Corey Robin's Blog, page 29

October 23, 2017

Forty Years of The Firm: Trump and the Coasian Grotesque

In his classic article “The Nature of the Firm“—which I wish would be put on the list of required reading for political theorists; it really should be in our canon—the economist R.H. Coase divides the economic world into two modes of action: deal-making, which happens between firms, and giving orders, which happens within firms. Coase doesn’t say this, but it’s a plausible extrapolation that making deals and giving orders are, basically, the two things businessmen know how to do.

In the last year, it’s occurred to me, on more than one occasion, that Trump is a Coasian grotesque. Making deals and giving orders: that’s all he knows how to do. Except that he doesn’t. As we’re seeing, he’s really bad at both.

Regardless of whether he’s good or bad at the ways and means of the firm, what Trump definitely doesn’t know is politics. Authority, legitimacy, persuasion, leadership: these are arts that Trump is completely unpracticed at, and it shows. When it comes to wielding power in the political sphere—I’m not talking about executive orders, of which Trump has issued many, and which are a sign of his weakness, not his strength; I’m talking about exercising power that requires the assent and cooperation of other political actors—he’s completely out of his league.

There’s a reason for that: the conception of he power has—such as it is and however bad he is at it—is drawn from the Coasian world of the firm. To that extent, we can read Trump’s failure not simply as a referendum on Trump, not simply as a referendum on the Republican Party, but more largely and more importantly, as a verdict on 40 years of politics in the United States. For what neoliberalism has meant, among other things, is not simply the rise of markets and money and all the rest; it has also meant, as Wendy Brown has argued so compellingly, the rise of economic modes of reason and their insertion into politics. Not just their insertion, but their domination. Such that our entire conception of political leadership is drawn from the world of the firm (that’s not Brown’s argument; it’s my tangent to her argument).

This is not a story of the rise of Reagan or the Republican Party. It’s a completely bipartisan story. It was Jimmy Carter, in 1975, who helped begin the story, when he launched his presidential campaign with the claim: “I ran the Georgia government as well as almost any corporate structure in this country is run.” Four decades later, managing a firm no longer provides a standard of leadership. It is the substance of leadership.

A substance, as we are now seeing, that is increasingly irrelevant to the challenges of our age. Trump’s problem is not that he’s bad at making deals or giving commands. Even if he were good at that, it’d not be sufficient to manage the crises of his coalition. A different sort of art is called for, one that is not drawn from the firm.

If we had a real political opposition, if we had a real left, they’d be using Trump not as an example of right-wing lunacy or Republican perfidy; he’d be Exhibit A of Forty Years of the Firm.

October 21, 2017

Noah and Shoah: Purification by Violence from the Flood to the Final Solution

In shul this morning, I was musing on this passage from Genesis 8:21, which was in the parsha, or Torah portion, we read for the week:

…the Lord said to Himself: “Never again will I doom the earth because of man, since the devisings of man’s mind are evil from his youth; nor will I ever again destroy every living being, as I have done.”

This statement comes just after the Flood has ended. God commands Noah to leave the ark, to take all the animals with him. Noah does that and then makes an offering to God. God is pleased by the offering, and suddenly—out of nowhere—makes this resolution: I won’t do this again. I won’t drown the world, destroy its ways (“So long as the earth endures, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, summer and winter, day and night, shall not cease”) or its beings, again.

This is no sudden moment of humanitarianism on God’s part. There’s not even a hint of regret or remorse in the passage. But it is an acknowledgment on God’s part, a resolution born of a sad realization, that the Flood was a mistake. Born of a very wrong-headed idea.

The original idea of the Flood was not to destroy all of creation, to rid God of God’s work. If that were the case, why tell Noah to build an ark for him and his family and the animals? No, the idea was to destroy all that part of creation that was evil and wicked and tainted—but to separate and save a remnant of goodness that would be the seed of a new civilization.

The destruction of the Flood, in other words, was violence of a particular and familiar kind: a purifying, separating violence of the sort we so often see in ethnic cleansing or genocide. Get rid of the stain, which can be located in a specific people or place, separate the remnant from that stain, and you can begin again, with goodness and virtue and purity.

What is God’s realization? It doesn’t work. Stains are everywhere, evil is everywhere, you can’t murder your way to goodness, you can’t purify through violence. Other ways must be found, other means are necessary. This isn’t an argument against political violence or even violence, which have their strategic uses. It’s an argument against the notion that violence can purify, that violence can make a people spiritually, morally, whole.

The ethnic cleansing/genocide comparison came to me while reading another passage in Genesis, not long before this one. It’s just before the Flood begins. Noah has built the ark, as God commanded. He’s gathered all manner of animal and his family. And then God commands them to go in. It’s not clear if they go up or down into the ark; if they ascend or descend. But in they go, silently as far as we know, two by two. The passage ends with this terrible sentence:

And the Lord shut them in.

