Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 154

March 30, 2011

In Memoriam

Published on March 30, 2011 01:02

The Darker Side of 19th Century London - The Great Stink - Part Two

In additionn to saltpetre men, night soil men removed human waste that they then sold as fertilizer for crops. It was filthy job that involved crawling through cesspits and sewers or descending into them from ladders. Henry Mayhew describes them in his London Labour and the London Poor. You can read it here.

By 1810, the city's one million inhabitants had to be content with 200,000 cesspits. The pressure on these and the haphazard sewer system caused the pits to overflow into street drains designed originally to cope with rainwater, but now also used to carry waste from factories, slaughterhouses and other activities, contaminating the city before emptying into the River Thames, or into the old London streams - the Fleet, the Wandle, the West Bourne, the Ravensbourne, the New, the Holbourne and many others that had been partially covered. WC's discharged human waste directly into these streams and as most of those on the south side were tide-locked and drained into the Thames only at low tide, the results were catastrophic - much of London's drinking water was still being extracted from the Thames, often downstream from the sewage discharge points.

Whilst the government and various commissioners and officials put forth plans for cleaning up London's cesspits and sewers, the Duke of Wellington forged ahead with action of his own at the Tower of London - he was Constable of the Tower for 26 years. Centuries before, latrines and been built and desgined to empty directly into the moat set into the outer wall of Edward I's Brass Mount in the north-eastern corner of the Tower. In addition, the moat connected to the River Thames, which washed its foul and putrid self about the Tower at both high and low tide. In 1830, the Duke of Wellington ordered the silt from the moat be taken to fertilize market gardens at Battersea, but this was not enough to prevent complaints in 1841 that the banks exposed at low tide were 'impregnated with putrid animal and excrementitious matter … emitting a most prejudicial smell,' resulting in 80 men from the garrison being taken to hospital. Wellington ordered the moat to be completely drained and covered over, the work being completed in 1845.

Dire problems with London's water supply inevitably took their toll on the City's inhabitants - cholera first struck London in 1832 and again in 1840. In 1854 London physician Dr John Snow discovered that the disease was transmitted by drinking water contaminated by sewage after an epidemic broke out in Soho, but this idea was not widely accepted even by that late date.

The lawyer Edwin Chadwick, secretary to the Poor Law Commision, was one of many to draw attention to London's unsanitary living conditions. In 1842, he produced an uncompromising and influential paper, 'The Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain.' Shocked by the squalor of the slums, he cited 'atmospheric impurities produced by decomposing animal and vegetable substances,' 'damp and filth,' and 'close and overcrowded dwellings" as leading inevitably to disease and epidemics. Chadwick enlisted the aid of Charles Dickens, who personally recorded graphic accounts of the terrible state of reeking graveyards from his brother-in-law, Henry Austin, a leading sanitary reformer.

However, attempts at sanitary clean up were slow, as this letter to the editor of The Times - written in 1849 - shows -

TO THE EDITUR OF THE TIMES PAPER

Sur, -May we beg and beeseech your protection your proteckshion and power. We are Sur, as it may be, livin in a Wilderniss, so far as the rest of London knows anything of us, or as the rich and great people care about. We live in muck and filthe. We aint got no privies, no dust bins, no drains, no water splies, and no drain or suer in the hole place. The Suer Company in Greek Street, Soho Square, all great rich and powerful men, take no notice watsotnedever of our complaints. The Stenche of a Gully-hole is disgustin. We all of us suffur, and numbers are ill, and if the Colera comes Lord help us...

Teusday, Juley 3, 1849".

Nearly a decade later, the situation had hardly improved. The year 1858 saw an exceptionally hot summer, over the course of which the Thames and many of its urban tributaries continued to overflow with sewage. Bacteria grew and the miasma of noxious smells increased until even the members of the House of Commons couldn't ignore it, being driven out of the House by the foul odours.A House of Commons select committee was appointed to report on the Stink and recommend solutions and within 18 days a bill was passed into law that provided the funds necessary for a comprehensive sewer scheme for London, and to build the Embankment along the Thames in order to improve both the flow of water and of traffic.

1855 by the Metropolitan Board of Works which, after rejecting many schemes for "merciful abatement of the epidemic that ravaged the Metropolis", accepted a scheme to implement sewers proposed in 1859 by its chief engineer, Joseph Bazalgette. The intention of this very expensive scheme was to resolve the epidemic of cholera by eliminating the stench which was believed to cause it.

Massive sewers were built running along the north and south banks of the river Thames. These captured the waste that would otherwise pour into the river. The sewers gently inclined downwards to the east, resulting in the waste flowing towards the sea. In areas such as Victoria, the muddy foreshore was reclaimed, and sewers and the new underground railway were installed. On the surface, a 30 metre width of landscaped road and pavement was established, providing a modern and elegant boulevard now known as the Embankment, which also served to guard against flooding. These new sewers terminated at pumping stations east of London in Kent and Essex, where the waste was carried out to sea on the outgoing tide. The Prince of Wales opened the pumping station at Crossness in Kent in 1865.

Work on London's massive new sewer system continued over the next six years and, eventually the "Great Stink" became but a thing of memory, as did cholera.

The End

Published on March 30, 2011 00:59

March 29, 2011

The Darker Side of 19th Century London - The Great Stink - Part One

Ah, falling in love - isn't it grand? You meet that someone special and in the space of a few moments the whole world changes. It's as though the entire planet tilted just the tiniest bit on its axis and now affords you a whole new look at the world. Being in love colours the things we see and tints everything in a new light. We are dazzled, bewitched and God seems in his heaven. All is right with the world! It's the same with our love affair with historic Britiain.

If you were introduced to British history through fiction, your love affair with the 19th century might include visions of

a damsel who needs saving

a damsel who needs saving

gorgeous gowns

gorgeous gowns

and dashing heroes

and dashing heroes

Or perhaps you discovered British history through film or television. In that case, chances are that your visions of England include such images as these:

An outdoor tea party in Cranford

An outdoor tea party in Cranford

glittering Regency interiors

glittering Regency interiors

or a cheeky Royal friend

or a cheeky Royal friend

Once your interest in the 19th century has been piqued, you may be compelled to do further research into the period when, inevitably, you'll discover the darker side of London history. Reader, it stank. Literally. Not romantic or genteel in the least. And enough so that books, both fiction and non, have been written about the condition.

And Thames Water even made a film about it, which you can watch here. The Great Stink took place in London in 1858, but of course London had been stinking for centuries prior. In the first half of the 19th Century, London's population was 2.5 million, all of whom ultimately discharged their waste directly onto the streets or into the Thames. Besides people, there were hundreds of thousands of horses, cows, dogs, cats, sheep, etc. adding their daily contributions to the waste problem.

John Cadbury, social reformer and candy company founder, wrote: "Foul odors emanated from more than 200,000 cesspools across London, in alleyways, yards, even the basements of houses. It was not a smell that could be easily washed away."

Most homes and businesses were built above cesspits, designed to drain to the street by means of a crudely built culvert to a partially open sewer trench in the center of the street. The design was faulty, to say the least. Cesspits often overflowed and waste soaked foundations, walls and floors of living quarters. Culverts typically became blocked and caused sewage to spread under buildings and contaminate shallow wells, cisterns and water ways from which drinking water was drawn. In October 1660, Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary: "Going down to my cellar...I put my feet into a great heap of turds, by which I find that Mr. Turner's house of office is full and comes into my cellar."

While causing disgust in Pepys and thousands of other Londoners, cesspits gave work to a portion of the population who included night soil men and saltpetre men. Saltpetre is another name for potassium nitrate, an essential ingredient in the manufacture of gunpowder. It was typically generated by collecting vegetable and animal waste into heaps and mixing it with limestone, mortar, earth and ashes. These heaps were kept moist from time to time with urine or other waste from stables. Digging for ingredients in outbuildings such as dovecotes and stables provided adequate supplies of gunpowder for the navy. Beginning during the reign of Elizabeth I, official saltpetre men were given powers to requisition any suitable deposits they came across.

In 1621 James I appointed Lords of the Admiralty as Commissioners for Saltpetre and Gunpowder. They divided the country into districts for collection, and specialised saltpetre men were appointed and given weekly quotas to meet. They were also awarded powers with the right to enter premises to dig for nitrogenous earth.

