Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 26

May 22, 2012

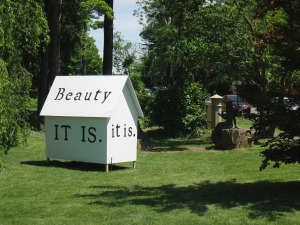

The Little White House Project

Forty little white houses with parts of Emily Dickinson’s poetry stenciled on the walls have been created by Deerfield Academy student Peter Krasnzekewicz, and set up around the Emily Dickinson Museum. I recently walked from Jones Library down Amherst’s Main Street, past these houses, though most are clustered in the garden by her house or the one next door where her brother and his wife, her dear friend, lived.

“Dwell in Possibility” will be on display until the end of June and can be seen at no charge. I liked recognizing words and phrases, relying on memory, and settling for spaces between words, as I encountered a new way into or around some of Emily Dickinson’s best known poems. Would she have liked the way we wandered, piecing together broken lines? I don’t know, but don’t we often grasp poetry a word or clue at a time, swept along by questions as much as completion?

May 19, 2012

See You At Harry’s: Celebrating with Jo Knowles

It’s a very good day when I get to sit across from Jo Knowles in a café while we and other friends write together, drink coffee, and catch up. But you can almost hear the planet hum on a sunny May afternoon when I can get a new book, signed in silver, and give a congratulatory hug to someone who’s worked so hard and so faithfully to create something beautiful. See You at Harry’s is a novel filled with love, humor, family, friends, sorrow, and hope. Here’s Jo surrounded by family and friends, all of us ready to listen to a few pages.

And heres’s Jo with Kara LaReau. How cool and seet is it to dress to match the book cover?

And one of the world’s kindest, smartest authors with me and Ellen Wittlinger after eating ice cream with all sorts of toppings, chatting with friends, hearing kids bat a volleyball, with littler ones running by in clothes soaked by water guns, with a bit of chocolate on some faces, perfectly happy, as were we all. Leaving with a novel that doesn’t paint life as sunshine-y every day, but shows the power of love and truth to help us move forward. Lucky to have others who understand.

May 17, 2012

Remembering … and a Little Bit of Research

Yesterday I gave a dinner talk to the Pioneer Valley Reading Council about my work, and part of my message was that all research doesn’t need to end up in that genre called a research paper. I spoke about how not having taken any history courses in college, my life writing about history began when I was in my twenties and sorted through some of my Grandmère’s things after she died. This archiving, which my uncles called cleaning, raised as many questions as answers about a woman whose accent and habits sometimes embarrassed her three sons, but as granddaughter, I was totally smitten. Genevieve brought a sense of style from Paris to New Jersey, even if she didn’t update it over passing decades: she stuck with blue eye shadow and espadrilles into her eighties, and never wore pants in her life. Here’s a picture of her when she was in her twenties, in that roaring decade.

Not long before she died, she’d told me that I might have anything from what was sometimes called her art studio, sometimes a side porch. Here are a set of her dried paints and some sketches she did of patients as a Red Cross nurse during WWI:

I saved paints with gorgeous labels and fragile sketchbooks, and tossed paintbrushes that didn’t brush. That kind of looking, assessing what to keep and what to throw out, pondering, seeking clues about a life, is what I do as a researcher. In my talk, I went on to suggest ways students might mix imagination, which may be as filled with treasure and junk as attics, with research.

When I spoke with some teachers who lingered afterward, I was happy that one told me, “You just gave me my June lesson plan,” but more came up to talk about their own family memories. One woman told me of a deferred need to put down stories, including one of an ancestor whose father forbid her to become a nurse, and who ended up nursing this man in his old age. Another woman told me that she recalled asking her mother about her grandmother’s stories, and being told, “They passed away with her,” and realizing she might soon tell her grandchildren the same thing about her mother. Cutting short the third time she told me, “I’m not a writer,” I said, “Just put down memories when they come to you, without worrying about language or structure. Use ten minutes here or there.”