I had never thought it before, but the passage reminded me of descriptions of Jews going into the gas chambers. There’s a particularly visual moment I had in mind from the movie Denial, about the Holocaust historian Deborah Lipstadt who is sued for libel by David Irving. In one scene, Lipstadt and her attorney travel to Auschwitz on a research mission, and as they’re looking around Auschwitz, they come upon a gas chamber, which is preceded by a long downward ramp. Something people would walk down and from which they would enter the chamber, where they would then be shut in.

For some reason, the passage I read, culminating in “the Lord shut them in,” called that scene to mind. Only in the Bible, the genocide works in reverse: those who are shut in the ark are saved; everyone else is destroyed.

If the comparison offends or horrifies you, I completely understand. I was jarred by it myself; it made me uncomfortable. And I don’t raise it to be provocative or to over-share a thought better kept to myself. Because the more I thought about it, the more the resonances between the Flood and the Final Solution, between Noah and Shoah, came.

So it’s clear, as I said, that God knows the Flood was a mistake, on a massive scale. And it’s a mistake, as I said, born of this terrible idea: that you can murder your way to purity, that you can remove the stain by separating out a part of a people and destroying the rest. This is why, immediately following that realization, God makes a covenant with Noah. Every time it rains, there will be a rainbow: a sign of God’s promise that God will never again destroy the earth by flood (or other measures, the passage seems to suggest). This is the famous “rainbow sign,” which figures in that couplet from a black spiritual—God gave Noah the rainbow sign. No more water, the fire next time—that gave the title to James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time.

(How we square that promise from God with the multiple mass murders and cleansings that follow in the Bible—from Sodom and Gommorah to the Israelites slaughtering the Canaanites—is another story.)

But after God makes this promise, we come to the Tower of Babel story. That story, I would argue, is an epilogue to the story of the Flood. It is about humanity’s own encounter with the very impulse that God has just indulged and then renounced.

The men and women who build the Tower of Babel are not unlike God in the Flood. Traditional interpretations see that imitation of God as the sin, the wrong, at the heart of the Tower of Babel story. The men and women who built the tower, the argument goes, were inspired by hubris, they wanted to be as high as God, and so on.

But read against the Flood, the Tower of Babel suggests a different interpretation: the sin was not wanting to be like God. The sin was to repeat the same mistake God had just made with the Flood: that is, wanting to purify your way to unity by separating yourselves from the rest of humanity.

Upon seeing the Tower, God notes:

Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language;

God serves here not as a judge but as a witness, as a narrator or stand-in for the reader. God observes here, for us, that the people’s oneness is the problem. (There’s a different interpretation of this passage, which focuses on how separation and division make collective action and solidarity impossible, but I want to set that aside for another day.) The people have built their way, have cloistered themselves, into oneness. It’s true that no violence is mentioned in the story, but our rabbi in shul today told us of an ancient midrash or commentary that says that in the building of the Tower, the men and women cared more about the bricks than the workers who built it. So the workers would fall from the height and no one would notice or care, but a brick would fall, and all would wail and weep. In their aspiration for wholeness and unity via separation, a holy unity that would mimic the moral purity and perfection of heaven precisely because it was so removed from the rest of the earth—”let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth”—the people of the Tower willingly countenanced all manner of murder and mayhem. Not unlike what God did in the Flood.

And how does God deal with that desire for purification by separation, that violence that they countenance on their way to unity?

Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech. So the LORD scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth:

God establishes plurality, the multiplicity of peoples, the varieties of culture and language, as a condition of the world. Not as a punishment for hubris, I would argue, not as a punishment for seeking improvement or even working toward utopia, but as a reminder and a reaffirmation of what God came to realize after the Flood: purification by violence, moral wholeness by separation, final solutions—none of these is an answer to the condition of the world. They are, in fact, an assault on the condition of the world.

This, as Hannah Arendt recognized in her famous epilogue to Eichmann in Jerusalem, was the Nazis’ great crime, the crime for which Eichmann should hang. “And just as you,” she imagines a court telling Eichmann,

supported and carried out a policy of not wanting to share the earth with the Jewish people and the people of a number of other nations—as though you and your superiors had any right to determine who should and who should not inhabit the world—we find that no one, that is, no member of the human race, can be expected to want to share the earth with you.

October 20, 2017

If you don’t think that some day you’ll be looking back fondly on Trump, think again: That day has already come.

Back in March 2016, I made a prediction:

If, God forbid, Trump is elected, some day, assuming we’re all still alive, we’ll be having a conversation in which we look back fondly, as we survey the even more desultory state of political play, on the impish character of Donald Trump. As Andrew March said to me on Facebook, we’ll say something like: What a jokester he was. Didn’t mean it at all. But, boy, could he cut a deal.

When I wrote that, I was thinking of all the ways in which George W. Bush, a man vilified by liberals for years, was being rehabilitated, particularly in the wake of Trump’s rise.

Yesterday’s speech, in which Bush obliquely took on Trump, was merely the latest in a years-long campaign to restore his reputation and welcome him back into the fold of respectability.

Remember when Michelle Obama gave him a hug?

That was Step 2 or 3. Yesterday’s speech was Step 4.