In addition, an Ordinace was passed in October 1643 entitled `The Ordinance to provide Salt-petre for making Gunpowder' Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660, and reads in part " . . . it is held most necessary, that the digging of Salt-petre and the making of Gunpowder shall by all fit Means be encouraged at this Time, when it so much concerns the Public Safety: Nevertheless, to prevent the reviving of those Oppressions and Vexations exercised upon the People, under the colourable Authority of Commissions granted to Salt-petre-men, which Burthen hath been eased since the Sitting of this Parliament, and to the End that there may not be any Pretence to interrupt the Work, it is Ordained, by the Lords and Commons in Parliament, That such Persons as shall be nominated and allowed by the said Lords and Commons in Parliament shall have Power and Authority, by this present Ordinance, to search and dig for Salt-petre, in all Pigeon-houses, Stables, and all other Out-houses, Yards, and Places likely to afford that Earth, at fit seasons and Hours, between Sun-rising and Sun-setting (except all Dwelling-houses, Shops, and Milkhouses) . . . "

Part Two Tomorrow!

If you were introduced to British history through fiction, your love affair with the 19th century might include visions of

a damsel who needs saving

a damsel who needs saving

gorgeous gowns

gorgeous gowns  and dashing heroes

and dashing heroesOr perhaps you discovered British history through film or television. In that case, chances are that your visions of England include such images as these:

An outdoor tea party in Cranford

An outdoor tea party in Cranford  glittering Regency interiors

glittering Regency interiors

or a cheeky Royal friend

or a cheeky Royal friend Once your interest in the 19th century has been piqued, you may be compelled to do further research into the period when, inevitably, you'll discover the darker side of London history. Reader, it stank. Literally. Not romantic or genteel in the least. And enough so that books, both fiction and non, have been written about the condition.

And Thames Water even made a film about it, which you can watch here. The Great Stink took place in London in 1858, but of course London had been stinking for centuries prior. In the first half of the 19th Century, London's population was 2.5 million, all of whom ultimately discharged their waste directly onto the streets or into the Thames. Besides people, there were hundreds of thousands of horses, cows, dogs, cats, sheep, etc. adding their daily contributions to the waste problem.

John Cadbury, social reformer and candy company founder, wrote: "Foul odors emanated from more than 200,000 cesspools across London, in alleyways, yards, even the basements of houses. It was not a smell that could be easily washed away."

Most homes and businesses were built above cesspits, designed to drain to the street by means of a crudely built culvert to a partially open sewer trench in the center of the street. The design was faulty, to say the least. Cesspits often overflowed and waste soaked foundations, walls and floors of living quarters. Culverts typically became blocked and caused sewage to spread under buildings and contaminate shallow wells, cisterns and water ways from which drinking water was drawn. In October 1660, Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary: "Going down to my cellar...I put my feet into a great heap of turds, by which I find that Mr. Turner's house of office is full and comes into my cellar."

While causing disgust in Pepys and thousands of other Londoners, cesspits gave work to a portion of the population who included night soil men and saltpetre men. Saltpetre is another name for potassium nitrate, an essential ingredient in the manufacture of gunpowder. It was typically generated by collecting vegetable and animal waste into heaps and mixing it with limestone, mortar, earth and ashes. These heaps were kept moist from time to time with urine or other waste from stables. Digging for ingredients in outbuildings such as dovecotes and stables provided adequate supplies of gunpowder for the navy. Beginning during the reign of Elizabeth I, official saltpetre men were given powers to requisition any suitable deposits they came across.

In 1621 James I appointed Lords of the Admiralty as Commissioners for Saltpetre and Gunpowder. They divided the country into districts for collection, and specialised saltpetre men were appointed and given weekly quotas to meet. They were also awarded powers with the right to enter premises to dig for nitrogenous earth.

In addition, an Ordinace was passed in October 1643 entitled `The Ordinance to provide Salt-petre for making Gunpowder' Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660, and reads in part " . . . it is held most necessary, that the digging of Salt-petre and the making of Gunpowder shall by all fit Means be encouraged at this Time, when it so much concerns the Public Safety: Nevertheless, to prevent the reviving of those Oppressions and Vexations exercised upon the People, under the colourable Authority of Commissions granted to Salt-petre-men, which Burthen hath been eased since the Sitting of this Parliament, and to the End that there may not be any Pretence to interrupt the Work, it is Ordained, by the Lords and Commons in Parliament, That such Persons as shall be nominated and allowed by the said Lords and Commons in Parliament shall have Power and Authority, by this present Ordinance, to search and dig for Salt-petre, in all Pigeon-houses, Stables, and all other Out-houses, Yards, and Places likely to afford that Earth, at fit seasons and Hours, between Sun-rising and Sun-setting (except all Dwelling-houses, Shops, and Milkhouses) . . . "

Part Two Tomorrow!

Published on March 29, 2011 01:13

March 28, 2011

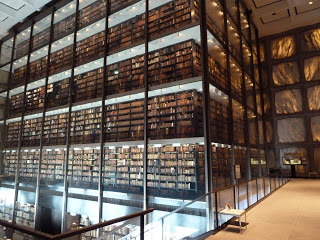

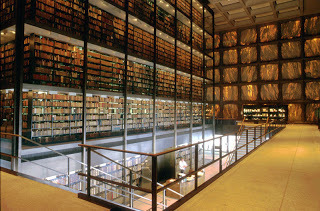

Yale's Beinecke Rare Book Library

On March 4, 2011, I visited the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library on the Yale University campus with Diane Gaston and her kind DH who drove us up from Washington, D. C. I have written several times in the last month about our visit to the exhibition Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power and Brilliance at the Yale Center for British Art. We didn't have time for a lot more on our visit to New Haven, CT, but we did take a turn around the very fascinating Beinecke Rare Book Library, just a few blocks from the YCBA. Jim Perkins snapped this of the two intrepid researchers on our way across campus.

On March 4, 2011, I visited the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library on the Yale University campus with Diane Gaston and her kind DH who drove us up from Washington, D. C. I have written several times in the last month about our visit to the exhibition Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power and Brilliance at the Yale Center for British Art. We didn't have time for a lot more on our visit to New Haven, CT, but we did take a turn around the very fascinating Beinecke Rare Book Library, just a few blocks from the YCBA. Jim Perkins snapped this of the two intrepid researchers on our way across campus. The Yale campus is renowned for its Gothic architecture, such as this tower, but it also has many modern buildings, some of which are truly masterpieces of contemporary architecture by some of the world's leading practitioners. The neo-Gothic buildings are quite beautiful if hardly practical in today's technological age.

The Yale campus is renowned for its Gothic architecture, such as this tower, but it also has many modern buildings, some of which are truly masterpieces of contemporary architecture by some of the world's leading practitioners. The neo-Gothic buildings are quite beautiful if hardly practical in today's technological age.  Peeking through this elaborate gate, one could expect to see dedicated students and brilliant professors in the same rarefied atmosphere of the greatest universities -- it almost could be Cambridge or Oxford's dreaming spires. Alas, we did not have time to investigate and any students we saw were either hurrying along with their phones to their ears -- or practicing jumps on their skateboards.

Peeking through this elaborate gate, one could expect to see dedicated students and brilliant professors in the same rarefied atmosphere of the greatest universities -- it almost could be Cambridge or Oxford's dreaming spires. Alas, we did not have time to investigate and any students we saw were either hurrying along with their phones to their ears -- or practicing jumps on their skateboards.  Nevertheless, we were a bit disappointed when we came upon the Beinecke's building. While the proportions were good, it looked rather bland, a grid upon a white surface without embellishment. It was designed by Gordon Bunshaft (1909-1990), of Skidmore Owings and Merrill, a student of the 20th century's greatest architects such as Mies van der Rohe. Bunshaft also designed Lever House, on NYC's Park Avenue, the Hirshhorn Museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D. C., and other iconic buildings. But we quickly changed our opinions when we entered this magnificent structure.

Nevertheless, we were a bit disappointed when we came upon the Beinecke's building. While the proportions were good, it looked rather bland, a grid upon a white surface without embellishment. It was designed by Gordon Bunshaft (1909-1990), of Skidmore Owings and Merrill, a student of the 20th century's greatest architects such as Mies van der Rohe. Bunshaft also designed Lever House, on NYC's Park Avenue, the Hirshhorn Museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D. C., and other iconic buildings. But we quickly changed our opinions when we entered this magnificent structure. In my photograph, you can see the glass-enclosed collection displayed in all its glory. On the right, you see some of the sections of translucent marble that bring the filtered sunlight inside. The effect is breathtaking. I will include a better photo from their website (link below). Around the outside of the glass-wrapped stacks is exhibition space, occupied by several treasures -- a copy of Audubon's Birds of America -- and a Gutenberg Bible. Other than the first picture below, the photos are mine. I love a museum that allows photos -- why not, I always wonder when there are restrictions on cameras without flashes.

In my photograph, you can see the glass-enclosed collection displayed in all its glory. On the right, you see some of the sections of translucent marble that bring the filtered sunlight inside. The effect is breathtaking. I will include a better photo from their website (link below). Around the outside of the glass-wrapped stacks is exhibition space, occupied by several treasures -- a copy of Audubon's Birds of America -- and a Gutenberg Bible. Other than the first picture below, the photos are mine. I love a museum that allows photos -- why not, I always wonder when there are restrictions on cameras without flashes.

Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, completed 1963

Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, completed 1963It is said that this treatment of glass enclosed books was the inspiration for the British Library's glass tower of George III's collection in their new building of 1997.

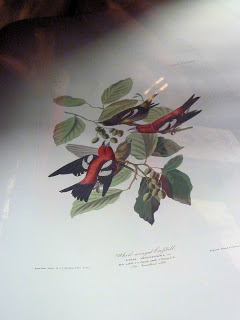

Among of the Beinecke' treasures are two sets of The Birds of America, the works of John James Audubon (1785-1851). Audubon was born in Haiti and came to the US in 1803. For more than ten years he drew and painted American birds. According to the text panel, each book contained 425 plates showing 1055 birds, mostly drawn from life. To the left is the page showing the white-winged Crossbill. The plates were engraved and hand colored ion Edinburgh and London; the books were sold by subscription.

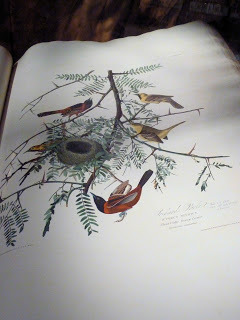

Among of the Beinecke' treasures are two sets of The Birds of America, the works of John James Audubon (1785-1851). Audubon was born in Haiti and came to the US in 1803. For more than ten years he drew and painted American birds. According to the text panel, each book contained 425 plates showing 1055 birds, mostly drawn from life. To the left is the page showing the white-winged Crossbill. The plates were engraved and hand colored ion Edinburgh and London; the books were sold by subscription.  To the right is Audubon's Orchard Oriole in one of the two volumes of The Birds of America in Yale's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The building was a gift of the Beinecke family in 1963; it is one of the world's largest buildings devoted to the preservation of rare books and manuscripts. In addition to the visible stacks, there are several floors underground for archived of precious books and papers.

To the right is Audubon's Orchard Oriole in one of the two volumes of The Birds of America in Yale's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The building was a gift of the Beinecke family in 1963; it is one of the world's largest buildings devoted to the preservation of rare books and manuscripts. In addition to the visible stacks, there are several floors underground for archived of precious books and papers. Collections range from medieval and renaissance manuscripts to papers relating to the life, family and careers of a wide range of persons, from Boswell to "Walt Whitman to Langston Hughes. I am looking forward to attending the next meeting of the Angela Thirkell Society, which will be held at the Beinecke. How Ms. Thirkell's papers ended up at Yale will be an interesting topic!

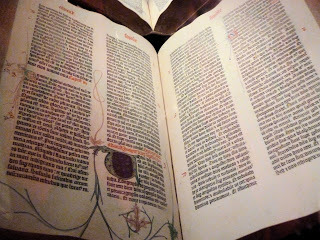

Every day a page is turned in the Beinecke's Gutenberg Bible, one of five complete Gutenbergs in the U.S. To the left is the page we saw, not too elaborate, but certainly an interesting design. Johann Gutenberg of Mainz, Germany, printed these Bibles about 1455, the world's first books printed with moveable type. There are 21 complete Gutenberg Bibles in the world and another 20+ incomplete versions. This copy, once in the Benedictine Abbey in Melk, Austria, was purchased by Mrs. Edward S. Harkness for presentation to Yale as a memorial for Mrs. Stephen V. Harkness.

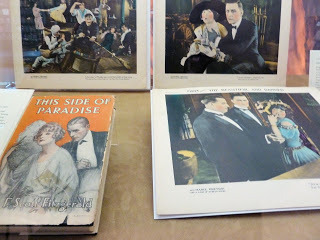

Every day a page is turned in the Beinecke's Gutenberg Bible, one of five complete Gutenbergs in the U.S. To the left is the page we saw, not too elaborate, but certainly an interesting design. Johann Gutenberg of Mainz, Germany, printed these Bibles about 1455, the world's first books printed with moveable type. There are 21 complete Gutenberg Bibles in the world and another 20+ incomplete versions. This copy, once in the Benedictine Abbey in Melk, Austria, was purchased by Mrs. Edward S. Harkness for presentation to Yale as a memorial for Mrs. Stephen V. Harkness. At right is one of the many displays around the Beinecke Library as part of an exhibition called Psyche and Muse, shown until June 13, 2011. According to the brochure, it "explores cultural, clinical and scientific discourse on human psychology and its influend on twentieth-century writers, artists, and thinkers." I am sure that F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda and their friends provided rich source material for the exhibition's essays. Diane and I could have spent hours investigating each display and panel. However, another visit to Thomas Lawrence beckoned and we had to pass up a close examination.

At right is one of the many displays around the Beinecke Library as part of an exhibition called Psyche and Muse, shown until June 13, 2011. According to the brochure, it "explores cultural, clinical and scientific discourse on human psychology and its influend on twentieth-century writers, artists, and thinkers." I am sure that F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda and their friends provided rich source material for the exhibition's essays. Diane and I could have spent hours investigating each display and panel. However, another visit to Thomas Lawrence beckoned and we had to pass up a close examination. Here is link to the Beinecke's website.

For more information about Psyche and Muse, start here.

Published on March 28, 2011 02:00

March 27, 2011

Blair Castle to be Sold by Savills

Copyright Francis Frith Blair Castle, one of Scotland's oldest continuously occupied estates, is for sale through Savills. Set in 1,500 acres near Dalry, Ayrshire, it has been the home of the Blair family since 1105. The current owner, Luke Borwick, a descendant of the founding family, endeavored - a la Monarch of the Glen - to maintain the estate with golfing weekends, weddings, advertising shoots and other commercial activities. During its long history, Mary Queen of Scots, William Wallace and Robert the Bruce have enjoyed hospitality at the castle, which is now to be sold along with its contents.

Copyright Francis Frith Blair Castle, one of Scotland's oldest continuously occupied estates, is for sale through Savills. Set in 1,500 acres near Dalry, Ayrshire, it has been the home of the Blair family since 1105. The current owner, Luke Borwick, a descendant of the founding family, endeavored - a la Monarch of the Glen - to maintain the estate with golfing weekends, weddings, advertising shoots and other commercial activities. During its long history, Mary Queen of Scots, William Wallace and Robert the Bruce have enjoyed hospitality at the castle, which is now to be sold along with its contents.

In addition to the 16 bedroom house, the 670 acre grounds include 12 cottages, salmon fishing and woodlands. From the Savills listing description: "Blairquhan Castle lies at the heart of the estate, overlooking the Water of Girvan which flows for over 3½ miles along the northern boundary of the estate. It is rare to find an estate which affords such privacy. About 670 acres in all, the estate also has 12 further estate properties, a walled garden with glasshouse, ice house, outstanding woodlands, farmland, a Purdey Award winning low ground shoot, roe stalking, trout fishing, and salmon and sea trout fishing. Lord Cockburn, writing as he worked his way around the South Circuit of the Scottish Bench in September 1844, wrote about his stay at Blairquhan: `I rose early…and surveyed the beauties of Blairquhan. It deserves its usual praises. A most gentleman-like place rich in all sorts of attractions – of wood, lawn, river, gardens, hill, agriculture and pasture.'"

Also from the Savills site: "Approached by way of three drives, the principal route to the Castle, the three mile Long Approach, starts at the Ayr Lodge and runs alongside the Water of Girvan. The castle is first glimpsed through the trees on the approach. A key characteristic of the castle is the extent to which it has

been preserved as William Burn and Sir David Hunter Blair completed it in 1824. Certain improvements were warranted, since the castle had only one bathroom on the principal floor when it was originally built, with accommodation for 18 resident indoor servants. An ambitious refurbishment in 1970 won the Saltire Award and was followed by an ingenious conversion by the architect Michael Laird, which made use of the former servants' rooms to provide a modern Estate Office.

"There are now 16 bedrooms and 12 bathrooms and a driver's overnight room. The castle has been extremely well maintained, with work including significant roof repairs, re-leading the main tower, and installation of new central heating boilers. Laid out over three floors, the accommodation is as shown in the accompanying photographs and on the layout plans. In all, there are over 70 rooms. Reception rooms include a saloon, two drawing rooms, a library and a dining room. In addition there are three kitchens, a library, a billiard room, picture galleries, a table tennis room, museums, stores and wine cellars."

Whilst bits of British history hit the selling block daily, some as large or larger than Blair Castle, it's always heart rending to read of these individual properties, their owners and their history. One can only hope that whomever purchases the Estate will preserve it to the same standards the family strove to achieve.

You will find more pictures and info about the Estate, it's lodgings, gardens and history here. And all the sale details from property agent Savills website here. To read more about recently saved Scottish castles, click here.

