Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 157

March 2, 2011

A Look at Lover's Eyes by Guest Blogger Jo Manning - Part Two

Copyright The Art of Mourning

Copyright The Art of MourningAlthough the craze for Lover's Eyes – and it was a craze, thanks to the Prince Regent, later King George IV, who was said to have exchanged lovers' eyes with his putative wife, Maria Fitzherbert and perhaps with his lover, Mary Robinson (the actress known as Perdita) – flourished for only a short time, his niece Queen Victoria years later was also said to be fond of them and gave them as gifts. To quote Candice Hern, a fellow writer of historical romance novels, "even though the notion of eye brooches was by that time very old-fashioned."

Ah, but in their day…! Christopher Stocks, writing in the Patek Philippe Magazine last year, noted:

"The combination of royalty and society was as potent then as it is today, and before long the fashion for eye miniatures spread through European high society and as far as Russia and the U.S."

I first became aware of eye miniatures when I sat in on a presentation given by Candice Hern, as a matter of fact. This was some years ago at a Romance Writers of America conference. Candice's very fine website shows the eyes in her collection:

Copyright Candice Hern

Copyright Candice HernThe examples displayed are prime, and are indeed lovely. Hers are all set into brooches; two show blue-eyed women; two are brown-eyed men. Who they are, again, is not known, and neither are the artists who painted them nor for whom they were intended, though we do have clues that several – and maybe a lot more than several – were painted by the prolific and noted miniaturists Richard Cosway and George Engleheart. (Ozias Humphry is said to have painted a few, also.)

Though a number of miniatures bearing the signature of Cosway are suspected not to be his, Engleheart did make a practice in his later years of initialing or signing his name to his work and these are considered genuine, not fakes. (These jottings are not easy to see unless the eye miniature is removed from its setting.)

Speaking of fakes, they are, alas, proliferating in this age of photo-shopping and cropping and Internet image borrowing. They can, however, be distinguished easily from the real thing upon close inspection owing to the presence of pixels rather than brushstrokes. See this very good article by the late Barry Weber, an expert in the field who often appeared on PBS's Antiques Road Show.

Weber went on to say that "murky colors that use dark sepia tones" should make one wary, as these colors may be "a heavy-handed effort to falsify age." He also cautioned, "an antique frame doesn't add authenticity to the painting." Camilla Lombardi, director of the portrait miniatures department at Bonham's in London has been seeing an increasing number of fakes as the real thing becomes rarer, particularly noting caution if a nose, or part of a nose, appears in an eye miniature. She says that in genuine eye miniatures there should be "no real sign of the nose where you would expect it, whereas in a cut-down eye miniature you would see the line of the nose and shadow where the corner of the eye meets the bridge of the nose."

Copyright PBS

Copyright PBSWhat George Williamson had to say in The Art of the Miniature Painter about the care of miniature portraits would apply as well to the much tinier lover's eyes:

"Miniatures should not be exposed to a strong light… Violent changes of temperature are to be avoided, and should the ivory become too dry it may crack… Lockets and pendants containing miniatures should not be worn at dances, or on any occasion where the wearer is liable to become overheated, as acid condensation takes place inside the glass which may ruin the painting."

Ather problem – which perhaps accounts for the rarity of eye miniatures set into rings rather than brooches, pendants, or cases – is that water could get under the glass protecting the miniature and wash away the watercolors. Washing hands was death to a lover's eye set into a ring.

Copyright parisatelier.blogspot.com

Copyright parisatelier.blogspot.comAnd what are these eye miniatures, these oh-so-romantic lover's eyes, worth in today's antique jewelry market? Barry Weber noted, "Few pieces cost less than $1,000." He added, "American pieces are spectacularly rare," mentioning "one jewel-encrusted example worth $20,000." Christopher Stocks values unattributed pieces at $1,500, whilst attributed pieces could go as high as $7,500 each. In the 1950s, when no one wanted them, they could be gotten for next to nothing, out of favor and even considered "repulsive" – to quote the art critic David Piper in 1957 -- as both jewelry and art.

The oft-cited reference – in Charles Dickens' 1848 novel, Dombey and Son – reinforces Piper's condemnation, with the dismissive description of the lover's eye worn by the elderly spinster Miss Tox as "representing a fishy old eye…" How anyone could see these eyes in that way is just another example of how one person's treasure can be considered another person's trash, or, de gustibus non disputandum est.

Lover's eyes are exquisite, in the opinion of many contemporary collectors, connoisseurs, and lovers of beautiful objects, and this exhibition will bring them to the forefront once again. It has only taken some 200 years! And, reader, do go through Great-Grandmother's box of trinkets in the attic once more, for who knows what precious eyes may be lurking there, desperate for the light.

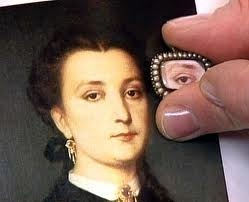

A 20th-century version of an eye miniature, from a Bronzino portrait; note the differences between this and a classic lover's eye.

Published on March 02, 2011 01:06

March 1, 2011

A Look at Lover's Eyes by Guest Blogger Jo Manning - Part One

Copyright - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Copyright - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

In February of 2012, "The Look Of Love," an exhibition dedicated to the art of Georgian-era eye miniatures, will take place at Alabama's Birmingham Museum of Art, curated by Graham C. Boettcher. It will feature the collection of Birmingham residents Nan and David Skier; theirs is perhaps one of the largest collections of this art-cum-jewelry in the world, at some 70 pieces.

I am one of the contributors to the exhibition catalog, though I own but one lover's eye. Mine is a man's eye surrounded by seed pearls and set in a gold ring. This ring is shown on page 165 of my biography of Grace Dalrymple Elliott, My Lady Scandalous (Simon and Schuster, 2005). I do not know who the man was, nor do I know the name of the artist. I also do not know for whom it was intended, but I believe it was a mourning ring.

Copyright - The great majority of eye miniatures fall into this category of nameless subject/nameless artist/unknown owner. Moreover, not much has been written on this hybrid form of painting/jewelry, nor are there significant sources for research into this topic to fill in the gaps. What has been written tends to repeat the same historical anecdotes but does not provide much in the way of new material. This 2012 exhibit promises to change this situation. The three essays I have read recently quote exactly the same material; it is way past time to break new ground!

Copyright - The great majority of eye miniatures fall into this category of nameless subject/nameless artist/unknown owner. Moreover, not much has been written on this hybrid form of painting/jewelry, nor are there significant sources for research into this topic to fill in the gaps. What has been written tends to repeat the same historical anecdotes but does not provide much in the way of new material. This 2012 exhibit promises to change this situation. The three essays I have read recently quote exactly the same material; it is way past time to break new ground!

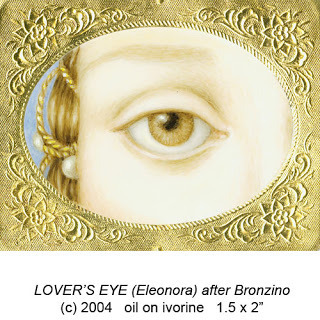

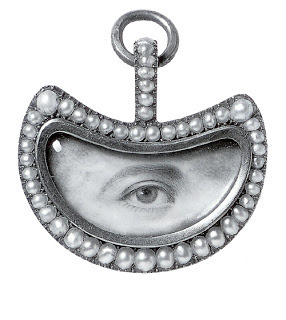

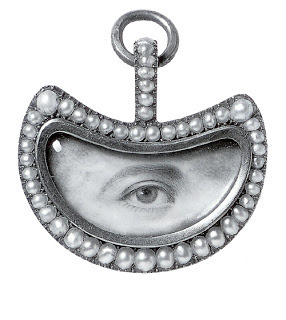

Portrait miniatures abounded in the time of the English Georges in the 18th century/early 19th century, eye miniatures did not. These miniscule paintings very carefully delineated one eye, one eyebrow, perhaps a some wispy strands of hair falling to one side [one of the ways to differentiate between men and women), but never a nose. It was, to put it romantically, an eye – usually the eye of a lover –floating untethered in space, gazing unabashedly at the beloved.