For years prior to that, our image of Bush was emblazoned by the memory of not only the Iraq War, which killed hundreds of thousands of people, of not only the casual violence, the fratboyish, near-sociopathic, irresponsibility, of Bush’s rhetoric of war (remember when, after the Iraq War was over, in June 2003, Bush turned to his Administrator General there, Jay Garner, and said, “Hey, Jay, you want to do Iran?”). It was also imprinted with the memory of the laziness and incuriosity, the buoyant indifference, that got us into war, not just the Iraq War but also the war on terror (the original sin of it all, if you ask me) in the first place.

All those now pining for the pre-9/11 George W. Bush, a man who took his responsibilities to the nation—and his duty to its people—seriously, an anti-Trump who, whatever his many flaws, at least had a sense of the gravitas of his office and its burdens, might want to have a read-through to what was going down in the Bush administration ca. August 2001.

Roemer then asked Tenet if he mentioned Moussaoui to President Bush at one of their frequent morning briefings. Tenet replied, “I was not in briefings at this time.” Bush, he noted, “was on vacation.” He added that he didn’t see the president at all in August 2001. During the entire month, Bush was at his ranch in Texas. “You never talked with him?” Roemer asked. “No,” Tenet replied.

…

And there you have it. National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice has made a big point of the fact that Tenet briefed the president nearly every day. Yet at the peak moment of threat, the two didn’t talk at all. At a time when action was needed, and orders for action had to come from the top, the man at the top was resting undisturbed.

Throughout that summer, we now well know, Tenet, Richard Clarke, and several other officials were running around with their “hair on fire,” warning that al-Qaida was about to unleash a monumental attack. On Aug. 6, Bush was given the now-famous President’s Daily Brief (by one of Tenet’s underlings), warning that this attack might take place “inside the United States.” For the previous few years—as Philip Zelikow, the commission’s staff director, revealed this morning—the CIA had issued several warnings that terrorists might fly commercial airplanes into buildings or cities.

And now, we learn today, at this peak moment, Tenet hears about Moussaoui. Someone might have added 2 + 2 + 2 and possibly busted up the conspiracy. But the president was down on the ranch, taking it easy. Tenet wasn’t with him. Tenet never talked with him. Rice—as she has testified—wasn’t with Bush, either. He was on his own and, willfully, out of touch.

But now that’s all forgotten. Or being forgotten.

It may be, however, when it comes to Trump’s rehabilitation, that things will move faster than I predicted, that Trump won’t have to wait as long as Bush to get out of the doghouse.

After all, Sean Spicer is now up at Harvard, tutoring the hopefuls of tomorrow’s ruling class.

Visiting Fellow @Seanspicer talks to students over breakfast about the state of politics in America. pic.twitter.com/bBOkBhRKeV

— InstituteOfPolitics (@HarvardIOP) October 18, 2017

And just after Roy Moore got the nomination in Alabama, Paul Begala was quoted in Politico:

What do they say in recoveries? You have to hit bottom? I thought that, with Trump, they [the GOP] hit bottom. But, apparently not, because Moore is worse.

And there you have it, the stage is already being set. Given the relentless march rightward of the Republican Party, there will always be something worse waiting in the wings, something worse that will inevitably furnish Trump with a retrospective glow—even though it was Trump who set the stage for that something worse, in the same way that it was Bush who set the stage for Trump.

So, here’s a message to everyone on Twitter or Facebook saying, gee, I never thought I’d be saying this, but next to Trump, George W. Bush really isn’t so bad: One day, I promise you, I guarantee you, you will be saying, gee, I never thought I’d be saying this, but next to TK [that’s editor-speak for “to come”], Trump really isn’t so bad.

Unless, that is, you get out of this terrible habit of burnishing the past—something you can only do because it’s no longer in front of you—and dehistoricizing the present.

October 18, 2017

Was Bigger Thomas an Uptalker?

The funniest moment in Native Son (not a novel known for its comedy, I know): when the detective, Mr. Britten, is asking the housekeeper, Peggy, a bunch of questions about Bigger Thomas, to see if Thomas is in fact a Communist.

Britten: When he talks, does he wave his hands around a lot, like he’s been around a lot of Jews?

Peggy: I never noticed, Mr. Britten.

…

Britten: Now, listen, Peggy. Think and try to remember if his voice goes up when he talks, like Jews, when they talk. Know what I mean? You see, Peggy, I’m trying to find out if he’s been around Communists.

Interesting side note: how much more terrified the white power structure in that novel is of the Reds than of black people; though the two fears are obviously mingled, the anticommunist phobia is much more overt.

Other interesting side note: Along with Invisible Man, Native Son is one of Clarence Thomas’s favorite novels.

