Corey Robin's Blog, page 31

August 3, 2017

The very thing that liberals think is imperiled by Trump will be the most potent source of his long-term power and effects

John Harwood has a good piece about Trump’s downward spiral of weakness:

Increasingly, federal officials are deciding to simply ignore President Donald Trump. As stunning as that sounds, fresh evidence arrives every day of the government treating the man elected to lead it as someone talking mostly to himself.

…

“What is most remarkable is the extent to which his senior officials act as if Trump were not the chief executive,” Jack Goldsmith, a top Justice Department official under President George W. Bush, wrote last weekend on lawfareblog.com.

“Never has a president been so regularly ignored or contradicted by his own officials,” Goldsmith added. “The president is a figurehead who barks out positions and desires, but his senior subordinates carry on with different commitments.”

…

The disconnect between Trump’s words and the government’s actions has been apparent for months.

Coming on the heels of yesterday’s Quinnipiac poll—showing Trump’s approval ratings at an all-time low (33%), with drops in support among Trump’s triad of support: men (40%), whites without college degrees (43%), and Republicans (75%)—and two week’s worth of articles demonstrating an increasingly restive Republican Party in Congress bucking Trump’s will (on Russia, war powers, health care, Jeff Sessions, and more), Harwood adds one more tile to the developing mosaic of Trump’s epic fail of a presidency.

It seems like we’ve gone, in a mere six months, from to this meme/scene from April 1945—

—without any of the promised the features in between: no Reichstag Fire, no Enabling Act, no Night of the Long Knives, and so forth.

Meanwhile, as I’ve argued before, where Trump is actually having a lot of policy and personnel success—long-term success, of the sort that will be impossible to reverse by his successors—is in appointing judges. While Trump has managed to reverse a lot of Obama’s regulatory regime, we should remember that that is the sort of thing presidents can do independently. And as Obama has now discovered, what one president can do, his successor can undo. And vice versa.

Judges are different. As Ronald Klain argued last month:

He [Trump] not only put Neil M. Gorsuch in the Supreme Court vacancy created by Merrick Garland’s blocked confirmation, but he also selected 27 lower-court judges as of mid-July. Twenty-seven! That’s three times Obama’s total and more than double the totals of Reagan, Bush 41 and Clinton — combined. For the Courts of Appeals — the final authority for 95 percent of federal cases — no president before Trump named more than three judges whose nominations were processed in his first six months; Trump has named nine. Trump is on pace to more than double the number of federal judges nominated by any president in his first year.

Moreover, Trump’s picks are astoundingly young. Obama’s early Court of Appeals nominees averaged age 55; Trump’s nine picks average 48. That means, on average, Trump’s appellate court nominees will sit through nearly two more presidential terms than Obama’s. Many of Trump’s judicial nominees will be deciding the scope of our civil liberties and the shape of civil rights laws in the year 2050 — and beyond.

Which makes for an interesting irony.

Since Trump’s election, we’ve heard a lot of concern from intellectual and journalistic worthies about the dangers of populism. What might a strongman armed with the instruments of the people and propaganda—legislatures, rallies, speeches, and tweets—do? Specifically, what might he and his populist crowds do to the courts, ever upheld as the bastions of liberty against a rampaging, marauding people?

As it turns out, that question gets it exactly backward. It’s not what Trump will “do” (in the sense of illicit browbeating or intimidation) to the courts that matters; it’s what the courts will do for him and his legacy that matters. Far from strongarming an independent judiciary into submission, Trump will secure his legacy simply by nominating judges and having them approved by the Senate, exactly as the Constitution prescribes.

It will be the independent judiciary, the Constitution, the counter-majoritarian Senate, the rule of law—all those instruments and institutions, in other words, that the Trump-as-fascist crowd loves to uphold as the safeguards of freedom or as imperiled flowers of the moment—that will be the most critical sources of Trumpism’s long-term power and effects.

In America, who’s more likely to win an election: a scam artist or a war hero?

This campaign commercial for Amy McGrath, who is running for Congress in Kentucky, has got the Twitterati excited.

The campaign of McGrath seems in line with a decision, leaked last June, by the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee to field candidates who had seen combat, along with “job creators” and “business owners.”

The question is: does it work?

In the last ten presidential elections, only one candidate who actually fought in a war has won: George HW Bush.

All the rest either served their country by shooting flicks (Reagan) or manipulating family connections or deferments to avoid combat (Clinton, George W. Bush, Trump) or simply weren’t eligible for a draft (Obama).

Meanwhile, enlistees, soldiers, and war heroes, Republican and Democrat alike, have repeatedly lost: Mondale, Dukakis, Dole, Gore, Kerry, and McCain.

In the most spectacular face-off’s between a genuine war hero and a draft-dodger-ish type—Clinton v. George H.W. Bush in 1992, George W. Bush v. John Kerry in 2004—it was the draft-dodger-ish type that won. (And if you think the same rules don’t apply at the congressional level, just google the names Max Cleland and Saxby Chambliss. Though as Matt Countryman pointed out, Tammy Duckworth is an excellent counterpoint to my claim.)

