Matthew Carr's Blog, page 3

July 9, 2025

Letters from the Desert

Before I came to the Atacama, I hadn’t looked at stars for a long time. From time to time I saw a few stars through a haze of urban light pollution. But there were never enough of them to hold my attention. Out here in the desert, it’s a different matter.

One night last week, we lay on our backs on wooden palettes outside San Pedro de Atacam, looking up at a sky brimming with stars, while an Indigenous astronomer expertly guided us with a laser pen through the lunar calendar, the motion of the celestial Equator, the location of the Southern Cross, the Diamond Cross, Sagittarius and other constellations that I’d heard of but never actually seen. Afterwards, we looked up through telescopes at the moon, a time-lapse image of a nebula and a galaxy containing millions of stars.

Our guide also talked us through Indigenous ‘dark constellations’ – the great lama and its baby; the fox chasing the baby; the serpent and the toad. We saw the sheen of dust covering the Milky Way, which Indigenous Atacameños regard as a river containing the spirits of their ancestors. As my untrained eye followed our guide’s laser pen, I found myself wondering what else was up there.

I thought of Kurt Waldheim, the war criminal-turned UN General Secretary, whose voice is now circling deep space on the Voyager Golden Record, along with Chuck Berry, Glenn Gould, and the Bavarian State Orchestra. I thought of the Chilean writer Nona Fernández’s remarkable memoir-essay Voyager: Constellations of Memory, in which she links the constellations that she observed in the Atacama to the neurons in her mother's brain, to individual memory and to Chile’s collective memory of dictatorship and the disappeared.

Her book culminates in an account of the Carl Sagan series Cosmos, which she watched as a teenager during the Pinochet years, as she imagines the two Voyagers that Sagan helped prepare, ‘moving through space at this very moment, travelling with their golden records bearing our attempts to register the best of humanity.’

Today, there many objects moving through space that do not necessarily represent the best of humanity. In May 2025, the Union of Concerned Scientists Satellite Database listed about 9,800 active satellites in Earth’s orbit - a figure that rises to 27,000 according the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, if older satellites, rockets and space junk are taken into account. Governments, universities, private corporations such as SpaceX, Starlink, One Web and Amazon are all filling the skies with satellite constellations.

From my desert vantage point, I couldn’t see them, but I knew they were out there: comsats (commercial satellites): Starlink/Netflix combos; military satellites and space shuttles. Some of them were spying and gathering intelligence, or guiding bombs to their target in Gaza or Ukraine. Others would be streaming Better Call Saul or Sex Education, promoting Amazon Prime or GPT Chatbot, or enabling users to post selfies on Instagram.

In the coming decades there are likely to be more and more of them, as the militarisation and commercialisation of space intensifies. But here in the Atacama, there are also organisations that are looking at the stars for entirely different reasons.

Because of its high altitude, dry climate, generally cloudless skies, and lack of light pollution, the Atacama has become the location for some of the most advanced astronomical observatories in the world. Last week, I was lucky enough to visit the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) - the most powerful radio telescope in the world. Established in 2011 and fully-operational since 2013, the observatory is a multinational project involving the European Southern Observatory (ESO), America, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Chile.

The ESO’s stated mission is ‘to enable scientists to discover the secrets of the Universe for the benefit of all’ , and the ALMA is the jewel in the crown of the Atacama’s observatories. In an era in which space is dominated by military and commercial agendas, I was curious to see an international observatory dedicated entirely to the search for humanity’s cosmic origins.

From the main road leading through the Salar de Atacama, we could see the ALMA’s Operation and Support Facility nestled on the slopes of the Andean Cordillera, beneath the Licanbur and Lascar volcanoes. After screening at the entry gate, we drove up the dirt road past the ruins of old Indigenous shepherd hits, towards the offices and hangars - the only part of the observatory visitors are allowed to see.

We couldn’t see the huge radio telescopes on the Chajnantor Plateau, further up, at an altitude of 5,000 metres. There are 66 of these mighty telescopes, which are moved back and forth and clicked into fixed bases, across a distance of 16 kilometres:

These telescopes are moved by giant transportion vehicles with 1,000 horsepower engines, whose drivers - most of whom come from a mining background - need oxygen to work at such high altitudes. Their movements are scheduled months in advance, according to the requirements of scientists across the world, who make use of the facility. The ALMA is essentially a data-collecting centre, which gathers information for others. Every year, proposals are submitted to the observatory and then peer-reviewed, and accepted projects will then determine the movements of the antennae, which will be scheduled months in advance.

This mobility, coupled with the exception e results have often been sensational. It’s antennae have captured images of new-born stars from 500 years ago:

And ‘rotating galaxies’ that existed only 700,000 million years after the Big Bang:

The combination of bandwidth and mobility has enabled the ALMA to take unprecedented high-resolution images, zooming in on planets, stars, and galaxies in the ‘cold universe’ that are invisible to the naked eye. As a result, the ALMA has become both a cosmic narrator and ‘time machine’, piecing together and reshaping our understanding of the earliest stages of the Universe. These achievements have enormous scientific value, but to what extent does the ALMA contribute to ‘the benefit of all?’

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I asked our guide Nicolas Lira, the ALMA’s Education and Public Outreach Coordinator. Lira has been working for ALMA for twelve years now. An eloquent and thoughtful former journalist, he has a background in physics and science and used to work in the tourist industry, television newsrooms. None of this suited him. ‘ I started to seek some purpose, where I could combine my skills, and I found a home here, combining science and science communication skills, and working for humanity and not for profit.’ I asked him how ALMA’s work benefited humanity.

We are trying to explain how life came to be in our universe, because everybody has these fundamental questions: about how we came to be on earth, about how we came to be alive, and what will happen to civilisations in the future. Of course the timescales are so big that it might not seem important for a single life, but I think what differentiates humans from other species is that we actually ask ourselves these questions, and we can actually project ourselves into the future and into the past.

But how would he explain the significance of these discoveries to the lay person?

If you want to improve life or how to understand life, you have to understand the origin of what can sustain life. And that cannot be done without astronomy. Or course, neither can it be done without biology or a fundamental science. But astronomy is one of the buildings blocks of that knowledge.

Given the shortness of a human life, was it really possible for ordinary people to comprehend the significance of astronomical discoveries that ranged back and forth across unimaginable timescales? Again, Lira had an answer:

Most people are able to understand that we are a small part of a very big universe. That’s what makes us look at the sky or at the ocean, and whenever you look at the moon you see the vastness you do feel that you are something small in something very big. And humanity has been trying to build a heritage over the centuries, over millennia. When we started writing on walls, 30,000 or 3,000 years ago, that was the beginning of building a heritage. So I think most people do have a sense of making a small contribution to a bigger heritage.

Though Lira pointed out that this sense of contributing to a heritage was not limited to astronomy, he nevertheless insisted that astronomers occupied a unique and privileged position that enabled them to ‘take a picture of the universe, so complete and so detailed that it will allow humanity to guess how it was before and how it was going to be afterwards.‘

These were fine words, and as Lira showed us round the laboratories and control rooms where data from the radio-telescopes was collected, 24 hours of every day, I was impressed by the technical expertise that had been directed to what was essential an altruistic exercise in pure science: It was a thrilling and awe-inspiring sight to see one of the antennae, some thirty foot high, next to its transportation carrier:

This was technology at the cutting edge, with no military or commercial implications. In a world increasingly governed by yahoos, it was a testament to the benign possibilities of international scientific cooperation. As we drove away, I thought of Johannes Kepler, the seventeenth century astronomer, and mathematician who discovered the laws of planetary motion.

Kepler’s personal and professional life was marked by tragedy, financial insecurity and constant setbacks and reversals. He lost three children before the age of six within a six-month period. His first wife died of fever in 1611. He lost three more children with his second wife Susannah, who also died young.

He was financially dependent on various patrons, and subject to the shifting winds of religious intolerance. He lived in an age of violence and fanaticism – against a background of imperial conflict and the barbarism of the Thirty Years War. His mother was put on trial for witchcraft - in part because of a reference to a herbalist in his ‘science fiction’ novel Somnium.

