Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 153

April 9, 2011

Madame Tussaud - The Novel

Kristine's post about the Duke of Wellington visiting the wax museum has inspired me (Victoria) to write about a book I recently enjoyed: Madame Tussaud by Michelle Moran. It is a fictional biography, well-researched but using the kind of emotional depth and intimacy of fiction. I found the book fascinating and very well-written. I admit I have never been to one of Madame Tussaud's institutions; I would love to see the historical personages, but I have always assumed there was a lot more attention to current rock and film stars -- and I wouldn't recognize them much less care about them. I guess I have always classified wax museums as tourist traps. I know lots of people love them -- but I'm not a fan of the institution.

Kristine's post about the Duke of Wellington visiting the wax museum has inspired me (Victoria) to write about a book I recently enjoyed: Madame Tussaud by Michelle Moran. It is a fictional biography, well-researched but using the kind of emotional depth and intimacy of fiction. I found the book fascinating and very well-written. I admit I have never been to one of Madame Tussaud's institutions; I would love to see the historical personages, but I have always assumed there was a lot more attention to current rock and film stars -- and I wouldn't recognize them much less care about them. I guess I have always classified wax museums as tourist traps. I know lots of people love them -- but I'm not a fan of the institution.However, reading the story of Marie Grosholtz and her family gave me a true appreciation of what they were trying to accomplish with their salon, including making a lot of money, and the lengths to which they went to conform to popular trends in a time of incredible turmoil.

Michelle Moran is the author of several historical novels. Click here for her website. The picture left shows Ms. Moran (r) with the figure of her subject, Madame Tussaud, at the Hollywood Museum. I have read reports of a film of the book in the works. And why not? Madame lived a long, event-filled life. Marie Grosholtz was born in 1761 in Strasbourg. Her widowed mother took her to Bern, Switzerland, where they lived in the household of Dr. Curtius, a physician who specialized in creating wax models, first for teaching purposes, eventually for exhibition. They moved to Paris in 1765 and Dr. Curtius began to exhibit his figures in lifelike settings. Marie was an eager student and by the time she was a teen, she began to mold and scuplt the heads of famous persons for their exhibit. She also spent time with the royal family at Versailles, teaching the king's sister to scuplt saints. While she split her time between the sumptuous royal palace and Dr. Curtius's house, associates of her family were involved in the tumult leading up to the Revolution.

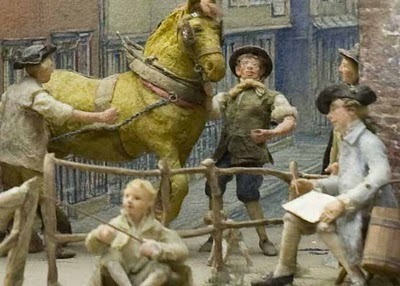

Michelle Moran is the author of several historical novels. Click here for her website. The picture left shows Ms. Moran (r) with the figure of her subject, Madame Tussaud, at the Hollywood Museum. I have read reports of a film of the book in the works. And why not? Madame lived a long, event-filled life. Marie Grosholtz was born in 1761 in Strasbourg. Her widowed mother took her to Bern, Switzerland, where they lived in the household of Dr. Curtius, a physician who specialized in creating wax models, first for teaching purposes, eventually for exhibition. They moved to Paris in 1765 and Dr. Curtius began to exhibit his figures in lifelike settings. Marie was an eager student and by the time she was a teen, she began to mold and scuplt the heads of famous persons for their exhibit. She also spent time with the royal family at Versailles, teaching the king's sister to scuplt saints. While she split her time between the sumptuous royal palace and Dr. Curtius's house, associates of her family were involved in the tumult leading up to the Revolution. The events of these days are well chronicled by Moran as seeen through the eyes of Marie, a young woman in her late twenties, searching for love, yet obsessed with perfecting her art and making money. During the Reign of Terror, she accommodated the mob by creating death masks from heads fresh from the guillotine. At right, one of the displays from the wax museum. Ugh. However, she felt some loyalty to King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, deploring the chaos when they fell.

The events of these days are well chronicled by Moran as seeen through the eyes of Marie, a young woman in her late twenties, searching for love, yet obsessed with perfecting her art and making money. During the Reign of Terror, she accommodated the mob by creating death masks from heads fresh from the guillotine. At right, one of the displays from the wax museum. Ugh. However, she felt some loyalty to King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, deploring the chaos when they fell.  Marie spent time in the prison that held the future Empress Josephine and Grace Elliot, mistress of the Duc d'Orleans. Though both Josephine's first husband and the Duc lost their heads, the three women were among the survivors. While in prison, Marie met Francois Tussaud, and they married after the Terror came to an end. It was not a happy marriage; he succumbed to drink and gambling, and was a constant drag on her accomlishments. In 1802, Madame Tussaud and her elder son took some of their figures on tour to England, where they stayed and established the wax museum that still bears her name.

Marie spent time in the prison that held the future Empress Josephine and Grace Elliot, mistress of the Duc d'Orleans. Though both Josephine's first husband and the Duc lost their heads, the three women were among the survivors. While in prison, Marie met Francois Tussaud, and they married after the Terror came to an end. It was not a happy marriage; he succumbed to drink and gambling, and was a constant drag on her accomlishments. In 1802, Madame Tussaud and her elder son took some of their figures on tour to England, where they stayed and established the wax museum that still bears her name.At left, wax figures of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI. Eventually, after her husband's death, she was reunited with her mother and her second son. She ran her business with her sons until her death in 1850.

Going back to the proposed movie of Madame Tussaud, the costumes are already available, and they even won an oscar for the designers who worked on Sofia Coppola's 2006 film Marie Antoinette. I remember my very ambiguous reaction to this movie. The youthful queen was such a Valley Girl, so frivolous and, frankly, stupid, I could hardly bear it. Yet I realize she might very well have been such a little fool. Certainly as portrayed by Michelle Moran, she made some very poor decisions. But the costumes and settings and the composition of the shots -- all were brilliant.

I think I will get the DVD and watch it with the sound off. I not only

I think I will get the DVD and watch it with the sound off. I not onlydespised the dialogue and how it was delivered, but I seem to recall a quite jarring musical track. Please send in your views of this movie.

Anyway, I'd love to see those brilliant costumes again. Haven't we learned that in all the Jane Austen films and tv series, the British reuse the costumes over and over? I seem to recall a fun blog post by someone listing which dress was worn where. Did I mention the sets? And the gardens. Much of the movie was actually filmed in Versailles and in its gardens.

One of the books Michelle Moran used as a resource for her novel Madame Tussaud is Antonia Fraser's Marie Antoinette. As a long-time admirer of Fraser's books, both her historical works and the detective series, I think I will briefly turn my back on British bios and try this one.

One of the books Michelle Moran used as a resource for her novel Madame Tussaud is Antonia Fraser's Marie Antoinette. As a long-time admirer of Fraser's books, both her historical works and the detective series, I think I will briefly turn my back on British bios and try this one.And just to prove that everything on this blog really can be traced back to the Duke of Welllington, Lady Antonia was born into the family Pakenham, one and the same with the 1st Duchess of Wellington. Fraser is the daughter of Elizabeth Longford, biographer of the Duke, whose two-volume work has never been surpassed for insight into the life of the great man.

Published on April 09, 2011 02:00

April 8, 2011

The Ill Fated Marriage of George IV

On 8 April 1795 at the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace took place the marriage of The Prince of Wales to his cousin, Princess Caroline of Brunswick. No love match, the Prince was marrying Caroline in exchange for Parliament's agreement to pay off his astronomical debts. In fact, the Prince had previously, and quasi-secretly, married Maria Fitzherbert on 15 December 1785, in the drawing room of her house in Park Street, London. Whilst the marriage wasn't announced with a public hue and cry, it was still public knowledge.