Despite our sense that Americans respond best to warriors and war heroes, it may be the confidence man who commands the most confidence. Something has shifted in this country. Whether it’s the passing of World War II as a touchstone of the political imagination or the end of the Cold War or the rise of neoliberalism, the elections of the last several decades have shown that while the consultant class and the image-makers continue to fantasize about an electorate cobbled together from a Spielberg film and a Sorkin script, the citizenry is far more taken by the conman and the scam artist than they are by the virtuous soldier.

Yet the dream dies hard, particularly among Democrats.

I get that this commercial is supposed to be different: a woman candidate, discriminated against, defending health care and the like. But, still, the main message is in the visuals and voiceover of that first minute of the video—all aircraft carriers and bombers, with the punch line being this: “I flew 89 combat missions bombing Al Qaeda and the Taliban.”

My gut sense is: it doesn’t work. It doesn’t even work for Republicans anymore. Just ask Bob Dole. Or John McCain.

August 1, 2017

The Bane of Bain

Back in 2012, Barack Obama made so much hay out of Mitt Romney’s connection to Bain Capital that a distraught Cory Booker was inspired to cry out, “Stop attacking private equity. Stop attacking Jeremiah Wright.” Booker called Obama’s attacks “nauseating” and “ridiculous,” which earned him a supportive tweet from John McCain.

Fast-forward to 2017. The Obama people are now pushing hard for Deval Patrick, the former two-term governor of Massachusetts, to run for the Democratic nomination in 2020. Guess what Patrick has been doing since he left the governor’s mansion? Working at Bain Capital.

It’s something. The combined forces of Wall Street and the Hamptons—sorry, Clinton and Obama—are pushing hard, variously, for Joe Biden (who’s making strong noises that he’ll be running in 2020), Kamala Harris, and Deval Patrick.

What do these three people have in common? None of them is the most popular politician in the United States.

July 31, 2017

Why John Kelly won’t—in fact, can’t—save Trump

Here’s how you know Kelly can’t and won’t impose discipline on the White House, notwithstanding the bold-not-so-bold-out-of-the-gate move of firing Scaramucci. Anyone who would take this job, thinking that he—unlike everyone else before him—can somehow make Trump into what Trump is not, thinking that what Trump really wants is to be saved from himself (remember, Trump is 71 years old; he’s not really in the market for a change of life), suffers from the same magical thinking that is at the heart of Trump’s entire operation. Kelly is not an answer or alternative to Trump; he is Trump.

July 29, 2017

Chelsea and Me: On the politics—or non-politics or pseudo-politics—of engaging a power player on Twitter

Let me preface this post with a disclaimer: I’m probably as embarrassed as you are—in fact, more embarrassed, I’m sure—that I’ve devoted as much thought to this tempest in a teacup as I have. But having poured this much thought into this little tea, I feel that I should share, lest my cup spilleth over. So here goes.

I’m finding the pushback—at this blog, on Twitter, and across Facebook—about my exchange with Chelsea Clinton super interesting. One of the leitmotifs of the pushback is that it’s somehow unfair of me to engage Clinton about Arendt. Now that it was an act of almost spectral comedy, if not lunacy, to so engage, I’ll freely admit. Which is mostly why I posted the whole exchange. But unfair? That tells me something about my critics. A lot of things, in fact.

But before I tell you about those things, let me say this: I didn’t actually seek out this exchange. I retweeted what Clinton wrote with a comment, a snide comment, as I admitted. I didn’t direct my comment at her, issuing a challenge and expecting a response. I was as surprised as anyone that she would see it, much less respond to it. But having gotten her response, I had a choice: ignore her or respond to her. I opted to respond, but as I said earlier, I deliberated about the proper mode of response. And decided I should respond the way I would to anyone else who gets something wrong. Which is what I did (politely, you’ll see; once she engaged, I tried to keep things on the up and up). I thought democratic manners required nothing less. And it was not I but she who kept the conversation going, returning to it again and again, long after I had assumed it was over.

But here’s what I’m thinking about the pushback.

First, had this exchange occurred with a Republican, or with one of the sons or daughters of a famous Republican, say Eric or Ivanka Trump, I have no doubt that I’d be hearing nothing but lusty cheers and congratulations, particularly from Democratic Party partisans. I mean these are folks who manage to muster a fresh cackle at every prodigy of stupidity the right manages to produce on any given day. But Chelsea Clinton is part of the team, so, well, the obvious. And that’s fine; I don’t begrudge people their partisanship. But I do ask that they cop to it and not pretend that I’ve somehow transgressed a norm they’d never acknowledge if the other party were on the receiving end of it.

Second, there’s a related element that’s worth noting. And that has to do with the politics of intelligence/education, social class, and partisanship. The Democratic Party and its supporters like to think of themselves as the party of the smarties. Obama, Clinton, Clinton, Clinton: all so smart, all so well educated, all so well spoken. That’s why they’re entitled to rule, their supporters think. (Believe me, I’ve had these conversations many times.) And that’s not just about politics; it’s also about social class, or at least the culture and style and markers of a particular kind of social class. Unlike the Trumps and other vulgarians of the right, these are people who know how to carry on a conversation at a cocktail party or on Charlie Rose. (Is that show still on, by the way?) Indeed, a well educated liberal person on Twitter—a professor of political science, in fact—made a point of noting to me that none of the Trump kids had read Hannah Arendt. That Clinton didn’t seem to get Arendt didn’t matter. It was enough that she had read Arendt. Or knew to show that she had read Arendt.

I’ll confess, I find that kind of thing distasteful. (Arendt has a great line in Eichmann about how the well-heeled educated German classes of the postwar era didn’t really have a problem with the fact that the workaday Jews of Germany—little Hans Cohn from around the corner was how, I think, she put it—had been murdered during the Holocaust; it was that Einstein had been sent packing. That was the real crime: the loss of all that wondrous cultural capital.)

My objection is not just academic or aesthetic or cultural; it’s also political. I don’t believe in technocracy. I don’t think I (or people like me) am qualified to lead the country or to have a Clinton-like position in this country because I went to good schools or read a lot of books. There’s a limited place for expertise in a democracy, but it’s limited. I know I’m in the minority here on this, but I get no comfort from the fact that Barack Obama reads great literature (that was a Facebook post a while back) or that Chelsea Clinton knows how to name drop Arendt. For me, that doesn’t reflect the legitimate needs for some limited expertise. Nor does it reflect the requirements of good leadership, and it sure as shit is not about democracy. It’s about social class, social standing, and social signaling.

In any event, a lot of the pushback from certain quarters seems to have more to do with that, with the anxiety around the role of intelligence and social signaling in the Democratic Party and liberal social circles, than it does with the ethics (or aesthetics) of engaging with Chelsea Clinton on Twitter about Arendt. To that extent, I not only think my criticism of Clinton is fair game—after all, if you think a source of liberalism’s cultural and political legitimacy is that liberals know something, it seems only fair to point out when they’re full of shit—but I also now have come to think that, despite the fact that I mostly posted about the exchange because I found it hilariously strange and amusing, it may serve a useful if limited political purpose.

Which brings me to a third point. The celebrity dimension. Some folks on Facebook and elsewhere don’t like that. I get it. Were I reading these posts, I might also think to myself, eh, big deal, he’s talking to Chelsea Clinton, why he’s going on about it? How is that helping The Cause? He should be spending his time on something else.

I guess all I’ll say in my defense is: give me a fucking break. I spend most of my time on social media getting into the minutiae of the politics of the healthcare bill, rounding up folks to make phone calls to their senators, making historical comparisons between Trump and other presidents, writing about whatever books I’m reading, reporting on what I’ve found in a Clarence Thomas opinion or some obscure text in political economy, and for about 18 months there, posting on Hannah Arendt.

For the most part, I avoid virtually every single sectarian intra-left internet spat. I don’t drone on about Chapo or the Jacobins and their haters or whatever bit of leftbook celebrity esoterica is currently preoccupying people on social media. I don’t get caught up in whatever atrocity of the day has the Twitterati chattering. Nor do I chastise other folks who do get caught up in that. I just try to stay focused on the things that matter to me and leave others to their thing.

So I think I’ve earned my right to a moment’s levity, and a slightly self-mocking post about my one-time engagement with a player like Clinton. To me, as I said, it’s funny. You may disagree; that’s fine. But I think we can both agree that the republic will survive these 24 hours of my indulgence. And while I do appreciate all the well-intentioned people who feel duty-bound to tell me that I would be better served spending my time on other things, I do wonder how they square that position with the fact that they’re spending all this time enjoining me not to spend all this time on this thing.

And for those who are simply annoyed that people around you are talking about this when you just couldn’t give a shit, I feel your pain. All I can say is: welcome to my world. That’s just the way it sometimes goes on the internet.

Fourth, the gender dimension. In the initial draft of my blog post, I had a long discussion about mansplaining and why I didn’t think that was what was at play here. After reading it over, I thought, oh, don’t go there. You can’t win this argument, not on the internet; you’ll only generate more accusations of mansplaining. Leave it out, leave it alone. So I did. And I will.

Fifth and final, the power dimension. I get the strong feeling that some people still think Chelsea Clinton is a little kid in the White House, getting her every pre-teen face and every teenage gesture subjected to nasty scrutiny from the right. People, Chelsea Clinton is nearing 40 years old. She’s a high-powered player in New York financial, cultural, and educational circles. She’s the leader of a major global foundation. And she’s increasingly a major player in national political circles. She has elected to be in the public eye. Those more than one million followers of hers on Twitter didn’t just happen. She’s created that audience, that following. I’m not going to play little ole’ me here, but I am in fact a professor at Brooklyn College; I don’t just play one on TV. The idea that I’m somehow this big powerful person who’s victimizing a hapless Chelsea Clinton is, well, a little silly.

I was going to close this post with a line from Smith—where he talks about how odd it is that people lower down on the totem pole always identify with the misery of their social superiors, seeing in abjection of elites some kind of universal state of disrepair or perhaps even their own misery—but I figured, nah, why elevate this like that? Instead, I’ll close with a plea that we all of us grow up and stop pretending that Chelsea Clinton is some poor little lamb who has lost her way and who needs protection from the likes of me. She’s already got Jordan Horowitz playing wing man for her; I think she’ll survive my tweets.

Yesterday, I got into an argument with Chelsea Clinton. On Twitter. About Hannah Arendt.

Yesterday, I got into an argument with Chelsea Clinton. On Twitter. About Hannah Arendt.

It began with Clinton tweeting this really upsetting story from the Washington Post about a man who set fire to a LGBT youth center in Phoenix. The headline of the piece read:

Man casually empties gas can in Phoenix LGBT youth center, sets it ablaze

Here’s what Clinton tweeted, along with that headline.

The banality of evil: https://t.co/BbhxhmGl0q

— Chelsea Clinton (@ChelseaClinton) July 28, 2017

I didn’t think Clinton was using Arendt’s concept of “the banality of evil” correctly. I retweeted her with some snide commentary.

This is what happens when you know something as a cliche or slogan rather than as an idea. Totally the opposite of what Arendt meant. https://t.co/Rh8jT7jlct

— corey robin (@CoreyRobin) July 28, 2017

Sidwell Friends, Stanford, Oxford, Columbia: all that money for fancy schools, and nowhere did you learn the meaning of this phrase?

— corey robin (@CoreyRobin) July 28, 2017

To my surprise, Clinton’s didn’t appreciate my commentary.

No, let me rephrase that.

To my surprise, Chelsea Clinton—author of a best-selling book; vice chair of a powerful global foundation; former special correspondent for NBC; possible congressional candidate, with a net worth of $15 million; daughter of the former president of the United States; daughter of the former Secretary of State and almost-president of the United States—read my tweet.

To my even greater surprise, Chelsea Clinton had an opinion about my tweet.

And to my even greater greater surprise, Chelsea Clinton responded to my tweet.

Hi Corey-Did you watch the video or read the article? Comment wasn’t about the headline. Thankful to have read Arendt at Sidwell & Stanford

— Chelsea Clinton (@ChelseaClinton) July 28, 2017

How do you respond to Chelsea Clinton? On Twitter? About Hannah Arendt?

I thought about that a bit.

And then it hit me: The way you respond to any mistaken comment on Twitter about Hannah Arendt.

So I re-read the article, just to make sure I hadn’t missed anything the first time around, and tweeted my reply.

I read the article, which suggests the arsonist is mentally unbalanced or has a personal beef. How do you think that holds up your claim?

— corey robin (@CoreyRobin) July 28, 2017

Now I need to make a detour and explain something about Eichmann in Jerusalem.

One of the key questions Arendt takes up in that book is: What motivated Eichmann to help organize the mass murder of the Jews?

Was he crazy?

No, says Arendt.

Half a dozen psychiatrists had certified him as “normal”—”More normal, at any rate, than I am after having examined him,” one of them was said to have exclaimed, while another had found that his whole psychological outlook, his attitude toward his wife and children, mother and father, brothers, sisters, and friends, was “not only normal but most desirable”…Behind the comedy of the soul experts lay the hard fact that his was obviously no case of moral let alone legal insanity.

Did Eichmann personally hate the Jews?

No, says Arendt.

His was obviously no case of insane hatred of Jews, of fanatical anti-Semitism or indoctrination of any kind. He “personally” never had anything whatever against Jews; on the contrary, he had plenty of “private reasons” for not being a Jew hater.

This, as virtually every reader of Arendt knows, was one of her more controversial moves, and it has plagued her and discussion of her book ever since. But regardless of one’s position on Arendt’s argument, it’s a relatively well known fact—certainly well known to anyone who’s read the book—that one of the central postulates of the book is that Eichmann’s crimes cannot be explained by his personal animus to the Jews.

According to the original Washington Post piece that Clinton was referencing, the Phoenix arsonist had once used the services of the LGBT youth center. From 2013 to 2016, when, the article reports, he turned 25 and “aged out.” So why did the arsonist do it? The article doesn’t reach any conclusions, but it strongly suggests that the man is mentally unstable and in desperate need of some kind of psychiatric care.

“This news hurts,” executive director Linda Elliott said in a news conference Wednesday. “Obviously this young man has issues and needs help.”

…The center staff last made contact with him about two months ago. He apparently also sought services at other organizations in the Valley.

…

A number of the young people who come to One-n-Ten struggle with mental illness and behavioral health problems.

Virtually nothing in the story is suggestive of the banality of evil. Not the arsonist’s motives. Nor his deeds: one of the major issues of contention in and around the Eichmann trial as well as Eichmann in Jerusalem was that this was a man who had sent millions of people to their death, without ever (or hardly ever; I’d have to re-read the whole book to say for sure), lifting a hand against them. Eichmann’s crimes were not ones of personal or direct violence; they were of a completely different order.

So that’s why, to get back to my exchange with Clinton, I tweeted that I had read the article but still wondered why she thought it held up her claim regarding the banality of evil.

Hours went by. I didn’t hear back from her, which is exactly what I would have expected.

I mean, if I were Clinton, I wouldn’t be wasting my time with me.

But I’m not Clinton, so I did waste my time with me. I tweeted out a few other comments about the strangeness of this exchange (one of which I’ll come to below).

Then, on Friday night—Friday night!—Clinton came back to the conversation.

With this:

Anyone who commits arson “casually” or not “needs help.” In 2017, the “casually” reminded me of @PeterDreier piece https://t.co/NTl19OFgLW

— Chelsea Clinton (@ChelseaClinton) July 28, 2017

Remember, Clinton had opened this exchange with the assertion that she wasn’t responding to the headline of the article but to something in the article itself, not conveyed in the headline. Now she was claiming the opposite: she was responding to the headline.

I replied.

Ah, so you were in fact responding to the headline after all.

— corey robin (@CoreyRobin) July 29, 2017

I also thought about tweeting that nothing in Eichmann in Jerusalem suggests that Arendt believes Eichmann was casual about his crimes. In fact, as Arendt goes to great lengths to show, he was extraordinarily meticulous and conscientious about his crimes, demonstrating great initiative and care in their execution. He took his “duty” to organize the mass murder of Jewish men, women, and children very seriously.

But I figured, eh, it’s Friday night, let it go.

Also, I figured we were done.

We weren’t.

Remember, earlier in the day, while Clinton was off doing more important things than arguing with me—On Twitter. About Hannah Arendt—I had been tweeting random thoughts about how surreal, almost lunarly surreal, this whole exchange was.

This was one of my tweets:

When do I get to start including in my bio “Once argued with Chelsea Clinton on Twitter about the meaning of Hannah Arendt”?

— corey robin (@CoreyRobin) July 28, 2017

Kinda lame, I know, but I was kinda flabbergasted—I’d say gobsmacked, but that word annoys me—by the fact that I was arguing with Chelsea Clinton. On Twitter. About Hannah Arendt.

Anyway, on Friday night, Chelsea Clinton returned to that tweet. With this response:

Now? Never? The increased level of hate crimes & desensitization to violence to me is redolent of Arendt’s caution. Will read your article.

— Chelsea Clinton (@ChelseaClinton) July 29, 2017

That article she’s referencing is this one. Someone on Twitter had pointed her to it.

But that reference to the desensitization to violence in Eichmann in Jerusalem: What was she talking about?

In Eichmann, Arendt had argued almost the opposite.

When Eichmann learned of the planned extermination of the Jews, Arendt says that he was shocked. He proceeded to cope with that knowledge, and the role he was to play in the Holocaust, not by desensitizing himself to violence but by wrapping his actions and deeds in all manner of “language rules”—euphemisms, jargon, and the like—that prevented him from knowing not what it was that he was physically, actually doing (that, he always knew: organizing the mass murder of the Jews) but the moral significance of what he was doing.

And even then, as Arendt goes on to point out in excruciating detail, when he was brought face to face with the actuality of violence, when the facts broke through that scrim of words that was built to disguise the meaning of those facts, Eichmann couldn’t take it.

The system [of language rules], however, was not a foolproof shield against reality, as Eichmann was soon to find out….

Shortly after this, in the autumn of the same year, he was sent by his direct superior Müller to inspect the killing center in the Western Regions of Poland that had been incorporated into the Reich, called the Warthegau. The death camp was at Kulm (or, in Polish, Chelmno), where, in 1944, over three hundred thousands Jews from all over Europe, who had first been “resettled” in the Lódz ghetto, were killed. Here things were already in full swing, but the method was different; instead of gas chambers, mobile gas vans were used. This is what Eichmann saw: The Jews were in a large room; they were told to strip; then a truck arrived, stopping directly before the entrance to the room, and the naked Jews were told to enter it. The doors were closed and the truck started off. “I cannot tell [how many Jews entered], I hardly looked. I could not; I could not; I had had enough. The shrieking, and…I was much too upset, and so on…I then drove along after the van, and then I saw the most horrible sight I had thus far seen in my life. The truck was making for an open ditch, the doors were opened, and the corpses were thrown out, as though they were still alive, so smooth were their limbs. They were hurled into the ditch, and I can still see a civilian extracting the teeth with tooth pliers. And then I was off—jumped into my car and did not open my mouth any more.

Page after page, Arendt narrates incidents and encounters like these. And nowhere does she question Eichmann’s veracity in telling of these encounters. (Though she does seem to question or mock his legal strategy: as if he could slip out of the hangman’s noose by showing that despite being a self-confessed mass murderer, he somehow didn’t enjoy the work.)

Desensitization to violence, in other words, was not one of Eichmann’s problems, at least as Arendt saw it.

I pointed some of these passages out to Clinton.

Except she argues that Eichmann didn’t get desensitized to violence. He could barely tolerate the sight of it, she said. pic.twitter.com/WwUNr0x9vV

— corey robin (@CoreyRobin) July 29, 2017

And that, mercifully, was the end of it.

Except for this guy.

Honestly? All of you people are just being assholes. Find something better to do with your times/lives.

— Jordan Horowitz (@jehorowitz) July 28, 2017

So she can’t possibly know/understand Arendt because *you* are the one who knows/understands Arendt. Got it.

(FYI I have never read Arendt)

— Jordan Horowitz (@jehorowitz) July 28, 2017

I haven’t read Arendt. But she was talking about the headline. She made that clear.

— Jordan Horowitz (@jehorowitz) July 29, 2017

Who is Jordan Horowitz, you may ask?

He’s this guy.

Remember the Academy Awards this year, when at first it seemed that La La Land had won, then it turned out that Moonlight won? That guy in the video, announcing this sudden plot twist at the Oscars, was Jordan Horowitz, co-producer of La La Land.

And that’s Jordan Horowitz protecting Chelsea Clinton—author of a best-selling book; vice chair of a powerful global foundation; former special correspondent to NBC; possible congressional candidate, with a net worth of $15 million; daughter of the former president of the United States; daughter of the former Secretary of State and almost-president of the United States—from me.

So why am I telling you all this?

Because I still can’t go over the fact that yesterday, I got into an argument with Chelsea Clinton. On Twitter. About Hannah Arendt.

We have in this country a really weird ruling class.

Update (4:20)

Originally, I had a different conclusion, based on a series of tweets that I thought were Clinton’s but turned out to be a parody account (thanks to the good people of Twitter who pointed that out to me and saved me from even more embarrassment!) Ordinarily, when I make a mistake or error on this blog, I simply strike through the mistake. In order not to hide the error or pretend that I didn’t make it. I would have done that in this case, but since 3/4 of what I had were tweets from that parody account, and you can’t do strike-through’s with tweets, I’ve simply deleted the whole thing. Sorry for the confusion.

Update (5:55)

People seem to be confused by my update. Let me try this again. In the original post, there were a few (as in three) tweets at the VERY END of the post that turned out to be from a parody account. You can see what those posts were in the links that I provide in my update at 4:20. All the other tweets from Clinton which I respond to in this blog—i.e., EVERY TWEET YOU’VE JUST BEEN READING ABOVE, BEFORE THE UPDATE—is a real tweet from Clinton. In other words, I did have an exchange with Clinton, which you’ve just read here.

July 24, 2017

The Democrats: A party that wants to die but can’t pull the plug

Yesterday, I noted my exasperation, in the face of the economic desperation of the younger generation, with the Clintonites in the Democratic Party. Young men and women are drowning in massive debt, high rent, low pay, and precarious jobs, and what do the Democrats have to offer them?

In today’s Times, Chuck Schumer, the highest elected official in the Democratic Party, gave an answer:

Right now millions of unemployed or underemployed people, particularly those without a college degree, could be brought back into the labor force or retrained to secure full-time, higher-paying work. We propose giving employers, particularly small businesses, a large tax credit to train workers for unfilled jobs. This will have particular resonance in smaller cities and rural areas, which have experienced an exodus of young people who aren’t trained for the jobs in those areas.

Tax credits to employers to train unskilled workers.

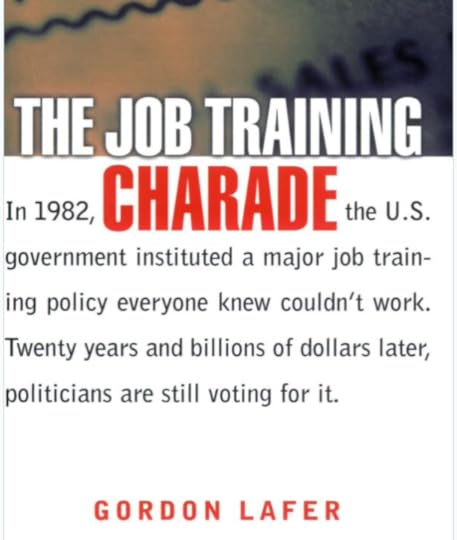

Do you know how old and ancient and bullshit this idea is? Here’s how old and ancient and bullshit this idea is. When, more than a decade ago, the University of Oregon political scientist Gordon Lafer came out with his landmark study The Job Training Charade, demonstrating how poorly these job training programs had performed over the years, he reached back, on the cover of the book, to a 1982 bill that essentially promised to do what Schumer is now proposing to do.

There’s one difference. Where the 1982 bill focused on government programs and partnerships, Schumer’s bill seems to focus exclusively on tax giveaways to employers, already awash in cash.

Why did Lafer feature that bill on his cover? Because despite decades of data and research showing how bad these programs were, they held an unusual attraction to Republican and Democratic legislators alike. Co-sponsors of that 1982 bill ranged from right-wingers like Paula Hawkins and Thad Cochran (remember them?) and Orrin Hatch to liberals like Teddy Kennedy. Job training, Lafer showed in exhaustive detail, has come to be the neoliberal salve for our free-market age. When you can’t do anything else for workers, train them. For jobs that aren’t there or wages that suck.

It’s true that Schumer offers other proposals, including a $15 minimum wage, but for anyone with a memory, the devotion of one sentence, much less a paragraph, of precious column space to this synecdoche of the bipartisan political economy of the last four decades—well, it’s enough to make you think this is a party that wants to die but can’t pull the plug.

July 23, 2017

The Millennials are the American Earthquake

This is a super-fascinating article for multiple reasons.

First, it turns out millennials are even more like the 1930s generation than we realized. Not just in their politics, as Andrew Hartman recently argued, but also in their economic practices. Having come of age during an epic financial crisis, they’re now staying away from the stock market, and putting their money in savings accounts—the equivalent, during the Depression, of stuffing your dollar bills in a mattress for fear of there being a run on the banks.

These little gestures signal deep cultural shifts that are ultimately really important for politics. My generation was raised to think that the stock market was our savior. Fuck pensions and Social Security! You can’t trust the state or the long-term future. You can get much better returns from the whiz kids on Wall Street. That millennials are rejecting that kind of message seems hugely significant to me.

I’ve been saying for years that I would love to see a contemporary version of Edmund Wilson do what he did during the Depression: go and report on the everyday life of the Financial Crisis and its aftermath, seeing how the mood and manner of this generation has been fundamentally altered and reshaped by that experience. It may not be quite The American Earthquake—yet—but there certainly are tremors (what Wilson called, in the book’s first iteration, “the American jitters.”)

Second, that the Post thinks millennials earning $40,000 a year have tons of extra disposal income to sock away for their futures seems risible. Given rents and job precarity and student loans that have to be paid off, it seems totally rational to me that a young person in today’s economy would want to be assured that they’ll have money for food and rent come next month. Better to keep it in the bank than tie it up in a long-term index fund or whatever. Having the money near at hand seems perfectly understandable.

Third, the freakout from the Post and the investor class over this is delicious. Wall Street has ever been the antenna of the nation. It registers —inadvertently, unconsciously—movements and shifts that aren’t always apparent to the eye. Not just economic movements but also cultural and political ones. As Jevons said:

Just as we measure gravity by its effects in the motion of a pendulum, so we may estimate the equality or inequality of feelings by the decisions of the human mind. The will is our pendulum, and its oscillations are minutely registered in the price lists of the markets.

What the market is telling us is: the motion of the pendulum is moving in a different direction, the will of this new generation is not like that of its recent predecessors.

Update (9:45 am)

Just a few minutes out, and I’m already seeing tons of responses to this on Twitter and Facebook. Young people telling their personal stories—with precision, concreteness, detail—of their struggles in this economy. I find it all unbelievably poignant.

It just makes me all the more enraged at the Clinonite blather you hear on social media. And not just the Clintonites; it’s also the left. What in the end do we on the left have to offer people today? Medicare for All and free college. Don’t get me wrong; these would be great, and I’ve been fighting for them, too. But they don’t touch the fundamentals of the economy. I don’t mean that in a Marxist sense.

Just think of everyone from the New Dealers to Bill Clinton: all of them had a theory of the economy and how it might improve people’s lives and standing. Clinton’s was bullshit, but he was the last one to even think he had to offer a comprehensive account to people. Perhaps that was due to the hangover from the Cold War, which is now over. Without the challenge of communism, we don’t think we need to give people something like a vision of the economy.

So we let this generation die. We bury them, without having even the decency to perform an autopsy or deliver a eulogy.

July 21, 2017

All the president’s men were ratfuckers

On MSNBC, former Bush White House Communications Chief Nicolle Wallace went after the new White House communications director Anthony Scaramucci and his team: “These are not all the president’s men, these are all of Sean Hannity’s men.”

I gather Wallace thinks “all the president’s men” means men of great virtue and talent, the proverbial Wise Men of the early Cold War or the Knights of the Roundtable or something.

In reality, the phrase refers to Nixon’s team of White House advisors and convicted Watergate felons, all of whom went to jail: Haldeman, Erlichman, Mitchell, Colson, Chapin, and Segretti, who literally invented the phrase “ratfucking” for the dirty tricks he was hired to do for the Nixon campaign.

It’s also a riff on Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men—a fictional account of one of America’s great and most dangerous demagogues—not to mention a famous poem by Lewis Carroll nursery rhyme, where the entire point is that all the king’s horses and all the king’s men couldn’t put Humpty back together again. Not the most efficacious bunch, in other words.