And yet Kepler never stopped looking at the stars, and studying the cosmos that be believed had been created by God. Our technology-saturated age is also an age of violence, religious fanaticism, moronic quasi-religious superstitions pumping endlessly through a supposedly interconnected world, that continues to generate polarisation, conflict and division.

Where Kepler’s peers once tried his mother for witchcraft, tens of thousands of people in the 21st century believe that viruses are carried by 5G, that the world is governed by cannibal celebrity-elites. We live in an age in which men run down pedestrians in the name of God, and target abortion clinics that they believe are the work of the devil. The day before I lay in the desert looking up at the stars, Israel obliterated a café in Gaza with a 500 lb bomb - guided by satellite.

The ALMA belongs to a different world, and to different possibilities, that are still present even in our new age of barbarism and our wilful embrace of malevolent stupidity. From the world’s driest desert, it is probing the spaces between the stars in an attempt to tell humanity where it came from and where it might be going. As I returned to San Pedro de Atacama, I felt privileged to have seen it. And I took some consolation from the endless reminders of our fractured and increasingly demented world, in the knowledge that Kepler’s heirs were using this mighty outpost of science in the Andes ‘for the benefit of all.’

July 6, 2025

Letters from the Desert

From Cormac McCarthy’s The Road to the Mad Max franchise, deserts are ubiquitous components of our worst imagined future - the barren lands where civilisation dies and feral bands engage in violent competition for scant resources, almost none of which come from the desert itself.

Deserts lend themselves easily to these fictional scenarios, because deserts have long been imagined by outsiders as dead lands that are unfit for humans. But the Atacama has other stories to tell, and I was keen to hear them.

Before coming here, I was intrigued by the atrapanieblas (fogcatchers) - a Chilean invention which uses Raschel mesh to ‘catch’ fog moisture and turn it into water. This mesh is commonly used in athletics and sports wear, and agricultural packaging. The Chilean variant uses vertical panels, stretched out like hides between two tall pillars, to trap the moisture from the fog known as the Camanchaca , which drifts in most days from the Pacific Ocean along some 1,200 kilometres of coastline.

I wanted to see how this technology worked in practice, but my attempt to do so turned out very differently to what I expected - a near-disaster, followed by an experience of the desert that I won’t easily forget.

The day began in Iquique, when I sent a request to the Universidad Católica del Norte, asking to visit the UC Atacama Desert Station at Alto Patache, where one of Chile’s ‘fog oases’ were located. I had applied before, without much luck, and nothing seemed to be happening this time, so I went off to the famous Zofri shopping mall, basically because I had never seen a shopping mall in a desert before.

Iquique is one of the largest duty-free ports in South America, and the docks were stacked with containers some seven stories high, alongside a garish Macworld mall containing all the commodities that you would expect to find anywhere - except that some of the mobile phones and computers would have been made with components extracted from the desert itself.

Shortly after that, I got a surprise call from Milton Aviles, the station manager at the Alto Patache station, to say that the station’s director in Santiago had given me permission to spend the night there.

I immediately accepted. Jane was ill with a cold, so I went alone. Around 8 o’clock, Milton and his mate Jorge picked me up. We drove south for about 45 miles along the notoriously accident-prone coastal road from Iquique to Antofagasta, before turning eastwards along the ‘salt route’ that connects the Salar Grande salt mine to the Puerto de Patillos.

To see these giant trucks laden with salt, moving down to the coast, while empty trucks headed up to the mine from the opposite direction to fill up, was to bear witness to Chile’s gargantuan extractive operations in the Atacama, and the 24/7 supply lines that connect the desert to the most far-flung ports with relentless precision. After about half an hour, we left the road and drove along a bone-crunching service road that followed the direction of an electricity pylon.

Finally, I made out a cluster of geodesic domes in the darkness. When we got out, a cold wind was whipping through the compound. I could see the Milky Way above my head, but not much else. It could not have been more different from the fluorescent consumer dreamworld of the Zofri mall. This station had been built in 2016, to replace the previous one that had been destroyed by flash floods the previous year.

I was thrilled and disoriented in equal measure, as Milton turned on some electric lights that dimly illuminated the domes and the wooden walkway that connected them. It felt as if I had arrived on Mars, but I had hardly installed myself in one of the domes when I missed my step and fell off the walkway, cracking my forehead on the corner of a nearby bench. Milton was distraught, thinking that I might have concussion, and he had reason to worry. The bench had caught my forehead just above my right eyelid - an inch or two lower and it would have probably crushed the eye.

My first reaction was intense disappointment that I might not see the station the next day. Blood was seeping through my fingers, and I was minded to patch up the cut with a homemade butterfly stitch and tough it out, but when I looked in the mirror I saw the cut was deeper than I thought. So Milton kindly drove me to a polyclinic about half an hour away down the salt route.

Once again we set out into the dark, and veered in and out of the growling trucks. When we got to the clinic, the paramedic gave me the usual tests. I was still dazed from shock and adrenaline, and he made me lie down and asked me what was needed to become a writer. Why would anyone want to do such a thing? He asked, in a concerned, and faintly pityingly tone.

He had a point. But as I lay there with a makeshift plaster on my throbbing head, I tried to defend my chosen profession and explain the qualities required. Surely he must have some stories he would have liked to write about? I asked, hoping to end the interrogation.

He did, and he proceeded to regale me with some tales of unbelievable carnage and tragedy drawn from his long career pulling people from crashed cars and motorbikes along the Iquique-Antofagasta highway. It was almost a relief when he finally told me that I would need stitches, and that we would have to go to Iquique to get them.

So the noble Milton drove me all the way back to Iquique, where a doctor named Doctor Alegre ( Doctor Happy - and no, I’m not making this up) gave me two stitches and sent me on my way at about 4 in the morning. Once again we headed down the highway of death, up the salt route, and onto the dirt road leading into the howling void. Finally, I got a few hours parody of sleep, huddled on a camp bed with the desert winds tugging at the dome.

The next morning, I woke up and looked around at Alto Patache station, and it all seemed worth it. Because this was the desert in all its raw, majestic splendour. From the compound, I could see banks of low cumulus clouds being pushed out to sea by the wind. By mid-afternoon, Milton confidently assured me, the winds would reverse direction, the Camanchaca would descend on the hillside, and the fogcatchers would begin to work their magic.

I left Milton and Jorge assembling another geodesic dome, and walked up the path to the greenhouse and the two largest fogcatchers. I don’t know if it was the blow to my head or the sleeplessness, but I felt exhilarated and even euphoric. To the east, the dry hills stretched out endlessly, and I could see dried up river beds, ancient llama trails, and paleo-runoffs etched like scratch marks into the dry slopes.

At first sight, the terrain seemed utterly barren. But then I saw patches of orange, green and yellow from a distance, and moving closer I could see lichens clinging to the rocks, occasional shrubs, and little pieces of black silicate rock that might have been left by meteorites.

This was not the barren land of The Road or Furiosa. All around me, living organisms had found enough moisture to cling tenaciously to the rocks and dry stony earth, and it was this unlikely capacity for survival that has inspired the UC Desert station and other similar experiments in the Atacama and beyond.

In a hyper-arid region where there is rarely enough rainfall to support human life, Chilean scientists have learned how to extract moisture from the camanchaca fog, which settles for some 1,200 miles of coastline. Fog moisture is not heavy enough to fall to earth and become rain, but scientists saw that lichens and cacti were able to ‘catch’ enough liquid to enable them to survival, and fogcatching technology sought to do the same for humans.

The invention is ingenious and also very simple. Mesh panels are fixed into the upper slopes of the station, which trap moisture as the fog passes through them. These microscopic droplets fall into a plastic gutter, and drain into hosepipes, which connect storage cisterns. When the water in these tanks reaches a certain level, it is transported by high-pressure hose pipes into the station’s sink, showers, and toilets.