From Mrs. Fitzherbert and George IV by William Henry Wilkins (1905):

The denials of the Prince's friends counted for little, for people remembered how emphatically the rumour of the marriage between the Duke of Gloucester and Lady Waldegrave had been denied, and yet it proved to be true after all. The accounts of Mrs. Fitzherbert's marriage were categorical, and the fact that she was supported and visited by many ladies of the first fashion lent the weight of corroborative evidence. With the public the opinion gained ground that a marriage had taken place. The Marquis of Lothian wrote to the Duke of Rutland, March 4, 1786, "You ask me my opinion respecting the Prince's marriage. I think it has all the appearance of being true. I believe, when he has been spoken to about it, he has been violent, but I cannot find out that he has denied it peremptorily. He has said to one of the most intimate in his family [household], when asked on the subject, that he might answer, if asked the question, in the negative. But surely a report of this sort, were it not true, should be publicly contradicted, and I am amazed that some member of Parliament has not mentioned it in the House. Most people believe it, and I confess I am one of the number. Though I dined alone with him, and you know the general topic of his conversation about women, he never mentioned her to me amongst others. I am very sorry for it, for it does him infinite mischief, particularly amongst the trading and lower sort of people, and if true must ruin him in every light."

Maria Fitzherbert

Maria FitzherbertIt may be supposed that the topic was not confined to private letters. The press, then far less restrained than now, continued to teem with scarcely veiled innuendoes and scandalous rumours. Some journals maintained that "some sort of marriage" had taken place, others stoutly denied it. Nor did the caricaturists, those inevitable satirists on the follies of the day, linger behind. Prints and cartoons on the subject of the marriage were published in great number and variety; they were exposed in the shop windows, and even sold in the streets, to the great delight of the vulgar. All, or nearly all, of them were wide of the facts, and many were exceedingly scurrilous. It was an age of coarseness, and the licence permitted to the caricaturists was great.

Rumour and innuendo aside, the marriage was illegal, as under the Royal Marriage Act, the Prince of Wales, being below the age of 25, could not marry without the Kng's permission. He most especially could not marry a Roman Catholic. Now, there's alot more to the story - much more than we have room for in this post - but suffice to say that George, Prince of Wales was fairly forced by his father, King George III, to settle down, to marry and to beget himself an heir. Unfortunately, George loathed Princess Caroline on sight, taking offence at her looks, her voice, her personality, her manner and, it seems fair to say, her very existence.

Nevertheless, the marriage ceremony which took place on April 8th, at which the Prince of Wales was attended by three unmarried groomsmen including: the 30-year-old friend the 5th Duke of Bedford and the 3rd Duke of Roxburghe, a 54-year-old favorite of George III. The Prince was also attended by his friend, the 17-year-old Coronet George "Beau" Brummell. And whilst he was not attended by her, also present was the Prince's current mistress, Frances, Lady Jersey.

Caroline, 1804 by Sir Thomas Lawrence

Caroline, 1804 by Sir Thomas Lawrence The Prince of Wales arrived for the wedding very drunk and was obviously reluctant to proceed with the ceremony, hesitated frequently in his responses and cried openly in front of the company. In fact, at one point in the ceremony, his father actually had to urge him to say his lines and get the business concluded. The Prince looked not at all at his bride but frequently at his mistress, the 42-year-old Lady Jersey, the wife of the 60-year-old fourth Earl of Jersey, George Bussy Villiers.

After the ceremony, the King and Queen held a drawing-room for the couple in the Queen's apartment in St. James Palace. Caroline seemed pleased and chatty. The Prince was silent and morose until near the end of the evening when he recovered his composure enough to become "very civil and gracious." This upturn did not last long, as soon the Prince of Wales became so drunk that he spent his wedding night passed out on the floor in front of the bedroom fireplace. He finally awakened early in the morning and performed his conjugal duties, which resulted in a daughter, Princess Charlotte, nine months later when, coincidentally, the couple split up, never again to live as man and wife.

Published on April 08, 2011 03:03

April 7, 2011

From the Pen of Horace Walpole

Princess Amalie

Princess Amalie A Letter from Horace Walpole to the Earl of HertfordStrawberry Hill, Easter Sunday, April 7, 1760

Your first wish will be to know how the King does: he came to Richmond last Monday for a week; but appeared suddenly and unexpected at his levee at St . James's last Wednesday; this was managed to prevent a crowd. Next day he was at the drawing-room, and at chapel on Good Friday. They say, he looks pale; but it is the fashion to call him very well:—I wish it may be true. The Duke of Cumberland is actually set out for Newmarket to-day: he too is called much better; but it is often as true of the health of princes as of their prisons, that there is little distance between each and their graves. There has been a fire at Gunnersbury, which burned four rooms: her servants announced it to Princess Amalie (daughter of King George III) with that wise precaution of "Madam, don't be frightened!—" accordingly, she was terrified. When they told her the truth, she said, "I am very glad; I had concluded my brother was dead."—So much for royalties!

Northumberland House

Northumberland House. . . . . Now, for my disaster; you will laugh at it, though it was woeful to me. I was to dine at Northumberland-house, and went a little after hour: there I found the Countess, Lady Betty Mekinsy, Lady Strafford; my Lady Finlater, who was never out of Scotland before; a tall lad of fifteen, her son; Lord Drogheda, and Mr. Worseley. At five, arrived Mr. Mitchell, who said the Lords had begun to read the Poorbill, which would take at least two hours, and perhaps would debate it afterwards. We concluded dinner would be called for, it not being very precedented for ladies to wait for gentlemen:—no such thing. Six o'clock came,—seven o'clock came,— our coaches came,— well! we sent them away, and excuses were we were engaged. Still the Countess's heart did not relent, nor uttered a syllable of apology. We wore out the wind and the weather, the opera and the play, Mrs. Cornelys's and Almack's, and every topic that would do in a formal circle. We hinted, represented—in vain. The clock struck eight: my lady, at last, said, she would go and order dinner; but it was a good half-hour before it appeared. We then sat down to a table for fourteen covers; but instead of substantiate, there was nothing but a profusion of plates striped red, green, and yellow, gilt plate, blacks and uniforms!

James Ogilvy, 5th Earl of Findlater

James Ogilvy, 5th Earl of Findlater My Lady Finlater, who had never seen these embroidered dinners, nor dined after three, was famished. The first course stayed as long as possible, in hopes of the lords: so did the second. The dessert at last arrived, and the middle dish was actually set on when Lord Finlater and Mr. Mackay arrived! — would you believe it?—the dessert was remanded, and the whole first course brought back again !— Stay, I have not done:—just as this second first course had done its duty, Lord Northumberland, Lord Strafford, and Mekinsy came in, and the whole began a third time! Then the second course, and the dessert! I thought we should have dropped from our chairs with fatigue and fumes! When the clock struck eleven, we were asked to return to the drawing-room, and drink tea and coffee, but I said I was engaged to supper, and came home to bed. My dear lord, think of four hours and a half in a circle of mixed company, and three great dinners, one after another, without interruption;—no, it exceeded our day at Lord Archer's! Mrs. Armiger, and Mrs. Southwell, Lady Gower's niece, are dead, and old Dr. Young, the poet. Good night!

Published on April 07, 2011 01:12

April 6, 2011

Upstairs, Downstairs Returns!

Over the past four decades, the original series of Upstairs, Downstairs has been watched by more than one billion people in more than 40 countries, inspiring a whole new generation of period dramas, including the recent PBS series Downton Abbey. Seemingly the whole of England sat round their tellies on Sunday nights following the fortunes of the Bellamy Family. When the series ended in 1977, Alistair Cooke, the program's host, declared that there should be a national day of mourning. This Sunday night, for the first time since it went off the air, Upstairs, Downstairs will debut three new episodes (with more to follow in 2012), providing a long-awaited sequel to the original series, which followed the aristocratic Bellamys and their below-stairs help from the pre-First World War era to the 1930 market crash.

Co-produced by the BBC and Masterpiece on PBS, the latest Upstairs, Downstairs picks up in 1936 with an all-new cast joining the series' co-creator and star Jean Marsh, who plays Rose once again. Series co-creator Eileen Atkins (Cranford) also stars, as do Keeley Hawes, Ed Stoppard and Art Malik (The Jewel in the Crown).