Copyright Francis Frith Blair Castle, one of Scotland's oldest continuously occupied estates, is for sale through Savills. Set in 1,500 acres near Dalry, Ayrshire, it has been the home of the Blair family since 1105. The current owner, Luke Borwick, a descendant of the founding family, endeavored - a la Monarch of the Glen - to maintain the estate with golfing weekends, weddings, advertising shoots and other commercial activities. During its long history, Mary Queen of Scots, William Wallace and Robert the Bruce have enjoyed hospitality at the castle, which is now to be sold along with its contents.

Copyright Francis Frith Blair Castle, one of Scotland's oldest continuously occupied estates, is for sale through Savills. Set in 1,500 acres near Dalry, Ayrshire, it has been the home of the Blair family since 1105. The current owner, Luke Borwick, a descendant of the founding family, endeavored - a la Monarch of the Glen - to maintain the estate with golfing weekends, weddings, advertising shoots and other commercial activities. During its long history, Mary Queen of Scots, William Wallace and Robert the Bruce have enjoyed hospitality at the castle, which is now to be sold along with its contents. In addition to the 16 bedroom house, the 670 acre grounds include 12 cottages, salmon fishing and woodlands. From the Savills listing description: "Blairquhan Castle lies at the heart of the estate, overlooking the Water of Girvan which flows for over 3½ miles along the northern boundary of the estate. It is rare to find an estate which affords such privacy. About 670 acres in all, the estate also has 12 further estate properties, a walled garden with glasshouse, ice house, outstanding woodlands, farmland, a Purdey Award winning low ground shoot, roe stalking, trout fishing, and salmon and sea trout fishing. Lord Cockburn, writing as he worked his way around the South Circuit of the Scottish Bench in September 1844, wrote about his stay at Blairquhan: `I rose early…and surveyed the beauties of Blairquhan. It deserves its usual praises. A most gentleman-like place rich in all sorts of attractions – of wood, lawn, river, gardens, hill, agriculture and pasture.'"

Also from the Savills site: "Approached by way of three drives, the principal route to the Castle, the three mile Long Approach, starts at the Ayr Lodge and runs alongside the Water of Girvan. The castle is first glimpsed through the trees on the approach. A key characteristic of the castle is the extent to which it has

been preserved as William Burn and Sir David Hunter Blair completed it in 1824. Certain improvements were warranted, since the castle had only one bathroom on the principal floor when it was originally built, with accommodation for 18 resident indoor servants. An ambitious refurbishment in 1970 won the Saltire Award and was followed by an ingenious conversion by the architect Michael Laird, which made use of the former servants' rooms to provide a modern Estate Office.

"There are now 16 bedrooms and 12 bathrooms and a driver's overnight room. The castle has been extremely well maintained, with work including significant roof repairs, re-leading the main tower, and installation of new central heating boilers. Laid out over three floors, the accommodation is as shown in the accompanying photographs and on the layout plans. In all, there are over 70 rooms. Reception rooms include a saloon, two drawing rooms, a library and a dining room. In addition there are three kitchens, a library, a billiard room, picture galleries, a table tennis room, museums, stores and wine cellars."

Whilst bits of British history hit the selling block daily, some as large or larger than Blair Castle, it's always heart rending to read of these individual properties, their owners and their history. One can only hope that whomever purchases the Estate will preserve it to the same standards the family strove to achieve.

You will find more pictures and info about the Estate, it's lodgings, gardens and history here. And all the sale details from property agent Savills website here. To read more about recently saved Scottish castles, click here.

Published on March 27, 2011 00:23

March 25, 2011

Osterley Park, An Adam Jewel

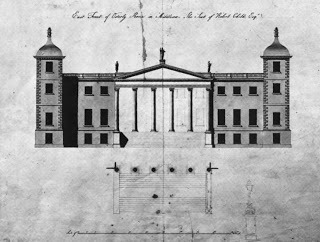

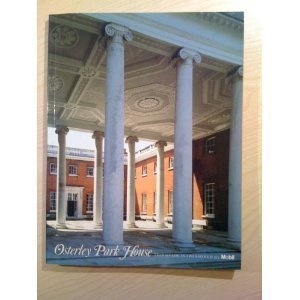

Osterley Park was once a rural retreat but today it is in Greater London, reachable by the tube (look for the Osterley stop on the Piccadilly line). The original Tudor mansion was built in 1575 by Sir Thomas Gresham, banker and founder of the Royal Exchange. The old house was built of red brick around a square courtyard. After considerable alterations in the 17th century, it was acquired by Francis Child, the immensely wealthy London banker, in 1713. His grandson Francis hired Robert Adam to transform the house in 1761 but he died before the house was finished, leaving the house to his brother Robert Child.

Osterley Park was once a rural retreat but today it is in Greater London, reachable by the tube (look for the Osterley stop on the Piccadilly line). The original Tudor mansion was built in 1575 by Sir Thomas Gresham, banker and founder of the Royal Exchange. The old house was built of red brick around a square courtyard. After considerable alterations in the 17th century, it was acquired by Francis Child, the immensely wealthy London banker, in 1713. His grandson Francis hired Robert Adam to transform the house in 1761 but he died before the house was finished, leaving the house to his brother Robert Child. Adam's work was completed in 1780. The center of the west section of the building was removed by Adam and replaced with a giant white Ionic portico.

Adam's work was completed in 1780. The center of the west section of the building was removed by Adam and replaced with a giant white Ionic portico..

The elegant portico opens up the courtyard.

The Tudor caps on the corners were left in place.

The Tudor caps on the corners were left in place.In many ways, the remodeling is quite similar to the work done on Syon House (see the post of Jan. 16, 2011), which is not very far away, also in the London borough of Hounslow, once in the countryside but now suburban London.

The 5th Earl of Jersey (1773-1859) became the owner by way of his marriage to Robert Child's granddaughter, Sarah Sophia Fane, the Lady Jersey who was a patroness of Almack's. The story of the young heiress is well known, the second elopement of a Child female.

The 5th Earl of Jersey (1773-1859) became the owner by way of his marriage to Robert Child's granddaughter, Sarah Sophia Fane, the Lady Jersey who was a patroness of Almack's. The story of the young heiress is well known, the second elopement of a Child female.Robert Child's daughter (Sarah Anne Child) had eloped with John Fane, later 10th Earl of Westmorland, in 1782. Robert Child (1739-82), proud of being a prince of the merchant class and not an aristocrat, did not want his property and fortune to go to the Westmorland family. He wrote a will which left his money and property to the second child of his daughter.

Sarah Sophia Fane inherited everything at age eight. In 1804, she married George Villiers, who changed his name (a necessity under Child's will) to Child-Villiers and in time became the 5th Earl of Jersey. He was the son of that Countess of Jersey who was a mistress of the Prince Regent. For more details on the Ladies Jersey, see our post of 4/2/10.

The Osterley house was rarely used by the Jerseys, who had his country estate Middleton in Oxfordshire in addition to a large townhouse in Berkeley Square. For decades Osterley was maintained but empty of life. The Jerseys entertained there once in a while. Eventually it was let to Sarah's cousin, Grace Caroline, dowager Duchess of Cleveland, a daughter of the 9th Earl of Westmorland. When she died, the 7th Earl of Jersey and his wife Margaret (1849-1945) lived and entertained there. The Lesson of the Master, a novella by Henry James, is set at Osterley.

The Osterley house was rarely used by the Jerseys, who had his country estate Middleton in Oxfordshire in addition to a large townhouse in Berkeley Square. For decades Osterley was maintained but empty of life. The Jerseys entertained there once in a while. Eventually it was let to Sarah's cousin, Grace Caroline, dowager Duchess of Cleveland, a daughter of the 9th Earl of Westmorland. When she died, the 7th Earl of Jersey and his wife Margaret (1849-1945) lived and entertained there. The Lesson of the Master, a novella by Henry James, is set at Osterley.

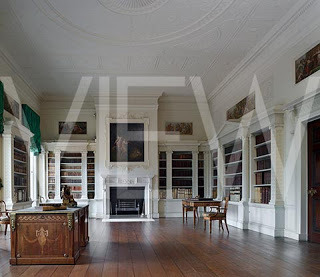

In 1885, the famous library was sold for thirteen thousand pounds. After the 7th earl died in 1915, the tenancy of the house foundered again. For many years, it was rarely used until the 9th earl opened it to the public on weekends. He gave it to the National Trust in 1949 and considerable restoration has taken place. It was recently used for some scenes in the film Gulliver's Travels and has been in numerous other movies and television productions.

The rooms are arranged in a horseshoe, with the entrance hall at the top. After walking through the great white portico, one crosses the courtyard and enters the magnificent hall designed by Adam in 1767. The color scheme is neutral, greys and whites with stucco panels of ancient military scenes on the walls. The floor has a black pattern on white marble, a reflection of the plasterwork ceiling design.