Amazingly, this system produces an average of 45,000 litres of water annually - enough to sustain the station and its visitors throughout the year. The water also enables a cactus garden, a greenhouse filled with strawberries, lettuce, tomatoes and herbs, and a small plot of maize. Electricity is provided by solar power, which makes the station - potentially - entirely sustainable.

I felt strangely moved by this experiment, as I stood listening to the wind ‘singing’ through the mesh on the largest fogcatcher. I walked around, examining lichens, past the small fogcatchers, the seismograph that measures tremors and earthquakes, and the meteorological station measuring humidity, temperature, and radiation levels. I saw the ‘art in the desert’ house created by the Catholic University’s architects - the prototype for a sustainable habitation in extreme environments that eventually became a larger house presented at this year’s Venice Biennale of Architecture.

At the end of my walk, I stood on the cliff overlooking the salt port at Puerto de , .and the nearby copper port. Further south, I could see the Pabellón de Pica, graveyard of so many Chinese workers who were tricked into slavery to work in the lethal guano industry that provided fertiliser for European and American farmers in the nineteenth century.

Incredibly, it was only 20 years ago - following intervention from the Chinese government- that the remains of Chinese workers who had been left to dangle from the ropes for more than 150 years where they died were finally taken down and given a decent burial.

From guano to copper and salt, this was the history of the Atacama: the ruthless extraction of minerals and metals, from nitrates, silver, copper, and lithium, that have decisively shaped the modern world. The Alto Patache station told another story - a little marvel of human adaptability with implications for Chile and beyond.

At one point in my wanderings, I came across a large bush that seemed to owe its existence entirely to the fogcatching cistern alongside it. Rising up out of the stony ground at a height off nearly four feet, it seemed nothing short of miraculous.

But there is no miracle here - just scientists using their intelligence and knowledge to solve local problems that are also global problems. This is why Carlos Espinosa, the Chilean scientist who first invented fogcatchers in the 1950s to address the problem of water scarcity in Antofagasta, donated his patent to UNESCO, so that others could use it. The Alto Patache station has been instrumental in creating the AMARU (water snake in Quechua) ‘Fog Catcher Map’ which uses data from the 25 stations of the Chile Fog Water Monitoring Network.

As Milton told me, fogcatching is not a catch-all solution to hyper-arid spaces. Not every desert has the regular fogs that descend on coastal Chile, or the coastal cordillera that prevent them from dissipating, and the winds that push the camanchaca into the traps. But in demonstrating human adaptation to an environment that is generally considered to be unsuited for human habitation, it also offers a relatively low-tech micro-solution that could potentially be applied to other countries with similar conditions.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

In the years to come, we will need this kind of ingenuity and creativity, and altruistic science. Last week the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) delivered another of its increasingly grim warnings on global desertification and drought. Coming in a summer when even Europe is sweltering under record-breaking temperatures, the report was further confirmation that desertification is part of our present and future.

By the late afternoon, the Camachaca had not appeared, and I was amazed to count four drops of rain on my face and hands. Milton and Jorge eyed the clouds gloomily, and said that there would be more where that came from.

It didn’t seem likely, but as I drove back to Iquique, I felt encouraged and hopeful by what I had seen. In the future we will need the fogcatchers far more than we will need Mad Max and Bartertown. In a world facing ecological catastrophe, we will need people looking for practical, accessible solutions to natural problems and the problems that humans, and not for profit or glory, or the benefit of shareholders, but to help others.

As we approached my hotel, a man dressed as Predator was pretending to attack passing cars. It seemed a fitting end to my wild ride into the desert. Once again, I thanked Milton, who had done so much to help me. And as I walked into the hotel lobby, the privilege of seeing this experiment with my own eyes was well worth the crack on the head.

Milton and Jorge were right, of course. That night it rained in Iquique, Alto Patache and in other parts of the Atacama. Such events do happen from time to time, but they are never enough to make a long term difference.

This is why the fogcatchers are needed. And in the years to come, many Chileans in the north will be keen to see how Amaru the water snake wends its way up and down the coast, and other communities around the world may also have reason to see how this experiment unfolds.

All photographs taken with permission of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Norte.

July 3, 2025

Letters from the Desert

Pisagua doesn’t feature in many tourist itineraries of the Atacama. Few non-Chileans have even heard of it. But for many Chileans, Pisagua has very particular associations. There was a time when soccer fans who disliked certain referees chanted ‘send him to Pisagua’, and parents would terrify their wayward children by threatening to send them there.

This spooky reputation is partly due to Pisagua’s remoteness. Pisagua lies some 1,200 miles from Santiago on the edge of the Atacama desert, and is still difficult to reach.

We had to hire a driver to take us there, who drove some 101 miles along the Pan-American highway from Iquique, before turning off onto the lonely, twisting road that leads down from the coastal cordillera. The only sign of human habitation in the barren, desolate hills was a humble wooden cemetery where Chinese slaves who once worked on the nineteenth century guano trade were buried.

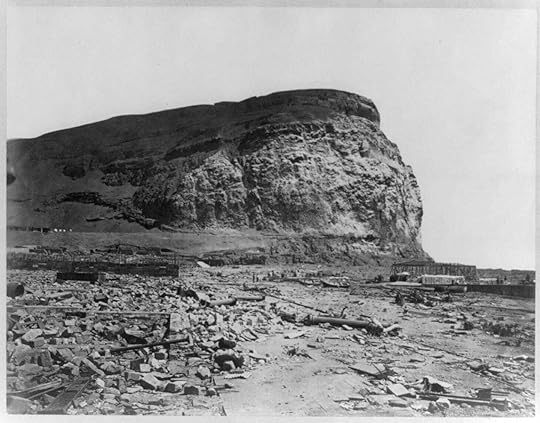

After about twenty minutes, Pisagua appeared below us, flanked by looming cliffs that enhanced its gloomy end-of-the-world isolation.

In other countries, this beautiful sheltered bay might have attracted divers and a niche touristic destination, and Pisagua wasn’t always as remote as it is now. During the 1890-1914 nitrate boom, the town was one of Chile’s top three ports, with a population of 26,000. At that time it boasted an elegant wooden hospital, banks, commercial houses, hotels, and a highly-rated theatre that entertained the crews and passengers of clipper ships that queued up in the little bay to transport nitrate to European and American ports.

Today, those glory days are long gone, and some 300 people eke out a living from fishing or collecting algae, amongst the dilapidated houses, shacks, and ruined public buildings. The hospital, the railway station, and most of its public buildings have been reduced to hollow shells.

Anywhere else but the Atacama, Pisagua’s wooden buildings would have rotted away and collapsed a long time ago, but here the imported Oregon-pine facades still bear witness to the decline of a once-great industry that, in Pisagua at least, has never found a replacement.

Like the Atacama’s other coastal towns, Pisagua is prone to earthquakes, tsunamis and plagues; outbreaks of bubonic plague and yellow fever decimated the population on successive occasions before World War I. In 1828 and 1868, earthquakes destroyed the town. Because so many of its buildings were built from imported wood, it was also susceptible to fires. In April 1879, a Chilean naval bombardment burned much of it down during the War of the Pacific. On 2 November, the Chilean military carried out the first amphibian assault in modern history, and took the town from its Peruvian/Bolivian defenders.

In 1905 another fire caused equal levels of devastation. Despite these periodic disasters, it wasn’t until the decline of the nitrate trade in the 1930s, that the town fell into terminal disrepair from which it has never recovered. And it was in this period that Pisagua began to acquire the sinister reputation that led our driver to reflect on its ‘bad vibrations.’

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Because of its geographical isolation, Pisagua’s abandoned buildings and prison have repeatedly provided successive authoritarian governments with a detention centre/concentration camp for political prisoners and other undesirables. In 1942, it was used to detain homosexuals and other ‘socially maladjusted’ individuals. During the 1940s and early 1950s, communists were imprisoned there.