The new series opens with a new couple moving into 165 Eaton Place, requiring the help of Rose, who's now the proprietor of a domestic employment agency, with the hiring of servants. Their privileged lives are soon threatened by world affairs, including the abdication crisis of Edward VIII and the rise of fascism at home and abroad.

As the British series returns to the U.S. Sunday on PBS' "Masterpiece," only six years have passed since the day in 1930 when the last of the Bellamys and their servants vacated 165 Eaton Place, and yet Jean Marsh, who last starred as Rose 35 years ago, is still very much Rose.

"Thank you very much," Marsh replied when told so in a PBS news conference this past January.

"But the problem was when we were talking about it, I said, 'I'll need some help. You know, because it's 35 years, not six years.'

"And they said, 'Oh, yes, everything will be easy and wonderful and you look good,' and then it's on HD, which is so ferocious. I wasn't allowed to wear real makeup and the lighting was ferocious. And I looked and I thought, 'Oh, they'll all think that I'm 120."

Having already seen the new series when I was in London in December, I can heartily recommend it and am confident you won't be disappointed in this new production, airing in three parts on April 10, 17 and 24, 2011 at 9 p.m. A second series of Upstairs, Downstairs is in the works. Joy!

Of course, nothing can take the place of the original cast and the original series.

The original cast. (Poor Helen! Poor Captain James - the cad. And Ruby . . . no doubt still single. If only she'd put on a dab of lipstick . . . What's Mrs. Bridges cooking/baking? Smells lovely. And that Sarah, oh! Cheeky girl. Up to no good, she is. Has Miss Elizabeth returned yet from the States? And Lady Prudence, no doubt still dropping round for glasses of sherry . . . . )

You may recall that I made my own pilgrimage to (1)65 Eaton Place in December, when I took this photo -

Really, the cab driver thought I was mad. We were on our way to Paddington Station and I asked to stop in Eaton Place first so that I could take a picture of a certain house. Usually unfappable, this particular cabby couldn't hold his tongue as curiosity got the better of him. "What's so special about that address, then?" he asked. And I told him as I took a last look at the Bellamy house, hoping for a fleeting glimpse of Richard Bellamy. Or Mr. Hudson. Or even Rose herself. I'm happy to tell you that now we can all catch glimpses of the original characters whenever we like, as a special 40th Anniversary edition of the original series is now available for $130.99 ($50 - $60 less than at other sites) at Amazon. Click on the picture below for details. The set includes a bonus 25 hours of commentaries, interviews and extras. I ordered my copy yesterday, along with a DVD of the spin-off series, Thomas and Sarah.

Published on April 06, 2011 02:50

April 5, 2011

The Wellington Connection: Madame Tussaud

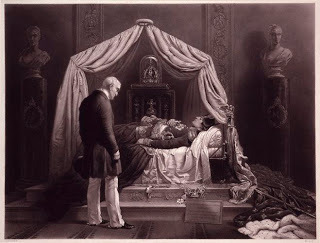

The Duke of Wellington visiting the Effigy and Personal Relics of Napoleon

The Duke of Wellington visiting the Effigy and Personal Relics of Napoleon at Madame Tussaud's by James Scott, after Sir George Hayter - National Portrait Gallery

Generally speaking, when one thinks about the Duke of Wellington, one seldom thinks of him in connection with trivial amusements. Rather, the formidable soldier and stern politician come to mind. However, the Duke was occasionally up for a jolly time and he had a great interest in new inventions and various amusements of the day. When the Great Exhibition of 1851 opened, the Duke went to see it nearly every day.

In Struggles and Triumphs: or, Forty Years' Recollections of P. T. Barnum by Phineas Taylor Barnum (1871), Mr. Barnum relates the following anecdote about the Duke:

"On my first return visit to America from Europe, I engaged Mr. Faber, an elderly and ingenious German, who had constructed an automaton speaker. It was of life-size, and when worked with keys similar to those of a piano, it really articulated words and sentences with surprising distinctness. My agent exhibited it for several months in Egyptian Hall, London, and also in the provinces. This was a marvellous piece of mechanism, though for some unaccountable reason it did not prove a success. The Duke of Wellington visited it several times, and at first he thought that the `voice' proceeded from the exhibitor, whom he assumed to be a skillful ventriloquist He was asked to touch the keys with his own fingers, and after some instruction in the method of operating, he was able to make the machine speak, not only in English but also in German, with which language the Duke seemed familiar. Thereafter, he entered his name on the exhibitor's autograph book, and certified that the `Automaton Speaker' was an extraordinary production of mechanical genius."

The Duke of Wellington was also a great fan of Madame Tussaud's and visited her waxworks often to see the exhibits and/or to take tea with Madame herself. He left standing instructions that he was to be told whenever a new addition to the rooms was installed. As executor of the will of George IV, Wellington was resposible for giving Madame Tussaud the monarch's coronation robes for her exhibit. Surprisingly, the Duke's favorite exhibit at the Wax Work was that of Napoleon. From a contemporary book titled The Curiosities of London, we learn that Madame Tussaud's Napoleon exhibit contained the following:

Napoleon Relics. — The camp-bedstead on which Napoleon died; the counterpane stained with his blood. Cloak worn at Marengo. Three eagles taken at Waterloo. Cradle of the King of Rome. Bronze posthumous cast of Napoleon, and hat worn by him. Whole-length portrait of the Emperor, from Fontainebleau; Marie Louis and Josephine, and other portraits of the Bonaparte family. Bust of Napoleon, by Canon. Isabey's portrait Table of the Marshals. Napoleon's three carriages: two from Waterloo, and a landau from St. Helena. His garden chair and drawing-room chair. "The flag of Elba." Napoleon's sword, diamond, tooth-brush, and table-knife; dessert knife, fork, and spoons; coffee-cup; a piece of willow-tree from St. Helena; shoe-sock and handkerchiefs, shirt, &c. Model figure of Napoleon in the clothes he wore at Longwood; and porcelain dessert-service used by him. Napoleon's hair and tooth, etc. As to Wellington's visits to the Exhibit, we have the following passage from The History Of Madame Tussaud's ( Originally Published 1920 ) -

Early one morning, soon after the Exhibition had been opened for the day, Joseph, Madame Tussaud's son, who had been wandering through the rooms, as was his habit, perceived an elderly gentleman in front of the tableau representing the lying-in-state of Napoleon I. The model of the dead exile rested—as it does down to this very day—on the camp bedstead used by Napoleon at St. Helena, and was dressed in the favourite green uniform, the cloak worn at Marengo (bequeathed by Napoleon to his son) lying across the feet. In the hands, crossed upon the chest, was a crucifix. In those days it was the custom to lower at night the curtains that enclosed the bed, in order to exclude the dust, whereas now the whole scene is encased in glass.

Observing that the visitor was desirous of seeing the effigy, and no attendant being at hand, Joseph Tussaud raised the hangings, whereupon the visitor removed his hat, and, to his great surprise, Joseph saw that he was face to face with none other than the great Duke of Wellington himself.

There stood his Grace, contemplating with feelings of mixed emotions the strange and suggestive scene before him. On the camp bed lay the mere presentment of the man who, seven-and-thirty years before, had given him so much trouble to subdue. No feeling of triumph passed through the conqueror's mind as he looked upon the poor waxen image, too true in its aspect of death; he rather thought upon the vanity of earthly triumphs, of the levelling hand of time, and how soon he, like his great contemporary, might be stretched upon his own bier.

Mr. Joseph Tussaud used frequently to recall this dramatic meeting between the Iron Duke and the effigy of his erstwhile foe, and to imagine the feelings of the old General as he gazed upon the couch. It was probably the first of the Duke's many visits to the Exhibition.