She nodded. I hope that was a promise. Teachers are so busy caring for others, but I hope some take the chance to write when their students do, perhaps even sharing with them some parts of their real lives, which may be as important as anything on the curriculum. The first story I ever published was about going through my Grandmère’s paintings, paper fans, saved menus, and rosaries, learning from what my dad and uncles would have thrown away. So much of what I write now comes from what was saved, but often carelessly, remaining at least half-hidden. Fragile, shadowy, and important, like the short stories told in a rush as I packed books, wound an extension cord, and tried to let my colleagues know that everything they remember matters.

May 11, 2012

Edith Wharton on llluminating Incidents

When I was moaning about plot challenges recently on Facebook, my friend Jen Groff suggested that when I figure this out, I should run a workshop called “Plot for Poets.” I haven’t figured it out, and I’m not running a workshop, but I like her title and I’m reading Edith Wharton’s The Writing of Fiction, which might be the text for this class. Edith Wharton wrote a lot of great fiction in the same era that her friend Henry James was also writing novels and trying to figure out the aesthetics of a form that could seem wayward and bulky. But I don’t see as much heavy lifting, the marks of trying to figure out rules, in Wharton’s fiction as I do in James’s. (Not that I’ve read that much, let’s be clear: I lose patience.) Edith Wharton was known for grace, reticence, and heroic strength in a life both privileged and trying, and you find all of this in her novels. Her slim book on writing could be placed on the elegant end of how-to guides. She doesn’t discuss plot in terms of lines or triangles, but as light, which might radiate back from illuminating incidents and an end that seems inevitable. Not just characters, but place, should contribute. “The impression produced by a landscape, a street or a house, should always, to a novelist, be an event in the history of a soul.”

“No conclusion can be right which is not latent in the first page.” I’m playing with images in the first and last chapters, realizing that I have pine boughs on page one, and can slip in evergreen nicely at the end. This echoes what Blake Snyder says in Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need which I’m also finding useful on plot. But of course since it’s about screenwriting, discourse is left out. Like most of us twenty-first century writers, I can lean too much on dialogue, which Wharton warns can be a method that is “wasteful” and “roundabout,” best used by those who dare start in the middle and aren’t tempted to use conversation as a setup to let readers in on things they need to know. Wharton mentions Trollope’s “least good tales, rambling “on for page after page before the reader, resignedly marking time, arrives, bewildered and weary at a point to which one paragraph of narrative could have carried him.”

I’m not sure I can or want to with use dialogue just as she advises – “sparingly as the drop of condiment which flavors a whole dish” –but she gives much to ponder as I trim to bring out a shape. Wharton writes that the length of a novel must be determined by its subject, but when composing, we shouldn’t forget that “one should always be able to say of a novel: ‘It might have been longer,’ never: ‘It need not have been so long.’” Okay, back to paring down.

May 7, 2012

Writing Across the Room

How many of us would be writers if we didn’t have optimism so hefty it rivals that of someone like my friend, Jess, a yoga teacher who was so delighted by our trip with our husbands to Lilacland that she did a few cartwheels? “Couldn’t you just stay here forever?” she asked among the dozens of blooming trees. Her husband, Dan, a lover of truth, replied, “No.” But the hill smelled sweet, and the good company was a change from a week of cutting pages I’m no longer numbering, but calling a bunch. I’m trying to think of this not as trimming but getting to play with colored pencils. Cutting with gusto what I’d patiently built up, it’s a time for coffee, not herbal tea, Springsteen, not Vivaldi.

Once I got over the shock of how much I’d have to leave behind and read the notes a writing group member provided, I could hear the positive: “whittle away the slower, more repetitive scenes so that the magnificent scenes can really shine.” Thank you for that, Lisa. And reminders to trust the reader to make leaps. I’m leaving some holes, filling in others. When I look longer at some scenes, I find something hidden: like the photos Peter recently took of a nest with two eagles. Only when he looked at the picture he took, did he see what he couldn’t from the field: a little baby eagle head poking out. If I find those sorts of fledglings in my prose, I have to change the light so they can be glimpsed without binoculars.

