Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 25

June 29, 2012

The Snowy Day and The Art of Ezra Jack Keats

Last night Peter and I attended the opening of a show highlighting the work of Ezra Jack Keats at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. Claudia Nahson, who curated the show which originated at the Jewish Museum in New York, , spoke about Ezra Jack Keats’s (1916-1983) history. We learned that he had a rough time growing up as small, artistic, and poor in the Brooklyn he’d later picture in his books. He often felt invisible, and started drawing early, thinking that the only way people would see him was if he made art. His mother showed off the pictures he drew on the kitchen table. His father bought him cheap paints and paper, but, as a struggling immigrant from Poland, worried whether his son could make a living. Hoping he’d consider another career, he told him that the paints he gave him had been traded for soup at the diner where he worked, by artists who were desperate to eat.

Ezra worked as an assistant for WPA muralists, then drew backgrounds for Captain Marvel. “Background man” was a job Claudia Nahson posited as a metaphor for his aesthetics, as he continued through his career to pay attention to things like trashcans and graffiti, finding beauty where few saw it, and bringing it to the forefront. He served in the army in WWII, then studied in Paris on the G.I. bill, which was about when he changed his last name from Katz to Keats, probably because of anti-Semitism. He spent much of the 1950′s illustrating book jackets. Eventually he was asked to illustrate a children’s book, Jubilant for Sure by E. H. Lansing, which led to more work. He noticed that minorities weren’t often represented, and changing that was part of the motivation for writing and illustrating his own books.

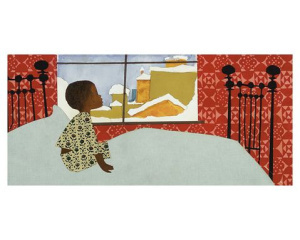

The Snowy Day, which won a Caldecott Award in 1963, was the first book he both illustrated and solely wrote. His protagonist, Peter, was inspired by photographs he’d clipped from Life magazine twenty years before, put on his wall, put away, then tacked back up.

Claudia Nahson called The Snowy Day the first time an African American was represented in a full color picture book. The technique of collage was new for Keats, and he made Peter older through a series of seven books, ending with Goggles in 1969, which was cited as the most autobiographical of his books, and was based on his memories of being bullied.

Ezra Jack Keats would go on to create many more books. He became interested in the simplicity and paring down in Asian visual art and haiku. At the show at the Carle, we see silhouettes of birds and plants on hand-marbled paper he did for In a Spring Garden, edited by Richard Lewis. He always strived to use very few words. We were told about him going to a writer’s conference where people talked about how many words they wrote in a year. He said, “Three hundred. And I’m happy.”

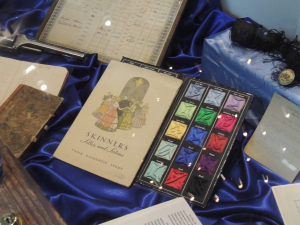

The wonderful show includes work from the span of his career, as well as a generous sampling of diaries, letters, sketches, storyboards, and a paint box. A display chronicles some depictions of African Americans in picture books. The show will be open through October 14. To get more of a sense of what’s there, click on the link to the Jewish Museum at the top, where a video will give you a virtual tour of the show which began there. I’ve long been a fan of The Snowy Day, but it was fun to learn how much more there was to Ezra Jack Keats’s career. I know I’m going back!

The wonderful show includes work from the span of his career, as well as a generous sampling of diaries, letters, sketches, storyboards, and a paint box. A display chronicles some depictions of African Americans in picture books. The show will be open through October 14. To get more of a sense of what’s there, click on the link to the Jewish Museum at the top, where a video will give you a virtual tour of the show which began there. I’ve long been a fan of The Snowy Day, but it was fun to learn how much more there was to Ezra Jack Keats’s career. I know I’m going back!

June 26, 2012

Ninety Pages Down, and Feeling Grateful for the Workout (Really!)