These miniatures were not meant to be seen by just anyone. Their nature was secret, more clandestine, as it were, not at all public. They were meant to be love tokens exchanged by a pair of lovers...and theirs alone. The owner of the eye miniature could carry it safely, knowing that only those with whom she/he chose to share her/his innermost secrets would know whose eye it was.

Those that were not tokens of a lover's affection – and there are a fair number of these -- fall into the category of sentimental or mourning jewelry and are identified by a single diamond tear falling from the eye, or a surround of seed pearls, pearls being another metaphor for tears or mourning. (Sometimes a tiny lock of hair was placed behind the painting, reminding one of those strange pieces of hair jewelry favored by the Victorians.)

Copyright The Art of Mourning

Copyright The Art of Mourning

The eye miniatures were usually painted in watercolor on ivory, vellum, or even waxed playing card, and protected by a glass cover. Average size was barely half an inch across. The eyes not surrounded by pearls were often framed in garnets, amethysts, and other popular gemstones of the period. It has been estimated that only one to two thousand of these pieces were ever made, making them very rare and thus very collectible.

Copyright The V and A Museum

Copyright The V and A Museum

The tear(s) are easier to see here, and, of course, the seed pearls emphasize this is a bereavement brooch.

Part Two Coming Soon!

Copyright - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Copyright - The Philadelphia Museum of Art In February of 2012, "The Look Of Love," an exhibition dedicated to the art of Georgian-era eye miniatures, will take place at Alabama's Birmingham Museum of Art, curated by Graham C. Boettcher. It will feature the collection of Birmingham residents Nan and David Skier; theirs is perhaps one of the largest collections of this art-cum-jewelry in the world, at some 70 pieces.

I am one of the contributors to the exhibition catalog, though I own but one lover's eye. Mine is a man's eye surrounded by seed pearls and set in a gold ring. This ring is shown on page 165 of my biography of Grace Dalrymple Elliott, My Lady Scandalous (Simon and Schuster, 2005). I do not know who the man was, nor do I know the name of the artist. I also do not know for whom it was intended, but I believe it was a mourning ring.

Copyright - The great majority of eye miniatures fall into this category of nameless subject/nameless artist/unknown owner. Moreover, not much has been written on this hybrid form of painting/jewelry, nor are there significant sources for research into this topic to fill in the gaps. What has been written tends to repeat the same historical anecdotes but does not provide much in the way of new material. This 2012 exhibit promises to change this situation. The three essays I have read recently quote exactly the same material; it is way past time to break new ground!

Copyright - The great majority of eye miniatures fall into this category of nameless subject/nameless artist/unknown owner. Moreover, not much has been written on this hybrid form of painting/jewelry, nor are there significant sources for research into this topic to fill in the gaps. What has been written tends to repeat the same historical anecdotes but does not provide much in the way of new material. This 2012 exhibit promises to change this situation. The three essays I have read recently quote exactly the same material; it is way past time to break new ground!

Portrait miniatures abounded in the time of the English Georges in the 18th century/early 19th century, eye miniatures did not. These miniscule paintings very carefully delineated one eye, one eyebrow, perhaps a some wispy strands of hair falling to one side [one of the ways to differentiate between men and women), but never a nose. It was, to put it romantically, an eye – usually the eye of a lover –floating untethered in space, gazing unabashedly at the beloved.

These miniatures were not meant to be seen by just anyone. Their nature was secret, more clandestine, as it were, not at all public. They were meant to be love tokens exchanged by a pair of lovers...and theirs alone. The owner of the eye miniature could carry it safely, knowing that only those with whom she/he chose to share her/his innermost secrets would know whose eye it was.

Those that were not tokens of a lover's affection – and there are a fair number of these -- fall into the category of sentimental or mourning jewelry and are identified by a single diamond tear falling from the eye, or a surround of seed pearls, pearls being another metaphor for tears or mourning. (Sometimes a tiny lock of hair was placed behind the painting, reminding one of those strange pieces of hair jewelry favored by the Victorians.)

Copyright The Art of Mourning

Copyright The Art of MourningThe eye miniatures were usually painted in watercolor on ivory, vellum, or even waxed playing card, and protected by a glass cover. Average size was barely half an inch across. The eyes not surrounded by pearls were often framed in garnets, amethysts, and other popular gemstones of the period. It has been estimated that only one to two thousand of these pieces were ever made, making them very rare and thus very collectible.

Copyright The V and A Museum

Copyright The V and A MuseumThe tear(s) are easier to see here, and, of course, the seed pearls emphasize this is a bereavement brooch.

Part Two Coming Soon!

Published on March 01, 2011 01:00

February 28, 2011

Nunhead Cemetery

Nunhead Cemetery in Southwark is perhaps the least known, but the most attractive, of the seven Victorian cemeteries on the outskirts of London. It's formal avenues of towering lime trees and original Victorian planting gives it a truly Gothic feel. Its history, architecture and stunning views make it a fascinating and beautiful place to visit. While much of the cemetery is mysterious and overgrown, many of its features have recently been restored to their former glory. This is thanks to funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and Southwark Council.

There is a tour conducted by the Friends of the cemetery, open to all, on the last Sunday of each month, starting from the Linden Grove gates at 2:15 p.m. and the two-hour guided tour of a romantic and overgrown Victorian cemetery features 1,000 ivy-clad angels and mighty Victorians buried in the green heart of Peckham. Consecrated in 1840, Nunhead contains examples of the magnificent monuments erected in memory of the most eminent citizens of the day, which contrast sharply with the small, simple headstones marking common, or public, burials. It's formal avenue of towering limes and the Gothic gloom of the original Victorian planting gives way to paths which recall the country lanes of a bygone era.

The following account of Nunhead Cemetery appeared in a volume titled, Old Humphrey's Walks in London and its Neighbourhood (1845) -

This Nunhead Cemetery of All Saints, occupies a commanding site between Peckham and the Kent road, sloping down to the east, north, and south-west, at a distance of some three or four miles from London, and, though far from being completed, gives a fair promise of equaling those which have already won the public approbation. It is the largest of all the cemeteries, comprising at least fifty acres.

In walking to this place I observed, on a neighbouring hill, a singular-looking erection, and the gravedigger, who is even now, with an assistant, preparing a "narrow house" for an inanimate tenant, tells me it is a telegraph. . . . There is a glorious view of London from this spot. The five oaks stretching themselves across the cemetery are strikingly attractive; and when the church is erected on the brow of the hill yonder, it will be a goodly spectacle. The palisades of the boundary, mounting tier above tier; the fine swell of the ground and commanding slope; the groups of young trees, and flowers of all hues, are very imposing. In a few fleeting years the cemetery will be, indeed, an interesting spectacle.

I have walked round the spacious enclosure. What an extended space for a grave-ground ! What a goodly homestead for the king of terrors! Here seems to be room enough to bury us all! At present the monuments are but few; but this is a want that mortality will soon supply. Fever, and consumption, and death, and time, are industriously at work. It is not to one, but to all, that the voice of the Eternal has gone forth: " Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return," Gen iii. 19.

And in The Sunday At Home, Voume 25 (1878), we read:

MANY "parks" in the suburbs of London are now treeless, or planted only, in front "gardens," with shrub-like trees. A visitor of Nnnhead Cemetery, however, unacquainted with its history, must feel inclined to say, "Here is a picturesquely wooded and undulating Surrey park, in which double rows of houses have not supplanted shady avenues; the turf and trees, over and under which a favoured few once wandered, have been turned into a receptacle and a canopy for thousands of the dead, who, whatever was their station in life, are like the dead slave in the Greek Anthology, all now "equal to Darius.'"