The rooms are arranged in a horseshoe, with the entrance hall at the top. After walking through the great white portico, one crosses the courtyard and enters the magnificent hall designed by Adam in 1767. The color scheme is neutral, greys and whites with stucco panels of ancient military scenes on the walls. The floor has a black pattern on white marble, a reflection of the plasterwork ceiling design. An apse at one end of the Hall, holds neo-classic statues, copies of ancient originals.

An apse at one end of the Hall, holds neo-classic statues, copies of ancient originals. National Trust PhotoThe Breakfast Room has a lovely view of the park and was used as a sitting room, graced by Adam's arched pier glasses. This room was redone in the 19th century, but the colors and some furniture is to Adam's design. The drawing for this design is in Sir John Soane's museum, London, as are many Adam designs. It is dated 24 April 1777. The room also contains a harpsichord of 1781, made by Jacob Kirckman and his nephew Abraham, who were well known for their instruments. It belonged to Sarah Sophia's mother, the countess of Westmorland. After her death in 1793, her husband asked to have it sent to him as a memento of his wife; it was returned to Osterley in 1805.

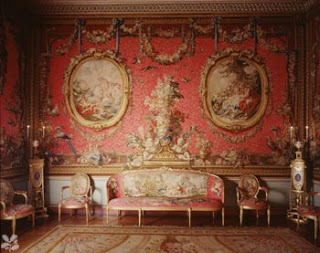

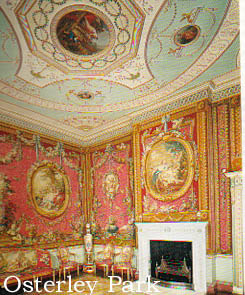

National Trust PhotoThe Breakfast Room has a lovely view of the park and was used as a sitting room, graced by Adam's arched pier glasses. This room was redone in the 19th century, but the colors and some furniture is to Adam's design. The drawing for this design is in Sir John Soane's museum, London, as are many Adam designs. It is dated 24 April 1777. The room also contains a harpsichord of 1781, made by Jacob Kirckman and his nephew Abraham, who were well known for their instruments. It belonged to Sarah Sophia's mother, the countess of Westmorland. After her death in 1793, her husband asked to have it sent to him as a memento of his wife; it was returned to Osterley in 1805.  The Tapestry Room was designed to hold a set of magnificent Gobelins tapestries designed by Francois Boucher depicting the Loves of the Gods. Several Adam rooms for other clients were decorated similarly, with the tapestries ordered from the Gobelins factory in Paris, which was run in the 1770's by a Scot. The sofa and eight matching armchairs were specially created and upholstered to match the tapestries.

The Tapestry Room was designed to hold a set of magnificent Gobelins tapestries designed by Francois Boucher depicting the Loves of the Gods. Several Adam rooms for other clients were decorated similarly, with the tapestries ordered from the Gobelins factory in Paris, which was run in the 1770's by a Scot. The sofa and eight matching armchairs were specially created and upholstered to match the tapestries.

The magnificent ceiling is another Adam masterpiece. The central medallion shows Minerva accepting the dedication of a child. The four smaller medallions show female representations of the liberal arts. As was the usual practice, these paintings were done on paper, affixed to canvas backing and placed in stucco frames after the ceiling was painted.

The magnificent ceiling is another Adam masterpiece. The central medallion shows Minerva accepting the dedication of a child. The four smaller medallions show female representations of the liberal arts. As was the usual practice, these paintings were done on paper, affixed to canvas backing and placed in stucco frames after the ceiling was painted. At left, a self portrait by Angelica Kauffman. She did many paintings for Adam, often in her well-known allegorical style. In an era when most of the artists were men, Kauffman (1741-1807) excelled at portraiture and even huge historical and allegorical paintings. Born in Switzerland, she found great success in England. In 1781, she married her colleague Antonio Zucchi (1726-95) and the couple went to live in Rome. Adam had met Zucchi in Rome and persuaded him to come to England in 1766. Zucchi also executed many paintings for Adam rooms, often in ceiling medallions or above doors and fireplaces.

At left, a self portrait by Angelica Kauffman. She did many paintings for Adam, often in her well-known allegorical style. In an era when most of the artists were men, Kauffman (1741-1807) excelled at portraiture and even huge historical and allegorical paintings. Born in Switzerland, she found great success in England. In 1781, she married her colleague Antonio Zucchi (1726-95) and the couple went to live in Rome. Adam had met Zucchi in Rome and persuaded him to come to England in 1766. Zucchi also executed many paintings for Adam rooms, often in ceiling medallions or above doors and fireplaces. In the State Bedchamber stands a huge bed, made to the Adam's design in 1776. The drawing is also in the Soane museum. Not only did Adam design the bed, he designed the hangings and embroidered silk counterpane and the interior of the dome. Included in the design are many allegorical symbols, including marigolds, the emblem of Child's Bank. In this room is another of the exquisite ceilings by Kauffman.

In the State Bedchamber stands a huge bed, made to the Adam's design in 1776. The drawing is also in the Soane museum. Not only did Adam design the bed, he designed the hangings and embroidered silk counterpane and the interior of the dome. Included in the design are many allegorical symbols, including marigolds, the emblem of Child's Bank. In this room is another of the exquisite ceilings by Kauffman.

The Etruscan Room Dressing Room shows Adam utilizing ancient designs discovered in Italy. At that time, the term Etruscan referred to the types of designs found on Greek vases. Horace Walpole in 1778 said the room was "painted all over like Wedgwood's ware, with black and yellow small grotesques." The furniture is attributed to Chippendale.

The Etruscan Room Dressing Room shows Adam utilizing ancient designs discovered in Italy. At that time, the term Etruscan referred to the types of designs found on Greek vases. Horace Walpole in 1778 said the room was "painted all over like Wedgwood's ware, with black and yellow small grotesques." The furniture is attributed to Chippendale.

Another view of the Etruscan Room at Osterley Park.

The Childs had spent a great deal of time developing the gardens and the park with lakes, wildernesses and open space. Fortunately, these also survive and have been restored. Under the supervision of the National Trust, the park is open to the public and is well used by hikers, strollers, bicyclists and bird watchers. As in most National Trust properties, there is an excellent gift shop

The Childs had spent a great deal of time developing the gardens and the park with lakes, wildernesses and open space. Fortunately, these also survive and have been restored. Under the supervision of the National Trust, the park is open to the public and is well used by hikers, strollers, bicyclists and bird watchers. As in most National Trust properties, there is an excellent gift shop and a tearoom serving delightful luncheons. Click here for more official information. As I have written before, the National Trust is an amazing organization; if you live in the U.S., you can support it by joining the Royal Oak Foundation (click here) which not only gives you access free to all NT properties in Britian and copies of their publications, but also brings you invitations to lectures and seminars by British historians, authors, gardeners, and art experts in major U.S. cities.

Published on March 25, 2011 02:00

March 24, 2011

A Visit to Postman's Park by Guest Blogger Jo Manning

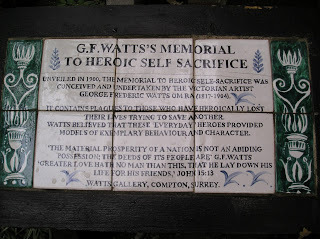

Postman's Park today, showing the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice aka The Wall of Heroes under the thatched awning.

I first heard about Postman's Park from my friend and colleague Hester Davenport, the biographer of Fanny Burney and Mary Robinson. She suggested it as someplace different and educational to take my London grandchildren. And, different, it truly is.

This tiny park, a blot of fastidiously landscaped green, elevated above the surrounding streets and tucked out of the way behind high buildings, is named for the site of the former General Post Office. Though only a few streets from St. Paul's Cathedral, getting there is not so easily accomplished; it behooves one to refer to a map.

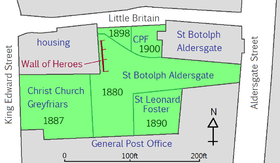

Starting at St. Paul's, orient yourselves with this map showing the cross streets…

As can be seen from this map, it was the site of several former burial grounds connected to a number of churches. In 1898, however, this quiet spot was incorporated as a park, becoming a place for "postmen," i.e., postal office employees, to take breaks and to eat their lunches.

In 1900, the painter George Frederic Watts selected the location to become a memorial to the altruistic among us, the ordinary, average people who died giving their lives for others. He would name this the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice, or the Wall of Heroes. These heroes were individuals who would otherwise never have been remembered, their deaths never commemorated; they were ordinary people, not famous. Watts was a celebrated artist of the Victorian period, a painter, portraitist, and sculptor often called the last great Victorian artist. In fact, the most recent biography of Watts, by Veronica Franklin Gould (who's also working on a biography of his second wife Mary Seton Watts), has this very same title.