October 15, 2017

“It’s Scalias All the Way Down”: Why the very thing that scholars think is the antidote to Trump is in fact the aide-de-Trump

Trump was upbeat and brought up a Kim Strassell column in The Wall Street Journal, “Scalias all the way down,” giving the president credit for “remaking the federal judiciary.”‘

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again. While political scientists warn against the norm erosion of the Trump presidency—and dwell on the importance of the courts, the Constitution, and the rule of law as antidotes—the most far-seeing leaders of the conservative movement and the Republican party understand that long after Trump has left the stage, long after the Republican Party has lost its hold over the political discourse and political apparatus, it will be Trump’s judiciary—interpreting the Constitution, applying the rule of law—that preserves and extends his legacy.

People often ask me why I criticize this language of norm erosion, why I go after social scientists ringing the warning bell against Trump. One of the reasons is that the very terms of their analysis not only ignore the real long-term threat of Trumpism but actually hold up that long-term threat—an independent judiciary interpreting the Constitution (for that is what, in 30 years, Trump’s judiciary will be)—as somehow the answer and antidote to our situation.

That analysis is completely backassward, and it really does us a disservice. Trump’s real threat is not that he will destroy institutions or the Constitution; it’s that institutions and the Constitution will preserve him, long after he’s gone.

As we approach the one-year anniversary of Donald Trump’s election…

As we approach the one-year anniversary of Trump’s election, I notice an uptick in two types of commentary.

First, there’s a focus on the barrenness of Trump’s legislative record. It really is astonishing, and something we can forget amid the day-to-day sense of crisis, but compared to every modern president, Trump’s achievements in the truly political domains of the presidency—that is, those domains that require the assent, cooperation, or agreement of other politicians and the majority of citizens—have been miniscule. I rarely agree with Nancy Pelosi these days, but with the exception of the Gorsuch nomination (which, truth be told, was McConnell’s achievement, not Trump’s), she’s right:

“We didn’t win the elections, but we’ve won every fight,” she said about the legislative agenda. “We’ve won every fight on the omnibus spending bill — you know the appropriations bills and the rest. You look at everything, they have no victories!”

And as the commentary seems to be coming to realize, that barrenness reflects more than Trump’s ineptitude as a leader; it is the product of deep and perhaps irresolvable divisions within the Republican Party.

Second, there seems to be an increasing awareness of the gap between Trump’s words and his deeds. As the New York Times reports this morning: “Mr. Trump’s expansive language has not been matched by his actions during this opening phase of his presidency.” The Washington Post adds:

“This is not a ‘buck stops here’ president,” said Douglas Brinkley, a presidential historian at Rice University. “His language is Trumanesque — unflinching and ‘Here’s what I’m going to do.’ But it’s just rhetoric. Once he tries to implement it as policy, he backs off. . . . He goes forward in a bully-boy fashion, but he gets his comeuppance.”

It’s not just that there is a gap between Trump’s words and deeds; it’s that his words are astonishingly weak, his rhetoric frequently impotent. Its main effect, often enough, is to get people to think the opposite—and to get others to do the opposite.

To take just one of the many recent examples: Trump was on Twitter Thursday, threatening to pull the plug on Puerto Rico, claiming that it had screwed up its finances and time was running out on helping the US territory and more than 3 million American citizens.

It was vicious, vile stuff, the kind of thing we have come to expect from Trump. What effect did it have? Within hours, the Republican-dominated House voted 353-69 to provide $36.5 billion—nearly $8 billion more than Trump had wanted—in disaster relief for Puerto Rico and other areas hit by hurricanes and wildfire. In this instance, Trump had the assistance of the Heritage Foundation, the powerful Republican lobby, which was strongly pushing Republican lawmakers to vote against the relief bill. To no avail. That’s how powerful Trump’s words can be.

In the coming weeks leading up to the anniversary of the election, expect to see more of this kind of commentary: the thinness of Trump’s first year in power, the gap between his rhetoric and action, the incoherence of the Republican Party and the contradictions of the conservative movement.

I mention all this for two, somewhat self-serving—well, very self-serving—reasons.

First, I’ve been flagging these themes from the beginning of Trump’s presidency. Despite being completely, as in utterly, wrong about the results of the November election, I have been right about what Trump’s regime would look like. Even before Trump’s Inauguration, I was setting out the possibilities of an incoherent, disjunctive presidency, one that could be usefully compared to the presidency of Jimmy Carter. In March, I wrote a piece in the New York Times that saw the healthcare debacle as a window onto the growing “existential crisis” within the GOP. In May, I reminded readers in The Guardian that there is a yawning gap between what Trump says and what he does, and that we had better pay more attention to the latter. And in August, I described the civil war developing within the GOP, which has now come out fully into the open, and why it would not necessarily spell a new round of power for the conservative movement, the way civil wars once did.

(For other commentary on the Trump era, post-election, see these pieces in Harper’s (on the dangers of a left grounding its politics entirely on fear of and opposition to Trump), and in The Guardian (on how institutions are not the antidote to tyranny; on how the real endgame of the Republicans is control of the judiciary, and more on the healthcare debacle as an augury of conservative incoherence.)

