Mitali Perkins's Blog, page 22

September 26, 2012

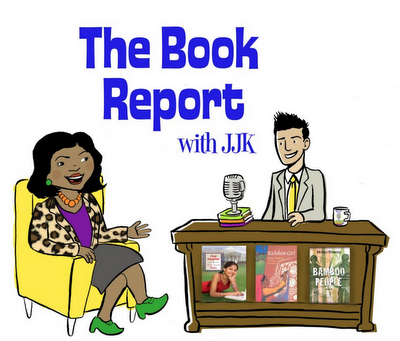

On The Radio With Jarrett J. Krosoczka!

I'm on

The Book Report with JJK

at SIRIUS XM'S KiDS Place LiVE this Thursday 9/27 at 5:40 p.m. ET / 2:40 p.m. PT. And in real life as in the cartoon he drew below, my head IS twice as wide as Jarrett's! Now I have to get a pair of green pumps and an orange necklace.

Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Published on September 26, 2012 07:46

September 24, 2012

Book Launch Parties for Reluctant Authors

Several writer buddies have asked lately if I think in-real-life launch parties are worth it in a virtual age. If you're about to celebrate the publication of your first (or second or third) book, should you throw a book launch party for friends, fans, and family members?

I'm a huge social media fan, but there's still no better way to invite people into your stories than to appear in person. You spread the word about the book through press coverage and social media, creating a ripple effect around each event. You support and encourage the indie booksellers who faithfully support and encourage our books.

How many events should you plan?

Admittedly, launch parties are a lot of work. Thankfully, publishers and booksellers share the work load, but the ball is in the author's court. I'm fundamentally an introvert, like many writers, and the experience of being in the limelight is draining. That's why I usually aim for only one party per book, but try to schedule a West Coast launch and an East Coast launch—places where I know people.

Do you plan the party for young readers or for the adults who usually show up?

I cherish the teen and tween young readers who set aside time to come to these events. I know how busy they are. But I also see each launch as a chance to nurture a community of adults who care about those young readers. More and more adults are reading YA books. They want good storytelling imbued with hope, and they're turning to our genre to find it. At my parties, I welcome both the young and the young at soul.

One key is to tell a couple of interesting stories behind the story so attendees feel privy to an inside scoop and invest in some book-appropriate, inexpensive giveaways. For Bamboo People, for example, I gave away bamboo bookmarks I'd picked up in a Thai market. For Monsoon Summer, I bought a bunch of incense sticks from our local Indian grocery and handed those out. Brainstorm ideas for your book with a buddy or two.

How can social media help pull everything together?

These tools are superb ways to gather a story-hungry circle around the fire. On Facebook, I take the time to sort my friends into geographical lists and target my invites that way, trying to make them as individualized as possible. On Twitter, I find folks in the area outside my writing circles who might be interested in the subject matter of the book and invite them to attend via a personalized tweet.

Even if not many people show up, don't be discouraged. Ask someone to take photos so that you can multiply the event by posting them on twitter, facebook, pinterest, and your blog if you have one. In fact, that's the key to seeing the event's publicity potential—understanding the multiplication effect of getting the word out about your book, first by invitations and announcements, then via the press and your delightful bookstore host, and lastly through social media's tags and share functions.

The bottom line, though, is that a launch party is a celebration of your book. By planning and hosting the event, you underline your pride and joy in this story as you send it out to readers. Bon Voyage, new book!

Authors Laya Steinberg (THESAURUS REX) and Karen Day (A MILLION MILES FROM BOSTON) celebrate the publication of Karen's NO CREAM PUFFS at Wellesley Booksmith.

Other questions? Ask them below, or share your favorite tips for successful book launch parties.

Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

I'm a huge social media fan, but there's still no better way to invite people into your stories than to appear in person. You spread the word about the book through press coverage and social media, creating a ripple effect around each event. You support and encourage the indie booksellers who faithfully support and encourage our books.

How many events should you plan?

Admittedly, launch parties are a lot of work. Thankfully, publishers and booksellers share the work load, but the ball is in the author's court. I'm fundamentally an introvert, like many writers, and the experience of being in the limelight is draining. That's why I usually aim for only one party per book, but try to schedule a West Coast launch and an East Coast launch—places where I know people.

Do you plan the party for young readers or for the adults who usually show up?

I cherish the teen and tween young readers who set aside time to come to these events. I know how busy they are. But I also see each launch as a chance to nurture a community of adults who care about those young readers. More and more adults are reading YA books. They want good storytelling imbued with hope, and they're turning to our genre to find it. At my parties, I welcome both the young and the young at soul.

One key is to tell a couple of interesting stories behind the story so attendees feel privy to an inside scoop and invest in some book-appropriate, inexpensive giveaways. For Bamboo People, for example, I gave away bamboo bookmarks I'd picked up in a Thai market. For Monsoon Summer, I bought a bunch of incense sticks from our local Indian grocery and handed those out. Brainstorm ideas for your book with a buddy or two.

How can social media help pull everything together?

These tools are superb ways to gather a story-hungry circle around the fire. On Facebook, I take the time to sort my friends into geographical lists and target my invites that way, trying to make them as individualized as possible. On Twitter, I find folks in the area outside my writing circles who might be interested in the subject matter of the book and invite them to attend via a personalized tweet.