A few days after this most interesting visit Mr. Tussaud, who was an old friend of Sir George Hayter, related the incident to that artist. Hayter was immediately struck with the potential value of the event for the production of a painting of the historic scene, and the Tussaud brothers at once commissioned him to execute the work for them. Sir George thereupon communicated the idea to the Duke, who readily responded, and offered to give the necessary sittings. We have the sketches made by Hayter in preparation for the work, and among them appears a drawing of Joseph Tussaud himself, although he does not enter the actual picture. Hearing that the artist was making progress with the painting, the Duke visited his studio, and, having expressed himself warmly in appreciation of the picture (the figures had been but lightly limned in at the time), said: "Well, I suppose you'll want me to sit for my picture here?"

Hayter has given us a most characteristic portrait of Wellington as he then appeared. He is dressed in his usual blue frock-coat, white trousers, and white cravat, fastened with the familiar steel buckle. He stoops a little as was his wont, his head is lightly covered with snow-white hair, and his manly features are marked with an expression of mingled curiosity and sadness as, hat in hand, he looks upon the recumbent Napoleon. The picture was completed early in December, 1852, and has been on view in the Napoleon Rooms at the Exhibition ever since.

The engravings of the picture have been circulated in thousands throughout the world, and, strange to say, they are exceedingly popular in Austria. It is an interesting fact that the painting in question was the last portrait for which the Duke ever sat. When the Duke himself died, Madame Tussaud's advertised "A full length model of the Great Duke, taken from Life during his frequent visits to the Napoleon Relics."

Wellington himself would have been least surprised to learn that Madame Tussaud had added his likeness to her collection upon his death. Unfortunately, I've yet to find an engraving of the Duke's tableaux, but we do have the following description found in Our Young Folks: An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls, Volume 8 (1872) By John Townsend Trowbridge:

In a side room adjoining the long gallery lies the great Duke of Wellington in state. An awful feeling came over me, as if I were in the presence of the dead, as I looked upon that noble form, lying still and cold, with all the "pride of heraldry and pomp of power" around him, insensible alike to both. As he lay there on his tented couch of velvet and gold, it seemed as if that must be the "Great Duke," and not a waxen image only, that never lived nor spoke. Among the numerous portraits which adorn the walls is a very fine one of the duke visiting the relics of Napoleon, which are shown in another room.

Many a person has recorded his or her feelings about the Duke of Wellington's funeral carriage, above, a great monstrosity of a thing weighing 18 tons and made from the French guns taken in battle and designed by Prince Albert himself in a misguided attempt to pay a fitting tribute to the Duke. All agree that it was pretty much a hideous object. Charles Dickens wrote, "For form of ugliness, horrible combination of colour, hideous motion, and general failure, there never was such a work achieved as the Car." After the funeral, there was a general debate as to what to do with the thing. The question even made its way to Parliament, as mentioned in a book called Stray Papers, published in 1876 -

During a Parliamentary debate, Mr. Layard said, that there was a hideous piece of upholstery under cover opposite Marlborough House at the disposal of anybody who would take it; but, as nobody would take it, they were now asked to vote £840 for its removal to St. Paul's, where it would be placed beneath one of the crypts. He alluded to the car used at the funeral of the late Duke of Wellington, and that which nothing more hideous had ever been invented. The best thing would be to give it to Madame Tussaud, or, if she would not take it, to burn it.

The carriage now rests at Stratfield Saye. But, the same book goes on to tell us that:

Several years ago, a figure of the late Duke of Wellington stood under one of the skylights in the principal room (at Madame Tussaud's.) By some unaccountable oversight, the attendant omitted to draw the blinds on one occasion when shutting up for the night, and next morning the hot rays of a July sun fell on the Duke's countenance with such fervour that his Grace's nose began to run, and, by the time the doors were opened, had disappeared completely. So much of the figure being destroyed, restoration to its original form was found to be impossible.

There used to be a figure of the Duke of Wellington, and Napoleon, on display at Madame Tussaud's in London, but when I was there recently I didn't see it. Then again, the place was so crowded I might have missed it. It's good to think that the Duke is still around, even in storage, and might be brought out again soon.

Published on April 05, 2011 02:02

April 4, 2011

Style from Elizabeth I to Elizabeth II

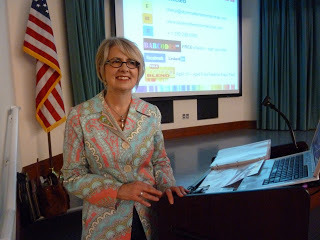

Victoria here, reporting on a delightful presentation I attended in Naples, FL, at the public library. Presenter Cheryl Lampard, who is a consultant on fashion, make-up and image, spoke on royal style to an eager group of mostly females who peppered her with questions at the end of her talk -- mostly about the upcoming royal wedding. What did she think the Queen would wear? What about the royal limousine, THE dress and so forth. I can reliably report that here in FL, the audience for the great event will be huge.

Victoria here, reporting on a delightful presentation I attended in Naples, FL, at the public library. Presenter Cheryl Lampard, who is a consultant on fashion, make-up and image, spoke on royal style to an eager group of mostly females who peppered her with questions at the end of her talk -- mostly about the upcoming royal wedding. What did she think the Queen would wear? What about the royal limousine, THE dress and so forth. I can reliably report that here in FL, the audience for the great event will be huge.Cheryl Lampard's business is Style Matters International, based in Naples. Click here for her website.

Ms. Lampard's power point talk began with a discussion of "Dress for Success" Elizabethan style. Ms. Lampard says, "Your image is your brand" and that applies to royalty as well as to the rest of us. Elizabeth I needed to project an image of power nobles to foreign diplomats to the great mass of her subjects. The luxury and splendor of her clothing represented the powers and strength of the nation over which she ruled.

Elizabeth I inherited her father's fine taste and flair for showmanship. The first Elizabethan Era is celebrated for its achievements, particularly in the arts, e.g. Shakespeare.

At left, Elizabeth I (1533-1603) as a girl, whose future was anything but assured. Nevertheless she outlasted her half-brother, Edward, and her half-sister Mary, to take the throne in 1558 at age 25. She ruled for 44 years, overcoming both internal threats (e.g. Protestants vs. Catholics) and external threats from continental powers.

At left, Elizabeth I (1533-1603) as a girl, whose future was anything but assured. Nevertheless she outlasted her half-brother, Edward, and her half-sister Mary, to take the throne in 1558 at age 25. She ruled for 44 years, overcoming both internal threats (e.g. Protestants vs. Catholics) and external threats from continental powers.In the painting, Tudor style prevailed in dress, jewelry, hair and make-up. As Ms. Lampard pointed out, nothing is new when it comes to fashion; we see cycles of clothing and make-up styles throughout history. A primary example: the wasp waist. Clothing emphasized the narrowness of the waist in contrast to the wide skirts and sleeves. As time went on, Elizabeth I's fashions exaggerated the small waist, as well as sumptuousness in fabric and decoration.

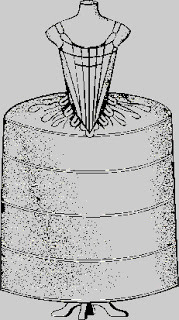

To emphasize the narrowness of the wasp waist, women wore a "stomacher," in the shape of a triangle across the chest and pointing down at the waist. Often richly decorated, the stomacher was a separate piece of clothing that was tied or otherwise fastened on and used with a variety of gowns.

A set of hoops called a farthingale spread out the skirt and widened the gown from hips to floor. Both the stomacher and farthingale were stiffened with wood, whalebone, ivory or mother-of-pearl.

In order for the skirt to fall in graceful folds, often it was necessary to use a bumroll below the waist.

The effect was obviously to make the waist look small in comparison to the hips, carrying the hourglass figure to extremes. Full sleeves and wide shoulders add to the illusion.

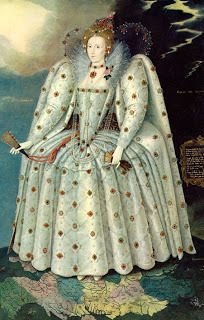

The Armada Portrait (at Woburn Abbey with other versions and/or copies elsewhere) shows Elizabeth I in a setting rich with important and impressive symbolism. The gown of expensive satins and silks is crusted with jewels, emphasizing the prosperity and magnificence of the court. Her hand rests on the globe, to portray England's dominance of the sea, and on either side of her head, two stages of the 1588 defeat of the Spanish Armada can be seen.