Augusto Pinochet served there in this period as a young officer, and once tried to prevent Salvador Allende - then a senator in the Chilean north - from inspecting the facilities where these prisoners were kept. When Pinochet let the coup that overthrew Allende in 1973, Pisagua became a detention camp once again, where the army imprisoned, tortured and killed Allende’s supporters.

According to the 1990 Chilean Truth and Reconciliation Commission, detainees were interrogated, beaten and given electric shocks, forced to do hard labour, perform exhausting physical exercises, such as trying to climb ladders while soldiers attempted to push them over. Others were forced to lie on the ground in the cold or heat for 48-hour periods, and women prisoners were also subjected to sexual violence.

The Chilean historian Karelia Cerda has described Pisagua as a key to the consolidation of the Pinochet regime’s power in northern Chile, where psychological and physical violence was inflicted on some 800 prisoners - the better to terrorise the wider population and annihilate the political generation that brought Allende to power.

The military authorities who ran the Pisagua camp also carried out summary executions and forced disappearances. In 1973 and 1974, some prisoners were sentenced to death by summary court martial. Others were supposedly shot trying to escape. The Chilean Truth and Reconciliation Commission dismissed the legal legitimacy of these courts and also rejected the notion that prisoners had tried to escape.

Any visitor to Pisagua will see that it is virtually impossible to escape from. The open grave you see below once contained the bodies of 21 men, including Ariel Dorfman’s boyhood friend, the young socialist leader Freddy Tavernas, whose bodies were excavated in 1990. Other prisoners killed at Pisagua have never been found.

Today, a memorial marks the spot, with a quotation from Pablo Neruda, above the beach that Chilean soldiers once stormed in 1879.

Only a few dozen yards from the grave, the Chilean military has its own monument to the 1879 landings, and rows of wooden cemeteries mark the graves of Chilean, Peruvian and Bolivian soldiers who died that day.

This is a lot of history for even a large town to bear. Every year, leftist delegations, including former prisoners and their relatives, come to this spot to pay homage to the victims, as part of an ongoing process of historical remembrance. And every year the Chilean army stages a commemorative event on the anniversary of the 1879 landings. Individual former detainees also return periodically to Pisagua. Some come to remember former comrades or seek some psychological release. Families of disappeared prisoners occasionally carry out exhumations, in search of the remains of executed relatives who the military has taken responsibility for.

Only two weeks before our visit, according to local guides Marcia and Camila, a retired soldier who had served in Pisagua during the Pinochet years, had returned to the town, to ask the Virgin Mary forgiveness for having stolen money from the church collection box, to buy a can of tuna fish to appease his hunger.

It was bewildering and disorientating to contemplate the physical traces of so many tragic histories. During the Pinochet dictatorship, detainees were kept in the former market, the prison and also in the illustrious theatre where, it was said, the ‘Divine Sarah’ Bernhardt may once have performed. According to one of our guides, the military forced prisoners to take part in obligatory theatrical ‘competitions’ which the ‘losers’ were punished with death.

Today, the theatre is still used periodically, as part of ‘Project Pisagua’ - an attempt by local and regional campaigners to give Pisagua a viable future. For now, the town remains trapped by its grim past. In one of the balconies of the eerie but still recognisably splendid theatre, bald mannequins of former ‘English’ patrons from the nitrate years looked towards the stage, their hands frozen in applause.

Someone had stolen their wigs, and they sat frozen in the gloom, like ghastly apparitions from a film that Adam Curtis might have made. As I turned to leave the theatre, I passed another mannequin of a grinning clown-soldier, that had fallen out of a cupboard.

If history, to paraphrase James Joyce, was a nightmare from which we are all trying to awake, then Pisagua was a microcosm of Chile’s own passage through the sewers of Cold War history. But this history is also part of our history. The regime that turned this town into a prison-cum-death camp was an ally of the United States and Britain. General Pinochet was a personal friend of Margaret Thatcher. Her government borrowed heavily from his economic program. He escaped trial because of the cowardice and collusion of the Blair government.

The men and women his soldiers killed and tortured were guilty of the audacity of wanting a more equal society, and believed that they could achieve through a peaceful democratic process.

The coup shattered that dream. And Pisagua’s House of Horrors, was part of the nightmare that followed. Today the world is stalked by political forces that are just as capable of the cruelty and violence cruelty that Margaret Thatcher’s favourite general inflicted on the Chilean left, in Pisagua and in many other places. Like the boy in a mural that I noticed as we left, humanity is increasingly alone and adrift on a stormy political sea with no harbour in sight.

Pisagua is the town that history swallowed and spat out, and yet still there are people like our valiant guides Marcia and Camilla, who refuse to let it die, and are seeking to build a future from its ruins.

And when I think of Pisagua, I think of them. And perhaps those of us who will never go to Pisagua, should think not just of the torturers and executioners who turned this outpost of Chilean Siberia into yet another Cold War theatre of cruelty.

They should also think of the men and women they tormented and killed, and imagine them living, breathing, talking, and dreaming of a world that is still out there, waiting to be built.

June 30, 2025

Letters from the Desert

In my last letter, I described the Atacama Desert as a repository of memory; a blank canvas, on which the names of the dead have been written in order to ensure that their names are not forgotten. These aspirations are not limited to individuals. Drive nine miles from the city of Calama, through the rubbish-strewn desert and the forest of whirling wind turbines that line the road to San Pedro de Atacama, and you will notice a tall white cross protruding from the entrance to a circle of twenty-six round pink pillars.

It isn’t till your drive off the road leading to this ‘Park for the Preservation of Historical Memory’, that you realise how large and imposing it is. The monument was inaugurated in 2004, at the same place where the remains of 26 political prisoners murdered by the Chilean army in October 1973, were found 19 years later in 1992.

We visited the monument yesterday evening, and descended the steps to the circle of bare earth baring flowers and tributes to the men whose remains were found in this same spot. At the centre of the circle, a brass plaque from the Group of Family Members of the Politically Executed and Disappeared Detainees’ (AFEDDEP) of Calama paid tribute to the 26 men who had been buried in ‘the dry soil of Atacama’ in this same spot. The monument lalso recalled the relatives of the victims who had engaged in a ‘long search through the desert that is still not over.’

The monument - and the time cycles it incorporates - marks one of the most notorious crimes carried out by the Pinochet dictatorship, and it’s also a testament to the long struggle for recognition and justice waged by a group of women from Calama, and one woman in particular: Violeta del Rosario Berríos.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I first heard of Violeta nearly seventeen years ago, in Patricio Guzmán’s great film about the Atacama Desert, Nostalgia for the Light. Until then, I knew nothing of the women of Calama, who had spent decades searching through the desert for bone fragments of their husbands, sons and brothers who were murdered by the Pinochet dictatorship in 1973.

Naturally, the dictatorship never admitted to these crimes, nor did it tell the relatives of its victims where the bodies of their loved ones could be found. Because, like the other military regimes that seized control of the southern cone countries in the early 70s , the Pinochet dictatorship was cunning, cowardly and cruel in equal measure. In granting itself impunity for whatever crimes it felt the need to carry out in the name of anti-communism and ‘national security’, the regime frequently resorted to the sinister tactic of ‘forced disappearance’, and the Atacama was one of the regions of Chile where these bodies were dumped.

When I saw Gúzman’s film, I was shocked and moved by what seemed like some awful Greek torment - a terrible exercise in futile suffering that Odysseus might have inflicted on the Trojan women.

In the film, Gúzman lets Violeta Berríos do most of the talking. At one point, she delivers a heartfelt monologue to camera in the middle of the desert that is one of the rawest and most searing expressions of grief and loss that has ever appeared on a cinema screen. Gúzman’s film was made in 2010, and Violeta’s face is a mask of agonised intensity, leathered and lined by the decades that she had spent combing the desert in search of her husband’s remains.