It wasn’t so very long ago that I wrote a blog post called One Hundred Pages about my grouchiness when my writing group thought I might try to cut down part of my manuscript by about a third. It seemed impossible, but it turns out it wasn’t. It seemed like it would be tortuous. From this point about two months later, I’d say it mostly hurt at first, like the proverbial bandaid, but my husband says, no, I’ve been grumbling throughout. I hope not every day. There definitely is an ouch element to stripping away what you painstakingly constructed. But as I hacked out holes, I found new things to insert. Putting one scene against another brought out new elements in both. There’s definitely more muscle to the piece, less sag. I’m thankful to my writing group for raising the bar, even if I know I’ll grumble again. I’ve still got the second part of this manuscript to bring them.

But for most of the summer, I’ll be working on that in solitude, hoping to keep that manuscript on its healthy diet (thanks for the metaphor, Ellen!) and working out every day: no excess conversations! No lumpy descriptions! I’m glad I did the trimming (can we use the word trim? I’m trying to stay away from hacking away) and glad to embark on new material, cheered on by facebook friends – Thank you! I’ll be doing the best I can to get everything right as it felt during a walk with my friend Jess around The New England Peace Pagoda today. The world is so beautiful. Sometimes we don’t need to add much.

June 19, 2012

Gems in the Dust

This weekend Peter and I drove to Wells, Maine to help celebrate the grand opening of Shellback Artworks, a shop our friend Steve Lavigne, with huge help from his wife, Denise, is opening to sell comics and art supplies and where Steve will teach classes to kids. There was free pizza and lots of good will through the day, but maybe my favorite story was the one Steve told me about three little boys who checked out some racks, raced home to get some money, doled out their quarters, then sat side by side on the steps with three heads bent over their comic book.

Peter and I also found time to walk on the beach and eat fried clams and charbroiled shark. On our drive through New Hampshire, enjoying lupine season, we stopped at Henniker Book Farm (our timing was good, as I can see from this web link that they’re closed this week, as “grandchildren and lobster trump books.”) The poetry section was amazing, and I found an old book about the history of my favorite library, but my happiest find was this collection of letters written by a friend of someone I’m writing about.

Peter reminded me of my initial elation as the weekend passed and I read, skimmed, slogged, and eventually grumbled. Fourteen hundred pages can hold a lot of tea parties in which not much happens. I was reading about a time in which both Henry David Thoreau and Nathaniel Hawthorne died, and I’m pretty sure Ralph Waldo Emerson’s daughter would have attended those funerals, but nothing is said about them. Her neighbor Louisa May Alcott wrote Little Women, but that isn’t mentioned.

But of course I can read about those events elsewhere. What you want from a letter collection are the small details you can’t find elsewhere. I did get the fabrics of some dresses and the varieties of pears in the Emerson’s small orchard. May Alcott showing off a spider she painted in the corner of her bedroom wall could be worth the twenty-five dollars I paid for these two volumes, at least along with Ellen’s gifts to her when she went abroad: four bottles of champagne, a hanging pin cushion to nail to her berth, and her copy of Portraits de Femmes. She advised May to bring a shawl-strap for her blanket, a basket of oranges, and napkins (handkerchiefs won’t be large enough) to spread over her chest when lying on her back to eat broth or porridge.

We learn that Mrs. Emerson had a habit of screaming if she stubbed her toe or pinched a finger, then might call out an assurance no bones were broken, then shriek again. I’d have enjoyed some more screams through the dense pages, but I did develop a sense of Concord, MA as seen from one particular household. Here are a few notes I pulled from the thick first volume:

May – catbird, blue jay, song sparrow, wood pigeon, red-shouldered blackbird, oriole

Massachusetts scenery isn’t like Italy, but the moral atmosphere is higher

stereoscope showed houses on Main Street and along the Mill Dam – Mr. H seemed enchanted, as if he hadn’t walked by them hundreds of times.

1868 burglaries, now Mr. Emerson won’t leave the silver cream pitcher

Such finds are the reasons I urge those writing about history to end with the internet, which is good for fact-checking, but to begin with books, which are full of clutter, but hold gems not yet ferreted out. I’m on a revision of a revision, and didn’t think I needed new material, but fresh details lend zip to my tired eyes and finding places for them can change the shape of the whole. It’s like Steve painting the walls of the shop, opening boxes, filling shelves, and hanging banners. You can plan all you want, but what can make something great are surprises like three boys huddled on the steps waiting to turn another page.

June 14, 2012

Writing and Teaching at Simmons

Today I joined colleagues who teach in the MFA in Writing for Children Program at Simmons speaking at a Children’s Literature Association Conference at the Boston Campus. We each had been asked to read some and talk about our lives as authors and teachers.

Anna Staniszewski read from her first novel, My Very UnFairy Tale Life, and spoke about moving between writing this funny, upbeat book and a novel that was more wrenching. Ellen Wittlinger read from her novel set in the cold war, This Means War, and spoke about the writing process, which so often switches between our beautiful dreams and the harsh reality of seeing the long way we have before we reach that initial, gorgeous vision. I spoke about my grandmother’s attic as the place in which I learned to research, and read three poems from Borrowed Names. Anita Silvey spoke about her most recent work of narrative nonfiction, The Plant Hunters, which tells the history of scientists who risked their lives collecting plants which both expanded our knowledge of the world and, because of their medical use, saved lives. Anita spoke of how she located primary sources, sometimes choosing her subjects because of pictures and artifacts such as plant collecting cases that were available for her to see firsthand. She also told us how she spends about six months developing a proposal, rather than waste three or four years researching and writing without a clear direction.

Here is Anita, Ellen, Anna, and me in a photo taken by the program director, Cathie Mercier.

Perhaps since the audience was one largely of scholars, we were asked by more than one person about how one reconciles putting forward great books as teachers, setting high standards, and … just writing, which for me and many starts as writing badly. All of us counseled separating the creator from the critic as much as possible, using whatever tricks one could, such as finding a name for that inner critic, and saying whatever must be said to get her or him off our shoulders and waiting quietly for a turn. I hope we didn’t sound glib, because we understand this can be truly painful. Reading, and gently tearing things apart to understand how a book is constructed, is useful, but really has to be pushed to the back of one’s mind as one writes.

The final question was from an academic who loves children’s literature, and worries about its survival in a climate in which good books go unpublished or get neglected. As authors, we share her concern, but Anita left us leave with hope, speaking of signs of an upturn and the possibilities of new avenues of publishing. I was happy to leave with a short list of books to read, and to have looked into the faces of people who care about good words.

June 11, 2012

Compressed Vacation

For most of the years of my daughter’s childhood, we rented a house for two weeks in southern Maine. Emily’s friends and their moms would sometimes visit. Some of our relatives and almost-relatives would come for a few days to relax and smell and hear the ocean. There are so many great memories. Now Emily lives across the country, and for the past two years her job has meant she can get away for a long weekend, not two weeks. So we just celebrated two days at home, catching up with us, her bed, the dog, the cat, Nell, who she’s known since kindergarten, her grandparents, Aunt Chris, and her favorite restaurant, The India House where they know she’ll order chana masala and a house salad.

Then our family of three headed for Maine for two and a half great days. We saw our friend Steve Lavigne, his wife, Dee, and her mom, while they were busy getting ready to open a comic shop in Wells next weekend, which you can read about on one of Peter’s blogs.

Emily and I both ordered scallops in a Kennebunkport restaurant where we saw the sun set over the ocean.

And Emily and Peter had Annabelle’s (amazing) ice cream in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Peter and I are glad to be home, but it’s always sad to take Emily to the airport, even though I know her roommate and dog will be so glad to see her. It’s your turn, Colleen and Henry! Hope to see all of you in California before too long!