I’ve always had a quiet voice, but when called for in life I can make it heard, and here and there I’ve got to raise the volume, draw out from the depths I poke with the question of why each scene is there. If there’s a good reason, I have to sometimes make it more apparent, the way I’d pull out a metaphor from an image. With some restraint, but aiming for clarity.

A friend who heard Katherine Paterson speak recently about writing historical fiction told me that she said that she keeps revising until the research doesn’t show. A slogan I’m tattooing on my arm. Or at least using it as a guide. Trying to write in service of the story, making sure every fact or bit of dialogue I keep relates to that, and readers don’t spot the author as researcher trying to smuggle in her cherished findings. I’m cutting, drawing, kneeling on a pad someone gave me for gardening, and scrambling up to add notes on my computer, and sniff the vase of lilacs beside it.

May 4, 2012

Poking Holes in my Manuscript, and Streamlining Transitions

I didn’t mean to suggest my critique group is too harsh when I blogged about coming home from a meeting with instructions to pare a lot and pull out a plot. It’s tough love, yes, but it’s just the kind of love I need, even if I whimper. I send silent thanks as I go through all their thoughtful marks on my manuscript. I just heard a graduating student talk about entering UMass thinking he knew just about all there was to know about literature, then “writing a poetry paper and getting an F … well, actually a B plus.” Yes, I’ve known those students, I’ve been that student, who thinks what she wrote was pretty great, then being reminded we all have a way to go. There are days we get the grade we want, and days we’re sent back to learn some more.

I’ve spent much of this week taking things out from my manuscript and seeing what can be inserted in those holes, if anything. I’m making new transitions, some swifter than before, aided by a wonderful essay called “The Telling That Shows” in The Writer’s Notebook: Craft Essays from Tin House.

Peter Rock writes, “The telling is the voice of the story; the showing is the characters let loose.” and discusses tensions between them, which was fascinating, but for me what was most important was his suggestion that direct telling can be more elegant than floundering through a mishmash of summary and scene for transitions. He quotes several examples from Alice Munroe, such as “A year or so later, Rose was out on the deck.” The idea is to just shift though time and space; it’s not a time for subtlety, tricks, or flowery muddle.

I’m seeing that some of my manuscript’s problems don’t have to do with plot per se, but more with voice: there are places where my character’s sensibility, told in third person, should come across more strongly. Some scenes aren’t necessarily out of place, but distant, and I’m trying to amp up the heartbeat as I let the manuscript feel like mine again. If it moves more swiftly, I’ll thank for critique group for their vision of how I could take it an extra mile, but of course I have to do the work alone. If it’s a bit too weighted with historical detail, it’s a sagginess I’m choosing. For a while it will be me and the manuscript at my desk or on the window seat, enjoying an intimacy I’ll want to change one day.

May 3, 2012

Great Students of Children’s Literature, English 492

There are many reasons to teach, and one of them is hope. I loved reading final projects for Children’s Literature. I’m proud of all twenty-six of my students at UMass, but let me name Danielle, who told me that she didn’t really write poetry when I suggested she try expressing the feelings that she thought a book she read left out. She wrote amazing free verse about a girl dealing with her mother’s death. Sahar had us laughing with a little boy contending with older sisters, one of whom she said was based on herself, and showed a side of her we don’t see in class. I thought a new twist on Red Riding Hood might be impossible, but Jenny, after “staving off my usual fear of drastic rewrites,” proved me wrong. I ask those who choose to do creative projects rather than a final paper to show me at least two drafts, and I was impressed by the way several students developed motivation in their picture books, added surprises, and blended educational elements and fun.