Nevertheless, some forty years ago, the cemetery was simply fifty acres of field and meadow. All the tasteful planting has been done by the cemetery company, and it is rare as well as rich, including shrubs which prove that landscape-gardening here is made a speciality, and that no expense is spared upon it. Within the cemetery, there is an ably superintended, strongly-manned nursery, which keeps the flower-beds bright, and the graves also, after the old Welsh custom. It is curious to think of little coffin-shaped parterres, bordered with whitewashed stones, and planted with old-fashioned flowers, far away in the quiet hollows of the Welsh hills—most of the graves with no other memorial than the piously-tended flowers, when on a summer day we see the blaze of blossom at the foot of gleaming marble and glittering granite in Nunhead. But it is winter at the time of our pleasant wanderings there. Some of the graves are still bright with flowers, but glossy shrubs are their chief adornment. Throughout the place, however, laurustinus blossoms freely, although chrysanthemums hang wilted heads, and rowan trees and holly and rose bushes are red with equally seasonable berries. In spite of gardener's care, and the mildness of the season, there is nevertheless, an unmistakable look of winter in the place. Trees and bushes are leafless; dark, dank dead leaves lie trodden, or waiting to be trodden, into the fat clay; jungles of leafless sprays bend under sugared-almond-like ovals.

Although, since the Bishop of Winchester consecrated the forty-acre All Saints portion of the ground in 1840, some 45,000 persons have been buried in that portion, and the unconsecrated divided from it by no invidious boundary,—there are solitudes still in Nunhead cemetery; graveless, or only dotted with single tombstones, white, grey, black or green. Moss-grown red paths wind into nooks that seem, so far as either dead or living are concerned, as far from London as if thoy were in the Fiji Islands, until we hear the rumble and panting of one of the trains that frequently rush around. The roar of London is audible in Nunhead; the drab masonry of South London, redeemed from meanness only by its smokily, mistily, mysterious mass, spreads almost to the gates, but on other sides you see green swelling country, houseless, or only marred by straggling lines of brick and mortar.

The first grave in Nunhead was dug in October 1840. The average number of burials in it, during the last ten years, has been 1685 per annum, 1350 in the consecrated, and 335 in the unconsecrated ground. The total of burials having been more than four myriads, it is almost startling to hear the number of the "square" in which any one of the slightest notability or notoriety lies, given without a second's hesitation by the superintendent. Before singling out graves of any kind of note, let us ramble round the cemetery.

The birds are not singing, but their half sad little chirpings and twitterings seem more in harmony with a burial ground than full sung, especially on a day like this, when a winter sun is vainly trying to shine through brown-holland-like clouds. The sheen of the silver birches' bark seems self-evolved in the sombre midday dusk; willows and ashes "weep" still over green stones, on whose graves they have already shed their leaves.

Nunhead Cemetery is open daily, 8am-4pm in winter.

You can read a poem entitled Nunhead Cemetery by Charlotte Mew here and watch a video of the cemetery here.

Published on February 28, 2011 01:11

February 27, 2011

And the Winner is....Pride and Prejudice!

Colin Firth is a favorite for the best actor Oscar to match his Golden Globe and BAFTA awards -- for his role in The King's Speech. But apparently he has already won our hearts, in 1995, in the BBC's miniseries of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. Who can forget his memorable Fitzwilliam Darcy?

Colin Firth is a favorite for the best actor Oscar to match his Golden Globe and BAFTA awards -- for his role in The King's Speech. But apparently he has already won our hearts, in 1995, in the BBC's miniseries of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. Who can forget his memorable Fitzwilliam Darcy?Victoria here; the January issue of the BBC History Magazine caught up with me and I was amused to see their list of favorite "Best Television Costume Dramas." None of us will be surprised, I am sure, to find this 1995 production in first place. The magazine reports that 14.1% of their 3,229 respondents voted for P and P.

The conclusion of Pride and Prejudice, the miniseries

The conclusion of Pride and Prejudice, the miniseriesWatch the "Colin in lake with wet shirt" video here (1,605,694 views so far).

In second place, and this was a bit of a surprise to me, was I, Claudius from 1976. How young Derek Jacobi looks in this DVD cover picture of him in the title role.

I remember this wonderful series about the supposedly mad Claudius and the wild history of the Rome of which he eventually became the Emperor. I particularly remember the role of Livia, wife Augustus, played by Sian Phillips. She was the personification of malevolence. The series was based on the novel by Robert Graves and ran for several seasons. It might have been high in the memory of viewers because the BBC has recently done a radio drama of the novel.

Upstairs, Downstairs, which began in 1971, took third place. Again, it is familiar to viewers because it has recently returned in a new version, yet to be seen on this side of the pond. The adventures of the Bellamy family and their servants was required watching for me for many years, and I have enjoyed the dvds too. Kristine saw a couple of the new episodes when she was in London at New Year's and says we will all love them when they arrive here.

Upstairs, Downstairs, which began in 1971, took third place. Again, it is familiar to viewers because it has recently returned in a new version, yet to be seen on this side of the pond. The adventures of the Bellamy family and their servants was required watching for me for many years, and I have enjoyed the dvds too. Kristine saw a couple of the new episodes when she was in London at New Year's and says we will all love them when they arrive here.

In fourth place was Downton Abbey, which was a distinct disappointment to me. It sounded like it had everything I would adore -- script by Julian Fellowes, actors such as Hugh Bonneville and Maggie Smith, a huge pile of a country house that made Wretched Excess look tasteful...what could possibly be unsatisfactory? Cliche-ridden story, unconvincing characters, silly disagreements masquerading as substantial -- I can only think that people voted for it because they remembered it so well, not because it was GOOD. I just felt I'd seen it all before, and Fellowes packed so many "tried-and-true" situations into it that I wanted to scream. Of course, I have to say it is much better than almost anything else on tv. Damned with faint praise??? I do look forward to improvements next season. Never say die.

In fourth place was Downton Abbey, which was a distinct disappointment to me. It sounded like it had everything I would adore -- script by Julian Fellowes, actors such as Hugh Bonneville and Maggie Smith, a huge pile of a country house that made Wretched Excess look tasteful...what could possibly be unsatisfactory? Cliche-ridden story, unconvincing characters, silly disagreements masquerading as substantial -- I can only think that people voted for it because they remembered it so well, not because it was GOOD. I just felt I'd seen it all before, and Fellowes packed so many "tried-and-true" situations into it that I wanted to scream. Of course, I have to say it is much better than almost anything else on tv. Damned with faint praise??? I do look forward to improvements next season. Never say die. Cranford, from 2007, won fifth place. And this one I really enjoyed. Taken from several novels by Elisabeth Gaskell, the story revolves around life in an 1840's English Village. The coming of the railroad challenges a number of traditions but life -- birth, courtship, marriage, and death -- continues to absorb the villagers. Of course, anything with Judi Dench will by on my 'must" list -- but I used to feel that way about Maggie Smith too.

Cranford, from 2007, won fifth place. And this one I really enjoyed. Taken from several novels by Elisabeth Gaskell, the story revolves around life in an 1840's English Village. The coming of the railroad challenges a number of traditions but life -- birth, courtship, marriage, and death -- continues to absorb the villagers. Of course, anything with Judi Dench will by on my 'must" list -- but I used to feel that way about Maggie Smith too. The BBC History Magazine (in an article by David Musgrove) expressed some surprise that The Tudors only ended up in 14th place. Given the current fascination with all things Tudor and Elizabethan, perhaps that was unexpected by many. But, though I enjoyed every episode and never had the irritation I felt at Downton Abby's trite story, I really didn't think The Tudors was all that great. Costumes were wonderful; and the cast was good. But how many of us could really see Jonathan Rhys-Meyers as Henry VIII. Even when they padded him up at the end, he looked like a hunky stud with pillows tied around his waist. Give me Charles Laughton as Henry any time!

The BBC History Magazine (in an article by David Musgrove) expressed some surprise that The Tudors only ended up in 14th place. Given the current fascination with all things Tudor and Elizabethan, perhaps that was unexpected by many. But, though I enjoyed every episode and never had the irritation I felt at Downton Abby's trite story, I really didn't think The Tudors was all that great. Costumes were wonderful; and the cast was good. But how many of us could really see Jonathan Rhys-Meyers as Henry VIII. Even when they padded him up at the end, he looked like a hunky stud with pillows tied around his waist. Give me Charles Laughton as Henry any time! Sixth place went to another of my favorites, Brideshead Revisited (1981) and seventh went to The Forsyte Saga from 1967, which I watch every 3 or 4 years,whether I need to or not!.

Sixth place went to another of my favorites, Brideshead Revisited (1981) and seventh went to The Forsyte Saga from 1967, which I watch every 3 or 4 years,whether I need to or not!.To see the complete list of also-rans, click here.

Soames, Irene and Young Jolyon

Soames, Irene and Young JolyonThe Forsyte Saga

Published on February 27, 2011 02:10

February 25, 2011

Sherlock Holmes Returns - Thrice

(1) Robert Downey Jr. will once again play the British detective in Sherlock Holmes 2, (2) a new, authorized Sherlock Holmes mystery novel will hit the stands in September of this year (3) Benjamin Cumberbatch returns as Masterpiece Mystery's 21st century incarnation of the detective.

Sherlock Holmes II (the film) is set in the year 1891, a year after the events in the first film, and will have Holmes chasing Moriarity and Dr. Watson pursuing his love life whilst assisting the detective. Downey says: "Unlike last time, where Holmes kept getting Watson into trouble, this time Watson is getting Holmes out of trouble, and they're both in deeper trouble than I think the audience could have imagined we could go.... All manner of nastiness has just occurred."

This time out, the duo are joined by the feisty Sim, played by actress Noomi Rapace. Also making an appearance is Sherlock's brother Mycroft Holmes, played by actor Stephen Fry, a character who producer Susan Downey (Robert's wife) describes as "stranger and perhaps even more brilliant" than the English detective. Fry recently said, "I play Mycroft, Sherlock Holmes' brother - the smarter brother, I hasten to add. He's so lazy that he never gets the reputation that Sherlock does. Historically it's a very interesting character, and as a lover of Sherlock Holmes since I was a boy I've always enjoyed that character myself. I hope that people enjoy it. It's certainly been fun making the picture." And how does Fry feel about a Yank playing the iconically British Holmes? "To some extent, but he's such a charismatic and likeable screen presence, Robert, that you very soon forget it. More than most, he owns every second of screen time. He's just wonderfully likeable. He's the real thing."

The film opens in October in the UK and in December in the US.

Meanwhile, author and screenwriter Anthony Horowitz has been tapped by the Arthur Conan Doyle Estate to write a brand new Sherlock Holmes mystery novel. Horowitz said he's writing "a first-rate mystery for a modern audience while remaining absolutely true to the spirit of the original." Orion publisher Jon Wood promised the author's "passion for Holmes and his consummate narrative trickery will ensure that this new story will not only blow away Conan Doyle aficionados but also bring the sleuth to a whole new audience."

This is the first time that the Estate has tapped anyone to continue the Holmes tradition and it's no wonder they chose Horowitz, who has proven his story telling abilities by creating Foyle's War and contributing to several other crime drama series, including Midsomer Murders and adaptations of Agatha Christie's Poirot novels.

And finally, we can all look forward to Benedict Cumberbatch's return as Holmes in three new Masterpiece Mystery episodes this Autumn. The game is certainly afoot.

Published on February 25, 2011 01:38

February 24, 2011

Sir Thomas Lawrence Arrives at Yale

Opening today, February 24, 2011: Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power and Brilliance will be on view at the Yale Center for British Art until June 5, 2011.

Kristine and Jo Manning both saw the exhibition in its first venue at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Victoria hopes to be there in a few days...and I will report on my visit. You can read our previous posts on this blog on 10/20/10, 1/7-8-9-10/11, and 2/2/11. We find Sir Thomas to be a fascinating subject and the exhibition equally so.

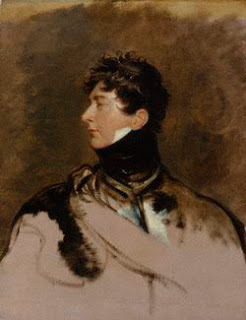

Thomas Lawrence, self-portrait from 1788, right, was born in Bristol in 1769. He was a child prodigy and by age 10, when his family moved to Bath, he supported then with his drawings in pastels. He moved to London at age 18 and was soon hailed as an up and coming talented successor to Sir Joshua Reynolds, then Britain's leading portraitist.

Thomas Lawrence, self-portrait from 1788, right, was born in Bristol in 1769. He was a child prodigy and by age 10, when his family moved to Bath, he supported then with his drawings in pastels. He moved to London at age 18 and was soon hailed as an up and coming talented successor to Sir Joshua Reynolds, then Britain's leading portraitist.

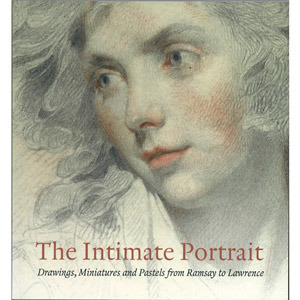

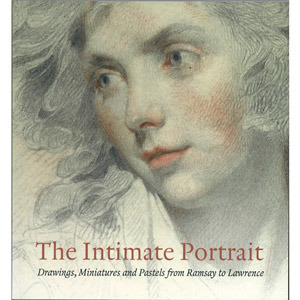

One of his fine portraits, of a friend's wife, Mary Hamilton, is shown in the exhibition, and makes one eager for more of the early pastels. But clients were eager for portraits in oils, and Lawrence excelled here too. He drew Mary Hamilton in pencil, red and black chalk in 1789. The British Museum, which owns the work, writes, "This important drawing of Mary Hamilton is arguably the most beautiful female portrait of its type remaining in this country." A detail of the drawing was used as the cover for a 2008 exhibition at the British Museum The Intimate Portrait, below.

Lawrence's portrait of Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, brought him fame and eventually fortune. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1790, the canvas was praised for its detail and its fine brushwork.

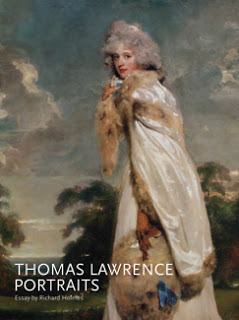

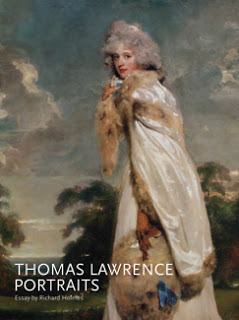

The stunning portrait of actress Elizabeth Farren, later Countess of Derby, exhibited at the RA in 1790, is one of the exhibition posters offered for purchase. For information on the Yale exhibition, the catalogue, posters and more, click here. Elizabeth Farren (1759-1829) began her London stage career in 1777, appearing in Goldsmith's She Stoops to Conquer. She became the object of Lord Derby's affections, and after his first wife died, Farren married him in 1797. She thus retired from the theatre and became a countess, wife of a prominent Whig member of the House of Lords. They were parents of three children.

The stunning portrait of actress Elizabeth Farren, later Countess of Derby, exhibited at the RA in 1790, is one of the exhibition posters offered for purchase. For information on the Yale exhibition, the catalogue, posters and more, click here. Elizabeth Farren (1759-1829) began her London stage career in 1777, appearing in Goldsmith's She Stoops to Conquer. She became the object of Lord Derby's affections, and after his first wife died, Farren married him in 1797. She thus retired from the theatre and became a countess, wife of a prominent Whig member of the House of Lords. They were parents of three children. Jonathan Jones, reviewing the exhibition as shown in London, wrote in The Guardian: "Lawrence is a painter who triumphed in his lifetime, yet was forgotten afterwards. Why was he neglected? The question echoes through this extremely interesting exhibition... It is because he associated with the wrong royal... Raddled and bloated and unpopular, George IV looks out of Lawrence's Wallace Collection masterpiece as if he knows full well that in centuries to come, people will joke that 'there are pieces of lemon peel floating in the Thames that would make a better monarch'."

Jonathan Jones, reviewing the exhibition as shown in London, wrote in The Guardian: "Lawrence is a painter who triumphed in his lifetime, yet was forgotten afterwards. Why was he neglected? The question echoes through this extremely interesting exhibition... It is because he associated with the wrong royal... Raddled and bloated and unpopular, George IV looks out of Lawrence's Wallace Collection masterpiece as if he knows full well that in centuries to come, people will joke that 'there are pieces of lemon peel floating in the Thames that would make a better monarch'."But Lawrence's relationship with the Prince Regent, later George IV, was lucrative and certainly added to his fame. The Regent sent Lawrence around Europe to paint the leaders of the allied victory over Napoleon. The paintings hang in Windsor Castle, though many copies executed in Lawrence's studio, can be seen in palaces, mansions and museums worldwide.