Even if not many people show up, don't be discouraged. Ask someone to take photos so that you can multiply the event by posting them on twitter, facebook, pinterest, and your blog if you have one. In fact, that's the key to seeing the event's publicity potential—understanding the multiplication effect of getting the word out about your book, first by invitations and announcements, then via the press and your delightful bookstore host, and lastly through social media's tags and share functions.

The bottom line, though, is that a launch party is a celebration of your book. By planning and hosting the event, you underline your pride and joy in this story as you send it out to readers. Bon Voyage, new book!

Authors Laya Steinberg (THESAURUS REX) and Karen Day (A MILLION MILES FROM BOSTON) celebrate the publication of Karen's NO CREAM PUFFS at Wellesley Booksmith.

Other questions? Ask them below, or share your favorite tips for successful book launch parties.

Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Published on September 24, 2012 13:13

September 17, 2012

Boston Public Library's Literary Lights for Children 2012

Sunday, September 30, 2012, 2:00 pm – 5:00 pm

Bates Reading Room, Central Library, Copley Square

The Associates of the Boston Public Library is pleased to invite you

to the fourteenth annual Literary Lights for Children tea party on

Sunday, September 30th in the beautiful Bates Reading Room of the Boston

Public Library. The 2012 honorees are:

Kevin Hawkes

Christopher Paolini

Mitali Perkins

Gary Schmidt

Books illustrated by

Kevin Hawkes

Books by

Christopher Paolini

Books by

Mitali Perkins

Books by

Gary Schmidt

"Literary Lights for Children" seeks to raise awareness of

children's literature, promote literacy, honor children's authors, and

raise money for the Boston Public Library's children's services and

collections. Students selected from Boston area schools introduce and

present the awards to each of the honored authors. The honorees then

discuss their writing careers and share their love of books with the

audience of over 400 children and adults. Tea refreshments are served.

to the Literary Lights Tea Party

Immediately following the tea party, there will be a book

signing session. Books will be available for sale, or children are

welcome to bring their own books. The book sales & signing portion of the program is free and open to the public.

See past Literary Lights for Children honorees

For more information and sponsorship opportunities, please contact the Associates Office at:

Associates of the Boston Public Library

700 Boylston Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02116

Phone: 617-536-3886

Fax: 617-536-3813

Email: associates@bpl.orgCome visit me on the Fire Escape!

Published on September 17, 2012 08:47

September 14, 2012

Reading is Fundamental's new Multicultural Book Collection focuses on Science, Math, and Technology

Reading is Fundamental's new Multicultural Book Collection focuses on Science, Math, and Technology

Reading is Fundamental's new Multicultural Book Collection focuses on Science, Math, and Technology

RIF Releases STEAM Multicultural Book Collection Connecting STEM, the Arts and Early Learning WASHINGTON, Sept. 12, 2012 /PRNewswire-USNewswire/ -- Reading Is Fundamental (RIF) is launching a multi-year early childhood literacy campaign to inspire the next-generation of innovators through an approach…

Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Published on September 14, 2012 09:03

September 12, 2012

2012 Teens Between Cultures Prose Contest Winner

I'm delighted to announce the winner of the 10th annual Mitali's Fire Escape Teens Between Cultures Prose Contest. In the past, I've award three prizes (first, second, third), but this year I decided to pick only one. Agonizingly, I narrowed the best entries to three and then asked my friend, author and teacher Cynthia Leitich Smith, to select the winner. Here it is—enjoy.

Chow Mein with a Chance of Meatballs

by Whitney S., Age 18

Growing up as the headstrong daughter of Chinese immigrants, I – surprisingly – didn’t question my parents’ strict emphasis on academic achievement. I didn’t fight back against the forced piano lessons, I didn’t begrudge the embargo on sleepovers, and I didn’t sulk (for long, anyway) when I brought home an A-studded report card and got only distracted nods in response. No, I accepted everything except the food.

I first realized my own gastronomical ignorance in elementary school, when my friends discussed their favorite restaurants and I could only name the two fast-food places I passed daily on my way to school. Before that, I had lived complacently under what I assumed were the unspoken, unquestioned rules of my household: No sodas, candies, or carb-based munchies could be found in the pantry. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner were served at prescribed times, with one afternoon snack of fruit and no nibbling allowed in between. Getting a hamburger from McDonalds was a twice-a-year treat for outstanding behavior (like winning a spelling bee) or consolation for a serious misfortune (like getting stitches when I cut my scalp open). And formal restaurants? I was lucky I knew what real, “Western” silverware looked like.

“Why don’t we ever eat out?” I demanded once, in a fit of indignation.

“Do you want to weigh 500 pounds? Americans put so much oil and flavorings in their cooking, it’s disgusting,” said my mother in dismissive Chinese. “And how much money we’d waste if we ate out every week, like American families do! Do you think we’re rich?”

My parents loosened up sometimes – if only to sample genuine Chinese restaurants where the owners and servers all spoke Chinese. They’d order standard mainland dishes, furrow their brows as they ate, and spend the rest of the night debating the authenticity of the food. For someone like me, with a sweet tooth and an adventurous appetite, it simply wasn’t enough.

I could pinpoint with 99% accuracy what we’d be having for dinner any given night, before even coming home from school. There was always the essential staple, rice. Then there was steamed or stir-fried bok choy (and if not bok choy, some other leafy green vegetable). Lastly, a meat dish, maybe mixed with more vegetables and maybe standing alone. On the rare occasions that we didn’t eat rice, we ate dumplings or noodles. And oh, how I hated fulfilling popular stereotypes – but we did all of the above with chopsticks.

My classmates complained about eating Brussels sprouts; they whined about not being able to have dessert before the entrée. My dreams (okay, perhaps my speculations when I got bored) were made of the stews, casseroles, lasagnas, pizzas, and steaks they ate at home. My peers gasped at the multisyllabic words I recited and rolled their eyes whenever I churned out another math problem at record speeds. How would they see me, though, if they knew that the great Whitney had no idea how to pay the check at a restaurant?

When my parents finally allowed me to carry pocket money around, I got sneaky. My middle school hosted a snack booth, and I felt a small high every time I purchased a forbidden pastry or soda. But it was immediately followed by an overwhelming cascade of guilt. I saw, in my mind’s eye, my mother lecturing me on how hard she worked to cook meals with minimal salt and oil, how much she despised “American” foods, which were inarguably fatty and unnatural. A part of me always hung her head in shame, promising never to venture down the road to sin again. The other part of me wanted to lash out against my parents. Was it really such a big deal if I deviated from their oh-so-precious customs here and there? I was a model child in every other department. Fortunately, I had never been bullied for my ethnicity; in my stubborn independence, I had rarely folded under the pressure to conform either. But this, the food – it was my way of saying Yes, I do want to be an American! I do want to share in a part, however trivial, of this society!

My parents started to relax their grip when I entered high school, most likely because they grew worried. “Stop studying so much, Whitney,” they told me. “You’re too stressed. Go out with your friends once in a while.” That, and once the trips I took with clubs dragged on past lunchtime, it became inevitable that my teammates and I would stumble into a restaurant. Learning basic skills like ordering from the menu and tipping etiquette were cheek-reddening experiences, mortifying both for me and my friends. I would explain awkwardly that my parents were traditional, that they – cue self-deprecating chuckle here – disapproved of American cooking, for some convoluted reason. I was lucky; most friends nodded and smiled and didn’t ask anything more. Their seeming acceptance soothed my insecurities, but not by much.

It was difficult for me, when I was younger, to justify my parents’ prejudices. How could they be so closed-minded? I thought angrily. Did they want our family to be outcasts? In my childish bravado, I would often proffer various favorites (“They’ll change their minds when they taste this spaghetti!”). As time passed and my parents kept turning away my offerings, though, I had to swallow the truth. They weren’t going to change. They were middle-aged immigrants; they had grown comfortable with their ways, which had endured the grueling transition to a different hemisphere.

But that doesn’t mean I have to remain a shut-in. My parents have begun to loosen their hold in this tug-of-war. I still keep a rigid diet at home, but I have been allowed to sample multicultural cuisines, even if it is always by myself and always out of necessity. My parents don’t understand it, but they are finally acknowledging it. For me, cultural immersion and exploration will always lie in the next order of macaroni and cheese.

Whitney on growing up between cultures:

The hardest thing about balancing two cultures is trying to fit in with other kids when you're young. Most kids now have been brought up to be tolerant and accepting of other cultures, but there are still those who are narrow-minded or just not ready to accept others who are different. I definitely felt a distance between me and other kids when I was young because of the different traditions I practiced at home.

The best thing about balancing two cultures is enjoying the added richness to your life when you're older. I can speak two languages, make authentic foods from different cuisines, enjoy two different styles of entertainment, and connect to people from two different ethnic backgrounds. Now that I can appreciate the depth that being both Chinese and American has brought me, multiculturalism has become a benefit rather than a burden.

Photo courtesy of Gary Soup via Creative Commons.Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Chow Mein with a Chance of Meatballs

by Whitney S., Age 18

Growing up as the headstrong daughter of Chinese immigrants, I – surprisingly – didn’t question my parents’ strict emphasis on academic achievement. I didn’t fight back against the forced piano lessons, I didn’t begrudge the embargo on sleepovers, and I didn’t sulk (for long, anyway) when I brought home an A-studded report card and got only distracted nods in response. No, I accepted everything except the food.

I first realized my own gastronomical ignorance in elementary school, when my friends discussed their favorite restaurants and I could only name the two fast-food places I passed daily on my way to school. Before that, I had lived complacently under what I assumed were the unspoken, unquestioned rules of my household: No sodas, candies, or carb-based munchies could be found in the pantry. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner were served at prescribed times, with one afternoon snack of fruit and no nibbling allowed in between. Getting a hamburger from McDonalds was a twice-a-year treat for outstanding behavior (like winning a spelling bee) or consolation for a serious misfortune (like getting stitches when I cut my scalp open). And formal restaurants? I was lucky I knew what real, “Western” silverware looked like.

“Why don’t we ever eat out?” I demanded once, in a fit of indignation.

“Do you want to weigh 500 pounds? Americans put so much oil and flavorings in their cooking, it’s disgusting,” said my mother in dismissive Chinese. “And how much money we’d waste if we ate out every week, like American families do! Do you think we’re rich?”

