream, right?

When to StopAt a certain point, you've got to stop throwing money at your screenplay. When should you stop paying for Black List evaluations and hosting?

Of course, if your screenplay is doing well in the writing contests, drawing attention and getting buzz, you probably don't need The Black List anymore. Bravo!

But the harder plug to pull is on a screenplay that just can't seem to improve. No matter how many times you tweak or revise it, you can't seem to break past a 6. If you've gone a few rounds with evaluations and revisions, and you can't seem to break through, consider putting that screenplay aside. Not forever! Heaven forfend! Just long enough to write a few others, build more skills, tell other stories, and let the ideas percolate. If there's something about your screenplay that consistently fails to 'click' with readers, you're more likely to figure out what it is if you give yourself some distance and time away.

As of this writing, I've got one screenplay on The Black List, and may add another soon. If you'd like to see it (and you're a member of the site) check it out here:

As you can see, with 10 evaluations, I've had this thing on the site for a while (and got the benefit of two free evaluations from an '8' score, plus a couple of other freebies for contributing to The Black List blog.)

How do you use The Black List? Have you ever gotten a lucky streak? I'd love to hear from you!