None of these positions was obvious or conventional at the time: the day after the election, the fact that an ostensibly united Trumpist GOP had assumed control of all three elected branches of the federal government seemed to virtually everyone, from the left to the right, to be the herald of a new dawn—a new fascist dawn, according to many. But having immersed myself for nearly 20 years in the conservative canon and the conservative movement, I had a different reading of the tea leaves.

Which brings me to my second point.

As many of you know, I have a new book out: The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Donald Trump. I say it’s a new book, and not a second edition, because as Dan Denvir pointed out to me in an interview on The Dig (soon to be broadcast), it really is a new book! Beyond a lengthy new chapter on Trump, the book is radically different in that, as the estimable Tim Schenck put it to me in this interview, “in the first edition of the book, war was clearly the dominant theme. In the new edition, you spend a lot more time on markets.” The struggle within the right over capitalism is now a major element in the book , animating nearly half the chapters. Trump is the culmination—or, depending on your view, denouement—of that struggle.

You can get a sneak preview of these themes in various venues.

n+1 has published a lengthy excerpt from The Reactionary Mind in its current issue. Here’s a taste:

The cold war allowed — or forced — the right to hold these tensions between the warrior and the businessman in check. Against the backdrop of the struggle against communism abroad and welfare-state liberalism at home, the businessman became a warrior — Robert Welch parlayed his career as a candymaker into a crusade at the John Birch Society — and the warrior a businessman. Caspar Weinberger went from the Office of Management and Budget and the defense contractor Bechtel to the Pentagon and Forbes. His nickname, “Cap the Knife,” captured the unified spirit of the cold-war self: one part accountant, one part killer.

With the end of the cold war, that conflation of roles became difficult to sustain. In one precinct of the right, the market returned to its status as a deadening activity that stifled greatness, whether of the nation or of the elite. American conservatism, Irving Kristol complained in 2000, is “so influenced by business culture and by business modes of thinking that it lacks any political imagination.” The idea of the free market was so simple and small, sighed Bill Buckley, that “it becomes rather boring. You hear it once, you master the idea. The notion of devoting your life to it is horrifying if only because it’s so repetitious. It’s like sex.” But in another precinct, market activities were shorn of anticommunist trappings and revalorized as strictly economic acts of heroism by a class that saw itself and its work as the natural province of greatness and rule. Donald Trump hails from the second precinct, but with a twist: his approach suggests there is no heroism in business — only deals.

…

Yet there is an unexpected sigh of emptiness, even boredom, at the end of Trump’s celebration of economic combat: “If you ask me exactly what the deals I’m about to describe all add up to in the end, I’m not sure I have a very good answer.” In fact, he has no answer at all. He says hopefully, “I’ve had a very good time making them,” and wonders wistfully, “If it can’t be fun, what’s the point?” But the quest for fun is all he has to offer — a dispiriting narrowness that Max Weber anticipated more than a century ago when he wrote that “in the United States, the pursuit of wealth, stripped of its religious and ethical meaning, tends to become associated with purely mundane passions, which often actually give it the character of sport.” Ronald Reagan could marvel, “You know, there really is something magic about the marketplace when it’s free to operate. As the song says, ‘This could be the start of something big.’” But there is no magic in Trump’s market. Everything — save those buttery leather pants — is a bore.

That admission affords Trump considerable freedom to say things about the moral emptiness of the market that no credible aspirant to the Oval Office from the right could.

…

TRUMP IS BY NO MEANS the first man of the right to reach that conclusion about capitalism, though he may be the first President to do so, at least since Teddy Roosevelt. A great many neoconservatives found themselves stranded on the same beach after the end of the cold war, as had many conservatives before that. But they always found a redeeming vision in the state. Not the welfare state or the “nanny state,” but the State of high politics, national greatness, imperial leadership, and war; the state of Churchill and Bismarck. Given the menace of Trump’s rhetoric, his fetish for pomp and love of grandeur, this state, too, would seem the natural terminus of his predilections. As his adviser Steve Bannon has said, “A country’s more than an economy. We’re a civic society.” Yet on closer inspection, Trump’s vision of the state looks less like the State than the deals he’s not sure add up to much.

As I mentioned, I did an interview with Tim Shenk at Dissent about the new edition. Tim got into some deep territory—Hayek, Burke, Hannah Arendt, public intellectuals, the “hate-fuck” of the right—and it’s worth listening to the whole thing. Or reading the edited transcript.

I also did an interview with Chuck Mertz of “This Is Hell!” It was a lot of fun and really gets into the nitty-gritty of my argument about Trump and why the Republicans are in the situation they are currently in.

I have more interviews in the works, so stay posted for updates on the blog. There are also reviews, I’m told, coming out, so again, stay posted.

There are two book events that you’ll also want to mark on your calendars.

On Monday, November 13, at 7 pm, I’ll be talking with Keith Gessen about the book at McNally Jackson in Soho. Keith is a novelist, a contributor to The New Yorker and the New York Review of Books, and a founding editor of n+1.

On Wednesday, November 15, at 7:30 pm, I’ll be talking with Eddie Glaude about the book at the Brooklyn Public Library in, well, Brooklyn (at Grand Army Plaza). Eddie is a professor of religion and African-American Studies at Princeton, author of several books on pragmatism, African-American thought, and American politics, and one of the most incisive and forceful commentators on contemporary politics and ideas.

Oh, and buy the book!

October 13, 2017

Philosophers, Politicians, Political Theorists, and Social Media: The Arguments We Make

Some people respond to only the best form of an argument. They tend to be philosophers.

Some people respond to only the worst form of an argument. They tend to be politicians.

Some people respond to something in between, to the non-best form of an argument. They tend to be political theorists, or at least political theorists like me. The reason being that the non-best is the argument that lives. It’s the argument that has traction and energy. It’s the argument that is truly political: the philosopher and the politician feed off it. Its non-best-ness needs to be understood on its own terms, as a phenomenon in its own right.

Then there are people who respond to and critique an entirely fanciful form of an argument that they have constructed completely in their own heads. They tend to be on social media.

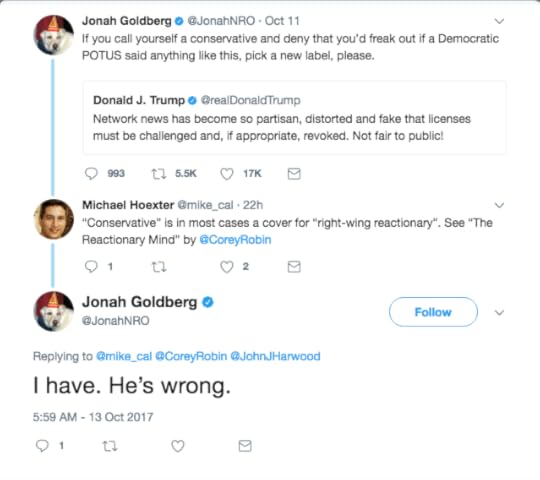

Oh, Jonah: If only conservatives knew their own tradition, Part LXXVII

Jonah Goldberg had this little exchange on Twitter on this morning.

I wonder if Jonah has ever read Section 2 of the Sedition Act.

SEC. 2. And be it farther enacted, That if any person shall write, print, utter or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or published, or shall knowingly and willingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them, or either or any of them, the hatred of the good people of the United States…then such person, being thereof convicted before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years.

The champion—many claim the author—of that bill in Congress was Theodore Sedgwick, president pro temp of the Senate. The president who eagerly and happily signed it into law was John Adams. Both conservatives in good standing.

October 12, 2017

Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand At Work: The Harvey Weinstein Story

Of all the sentences I’ve read on the Harvey Weinstein story, this one, from the New York Times, was the most poignant:

More established actresses were fearful of speaking out because they had work; less established ones were scared because they did not.

In virtually every oppressive workplace regime—and other types of oppressive regimes—you see the same phenomenon. Outsiders, from the comfort and ease of their position, wonder why no one inside the regime speak ups and walks out; insiders know it’s not so easy. Everyone inside the regime—even its victims, especially its victims—has a very good reason to keep silent. Everyone has a very good reason to think that it’s the job of someone else to speak out.

Those at the bottom of the regime, these less established actresses who need the most, look up and wonder why those above them, those more established actresses who need less, don’t speak out against an injustice: The more established have power, why don’t they use it, what are they afraid of?

Those higher up the ladder, those more established actresses, look down on those at the very bottom and wonder why they don’t speak out against that injustice: They’ve got nothing to lose, what are they afraid of?

Neither is wrong; they’re both accurately reflecting and acting upon their objective situations and interests. This is one of the reasons why collective action against injustice and oppression is so difficult. It’s Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand at work (in both senses), without the happy ending: everyone pursues their individual interests as individuals; the result is a social catastrophe.

October 11, 2017

What do the NFL and Trump’s Birth Control Mandate Have in Common? Fear, American Style

The Wall Street Journal reports that the NFL may adopt a policy to force football players to stand for the national anthem as a condition of employment.

It’s worth recalling that as a matter of constitutional right, a six-year-old student in this country cannot be required to stand for the Pledge of Allegiance or the national anthem. But a grown man or woman can be forced by their employer to do so. That should tell you something about the state of rights in the workplace. A state-run institution like the public school cannot stop you from sitting down during the pledge, but a private employer can.

The one factor that may stop the NFL from forcing the players to stand up during the national anthem? The players have a union.

It’s not just the NFL that’s confronting this issue of workplace rights. Late last week, the Trump administration decided to get rid of the birth control employer mandate. Employers now have the right, as a matter of religious freedom, to deny their workers insurance coverage for birth control. (Prior to this announcement, more than 50 million women had access to such coverage.)

As is true of the pledge and the national anthem, the state can’t deny you the right to use your insurance to buy birth control. Your employer can.

I wrote a long piece about that a few years ago: “Birth Control McCarthyism,” I called it. I charted there the long history of private coercion in this country, and how the right transposed that coercion into a matter of religious freedom.