There was great analysis and research, too. In “Life is Just an Imagined Puzzle,” Nicole looked at the ways J. M. Barrie’s Wendy and Lewis Carroll’s Alice make an adventure out of the process of becoming an adult, mixed with excitement and fear, flying or falling, and starting with liberation from adult control. Brenna showed how Dr. Seuss “familiarizes young children with his distinct illustrations and language early, creating a bond with the reader, and later introduces relevant social issues and stories of empowerment, using his signature style.”

Katie taught me a lot about E-books, examining what’s passive and what’s active, what’s similar to reading as most of us grew up knowing it and what’s different. I was interested in her reported research of children learning to read, whose parents might ask over pages questions like, “You’ve done something like that before, right?” or “What do you think will happen next?” but with a device may say, “Careful!” or “Hold it this way.” Kevin is passionate about bringing a broader selection of books into high school classrooms, not substituting Laurie Halse Anderson and Ellen Hopkins for Shakespeare, (though maybe Catcher in the Rye: we can make him cringe just by mentioning that overused title). He wrote, “We do not want to dismantle the bookshelf, but to add to it, to let it grow.”

That’s what we hope. Kenzie examined definitions of childhood and storytelling in Narnia, and quoted C.S. Lewis from On Three Ways of Writing for Children: “surely arrested development consists not in refusing to lose old things but in failing to add new ones.” I hope all of my students move on cherishing the old, and ready for what’s new.

May 1, 2012

One Hundred Pages

Maybe this has happened to you. You’re moving forward through the second half of your third-or-so revision of a novel, feeling pretty happy with your process, thinking you finally got the hang of plot. If you’re a writer, you can see where this story is going. If you’re empathetic, you may be stiffening your shoulders as I did listening to the first person in my writing group go through the requisite but always too short list of things I did right in the first 270 pages. I let out a breath as she calmly said that about 100 pages have to go. And I still need to find a plot.

My two other friends nodded. I nodded, too, trying to hide my gritted teeth. As I eventually packed up three copies of these 270 pages to go out into the cool spring night, I tried not to look like someone who’d been gently told she didn’t get something she’d been trying long and hard to get. I can’t say I slept well. In the morning, I reminded myself that if all three in my writing group think something, they’re usually right. I planned to keep writing toward the end of the novel, taking the good advice of dear Dina to try writing my way back from the climax.

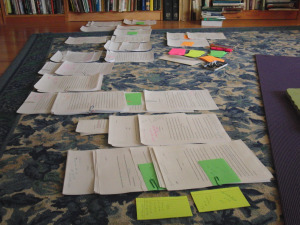

But by the following day, I started a slow, gentle tearing in, going through their good notes, looking at my manuscript, ripping out a sentence here, a paragraph and page there. I was buoyed by the “nices” in some margins. It’s not all bad! A little history can go far, and while I love the texture, it can distract from the line I mean to go through, propelling, well, at least nudging, a reader forward. I’ve made some holes where I’m finding ways to wrestle in and bring out more of my character’s heart, making sure each scene isn’t there just because it’s pretty, but is either a roadblock or slide to a forward movement. So while I’ve got out the scissors, and markers to show myself who appears where, and assess how much I need them, I’m using my pen, too. Adding to the impact of scenes.

I’ve got out the pink and sky blue index cards, and at some point I’ll actually use them, I promise. What does she want? What’s stopping her? I murmur, feeling cheered on by all the you-can-do-its from plot-challenged and history-loving friends posted after I moaned on Facebook. Thank you! I know that faith is in my writing group, too. Now it’s starting to return to me, as with every twist of my blade, every new word, I remember my love for my character. I want her story to be told. And with the new holes, new ideas come, too. My shoulders are almost back where they belong. I’m having some fun again.