By late in Elizabeth I's reign, everything was exaggerated. The skirts were amazingly wide and heavy. The sleeves look like her arms would be nearly unmovable. The tall ruffs would make turning her head uncomfortable.

By late in Elizabeth I's reign, everything was exaggerated. The skirts were amazingly wide and heavy. The sleeves look like her arms would be nearly unmovable. The tall ruffs would make turning her head uncomfortable.The make-up, too, was dangerous. Pale skin was admired, signifying that the person never had to work in the outdoors. In another recurring fashion trend, this white make-up was lead- based well into the 19th century, poisonous to the system and causing pockmarks on the face. Fashion can be foolish indeed.

Ms. Lampard described many more details about Elizabethan fashions, the sleeves, the ruffs, (tall, starched, and probably scratchy), and the discomfort endured for the sake of image. She jokingly compared these fashions with today's exaggerated platform stiletto-heeled shoes.

Moving to the Victorian period, she discussed the return of the wasp waist, the continued need for the monarch to project an image of stability and power, and the adoption (forever and ever) of Victoria's white wedding gown as the standard for brides worldwide. Formerly, she said, silver had been the usual color for royal brides.

Victoria became the mother of nine children, then endured a long period of mourning after her husband's death. But she knew how to dress for the role of head of the empire.

Even in the 1880's Victoria kept up appearances. Below, a photograph of Queen Victoria

for her Diamond Jubilee in 1897.

Moving on to today's era, the second Elizabethan Age, we see again in the young Princess Elizabeth, the recurrence of the wasp waist, for her 1947 wedding gown and a few years later for her coronation in 1953.

Wedding gown, 1947, by Norman Hartnell

Wedding gown, 1947, by Norman Hartnell Coronation gown, 1953, by Norman HartnellAlthough the current Queen Elizabeth has not been in the forefront of fashion trends, she too has recognized her obligation to represent her nation in a modern way. For ceremonial events, of course, she is suitably gowned, crowned and bejeweled. For her day-to-day activities, Ms. Lampard said, she can be particularly admired for her choice of hats. Designing a hat that is flattering, attractive and capable of having the monarch's face visible is not an easy job.

Coronation gown, 1953, by Norman HartnellAlthough the current Queen Elizabeth has not been in the forefront of fashion trends, she too has recognized her obligation to represent her nation in a modern way. For ceremonial events, of course, she is suitably gowned, crowned and bejeweled. For her day-to-day activities, Ms. Lampard said, she can be particularly admired for her choice of hats. Designing a hat that is flattering, attractive and capable of having the monarch's face visible is not an easy job.Here are a few views of the Queen's headgear.

Here is a gallery from CBS News of Queen Elizabeth II's hats.

All in all we had a wonderful time last week covering centuries of royal fashion and chatting about the wedding to come. Many thanks, Cheryl Lampard of Style Matters International.

Published on April 04, 2011 02:00

April 3, 2011

The Birthday of Jane Digby el Mezrab

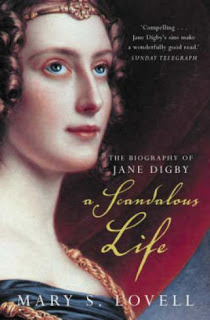

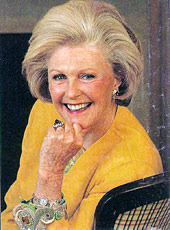

Today, in the midst of turbulent international events, we have a great deal of curiosity and concern about the middle east. So did the British of the 19th century, dealing as they did with the Ottoman Empire and its 600-year rule over a large part of the world. By the 19th century, its eventual disintegration was well underway…think of Byron fighting for Greek independence, for example. Though trade and commerce continued, the middle east was not an area familiar to most of 19th century Britain. The stories of intrepid women travelers who went there to live are particularly fascinating. Mary S. Lovell has written the story of our birthday girl's adventurous life, published in 1998, and titled in the U.S. Rebel Heart.

Today, in the midst of turbulent international events, we have a great deal of curiosity and concern about the middle east. So did the British of the 19th century, dealing as they did with the Ottoman Empire and its 600-year rule over a large part of the world. By the 19th century, its eventual disintegration was well underway…think of Byron fighting for Greek independence, for example. Though trade and commerce continued, the middle east was not an area familiar to most of 19th century Britain. The stories of intrepid women travelers who went there to live are particularly fascinating. Mary S. Lovell has written the story of our birthday girl's adventurous life, published in 1998, and titled in the U.S. Rebel Heart.  BBC Photo

BBC PhotoLovell is the author of many biographies: Bess of Hardwick, Beryl Markham, the Mitford Sisters, and Amelia Earhart. Her book about the Churchills will be released this month in the UK and in May in the US. For her website, click here.

Jane Elizabeth Digby, Lady Ellenborough (1807-1881), moved to Damascus in the early 1850's, following a path forged by Lady Hester Stanhope (1776-1839) after the death of her uncle, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger in 1805. Lady Hester's story will be forthcoming on this blog in the future. Jane Digby was exceptionally beautiful but apparently unlucky at finding enduring love for many years. She was raised in the wealthy and aristocratic household of her father, Admiral Sir Henry Digby, and her mother Mary Coke, daughter of the lst Earl of Leicester. Before she was 20 years old, Jane married Edward Law, second Baron Ellenborough, later the Earl of Ellenborough, who was Governor General of India 1842-44. Jane was Ellenborough's second wife and bore him (supposedly) one son who lived only two years. They were divorced in 1830, after undergoing the almost-impossible process of ending a marriage in those days, proving her adultery through several through several decisions of legal and ecclesiastical courts and culminating in an act of the House of Lords.

Jane Elizabeth Digby, Lady Ellenborough (1807-1881), moved to Damascus in the early 1850's, following a path forged by Lady Hester Stanhope (1776-1839) after the death of her uncle, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger in 1805. Lady Hester's story will be forthcoming on this blog in the future. Jane Digby was exceptionally beautiful but apparently unlucky at finding enduring love for many years. She was raised in the wealthy and aristocratic household of her father, Admiral Sir Henry Digby, and her mother Mary Coke, daughter of the lst Earl of Leicester. Before she was 20 years old, Jane married Edward Law, second Baron Ellenborough, later the Earl of Ellenborough, who was Governor General of India 1842-44. Jane was Ellenborough's second wife and bore him (supposedly) one son who lived only two years. They were divorced in 1830, after undergoing the almost-impossible process of ending a marriage in those days, proving her adultery through several through several decisions of legal and ecclesiastical courts and culminating in an act of the House of Lords.

1831 Painting of Jane Digby, Lady Ellenborough

1831 Painting of Jane Digby, Lady Ellenboroughby Joseph Karl Stieler

Jane had many affairs, often with very prominent men, including (but not limited to) King Ludwig I of Bavaria, King Otto of Greece (son of Ludwig), Austrian statesman Prince Schwarzenberg, and her cousin, George Anson. In all she married four times and had several children, most of whom died very young. Her daughter by Schwarzenberg was raised by the Prince's sister in Basel.

To follow the progress of her many affairs and marriages is like reading a scandalous travelogue She finally settled in Syria with her fourth husband, Sheikh Medjuel el Mezrab, who was two decades younger than she was. She wore Arab dress and spent part of each year living a nomadic life in the desert with her husband's tribe. In Damascus, they lived in an elegant villa and entertained many Europeans, including the famous traveler, explorer and author Richard Burton and his wife.

It is often noted in connection with Jane Digby that her great great grandniece was Pamela Churchill Harriman, nee Digby (1920-1997), U. S. Ambassador to France 1993-1997, whose life of romance with world statesmen could be considered a 20th century version of Jane's own story. Her three husbands were Randolph Churchill, Leland Hayward, and Averill Harriman.She was also linked in the popular press with many other prominent men, among them Edward R. Murrow, Prince Aly Khan, Baron Elie de Rothschild, William S. Paley, Gianni Agnelli, and Stavros Niarchos.

It is often noted in connection with Jane Digby that her great great grandniece was Pamela Churchill Harriman, nee Digby (1920-1997), U. S. Ambassador to France 1993-1997, whose life of romance with world statesmen could be considered a 20th century version of Jane's own story. Her three husbands were Randolph Churchill, Leland Hayward, and Averill Harriman.She was also linked in the popular press with many other prominent men, among them Edward R. Murrow, Prince Aly Khan, Baron Elie de Rothschild, William S. Paley, Gianni Agnelli, and Stavros Niarchos. Though we might, while wishing her happy birthday, call Jane Digby "one of a kind," but she obviously left a legacy to her descendants.

Published on April 03, 2011 02:00

April 2, 2011

Anecdotes of Sheridan from the Pen of Thomas Creevey

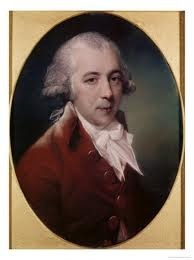

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

". . . Sheridan entered into whatever fun was going on at the Pavilion as if he had been a boy, tho' he was then 55 years of age. Upon one occasion he came into the drawing-room disguised as a police officer to take up the Dowager Lady Sefton for playing at some unlawful game; and at another time, when we had a phantasmagoria at the Pavilion, and were all shut up in perfect darkness, he continued to seat himself upon the lap of Madame Gerobtzoff [?], a haughty Russian dame, who made row enough for the whole town to hear her.

"The Prince, of course, was delighted with all this; but at last Sheridan made himself so ill with drinking, that he came to us soon after breakfast one day, saying he was in a perfect fever, desiring he might have some table beer, and declaring that he would spend that day with us, and send his excuses by Bloomfield for not dining at the Pavilion. I felt his pulse, and found it going tremendously, but instead of beer, we gave him some hot white wine, of which he drank a bottle, I remember, and his pulse subsided almost instantly. . . . After dinner that day he must have drunk at least a bottle and a half of wine. In the evening we were all going to the Pavilion, where there was to be a ball, and Sheridan said he would go home, i.e., to the Pavilion (where he slept) and would go quietly to bed. He desired me to tell the Prince, if he asked me after him, that he was far from well, and was gone to bed.

So when supper was served at the Pavilion about 12 o'clock, the Prince came up to me and said: "' What the devil have you done with Sheridan to-day, Creevey? I know he has been dining with you, and I have not seen him the whole day.'

"I said he was by no means well and had gone to bed; upon which the Prince laughed heartily, as if he thought it all fudge, and then, taking a bottle of claret and a glass, he put them both in my hands and said:"' Now Creevey, go to his bedside and tell him I'll drink a glass of wine with him, and if he refuses, I admit he must be damned bad indeed.'

"I would willingly have excused myself on the score of his being really ill, but the Prince would not believe a word of it, so go I must. When I entered Sheridan's bedroom, he was in bed, and, his great fine eyes being instantly fixed upon me, he said :— "' Come, I see this is some joke of the Prince, and I am not in a state for it.'

"I excused myself as well as I could, and as he would not touch the wine, I returned without pressing it, and the Prince seemed satisfied he must be ill.

"About two o'clock, however, the supper having been long over, and everybody engaged in dancing, who should I see standing at the door but Sheridan, powdered as white as snow, as smartly dressed as ever he could be from top to toe. . . . I joined him and expressed my infinite surprise at this freak of his. He said:"Will you go with me, my dear fellow, into the kitchen, and let me see if I can find a bit of supper.'

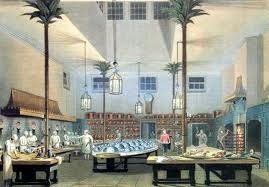

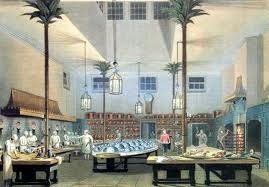

Kitchens at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton"Having arrived there, he began to play off his cajolery upon the servants, saying if he was the Prince they should have much better accommodation, etc, etc, so that he was surrounded by supper of all kinds, every one waiting upon him. He ate away and drank a bottle of claret in a minute, returned to the ballroom, and when I left it between three and four he was dancing.

Kitchens at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton"Having arrived there, he began to play off his cajolery upon the servants, saying if he was the Prince they should have much better accommodation, etc, etc, so that he was surrounded by supper of all kinds, every one waiting upon him. He ate away and drank a bottle of claret in a minute, returned to the ballroom, and when I left it between three and four he was dancing.

In the year 1810, Mrs. Creevey, her daughters and myself were spending our summer at Richmond. Sheridan and his wife (who was a relation and particular friend of Mrs. Creevey's) came down to dine and stay all night with us. There being no other person present after dinner, when the ladies had left the room, Sheridan said : "'A damned odd thing happened to me this morning, and Hester [Mrs. Sheridan] and I have agreed in coming down here to-day that no human being shall ever know of it as long as we live; so that nothing but my firm conviction that Hester is at this moment telling it to Mrs. Creevey could induce me to tell it to you.'

"Then he said that the money belonging to this office of his in the Duchy being always paid into Biddulph's or Cox's bank (I think it was) at Charing Cross, it was his habit to look in there. There was one particular clerk who seemed always so fond of him, and so proud of his acquaintance, that he every now and then cajoled him into advancing him £10 or £20 more than his account entitled him to. . . . That morning he thought his friend looked particularly smiling upon him, so he said:—

'"I looked in to see if you could let me have ten pounds.'

"'Ten pounds!' replied the clerk; 'to be 'sure I can, Mr. Sheridan. You've got my letter, sir, have you not?'

"' No,' said Sheridan, 'what letter?'

"It is literally true that at this time and for many, many years Sheridan never got twopenny-post letters,* because there was no money to pay for them, and the postman would not leave them without payment.

"'Why, don't you know what has happened, sir?' asked the clerk. 'There is £1200 paid into your account. There has been a very great fine paid for one of the Duchy estates, and this £1200 is your percentage as auditor.'

"Sheridan was, of course, very much set up with this £1200, and, on the very next day upon leaving us, he took a house at Barnes Terrace, where he spent all his £1200. At the end of two or three months at most, the tradespeople would no longer supply him without being paid, so he was obliged to remove. What made this folly the more striking was that Sheridan had occupied five or six different houses in this neighbourhood at different periods of his life, and on each occasion had been driven away literally by non-payment of his bills and consequent want of food for the house. Yet he was as full of his fun during these two months as ever he could be—gave dinners perpetually and was always on the road between lames and London, or Barnes and Oatlands (the Duke of York's), in a large job coach upon which he would have his family arms painted."

* The charge at this time for letters sent and delivered within the metropolitan district was only 2d., payable by the recipient; but country letters were charged from l0d. to 1s. 6d. and more, according to distance.

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Sheridan". . . Sheridan entered into whatever fun was going on at the Pavilion as if he had been a boy, tho' he was then 55 years of age. Upon one occasion he came into the drawing-room disguised as a police officer to take up the Dowager Lady Sefton for playing at some unlawful game; and at another time, when we had a phantasmagoria at the Pavilion, and were all shut up in perfect darkness, he continued to seat himself upon the lap of Madame Gerobtzoff [?], a haughty Russian dame, who made row enough for the whole town to hear her.

"The Prince, of course, was delighted with all this; but at last Sheridan made himself so ill with drinking, that he came to us soon after breakfast one day, saying he was in a perfect fever, desiring he might have some table beer, and declaring that he would spend that day with us, and send his excuses by Bloomfield for not dining at the Pavilion. I felt his pulse, and found it going tremendously, but instead of beer, we gave him some hot white wine, of which he drank a bottle, I remember, and his pulse subsided almost instantly. . . . After dinner that day he must have drunk at least a bottle and a half of wine. In the evening we were all going to the Pavilion, where there was to be a ball, and Sheridan said he would go home, i.e., to the Pavilion (where he slept) and would go quietly to bed. He desired me to tell the Prince, if he asked me after him, that he was far from well, and was gone to bed.

