Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 28

April 2, 2012

Friends

Snow lightly fell soon after I learned about the death of my friend. I rescued some daffodils, broke some quince branches, which opened for me in warm water.

Peg was a wonderful mom, nursery school teacher, and writer. Here she is with me, Ellen Wittlinger, and Jo Knowles in November, taking a break from scribbling rather furiously on her yellow pad. She asked someone passing by the big wooden table we claimed in Greenfields Market to record the morning. Peg had patted her hair, and commented that being on chemo, she'd decided not to have it permed. "A waste of money, if it's going to fall out." She enjoyed her silver curls, but she was practical. She loved to laugh, and she faced facts.

We called her Peg or Peggy, but on her book jackets she was Marguerite W. Davol. I love the language in her picture books such as Batwings and the Curtain of Night, the joy of The Paper Dragon, and Black White, Just Right, a sort of love letter to her grandchildren.

Maybe what I most miss and what I'll always have is the belief we had in each other, which all my good writer friends – many of whom I know here, online — share. Those car trips, book fair tables, writing dates in Greenfields or Esselon were marked by celebration, complaints, and a little gossip among the work. Most importantly, we knew that whatever we said might be met with a laugh or a hug or concerned look, but always, always with conviction that we'd keep going on. No matter what, we'd write what we dreamed of writing. What a gift. Thank you, Peg.

March 24, 2012

Writing in the Lake District

I'm back from an amazing week spent with about fifteen children's book creators in northern England. Other guests at the inn sometimes pondered us as we wrote by fireplaces. "They're here to be inspired," I heard one tell another, and that happened. How could we not with views like this?

I made new friends and got to know some better, like my roommate, Amy Gordon, whose pencil scratched and eraser scrubbed as I click-clacked on my computer. I was so thankful to see old friends. What a thrill it was to hug dear Amy Greenfield in the country where she now lives.

Some of us took some short trips in the afternoon. My favorite was to Dove Cottage where William Wordsworth wrote. Here's view from the hill behind, where we saw daffodils bloom and heard British robins sing – "Oh, like the one in Secret Garden," someone said.

The cottage seemed quite dark and small inside, considering all the children and guests who were often there. I could better understand the long walks William and his sister, Dorothy, loved. We got to see William Wordsworth's skates and his friend Samuel Coleridge's opium scales. Beautiful old diaries and drafts of poems were displayed in the Wordsworth museum next door.

Here's a photo from Castlerigg, a stone circle made about four thousand years ago:

Mostly I wrote and took walks. Moss-covered stonewalls, and daffodils were steps away from the inn:

Here's a view with gorse:

After spending much of the day watching sheep graze, I was happy to come upon one up close and personal.

Two writers led amazing workshops, one of which led me deeper into the main character in my novel, and the other toward a foray into picture books. I found the little boy under my pen turn into a hedgehog and his mom into Mum when I wrote a picture book text, which of course still needs work, in a week. That was a first. Then a text that has been, more typically, coming in and out of drawers for years, took a turn that I think may set it apart enough to find a home. We will see. I guess I brought a little extra hope back, too.

March 12, 2012

Haunted Images: Finding a Way to Story

I don't expect I'll ever write a novel with fauns, lions, or even witches in it, but I've been inspired by reading A Lion, A Witch, and a Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis and Laura Miller's The Magician's Book: A Skeptic's Adventures in Narnia. Miller discusses her changing reactions to a series that enchanted her as a child, then later left her feeling betrayed when the Christian subtext was pointed out to her. After investigating what might give these books their power, she returns to some allegiance with the young reader she'd been. "At nine I thought I must get to Narnia or die. It would be a long time before I understood that I was already there."

I was moved by the information she provided about how Lewis created the series. She refers to the youth he described in his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, in which joy isn't synonymous with something jolly, but is tinged with yearning. He remembers a flowering currant bush, and a toy garden his brother brought into the nursery, and the sense of longing –"though not for a biscuit tin filled with moss" – that stayed with him, and recurred dramatically on other otherwise ordinary days. This might be the feeling he ascribes to Lucy as she receives her gift of a magic healing ointment. It's "the gladness you only get if you've been solemn and still."