My parents loosened up sometimes – if only to sample genuine Chinese restaurants where the owners and servers all spoke Chinese. They’d order standard mainland dishes, furrow their brows as they ate, and spend the rest of the night debating the authenticity of the food. For someone like me, with a sweet tooth and an adventurous appetite, it simply wasn’t enough.

I could pinpoint with 99% accuracy what we’d be having for dinner any given night, before even coming home from school. There was always the essential staple, rice. Then there was steamed or stir-fried bok choy (and if not bok choy, some other leafy green vegetable). Lastly, a meat dish, maybe mixed with more vegetables and maybe standing alone. On the rare occasions that we didn’t eat rice, we ate dumplings or noodles. And oh, how I hated fulfilling popular stereotypes – but we did all of the above with chopsticks.

My classmates complained about eating Brussels sprouts; they whined about not being able to have dessert before the entrée. My dreams (okay, perhaps my speculations when I got bored) were made of the stews, casseroles, lasagnas, pizzas, and steaks they ate at home. My peers gasped at the multisyllabic words I recited and rolled their eyes whenever I churned out another math problem at record speeds. How would they see me, though, if they knew that the great Whitney had no idea how to pay the check at a restaurant?

When my parents finally allowed me to carry pocket money around, I got sneaky. My middle school hosted a snack booth, and I felt a small high every time I purchased a forbidden pastry or soda. But it was immediately followed by an overwhelming cascade of guilt. I saw, in my mind’s eye, my mother lecturing me on how hard she worked to cook meals with minimal salt and oil, how much she despised “American” foods, which were inarguably fatty and unnatural. A part of me always hung her head in shame, promising never to venture down the road to sin again. The other part of me wanted to lash out against my parents. Was it really such a big deal if I deviated from their oh-so-precious customs here and there? I was a model child in every other department. Fortunately, I had never been bullied for my ethnicity; in my stubborn independence, I had rarely folded under the pressure to conform either. But this, the food – it was my way of saying Yes, I do want to be an American! I do want to share in a part, however trivial, of this society!

My parents started to relax their grip when I entered high school, most likely because they grew worried. “Stop studying so much, Whitney,” they told me. “You’re too stressed. Go out with your friends once in a while.” That, and once the trips I took with clubs dragged on past lunchtime, it became inevitable that my teammates and I would stumble into a restaurant. Learning basic skills like ordering from the menu and tipping etiquette were cheek-reddening experiences, mortifying both for me and my friends. I would explain awkwardly that my parents were traditional, that they – cue self-deprecating chuckle here – disapproved of American cooking, for some convoluted reason. I was lucky; most friends nodded and smiled and didn’t ask anything more. Their seeming acceptance soothed my insecurities, but not by much.

It was difficult for me, when I was younger, to justify my parents’ prejudices. How could they be so closed-minded? I thought angrily. Did they want our family to be outcasts? In my childish bravado, I would often proffer various favorites (“They’ll change their minds when they taste this spaghetti!”). As time passed and my parents kept turning away my offerings, though, I had to swallow the truth. They weren’t going to change. They were middle-aged immigrants; they had grown comfortable with their ways, which had endured the grueling transition to a different hemisphere.

But that doesn’t mean I have to remain a shut-in. My parents have begun to loosen their hold in this tug-of-war. I still keep a rigid diet at home, but I have been allowed to sample multicultural cuisines, even if it is always by myself and always out of necessity. My parents don’t understand it, but they are finally acknowledging it. For me, cultural immersion and exploration will always lie in the next order of macaroni and cheese.

Whitney on growing up between cultures:

The hardest thing about balancing two cultures is trying to fit in with other kids when you're young. Most kids now have been brought up to be tolerant and accepting of other cultures, but there are still those who are narrow-minded or just not ready to accept others who are different. I definitely felt a distance between me and other kids when I was young because of the different traditions I practiced at home.

The best thing about balancing two cultures is enjoying the added richness to your life when you're older. I can speak two languages, make authentic foods from different cuisines, enjoy two different styles of entertainment, and connect to people from two different ethnic backgrounds. Now that I can appreciate the depth that being both Chinese and American has brought me, multiculturalism has become a benefit rather than a burden.

Photo courtesy of Gary Soup via Creative Commons.Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Published on September 12, 2012 08:00

September 11, 2012

Andrew Karre on Editing in the "YA Boom" Era

Yesterday on Twitter , I shared a link to an article in the Guardian about a "new" trend in publishing — a genre of books labeled for "New Adults," a.k.a. readers aged 14-35. Andrew Karre , editorial director of Carolrhoda books , responded with a one-word tweet: "Preposterous." Intrigued, I invited him out to the Fire Escape to explain.

Could you tell us why you think setting up a "New Adult" label is nuts?

It’s nuts because I think it’s a backwards way to make art. Allow me to elaborate further after I answer your last question.

Why do you think the YA genre has boomed recently?

A number of factors have pushed the boom in the past decade. Bear in mind, this is driven more by anecdotal observation and hunch than anything else. I’d actually love to hear somebody who was closer to the action take on the question.

Demographics. I believe the teenage population of the US crested at an all-time high sometime around 2007. I have no idea where I saw that number, but I know I saw it.

My sense of the lasting legacy of Harry Potter is that the series made books and authors something that existed in real time for teens and pre-teens. In other words, kids knew when these books were coming without any intermediation; they wanted to share their experiences (and they could, globally); and they expected the author to be a public figure, preferably one they could interact with. Publishing doesn’t notice much, but we noticed this. I’ve spoken about this at length in Hunger Mountain.

It became possible to walk into a bookstore and buy a YA novel without walking through a section of picture books. I attribute this to B & N, but I don’t know for sure. I bet Joe Monti does. Libraries have wisely followed the trend, it seems to me. (Our own, recently built Minneapolis Central Library placed the teen center in a nook completely separate for most of the rest of the library and as far from children’s section as possible. It’s a perfect bit of design in my opinion.)

And I’m probably forgetting another factor.

How (if at all) has this boom affected your editorial style?

Insofar as the fact of the YA boom has allowed me to have the job I do, it’s affected my editorial style. If publishers hadn’t wanted to add YA lists over the last decade, I’d be doing something entirely different in all likelihood.

Beyond that, though, my style is more inward facing than it is outward looking. Adolescence as a cultural phenomenon is endlessly interesting to me. I see teenage stories everywhere—ask my wife. I firmly believe we--late modern humans--created the teenage years and that those years are one of a handful of roughly universal and largely public experiences humans have in western culture. And I think this makes it a very good subject for art (in much the same way war, parenthood, falling in love, and dying are great subjects for art). This is why I say I think YA is a genre about adolescence rather than a product category for adolescents. The first thing this frees me from is answering the unanswerable question: “What do teens want?” In fact, that teenagers read the majority of YA is kind of coincidental to my editorial style, to be honest. I love teenagers dearly, but I make books for readers, first and foremost. (I get away with it because most teenagers are as curious about themselves as I am about them.) In my utopia, there is no YA section, and authors don’t self-identify as YA novelists, but there are tons of YA novels. I don’t think this is the only approach to YA, the right approach to YA, or even the best. But it’s mine and I’m fond of it.*

So, what does this have to do with "New Adult"? My (admittedly meager) understanding of what’s meant by “new adult” is that it’s an audience description (I’ve seen 14-35, and that is preposterous)—something akin to a TV demographic. This is a great way to sell advertising (I guess), but I think it’s a s***** way to make art. For me, genres are campfires around which artists gather, not ways of understanding an audience for art or entertainment. I think there easily could be a bonfire to be built around the shifting definition of adulthood. I think that’s a real cultural phenomenon, but it needs to come from the writers not the marketers.

* One big caveat: I think it’s important to push myself into less comfortable places as an editor, so it’s not hard to find inconsistencies with this approach among the ostensibly YA books I’ve edited. No Crystal Stair, for example, doesn’t fit neatly into any of the foregoing. It’s just a great book that was a joy to publish.

Thanks, Andrew! As a writer, I resonated with this statement: "The first thing this frees me from is answering the unanswerable question: 'What do teens want?' ... I love teenagers dearly, but I make books for readers, first and foremost. ” Fellow writers, check out Carolrhoda's submission policy.

Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Published on September 11, 2012 07:24

September 5, 2012

2012 Teens Between Cultures Poetry Contest Winner

I'm delighted to announce the winner of the 10th annual Mitali's Fire Escape Teens Between Cultures Poetry Contest.

In the past

, I've award three prizes (first, second, third), but this year I decided to pick only one. This made judging the contest harder than ever. To compound the difficulty, I received more entries this year than ever before and many of those were stellar. Agonizingly, I narrowed the best to three and then asked my friend, brilliant poet Naomi Shihab Nye, to select the winning poem.

Naomi confirmed my opinion: in her words, Moon Cake by Cathy Guo is "lush and elegantly cadenced and heartbreaking," and deserved the win. With thanks to Naomi for helping me with this tough decision, please enjoy the 2012 Fire Escape Teens Between Cultures Poetry Contest winner.

Photo courtesy of jimmiehomeschool, via Creative Commons. Stay tuned for the prose contest winner!Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Naomi confirmed my opinion: in her words, Moon Cake by Cathy Guo is "lush and elegantly cadenced and heartbreaking," and deserved the win. With thanks to Naomi for helping me with this tough decision, please enjoy the 2012 Fire Escape Teens Between Cultures Poetry Contest winner.

Moon Cake

by Cathy Guo

My mother had beautiful hands. Poised

with a brush and a palette of color,

she showed me the movement of landscape

and its words: da hai, for the sea she never

saw in childhood,

sha mo, for the desert sand of Lanzhou

in her mouth,

cao ping, for the great plains in which hundreds of

Tibetan girls sang with skirts

made from jasmine petals and rain

that was on the verge of hail.

My mother had beautiful hands.

She coiled them around the moon cakes

when our lunar calendar turned, holding mine

gently as she traced the outline of a

sky. Moon cakes are a

cure for loneliness, for homesick. We see

the same moon here and there, we have the

same moon inside us. I was then too young

to understand tradition or void.

My mother had beautiful hands.

Time would not be as merciless,

its hair pushed back with shoulders set hard

in a Western way. My mother

slowly developed an ache

from long hours at the fabric

factory, and the year I turned twelve

she began to wear gloves.

My mother had beautiful hands.

With them she hid the outline of

a crescendo, quiet breakage like a

stone wrapped secretly in silk.

The chasm in mistranslation between

us grew with every Zodiac’s turn.

Moon cake, moon cake.

How the constellation

inside me trembles even now,

remembering.

Photo courtesy of jimmiehomeschool, via Creative Commons. Stay tuned for the prose contest winner!Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Published on September 05, 2012 09:15

August 20, 2012

TU BOOKS: Why Target an Author's Race in an Award?

TU Books , the fantasy, science fiction, and mystery imprint of Lee and Low, recently announced their first annual New Visions Award . "The New Visions Award will be given for a middle grade or young adult fantasy, science fiction, or mystery novel by a writer of color," they say.

I wondered why the award was restricted to the race of the author rather than of the characters, and asked Stacy Whitman, editorial director of TU BOOKS, about her take on this sticky issue. Here's the email exchange between the two of us (shared with Stacy's permission):

Mitali: Hi Stacy. Just wondering why you decided to focus the award on "writers of color" rather than "main characters of color"?

Stacy: This is like the Lee and Low New Voices Award , which is aimed at discovering new voices of color, given that so many writers are white. Everyone is still welcome to submit to our regular submissions. Hope that clears it up.

Mitali: Yes and no. I've always wondered how Lee and Low defined "of color."

Stacy: It's a good question. Here's the answer Louise usually gives writers who ask about it for New Voices, which I'll be adapting as people start to ask me:

While our company does acknowledge and actively work with Caucasian authors and illustrators, our New Voices contest specifically promotes the work of new writers who are not Caucasian. We use the term “color” in the commonly accepted way to refer to those writers and readers who might otherwise be referred to as members of minority populations (African Americans, Asian Americans, Latin Americans, and Native Americans), but who are fast becoming larger and larger percentages of the United States population. We apologize if you find this terminology exclusionary, but it is meant merely to be descriptive. For want of a better term, we use what is in common usage throughout the country.

As a company founded with the mission of creating books in which children of color can see themselves in the stories they read, we feel it is critical to acknowledge these unheard voices. In the mainstream world of children’s publishing—statistically dominated by works by and about Caucasians—writers of color and their stories for children have and continue to slip through the cracks, making up a small percentage of the children’s books published each year. Aside from our small efforts to promote new writers from diverse communities, you will find there are national children’s book awards that have similar focuses, for example the Coretta Scott King Award which acknowledges African American authors and illustrators, and the Pura Belpré Award which acknowledges Latino authors and illustrators.

It can be tricky—I personally prefer the author to define themselves, rather than for myself to define it. And for me it includes multiracial people (Tobias Buckell, an editor of Diverse Energies, for example, is half black and half white, even though many people just looking at him would assume he is "just" white, which is a complicated genetic thing that society oversimplifies). But what it comes down to is that we're trying to help discover new voices from underrepresented groups through this contest.

Me: Thanks, this is helpful. My opinion is that with all the mixing and melding going on, any authentic experience of a writer will ring through in the fiction if we focus on the culture/race of the character rather than of the author. If an upper middle class Bengali woman like me writes about a poor Bengali fisherman's son (as I'm doing right now), I'm crossing huge borders of class, gender, and caste, but not race ... may I write this story? I certainly hope so, because I am! Anyway, the goal is to widen the choices of fiction for readers so that we're not all rooting solely for educated upper class heroes with European roots ... the question is how to get there.

Stacy: Exactly, and this is pretty much a two-pronged approach for us--encouraging everyone to submit to the main submissions, but also doing the contest in a hunt for more diversity among writers as well as in the stories.

ABOUT THE AWARD

TU BOOKS , the fantasy, science fiction, and mystery imprint of LEE and LOW BOOKS, announces their first annual New Visions Award .

The New Visions Award will be given for a middle grade or young adult

fantasy, science fiction, or mystery novel by a writer of color. Authors

who have not previously had a middle grade or young adult novel

published are eligible.

The Award winner will receive a cash grant of $1000 and our standard

publication contract, including our basic advance and royalties for a

first time author. An Honor Award winner will receive a cash grant of

$500. Manuscripts will be accepted through October 30, 2012. See the full submissions guidelines here .

The

New Visions Award was established to help more authors of color break

into publishing and begin long, successful careers, while also bringing

more diverse stories to speculative fiction. The award is modeled after

Lee and Low's successful New Voices Award , which was established in 2000 and is given annually to a picture book written by an unpublished author of color.

Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Published on August 20, 2012 10:22

August 13, 2012

SCBWI Debuts On-The-Verge Emerging Voices Award

PRESS RELEASE:

August 5, 2012, LOS ANGELES — The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) announced the creation of the On-The-Verge Emerging Voices Award at their 41st Annual Conference in Los Angeles. The annual award, established by SCBWI and funded by Martin and Sue Schmitt, will be given to two writers or illustrators who are from ethnic and/or cultural backgrounds that are traditionally under-represented in children’s literature in America and who have a ready-to-submit completed work for children. The purpose of the grant is to inspire and foster the emergence of diverse writers and illustrators of children’s books.

The work will be judged by an SCBWI committee and two winners will each receive an all-expenses paid trip to the SCBWI Winter Conference in New York to meet with editors and agents, a press release to all publishers, a year of free membership to SCBWI, and an SCBWI mentor for a year. Deadline for submission is November 15, 2012. The winners will be announced December 15, 2012. The On-The-Verge Emerging Voices Award will be presented at the 2013 SCBWI Winter Conference in New York. Submission guidelines and information can be found at www.scbwi.org under Awards and Grants.

The award was inspired in part by the SCBWI’s increasing efforts to foster under-represented voices in children’s literature. According to SCBWI Executive Director Lin Oliver, “Every child should have the opportunity to experience many and diverse of points of view. SCBWI is proud to contribute to this all-important effort to bring forth new voices.”

The grant was made possible through the generosity of Sue and Martin Schmitt of the 455 Foundation who state: "While our country is made up of beautifully varied cultures and ethnicities, too few are represented in the voices of children's books. We hope to encourage participation by those not well represented, and look forward to having these stories widely enjoyed by all children."

About Martin and Sue Schmitt

Martin and Sue Schmitt are the founders of We Can Build an Orphanage, sponsoring the Kay Angel orphanage in Jacmel, Haiti. The organization was established in 2007 with the mission to provide a home and education for abandoned children infected with or affected by AIDS in Jacmel, Haiti. The Schmitt’s generous and continuous efforts to support SCBWI’s long-term goals also co-sponsored the 2007 Global Voices Program, which highlighted Mongolian artists and authors. To find out more information about the Kay Angel orphanage please visit www.kayangel.org.

About SCBWI

Founded in 1971, the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators is one of the largest existing writers’ and illustrators’ organizations, with over 22,000 members worldwide. It is the only organization specifically for those working in the fields of children’s literature, magazines, film, television, and multimedia. The organization was founded by Stephen Mooser (President) and Lin Oliver (Executive Director), both of whom are well-published children’s book authors and leaders in the world of children’s literature. For more information about the On-The-Verge Emerging Voices Award, please visit www.scbwi.org, and click “Awards and Grants.”

Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

August 5, 2012, LOS ANGELES — The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) announced the creation of the On-The-Verge Emerging Voices Award at their 41st Annual Conference in Los Angeles. The annual award, established by SCBWI and funded by Martin and Sue Schmitt, will be given to two writers or illustrators who are from ethnic and/or cultural backgrounds that are traditionally under-represented in children’s literature in America and who have a ready-to-submit completed work for children. The purpose of the grant is to inspire and foster the emergence of diverse writers and illustrators of children’s books.

The work will be judged by an SCBWI committee and two winners will each receive an all-expenses paid trip to the SCBWI Winter Conference in New York to meet with editors and agents, a press release to all publishers, a year of free membership to SCBWI, and an SCBWI mentor for a year. Deadline for submission is November 15, 2012. The winners will be announced December 15, 2012. The On-The-Verge Emerging Voices Award will be presented at the 2013 SCBWI Winter Conference in New York. Submission guidelines and information can be found at www.scbwi.org under Awards and Grants.

The award was inspired in part by the SCBWI’s increasing efforts to foster under-represented voices in children’s literature. According to SCBWI Executive Director Lin Oliver, “Every child should have the opportunity to experience many and diverse of points of view. SCBWI is proud to contribute to this all-important effort to bring forth new voices.”

The grant was made possible through the generosity of Sue and Martin Schmitt of the 455 Foundation who state: "While our country is made up of beautifully varied cultures and ethnicities, too few are represented in the voices of children's books. We hope to encourage participation by those not well represented, and look forward to having these stories widely enjoyed by all children."

About Martin and Sue Schmitt

Martin and Sue Schmitt are the founders of We Can Build an Orphanage, sponsoring the Kay Angel orphanage in Jacmel, Haiti. The organization was established in 2007 with the mission to provide a home and education for abandoned children infected with or affected by AIDS in Jacmel, Haiti. The Schmitt’s generous and continuous efforts to support SCBWI’s long-term goals also co-sponsored the 2007 Global Voices Program, which highlighted Mongolian artists and authors. To find out more information about the Kay Angel orphanage please visit www.kayangel.org.

About SCBWI

Founded in 1971, the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators is one of the largest existing writers’ and illustrators’ organizations, with over 22,000 members worldwide. It is the only organization specifically for those working in the fields of children’s literature, magazines, film, television, and multimedia. The organization was founded by Stephen Mooser (President) and Lin Oliver (Executive Director), both of whom are well-published children’s book authors and leaders in the world of children’s literature. For more information about the On-The-Verge Emerging Voices Award, please visit www.scbwi.org, and click “Awards and Grants.”

Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Published on August 13, 2012 11:07

July 31, 2012

2012 South Asia Book Award for Children’s and Young Adult Literature

2012 South Asia Book Award for Children's and Young Adult Literature Winners

Same, Same but Different by Jenny Sue Kostecki-Shaw (Henry Holt and Company, 2011). Pen Pals Elliot and Kailash discover that even though they live in different countries—America and India—they both love to climb trees, own pets, and ride school buses (Grade 5 and under).

Island’s End by Padma Venkatraman (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, division of Penguin Young Readers Group, 2011). A young girl trains to be the new spiritual leader of her remote Andaman Island tribe, while facing increasing threats from the modern world (Grade 6 and above).

2012 Honor Books

Sita’s Ramayana by Samhita Arni, illustrations by Moyna Chitrakar (Groundwood Books, 2011). The Ramayana, one of the greatest legends of ancient India, is presented in the form of a visually stunning and gripping graphic novel, told from the perspective of the queen, Sita (Grade 6 and above).

Following My Paint Brush by Dulari Devi and Gita Wolf (Tara Books Pvt. Ltd, 2010). Following My Paint Brush is the story of Dulari Devi, a domestic helper who went on to become an artist in the Mithila style of folk painting from Bihar, eastern India (Grade 5 and under).

Following My Paint Brush by Dulari Devi and Gita Wolf (Tara Books Pvt. Ltd, 2010). Following My Paint Brush is the story of Dulari Devi, a domestic helper who went on to become an artist in the Mithila style of folk painting from Bihar, eastern India (Grade 5 and under).

No Ordinary Day by Deborah Ellis (Groundwood Books, 2011). Valli has always been afraid of the people with leprosy living on the other side of the train tracks in the coal town of Jharia, India, so when a chance encounter with a doctor reveals she too has the disease, Valli rejects help and begins a life on the streets. (Grade 6 and above).

Small Acts of Amazing Courage by Gloria Whelan (Simon & Schuster, 2011). In 1919, independent-minded Rosalind lives in India with her English parents, and when they fear she has fallen in with some rebellious types who believe in Indian self-government, she is sent "home" to London, where she has never been before and where her older brother died, to stay with her two aunts (Grade 6 and above).

2012 Highly Commended Books

Beyond Bullets: A Photo Journal of Afghanistan by Rafal Gerszak with Dawn Hunter (Annick Press, 2011). Award-winning photographer Rafal Gerszak spent a year embedded with the American troops in Afghanistan to bear witness to its people, culture, and the impact of war (Grade 6 and above).

The Wise Fool: Fables from the Islamic World by Shahrukh Husain, illustrations by Micha Archer (Barefoot Books, 2011). Meet Mulla Nasruddin, a legendary character whose adventures and misadventures are enjoyed across the Islamic world (Grade 5 and under).

The Grand Plan to Fix Everything by Uma Krishnaswami (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon and Schuster Children’s Publishing Division, 2011). Eleven-year-old Dini loves movies, and so when she learns that her family is moving to India for two years, her devastation over leaving her best friend in Maryland is tempered by the possibility of meeting her favorite actress, Dolly Singh (Grade 6 and up).

Karma by Cathy Ostlere (Razorbill, Penguin Group, 2011). Written in free verse poems in a diary format, this novel straddles two countries and the clash of Indian cultures in the tale of 15-year-old Maya (Grade 6 and up).

Words in the Dust by Trent Reedy (Scholastic Inc., 2011). Zulaikha, a thirteen-year-old girl in Afghanistan, faces a series of frightening but exhilarating changes in her life as she defies her father and secretly meets with an old woman who teaches her to read, her older sister gets married, and American troops offer her surgery to fix her disfiguring cleft lip (Grade 6 and up).

The 2012 South Asia Book Award Ceremony will be held in Madison, Wisconsin on Saturday, October 13, 2012. The SABA Award is sponsored by the South Asia National Outreach Consortium. Funded by the US Department of Education Title VI, Member National Resource Centers.

Submissions for the 2013 South Asia Book Award

Rationale

In recent years an increasing number of high-quality children's and young adult fiction books have appeared that portray South Asia or South Asians living abroad. To encourage and commend authors and publishers who produce such books, and to provide teachers with recommendations for classroom use, the South Asia National Outreach Consortium (SANOC) will offer a yearly book award to call attention to outstanding works on South Asia.

Criteria

Up to two awards will be given in recognition of a recently published work of fiction, non-fiction, poetry or folklore, from early childhood to secondary reading levels, published in English (translations into English will also be accepted) which accurately and skillfully portrays South Asia or South Asians in the diasporas, that is the experience of individuals living in South Asia, or of South Asians living in other parts of the world. The culture, people, or heritage of South Asia should be the primary focus of the story. The countries and islands that make up South Asia are: Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Maldives, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and the region of Tibet. We will also consider stories that take place in the Caribbean Islands that focus on a South Asian subject. In determining the award, books will be judged for: 1) quality of story; 2) cultural authenticity; and 3) potential for classroom use.

Eligibility

Eligible books include those that are published in the US, UK, Canada, and countries in South Asia. Consideration will be given to the ease with which school teachers and librarians in the United States would be able to order multiple copies. Books may be submitted by publishers or individuals, although the judges may consider any eligible book that comes to their attention.

Process

To nominate a 2012 copyright title, publishers or individuals are invited to submit review copies to the award committee by December 31, 2012. There is no entry fee. Committee members will review the nominated books individually and will consult reviews in major publishing/library journals. Contact Rachel Weiss, Award Coordinator, at (608) 262-9224 or saba@southasiabookaward.org.Come visit me on the Fire Escape!

Published on July 31, 2012 06:31