The Duke of Wellington was the real hero of the battle, but many, including a coalition of European leaders contributed to the long-sought defeat of Napoleon. Lawrence painted the Duke a number of times, including here on the back of Copenhagen, the horse who carried him throughout the day-long Battle of Waterloo.

The Duke of Wellington was the real hero of the battle, but many, including a coalition of European leaders contributed to the long-sought defeat of Napoleon. Lawrence painted the Duke a number of times, including here on the back of Copenhagen, the horse who carried him throughout the day-long Battle of Waterloo.  Victoria has long adored this painting, from the collection of the Chicago Art Institute. As a child, she often stood in front of Mrs.Jens Wolff and wondered what made this elegant lady so sad. The portrait was commissioned in 1802 or 03 by the sister of Mrs. Wolff and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1815. Isabella Wolff was the wife of the Danish Consul in London; they divorced in 1813. She is portrayed as theErythraean Sibyl (similar to the Sistine Chapel version) and she gazes at a book of engravings by Michelangelo. Lawrence and Isabella Wolff may have been romantically involved for some years, though why it took the artist a dozen years to complete the portrait is a good question. They continued to write to one another until her death.

Victoria has long adored this painting, from the collection of the Chicago Art Institute. As a child, she often stood in front of Mrs.Jens Wolff and wondered what made this elegant lady so sad. The portrait was commissioned in 1802 or 03 by the sister of Mrs. Wolff and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1815. Isabella Wolff was the wife of the Danish Consul in London; they divorced in 1813. She is portrayed as theErythraean Sibyl (similar to the Sistine Chapel version) and she gazes at a book of engravings by Michelangelo. Lawrence and Isabella Wolff may have been romantically involved for some years, though why it took the artist a dozen years to complete the portrait is a good question. They continued to write to one another until her death.

Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power and Brilliance will be on display at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, until June 5, 2011. We will report again after our visit. For more information on the Yale Center for British Art, click here.

Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power and Brilliance will be on display at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, until June 5, 2011. We will report again after our visit. For more information on the Yale Center for British Art, click here.

Published on February 24, 2011 04:19

Sir Thomas Lawrence arrives at Yale

Opening today, February 24, 2011: Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power and Brilliance will be on view at the Yale Center for British Art until June 5, 2011.

Kristine and Jo Manning both saw the exhibition in its first venue at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Victoria hopes to be there in a few days...and I will report on my visit. You can read our previous posts on this blog on 10/20/10, 1/7-8-9-10/11, and 2/2/11. We find Sir Thomas to be a fascinating subject and the exhibition equally so.

Thomas Lawrence, self-portrait from 1788, right, was born in Bristol in 1769. He was a child prodigy and by age 10, when his family moved to Bath, he supported then with his drawings in pastels. He moved to London at age 18 and was soon hailed as an up and coming talented successor to Sir Joshua Reynolds, then Britain's leading portraitist.

Thomas Lawrence, self-portrait from 1788, right, was born in Bristol in 1769. He was a child prodigy and by age 10, when his family moved to Bath, he supported then with his drawings in pastels. He moved to London at age 18 and was soon hailed as an up and coming talented successor to Sir Joshua Reynolds, then Britain's leading portraitist.

One of his fine portraits, of a friend's wife, Mary Hamilton, is shown in the exhibition, and makes one eager for more of the early pastels. But clients were eager for portraits in oils, and Lawrence excelled here too. He drew Mary Hamilton in pencil, red and black chalk in 1789. The British Museum, which owns the work, writes, "This important drawing of Mary Hamilton is arguably the most beautiful female portrait of its type remaining in this country." A detail of the drawing was used as the cover for a 2008 exhibition at the British Museum The Intimate Portrait, below.

Lawrence's portrait of Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, brought him fame and eventually fortune. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1790, the canvas was praised for its detail and its fine brushwork.

The stunning portrait of actress Elizabeth Farren, later Countess of Derby, exhibited at the RA in 1790, is one of the exhibition posters offered for purchase. For information on the Yale exhibition, the catalogue, posters and more, click here. Elizabeth Farren (1759-1829) began her London stage career in 1777, appearing in Goldsmith's She Stoops to Conquer. She became the object of Lord Derby's affections, and after his first wife died, Farren married him in 1797. She thus retired from the theatre and became a countess, wife of a prominent Whig member of the House of Lords. They were parents of three children.

The stunning portrait of actress Elizabeth Farren, later Countess of Derby, exhibited at the RA in 1790, is one of the exhibition posters offered for purchase. For information on the Yale exhibition, the catalogue, posters and more, click here. Elizabeth Farren (1759-1829) began her London stage career in 1777, appearing in Goldsmith's She Stoops to Conquer. She became the object of Lord Derby's affections, and after his first wife died, Farren married him in 1797. She thus retired from the theatre and became a countess, wife of a prominent Whig member of the House of Lords. They were parents of three children. Jonathan Jones, reviewing the exhibition as shown in London, wrote in The Guardian: "Lawrence is a painter who triumphed in his lifetime, yet was forgotten afterwards. Why was he neglected? The question echoes through this extremely interesting exhibition... It is because he associated with the wrong royal... Raddled and bloated and unpopular, George IV looks out of Lawrence's Wallace Collection masterpiece as if he knows full well that in centuries to come, people will joke that 'there are pieces of lemon peel floating in the Thames that would make a better monarch'."

Jonathan Jones, reviewing the exhibition as shown in London, wrote in The Guardian: "Lawrence is a painter who triumphed in his lifetime, yet was forgotten afterwards. Why was he neglected? The question echoes through this extremely interesting exhibition... It is because he associated with the wrong royal... Raddled and bloated and unpopular, George IV looks out of Lawrence's Wallace Collection masterpiece as if he knows full well that in centuries to come, people will joke that 'there are pieces of lemon peel floating in the Thames that would make a better monarch'."But Lawrence's relationship with the Prince Regent, later George IV, was lucrative and certainly added to his fame. The Regent sent Lawrence around Europe to paint the leaders of the allied victory over Napoleon. The paintings hang in Windsor Castle, though many copies executed in Lawrence's studio, can be seen in palaces, mansions and museums worldwide.

The Duke of Wellington was the real hero of the battle, but many, including a coalition of European leaders contributed to the long-sought defeat of Napoleon. Lawrence painted the Duke a number of times, including here on the back of Copenhagen, the horse who carried him throughout the day-long Battle of Waterloo.

The Duke of Wellington was the real hero of the battle, but many, including a coalition of European leaders contributed to the long-sought defeat of Napoleon. Lawrence painted the Duke a number of times, including here on the back of Copenhagen, the horse who carried him throughout the day-long Battle of Waterloo.  Victoria has long adored this painting, from the collection of the Chicago Art Institute. As a child, she often stood in front of Mrs.Jens Wolff and wondered what made this elegant lady so sad. The portrait was commissioned in 1802 or 03 by the sister of Mrs. Wolff and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1815. Isabella Wolff was the wife of the Danish Consul in London; they divorced in 1813. She is portrayed as theErythraean Sibyl (similar to the Sistine Chapel version) and she gazes at a book of engravings by Michelangelo. Lawrence and Isabella Wolff may have been romantically involved for some years, though why it took the artist a dozen years to complete the portrait is a good question. They continued to write to one another until her death.

Victoria has long adored this painting, from the collection of the Chicago Art Institute. As a child, she often stood in front of Mrs.Jens Wolff and wondered what made this elegant lady so sad. The portrait was commissioned in 1802 or 03 by the sister of Mrs. Wolff and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1815. Isabella Wolff was the wife of the Danish Consul in London; they divorced in 1813. She is portrayed as theErythraean Sibyl (similar to the Sistine Chapel version) and she gazes at a book of engravings by Michelangelo. Lawrence and Isabella Wolff may have been romantically involved for some years, though why it took the artist a dozen years to complete the portrait is a good question. They continued to write to one another until her death.

Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power and Brilliance will be on display at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, until June 5, 2011. We will report again after our visit. For more information on the Yale Center for British Art, click here.

Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power and Brilliance will be on display at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, until June 5, 2011. We will report again after our visit. For more information on the Yale Center for British Art, click here.

Published on February 24, 2011 04:19

February 23, 2011

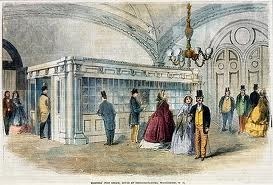

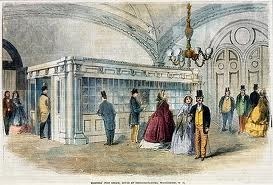

The London Post Office 1850 - Part Three

In this series, we turn to the words of Mr. Charles Dickens which appeared in the March 30, 1850 edition of the publication he edited, Household Words. The following article is chock full of details about how the Post Office operated in Victorian London and also about the mail and other items it processed on a daily basis.

The piece follows the progress of two gentlemen who make a visit to the Post Office and Part Three continues -

The friends were informed that 70,000,000 newspapers pass through all the post-offices every year. Upwards of 80,000,000 newspaper stamps are distributed annually from the Stamp office; but, most of the London papers are conveyed into the country by early trains. On the other hand, frequently the same paper passes through the post several times, which accounts for the small excess of 10,000,000 stamps issued over papers posted. In weight, 187 tons of paper and print pass up and down the ingenious " lift" every week, and thence to the uttermost corners of the earth—from Blackfriars to Botany Bay, from the Strand to Chusan.

The system of stamping, sorting, and arranging, is precisely similar to that in the District Branch; and, by his recently acquired knowledge of it, the person who posted the coloured letters was able to trace them through every stage, till they were tied up ready to be " bagged," and sent away.

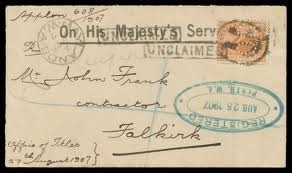

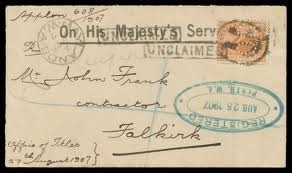

In an opposite side of the enormous apartment, a good space and a few officials are devoted to repairing the carelessness of the public, which is, in amount and extent, scarcely credible. Upon an average, 300 letters per day pass through the General Post-office totally unfastened; chiefly in consequence of the use of what stationers are pleased to call " adhesive" envelopes. Many are virgin ones, without either seal or direction; and not a few contain money. In Sir Francis Freeling's time, the sum of 5000 pounds in Bank-notes was found in a " blank." It was not till after some trouble that the sender was traced, and the cash restored to him. Not long since, an humble post-mistress of an obscure Welsh post-town, unable to decipher the address on a letter, perceived, on examining it, the folds of several Bank-notes protruding from a torn edge of the envelope. She securely re-enclosed it to the secretary of the Post-office in St. Martin's-le-Grand; who found the contents to be 1500 pounds, and the superscription too much even for the hieroglyphic powers of the

"blind clerk." Eventually the enclosures found their true destination.

It is estimated that there lies, from time to time, in the Dead-Letter-office, undergoing the process of finding owners, some 11,0007. annually, in cash alone. In July, 1847, for instance—only a two months' accumulation— ,the post-haste of 4658 letters, all containing property, was arrested by the bad superscriptions of the writers. They were consigned—after a searching inquest upon each by that efficient coroner, the " blind clerk"—to the Post-office Morgue. There were Banknotes of the value of 10107., and money-orders for 4077. 12s. But most of these ill-directed letters contained coin in small sums, amounting to 3107. 9s. 7d. On the 17th of July, 1847, there were lying in the Dead-Letter-office bills of exchange for the immense sum of 40,4107. 5s. 7d.

"I assure you," said a gentleman high in this department, " it is scarcely possible to take up a handful of letters without finding one with coin in it, despite the facilities afforded by the money-order system. All this is very distressing to us. The temptation it throws in the way of sorters, carriers, and other humble employes is greater than they ought to be subjected to. Seventy men have been discharged for dishonesty from the District-office alone during the past two years."

"But the public do use the Money-Order-office extensively?"

This question was startlingly answered by reference to a Parliamentary return, which showed that there were issued in England and Wales alone, during the year which ended on the 5th of January, 1849, 3,468,823 Post-office orders for sums amounting to the enormous aggregate of 6,861,803 pounds.

It was approaching eight o'clock, and the "Miller and his Men" above stairs were delivering their sacks from the mouth of the ever-revolving mill at an incessant rate. These, filled nearly to choking with newspapers, were dragged to the tables, which the brass label fastened to the corner of each bag marked as its own, to have the letters inserted. Our friends rushed to where they saw "Edinburgh" painted up on the walls, and there they beheld their yellow, green, and red letters in separate packets, though destined for the same place; just as they had come in at first from Fleet-street. The bundles were popped in a trice into the Edinburgh bag, which was sealed and sent away. Exactly the same thing was happening to every bundle of letters, and to every bag on the premises.

The clock now struck eight, and the two visitors looked round in astonishment. Had they been guests at the ball in " Cinderella," when that clock struck they would not have been more astonished; for hardly less rapidly did the fancy dresses of the postmen disappear, and the lights grow dim. This is the most striking peculiarity of the extraordinary establishment. Everything is done on military principles to minute time. The drill and subdivision of duties are so perfect that the alternations throughout the day are high pressure and sudden collapse. At five minutes before eight the enormous offices were glaring with light and crowded with men; at ten minutes after eight the glass slipper had fallen off, and there was hardly a light or a living being visible.

"Perhaps, however," it was remarked, as our friends were leaving the building, " an invisible individual is now stealthily watching behind the ground glass screen. Only the other day he detected from it a sorter secreting 140 sovereigns."

It is a deplorable thing that such a place of observation should be necessary; but it is hardly less deplorable—and this should be most earnestly impressed upon the reader—that the public, now possessed of such conveniences for remitting money, by means of Post-office Orders and Registered Letters, should lightly throw temptation in the way of these clerks by enclosing actual coin. No man can say that, placed in such circumstances from day to day, he could be steadfast. Many may hope they would be, and believe it; but none can be sure. It is in the power, however, of-every conscientious and reflecting mind to make quite sure that it has no part in this class of crimes. The prevention for this one great source of misery is made easy to the public hand, and it is the public's bounden duty to adopt it. They who do not, cannot be blameless.

Such is the substance of information obtained by our friends before they took leave of the mighty heart of the postal system of this country.

The End

The piece follows the progress of two gentlemen who make a visit to the Post Office and Part Three continues -

The friends were informed that 70,000,000 newspapers pass through all the post-offices every year. Upwards of 80,000,000 newspaper stamps are distributed annually from the Stamp office; but, most of the London papers are conveyed into the country by early trains. On the other hand, frequently the same paper passes through the post several times, which accounts for the small excess of 10,000,000 stamps issued over papers posted. In weight, 187 tons of paper and print pass up and down the ingenious " lift" every week, and thence to the uttermost corners of the earth—from Blackfriars to Botany Bay, from the Strand to Chusan.

The system of stamping, sorting, and arranging, is precisely similar to that in the District Branch; and, by his recently acquired knowledge of it, the person who posted the coloured letters was able to trace them through every stage, till they were tied up ready to be " bagged," and sent away.

In an opposite side of the enormous apartment, a good space and a few officials are devoted to repairing the carelessness of the public, which is, in amount and extent, scarcely credible. Upon an average, 300 letters per day pass through the General Post-office totally unfastened; chiefly in consequence of the use of what stationers are pleased to call " adhesive" envelopes. Many are virgin ones, without either seal or direction; and not a few contain money. In Sir Francis Freeling's time, the sum of 5000 pounds in Bank-notes was found in a " blank." It was not till after some trouble that the sender was traced, and the cash restored to him. Not long since, an humble post-mistress of an obscure Welsh post-town, unable to decipher the address on a letter, perceived, on examining it, the folds of several Bank-notes protruding from a torn edge of the envelope. She securely re-enclosed it to the secretary of the Post-office in St. Martin's-le-Grand; who found the contents to be 1500 pounds, and the superscription too much even for the hieroglyphic powers of the

"blind clerk." Eventually the enclosures found their true destination.