The cover painting is from a self-portrait…

Over and above his artistic talent – often described as "titanic" -- he was an active and zealous advocate of social change who believed art could promote such change and make life better for all. From a working class family himself, he was interested in the elevation and recognition of the often-unheralded common man.

Another view of the Wall of Heroes

To celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria, he wrote a letter in 1887 to The Times proposing "to record the names of these likely to be forgotten heroes." He felt it would "make London richer by a work that is beautiful, and our nation richer by a record that is infinitely honourable." He concluded, "The material prosperity of a nation is not an abiding possession; the deeds of its people are."

A place for quiet contemplation at the end of the day…

Watts was serious and persistent in pursuing his concept of recording the stories of heroes in everyday life. He envisioned a kind of covered walkway against a marble wall that would be inscribed with the names of these people. His first idea was to build it in Hyde Park, but that didn't work out. He began to spend a great deal of his time – and even considered selling his homes and other properties– to finance this project.

This says it all…in Watts's own words and those of the Apostle John…put up by his widow…

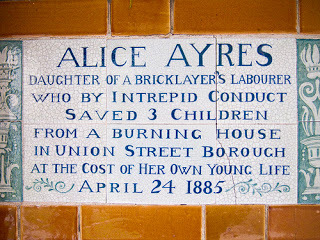

One of the first: the brave young girl Alice Ayres's memorial tablet, designed by William De Morgan and installed in 1902.

Postman's Park in the City of London area known as Little Britain became home to Watts's concept. He visualized and began to design a wall that would be set with ornate ceramic tablets dedicated to the memory of men, women, and children who'd given their lives for others. It evolved into kind of a loggia overhung with a thatched awning; 120 memorial tablets would be set into this protected wall. The tiles were commissioned from the prominent and renowned ceramicist William De Morgan.

This shows the arrangement of the older and newer tiles set together on the Wall…

Although it could easily be interpreted as yet another example of cloying and excessive Victorian sentimentality, the Memorial works because it is so much more than mere sentimentality. It is a very real and moving place. Who among us could remain unmoved whilst reading these solemn tiles?

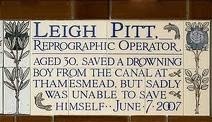

Sadly unable to save himself…Leigh Pitt's memorial is the latest to be added. You can read a full article on the service here.

This wall of tiles certainly moved my grandchildren, one of whom – the eldest -- walked it once, carefully reading the memorial tiles, and then walked it again, paying even closer attention to the text. Another grandchild, though, chastised me, saying it was too sad, and why had I taken them there? The stories of these deeds made her cry. Well, they made me cry, too.

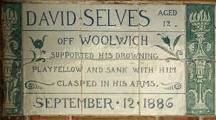

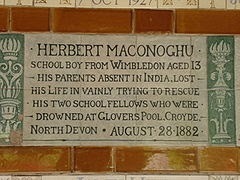

Aged just 12, he could not abandon his drowning friend…

They are really heartbreaking. The plight of these Victorian children and young adults, for most of them are very young… Trampled by horses, drowned, burned to death…not pretty. But that there are those who would put their lives at great risk to attempt to save others…well, that was…heartwarming…though immeasurably, heartbreakingly sad.

Trying to save a child from a runaway horse, she died of injuries received…

It does give one faith, does it not, in the goodness of others, to know that there are those individuals who give not a thought for themselves when the lives of others are at risk? In this country, in the last century, I am reminded of the 9/11 first responders, many of whom died (or have suffered life-threatening illnesses) in their selfless efforts to save their fellow man. It is extremely touching, this notion of self-sacrifice. How many of us would do this?

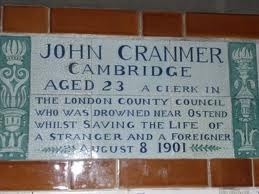

A Stranger AND A Foreigner! This one made us pause…what a statement!

When the park was opened, only four of the projected 120 tiles in place; a further nine were added during G.F. Watts's lifetime. Mary Seton Watts oversaw the installation of thirty-five more tablets after Watts's death in 1904, but as the building of the Watts Gallery and Chapel in Compton began to take more and more of her time, she lost interest in managing the project. (It was further complicated by a falling-out with the new tile manufacturer she'd engaged.)

A mere five more tiles were added during her lifetime – she died in 1938 – and the last tile in seventy-eight years was only added in 2009, by the Diocese of London. (See the end of this article for more about the Watts Gallery.)

Another drowning…

After this sobering look at Victorian self-sacrifice, we celebrated death with a greater appreciation for life. My grand-daughter Zoe jumped at least 2 ½ feet over a stone tablet; we all ate –and enjoyed -- ice cream cones. Life, thank goodness, goes on and children play.

My exuberant grand-daughter letting off some steam after going through the Wall twice…

Here we are walking through Postman's Park eating ice cream cones; the overcast day threatened rain, quite in keeping with the subdued nature of this unusual site…

George Frederic Watts died in 1904, not having fully realized his dream of the wall in Postman's Park. There were spaces for more tiles, but he was now into his late 80s, not at all well, and it had become more expensive to carry on the work. Though he'd maintained a file of unused clippings on other individuals whom he felt deserved a place on the wall, when he passed away at the age of 87, leaving his widow in charge, the impetus to continue the project faded away.

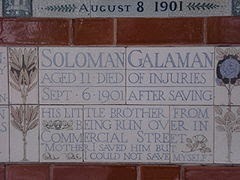

I saved him but I could not save myself…

It's remarkable, however, that we have what we do have at Postman's Park. It's a lasting legacy to a great man who wanted to celebrate the goodness of the common man, woman, and child in a beautiful and unforgettable way. The Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice was Grade II listed in 1972, to better preserve it for posterity.

George Frederic Watts, Victorian artist, social philosopher, at work…

Those of you who are particularly astute might recognize some scenes from a movie of a few years back, Closer, based on a play by Patrick Marber, which take place in Postman's Park. Key scenes between two of the characters – played by Natalie Portman and Jude Law -- took place here, generating a new interest in the site as a result. The full name of the enigmatic Natalie Portman character, the young stripper Alice -- Anna Friel had the role in the stage production – was, by the way, Alice Ayres. Alice the stripper took her name from the tile in the park, the name of the brave girl who lost her life saving three children from a burning building.

Before the play and the film, most Londoners had never heard of Postman's Park. But, the day we were there, it was fairly well populated by people sitting on the benches who appeared to be locals, and two tour groups came by, one group on bikes who hailed from Denmark. The word has obviously gotten around!

Portrait of Mary Seton Watts by her husband George Frederic Watts; she was his second wife. His first wife was the actress Ellen Terry, who was married to him for only one year when she was 16 and he was 47. (The marriage was dissolved.) Mary Watts, who married G.F. when he was 69 and she was 36, outlived him by 34 years…

First wife Ellen Terry… G.F. Watts's portrait of her is named Choosing…

Although a bit off the beaten path for tourists and locals, Postman's Park is well worth a visit, as are the Watts Gallery and Chapel, at Compton, near Guildford. (Take British Rail to Guildford.) This memorial to G.F. Watts – the glorious decorated chapel was designed by his artist wife, Mary Seton Watts – has been undergoing renovation/restoration and is slated to re-open in the summer of 2011.

Go to http://www.wattsgallery.org.uk/ for more on this remarkable man, his life, his times, his art, and his social and religious beliefs.

Published on March 24, 2011 00:43

March 23, 2011

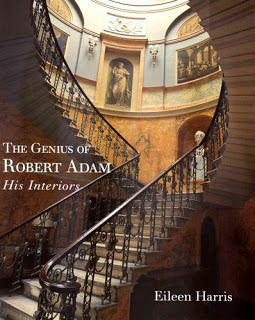

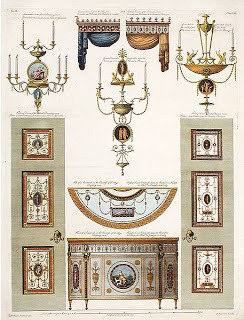

Robert Adam, Designer for the Ages

Victoria here, recently home from an antique show in 2011 Naples, Florida -- where there was a great deal of attention to the designs of an 18th century Scotsman, the renowned Robert Adam. I stopped counting how many tables, chairs, commodes, candlesticks and more were labeled "in the style of Adam." More than 200 years after he lived, Adam's designs are the standard by which all others are measured.

Victoria here, recently home from an antique show in 2011 Naples, Florida -- where there was a great deal of attention to the designs of an 18th century Scotsman, the renowned Robert Adam. I stopped counting how many tables, chairs, commodes, candlesticks and more were labeled "in the style of Adam." More than 200 years after he lived, Adam's designs are the standard by which all others are measured.We've had many posts on Adam houses here (3/29/10, 3/31/10,4/3/10,6/5/10, 1/16/11) and there will be more soon.

Robert Adam (1728-92) and his brother James (1730-1794) both gained prominence as architects, though it is Robert who has the more brilliant reputation. Today, Adam style is popular and instantly recognizable, whether in a fireplace, a chair or decorative arts.

Robert Adam (1728-92) and his brother James (1730-1794) both gained prominence as architects, though it is Robert who has the more brilliant reputation. Today, Adam style is popular and instantly recognizable, whether in a fireplace, a chair or decorative arts.Sons of William Adam, a leading architect in Edinburgh, the Adam Brothers were contemporaries of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Sir Thomas Gainsborough, Capability Brown, the great landscape designer, and Thomas Chippendale, whose furniture graces many Adam designs. Adam and his brothers worked in their father's business and also attended school in Edinburgh. The elder Adam was not only an architect; he was a man of learning and his home was the scene of conversations among some of the leading intellectuals of his day such as Adam Smith, Alexander Carlyle, and David Hume. This atmosphere influenced his

sons as they grew up.

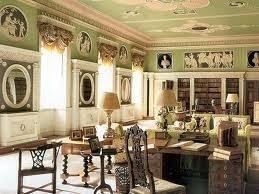

The library at Mellerstain House in Scotland is an example of designs begun by William Adam and finished later by son Robert. The firm continued under the brothers after the father died and they had received a number of commissions before Robert Adam left for his Grand Tour of Italy at the age of 26.

The library at Mellerstain House in Scotland is an example of designs begun by William Adam and finished later by son Robert. The firm continued under the brothers after the father died and they had received a number of commissions before Robert Adam left for his Grand Tour of Italy at the age of 26. Clearly Robert had aspirations as a gentleman and prided himself in letters home on his acquaintances among the British gentry and aristocracy whom he met in Italy. Adam studied with the painter Panini, Piranesi and others who honed his knowledge of classical art. He became a friend and competitor of William Chambers, who gained fame as the architect of Somerset House, the Strand, London.

Robert Adam returned to England in 1758 and took up his practice, cultivating clients among the highest circles. Many of Adam's greatest accomplishments were in remodeling or adapting the original plans for buildings under construction; he was not without enemies.

Robert Adam returned to England in 1758 and took up his practice, cultivating clients among the highest circles. Many of Adam's greatest accomplishments were in remodeling or adapting the original plans for buildings under construction; he was not without enemies.At left, the Oval Staircase at Culzean Castle, also in Scotland.

Adam's work is known for its sense of scale, of the human dimension in design. He adapted neoclassical, baroque and rococo themes in forms that delighted the eye without overwhelming the senses. His style has been repeated over and over in various "revivals."

Adam designed houses with layouts suitable for various kinds of parties, with rooms set up for promenading, greeting friends, and engaging in various activities. One room might be reserved for cards, another for dancing, another for conversation. Adam liked to emphasize the drama of the house by changing design themes and colors from room to room. Recurring elements of design such as the acanthus leaf were woven throughout, giving the rooms a feeling of unity.

Adam designed houses with layouts suitable for various kinds of parties, with rooms set up for promenading, greeting friends, and engaging in various activities. One room might be reserved for cards, another for dancing, another for conversation. Adam liked to emphasize the drama of the house by changing design themes and colors from room to room. Recurring elements of design such as the acanthus leaf were woven throughout, giving the rooms a feeling of unity.Ceiling designs were reflected in the carpet patterns. From time to time he chose special themes drawn from his experiences and from the popular design books that circulated in the period. For example, the ruins at Pompeii had been excavated in the 18th century and the wall paintings reproduced and published.

While the major elements of Adam design grew out of Palladianism and its inspiration in Italy, one can also identify the influences of French artists such as Claude and Poussin, whose paintings of idyllic classical scenes featuring ancient ruins, were very popular in the 18th century.

While the major elements of Adam design grew out of Palladianism and its inspiration in Italy, one can also identify the influences of French artists such as Claude and Poussin, whose paintings of idyllic classical scenes featuring ancient ruins, were very popular in the 18th century. Adam was an architect who wanted to control all elements of the design interior and exterior. He hired excellent furniture makers, such as Chippendale, and employed the most respected artists for interior decoration, such as Antonio Zucchi and Angelica Kauffman.

Dozens of volumes have been written about Adam, his buildings, his interior designs, his artistic theories and his lasting influences. You could easily spend your life learning about and visiting his creations. We'll be looking at a few more very soon right here.

In the meantime, we start with the sublime. This is the Adam-designed Pulteney Bridge in Bath across the Avon. Truly a beautiful structure.

In the meantime, we start with the sublime. This is the Adam-designed Pulteney Bridge in Bath across the Avon. Truly a beautiful structure. And to descend to the ridiculous, here is an over-the-top effort to convert a modern bathroom to the ideas of Adam's style. What do you think? Would you prefer a chandelier in your loo?

And to descend to the ridiculous, here is an over-the-top effort to convert a modern bathroom to the ideas of Adam's style. What do you think? Would you prefer a chandelier in your loo?

Published on March 23, 2011 02:00

March 22, 2011

The Wellington Connection - Duels - Part Two

"Gentlemen, are you ready? fire!" The Duke raised his pistol and presented it instantly on the word fire being given; but, as I suppose, observing that Lord Winchilsea did not immediately present at him, he seemed to hesitate for a moment, and then fired without effect.

I think Lord Winchilsea did not present his pistol at the Duke at all, but I cannot be quite positive, as I was wholly intent on observing the Duke, lest anything should happen to him; but when I turned my eyes towards Lord Winchilsea, after the Duke had fired, his arm was still down by his side, from whence he raised it deliberately, and, holding his pistol perpendicularly over his head, he fired it off into the air.

The Duke remained still on his place, but Lord Falmouth and Lord Winchilsea came immediately forward towards Sir Henry Hardinge, and Lord Falmouth, addressing him, said, "Lord Winchilsea, having received the Duke's fire, is placed under different circumstances from those in which he stood before, and therefore now feels himself at liberty to give the Duke of Wellington the reparation he requires." He seemed to pause for an answer, and Sir Henry replied, "The Duke expects an ample apology, and a complete and full acknowledgment from Lord Winchilsea of his error in having published the accusation against him which he has done." To which Lord Falmouth answered, "I mean an apology in the most extensive or in every sense of the word;" and he then took from his pocket a written paper, containing what he called an admission from Lord Winchilsea that he was in the wrong, and which he said was drawn up in the terms of the Duke's last Memorandum.

Upon reading it, it appeared that the word apology was in no place inserted, although the paper expressed that Lord Winchilsea did not hesitate to declare of his own accord that he regretted having unadvisedly published an opinion which had given offence to the Duke of Wellington, and offered to cause this expression of regret to be published in the 'Standard' newspaper, as the same channel through which his former letter had been given to the public.

The Duke, who had come nearer, and was listening attentively, said in a low voice, "This won't do; it is no apology." On which Sir Henry took the paper to the Duke, and walked two or three paces on one side with him, but immediately came back, saying, " I cannot accept of this paper unless the word apology be inserted." He then took a paper from his pocket, and was proceeding]to read, saying, "This is what we expect;" when Lord Falmouth, interrupting him, said, " I assure you what I have written was meant as an apology;" and he entered into a discussion, asserting that the admissions contained in his paper were the same as those, or were quoted from those, in the Duke of Wellington's own Memorandum. Sir Henry said, "My Lord Falmouth, it is needless to prolong this discussion. Unless the word apology be inserted, we must resume our ground." And, turning to Lord Winchilsea, whom Lord Falmouth had taken aside to converse with, he said, "My Lord Winchilsea, this is an affair between the seconds;" on which Lord Winchilsea retired.

After some little hesitation, Lord Falmouth said he did not well see how he could put the paper into any other form; and, referring to me, he said, half aside, "Do you not think it sufficient?" I said, "Yes, if you insert apology in the body of your paper." To which he replied, "Well, Sir Henry, I will do it in this way, and I trust that will answer every purpose. I will insert apology here in this manner "—writing with his pencil after the words " hesitate to declare of my own accord that (in apology) I regret," etc. Sir Henry then went to the Duke and spoke a few words, but came back almost instantly, and said to Lord Falmouth he was satisfied, or that the paper would do.