We can't predict such feelings, or do much with an analysis, though I like Miller's suggestion that any small garden contains wild green growing things, just as a short story can seem to contain life. What's most interesting to me is the connection of haunting memories to C.S. Lewis's creative process, which was also dependent on imagery. Lewis and his brother played in a wardrobe when they were little boys. He dreamed of a faun under a gas lamp in a snowy wood when he was sixteen. He began a story called "The Lion," then put it aside. During WWII, children lived in his big house to escape bombing in London. All of these images stayed in his memory, and came into the books with a wardrobe that's a delightfully specific portal, with its smells and softness of fur coats that can make the children hot and sticky. No one knows why it's sometimes just a wardrobe and sometimes it lets one through to another world.

In "Three Ways of Writing for Children," Lewis wrote about how he he thinks through pictures, comparing writing to bird watching. He says imagination "stirs and troubles" the reader with a "dim sense of something beyond his reach." Much like what he called joy. We'll never know exactly how this felt for him, but why not let it inspire our own creative urges? When I look back to being a girl, I remember that sometimes quiet sometimes yearning self: the girl who felt sometimes shaky, but just as sure that someday things would change. Maybe that's what I'd call joy, and like his, it wasn't cheery, but had a strength that came from stillness. I accepted being shy and sometimes lonely, and found solace in reading books. Now, when I write my own, that girl is with me. Both shaky and sure, focusing on small things, and trying to hold a sense of something bigger beyond.

March 8, 2012

Gender in Books for Children and Young Adults

Gender in Books for Children and Young Adults was the topic of a panel at Harvard University, an afternoon event sponsored by the Athena program, designed to empower teen girls. Authors Sarah Lamstein, Jacqueline Davies, Padma Venkatraman, and I began by talking about what part gender plays in our work.

Padma spoke eloquently about the layers of history, explaining how her novel Climbing the Stairs was inspired by the story of her mother who grew up in India when Gandhi was nonviolently fighting for freedom from Britain, but at the same time, soldiers, equally passionate about freedom and justice, left India to fight alongside the British in the war against Hitler. And at the same time, Padma's mother was sneaking upstairs to find books that girls were forbidden to read.

Sarah Lamstein spoke of her novel, Hunger Moon, which shows a girl's moving attempt to be honest and fair to her brother. Gender isn't really a focus, but as Sarah explained, the 1950s setting gives a backdrop of different expectations for boys and girls. I nodded. Growing up during that decade, I slowly became aware of my mother's history of having worked during WWII, being asked to leave her job when the troops came home, marrying, moving to the suburbs, and getting depressed. I became a writer partly because I wanted to understand my mother's silences, which led to my being curious about other stories that seemed lost and bring them into more light.

Gender isn't the source of Jackie Davies's inspiration, but themes are woven in. Her acclaimed series of books starting with The Lemonade War is told by alternating points of view of brother and sister, and the novels seem equally popular among boy and girl readers, which is a beautiful thing. They explore ideas about family, friendship, money, competition, as well as push against stereotypes: you can read a bit more about this here at a Harvard Crimson article about the event.

When asked about what we hope to teach with our books, I spoke about balancing the strands of education and entertainment. Padma, with quite a bit of arm waving, said that emotion would be a better word than entertainment, and I agreed. Or engagement. What we most want are readers who will feel along with the characters. We discussed how girls are more often willing to do this as readers of what are sometimes called "boy books," while boys are less apt to read about girls. Would Harry Potter have been as popular if a witch instead of a wizard was at the center? We'll never know, or if anyone would have cared if Jo Rowling had resisted the request to use initials rather than a risk a female name on the cover. Such issues go beyond reading. Most girls are willing not only to read about boys, but dress like them, while boys may get teased or worse if they choose to dress up as a girl on Biography Day. Is it because people want to imagine they are someone with more power, and see women as having less?

There were so many good questions. We left wondering about the impact of calling this a panel about gender instead of using the words girls and women. What's gained and what's lost? Sarah, in her always generous way, brought up examples from history, showing that strong women in literature are hardly new, and cited the work of Pat Lowery Collins, scheduled to be on the panel but who had to opt out due to illness. We could have kept talking, kept naming books.