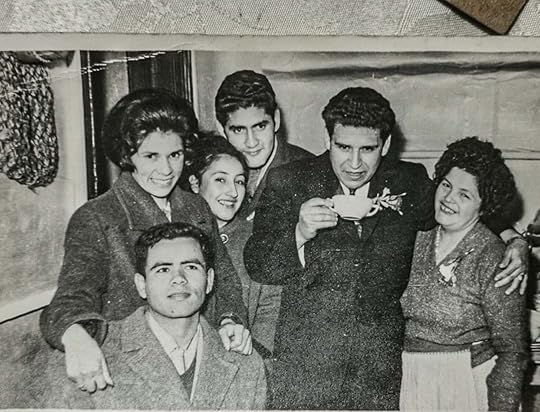

The day before my visit to the monument, I visited Violeta in her little house in the mining town of Calama. She is now 87, frail, slow-moving, and clearly in poor health, as she came to the gate in her dressing gown and slippers, and shushed the two rowdy dogs that she calls her ‘daughters.’ This is the same house that she once shared with her husband Mario Arguelles Toro, a taxi-driver and local Socialist Party member in Calama. In the photograph below, she can be seen in the left, standing with her hands on his shoulders.

At that time, Violeta ‘knew nothing about anything’, as she puts it, and lived a peaceful domestic life with her idealistic husband. That world came crashing down on 19 October 1973, when a special unit which later became known as the ‘Caravan of Death’ arrived in Calama in a Puma helicopter, to carry out the last phase of a campaign of murder and extrajudicial executions which would ultimately leave 75 people dead in the Chilean north. This unit was lead by General Sergio Arellano Stark, a fanatical anti-communist and close confidant of Pinochet, and effectively acted as a state-sanctioned death squad, killing prisoners who had already been sentenced to imprisonment on trumped-up charges relating to their political affiliations to Allende’s Popular Unity movement.

Before Arellano’s arrival, many of these prisoners believed that they were about to be sent to concentration camps in the south. Arellano’s unit had other ideas. Because of Calama’s connections to the copper industry and the Chuiquicamata mine, the city was considered to strategically important to the regime and singled out for a special dose of exemplary terror.

Overruling or imposing his own mandate on local commanders, Arellano’ unit had already established spurious ‘war councils’ across the north, that sentenced prisoners to death merely for membership of the Communist or Socialist parties, and it proceeded to do the same in Calama.

Such behaviour shocked even the commanders who had arrested these prisoners in the first place. The commanding officer who received Arellano’s men in Calama with a marching band and an honour guard, was shocked to find the general’s unit draped with cartridge belts and carrying machine guns in a state of combat readiness. Arellano immediately called a war council, and his men set about beating the prisoners and selected names for execution. By the end of the night, 26 men had been shot and cut to pieces with sabres, and buried in the desert.

One of them was Violeta’s husband Mario. And his murder plunged her into a political nightmare that has never really ended. In November 1973, she joined the Socialist Party. That same month, she joined the Chilean Commission of Human Rights, beginning a long trajectory as a human rights campaigner, which has earned her both national and international recognition. Violeta was a founder member of AFEDDEP, which lobbied successive Chilean governments to find the remains of their loved ones, and bring those responsible to justice.

Year after year, week in, week out, Violeta and the women of AFEDDEP combed the desert in search of their disappeared relatives. Supporting herself as a cleaner, Violeta and her compańeras went out into the desert whenever they could. They began their search at a time when the Pinochet regime was at its most savage and dangerous, and they continued to search throughout the dictatorship years and beyond. It was not until July 1990 that the women of Calama were directed to a mass grave containing the remains of 24 of the 26, including a single bone that belonged to Violeta’s husband.

This was not the original spot where the men had been shot. Like its counterparts in Argentina, the dictatorship constantly tried to cover its tracks, and so the 26 had already been dug up and reburied in the spot where they were found - a process which further destroyed their remains. After years of searching, Violeta and her companions were shocked to find that the remains of their menfolk had been buried only a hundred yards from the main road.

Even then, the women continued their search, because, as Violeta once said, they wanted more than a single bone fragment, and also because the grave contained the remains of only 24 of the original 26. In 2008, Arellano Stark was sentenced to six years in prison for his role in the Caravan of Death - a mockery of justice that he escaped on grounds of dementia. He died in 2016, without serving time.

The Eternal Walker in the DesertToday, the woman who once described herself as an ‘eternal walker in the desert’ is not longer able to scour the Atacama, but she has never really left the desert. Some years ago she told an interview that she had ‘no life beyond the search. ’ I asked her if she still felt like that. ‘No,’ she replied. ‘ Because I realise what the doctors once told me a long time ago, that these are the consequences of everything that happened. They said that you have to cut this cord and live the little life that remains to you. But I live here alone with my dogs and cat. I live mentally in the desert. The desert is always here in my home.’

Had she never felt any temptation to abandon the search or give it up during those years? ‘When I reached sixty,’ she said, ‘I didn’t realise that thirty years had passed. I didn’t notice it. It’s cost me so much effort to come to terms with this, because those thirty years - did I live them? I don’t know how I lived them. The only thing that existed was the desert.’

For some people, who had not undergone the experience of forced disappearance, I suggested, such tenacity would be difficult to comprehend. Where did she think it came from? ‘Honestly, I don’t know,’ she replied. ‘You can’t tell where it comes from. One day we began to go out searching and that’s how we found ourselves. But I can’t explain to myself where it comes from, this desire to have some trace, to find something, even when I never thought I’d find even a rib.’

Violeta still has very clear memories of the husband she lost. She described Mario as a ‘calm man who was very easy to talk to’, and remembers he and his friends trying to ‘put the world to rights’, and discussing political issues that she had no interest in at the time. When I asked her why she joined the Socialist Party only a month after his death, she said that she simply wanted to ‘keep his flag flying.’

Perhaps not surprisingly, after everything she has gone through, she now declares herself to be ‘disillusioned with politics and everything’ in her own country, and is pessimistic about the impact of her years of campaigning on present-day Chileans. She listed some of the massacres and crimes carried out by the Chilean army in the past, and clearly saw the potential for their repetition in the future. ‘We Chileans have a very short memory,’ she said. ‘We don’t look back too far. So I hope that none will ever have to go through what we experienced. To read about it is so much easier than living it. You would not want anyone to go through a situation like this, to search for a man, your brother, your husband.’

I agreed. And as I sat in the living room of this brave, exhausted woman, I imagined Mario talking to his friends about putting the world to rights, when he and so many other Chileans believed they had discovered a democratic path to socialism. I thought of the proud, happy, smiling woman in that youthful photograph, and imagined the life Violeta might have had, if her husband had not held those beliefs. Perhaps Mario would have grown old with her, living in that house with their dogs and cat, visited by their children and grandchildren.

Instead, their lives had been wrecked by fascism, and the cruel barbarities of twentieth century politics. It was easy to see Violeta and her friends as victims, driven by a grief that was close to madness as they combed the desert for the remains of their loved ones.

But what I saw in the gaunt, shrunken woman beside me was an astonishing courage that led her to challenge a state that had turned serial killer and murdered the citizens it was pledged to protect; a deep, unshakeable devotion that refused to allow the man she had loved to be erased from the earth, and a powerful bond of solidarity that connected her to the other women of Calama, when others might have walked away.

Joan Baez once said of the Mothers of the Playa de Mayo, that the human race would have disappeared centuries ago had it not been for women like them. The same could be said of Violeta and the other eternal walkers in the desert. When our conversation was over, she gave me a badge from AFEDDEP Calama, which read, ‘If I am in your memory, I am part of history.’

As I left, I hugged her, and holding her delicate, fragile body in my arms, I murmured that it was a privilege and an honour to have met her, because it was. And stepping out into the sunlight to catch a taxi, I knew that she would always be in my memory, but I wished she, and so many others, had been part of a different kind of history.

June 27, 2025

Letters from the Desert

Six days ago, while I was in Iquique, the philosopher Helen de Cruz died in the United States, from a long illness which her friends and Facebook friends were familiar with as a result of her Facebook posts. I knew Helen only as a Facebook friend. We came into contact in the immediate post-Brexit period, through the One Day Without Us campaign. Helen was one of many Europeans who had their hearts broken as a result of Brexit, and left the UK to take up a new post as chair of philosophy at Saint Louis University.

We followed each other, and sometimes commented on each other’s posts. In addition to her work as a philosopher, she was a talented artist, a writer of short stories, speculative fiction and novels, and a student of the lute. Knowing that I liked John Dowland, she would sometimes tag me in posts showing her playing some of Dowland’s pieces. I understood that she was a special person. I remember when her book Wonderstruck came out - I don’t remember the exact words - that she expressed her desire to write a book about the importance of wonder in life, in order to combat the evil that was coursing through the world at the moment.

An admirable desire, and Helen clearly had so much more that she wanted to accomplish. When she began to discuss her illness on Facebook, I was impressed by the honesty, lucidity and that she brought to her predicament. She railed against the unfairness of it - dying in her late forties when she still had so many things she wanted to do, people and things she wanted to see, and books she wanted to write. I sometimes wondered, reading her terrifying accounts of grappling with the US health system (doctors on the phone haggling with insurance companies over painkilling drugs etc), whether she was an indirect victim of Brexit.

I can only speculate about that. What I do know, is that at a time when so many people who bring evil into the world live far longer than the world needs them to, is that the world lost someone very special when it lost Helen. But this is the thing about death - it doesn’t have any moral criteria. People will die young and they will die old, and more often than not, except in the case of a preventable tragedy, there is no sense to it, and no reason for it.

The Chinchorro people knew this, 7,000 years ago, when they first began to preserve even the youngest members of their society, who had been inexplicably taken from them. I had just left Arica, when I read of Helen’s death in a family post, which poignantly expressed her overriding wish: to be remembered. I’m sure she will be, by those who knew and loved her, and also by the people who came into contact with her through her work, and through her posts on Facebook - a medium that she hated but still used.

But for most people, the brutal but inescapable fact of life is this: that when you die very little of what you saw, felt and heard during your brief time on earth will be remembered for long. Like my great grandparents, and the wider constellations of aunts and uncles connected to my parents’ families, most of us will have vanished or faded so far into the past that no one will remember our names. This knowledge can be a hard thing to bear, and human beings - regardless of the cognitive powers of elephants - are the only ones who have to bear it.

Why is it so hard? Because it’s lonely to think that we are born and then we die, and that’s it. Some of us find solace in religion - not my case I’m afraid. Others seek power on earth in order to create their ‘legacies’ - no matter how detestable. And many of us just hope our children and our grandchildren will carry some visible trace of who we were.

This question of memory was one of the reasons why I came to the Atacama, and also why I was intrigued by Chinchorro culture. Because even before I saw them, those mummies, buried on beaches thousands of years ago by a people with no literary culture, seemed to me to be a particularly poignant and moving expression of that elemental universal human desire: to leave something of ourselves behind, and let the world know that at one point in time, we were actually here, and that the people we have lost were actually here.

At the same time, these aspirations are often at odds with the limitations of individual and societal memory. During the flight to Santiago I read Jorge Luis Borges’s marvellous story ‘Funes the Memorious.’ In it, the narrator tells the story of an Uruguayan acquaintance named Ireneo Funes who has the ability of total recall. Unlike the narrator, Funes can remember everything he has ever seen, thought, felt or read. This mysterious ability is the result of a horse-riding accident, which paralyses him:

He told me that before that rainy afternoon when the blue-grey horse threw him, he had been what all humans are: blind, deaf, addle-brained, absent-minded…For nineteen years he had lived as one in a dream: he looked without seeing, listened without hearing, forgetting everything, almost everything. When he fell, he became unconscious; when he came to, the present was almost intolerable in its richness and sharpness, as were his most distant and trivial memories.

Lying on his bed, Funes remembers everything, over and over again:

These memories were not simple ones; each visual image was linked to muscular sensations, thermal sensations, etc. He could reconstruct all his dreams, all his half-dreams. Two or three times he had reconstructed a whole day; he never hesitated, but each reconstruction had required a whole day. He told me: ‘ I alone have more memories than all mankind has probably had since the world has been the world.’

Borges often delivered variants on this theme: novels that don’t end; maps that become so detailed they become as large as they territory they describe. But Funes also captures something that is also essential to the human predicament: that we are only ever partly-conscious of the world we inhabit, and our memories must inevitably boil down human experience to a few remembered details; scratches on the surface of time; flowers by the roadside; photographs that preserve special moments the way we want to remember them; books; statues; memorials; gravestones.

All of this goes on in every society, and it also goes on in the Atacama desert. And perhaps because so many complex and surprising human histories have been played out in an environment that is still largely empty, barren, and seemingly indifferent to humanity, humans have often gone to surprising lengths to leave behind some reminders of their presence here.

These messages might consist of prehispanic Indigenous geoglyphs carved on mountainsides like the ‘giant of Tarapacá’, where even non-Indigenous Chileans come from as far away as Iquique to mark the summer solstice and seek blessings and good luck:

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Almost every road in the Atacama is dotted with the shrines or animitas, with which Chileans, even more than most Latin Americans, honour and remember their dead. These shrines are often extremely elaborate. They can be large cabin-like structures built from brick or wood, with the names of the departed, paintings or photographs, and decorated with dried flowers, the Chilean flag and other mementoes. Others are little miniatures; the poorest and most humble might consist of a few stones and pieces of wood. Sometimes, these dried flowers are the only splash of bright colour amongst the beige and grey.

Animitas often commemorate an accident or premature death. Some are illustrated with montages of motorbikes or cars. Others consist of modern geoglyphs showing human figures made with stones, with the names also written in stones. One structure I passed yesterday, simply read ‘Yeye le recordamos (Yeye we remember you’ laid out in white stones on a hillside. There were no white stones on the hillside, so whoever brought them there must have gone to some considerable effort to create this monument.

Why do people do this? Why proclaim the name of someone who will always be a stranger to those who see it, few of whom will ever stop to find out anything more? Perhaps for the reason that Helen de Cruz wrote her books, and for the same reason that the Chinchorro adorned their mummies, because this is one more way of remembering the departed, and ensuring that other people remember them too.

Animitas have a long history. Some of them have been left by miners and nitrate workers from the last century, and have no names at all. But someone felt the need to leave a monument in the desert to commemorate a person they had known and cared about. Perhaps they saw the desert as a blank canvas on which messages like this could be written. Perhaps they knew or sensed that such monuments are likely to last a lot longer in the desert than they are anywhere else, and insisted on proclaiming even the faintest physical memory of the person they had known, regardless of whether the world cared or not.

Whatever the reason, these shrines take their place amongst the cemeteries of nitrate owners and nitrate workers; of Indigenous peoples, miners, soldiers and Chinese slaves who once worked on guano production in the nineteenth century. And there is also another kind of remembrance that has also become part of the iconography of the Atacama in recent years: the commemoration of political prisoners and political dissidents whose remains were hidden and buried in the desert and were never meant to be discovered.

That will be the subject of other posts. But in reminding us of this human desire to remember and be remembered, the shrines of the Atacama, like the Chinchorro mummies, should not depress us. To be depressed by death is as pointless as being depressed by life. To think of death as morbid, is to think of life as morbid.

And as I drive though these lonely desert roads, I will continue to see these shrines as poignant affirmations of the same desire that Helen de Cruz expressed, and also as reminders that even in the world’s driest desert, there have been humans here, who have left these little marks of love and tenderness for passing travellers to take note of, for a few fleeting seconds.

June 24, 2025

Letters from the Desert

Some readers may be old enough to remember Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982). For those who don’t, it’s a mainstream horror film, in which a Californian real estate company builds a planned community on a former cemetery, and an array of vengeful supernatural forces wreak havoc on the hapless suburbanites. Even viewers who didn’t believe in ghosts and spirits did not need much persuasion to suspend disbelief and accept its familiar premise: that if you build houses on cemeteries, it may bring unexpected consequences. Because in most modern Western societies, we don’t want the dead living too close to us, and we certainly don’t want them living underneath us.