Here it is in full:

Climbing aboard the anti-birth control bandwagon, the Arizona Senate Judiciary Committee voted 6-2 on Monday to endorse legislation that would: a) give employers the right to deny health insurance coverage to their employees for religious reasons; b) give employers the right to ask their employees whether their birth control prescriptions are for contraception or other purposes (hormone control, for example, or acne treatment).

As I argue in “The Reactionary Mind,” conservatism is dedicated to defending hierarchies of power against democratic movements from below, particularly in the so-called private spheres of the family and the workplace. Conservatism is a defense of what I call “the private life of power.” Less a protection of privacy or property in the abstract, as many conservatives and libertarians like to claim, conservatism is a defense of the rights of bosses and husbands/fathers.

So it’s no surprise that the chief agenda items of the GOP since its string of Tea Party victories in 2010 have been to roll back the rights of workers — not just in the public sector, as this piece by Gordon Lafer makes clear, but also in the private sector — and to roll back the reproductive rights of women, as this chart, which Mike Konczal discusses, makes clear. Often, it’s the same Tea Party-controlled states that are pushing both agendas at the same time.

What I hadn’t predicted was that the GOP would be able to come up with a program, in the form of this anti-birth control employer legislation we’re now seeing everywhere, that would combine both agenda items at the same time.

I should have foreseen this fusion because, as I argued in my first book, “Fear: The History of a Political Idea,” in the United States it has historically fallen to employers rather than the state to police the political opinions and practices of citizens. Focused as we are on the state, we often miss the fact that some of the most intense programs of political indoctrination have not been conducted by the government but have instead been outsourced to the private sector. While fewer than 200 men and women went to jail for their political beliefs during the McCarthy years, as many as two out of every five American workers were monitored for their political beliefs.

Recall this fascinating exchange between an American physician and Tocqueville during the latter’s travels to the United States in the early 1830s. Passing through Baltimore, Tocqueville asked the doctor why so many Americans pretended they were religious when they obviously had “numerous doubts on the subject of dogma.” The doctor replied that the clergy had a lot of power in America, as in Europe. But where the European clergy often acted through or with the help of the state, their American counterparts worked through the making and breaking of private careers.

If a minister, known for his piety, should declare that in his opinion a certain man was an unbeliever, the man’s career would almost certainly be broken. Another example: A doctor is skilful, but has no faith in the Christian religion. However, thanks to his abilities, he obtains a fine practice. No sooner is he introduced into the house than a zealous Christian, a minister or someone else, comes to see the father of the house and says: look out for this man. He will perhaps cure your children, but he will seduce your daughters, or your wife, he is an unbeliever. There, on the other hand, is Mr. So-and-So. As good a doctor as this man, he is at the same time religious. Believe me, trust the health of your family to him. Such counsel is almost always followed.

While all of us rightly value the Bill of Rights, it’s important to note that these amendments are limitations on government action. As a result, the tasks of political repression and coercion can often be — and are — simply outsourced to the private sector. As I wrote in “Fear“:There is little mystery as to why civil society can serve as a substitute or supplement to state repression. Civil society is not, on the whole, subject to restrictions like the Bill of Rights. So what the state is forbidden to do, private actors in civil society may execute instead. “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation,” Justice Jackson famously declared, “it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.” But what star in our constitutional constellation forbids newspapers like the New York Times, which refused during the McCarthy years to hire members of the Communist Party, from prescribing such orthodoxy as a condition of employment? What in the Constitution would stop a publisher from telling poet Langston Hughes that it would not issue his “Famous Negro Music Makers” unless he removed any discussion of Communist singer Paul Robeson? Or stop Little, Brown from refusing to publish best-selling Communist author Howard Fast?

The Sixth Amendment guarantees “in all criminal prosecutions” that the accused shall “have the assistance of counsel for his defence.” But what in the Constitution would prevent attorney Abe Fortas, who would later serve on the Supreme Court, from refusing to represent a party member during the McCarthy years because, in his words, “We have decided that we don’t think we can ever afford to represent anybody that has ever been a Communist?”

The Fifth Amendment stipulates that the government cannot compel an individual to incriminate herself, but it does not forbid private employers from firing anyone invoking its protections before congressional committees. To the extent that our Constitution works against an intrusive state, how can it even authorize the government to regulate these private decisions of civil society? What the liberal state granteth, then, liberal civil society taketh away.

Let’s come back now to the birth control employer question. Thanks to the gains of the feminist movement and Griswold v. Connecticut, we now understand the Constitution to prohibit the government from imposing restrictions on access to birth control. Even most Republicans, I think, accept that. But there’s nothing in the Constitution to stop employers from refusing to provide health insurance coverage for birth control to their employees.

And here’s where the McCarthy specter becomes particularly troubling. Notice the second provision of the Arizona legislation: Employers will now have the right to question their employees about what they plan to do with their birth-control prescriptions. Not only is this a violation of the right to privacy — again, not a right our Constitution currently recognizes in the workplace — but it obviously can give employers the necessary information they need to fire an employee. If a women admits to using contraception in order to not get pregnant, there’s nothing in the Constitution to stop an anti-birth control employer from firing her.