He then added, "And now, gentlemen, without making any invidious reflections, I cannot help remarking that—whether wisely or unwisely, the world will judge—you have been the cause of bringing this man (pointing to the Duke) into the field, where, during the whole course of a long military life, he never was before on an occasion of this nature." The Duke came forward, bowing coldly to Lord Falmouth and Lord Winchilsea, the former of whom seemed greatly affected, and stated he had always thought and told Lord Winchilsea that he was completely in the wrong; on which Sir Henry remarked that, if he did so, and came with the writer of the letter to the ground, his Lordship had done that which he (Sir Henry) would not do for the dearest friend he had in the world. Lord Falmouth then addressed himself to the Duke in vindication of his conduct, and was beginning to express the pain and anxiety he had experienced during the whole of these proceedings; but the Duke interrupted him, lifting up his hands and saying, "My Lord Falmouth, I have nothing to do with these matters." He then touched the brim of his hat with two fingers, saying, "Good morning, my Lord Winchilsea; good morning, my Lord Falmouth," and mounted his horse, and Sir Henry having also got on horseback and said, "I wish you good morning, my Lords," they both rode quickly off the field.

I took up the pistols, gave them to the Duke's groom to put into the carriage, and was walking away, when Lord Falmouth called to me to say that Sir Henry Hardinge had not verified the paper, and requested me to do so; which I did by putting my initials under the word apology, which was interlined, and signing my name at the top and bottom. Lord Falmouth repeated again and again how painful it had been to his feelings to be engaged in a business of this kind with a person for whom all the world, and he and Lord Winchilsea in particular, had so much respect and esteem as the Duke of Wellington; and on my remarking, "Then, why did you push it so far?" he replied, "It was impossible to avoid it. The fact is, Lord Winchilsea had been very wrong; so much so that he could not have made any apology sufficiently adequate to the offence consistently with his character as a man of honour without first receiving the Duke's fire. Had he done what he did in the heat of debate, or in the excitement of the moment, he might have easily retracted his expressions; but he had sat down deliberately and written and published a letter in the 'Standard,' containing accusations and insinuations which were highly improper. He certainly had discovered soon after that he had no right to attribute to the Duke's conduct the motives he had done; but this only rendered an ordinary apology the more inadequate; and he had, therefore, determined first to give the Duke satisfaction, that his expression of regret might have more effect." I said I could not agree with him in the view he took of the matter. That what might be justifiable, or even praiseworthy, towards an ordinary adversary, was very different towards a man like the Duke of Wellington; "for, indeed, my Lords," said I, "I never even contemplated the possibility of his being engaged in an affair of this kind, and I am filled with something approaching to horror, when, after exposing himself for so many years in fighting the battles of his country, after triumphing over all her enemies by a series of victories the most glorious and complete that ever adorned the page of history, I see he may still be forced to put himself on a level with other men, and expose to impertinence that life which he has so often risked for the benefit of us all." Lord Falmouth said, "On this occasion, at least, he did not risk his life. I assure you most solemnly, Sir, that on no other condition would I have accompanied Lord Winchilsea except on that of his acting in the manner he has done, and his declaring to me upon his honour that he would not return the Duke's fire." I said, "Indeed, gentlemen, I was never so agreeably relieved from the most painful suspense and anxiety I ever experienced as when I saw Lord Winchilsea fire his pistol in the air. I had before felt towards you both something like what I could suppose myself capable of feeling towards parricides; but I immediately saw that, although I might consider you wrong, you had erred perhaps through an excess of mistaken generosity; or, at all events, this is the construction you must desire to be put upon your conduct. Yet still I cannot help regretting you should have considered all this necessary, and forgotten the circumstances of your antagonist. But it is all owing to that cursed spirit of party, which now, as in all times, obscures the judgment and destroys the better sympathies of your hearts." Lord Winchilsea then replied, as if speaking to himself, "God forbid that I should ever lift my hand against him!" We had by this time reached the carriage, where, bowing, I took my leave, and drove directly home.

Having related these circumstances as minutely as my recollection enables me, I must now be permitted to mention the impression the distinguished actors in this affair made upon my mind throughout the whole of it.

In meetings of this nature the principals are supposed to commit themselves entirely to the guidance of the seconds, and thus become in their hands almost passive agents. On this occasion the Duke conformed himself strictly to this rule; and I could not help admiring how meekly and submissively he conducted himself through the whole of this affair.

To those who, unacquainted with the Duke, have only looked at his greatness, and recollect him at the head of his army, driving his enemies before him in all the triumph of victory from the Tagus to the Garonne in one tide of uninterrupted success, or who, after he had vanquished his great rival on the plain of Waterloo, and arrived at one bound under the walls of Paris, have beheld him in that capital in all the splendour of conquest, surrounded by emperors and kings, himself the most distinguished of all the members of that brilliant assemblage, fixing the boundaries of kingdoms, and controlling by his single word the destinies of the world, this may appear scarcely credible. To others who know the Duke well, it will excite neither wonder nor astonishment, for, whilst he is perfectly confident in himself, and well aware of the respect due to his great actions, no man assumes less. With the most perfect knowledge of human nature, he has always set a just value on popular applause, and has never for a moment allowed himself to be blinded by fortune, or intoxicated with praise. In his honest pride there is no arrogance, in his dignity no haughtiness, in his superiority no vainglorious display; but simple, plain, and natural in his manner, he is, without exception, the most unaffected of men. In all situations and on all important occasions he presents the same person. Calm, modest, unassuming, yet dignified, resolute, and firm, easy, unembarrassed; never losing for a moment his self-possession, never impatient or hurried.

Sir Henry Hardinge, the straightforward, frank, honest, warm-hearted soldier, full of zeal for his old Commander, full of indignation at seeing him obliged to seek reparation of this kind for an unprovoked and unmerited insult, but never allowing either to carry him to any improper warmth; clear, distinct, acute, decided, he went through the whole of this affair—to him most painful—with a degree of judgment, temper, discretion, and good feeling, which quite charmed me.

From Sir Henry's hint I kept as near the opposite parties as I well could without being remarked, and I have much pleasure in bearing testimony to the gentlemanlike behaviour of Lord Winchilsea. His manner throughout was exceedingly becoming; no haste, no forwardness, no presuming. His demeanour was gentle, calm, and unobtrusive. His countenance, which is pleasing, wore a certain expression of pensiveness, and, as I thought, of regret, as if dissatisfied with himself; and as he seemed to have put himself entirely into the hands of his friend, I confess I felt, in spite of me, a degree of interest and concern for him. He showed no levity, no indifference, but steady and fearless he received the Duke's fire, without making the slightest movement or betraying any emotion, except that when he raised his arm and discharged his pistol in the air, I thought he smiled, as if to say, "Now, you see, I am not quite so bad as you thought me."

I was sorry for Lord Falmouth, who was much affected, and seemed to feel deeply all the responsibility of the task he had to perform.

J. R. Hume.

Published on March 22, 2011 00:04

March 21, 2011

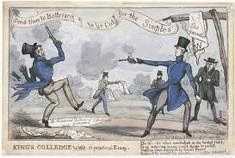

The Wellington Connection - Duels

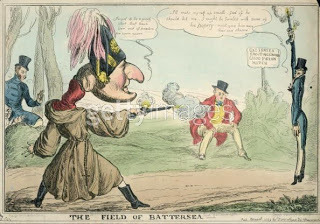

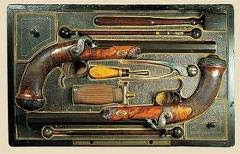

As Prime Minister, the most compelling point of Wellington's term was the question of Catholic Emancipatoin, the granting of almost full civil rights to Catholics in the United Kingdom. The change was forced by the landslide by-election win of Daniel O'Connell, an Irish Catholic proponent of emancipation, who was elected despite not being legally allowed to sit in Parliament and whose election prompted tempers to flare all around. The Earl of Winchilsea (George Finch-Hatton, 10th Earl) accused the Duke of having "treacherously plotted the destruction of the Protestant constitution" by publishing such in a newspaper of the day called The Standard. Wellington uncharacteristically responded by immediately challenging Winchilsea to a duel. On 21 March 1829, Wellington and Winchilsea met on Battersea fields. When it came time to fire, the Duke took aim and Winchilsea kept his arm down. The Duke fired wide to the right. Accounts differ as to whether he missed on purpose; Wellington, noted for his poor aim, claimed he did, other reports more sympathetic to Winchilsea claimed he had aimed to kill. Winchilsea did not fire, a plan he and his second almost certainly decided upon before the duel. Honour was saved, restored, etc. and Winchilsea wrote Wellington an apology. However, whether they loathed him or loved him, all those who knew Wellington were shocked that he had gotten himself involved in a duel. Everyone wanted details of the event; very few got them.

We are fortunate enough to glean the full details of the duel in the form a letter in the form of a report and known as - Dr. Hume's Report To The Duchess Of Wellington On The Duel With The Earl of Winchilsea. Hume was surgeon to the Duke of Wellington and head of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Saturday, 21st March, 1829. "Les moindres circonstances deviennent essentielles quand il s'agit d'un grand homme.'" ("The lesser circumstances become essential when it comes to a great man.'")

Sir Henry Hardinge