The inhabitants of Arica have also discovered that their city was built on a cemetery, though so far the consequences have been less calamitous. Over the years, its inhabitants have become accustomed to finding bodies and body parts in unexpected places. Sometimes human remains are uncovered by wind, sea and earthquakes, or revealed during construction works. In 1983, archaeologists from the University of Tarapacá were called out to visit a trench, where workers laying pipes had found dozens of mummified corpses. In 2004, a hotel expansion at the foot of the Morro cliff face uncovered another series of bodies, and summoned the university’s specialists.

There was a time when Ariceńos didn’t always do this. Sometimes remains simply threw them away or reburied, because locals were fearful of being fined or not being able to finish the work they were doing. One taxi-driver told us how he and his cousins once encountered some mummies on a hillside while out horseriding, and galloped away in fear. It was not uncommon, in some neighbourhoods near the Morro, for children to use body parts as toys, or play football with the occasional skull.

As the world now knows, most of these remains belonged to the Chinchorro people. And in the last fifty years, scientists have come to appreciate the importance of these graveyards, and the people of Arica have also come to embrace the Chinchorro, both as scientific artefacts and as markers of civic and regional identity.

This transformation is the result of a sustained effort by archaeologists and anthropologists at the University of Tarapaca. In 2023, the former Chinchorro settlements in the Arica and Parinacota region were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site - the culmination of a 20-year campaign led by Bernardo Arriaza, the anthropologist Vivien Standen and their team at the university. In citing the Chinchorro as objects of ‘outstanding universal value’, UNESCO paid tribute to the people who ‘successfully adapted to the extreme environmental conditions of a hyper-arid coastal desert’ and whose ‘archaeological sites…are recognized for having the oldest known artificially mummified human bodies.’

Having brought this heritage to the attention of the wider world, Arriaza and his team were obliged to ensure that these sites were protected, and they recognised that this objective could not be achieved without the active participation of the wider public. As a result, they were obliged to look beyond the laboratory, and engage the population in a wider conversation about the Chinchorro sites and their scientific importance. This was not difficult for Arriaza, who is as likely to be found enthusiastically designing an education poster for children, or checking Chinchorro mummy replicas, as he is poring over mummified remains in the laboratory.

But the heritage designation required a wider team with different skills, spanning law, public education, tourism, and private enterprise, in order to protect the sites. One of the consequences of the UNESCO process was the Corporación Chinchorro Marka, a public-private body which carries out educational work on the Chinchorro heritage, and engages in outreach to schools, associations for the elderly and neighbourhood associations.

The Corpoation’s aim, according to the archaeologist Cesar Bories, is ‘to bring everybody to a certain base level of knowledge about Chinchorro culture so that they can work with a good, solid basis of information’ aimed at transforming ordinary members of the public into curators of the Chinchorro. At the Corporation’s offices in downtown Arica, Bories discussed the tensions between heritage preservation and the tourists that heritage status bring to the city. ‘It’s a big challenge to make this look interesting in terms of tourism,’ he said, ‘ because we don’t have Machu Pichu or the Pyramids, with their very distinctive architectural features. What we have are the Chinchorro mummies that are mostly in museums.’

In Arica, what Bories calls, ‘Jurassic Park’-style tourism cannot be achieved without damaging or destroying the Chinchorro sites, and his team have set out to inculcate a sense of public curatorship through workshops, field trips, and visits to schools, with an emphasis on Chinchorro culture as a ‘living culture’ made up of ‘living people not just a mummified culture because sometimes people think they were only dying and making mummies.’

In addition to carrying out interactive activities in which children are given little shovels to dig up replicas of human remains in sand boxes to show how archaeological sites work, the Corporation also works with entrepreneurs, Providing information to make accurate replicas in order to promote ‘a more respectful approach to Chinchorro culture.

Bories believes that Chinchorro have become ‘ a thing related to pride and identity here, because we are a coastal community. If you go to the beach everyday, from 7 am onwards you see fishermen, surfers and guys collecting on the shore, so it’s embedded in the lifestyle of the community here to have this close relationship with the coast and the Chinchorro were the first specialised hunter gatherers here.’

Art has been central to these outreach efforts. The University of Tarapacá has sought out local artists to make mummy replicas and paint and draw the Chinchorro, and there has been no shortage of applicants. I spoke to the sculptor Paola Pimentel and her graphic designer Johnny Vásquéz at their beautiful home near the Morro. The two of them had vivid childhood memories of their first encounter with the Chinchorro, when they regularly encountered human remains while playing with her friends on the slopes of the Morro, or in the tunnels laid for pipes during the construction of their neighbourhood.

Both of them, as Pimentel puts it, were ‘in contact with the Chinchorro culture without knowing anything about the culture or the scope of heritage,’ but the invitation from the university to make replicas opened up a new connection between art and science, and an artistic meeting across the centuries that Pimentel compares to falling in love.

Vásquéz recalled how moved he was by mummies that signified ‘the end of a people, who had the experience of living in a pristine place that was also in the middle of a desert.’ Pimentel described her admiration for the artistic sensibility of the Chinchorro mummies, in which ‘Each one is different, each one is different from another. There’s no single pattern that just gets repeated. Each body shows distinct forms of intervention. You can see in these bodies the subjectivity of whoever carried out the intervention.‘

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Like Bories, Pimental and Vásquez believe that the population of Arica have begun to take pride in the city’s connection to the Chinchorro. I saw plenty of evidence of this myself. The Chinchorro are everywhere in Arica. You see their masks on wall murals, restaurant signs and on buses, and in almost every tourist brochure on the region. Taxi drivers will proudly boast that the Chinchorro were mummifying the dead before the Egyptians, as if they had a hand in it. At the foot of the Morro, the Colon 10 archaeological site where a would-be hotelier uncovered dozens of bodies in 2004, has been turned into a museum. Here, mummies that were too delicate to be removed lie two or three rows deep beneath a glass screen right in the middle of a residential neighbourhood.

One day I visited the Caleta de Camarones (the bay of Camarones) at the foot of the Camarones river, one of the key sites in the UNESCO designation. We drove out through the desert, along the Pan-American highway, past the ever-present animitas (shines) with which Chileans honour the prematurely-departed. After nearly two hours we turned off a little road down to the bay, where we paused to admire Paola Pimentel’s imposing statues.

At the dried-up river mouth, we parked outside a little settlement made up of plank and plywood shacks. We hadn’t been there long when Jorge, the Corporation Chinchorro’s local guide came bounding out to meet us, and offered to show us the local Chinchorro sites. Jorge had been living in this isolated bay for thirty years, after he was run over and seriously injured at the age of thirteen. When doctors told his parents he needed to live in a more peaceful place, his parents brought him here.

In addition to running a local restaurant with his wife, he acts as a guide, curator and guardian of the Chinchorro heritage, and he takes these duties seriously. He has attended Bernardo Arriaza’s lectures, and he knows the area like the back of his hand. He showed us the place where some of the first mummies had been found, and took us onto the cliffs overlooking the sea, where the Chinchorro had once cooked, and climbed down to the rocks to collect mussels and shellfish. To my disbelief, Jorge showed us arrowheads, stratified shell middens and original Chinchorro stone pestles, lying around like the remnants of a recent picnic.

These were artefacts that would normally be in a museum, yet none of them had been stolen, and Jorge was on hand to see that no one tried to steal them. All these relics, he told us proudly, were part of the Chinchorro heritage, and if people wanted to see them, he was there to show them where they could be found. At one point, he covered an arrowhead with dirt, just in case, while making sure that he knew where to find it.

I was almost as impressed by him as I was by the place, as he casually told us that a piece of clothing was probably Tiwanaku, and pointed out the remains of an Inca settlement on the other side of the river.

But what impressed me most, were the people who had once lived in this remote wild place, and made it their home for thousands of years. I imagined them, running down the slopes, tripping and injuring themselves and acquiring the injuries that have been found on so many adult bodies. I imagined them sitting round the remains where we stood, talking, laughing, chanting and maybe singing.

The poet Octavio Paz once wrote: ‘For the first time in history, we are contemporaries of all mankind.’ It’s an attractive proposition, but it’s not strictly accurate. As far as the past is concerned, we can never be contemporaries. We can never fully understand what it was like to live in a place like the Caleta de Camerones 7,000 years ago. All we can do is pore over their remains, and use science, art and the imagination to piece together some fragments of their lives and beliefs.

This is not an academic exercise. It is worth the effort. Because even though we can never the ‘contemporaries’ of the Chinchorro, we can be sympathetic observers. We can recognise that they, like us, did not want to die or say goodbye to the people they loved. We can understand that they, like us, were mystified by why these things happened, and that they, like us, wanted the future to remember them.

And now thousands of years later, in ways that they could not possibly have imagined, the former inhabitants of this wild lonely bay are remembered. The people who lived with their ancestors close at hand have become the ancestors of the people of Arica, and the city of the dead has become part of the city of the living.

June 22, 2025

Letters from the Desert

In most deserts, the dead don’t last long. Most of us will know this, even if we have never been anywhere near a desert. Maybe we’ve read newspaper reports of the migrants who die of dehydration or exposure in the deserts of northern Mexico or southern frontiers - their bodies reduced to desiccated, leathery husks with only a cursory resemblance to a human. Or perhaps we’ve seen images of animals on the fringes of the Sahara, reduced by sand, wind, sun and predators to the bare white bone that often appear in news articles about desertification drought and climate change.

In the Atacama an entirely different process occurs. Here, extreme aridity and a nitrate-rich soil have combined to impede the bacterial growth that would normally finish off any organic matter buried or left out in the open. These conditions have turned the desert into a natural mortuary, where the dead can be preserved in a mummified but still-recognisable physical form for hundreds and even thousands of years.

The history of the Atacama is replete with such remains, from the mummified bodies of dead miners, and the victims of serial killers, to political prisoners murdered and dumped in the desert during the Pinochet dictatorship. But the oldest bodies in the Atacama belong to one of the most intriguing, mysterious and enigmatic of all South America’s Indigenous peoples – the marine hunter-gatherers known as the Chinchorro people. ‘Chinchorro’ is a modern term that history has bestowed on the peoples who first settled the Pacific coasts from Peru into northern Chile about 7,000 years ago.

Although the peoples who formed what anthropologists call the ‘Chinchorro complex’ have long since vanished from history, they have acquired a remarkable historical afterlife as a result of the cultural practice for which the Chinchorro are most famous – their highly-skilled and meticulously-executed techniques of artificial mummification.

About 5,000 years ago – some 2,000 years before the Egyptians, the Chinchorro began to mummify and decorate the bodies of their dead. They continued to do this for more than 3,000 years, developing an intricate methodology and belief system that continues to dazzle and intrigue anthropologists.

This scientific fascination wasn’t always present. When the German archaeologist Max Uhle first began excavating mummies from Chinchorro beach in 1917 – their significance was not fully-appreciated. This was a period in which archaeologists and anthropologists still tended to associate cultural and religious sophistication with urbanisation and priestly hierarchies, rather than ‘primitive’ or ‘savage’ societies where such sophistication was supposedly absent.

Having spent much of the last two years delving into the works of Victorian anthropologists who expounded such theories, I had already become wearyingly familiar with these tedious speculative trajectories before I came across the Chinchorro. Here we go again, I often found myself thinking, as I trudged through yet another Victorian gentleman’s account of the ‘descent of man’ through various stages of savagery and civilisation. ‘Savages’ - a word applied to virtually any Indigenous people, invariably occupied the lowest rung of humanity, with little to distinguish them from animals.

Such peoples, the consensus held, were a retarded form of humanity. Their lives were short, nasty and brutish. Devoid of culture, incapable of domesticity, love and affection, prone to cannibalism - they were doomed to ‘extinction’ by the march of (white) civilisation - an outcome that was tragic but also inevitable.

None of these scholars knew of the Chinchorro, because no one did. And it would have been interesting to see how they would have have reacted if they had known, because these hunter-gatherers could not be further removed from the reductionist stereotypes that still continue, in various insidious ways, to underpin western attitudes towards Indigenous peoples.

The Chinchorro were not urbanised, which might have at least put them in the ‘barbarian’ category that 19th century scholars conferred on the Incas and the Mayans. Living in small isolated groups on the beaches of the Pacific, they built no permanent settlements, and wore no clothes except for reed skirts and loin clothes. Their technology was primitive, but adequate for their material needs. For thousands of years, they lived from fish, shellfish and hunting sea lions and other animals. And yet they developed ingenious and artistic techniques of artificial mummification, using only the materials that were available to them.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The Chinchorro understood enough about the human anatomy to know what decayed and what survived. They removed the brain and internal organs, before peeling the skin to replace removed organs with reed and mud. They then created clay masks to cover the face and skull, which they painted using red, black and white clay or manganese. They used sticks to strengthen the arms and spine, reed ropes to hold these structures together or bind the skull to the spine, and topped these creations with human or animal hair.

Since Uhle’s discoveries in 1917, some 300 of these mummies have been found in various places in the Atacama, particularly in and around the city of Arica, most of which have been discovered in the last fifty years. On our first day in the city, we drove out to see some of them at the University of Tarapacá’s archaeological museum in the former oasis of the Azapa Valley. The mummies are housed in a grey block-like building, amongst tall, swaying palms and banana trees, alongside the foundation stones of an old Spanish hacienda.

I had seen photographs of these mummies before, but it was deeply moving to see some fifteen bodies behind a glass screen in a specially-heated room with dimmed lights. Lying on their individual benches, they seemed hover in the semi-darkness - inhabitants of some intermediate zone between the living and the dead.

Some had masks on their faces, with the slits for eyes and mouth that were part of Chinchorro mummification practices, and which enhanced their humanity. Some had decayed to the point when they had no feet or hands; others had all their fingers remarkably intact:

What struck me about these mummies was the tenderness, as well as the artistry that went into their creation, and also their egalitarianism. Because unlike the Egyptians, there were no hierarchies involved. They Chinchorro didn’t just mummify kings, queens and aristocrats - they mummified everyone. Children were a persistent object of mummification. The youngest children – even foetuses - had been mummified.

One display case contained an embryo attached to a stick , with a flattened space on which an eyes and a mouth had been drawn in order to create the semblance of personhood:

The mummification of children, some scientists believe, reflected the high incidence of infant mortality amongst the Chinchorro people, that may have been a result of the high incidence of natural arsenic in Atacama rivers. Whatever the cause, it was clear that the Chinchorro valued their children enough to preserve them into the afterlife. And with the help of the desert, they succeeded.

After so many thousands of years, these mummies have inevitably experienced some decay. These striking creations by the local artist Paola Pimentel give an idea of who they might have looked at the time. Here:

And here:

Whether real or imagined, these bodies suggest an attitude to death that is very different from the Christian tradition. In medieval and early modern Europe, death was often depicted as a grim warning. Tapestries, paintings and mementos mori emphasised the decay of the body as a reminder of the ephemeral nature of human life - the better to encourage a virtuous and devout life and concentrate attention on the fate of the soul in the hereafter.

The Chinchorro refused to accept this inevitability. Living in a world where death was a constant and inexplicable presence, they set out to beautify and preserve even the smallest and most insignificant members of their community who were being taken from them. They buried their dead alongside their camps, with slits in their masks to create an avenue of communication between the dead and the living.

The museum isn’t just concerned with the dead. It also shows the tools the Chinchorro used to fish and hunt with, from harpoons and arrows to knives and hooks made from shells. It discusses the propensity to extososis (benign bone tumours) in the ears of adult Chinchorro males, probably as a result of diving; the damaged teeth amongst female corpses due to stripping flesh and chewing sinew to make it soft.