March 2, 2012

Winnie-the-Pooh as Poetry Buddy

Whenever a student mentions a memory of a parent reading a book, I smile as if that mom or dad just slipped into the room. There seems to be a pretty direct line between those happy moments and my students' interest in looking back. Rereading Winnie-the-Pooh, I remember my dad changing his voice for the characters, as my brother, sister, and I cuddled close. But like my students, there's much of the text I never noticed or forgot. This time through, I took note not just of Pooh's poems embedded in the prose, but how much the humble bear has to say about "this writing business. Pencils and what-not."

We get a glimpse into Pooh's process when "he was trying to make up a piece of poetry about fir-cones, because there they were, lying about on each side of him, and he felt singy." He studies the fir-cone, feeling something ought to rhyme with it, and when he fails, steers himself to other sounds. Shortly before the "Expotition to the North Pole," he composes a song, "singing the third and fourth lines before I have time to think of them." In House at Pooh Corner, Pooh asks Piglet what he thinks of a poem, and Piglet objects to one word. Pooh explains that this word wanted to come, so he let it. "It is the best to way to write poetry, letting things come."

It's tough for poets to find eager audiences, and Pooh keeps us company in scenes such as the one in which he approaches Kanga and asks, "I don't know if you are interested in Poetry at all?"

"Hardly at all," said Kanga.

Pooh tries to push on, "Talking of Poetry…" but Kanga is more interested in Baby Roo, who busily practices jumps.

In the last chapter of Winnie-the-Pooh, a party is held to celebrate Pooh's rescue of Piglet. When Pooh opens the present "He nearly fell down, he was so pleased. It was a Special Pencil Case. .. There was a knife for sharpening the pencils, and India-rubber for rubbing out anything which you had spelt wrong, and a ruler for ruling lines for the words to walk on, and inches marked on the ruler in case you wanted to know how many inches anything was, and Blue Pencils and Red Pencils and Green Pencils for saying special things in blue and red and green. And all these lovely things were in little pockets of their own in a Special Case which shut with a click when you clicked it."

I nearly fell down, too. Who wouldn't want to write with a case like that? I think I must at least capitalize Pencil.

For more Friday Poetry post, please visit Dori Reads.

February 29, 2012

Mush, Carrots, Blueberries: Ways to End a Picture Book

A student reporting on Goodnight Moon mentioned a professor who obsessed about circles, and her paper only encouraged me with all the O's in that title, which are pronounced with a circular-shaped mouth. Bven the letters on the cover slant as if they long to be a circle. My student mentioned the circles made by books read on laps, with a grownup's arms around a child. Another good circle is shutting a book to open it again, when a child demands, "Again."

Picture books invite hugs, which often appear as the last image in the book, as I mentioned in a post from last fall. I might now add the three-donkey hug at the end of William Steig's Caldecott-winning Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, which a student just reported on, though this semester I noticed a bunch ending with food. The round bowl of mush isn't featured on the last page of Goodnight Moon, when we're saying goodnight to noises everywhere, but it does warrant its own page near the end.

The Runaway Bunny, another classic by Margaret Wise Brown, ends with the runaway safely home with mother bunny, who gets the book's last line: "Have a carrot."

In another homage to circles, Robert McCloskey starts and ends Blueberries for Sal showing the little girl and her mother in the kitchen, making jam. After adventures with bears in the hills, the mother and Sal drive home "with food to can for next winter – a whole pail of blueberries and three more besides."

One of the most famous last lines in children's literature may be from Maurice Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are, ending with Max finding his supper in his very own room, "and it was still hot."

In Eric Hill's Where's Spot, a mother finds her puppy in a round basket. Tails wag as Spot enjoys his meal from a round dish.

At the end of Smoky Night by Eve Bunting, illustrated by David Diaz , neighbors come together, inspired by their once-battling cats turned friends. The protagonist's mother asks the neighbor to come with her cat "and share a dish of milk with us."

Some good foods are circular, or at least they can be. We're on now to Winnie-the-Pooh, who after all doesn't keep his honey in a box, or even a bear-shaped squeezer.

February 27, 2012

What Really Matters

I recently read a novel in manuscript and found so much that was good: the characters, the plot, the sentences. But I felt something small but essential missing. A crack in the purpose of the journey. I told my friend that I liked the places her character went to, but I wasn't deep-down sure why was it being taken.

A few weeks later, she wrote me back to tell me that she figured out the missing essence. Her answer was simple, but it gave me chills. I know now her characters may lift off the page.

The feelings that bring a character alive can sometimes be right in front of us. Or under our skin. Speaking recently to a group about BORROWED NAMES, I was asked why I chose the title. I explained how Sarah Breedlove, who grew up calling the white women she worked for Ma'am while they called her Sarah, claimed the name Madam before the name she took when married. Rose Wilder Lane also changed her last name when she married, and she kept it after divorce. Marie Curie, who hated publicity about her personal life and knew the radium she studied might be endangering her health, wanted to keep her name out of newspapers, so when going to hospitals registered under her mother's or sister's name. There was a lot of hiding, changing and borrowing, but a listener in the audience pointed out, "And you borrowed your own feelings and put them into the women."

Yes, we borrow from our characters, and take from our selves, when writing poetry or fiction. Sometimes a feeling missing from our work is right in front of us, clear as a shadow, and perhaps also that inexact. But some of what makes us grieve, hurt, or celebrate does and can go into the writing to deepen, elevate, or point a way through a story that's never just one person's story, but the reader's, the writer's, and those imagined on the page.

February 22, 2012

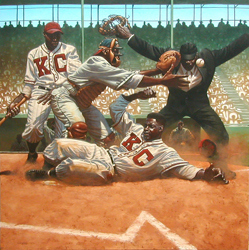

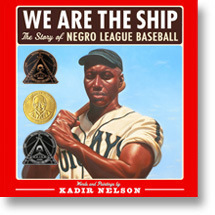

We Are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball by Kadir Nelson

Gleaming portraits juxtaposed with action scenes and framed pencil sketches made the walls seem alive at the opening of We Are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. We left for the auditorium to hear Kadir Nelson, who came from Los Angeles to speak earlier that day to some very excited second graders, who drew while lying on the gallery floor. Now he told a mix of grownups and children about how the book began from a big painting he did as a junior at Pratt. He became fascinated by these baseball players, and brought more paintings to Sports Illustrated, where some were published, beginning a career working in magazines before publishing for children.

While working on various projects, Kadir kept on painting the baseball players on large canvases. He sometimes combined a historic image with action shots he make by posing himself in uniform, putting his camera on a tripod, and setting the timer. He studied scale and chose angles that emphasized size: "the Negro League is an epic part of history to me, so I wanted to give the players their due." He told us of his careful research and checking the time and place of each part of the book, putting together the correct players with the right uniforms and details of each ballpark. And he confided a mistake he'd made before writing this book about getting a detail wrong, and what he learned from that.

He brought his paintings to Andrea Pinkney, an editor at Disney, who encouraged him to write the text, which was a surprise to him, since he'd been a boy who hated to read, especially about history: it wasn't until he was a teen, that he found subjects he wanted to read about. He read a lot of books and talked to a lot of people until one day he heard: Seems like we've been playing for a mighty long time. And he knew he'd found a way to tell the story through the collective voice of the players.

He brought his paintings to Andrea Pinkney, an editor at Disney, who encouraged him to write the text, which was a surprise to him, since he'd been a boy who hated to read, especially about history: it wasn't until he was a teen, that he found subjects he wanted to read about. He read a lot of books and talked to a lot of people until one day he heard: Seems like we've been playing for a mighty long time. And he knew he'd found a way to tell the story through the collective voice of the players.

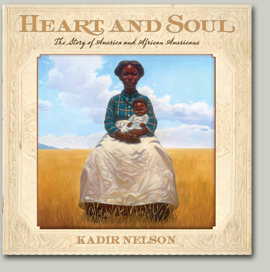

Kadir Nelson started out thinking he'd do three paintings about the Negro League, but it became more than thirty for a book that took about seven years to create. During that time that he was working on other projects, winning many honors. Most recently Heart and Soul: The Story of America African Americans is doing just what Kadir expressed is his hope as a creator. To take "stories that are sometimes negative and turn them around into something beautiful."

The show will be up through June 10, and Kadir Nelson will speak again on April 1, along with NPR's Scott Simon and Jackie Robinson's daughter, Sharon Robinson, about their picture book, Testing the Ice. Please click here for more information.

February 20, 2012

Ann Turner Speaks about Writing for Teens

On Saturday morning, Ann Turner, the author of more than fifty books, gave a talk sponsored by Straw Dog Writers. Ann suggested that writers might ask ourselves what age person is most alive for us inside, then tap into that person. She said that when she writes for teens she doesn't so much remember who she was than become that girl, taking on the feelings of vulnerability, of being wrong, not fitting in, and desiring passionately to meet the world with love.

Ann read from her most recent novel, Father of Lies, the story of a bipolar girl in Salem at the time of the witch accusations, which explores expectations of who might be crazy and who evil. She also read poems from Learning to Swim, a slim, moving memoir of childhood sexual abuse she wrote to give readers comfort and courage. The child in the poems faces down fears of the muck of a pond, the uncertain bottom, and trusts her own ability to float, coming at last to move with ease, as learning to swim becomes a metaphor for healing. The poems about the girl are framed by the voice of a teen, the age intended as the book's main audience, who relays the challenge, necessity, and triumph of telling a trusted someone what happened. This beautiful, brave book should be in every school library.

Ann's picture books and novels often have historical settings, and when I asked how she decides how much background information to leave in, she said it was mostly a matter of practice and intuition, comparing it to baking bread: the baker keeps adding flour until she recognizes the time to stop by its look, heft, and texture. The writing should also lead the reader through unfamiliar territory by feel, and Ann mentioned that reading your work aloud is a good way to gauge this. She also warned, "if you're doing research you can pretend that you're writing. And you are, but…" Yes, I know that fragile pause. She said that a desire to be right can take over the story. "There's a point to stop and let story take over. Like swimming, you need to let the current take you where it will."

She answered a question about being in a writing group, and said what she finds most useful is when others don't stress what doesn't work, but instead ask questions, exposing areas she realizes might be more explored. Finally, she spoke of letting your material speak to you: "I think there's something magical hidden in the heart of the story that if we listen, it will tell us where to go." For her it's prayer more than technique that shows a way.

February 13, 2012

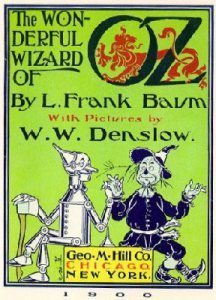

Thoughts on The Wizard of Oz

Most of my students enjoyed The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, with many, though familiar with the movie, reading the book for the first time. We leave behind Charlotte's Web, with its prose that E.B. White labored over for years, simple and as perfect as can be, for a work begun as a story Frank Baum first told to his four sons. It shows signs of its origins in its episodic nature – That's it for tonight, boys! — and the style is closer to that of fairy tales, also from an oral tradition, in which tellers dived into a story before the audience might scatter. In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, I kind of love that Uncle Henry's first words are, "There's a cyclone coming, Em."

It's not a style I expect or particularly want to achieve in my own writing, but reading these works, I'm reminded to sometimes stop obsessing about how to get my characters to leave a room. It probably won't involve cyclones or setting forth with a basket of bread or an ax, but a short, direct sentence can do the trick.

We talked about characters, and their connection to archetypes, comparing the foursome of Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Cowardly Lion, with Harry Potter, Hermione, Ron, and Hagrid in another popular book which also addresses magic, witches, friendship, intelligence, and bravery and was published about a hundred years later. I asked what people thought of Dorothy, and one girl told us how she wanted to be her as a girl. Not only did she have red shoes, but she demanded her family call her Dorothy. "But now I found her annoying."

Other concurred. What some might see as a Taoist or take-it-as-it-comes attitude, others found bland and silly, and wanted her to wake up. If she was going to kill a witch, they didn't want that to be by accident. When the wizard tricked her, where was the angry response?

But one student pointed out that her lack of complexity was what allowed the real heroes of the tale, the Scarecrow, the Tin man, and the Lion, to grow. If we were too involved with Dorothy, we might miss what makes those characters endearing. The lesser importance of this girl is reflected in the books early covers (and W.W. Denslow's depiction of Dorothy is no Judy Garland). Another student pointed out that this was the case with the beginning of Harry Potter, too. Harry's buddies seem more complicated as things start out, something that even he recognizes. I liked when Harry showed a talent for Quidditch, and felt proud that acclaim came from something that he did, rather than being famous for a lighting bolt-shaped scar on his forehead or history. This is an idea that's sticking with me, one of the great gifts of teaching, though I'm not sure what I'll do with it. Except that it turns around the way I often think about books, with one main character in the center, and it's always great to see things from a new direction.