June 8, 2012

Natasha Trethewey Named Poet Laureate

I’m happy that Natasha Trethewey was named poet laureate this week, and have heard she may move from Georgia, where she’s been teaching at Emory University, to Washington, D.C., which would make her the first in this position to do so.

I loved her book Native Guard, which won a 2007 Pulitzer Prize in poetry. It links her memories of seeing old Civil War sites, some labeled, some not, with her view of their history. A long section focuses on one of the first black regiments. Her most recent book Beyond Katrina: A Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, combines poetry and prose, memory and attention to the present, the story of her brother and a broader political view. Domestic Work includes many poems about growing up in the South, including Hot Combs, Cameo, Family Portrait, Mythmaker, Saturday Matinee, and White Lies.

Here’s a post I wrote after hearing her speak at UMass-Amherst, where she earned an M.F.A. in poetry. You can read more and hear clips of the poet reading at Tara’s blog, A Teaching Life. And for more Poetry Friday celebrations, I hope you’ll visit Jama’s Alphabet Soup.

June 5, 2012

Writing and Tears

Is there a way to sit down to write memories, funny stories, or adventures about made-up children in made-up lands without risking crying at the computer, having touched on tender places? I was just asked about this from a thoughtful, sensitive person embarking on a summer of writing and who would rather not do this by a box of tissues.

Clearly some people can write anything without feeling overwhelmed. Journalists have to write about catastrophes all the time. And I expect many of those writing dystopian novels showing the world at its worst may work on chapters while eating lunch.

But I find that sitting quietly can put me in a lot of moods. Sadness, which caregivers may neglect during days of making an effort to look bright for other people, may take this chance to call for attention. You may not mean to write about a loss that’s pushed back to get on with the day, but it may take its chance to rise at the writing desk, just as it might when a song comes on the radio while driving to get groceries, or in the quiet when your head hits the pillow. I’m not a therapist, though I’ve been to one, and think if tears come, they do so for a reason. And happiness can be found on the other side. Tears do dry, and they can be healing.

Someone surely knows of a writing practice that avoids the dark recesses of the mind, but I’m not sure I’d choose it, any more than I’d want a life without love, though I know that means eventual loss. My mom was the sort who advised, “Don’t dwell on things. Leave the past behind,” and I became someone who dwells kind of for a living, and unburies hidden stories of history, work that sometimes makes my own hidden stories fly up with the dust.

This kind of work isn’t for everyone. But those who choose to write and find tears come should know they’re not alone. And if it hurts too much, it’s good to ask for help.

June 4, 2012

Writing from a Vulnerable Place … and Writers Camp

This summer, teachers and librarians who want to experience the joys, anxieties, and muddles that their students experience when writing can find inspiration and support through Teacher’s Write! A Virtual Summer Writing Camp begun by Kate Messner. I met Kate through blogging, so know first hand how the people we find on our computers can help develop our thinking and become friends.

Some who signed up mentioned being scared, and Kate responded with a great post about Writing and fear. I’m thinking about her words, and those of Jo Knowles who adds that we might as well have fun here. She offers a great kitchen-centered prompt as one way to begin, which is usually the hardest part. Here I’m adding thoughts that theirs stirred in me.

Teachers have to look smart and responsible so much of the time, which may not be the best pose to take when writing, which, when it’s flowing, can ruffle us up. We’re going to look ridiculous and leave messes. And should remember that this is good. When we feel our bellies tighten, it’s a sign to keep going, not stop. Our eyes may mist, and we can take out a tissue, but it’s fine to let tears flow. Of course writing doesn’t have to be emotional, but it may be, especially if you touch on a story that feels as if it’s been sitting inside you too long. Maybe you’ll just be funny, or write a silly poem, or an adventure taking place on another planet. Still, you’re going to be faced with challenges. If you’re like me, little comes out right at first, which means you’re going to have to move through more frustrations than we do when writing papers, evaluations, or letters home. Then we want to sound like an authority of some kind. But as creative writers, we want to connect more than instruct, and we may do that most when writing from places we don’t necessarily show when we’re wearing good clothes and loud shoes. Those who are used to being the people who others come to for answers, can find it tough to say, “I’m sorry, I don’t know.”