It is estimated that there lies, from time to time, in the Dead-Letter-office, undergoing the process of finding owners, some 11,0007. annually, in cash alone. In July, 1847, for instance—only a two months' accumulation— ,the post-haste of 4658 letters, all containing property, was arrested by the bad superscriptions of the writers. They were consigned—after a searching inquest upon each by that efficient coroner, the " blind clerk"—to the Post-office Morgue. There were Banknotes of the value of 10107., and money-orders for 4077. 12s. But most of these ill-directed letters contained coin in small sums, amounting to 3107. 9s. 7d. On the 17th of July, 1847, there were lying in the Dead-Letter-office bills of exchange for the immense sum of 40,4107. 5s. 7d.

"I assure you," said a gentleman high in this department, " it is scarcely possible to take up a handful of letters without finding one with coin in it, despite the facilities afforded by the money-order system. All this is very distressing to us. The temptation it throws in the way of sorters, carriers, and other humble employes is greater than they ought to be subjected to. Seventy men have been discharged for dishonesty from the District-office alone during the past two years."

"But the public do use the Money-Order-office extensively?"

This question was startlingly answered by reference to a Parliamentary return, which showed that there were issued in England and Wales alone, during the year which ended on the 5th of January, 1849, 3,468,823 Post-office orders for sums amounting to the enormous aggregate of 6,861,803 pounds.

It was approaching eight o'clock, and the "Miller and his Men" above stairs were delivering their sacks from the mouth of the ever-revolving mill at an incessant rate. These, filled nearly to choking with newspapers, were dragged to the tables, which the brass label fastened to the corner of each bag marked as its own, to have the letters inserted. Our friends rushed to where they saw "Edinburgh" painted up on the walls, and there they beheld their yellow, green, and red letters in separate packets, though destined for the same place; just as they had come in at first from Fleet-street. The bundles were popped in a trice into the Edinburgh bag, which was sealed and sent away. Exactly the same thing was happening to every bundle of letters, and to every bag on the premises.

The clock now struck eight, and the two visitors looked round in astonishment. Had they been guests at the ball in " Cinderella," when that clock struck they would not have been more astonished; for hardly less rapidly did the fancy dresses of the postmen disappear, and the lights grow dim. This is the most striking peculiarity of the extraordinary establishment. Everything is done on military principles to minute time. The drill and subdivision of duties are so perfect that the alternations throughout the day are high pressure and sudden collapse. At five minutes before eight the enormous offices were glaring with light and crowded with men; at ten minutes after eight the glass slipper had fallen off, and there was hardly a light or a living being visible.

"Perhaps, however," it was remarked, as our friends were leaving the building, " an invisible individual is now stealthily watching behind the ground glass screen. Only the other day he detected from it a sorter secreting 140 sovereigns."

It is a deplorable thing that such a place of observation should be necessary; but it is hardly less deplorable—and this should be most earnestly impressed upon the reader—that the public, now possessed of such conveniences for remitting money, by means of Post-office Orders and Registered Letters, should lightly throw temptation in the way of these clerks by enclosing actual coin. No man can say that, placed in such circumstances from day to day, he could be steadfast. Many may hope they would be, and believe it; but none can be sure. It is in the power, however, of-every conscientious and reflecting mind to make quite sure that it has no part in this class of crimes. The prevention for this one great source of misery is made easy to the public hand, and it is the public's bounden duty to adopt it. They who do not, cannot be blameless.

Such is the substance of information obtained by our friends before they took leave of the mighty heart of the postal system of this country.

The End

Published on February 23, 2011 01:09

February 22, 2011

Sending Our Prayers

Number One London has many regular visitors from New Zealand and Victoria and I want to take this opportunity to let you all know that our thoughts are with you during the aftermath of the earthquake, which struck Christchurch at 12.51pm on Tuesday local time.

The Queen, who is also New Zealand's head of state, expressed her sadness at the 6.3 magnitude quake, saying she was "utterly shocked" by the news.

"Please convey my deep sympathy to the families and friends of those who have been killed; my thoughts are with all those who have been affected by this dreadful event," she said.

"My thoughts are also with the emergency services and everyone who is assisting in the rescue efforts."

We pray that you and yours are safe.

Published on February 22, 2011 05:53

The London Post Office 1850 - Part Two

In this series, we turn to the words of Mr. Charles Dickens which appeared in the March 30, 1850 edition of the publication he edited, Household Words. The following article is chock full of details about how the Post Office operated in Victorian London and also about the mail and other items it processed on a daily basis.

The piece follows the progress of two gentlemen who make a visit to the Post Office and Part Two continues -

" Is it possible?" exclaimed one of the visitors, regarding the piles of epistles on the numerous tables "that this mass of letters can be arranged and sent away to their respective addresses in time to receive the next collection, which will arrive in less than an hour?"

"Quite," replied an obliging informant; " I'll tell you how we do it. We have divided London into seventeen sections. There they are, you perceive." He then pointed to the tables with pigeon-holes numbered from one to seventeen; one marked "blind," with a nineteenth labelled "general." It was explained that the proper arrangement of the letters in these compartments constitutes the first sorting. They are then sorted into subdivisions; then into districts, and finally handed over to the letter-carriers, who, in another room, arrange them for their own convenience into " walks." As the visitors looked round they perceived their coloured envelopes—which were all addressed to Scotland, suddenly emerge from a chaotic heap, and lodged in the division marked " general," as magically as a conjuror causes any card you may choose to fly out of the whole pack. "These letters," remarked the expositor, "being for the country, will be presently passed into the Inland-office through a tunnel under the hall. " The ' blind' letters have superscriptions which the sorters cannot decipher, and are sent to the ' blind' table, where a gentleman presides, to whom, from the extreme sharpness of his vision, we give the lucus a non lucendo name of the ' blind clerk.' You will have a specimen of his powers presently."

While this dialogue was going on there was a general abatement of the noise of stamping and shuffling letters; and, when the visitors looked round, the place had relapsed into its former tranquillity. It was scarcely credible that from 30,000 to 40,000 letters had been received, stamped, counted, sorted, and sent away in so short a time. "A judicious division of labour," remarked one of our friends, " must work these miracles."

"Yes, sir," was the reply of an official. "There are from 1200 to 1700 of us to do the work of the district post alone. When it was removed from Gerrard-street to this building there was not a quarter of that number. For instance—then, three carriers sufficed for the Paddington district; but, by the despatch you have just seen completed, we have sent off 2000 letters to that single locality by the hands of twenty-five carriers."

" The increase is attributable to the penny system?" interrogated one of our inquiring friends.

" Entirely."

The questioner then referred to a Parliamentary paper of which he had obtained possession. It showed him the history of general postal increase since the era of dear distance rates. In 1839—under the old system—the number of letters which passed through the post was 76 millions. In 1840 came the uniform penny, and for that year the number was 162 millions, or an increase of 93 millions, equal to 123 per cent. That was the grand start; afterwards the rate of increase subsided from 36 per cent. in 1841, to 16 per cent. in 1842 and 1843. In 1845, and the three following years, the increase was respectively, 39, 37, and 30 per cent. Then succeeded a sudden drop; perhaps the culminating point in the rate of increase had been attained. The Post-office is, however, a thermometer of commerce: during the depressing year 1848, the number of letters increased no more than 9 per cent. But last year 337,500,000 epistles passed through the office, being an augmentation of 8,500,000 upon the preceding year, or 11 per cent, of progressive increase. Another Parliamentary document shows, that, although the business is now four and a half times more than it was in 1839, the expense of doing it has only doubled. In the former year the cost of the establishment was not quite 690,000/.; in 1849 it was about 1,400,000/.

While one visitor was poring over these documents, the other deliberately watched the coloured envelopes. They were, with about 2000 other General Post letters, put into boxes and taken to the tunnel to be conveyed into the Inlandoffice upon a horizontal band worked by a wheel. The two friends now took leave of the District Department to follow the objects of their pursuit.

It was a quarter before six o'clock when they crossed the Hall—six being the latest hour at which newspapers can be posted without fee.