So when supper was served at the Pavilion about 12 o'clock, the Prince came up to me and said: "' What the devil have you done with Sheridan to-day, Creevey? I know he has been dining with you, and I have not seen him the whole day.'

"I said he was by no means well and had gone to bed; upon which the Prince laughed heartily, as if he thought it all fudge, and then, taking a bottle of claret and a glass, he put them both in my hands and said:"' Now Creevey, go to his bedside and tell him I'll drink a glass of wine with him, and if he refuses, I admit he must be damned bad indeed.'

"I would willingly have excused myself on the score of his being really ill, but the Prince would not believe a word of it, so go I must. When I entered Sheridan's bedroom, he was in bed, and, his great fine eyes being instantly fixed upon me, he said :— "' Come, I see this is some joke of the Prince, and I am not in a state for it.'

"I excused myself as well as I could, and as he would not touch the wine, I returned without pressing it, and the Prince seemed satisfied he must be ill.

"About two o'clock, however, the supper having been long over, and everybody engaged in dancing, who should I see standing at the door but Sheridan, powdered as white as snow, as smartly dressed as ever he could be from top to toe. . . . I joined him and expressed my infinite surprise at this freak of his. He said:"Will you go with me, my dear fellow, into the kitchen, and let me see if I can find a bit of supper.'

Kitchens at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton"Having arrived there, he began to play off his cajolery upon the servants, saying if he was the Prince they should have much better accommodation, etc, etc, so that he was surrounded by supper of all kinds, every one waiting upon him. He ate away and drank a bottle of claret in a minute, returned to the ballroom, and when I left it between three and four he was dancing.

Kitchens at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton"Having arrived there, he began to play off his cajolery upon the servants, saying if he was the Prince they should have much better accommodation, etc, etc, so that he was surrounded by supper of all kinds, every one waiting upon him. He ate away and drank a bottle of claret in a minute, returned to the ballroom, and when I left it between three and four he was dancing.

In the year 1810, Mrs. Creevey, her daughters and myself were spending our summer at Richmond. Sheridan and his wife (who was a relation and particular friend of Mrs. Creevey's) came down to dine and stay all night with us. There being no other person present after dinner, when the ladies had left the room, Sheridan said : "'A damned odd thing happened to me this morning, and Hester [Mrs. Sheridan] and I have agreed in coming down here to-day that no human being shall ever know of it as long as we live; so that nothing but my firm conviction that Hester is at this moment telling it to Mrs. Creevey could induce me to tell it to you.'

"Then he said that the money belonging to this office of his in the Duchy being always paid into Biddulph's or Cox's bank (I think it was) at Charing Cross, it was his habit to look in there. There was one particular clerk who seemed always so fond of him, and so proud of his acquaintance, that he every now and then cajoled him into advancing him £10 or £20 more than his account entitled him to. . . . That morning he thought his friend looked particularly smiling upon him, so he said:—

'"I looked in to see if you could let me have ten pounds.'

"'Ten pounds!' replied the clerk; 'to be 'sure I can, Mr. Sheridan. You've got my letter, sir, have you not?'

"' No,' said Sheridan, 'what letter?'

"It is literally true that at this time and for many, many years Sheridan never got twopenny-post letters,* because there was no money to pay for them, and the postman would not leave them without payment.

"'Why, don't you know what has happened, sir?' asked the clerk. 'There is £1200 paid into your account. There has been a very great fine paid for one of the Duchy estates, and this £1200 is your percentage as auditor.'

"Sheridan was, of course, very much set up with this £1200, and, on the very next day upon leaving us, he took a house at Barnes Terrace, where he spent all his £1200. At the end of two or three months at most, the tradespeople would no longer supply him without being paid, so he was obliged to remove. What made this folly the more striking was that Sheridan had occupied five or six different houses in this neighbourhood at different periods of his life, and on each occasion had been driven away literally by non-payment of his bills and consequent want of food for the house. Yet he was as full of his fun during these two months as ever he could be—gave dinners perpetually and was always on the road between lames and London, or Barnes and Oatlands (the Duke of York's), in a large job coach upon which he would have his family arms painted."

* The charge at this time for letters sent and delivered within the metropolitan district was only 2d., payable by the recipient; but country letters were charged from l0d. to 1s. 6d. and more, according to distance.

Published on April 02, 2011 00:57

April 1, 2011

The Creevey Papers

Thomas Creevey

Thomas CreeveyI am a firm believer in using primary sources when doing research, my personal favorite resource being diaries and letters of the day. Prince Puckler Muskau, Princess Lieven, Horace Walpole, Lady Shelley, etc., etc., etc. all have a place on my shelf and I re-read them frequently. I will be posting blogs consisting of various amusing passages from these letters, beginning tomorrow with Creevey's anecdotes of Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Therefore, I thought that an introduction to both Creevey and his Papers were in order, had you not met them before.

Thomas Creevey was born in Liverpool in 1768, the son of a merchant sea captain who transported slaves. It has been suggested, though never proven, that Creevey was natural son of Lord Molyneux, later first Earl of Sefton, He studied at Queens' College, Cambridge, and then trained as a lawyer. In 1802, Creevey met and married Eleanor Ord, daughter of Charles Brandling, MP, widow of William Ord, who had six children and a private income - very handy for a man who never earned much on his own. The couple, by all accounts, were very happily married, with Creevey regarding all the Ord children as his own. Also in 1802, thanks to his uncle, Creevey became a Whig MP in the House of Commons. In 1806, the Prime Minister, Lord Grenville, appointed Creevey as Secretary to the Board of Control, but he lost the job when Grenville resigned the following year. After unsuccessfully fighting against the development of the railways, and supporting Lord Grey and his plans for parliamentary reform, Creevey lost his seat, as a result of those reforms. Grey made him Treasurer of the Ordnance in 1830, and then Lord Melbourne made him treasurer of Greenwich Hospital. From 1818 on, after his wife died, Creevey was a rather poor man, although he remained popular. He is mostly remembered because his writings, including intermittent diary extracts, were published in 1903, under the title of 'The Creevey Papers'. The book is considered important because of Creevey's gossipy, almost Pepysian, insights into many of the main characters of the period.

From the Greville Memoirs

February 20th. (1838)—I made no allusion to the death of Creevey at the time it took place, about a fortnight ago, having said something about him elsewhere. Since that period he had got into a more settled way of life. He was appointed to one of the Ordnance offices by Lord Grey, and subsequently by Lord Melbourne to the Treasurer ship of Greenwich Hospital, with a salary of 600l. a year and a house. As he died very suddenly, and none of his connexions were at hand, Lord Sefton sent to his lodgings and (in conjunction with Vizard, the solicitor) caused all his papers to be sealed up. It was found that he had left a woman who had lived with him for four years as his mistress, his sole executrix and residuary legatee, and she accordingly became entitled to all his personalty (the value of which was very small, not more than 300/. or 400l.) and to all the papers which he left behind him. These last are exceedingly valuable, for he had kept a copious diary for thirty-six years, had preserved all his own and Mrs. Creevey's letters, and copies or originals of a vast miscellaneous correspondence. The only person who is acquainted with the contents of these papers is his daughter-in-law, whom he had frequently employed to copy papers for him, and she knows how much there is of delicate and interesting matter, the publication of which would be painful and embarrassing to many people now alive, and make very inconvenient and premature revelations upon private and confidential matters. ... Then there is Creevey's own correspondence with various people, especially with Brougham, which evidently contains things Brougham is anxious to suppress, for he has taken pains to prevent the papers from falling into the hands of any person likely to publish them, and has urged Vizard to get possession of them either by persuasion, or purchase, or both. In point of fact they are now in Vizard's hands, and it is intended by him and Brougham, probably with the concurrence of others, to buy them of Creevey's mistress, though who is to become the owner of the documents, or what the stipulated price, and what their contemplated destination, I do not know. The most extraordinary part of the affair is, that the woman has behaved with the utmost delicacy and propriety, has shown no mercenary disposition, but expressed her desire to be guided by the wishes and opinions of Creevey's friends and connexions, and to concur in whatever measures may be thought best by them with reference to the character of Creevey, and the interests and feelings of those who might be affected by the conents of the papers. Here is a strange situation in which to find a rectitude of conduct, a moral sentiment, a grateful and disinterested liberality which would do honour to the highest birth, the most careful cultivation, and the strictest principle. It would be a hundred to one against any individual in the ordinary rank of society and of average good character acting with such entire absence of selfishness, and I cannot help being struck with the contrast between the motives and disposition of those who want to get hold of these papers, and of this poor woman who is ready to give them up. They, well knowing that, in the present thirst for the sort of information Creevey's journals and correspondence contain, a very large sum might be obtained for them, are endeavouring to drive the best bargain they can with her for their own particular ends, while she puts her whole confidence in them, and only wants to do what they tell her she ought to do under the circumstances of the case.

More of Thomas Creevey tomorrow!

Published on April 01, 2011 01:01

March 31, 2011

The Windsor Dioramas by Guest Blogger Hester Davenport

A few years ago in Sebastopol in the Crimea I walked around a compelling recreation of a moment in the siege of the city during the Crimean war where the closest figures are almost life-size. This kind of model is called a diorama. In Windsor Museum we have our own diorama of a siege but ours in on a small scale, as are the others which pinpoint moments in the town's history. They're like miniature theatres, in glass-fronted cases and lit from above, all of them lively and dramatic, where you almost expects the tiny figures to continue the actions they've just begun.

Part of a diorama showing the barons attacking Windsor Castle in 1216

Part of a diorama showing the barons attacking Windsor Castle in 1216 © Windsor Museum

The Windsor dioramas were commissioned in the 1950s from two friends, Judith Ackland and Mary Stella Edwards. They had met when at Regent Street Polytechnic in 1919, where they studied art, and afterwards they set up a home and studio together in a cottage called The Cabin, on the beautiful North Devon coast.

The Cabin at Bucks Mills

The Cabin at Bucks Mills appledorearts.org

For many years they spent the summers travelling, painting landscapes and selling their art, but after the Second World War, perhaps feeling they were too old for gipsy living, they started a new career making dioramas. After meticulous research into their subjects Mary painted the backgrounds, while Judith made the figures. She developed her own way of modelling figures which she called 'Jackanda,' using wire and compressed cotton-wool. Remarkably she could not only position her figures in a life-like way, but even on a miniature scale – each figure measures around 10 cms – she could create expression and in the case of historical characters recognisable portraits.

Judith Ackland at work by Mary Stella Edwards

Judith Ackland at work by Mary Stella Edwards Bucksmillscabin.blogspot.com

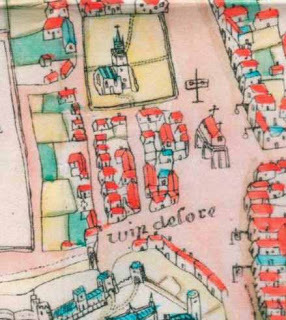

The Windsor commissions came about after one of their dioramas was shown in the Guildhall as part of a Florence Nightingale centenary exhibition. The enlightened local council then asked the women to create a diorama for 1957, which would mark 350 years since John Norden's map of Windsor in 1607.

Detail of John Norden's 1607 map of Windsor

It was the first map of the town and shows the recently-built Market Hall (1596), with the old parish church behind. You can also see the pillory where wrong-doers were punished by being forced to stand pinioned by their neck and wrists, enduring cat-calls and, if unlucky, well-aimed fruit and vegetables (our Museum has a model pillory for visitors to stick their heads in, and a basket of fruit and veg., luckily fluffy, for friends and relations to throw).

Windsor Market-place in 1607 © Windsor Museum

The women peopled their market scene with imagination: a pig has made a bid for freedom, overturning a stall. Vegetables cascade across the ground and a plucked chicken lies with its feet in the air. There are other stalls, a group of women churning butter and behind them a butcher's shop. An elderly man in a fur-edged robe, oblivious to the mayhem, must be someone important, perhaps the Mayor. A well-dressed woman with her page pulls her skirts out of the way.

Every detail has been researched, even to the type of coach seen in the background. One of the clever aspects of these dioramas is the way three-dimensional modelling merges with two-dimensional figures and landscape without any sharp division.

So successful was this scene that the women were asked to make another, and the following year they produced Windsor Bridge in the year 1770, again carefully researched.

Windsor Bridge in 1770

It's a windy day, washing is blowing on a line and the women crossing the bridge have to hang on to their hats. An artist sitting at the corner sketching is recognisably Paul Sandby, who painted many Windsor scenes including the bridge.

Paul Sandby sketching by Watkins William Winnmuseumwales.ac.uk

The river is imagined running across the front of the diorama, and a boy is fishing in it. Masts of the barges which carried goods up and down the river can be seen, and bargees with their horses which hauled the boats along. Above looms the Castle, as it was in 1770, when the Round Tower was short and squat.

A year on and the women produced their most ambitious work: the Golden Jubilee celebrations of George III in Bachelors' Acre in 1809, 150 years after the event.

On 25 October, when George III entered the 50th year of his reign, rejoicing was nationwide. In Windsor the so-called Bachelors of Windsor organised an ox-roast on the Acre – the name of this piece of open ground is thought to come from a time when butts were set up there for young men to practice their archery. Unfortunately the King, in his 71st year, lame, deaf and of poor sight, was too infirm to attend, but at one o'clock Queen Charlotte arrived on the arm of her second son, Frederick Duke of York, with most of her other children in tow (the Prince of Wales was also absent as he shunned public appearances because of his unpopularity over his treatment of his wife Caroline of Brunswick). The Mayor is in his robes, with the Corporation all dressed in blue with white wands of office. Even the cook had been given a blue smock and white silk stockings.

All the figures were researched from portraits in the Royal Collection. Princess Augusta is on the left in yellow, plump Princess Elizabeth is in blue, with the Duke of Kent, Queen Victoria's father behind her, Princess Sophia is in pink with the really bad sheep of the family, the swaggering Ernest Duke of Cumberland at her side in uniform (he was believed to harbour incestuous thoughts about his sister Sophia and less than a year later suspected of killing his valet.) The Duke of Sussex is behind him. The royal party graciously partook of slices of the meat served on silver dishes, before retiring to the garden at the back for a 'cold collation.'

Unfortunately because of its complexity and the illness of one of the women, the Jubilee diorama was late in delivery and over-budget. So for the next one, the Council laid down strict rules, and consequently it is the least detailed.

It shows the siege of Windsor Castle in 1216. After King John had failed to keep to the terms of Magna Carta (1215), the furious barons invited Prince Louis of France to take the English throne. Much of southern England fell into their hands, but Windsor Castle held out and after three months the attackers withdrew (they should have waited as King John died not long afterwards).

Once more, the Castle, the armour and weapons of war were meticulously researched. (It's a pity you can't see the horses behind the tents in the photo.) This is the diorama on show at the new Museum at the moment and the other three will take their turns. There are dressing-up clothes of the period for children, and one little boy was proud to have spotted the man who is collapsing with an arrow fired from the Castle walls in his neck.

Note the men lighting a bonfire against the Castle walls to weaken them.

Judith and Mary made other dioramas for Windsor, though they are simpler in scope, including one not in a case and with only three figures, which celebrates the Bayeux Tapestry.

Judith Ackland died in Devon in 1971. Thereafter Mary Stella Edwards organised exhibitions of her friend's work and moved to what had been her family home in Staines, not far from Windsor, where she died in 1989. (The Cabin was kept as it was, and is now part-owned by the National Trust.) It had been a remarkable partnership and one we are proud to display in our Museum.

Mary Stella Edwards by Judith Ackland

Mary Stella Edwards and Judith Ackland[image error]

Published on March 31, 2011 00:25

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.