But it’s a beautiful place to begin.

May 31, 2012

A Thousand Stories

We could have been at the beach or barbecuing or something a bit more three-day-weekendish, but Peter and our friends Dan and Jess decided on lunch in South Hadley, then a pretty walk up the street to the Skinner Museum. This is part of Mount Holyoke College, opened by one of their benefactors decades ago as a place to put his collection made in the tradition of Cabinets of Curiosity, except this one fills a few buildings. The part of his collection that’s on display is in an old church saved from a nearby town which was flooded to make the Quabbin Reservoir, to provide water to pipe to Boston.

Museum founder Joseph Allen Skinner was the son of a bootstrap-type of the nineteenth century, who starting with next to nothing dyed silk, then built mills that made him millions. Some of the wealth was used to help fund a chapel, state park, hospital, and library in nearby Holyoke; some went into his traveling and this collection which has something for everybody and maybe something for nobody, too. You’ve kind of got to love a spare arm.

Much wasn’t yet labeled, but, especially with Laura-Ingalls-Wilder-era farm tools in the basement, it was fun to guess what things were used for and how. As Dan said, you could sometimes figure things out by looking, which you can’t with a computer. We had a good day. As the founder wrote about the museum billed as offering a thousand stories, “It is fine and I always find something new to look at.”

May 24, 2012

Taking Flight: Audubon and the World of Birds

On Sunday Peter and I visited the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, MA for an exhibit called Taking Flight: Audubon and the World of Birds. I learned that John James Audubon was born on a sugar plantations in Haiti in 1785, then after his mother died, went to France with his father, a naval officer. So as not to have to join the military under Napoleon, when he was eighteen he was sent to manage a plantation in the United States, but seemed to spend more time playing music, dancing, and walking in the woods than at work. Eventually he set off by foot, boat, and horseback, trying to paint every bird in America. He used various mixtures of graphite, oil paint, egg white, chalk, and pencils to paint birds as preparations for etchings, which would be hand-colored. When he couldn’t sell many subscriptions for a book in the United States, he left for England, where he traveled on horseback with 300 drawings in a heavy tin-lined portfolio. He made sales where he could, entertaining with stories about his adventures and doing bird calls. It was mostly a hardscrabble life, with few hints that one day, long after his death, a single copy of Birds of America would sell for over eleven million dollars.

Naturalists like Audubon shot and stuffed birds as a way to study them before most photography was available. Still, those birds made to look alive with arsenic and other chemicals have usually depressed me when I’ve seen them in museums and nature centers, though I understand it’s about heritage: the question being like what to do with a fur coat some inherit? Maybe it was the choice to take some of the stuffed birds, (which were were part of the museum’s earliest collection, about a hundred years old), out of glass cases, set between the engravings and under bright light, that let me see them more as something once alive, vibrant with second chances. They were surrounded by displays such as a small shelter with stuffed owls perched high, and where we were invited to listen for a recorded mouse noise, and test our hearing against the mightiness of an owl’s. I admired the craft supplies laid out so people could try to make a nest as gorgeous as that of a bower bird’s, and big chalkboards where children could measure the span of their arms against wings of various birds. Short videos showed masses of birds in fight, charting swarming patterns through sky. This wonderful exhibit will be up until June 17.

After we left, Peter and I drove to Pittsfield State Forest to picnic. A woman with a golden retriever we admired told us of the five mile loop up the mountain where we saw the state’s highest body of water, an amazing view of the Berkshires, and lots of what the park calls azaleas, and what I called honeysuckle as a girl, and what internet sources tell me can be called honeysuckle or native azalea. A lot of pink under a blue sky. Birds called.