It was then just drizzling newspapers. The great window of that department being thrown open, the first black fringe of a thunder-cloud of newspapers impending over the Post office was discharging itself fitfully—now in large drops, now in little; now in sudden plumps, now stopping altogether. By degrees it began to rain hard; by fast degrees the storm came on harder and harder, until it blew, rained, hailed, snowed, newspapers. A fountain of newspapers played in at the window. Water-spouts of newspapers broke from enormous sacks, and engulphed the men inside. A prodigious main of newspapers, at the Newspaper River Head, seemed to be turned on, threatening destruction to the miserable Post-office. The Post-office was so full already, that the window foamed at the mouth with newspapers. Newspapers flew out like froth, and were tumbled in again by the bystanders. All the boys in London seemed to have gone mad, and to be besieging the Post-office with newspapers. Now and then there was a girl; now and then a woman; now and then a weak old man: but as the minute hand of the clock crept near to six, such a torrent of boys, and such a torrent of newspapers came tumbling in together pell-mell, head over heels, one above another, that the giddy head looking on chiefly wondered why the boys springing over one another's heads, and flying the garter into the Post-office with the enthusiasm of the corps of acrobats at M. Franconi's, didn't post themselves nightly, along with the newspapers, and get delivered all over the world.

Suddenly it struck six. Shut, Sesame! Perfectly still weather. Nobody there. No token of the late storm—Not a soul, too late!

But what a chaos within! Men up to their knees in newspapers on great platforms; men gardening among newspapers with rakes; men digging and delving among newspapers as if a new description of rock had been blasted into those fragments ; men going up and down a gigantic trap—an ascending and descending-room worked by a steam-engine—still taking with them nothing but newspapers. All the history of the time, all the chronicled births, deaths, and marriages, all the crimes, all the accidents, all the vanities, all the changes, all the realities, of all the civilised earth, heaped up, parcelled out, carried about, knocked down, cut, shuffled, dealt, played, gathered up again, and passed from hand to hand, in an apparently interminable and hopeless confusion, but really in a system of admirable order, certainty, and simplicity, pursued six nights every week, all through the rolling year. Which of us, after this, shall find fault with the rather more extensive system of good and evil, when we don't quite understand it at a glance; or set the stars right in their spheres?

Part Three Coming Soon!

The piece follows the progress of two gentlemen who make a visit to the Post Office and Part Two continues -

" Is it possible?" exclaimed one of the visitors, regarding the piles of epistles on the numerous tables "that this mass of letters can be arranged and sent away to their respective addresses in time to receive the next collection, which will arrive in less than an hour?"

"Quite," replied an obliging informant; " I'll tell you how we do it. We have divided London into seventeen sections. There they are, you perceive." He then pointed to the tables with pigeon-holes numbered from one to seventeen; one marked "blind," with a nineteenth labelled "general." It was explained that the proper arrangement of the letters in these compartments constitutes the first sorting. They are then sorted into subdivisions; then into districts, and finally handed over to the letter-carriers, who, in another room, arrange them for their own convenience into " walks." As the visitors looked round they perceived their coloured envelopes—which were all addressed to Scotland, suddenly emerge from a chaotic heap, and lodged in the division marked " general," as magically as a conjuror causes any card you may choose to fly out of the whole pack. "These letters," remarked the expositor, "being for the country, will be presently passed into the Inland-office through a tunnel under the hall. " The ' blind' letters have superscriptions which the sorters cannot decipher, and are sent to the ' blind' table, where a gentleman presides, to whom, from the extreme sharpness of his vision, we give the lucus a non lucendo name of the ' blind clerk.' You will have a specimen of his powers presently."

While this dialogue was going on there was a general abatement of the noise of stamping and shuffling letters; and, when the visitors looked round, the place had relapsed into its former tranquillity. It was scarcely credible that from 30,000 to 40,000 letters had been received, stamped, counted, sorted, and sent away in so short a time. "A judicious division of labour," remarked one of our friends, " must work these miracles."

"Yes, sir," was the reply of an official. "There are from 1200 to 1700 of us to do the work of the district post alone. When it was removed from Gerrard-street to this building there was not a quarter of that number. For instance—then, three carriers sufficed for the Paddington district; but, by the despatch you have just seen completed, we have sent off 2000 letters to that single locality by the hands of twenty-five carriers."

" The increase is attributable to the penny system?" interrogated one of our inquiring friends.

" Entirely."

The questioner then referred to a Parliamentary paper of which he had obtained possession. It showed him the history of general postal increase since the era of dear distance rates. In 1839—under the old system—the number of letters which passed through the post was 76 millions. In 1840 came the uniform penny, and for that year the number was 162 millions, or an increase of 93 millions, equal to 123 per cent. That was the grand start; afterwards the rate of increase subsided from 36 per cent. in 1841, to 16 per cent. in 1842 and 1843. In 1845, and the three following years, the increase was respectively, 39, 37, and 30 per cent. Then succeeded a sudden drop; perhaps the culminating point in the rate of increase had been attained. The Post-office is, however, a thermometer of commerce: during the depressing year 1848, the number of letters increased no more than 9 per cent. But last year 337,500,000 epistles passed through the office, being an augmentation of 8,500,000 upon the preceding year, or 11 per cent, of progressive increase. Another Parliamentary document shows, that, although the business is now four and a half times more than it was in 1839, the expense of doing it has only doubled. In the former year the cost of the establishment was not quite 690,000/.; in 1849 it was about 1,400,000/.

While one visitor was poring over these documents, the other deliberately watched the coloured envelopes. They were, with about 2000 other General Post letters, put into boxes and taken to the tunnel to be conveyed into the Inlandoffice upon a horizontal band worked by a wheel. The two friends now took leave of the District Department to follow the objects of their pursuit.

It was a quarter before six o'clock when they crossed the Hall—six being the latest hour at which newspapers can be posted without fee.

It was then just drizzling newspapers. The great window of that department being thrown open, the first black fringe of a thunder-cloud of newspapers impending over the Post office was discharging itself fitfully—now in large drops, now in little; now in sudden plumps, now stopping altogether. By degrees it began to rain hard; by fast degrees the storm came on harder and harder, until it blew, rained, hailed, snowed, newspapers. A fountain of newspapers played in at the window. Water-spouts of newspapers broke from enormous sacks, and engulphed the men inside. A prodigious main of newspapers, at the Newspaper River Head, seemed to be turned on, threatening destruction to the miserable Post-office. The Post-office was so full already, that the window foamed at the mouth with newspapers. Newspapers flew out like froth, and were tumbled in again by the bystanders. All the boys in London seemed to have gone mad, and to be besieging the Post-office with newspapers. Now and then there was a girl; now and then a woman; now and then a weak old man: but as the minute hand of the clock crept near to six, such a torrent of boys, and such a torrent of newspapers came tumbling in together pell-mell, head over heels, one above another, that the giddy head looking on chiefly wondered why the boys springing over one another's heads, and flying the garter into the Post-office with the enthusiasm of the corps of acrobats at M. Franconi's, didn't post themselves nightly, along with the newspapers, and get delivered all over the world.

Suddenly it struck six. Shut, Sesame! Perfectly still weather. Nobody there. No token of the late storm—Not a soul, too late!

But what a chaos within! Men up to their knees in newspapers on great platforms; men gardening among newspapers with rakes; men digging and delving among newspapers as if a new description of rock had been blasted into those fragments ; men going up and down a gigantic trap—an ascending and descending-room worked by a steam-engine—still taking with them nothing but newspapers. All the history of the time, all the chronicled births, deaths, and marriages, all the crimes, all the accidents, all the vanities, all the changes, all the realities, of all the civilised earth, heaped up, parcelled out, carried about, knocked down, cut, shuffled, dealt, played, gathered up again, and passed from hand to hand, in an apparently interminable and hopeless confusion, but really in a system of admirable order, certainty, and simplicity, pursued six nights every week, all through the rolling year. Which of us, after this, shall find fault with the rather more extensive system of good and evil, when we don't quite understand it at a glance; or set the stars right in their spheres?

Part Three Coming Soon!

Published on February 22, 2011 01:00

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.