April 30, 2012

Betsy Hearne: From Fireplace to Cyberspace: Folklore in Perspective

This past weekend at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, Barbara Elleman, esteemed author, editor, curator, and founder of the museum’s Barbara Elleman Research Library, introduced her longtime friend and former colleague at Book List. Dr. Betsy Hearne has reviewed many, many books, written some impressive titles, and taught at the University of Illinois, all while spending about forty years studying one of her favorite folk tales, which she wrote about in Beauty and the Beast: Visions and Revisions of an Old Tale.

Betsy Hearne spoke of the tale’s roots beyond the familiar French ones, citing retellings of Eros and Psyche and still earlier Sanskrit texts. She discussed new versions and variations, most of which revolve around a father who changes as he gets old, a daughter who matures, and a beast who changes from outsider to be accepted or acclaimed. She mentioned that Beauty is usually at the center, while the beast is often the most riveting in artistic terms.

She sees this as a feminist story, since Beauty saves two relatively passive males, reversing gender roles. “The Beast sets a good table and waits, shows patience and respect for Beauty’s feelings. He’s learned through humbling experience that life without affection is a thorny paradise, even fenced with roses.”

She mentioned how myths have informed her own creative writing: sometimes consciously drawing on folklore for stories about selkies or spells, and sometimes realizing only afterward the influence of myth in work with a contemporary setting. She drew some from some family memories to write the novel Wishes, Kisses, and Pig, but when she’d finished it, realized the influence of tales about wishing on a star and three wishes gone wrong. Her picture book, Seven Brave Women, uses the sort of repetition that makes some folktales memorable.

She ended her talk speaking of the theme of transformation, suggesting how both storytellers and children borrow from different myths, connect the past and present, as all of us make stories. “Metamorphosis of reality begins in the imagination,” she said, ending with a tribute to The Very Hungry Caterpillar, which she called “a test of fortitude ending with new wisdom.”

April 27, 2012

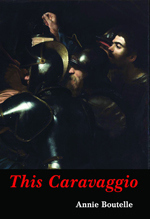

Annie Boutelle Reads This Caravaggio at Smith College

A few nights ago, poet Ellen Watson introduced Annie Boutelle with deep affection, thanking her for founding the Poetry Center as Smith College, now in its fifteenth year. The author of collections including Becoming Bone and Nest of Thistles, Annie Boutelle is retiring after many years teaching, and a warm and grateful crowd had gathered to wish her well and celebrate her newest collection of poems, which Ellen Watson called “elegant, fierce, gorgeous, and spare all at once.”

This Caravaggio, published by Levellers Press, includes reproductions of works that inspired poems that sometimes blend stories of the real models with the Biblical narratives told on canvas, people known in life and imagined in myth. Annie Boutelle gave us a bit of background on the painter who captivated her, telling us that he was born in Milan, but the plague took his father, grandfather and uncle, so he grew up in a house of women. She mentioned his unpredictability, which may have been worsened by the lead white paint which may have entered his body. Some poems feature swords and bloodshed, which we find in the paintings, but Annie mentioned that Caravaggio’s “reverence for ordinary, stumbling human beings, the ones with bare and blackened feet, encourages us to see each as unique and valuable.”

She gave us a glimpse into her research, telling us how she saw a fleshy plant in many paintings, and when she asked a botanist to identify it, was delighted to learn it was mandrake:

“….Clearly my sort of plant. Both

aphrodisiac and sleeping potion,

flagrant as Cleopatra, a known user –“

Language skitters between the formal we might expect of the period, the sort Caravaggio was more apt to use in the streets, as well as in jail, and something modern and direct. Many first person poems speak from the artist’s point of view, while third person poems show us how those who knew him saw him. I’m fond of ekphrastic poetry, but it’s quite something to go beyond a poem composed in response to a painting to read a whole collection based on paintings by one artist.

The spirit of celebration of this giving and daring poet was palpable in the nearly filled hall. Faces glowed as if in Caravaggio’s good light. I took this picture before the reading, knowing I’d leave Wright Hall after dark, but that lamp was still on, and the blossoms a softer white.

For Poetry Friday links, please visit The Opposite of Indifference.