During the McCarthy years, here were some of the questions employers asked their employees: What is your opinion of the Marshall Plan? What do you think about NATO? The Korean War? Reconciliation with the Soviet Union? These questions were directly related to U.S. foreign policy, the assumption being that Communist Party members or sympathizers would offer pro-Soviet answers to them (i.e., against NATO and the Korean War). But many of the questions were more domestic in nature: What do you think of civil rights? Do you own Paul Robeson records? What do you think about segregating the Red Cross blood supply? The Communist Party had taken strong positions on civil rights, including desegregating the Red Cross blood supply, and as one questioner put it, “The fact that a person believes in racial equality doesn’t prove that he’s a Communist, but it certainly makes you look twice, doesn’t it? You can’t get away from the fact that racial equality is part of the Communist line.” (Though Ellen Schrecker, from whose book “Many Are the Crimes” I have taken these examples, points out that many of these questions were posed by government loyalty boards, she also notes that the questions posed by private employers were virtually identical.) The upshot, of course, was that support for civil rights came to be viewed as a Communist position, making public support for civil rights a riskier proposition than it already was.

It’s unclear what the future of birth control McCarthyism will be, but anyone who thinks the repressive implications of these bills can be simply brushed aside with vague feints to the religious freedoms of employers — more on this in a moment — is overlooking the long and sordid history of Fear, American-Style. Private employers punishing their employees for holding disfavored views or engaging in disapproved practices (disapproved by the employer, that is) is the way a lot of repression happens in this country. And it can have toxic effects, as Liza Love, a witness before the Arizona Senate committee, testified:“I wouldn’t mind showing my employer my medical records,” Love said. “But there are 10 women behind me that would be ashamed to do so.”

In the debate over the legislation, Arizona Republican Majority Whip Debbie Lesko (also the bill’s author) said, “I believe we live in America. We don’t live in the Soviet Union.” She’s right, though perhaps not in the way she intended: Unlike in the Soviet Union, the government here may not be able to punish you simply for holding unorthodox views or engaging in disfavored practices (though the government can certainly find other ways to harass or penalize you, if it wishes). What happens instead is that your employer will do it for the government (or for him- or herself). As the president of Barnard College put it during the McCarthy years, “If the colleges take the responsibility to do their own house cleaning, Congress would not feel it has to investigate.”

The standard line from Republicans and some libertarians is that requiring religious or religion-related employers (like the hospitals and universities that are funded by the Catholic Church) to provide health insurance coverage for their employees’ birth control is a violation of their First Amendment rights to religious freedom. The same arguments have come up in Arizona. Just after she made the comparison above between the United States and the Soviet Union, Lesko added:

“So, government should not be telling the organizations or mom and pop employers to do something against their moral beliefs.”

…

“My whole legislation is about our First Amendment rights and freedom of religion,” Lesko said. “All my bill does is that an employer can opt out of the mandate if they have any religious objections.”

…

Father John Muir, a priest at the All Saints Catholic Newman Center on the Tempe campus, said the controversial issue is not about birth control, but religious freedom and the First Amendment.

“It’s not about birth control,” Muir said. “It’s about the right to live out your beliefs and principles without inference by the state.”

There are many reasons to be wary of this line of argument, but the history of the Christian right provides perhaps the most important one of all. It’s often forgotten that one of the main catalysts for the rise of the Christian right was not school prayer or abortion but the defense of Southern private schools that were created in response to desegregation. By 1970, 400,000 white children were attending these “segregation academies.” States like Mississippi gave students tuition grants, and until the Nixon administration overturned the practice, the IRS gave the donors to these schools tax exemptions. And it was none other than Richard Viguerie, founder of the New Right and pioneer of its use of direct-mail tactics, who said that the attack on these public subsidies by the civil rights movement and liberal courts “was the spark that ignited the religious right’s involvement in real politics.”

According to historian Joseph Crespino, whose essay “Civil Rights and the Religious Right” in “Rightward Bound: Making America Conservative in the 1970s” is must reading, the rise of segregation academies “was often timed exactly with the desegregation of formerly all-white public schools.” Even so, their advocates claimed to be defending religious minorities — and religious beliefs — rather than white supremacy. (Initially nonsectarian, most of these schools became evangelical over time.) Their cause, in other words, was freedom, not inequality; not the freedom of whites to associate with other whites (and thereby lord their status and power over blacks), as the previous generation of massive resisters had foolishly and openly admitted, but the freedom of believers to practice their own embattled religion. It was a shrewd transposition. In one fell swoop, the heirs of slaveholders became the descendants of persecuted Baptists, and Jim Crow a heresy the First Amendment was meant to protect.

So it is today. Rather than openly pursue their agenda of restricting the rights of women, the GOP claims to be defending the rights of religious dissenters. Instead of powerful employers — for that is what many of these Catholic hospitals and universities are — we have persecuted sects.

Knowing the history of the rise of the Christian right doesn’t resolve this debate, but it certainly does make you look twice, doesn’t it?

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers