Timothy Ferriss's Blog, page 105

May 6, 2014

The Tim Ferriss Podcast, Episode 4: Ryan Holiday

“The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.” — Marcus Aurelius

This post includes:

- Sponsor intro (please visit them)

- Episode description

- Quick favor

- Show notes and tons of useful links, including mentioned books and documentaries

- Non-iTunes options for listening

This episode of The Tim Ferriss Show is sponsored by HipDial, which I’ve been a fan of for ages.

I use HipDial for conference calls: no stupid PIN numbers, no hitting #, and you get a text when people join, so you don’t have to wait. It’s rocks–try it for a free month, and you’ll never go back.

Now, on to the main event…

My guest is Ryan Holiday, who became Director of Marketing at American Apparel at age 21 (!). He’s a beast.

Since dropping out of college at 19 to apprentice under strategist Robert Greene (author of The 48 Laws of Power), Ryan has advised many New York Times bestselling authors and mega-multi-platinum musicians. He is a master of the media, and he knows how to build massive buzz while responding to unexpected crises. He can compete or counterpunch with the best.

I hired Ryan to help with the launches of The 4-Hour Body and The 4-Hour Chef. His unorthodox approaches always impress me.

I loved his new book (The Obstacle Is The Way) so much that I bought the audiobook format and produced it with him. It is the newest addition to The Tim Ferriss Book Club.

In this episode, we discuss dozens of topics, including the real-world strategies he uses to thrive (not just survive) when the world is exploding around him.

And…want to win some cool stuff today? Tweet out your favorite quote or line from this episode, using the following format, and I’ll pick a few of my favorites for prizes:

“[Insert quote]” More: https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/the-tim-ferriss-show/id863897795?mt=2 #TFS”

To encourage other people to retweet, try and keep your entire tweet to 125 characters or fewer. The iTunes link above will be automatically shortened.

Deadline is 8:30pm PST.

QUICK FAVOR – If you haven’t already, can you pretty please:

1) Leave a review of the podcast on iTunes here?

2) Vote as “helpful” the reviews you most agree with? Here’s the link. The vast majority are 5 stars (290 out of 333), but there’s some wild Haterade, too, if that’s your thing.

Show Notes for Episodes 4 (Thanks, Ian!)

The surprising story of how Ryan was introduced to stoicism by Dr. Drew

What makes a “quake book”?

How Marcus Aurelius helped Ryan survive a tough breakup

About esoteric philosophical ideas that are excellent tools in the modern world

Deconstructing the “Big 3″ stoics – Seneca | Epictetus | Aurelius

Is stoicism compatible with material or financial success, or are they completely at odds with one another?

Tim’s strategy for developing connections in Silicon Valley

Cultivating advantageous mentorships with peak performers

The story of Benjamin Franklin’s lending library…

What Ryan credits for his ability to “get shit done.”

What a day in the life of Ryan Holiday looks like (deflecting meeting requests, etc.)

Why e-mail can save time compared to a phone call

The most common mistake that new writers make

Delving into the writing process

How Ryan approaches goal setting and financial security

Friend curation, and the factors that guide Ryan’s decision making

Rapid-fire questions:

Ryan’s fight entrance song?

One thing he would change about himself?

When he thinks of the word “successful,” who comes to mind, and why?

If he could study any expert in the world, who would it be and why?

Advice to his younger self?

What Ryan orders at the bar?

Who should drop out of college versus who should stay in college

And much, much more…

SOME LINKS FROM EPISODE 4

Maker vs. Manager by Paul Graham

Who Ryan Follows on Twitter:

Fake Jeff Jarvis

FelixSolomon

Media Redefined by Jason Hirschhorn

MariaPapova of BrainPickings

Ryan’s favorite blogs:

Feedly

Ta-Nehisi Coate’s blog

Mark Cuban’s blog

Ryan’s Favorite Reddits:

Stoicism | Philosophy | History Porn | Ask Historians

Today I Learned | First World Problems | Reddit Books

BOOKS MENTIONED IN EPISODE 4

Marcus Aurelius – Meditations: A Translation

Epictitus – The Art of Living

Nicholas Nassim-Taleb - Scholar, Statistician

The Black Swan

Fooled by Randomness

Antifragile

Benjamin Franklin by Ron Chernow

Titan: The Life of John D Rockefeller by Ron Cherow

How to Live by Sarah Bakewell

The Fish that Ate the Whale: The Life and Time of the Banana King by Rich Cohen

Tough Jews by Rich Cohen

Edison: A Biography by Matthew Josephson

Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph over Adversity by Brooks D. Simpson

John McPhee – Non-Fiction Writer (Pulitzer Prize Winner)

Oranges

Levels of the Game

The Survival of the Bark Canoe

Plymouth Rock (Free Online)

The Control of Nature

Giving Good Weight

The War of Art by Steven Pressfield

DOCUMENTARIES MENTIONED FROM EPISODE 4

Fog of War: Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara

An Unauthorized Guide to The Known Unknown about Donald Rumsfeld

The Wall of Sound about Phil Spector

Every Ken Burns Documentary (10 hrs. on Civil War & 10 hrs. on National Park System)

Connect with Ryan Holiday: Twitter | Website | Thought Catalogue | Observer

NO ITUNES? NO PROBLEM:

Just listen on Stitcher, or you can listen using the player below –

May 5, 2014

The Random Show, Episode 24: Porn Attacks, Eating Insect Protein, Tech Finds, and More

There are dozens of topics covered in this tea-infused, bromantic episode of scatterbrained nonsense.

Like what? Well: porn (including select picks), taking an “alcohol vacation,” fixing low testosterone, the wonders of insect protein, start-up talk, and much more. O-tanoshimi dane!

One special offer:

If you sign up as one of the first 100 people in this Google form (sorry, US only), we will mail you one free Exo cricket protein bar. They are amaze-balls. Here is the link.

This edition of The Random Show was recorded and edited by Graham Hancock(@grahamhancock). For all previous episodes, including the epic China Scam episode,click here.

As always, if you’re the first to leave complete show notes in the comments, I’ll happily give you credit and link to your site here in the post.

Enjoy!

Let us know what you’d like us to tackle in the next show…

April 27, 2014

The Tim Ferriss Podcast, Episode 3: Kelly Starrett and Dr. Justin Mager

It’s my first podcast threesome! [blush]

THE TIM FERRISS SHOW, EPISODE 3:

This episode features two incredible guests: Dr. Justin Mager and Kelly Starrett. We all drink wine and get crazy.

Dr. Mager is my personal doctor and has helped me with dozens of my crazy experiments, complete with blood testing and next-generation tracking. He’s brilliant (and hilarious).

Kelly Starrett is one of the top Crossfit coaches in the world, and one of my favorite PTs and performance trainers. His clients include Olympic gold medalists, Tour de France cyclists, world and national record holders in Olympic lifting and powerlifting, Crossfit Games medalists, ballet dancers, and elite military personnel. If you’re interested in taking your body or brain to the next level, or attempting to become the guy from Limitless, this episode is for you.

Enjoy!

And…want to win some cool stuff today? Tweet out your favorite quote or line from this episode, using the following format, and I’ll pick a few of my favorites for prizes:

“[Insert quote]” More: https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/the-tim-ferriss-show/id863897795?mt=2 #TFS”

To encourage other people to retweet you, try and ensure your entire Tweet is 120 characters or less. The iTunes link above will be automatically shortened.

If you haven’t already, please subscribe to the podcast on iTunes! My iTunes rank — largely determined by subscriber count — is critical for recruiting future guests. Other options for download are the end of this post, but iTunes (here) really helps me out, even if just for the first few episodes. Help me make this podcast as strong as possible, and click subscribe here!

If you’d like a teaser of Episode 3, some of the subjects we cover are below. Learn more about Kelly at MobilityWOD and through his Twitter account:

Defining a “performance whore”

The potent combination that is Justin Mager

What makes people “well” and what makes people thrive

Mixing passions for endocrinology and eastern philosophy

How chakras described in Ayurvedic medicine correspond to nerve plexuses and endocrine glands

How Justin Mager changes lives by exploring the body as a whole

Experimenting on the fringes of physiology and what limits can be pushed

Working with high-end athletes and military to exceed supposed “optimal” performance

Blood testing is a snapshot, not a overall description of health — how do you improve it? What do you measure?

Delving into the effects of travel on circadian rhythms, and how to correct problems

Exploring the Quantified Self (QS) movement and Kevin Kelly

Testing quality of sleep

Why science isn’t the cause-and-effect master of the universe, or shouldn’t be viewed as such

Pattern recognition and “chunking” for improved talent acquisition

The diverse role of genetics; what can be changed and what cannot

The health and performance implications of testosterone, boners, sleep, and more

Mattress selection from the mobility expert (Kelly)

Hacking the nervous system for rejuvenating sleep, utilizing body temperature as a tool

Rebooting the parasympathetic nervous system

“Supple Leopard” morning rituals

Kelly’s test of functional mobility

How pain tolerance, mobility, and movement come together

Common qualities of top physicians, coaches, and bio-hackers, and how you can emulate them…

###

For Android users, this podcast can also be found on Stitcher.

Just want the plain old RSS feed? Here it is! http://feeds.feedburner.com/thetimferrissshow

Users of Pocket Casts (and similar apps) can copy the Feedburner link above, then paste it in the app’s search bar. It’ll take you straight to the good stuff.

Hai!

April 22, 2014

The Tim Ferriss Podcast is Live! Here Are Episodes 1 and 2

Fuckin’ A–it’s finally here!

After fantasizing about starting a podcast for nearly two years, after being asked hundreds of times, The Tim Ferriss Show is now live.

Sometimes you have to stop over-thinking things, bite the bullet, and figure it out as you go.

To launch, I’ve posted two episodes that are vastly different. They are available on iTunes and, for Android folks, Stitcher.

I have an important favor to ask, which I don’t do often:

1) Please listen to one or both episodes.

2) Then, PLEASE leave a review on iTunes.

I will read EVERY review and, based on that feedback, I’ll either stop or keep doing this podcast.

If you seem to like them, I promise to do at least 6 total episodes in the next 1-2 months. And trust me: I have some amazing people lined up and ready to go. Constructive criticism and suggestions for improvement are welcome, whether on iTunes or in the comments below.

All that said, here are the first two episodes! I really hope you enjoy them.

I consider Kevin Rose one of the best “stock pickers” in the startup world. He can predict even non-tech trends with stunning accuracy.

Kevin is a tech entrepreneur who co-founded Digg, Revision3 (sold to Discovery Channel), Pownce, and Milk (sold to Google). Since 2012, he is a venture partner at Google Ventures. He’s also a hilarious dude, and this episode involves heavy drinking.

In this finding-my-feet episode, Kevin and I get down on a bottle of Gamling and McDuck while discussing, among dozens of topics: why Kevin would love to work at McDonald’s, how he kicked my ass on the Twitter deal, and — just a wee tad — biohacking.

Dive in, folks!

It’s the first episode of The Tim Ferriss Show! Listen to it here, and please subscribe!

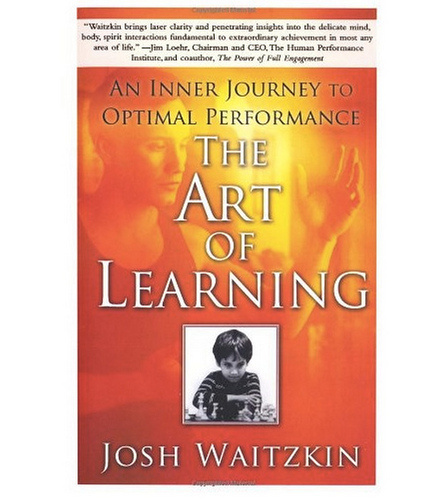

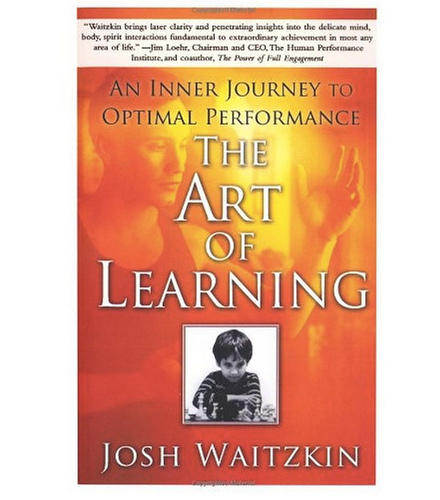

Josh Waitzkin was the basis for the book and movie Searching for Bobby Fischer.

Considered a chess prodigy, he has perfected learning strategies that can be applied to anything, including his other loves of Brazilian jiu-jitsu (he’s a black belt under phenom Marcelo Garcia) and Tai Chi Push Hands (he’s a world champion). These days, he spends his time coaching the world’s top performers, whether Mark Messier, Cal Ripken Jr., or hedgefund managers. I initially met Josh through his incredible book, The Art of Learning, which I loved so much that I helped produce the audiobook (download here, at Audible or DRM-free Gumroad).

This episode is DEEP, in the best way possible. Josh will blow your mind.

And for a change from Episode 1, I’m totally sober. I’d be curious to know which Tim you prefer.

Listen to it here, and please subscribe!

Show Notes for Episodes 1 and 2

Special thanks to my friend Ian for helping with show notes. Much obliged, kind sir.

These notes only partially cover the conversations, but they will give you a taste.

EPISODE 1: KEVIN ROSE

What makes a good wine bar?

The story of Kevin Rose: Growing up in Vegas, starting Digg, joining Google Ventures, and beyond

What makes Kevin Rose so good at predicting what’s next, spotting trends

The characteristics of winners. What makes a successful angel investor?

Hear the story of Odeo – The company that birthed Twitter

Tips on choosing angel investments

“What new app will find itself on the front screen of your iPhone?”

Dissecting the success of Philip Rosedale, Elon Musk and — the “Oracle of Silicon Valley” — Reid Hoffman

How to say no to an investment or pitch

Experiences and lessons learned running the roller coaster of Digg

Where is Kevin Rose world-class? Which skills define his success?

The M7 chip on iPhone – An opportunity to build new apps

Learn more about My Basis, a biometric company that Tim invested in [Update: sold to Intuit for $100M]

Why Kevin wants to get a job at McDonald’s

Ideas and suggestions for the podcast. Where should it go, and how should it be different?

SOME LINKS FROM EPISODE 1

Learn more about Digg

Nextdoor – Private Social Network for your Neighborhood

Watch the Philip Rosedale interview on Foundation

Pick up Venture Deals by Brad Feld

Check out Hotel Biron – Kevin’s fave tiny wine bar in San Francisco

Visit Zuni Cafe – Get the dry-brined roasted chicken

Learn more about Apple’s new M7 Chip

Get health insights from MyBasis

Any many more….

Connect with Kevin Rose: Instagram | Twitter | Website

EPISODE 2: JOSH WAITZKIN

Show Notes:

The origins of The Art of Learning.

What it takes to play 30-50 games of chess simultaneously (!).

About Josh’s focus on moving from world-class to world champion. How to cross the gap between the two

The many dimensions of Josh Waitzkin’s creative life:

Family

JW Foundation – The Art of Learning Project

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) school with Marcelo Garcia

Consulting for “Master of the Universe”-type financiers; what commonalities the best have

About the learning (and UNlearning) processes that distinguish the good from the great and from the elite

Insights on the strategic movement from Tai Chi to BJJ

About the profound kinesthetic intelligence of Marcelo Garcia and how he uses it to “navigate the world”

A deep understanding of what makes world-class performers tick and thrive

“If you can really train people to get systematic about nurturing their creative process, it’s unbelievable what can happen. Most of that work relates to getting out of your own way at a very high level. It’s unlearning, it’s the constant practice of subtraction, reducing friction.” – Josh Waitzkin

Strategies for aligning peak energy periods with peak creativity to achieve a relentless, proactive lifestyle

On Hemingway’s creative writing process:

End the workday with something left to write

Release your mind from the work – Let Go

Understanding cognitive biases

Understanding how to use specific questions for deconstruction (e.g. “Who’s good at this who shouldn’t be?”)

Core themes/habits that Josh teaches to top performers:

Meditation | Journaling | “Undulation” (Capacity to turn drive on and off)

How Josh Waitzkin meditates

Meditation styles: contemplative Buddhist sitting meditation, Tai Chi and moving meditation.

What Josh’s morning rituals look like

Why you should study the artists rather than the art critics.

Remember to love .

“The hero and the coward both feel the same thing, but the hero uses his fear and projects it onto his opponent, while the coward runs.” – Cus D’Amato, original trainer of Mike Tyson

Links:

JW Foundation – The Art of Learning Project

Check out Hemingway on Good Reads

Learn more about BJJ school of Marcelo Garcia

Identify your own biases: List of Cognitive Biases

Check out the article Tim mentioned: Bridgewater Associates founder, Ray Dalio, credits transcendental meditation for his success

“One of the things we have to be wary in life is studying the people who study the artists, as opposed to the artists themselves” – Josh Waitzkin

The Waitzkin Library:

On the Road – Jack Kerouac

Dharma Bums – Jack Kerouac

Tao te Ching – Lao Tzu Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English Translation

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance – Robert M. Pirsig

Shantaram – Gregory David Roberts

For Whom the Bell Tolls – Ernest Hemingway

Green Hills of Africa – Ernest Hemingway

Complete Collection of Short Stories – Ernest Hemingway

Old Man and the Sea – Ernest Hemingway

A Moveable Feast – Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway on Writing - Larry W. Phillips

March 24, 2014

The Tim Ferriss Experiment Cometh! All 13 Episodes At Once, House of Cards-Style

Let’s get this party started!

For months now, I’ve wanted show you all of my TV episodes.

Over the last year, the team at ZPZ (the production company behind Anthony Bourdain) and Turner Broadcasting have helped me capture incredible footage and characters all over the country. I’m thrilled with every episode.

Alas, for reasons I won’t bore you with, the TV broadcasting puzzle piece is taking ages to sort out. I’ve been fighting hard behind the scenes, and it’s been a sumnabitch process for an impatient Long Island boy (me).

The waiting has driven me absolutely insane. I’ve felt a lot like this:

But…no más waiting already!

Enough. While the entertainment folks are sussing out cable details, I’d like to give you everything — and I mean EVERYTHING — digitally.

Turner’s all for it. This world is a changin’, and distribution is changing with it.

ON MAY 27, ALL 13 EPISODES WILL BE RELEASED ON ITUNES SIMULTANEOUSLY.

In each episode, I team up with world-class teachers to “hack” a different skill….then I get thrown through a gauntlet of tests. Sometimes I do well, othertimes I face-plant and decimate myself. You get to see all the struggles, nervous breakdowns, and little breakthroughs. It ain’t always pretty, but it’s real.

Here are some of the topics I jump into:

Music and drumming

Rally car racing

Language learning

Brazilian jiu-jitsu (and chess) — ouch.

Parkour — super, double ouch.

High-stakes poker (with real money)

Tactical gun fighting

Dating and the pick-up game

Building a business in one week (I co-teach a student)

Golf

Long-distance swimming (I co-teach a student)

Surfing

And the mysterious finale episode…

And another thing…

One of the things that bugs me most about TV is that five days of shooting gets cut down to 30 minutes. In reality, it’s around 21:30 after subtracting commercials. Whaaaa?! “Isn’t that a waste?” you ask. Yes, it’s a maddening amount of great footage that ends up on the cutting room floor.

I want to give you more.

So…

If you’ve bought — or buy — an iTunes season pass (click “View in iTunes” here to purchase), more good news: you’ll get a ton of bonus footage. Current estimates are 10+ minutes of extras per episode, and I’m fighting to release much more footage into the wild, hopefully hours and hours.

If you can’t use iTunes or can’t afford to pay, here’s the solution: Each week after the May 27th launch, one episode will be released on YouTube for free viewing. It won’t contain bonus footage, and you’ll have to wait 3+ months to see the whole season, but you’ll be able to see them all.

If you’d like a sneak peek, the first episode can be watched here for free.

Much more coming soon, and thank you for your patience! It’s been a long road for everyone. Phew.

March 21, 2014

12 Rules for Learning Foreign Languages in Record Time — The Only Post You’ll Ever Need

Preface by Tim Ferriss

I’ve written about how I learned to speak, read, and write Japanese, Mandarin, and Spanish. I’ve also covered my experiments with German, Indonesian, Arabic, Norwegian, Turkish, and perhaps a dozen others.

There are only few language learners who dazzle me, and Benny Lewis is one of them.

This definitive guest post by Benny will teach you:

How to speak your target language today.

How to reach fluency and exceed it within a few months.

How to pass yourself off as a native speaker.

And finally, how to tackle multiple languages to become a “polyglot”—all within a few years, perhaps as little as 1-2.

It contains TONS of amazing resources I never even knew existed, including the best free apps and websites for becoming fluent in record time. Want to find a native speaker to help you for $5 per hour? Free resources and memory tricks? It’s all here.

This is a post you all requested, so I hope you enjoy it!

Enter Benny

You are either born with the language-learning gene, or you aren’t. Luck of the draw, right? At least, that’s what most people believe.

I think you can stack the deck in your favor. Years ago, I was a language learning dud. The worst in my German class in school, only able to speak English into my twenties, and even after six entire months living in Spain, I could barely muster up the courage to ask where the bathroom was in Spanish.

But this is about the point when I had an epiphany, changed my approach, and then succeeded not only in learning Spanish, but in getting a C2 (Mastery) diploma from the Instituto Cervantes, working as a professional translator in the language, and even being interviewed on the radio in Spanish to give travel tips. Since then, I moved on to other languages, and I can now speak more than a dozen languages to varying degrees between conversational and mastery.

It turns out, there is no language-learning gene, but there are tools and tricks for faster learning…

As a “polyglot”—someone who speaks multiple languages—my world has opened up. I have gained access to people and places that I never otherwise could have reached. I’ve made friends on a train in China through Mandarin, discussed politics with a desert dweller in Egyptian Arabic, discovered the wonders of deaf culture through ASL, invited the (female) president of Ireland to dance in Irish (Gaeilge) and talked about it on live Irish radio, interviewed Peruvian fabric makers about how they work in Quechua, interpreted between Hungarian and Portuguese at a social event… and well, had an extremely interesting decade traveling the world.

Such wonderful experiences are well within the reach of many of you.

Since you may be starting from a similar position to where I was (monolingual adult, checkered history with language learning, no idea where to start), I’m going to outline the tips that worked best for me as I went from zero to polyglot.

This very detailed post should give you everything you need to know.

So, let’s get started!

#1 – Learn the right words, the right way.

Starting a new language means learning new words. Lots of them.

Of course, many people cite a bad memory for learning new vocab, so they quit before even getting started.

But–here’s the key–you absolutely do not need to know all the words of a language to speak it (and in fact, you don’t know all the words of your mother tongue either).

As Tim pointed out in his own post on learning any language in 3 months, you can take advantage of the Pareto principle here, and realize that 20% of the effort you spend on acquiring new vocab could ultimately give you 80% comprehension in a language—for instance, in English just 300 words make up 65% of all written material. We use those words a lot, and that’s the case in every other language as well.

You can find pre-made flash card “decks” of these most frequent words (or words themed for a subject you are more likely to talk about) for studying on the Anki app (available for all computer platforms and smartphones) that you can download instantly. Good flashcard methods implement a spaced repetition system (SRS), which Anki automates. This means that rather than go through the same list of vocabulary in the same order every time, you see words at strategically spaced intervals, just before you would forget them.

Tim himself likes to use color-coded physical flashcards; some he purchases from Vis-Ed, others he makes himself. He showed me an example when I interviewed him about how he learns languages in the below video.

Though this entire video can give you great insight into Tim’s language learning approach, the part relevant to this point is at 27:40 (full transcript here).

)

#2 – Learn cognates: your friend in every single language.

Believe it or not, you already—right now—have a huge head start in your target language. With language learning you always know at least some words before you ever begin. Starting a language “from scratch” is essentially impossible because of the vast amount of words you know already through cognates.

Cognates are “true friends” of words you recognize from your native language that mean the same thing in another language.

For instance, Romance languages like French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and others have many words in common with English. English initially “borrowed them” from the Norman conquest of England, which lasted several hundreds of years. Action, nation, precipitation, solution, frustration, tradition, communication, extinction, and thousands of other -tion words are spelled exactly the same in French, and you can quickly get used to the different pronunciation. Change that -tion to a -ción and you have the same words in Spanish. Italian is -zione and Portuguese is -ção.

Many languages also have words that share a common (Greek/Latin or other) root, which can be spelled slightly differently, but that you’d have to try hard not to recognize, such as exemple, hélicoptère (Fr), porto, capitano (Italian) astronomía, and Saturno (Spanish). German goes a step further and has many words from English’s past that it shares.

To find common words with the language you are learning, simply search for “[language name] cognates” or “[language name] English loan words” to see words they borrowed from us, and finally “[language name] words in English” to see words we borrowed from them.

That’s all well and good for European languages, but what about more distant ones?…

Well, it turns out that even languages as different as Japanese can have heaps of very familiar vocabulary. To show you what I mean, have a listen to this song (to the tune of Animaniac’s “Nations of the World”), which is sung entirely in Japanese, and yet you should understand pretty much everything that I and the other Japanese learners are singing:

)

This is because many languages simply borrow English words and integrate them into the new language with altered pronunciation or stress.

So to make my life easy when I start learning a language, one of the first word lists I try to consume is a list of “cognates,” or “English loan words,” which can be found quickly for pretty much any language.

#3 – Interact in your language daily without traveling.

Another reason (or excuse, depending on how you look at it) people cite for not learning languages is that they can’t visit a country where it’s a native language. No time, no money, etc.

Take it from me—there is nothing “in the air” in another country that will magically make you able to speak their language. I’ve done a lot of experiments to prove this (e.g. learning Arabic while living in Brazil).

I’ve met countless expats who lived abroad for years without learning the local language. Living abroad and being immersed is not the same thing. If you need to hear and use a language consistently to be immersed, can’t virtual immersion be just as effective? Of course. Technology makes it possible for immersion to come to you, and you don’t even have to buy a plane ticket.

To hear the language consistently spoken, you can check out TuneIn.com for a vast selection of live-streamed radio from your country of choice. The app (free) also has a list of streamed radio stations ordered by language.

To watch the language consistently, see what’s trending on Youtube in that country right now. Go to that country’s equivalent URL for Amazon or Ebay (amazon.es, amazon.fr, amazon.co.jp, etc.) and buy your favorite TV series dubbed in that language, or get a local equivalent by seeing what’s on the top charts. You may be able to save shipping costs if you can find one locally that includes dubbing in the appropriate language. Various news stations also have plenty of video content online in specific languages, such as France24, Deutsche Welle, CNN Español, and many others.

To read the language consistently, in addition to the news sites listed above, you can find cool blogs and other popular sites on Alexa’s ranking of top sites per country.

And if full-on immersion isn’t your thing yet, there’s even a plugin for Chrome that eases you into the language by translating some parts of the sites you normally read in English, to sprinkle the odd word into your otherwise English reading.

#4 – Skype today for daily spoken practice.

So you’ve been listening to, watching, and even reading in your target language—and all in the comfort of your own home. Now it’s time for the big one: speaking it live with a native.

One of my more controversial pieces of advice, but one that I absolutely insist on when I advise beginners, is that you must speak the language right away if your goals in the target language involve speaking it.

Most traditional approaches or language systems don’t work this way, and I think that’s where they let their students down. I say, there are seven days in a week and “some day” is not one of them.

Here’s what I suggest instead:

Use the pointers I’ve given above to learn some basic vocabulary, and be aware of some words you already know. Do this for a few hours, and then set up an exchange with a native speaker—someone who has spoken that language their whole life. You only have to learn a little for your first conversation, but if you use it immediately, you’ll see what’s missing and can add on from there. You can’t study in isolation until you are vaguely “ready” for interaction.

In those first few hours, I’d recommend learning some pleasantries such as “Hello,” “Thank you,” “Could you repeat that?” or “I don’t understand,” many of which you will find listed out here for most languages.

But wait—where do you find a native speaker if you aren’t in the country that speaks that language?

No problem! Thousands of native speakers are ready and waiting for you to talk to them right now. You can get private lessons for peanuts by taking advantage of currency differences. My favorite site for finding natives is italki.com (connect with my profile here), where I’ve gotten both Chinese and Japanese one-on-one Skype-based lessons for just $5 an hour.

If you still think you wouldn’t be ready on day one, then consider this: starting on Skype allows you to ease yourself in gently by having another window (or application, like Word) open during your conversation, already loaded with key words that you can use for quick reference until you internalize them. You can even reference Google Translate or a dictionary for that language while you chat, so you can learn new words as you go, when you need them.

Is this “cheating”? No. The goal is to learn to be functional, not to imitate old traditional methods. I’ve used the above shortcuts myself, and after learning Polish for just one hour for a trip to Warsaw to speak at TEDx about language learning, I was able to hold up a conversation (incredibly basic as it was) in Polish for an entire half hour.

I consider that a win.

)

#5 – Save your money. The best resources are free.

Other than paying for the undivided attention of a native speaker, I don’t see why you’d need to spend hundreds of dollars on anything in language learning. I’ve tried Rosetta Stone myself and wasn’t impressed.

But there is great stuff out there. A wonderful and completely free course that keeps getting better is DuoLingo - which I highly recommend for its selection of European languages currently on offer, with more on the way. To really get you started on the many options available to help you learn your language without spending a penny, let me offer plenty of other (good) alternatives:

The Foreign Service Institutes’ varied list of courses

The Omniglot Intro to languages

BBC languages’ intro to almost 40 different languages

About’s language specific posts that explain particular aspects of languages well

You really do have plenty of options when it comes to free resources, so I suggest you try out several and see which ones work well for you. The aforementioned italki is great for language exchanges and lessons, but My Language Exchange and Interpals are two other options. You can take it offline and see about language related meet-ups in your city through The Polyglot Club, or the meet-ups pages on Couchsurfing, meetup.com, and Internations. These meet-ups are also great opportunities to meet an international crowd of fellow language learning enthusiasts, as well as native speakers of your target language, for practice.

But wait, there’s more. You can get further completely free language help on:

The huge database on Forvo, to hear any word or small expression in many languages read aloud by a native of the language

Rhinospike to make requests of specific phrases you’d like to hear pronounced by a native speaker. If you can’t find something on either of these sites, Google Translate has a text-to-speech option for many languages.

Lang 8 to receive free written corrections.

The possibilities for free practice are endless.

#6 – Realize that adults are actually better language learners than kids.

Now that you’re armed with a ton of resources to get started, let’s tackle the biggest problem. Not grammar, not vocabulary, not a lack of resources, but handicapping misconceptions about your own learning potential.

The most common “I give up” misconception is: I’m too old to become fluent.

I’m glad to be the bearer of good news and tell you that research has confirmed that adults can be better language learners than kids. This study at the University of Haifa has found that under the right circumstances, adults show an intuition for unexplained grammar rules better than their younger counterparts. [Note from Tim: This is corroborated by the book In Other Words and work by Hakuta.]

Also, no study has ever shown any direct correlation between reduced language acquisition skill and increased age. There is only a general downward trend in language acquisition in adults, which is probably more dependent on environmental factors that can be changed (e.g. long job hours that crowd out study time). Something my friend Khatzumoto (alljapaneseallthetime.com) once said that I liked was, “Babies aren’t better language learners than you; they just have no escape routes.”

As adults, the good news is that we can emulate the immersion environment without having to travel, spend a lot of money, or revert back to childhood.

#7 – Expand your vocabulary with mnemonics.

Rote repetition isn’t enough.

And while it’s true that repeated exposure sometimes burns a word into your memory, it can be frustrating to forget a word that you’ve already heard a dozen times.

For this, I suggest coming up with mnemonics about your target word, which helps glue the word to your memory way more effectively. Basically, you tell yourself a funny, silly, or otherwise memorable story to associate with a particular word. You can come up with the mnemonic yourself, but a wonderful (and free) resource that I highly recommend is memrise.com.

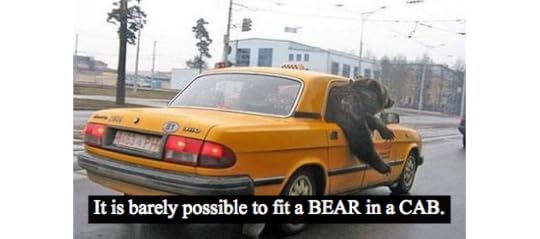

For instance, let’s say you are learning Spanish and can’t seem to remember that “caber” means “to fit,” no matter how many times you see it. Why not come up with a clever association like the following one I found on Memrise:

This [caber -> cab, bear -> fitting a bear in a cab] association makes remembering the word a cinch.

It may sound like a lengthy process, but try it a few times, and you’ll quickly realize why it’s so effective. And you’ll only need to recall this hook a couple of times, and then you can ditch it when the word becomes a natural part of your ability to use the language quickly.

#8 – Embrace mistakes.

Over half of the planet speaks more than one language.

This means that monolingualism is a cultural, not a biological, consequence. So when adults (at least in the English speaking world) fail at language learning, it’s not because they don’t have the right genes or other such nonsense. It’s because the system they have used to learn languages is broken.

Traditional teaching methods treat language learning just like any other academic subject, based on an approach that has barely changed since the days when Charles Dickens was learning Latin. The differences between your native language (L1) and your target language (L2) are presented as vocabulary and grammar rules to memorize. The traditional idea: know them “all” and you know the language. It seems logical enough, right?

The problem is that you can’t ever truly “learn” a language, you get used to it. It’s not a thing that you know or don’t know; it’s a means of communication between human beings. Languages should not be acquired by rote alone—they need to be used.

The way you do this as a beginner is to use everything you do know with emphasis on communication rather than on perfection. This is the pivotal difference. Sure, you could wait until you are ready to say “Excuse me kind sir, could you direct me to the nearest bathroom?” but “Bathroom where?” actually conveys the same essential information, only removing superfluous pleasantries. You will be forgiven for this directness, because it’s always obvious that you are a learner.

Don’t worry about upsetting native speakers for being so “bold” as to speak to them in their own language.

One of the best things you can do in the initial stages is not to try to get everything perfect, but to embrace making mistakes. I go out of my way to make at least 200 mistakes a day! This way I know I am truly using and practicing the language.

[TIM: I actually view part of my role as that of comedian or court jester--to make native speakers chuckle at my Tarzan speak. If you make people smile, it will make you popular, which will make you enthusiastic to continue.]

#9 – Create SMART goals.

Another failing of most learning approaches is a poorly defined end-goal.

We tend to have New Year’s Resolutions along the lines of “Learn Spanish,” but how do you know when you’ve succeeded? If this is your goal, how can you know when you’ve reached it?

Vague end goals like this are endless pits (e.g. “I’m not ready yet, because I haven’t learned the entire language”).

S.M.A.R.T. goals on the other hand are Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-bound.

To start developing your SMART goal in a language, I highly recommend you become somewhat familiar with the European Common Framework that defines language levels. This framework provides you with a way of setting specific language goals and measuring your own progress.

In brief, A means beginner, B means intermediate, and C means advanced, and each level is broken up into lower (1) and upper (2) categories. So an upper beginner speaker is A2, and a lower advanced speaker is C1. As well as being Specific, these levels are absolutely Measurable because officially recognized institutions can test you on them and provide diplomas (no course enrollment necessary) in German, French, Spanish, Irish, and each other official European language. While the same scale is not used, you can also get tested in a similar way in Chinese and Japanese.

So what do you aim for? And what do words like “fluency” and “mastery” mean on a practical level?

I’ve talked to many people to try to pinpoint the never-agreed-upon understanding of “fluency,” and I’ve found that it tends to average out around the B2 level (upper intermediate). This effectively means that you have “social equivalency” with your native language, which means that you can live in your target language in social situations in much the same way that you would in your native language, such as casual chats with friends in a bar, asking what people did over the weekend, sharing your aspirations and relating to people.

Since we are being specific, it’s also important to point out that this does not require that you can work professionally in a language (in my case, as an engineer or public speaker, for instance). That would be mastery level (generally C2).

Though I’ve reached the C2 stage myself in French, Spanish and am close to it in other languages, realistically I only really need to be socially equivalent in a language I want to communicate in. I don’t need to work in other languages. It’s essential that you keep your priorities clear to avoid frustration. Most of the time, just target B2.

To make your specific goal Attainable, you can break it down further. For example, I’ve found that the fluency (B2) level can be achieved in a matter of months, as long as you are focused on the spoken aspect.

In phonetic languages (like most European ones), you can actually learn to read along with speaking, so you get this effectively for free. But realistically, we tend to write emails and text messages—not essays—on a day-to-day basis (unless you are a writer by trade, and you may not have those goals with your L2). Focusing on speaking and listening (and maybe reading) makes fluency in a few months much more realistic.

Finally, to make your project Time-bound, I highly recommend a short end-point of a few months.

Keeping it a year or more away is far too distant, and your plans may as well be unbound at that point. Three months has worked great for me, but 6 weeks or 4 months could be your ideal point. Pick a definite point in the not too distant future (summer vacation, your birthday, when a family member will visit), aim to reach your target by this time, and work your ass off to make it happen.

To help you be smarter with your goals, make sure to track your progress and use an app like Lift to track completing daily essential tasks.

You can join the Lift plan for language learning that I wrote for their users here.

#10 – Jump from Conversational (B1) to Mastery (C2).

The way I reach spoken fluency quickly is to get a hell of a lot of spoken practice.

From day one to day 90 (and beyond), I speak at least an hour a day in my L2, and my study time is tailored around the spoken sessions to make sure that my conversation is what’s improving—not just my “general language skills” through some vague list of words I may never use.

So, for instance, I may start a session by asking what my native friend or teacher did over the weekend, and tell them what I did. Then I will share something that is on my mind lately and attempt to express my opinion on it, or allow the native speaker to introduce a new topic. It’s important to take an active role and make sure you are having varied conversations. Have a list of topics you would like to discuss and bring them up (your hobbies, hopes for the future, dislikes, what you will do on your vacation etc.) and make sure the conversation is constantly progressing.

Lots of practice and study to improve those spoken sessions tends to get me to lower intermediate (B1) level, which means I can understand the other person speaking to me fine as long as they are willing to speak clearly and adjust to my level and mistakes. It’s a LOT of work, mind you! On typical learning days I can be filled with frustration or feel like my brain is melting when–in fact–I’m truly making a lot of progress.

But the work is totally worth it when you have your first successful conversation with a native speaker. You’ll be thrilled beyond belief.

To see what this B1 level looks like, check out these videos of me chatting to a native in Arabic (in person with my italki teacher!), and in Mandarin with my friend Yangyang about how she got into working as a TV show host:

)

)

At this level, I still make plenty of mistakes of course, but they don’t hinder communication too much.

But to get over that plateau of just “good enough,” this is the point where I tend to return to academic material and grammar books, to tidy up what I have. I find I understand the grammar much better once I’m already speaking the language. This approach really works for me, but there is no one best language-learning approach. For instance, Tim has had great success by grammatically deconstructing a language right from the start. Your approach will depend entirely on your personality.

After lots of exercises to tidy up my mistakes at the B1 level, I find that I can break into B2.

At the B2 stage you can really have fun in the language! You can socialize and have any typical conversation that you’d like.

To get into the mastery C1/C2 levels though, the requirements are very different. You’ll have to start reading newspapers, technical blog posts, or other articles that won’t exactly be “light reading.”

To get this high-level practice, I’ve subscribed to newspapers on my Kindle that I try to read every day from various major news outlets around the world. Here are the top newspapers in Europe, South America and Asia. After reading up on various topics, I like to get an experienced professional (and ideally pedantic) teacher to grill me on the topic, to force me out of my comfort zone, and make sure I’m using precisely the right words, rather than simply making myself understood.

To show you what a higher level looks like, here is a chat I had with my Quebec Couchsurfer about the fascinating cultural and linguistic differences between Quebec and France (I would have been at a C1 level at this stage):

)

Reaching the C2 level can be extremely difficult.

For instance, I sat a C2 exam in German, and managed to hold my ground for the oral component, when I had to talk about deforestation for ten minutes, but I failed the exam on the listening component, showing me that I needed to be focused and pay attention to complicated radio interviews or podcasts at that level if I wanted to pass the exam in future.

#11 – Learn to sound more native.

At C2, you are as good as a native speaker in how you can work and interact in the language, but you may still have an accent and make the odd mistake.

I have been mistaken for a native speaker of my L2 several times (in Spanish, French and Portuguese – including when I was still at the B2/fluent level), and I can say that it’s a lot less related to your language level, and more related to two other factors.

First, your accent/intonation

Accent is obvious; if you can’t roll your R in Spanish you will be recognized as a foreigner instantly.

Your tongue muscles are not set in their ways forever, and you can learn the very few new sounds that your L2 requires that you learn. Time with a native, a good Youtube video explaining the sounds, and practice for a few hours may be all that you need!

What is much more important, but often overlooked, is intonation—the pitch, rise, fall, and stress of your words. When I was writing my book, I interviewed fellow polyglot Luca who is very effective in adapting a convincing accent in his target languages. For this, intonation is pivotal.

Luca trains himself from the very start to mimic the musicality and rhythm of a language’s natives by visualizing the sentences. For instance, if you really listen to it, the word “France” sounds different in “I want to go to France” (downward intonation) and “France is a beautiful country (intonation raising upwards). When you repeat sentences in your L2, you have to mimic the musicality of them.

My own French teacher pointed out a mistake I was making along these same lines.

I was trying to raise my intonation before pauses, which is a feature of French that occurs much more frequently than in English, but I was overdoing it and applying it to the ends of sentences as well. This made my sentences sound incomplete, and when my teacher trained me to stop doing this, I was told that I sounded way more French.

You can make these changes by focusing on the sounds of a language rather than just on the words.

Truly listen to and and mimic audio from natives, have them correct your biggest mistakes and drill the mistakes out of you. I had an accent trainer show me how this worked, and I found out some fascinating differences between my own Irish accent and American accents in the process! To see for yourself how the process works, check out the second half of this post with Soundcloud samples.

Second, walk like an Egyptian

The second factor that influences whether or not you could be confused for a native speaker, involves working on your social and cultural integration. This is often overlooked, but has made a world of difference to me, even in my early stages of speaking several languages.

For instance, when I first arrived in Egypt with lower intermediate Egyptian Arabic, I was disheartened that most people would speak English to me (in Cairo) before I even had a chance for my Arabic to shine. It’s easy to say that I’m too white to ever be confused for an Egyptian, but there’s more to it than that.

They took one look at me, saw how foreign I obviously was, and this overshadowed what language I was actually speaking to them.

To get around this problem, I sat down at a busy pedestrian intersection with a pen and paper and made a note of everything that made Egyptian men about my age different from me. How they walked, how they used their hands, the clothing they wore, their facial expressions, the volume they’d speak at, how they’d groom themselves, and much more. I found that I needed to let some stubble grow out, ditch my bright light clothes for darker and heavy ones (despite the temperature), exchange my trainers for dull black shoes, ditch my hat (I never saw anyone with hats), walk much more confidently, and change my facial expressions.

The transformation was incredible! Every single person for the rest of my time in Egypt would start speaking to me in Arabic, including in touristy parts of town where they spoke excellent English and would be well used to spotting tourists. This transformation allowed me to walk from the Nile to the Pyramids without any hassle from touts and make the experience all about the fascinating people I met.

Try it yourself, and you’ll see what I mean—once you start paying attention, the physical social differences will become easy to spot.

You can observe people directly, or watch videos of natives you’d like to emulate from a target country. Really try to analyze everything that someone of your age and gender is doing, and see if you can mimic it next time you are speaking.

Imitation is, after all, the most sincere form of flattery!

#12 – Become a polyglot.

This post has been an extremely detailed look at starting off and trying to reach mastery in a foreign language (and even passing yourself off as a native of that country).

If your ultimate goal is to speak multiple languages, you can repeat this process over multiple times, but I highly recommend you focus on one language at a time until you reach at least the intermediate level. Take each language one by one, until you reach a stage where you know you can confidently use it. And then you may just be ready for the next ones!

While you can do a lot in a few months, if you want to speak a language for the rest of your life it requires constant practice, improvement, and living your life through it as often as you can. But the good news is — once you reach fluency in a language, it tends to stick with you pretty well.

Also, keep in mind that while the tips in this article are an excellent place to start, there is a huge community of “polyglots” online willing to offer you their own encouragement as well. A bunch of us came together in this remix, “Skype me Maybe.”

)

I share several more stories about these polyglots and dive into much greater detail about how to learn languages in my newly released book Fluent in 3 Months. Grab a copy, or check out my site for inspiration to start your adventure in becoming fluent in a new language—or several.

Ganbatte!

###

Question of the Day: What tools or approaches have you used for learning languages? Please share in the comments!

March 20, 2014

The Art of Learning: The Tool of Choice for Top Athletes, Traders, and Creatives

This post is about the third book in the Tim Ferriss Book Club, which is limited to books that have dramatically impacted my life. Enjoy!

“I strongly recommend [The Art of Learning] for anyone who lives in a world of competition, whether it’s sports or business or anywhere else.”

- Mark Messier, 6-Time Stanley Cup Champion

“[This book] is a testimonial to the timeless principle of ‘do less and accomplish more.’ Highly recommended.”

- Deepak Chopra

“Josh provides tools that allow all of us to improve ourselves every day.”

- Cal Ripken, Jr., Baseball Hall of Fame Inductee

How do the best performers in the world become the best in the world?

The newest book in the Tim Ferriss Book Club provides the answers and blueprint: The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance by Joshua Waitzkin, the subject of Searching for Bobby Fischer. It’s been one of my constant companions since 2007, and I’m THRILLED to shine the spotlight on it.

Want to dominate sports? See the quotes from Cal Ripken, Jr. and Mark Messier above. There are many more.

Want to dominate business or finance? Many of the Forbes 100 work one-on-one with Josh. I personally know hedgefund managers, with $10-100 billion under management, who have The Art of Learning on their bedside tables.

Want to maximize creativity? Robert Pirsig, author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, says “This is a really superb book, one I wish someone had given to me long ago… It will take a ferocious interruption to make you set this book down.”

Want to up your game, no matter the game? This book is your guide.

The Audible version of the audiobook can be found here.

This post includes several things, including:

A brief personal story about Josh

A sample chapter, both in audio and text

A video overview

But perhaps you’re in a rush. Want the book synopsis in one sentence? Here it is: Through stories of martial arts wars and tense chess face-offs, Waitzkin reveals the inner workings of his everyday methods, including systematically triggering breakthroughs, cultivating top-1% technique in any field, and mastering the art of performance psychology.

The Art of Learning encapsulates an extraordinary competitor’s life lessons into a page-turning narrative.

Download or stream the book here!

My Story with Josh — Love at First F-Bomb

I first met Josh Waitzkin at a coffee shop in Manhattan.

Having just read The Art of Learning, I was as giddy as a schoolgirl that he’d agreed to come. I don’t have many heroes, and he was one of them.

About 15 minutes into sipping coffee and getting acquainted, I realized that he dropped as many f-bombs as I did. He was no Rain Man, and I felt silly for half expecting him to be. 15 minutes turned into nearly three hours, and he’s since become one of my best friends.

If you’ve read the bestselling book Searching for Bobby Fischer (or seen the movie), then you know of Josh.

Wandering through Washington Square Park with his mom at age six, he became fascinated with the “blitz chess” that the street hustlers played at warp speed. He watched and absorbed. Then he begged his mom to let him give it a shot. Just once! Soon thereafter, dressed in OshKosh overalls, he was king of the hustlers.

Josh proceeded to dominate the world chess scene and become the only person to win the National Primary, Elementary, Junior High School, Senior High School, U.S. Cadet, and U.S. Junior Closed chess championships before the age of 16. He could easily play “simuls,” in which 20-50 chessboards were set up with opponents in a large banquet hall, requiring him to walk from table to table playing all of the games simultaneously in his head.

He was labeled a “prodigy” (more on this shortly).

But how did he really become so good?

Partially by breaking the rules. Bruce Pandolfini, Josh’s original chess teacher, started their first class by taking him in reverse. The board was empty, except for three pieces in an endgame scenario: king and pawn against king. Memorizing openings was forbidden at the start.

Learning chess in reverse?

Yes, and this is just one of the many accelerated learning techniques Josh has refined and perfected over the last 20 years.

Calling Josh a “chess prodigy” is a misnomer because Josh defies pigeonholing. He has a PROCESS for mastering skills — one you can use yourself — and he’s applied it to many fields, not just chess.

He tackled Tai Chi Chuan after leaving the chess world behind. 13 Push Hands National Championships and two World Championship titles later, he decided to train in Brazilian jiu-jitsu. Now, a few short years later, he’s a black belt under the Michael Jordan of BJJ, Marcelo Garcia.

As Josh has put it: “I’ve come to realize that what I am best at is not Tai Chi, and it is not chess. What I am best at is the art of learning.”

If you want to get the most out of life, you need to get his book.

You won’t regret it.

I’ll also be creating a message board so we can discuss this book and others.

Download or stream the book here!

Sample Chapter — The Introduction

[Below is just one of 20 chapters in The Art of Learning. Audio is embedded first, followed by text for the same chapter.]

Finals: Tai Chi Chuan Push Hands World Championships

Hsinchuang Stadium, Taipei, Taiwan December 5, 2004

Forty seconds before round two, and I’m lying on my back trying to breathe.

Pain all through me. Deep breath. Let it go. I won’t be able to lift my shoulder tomorrow, it won’t heal for over a year, but now it pulses, alive, and I feel the air vibrating around me, the stadium shaking with chants, in Mandarin, not for me.

My teammates are kneeling above me, looking worried. They rub my arms, my shoulders, my legs. The bell rings. I hear my dad’s voice in the stands, ‘C’mon Josh!’ Gotta get up. I watch my opponent run to the center of the ring. He screams, pounds his chest. The fans explode. They call him Buffalo. Bigger than me, stronger, quick as a cat. But I can take him — if I make it to the middle of the ring without falling over. I have to dig deep, bring it up from somewhere right now. Our wrists touch, the bell rings, and he hits me like a Mack truck.

Who could have guessed it would come to this? Just a few years earlier I had been competing around the world in elite chess tournaments. Since I was eight years old, I had consistently been the highest rated player for my age in the United States, and my life was dominated by competitions and training regimens designed to bring me into peak form for the next national or world championship. I had spent the years between ages fifteen and eighteen in the maelstrom of American media following the release of the film Searching for Bobby Fischer, which was based on my dad’s book about my early chess life. I was known as America’s great young chess player and was told that it was my destiny to follow in the footsteps of immortals like Bobby Fischer and Garry Kasparov, to be world champion.

But there were problems. After the movie came out I couldn’t go to a tournament without being surrounded by fans asking for autographs. Instead of focusing on chess positions, I was pulled into the image of myself as a celebrity. Since childhood I had treasured the sublime study of chess, the swim through ever-deepening layers of complexity. I could spend hours at a chessboard and stand up from the experience on fire with insight about chess, basketball, the ocean, psychology, love, art. The game was exhilarating and also spiritually calming. It centered me. Chess was my friend. Then, suddenly, the game became alien and disquieting.

I recall one tournament in Las Vegas: I was a young International Master in a field of a thousand competitors including twenty-six strong Grandmasters from around the world. As an up-and-coming player, I had huge respect for the great sages around me. I had studied their masterpieces for hundreds of hours and was awed by the artistry of these men. Before first-round play began I was seated at my board, deep in thought about my opening preparation, when the public address system announced that the subject of Searching for Bobby Fischer was at the event. A tournament director placed a poster of the movie next to my table, and immediately a sea of fans surged around the ropes separating the top boards from the audience. As the games progressed, when I rose to clear my mind young girls gave me their phone numbers and asked me to autograph their stomachs or legs.

This might sound like a dream for a seventeen-year-old boy, and I won’t deny enjoying the attention, but professionally it was a nightmare. My game began to unravel. I caught myself thinking about how I looked thinking instead of losing myself in thought. The Grandmasters, my elders, were ignored and scowled at me. Some of them treated me like a pariah. I had won eight national championships and had more fans, public support and recognition than I could dream of, but none of this was helping my search for excellence, let alone for happiness.

At a young age I came to know that there is something profoundly hollow about the nature of fame. I had spent my life devoted to artistic growth and was used to the sweaty-palmed sense of contentment one gets after many hours of intense reflection. This peaceful feeling had nothing to do with external adulation, and I yearned for a return to that innocent, fertile time. I missed just being a student of the game, but there was no escaping the spotlight. I found myself dreading chess, miserable before leaving for tournaments. I played without inspiration and was invited to appear on television shows. I smiled.

Then when I was eighteen years old I stumbled upon a little book called the Tao Te Ching, and my life took a turn. I was moved by the book’s natural wisdom and I started delving into other Buddhist and Taoist philosophical texts. I recognized that being at the pinnacle in other people’s eyes had nothing to do with quality of life, and I was drawn to the potential for inner tranquility.

On October 5, 1998, I walked into William C. C. Chen’s Tai Chi Chuan studio in downtown Manhattan and found myself surrounded by peacefully concentrating men and women floating through a choreographed set of movements. I was used to driven chess players cultivating tunnel vision in order to win the big game, but now the focus was on bodily awareness, as if there were some inner bliss that resulted from mindfully moving slowly in strange ways.

I began taking classes and after a few weeks I found myself practicing the meditative movements for hours at home. Given the complicated nature of my chess life, it was beautifully liberating to be learning in an environment in which I was simply one of the beginners — and something felt right about this art. I was amazed by the way my body pulsed with life when flowing through the ancient steps, as if I were tapping into a primal alignment.

My teacher, the world-renowned Grandmaster William C.C. Chen, spent months with me in beginner classes, patiently correcting my movements. In a room with fifteen new students, Chen would look into my eyes from twenty feet away, quietly assume my posture, and relax his elbow a half inch one way or another. I would follow his subtle instruction and suddenly my hand would come alive with throbbing energy as if he had plugged me into a soothing electrical current. His insight into body mechanics seemed magical, but perhaps equally impressive was Chen’s humility. Here was a man thought by many to be the greatest living Tai Chi Master in the world, and he patiently taught first-day novices with the same loving attention he gave his senior students.

I learned quickly, and became fascinated with the growth that I was experiencing. Since I was twelve years old I had kept journals of my chess study, making psychological observations along the way — now I was doing the same with Tai Chi.

After about six months of refining my form (the choreographed movements that are the heart of Tai Chi Chuan), Master Chen invited me to join the Push Hands class. This was very exciting, my baby steps toward the martial side of the art. In my first session, my teacher and I stood facing each other, each of us with our right leg forward and the backs of our right wrists touching. He told me to push into him, but when I did he wasn’t there anymore. I felt sucked forward, as if by a vacuum. I stumbled and scratched my head. Next, he gently pushed into me and I tried to get out of the way but didn’t know where to go. Finally I fell back on old instincts, tried to resist the incoming force, and with barely any contact Chen sent me flying into the air.

Over time, Master Chen taught me the body mechanics of nonresistance. As my training became more vigorous, I learned to dissolve away from attacks while staying rooted to the ground. I found myself calculating less and feeling more, and as I internalized the physical techniques all the little movements of the Tai Chi meditative form started to come alive to me in Push Hands practice. I remember one time, in the middle of a sparring session I sensed a hole in my partner’s structure and suddenly he seemed to leap away from me. He looked shocked and told me that he had been pushed away, but he hadn’t noticed any explosive movement on my part. I had no idea what to make of this, but slowly I began to realize the martial power of my living room meditation sessions. After thousands of slow-motion, ever-refined repetitions of certain movements, my body could become that shape instinctively. Somehow in Tai Chi the mind needed little physical action to have great physical effect.

This type of learning experience was familiar to me from chess. My whole life I had studied techniques, principles, and theory until they were integrated into the unconscious. From the outside Tai Chi and chess couldn’t be more different, but they began to converge in my mind. I started to translate my chess ideas into Tai Chi language, as if the two arts were linked by an essential connecting ground. Every day I noticed more and more similarities, until I began to feel as if I were studying chess when I was studying Tai Chi. Once I was giving a forty-board simultaneous chess exhibition in Memphis and I realized halfway through that I had been playing all the games as Tai Chi. I wasn’t calculating with chess notation or thinking about opening variations…I was feeling flow, filling space left behind, riding waves like I do at sea or in martial arts. This was wild! I was winning chess games without playing chess.

Similarly, I would be in a Push Hands competition and time would seem to slow down enough to allow me to methodically take apart my opponent’s structure and uncover his vulnerability, as in a chess game. My fascination with consciousness, study of chess and Tai Chi, love for literature and the ocean, for meditation and philosophy, all coalesced around the theme of tapping into the mind’s potential via complete immersion into one and all activities. My growth became defined by barrierlessness. Pure concentration didn’t allow thoughts or false constructions to impede my awareness, and I observed clear connections between different life experiences through the common mode of consciousness by which they were perceived.

As I cultivated openness to these connections, my life became flooded with intense learning experiences. I remember sitting on a Bermuda cliff one stormy afternoon, watching waves pound into the rocks. I was focused on the water trickling back out to sea and suddenly knew the answer to a chess problem I had been wrestling with for weeks. Another time, after completely immersing myself in the analysis of a chess position for eight hours, I had a breakthrough in my Tai Chi and successfully tested it in class that night. Great literature inspired chess growth, shooting jump shots on a New York City blacktop gave me insight about fluidity that applied to Tai Chi, becoming at peace holding my breath seventy feet underwater as a free-diver helped me in the time pressure of world championship chess or martial arts competitions. Training in the ability to quickly lower my heart rate after intense physical strain helped me recover between periods of exhausting concentration in chess tournaments. After several years of cloudiness, I was flying free, devouring information, completely in love with learning.

***

Before I began to conceive of this book, I was content to understand my growth in the martial arts in a very abstract manner. I related to my experience with language like parallel learning and translation of level. I felt as though I had transferred the essence of my chess understanding into my Tai Chi practice. But this didn’t make much sense, especially outside of my own head. What does essence really mean anyway? And how does one transfer it from a mental to a physical discipline?

These questions became the central preoccupation in my life after I won my first Push Hands National Championship in November 2000. At the time I was studying philosophy at Columbia University and was especially drawn to Asian thought. I discovered some interesting foundations for my experience in ancient Indian, Chinese, Tibetan, and Greek texts — Upanishadic essence, Taoist receptivity, Neo-Confucian principle, Buddhist nonduality, and the Platonic forms all seemed to be a bizarre cross-cultural trace of what I was searching for. Whenever I had an idea, I would test it against some brilliant professor who usually disagreed with my conclusions. Academic minds tend to be impatient with abstract language — when I spoke about intuition, one philosophy professor rolled her eyes and told me the term had no meaning. The need for precision forced me to think about these ideas more concretely. I had to come to a deeper sense of concepts like essence, quality, principle, intuition, and wisdom in order to understand my own experience, let alone have any chance of communicating it.

As I struggled for a more precise grasp of my own learning process, I was forced to retrace my steps and remember what had been internalized and forgotten. In both my chess and martial arts lives, there is a method of study that has been critical to my growth. I sometimes refer to it as the study of numbers to leave numbers, or form to leave form. A basic example of this process, which applies to any discipline, can easily be illustrated through chess: A chess student must initially become immersed in the fundamentals in order to have any potential to reach a high level of skill. He or she will learn the principles of endgame, middlegame, and opening play. Initially one or two critical themes will be considered at once, but over time the intuition learns to integrate more and more principles into a sense of flow. Eventually the foundation is so deeply internalized that it is no longer consciously considered, but is lived. This process continuously cycles along as deeper layers of the art are soaked in.

Very strong chess players will rarely speak of the fundamentals, but these beacons are the building blocks of their mastery. Similarly, a great pianist or violinist does not think about individual notes, but hits them all perfectly in a virtuoso performance. In fact, thinking about a “C” while playing Beethoven’s 5th Symphony could be a real hitch because the flow might be lost. The problem is that if you want to write an instructional chess book for beginners, you have to dig up all the stuff that is buried in your unconscious — I had this issue when I wrote my first book, Attacking Chess. In order to write for beginners, I had to break down my chess knowledge incrementally, whereas for years I had been cultivating a seamless integration of the critical information.

The same pattern can be seen when the art of learning is analyzed: themes can be internalized, lived by, and forgotten. I figured out how to learn efficiently in the brutally competitive world of chess, where a moment without growth spells a front-row seat to rivals mercilessly passing you by. Then I intuitively applied my hard-earned lessons to the martial arts. I avoided the pitfalls and tempting divergences that a learner is confronted with, but I didn’t really think about them because the road map was deep inside me — just like the chess principles.

Since I decided to write this book, I have analyzed myself, taken my knowledge apart, and rigorously investigated my own experience. Speaking to corporate and academic audiences about my learning experience has also challenged me to make my ideas more accessible. Whenever there was a concept or learning technique that I related to in a manner too abstract to convey, I forced myself to break it down into the incremental steps with which I got there. Over time I began to see the principles that have been silently guiding me, and a systematic methodology of learning emerged.

My chess life began in Washington Square Park in New York’s Greenwich Village, and took me on a sixteen-year-roller-coaster ride, through world championships in America, Romania, Germany, Hungary, Brazil, and India, through every kind of heartache and ecstasy a competitor can imagine. In recent years, my Tai Chi life has become a dance of meditation and intense martial competition, of pure growth and the observation, testing, and exploration of that learning process. I have currently won thirteen Tai Chi Chuan Push Hands National Championship titles, placed third in the 2002 World Championship in Taiwan, and in 2004 I won the Chung Hwa Cup International in Taiwan, the World Championship of Tai Chi Chuan Push Hands.

A lifetime of competition has not cooled my ardor to win, but I have grown to love the study and training above all else. After so many years of big games, performing under pressure has become a way of life. Presence under fire hardly feels different from the presence I feel sitting at my computer, typing these sentences. What I have realized is that what I am best at is not Tai Chi, and it is not chess — what I am best at is the art of learning.

This book is the story of my method.

Video Overview

Below is a short video overview of The Art of Learning. Don’t miss the hilarious outtakes starting around 4:45:

###

Download or stream the entire book here!

Alternatively, the Audible version of the audiobook can be found here, but the author earns lower royalties than purchases through the link above.

QOD: If you’ve met or studied any world-class performers, what did you learn from them? What lessons have you learned from observing the greats? Please share in the comments!

March 12, 2014

12 Rules for Learning Foreign Languages in Record Time — The Only Post You’ll Ever Need

Preface by Tim Ferriss

I’ve written about how I learned to speak, read, and write Japanese, Mandarin, and Spanish. I’ve also covered my experiments with German, Indonesian, Arabic, Norwegian, Turkish, and perhaps a dozen others.

There are only few language learners who dazzle me, and Benny Lewis is one of them.

This definitive guest post by Benny will teach you:

How to speak your target language today.

How to reach fluency and exceed it within a few months.

How to pass yourself off as a native speaker.

And finally, how to tackle multiple languages to become a “polyglot”—all within a few years, perhaps as little as 1-2.

It contains TONS of amazing resources I never even knew existed, including the best free apps and websites for becoming fluent in record time. Want to find a native speaker to help you for $5 per hour? Free resources and memory tricks? It’s all here.

This is a post you all requested, so I hope you enjoy it!

Enter Benny

You are either born with the language-learning gene, or you aren’t. Luck of the draw, right? At least, that’s what most people believe.