The ever present need to believe in some mythical past of American virtue—particularly at liberal media outlets like MSNBC, where Bush White House officials are refurbished as honorable elders of state*—inevitably produces a history where we’re forever defining deviancy downward.

Meanwhile, Wallace has this to say about Trump: “He knows scant presidential, or frankly world history.”

* Thanks to Dave Daley for that point.

We have the opportunity for a realignment. We don’t have a party to do it. Yet.

One of the interesting things about the great realignment elections—1860, 1932, 1980—is that the presidents who win them (Lincoln, FDR, Reagan) never run simply against the losing candidate. Nor do they run simply against the party of that candidate. They run against a decades-long regime, which is never simply a party or political regime, but always, also, a social regime. Lincoln ran against the slaveocracy, who had nested in the Democratic Party. FDR ran against the economic royalists, who had found their protectors and agents in the Republican Party. Reagan ran against a complex of “special interests” (civil rights organizations, unions, feminist groups, poverty programs) that had captured the Democratic Party. In repudiating Carter, Hoover, Breckinridge/Douglas—and the Democrats of 1980, the Republicans of 1932, and the Democrats (Southern and Northern) of 1860—Reagan was really repudiating the special interests, FDR was really repudiating the economic royalists, and Lincoln was really repudiating the slaveocracy. You could hear this in their words, and see it in their deeds.

The reason these realignment presidents do this is not simply because they want to gut what they view as a malignant social formation. It’s that they are presented with, and don’t hesitate to seize upon, a golden opportunity when the candidate/party that represents those social formations is at a historically low ebb. The Democrats were fractiously divided between two candidates and two regions in 1860. Hoover and Carter were haplessly presiding over economic crises. Lincoln and the Republicans, FDR and the Democrats, Reagan and the Republicans: all were shrewd enough to see and seize upon their moment. In part because all those candidates and parties had undergone a radical internal transformation (in the case of Lincoln and the Republicans, that involved a break with preexisting parties and the formation of a new party). In order to topple these regimes, these realignment presidents first had to come to power through a major faction fight within or without their party, where they forced one faction to give way to another.

Realignments, in other words, are what are called, in fancy terms, conjunctures. You have an immediate political or economic crisis that, in the hands of the right kind of party, gets turned into a repudiation of decades of rule and misrule and a broader social malignancy. It’s not enough to have a crisis: the 2007 Financial Crisis didn’t generate a realignment; the Democratic Party, despite Obama’s rhetoric, wasn’t interested or ready for that. Things certainly were pushed to the left—relative to both Bush and Clinton—but it wasn’t a realignment. No, it’s not enough to have a crisis; you need a party and persons ready to turn that crisis, rhetorically and politically, into a catastrophe that sets the stage for an entirely new mode of politics.

The great possibility—and potential peril—of the current moment is that we are once again presented with that kind of opportunity. It’s not simply that Trump and the Republicans are a walking disaster. Their disaster opens out onto—reveals—a much deeper social malignancy: the triumph of the business class. I’ve spent the entire morning reading article after article on the GOP’s plans on taxes, the budget, the debt, and the regulatory regime they’re trying to destroy. And what comes away more than anything else is the players. It’s not Bannon or Miller, both of whom seem to be completely sidelined. It’s not even Ryan or McConnell. Almost all of the players are straight from Wall Street, corporate America, the Chamber of Commerce, Heritage, and so on. And it is consistently their interests that are winning in the Trump administration.

What’s also revealed in these documents is just how incompetent and bad these guys are at their jobs. Steven Mnuchin—from Yale, Goldman Sachs, and more hedge funds than I can count—can’t do the simplest thing in Washington because he hails almost entirely from the very class that Republicans and neoliberal Democrats have been telling us for decades knows what it is doing. Remember, in the wake of the Financial Crisis, Obama’s smug and self-important defense of Lloyd Blankfein’s and Jamie Dimon’s multi-million-dollar, year-end bonuses? “I know both those guys; they are very savvy businessmen.” Well, as it turns out, those guys aren’t so savvy. And when they get political power, they’re even more clueless. That’s important for us to stress. Part of what gave FDR and New Dealers like Rexford Tugwell and Sidney Hillman such élan in the 1930s was their sense that the business class had thoroughly discredited itself. Their sense was: the economic royalists had their chance; it’s our turn now.

We have an amazing, once-in-a-half-century opportunity not simply to discredit and disgrace Trump or Ryan or McConnell or the Republican Party. We have an amazing, once-in-a-half-century opportunity to repudiate the entire business class. They are the authors of our current predicament. They are the doyens of our current moment. They are the social malignancy—like the slaveocracy, like the economic royalists—that needs to be repudiated.

But we can’t do that unless and until we either transform the Democratic Party, as Reagan and the right did with the Republicans in the 1960s and 1970s, or find and found a new party, as Lincoln and the Republicans did in the 1850s.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers