Corey Robin's Blog, page 25

July 23, 2018

The Question of Russia and the Left: A response to Ryan Cooper

For the past week, there’s been a lot of discussion on Russia, Putin, Trump, and how leftists are responding to the issue. I’ve been participating in these conversations on social media. This past weekend, the conversation got a little crazy, when Columbia Law lecturer and Harper’s contributor Scott Horton engaged in some wild and irresponsible speculation about how the Russians may be backing certain Democratic primary candidates in the current elections.

This morning, Ryan Cooper weighed in on the issue at The Week. I disagree with where he comes out on the issue.

I want to say at the outset that I consider Cooper an ally. I don’t know him personally, but I very much admire his work. We follow each other on social media, and frequently retweet each other’s articles and posts. We are engaged in the same project: we’re both in the Sanders wing of the left; we want to focus the political conversation on the economy, racial injustice, a less imperial foreign policy, and so on; we’re interested in the electoral possibilities for the left right now. As Ryan makes clear, he’s been pretty skeptical of parts of the Russia story, and though he’s reconsidered his position on that story, he does not want to make Russia the central item in the public conversation. He’s not a foaming at the mouth treason talk kind of guy.

So this is the comment of one lefty to another, who mostly agree with each other.

Ryan thinks the left needs to get serious about Russia and the interference in the election. It’s that move—the call to get serious (the phrases Ryan uses are “wise up” and “paying attention”)—that I don’t like. It’s so suffused with ambient noise—on the one hand, it’s a free-floating signifier of something more; on the other hand, it’s so free of specifics as to make it difficult to know precisely how to engage in it as a useful or practical discussion from the left—that it’s bound to generate more confusion, maybe acrimony, than to help us move forward. The left needing to get serious is the equivalent of the pink spot in The Cat in the Hat Comes Back: every time you try to wash it away, the spot just jumps on to whatever material you’re using to wash it away with. Every time you try “to get serious,” the need to get serious moves on to some other surface.

A fair amount of what Ryan writes here is unobjectionable and I don’t disagree with. I accept the story that the Russians hacked the election (by which I mean that they made attempts to hack into voter registration systems in the states, that they hacked the DNC and Podesta emails, and that they funded social media bots and the like); that they wanted Trump to win (not for any reasons of building an ethnonationalist alliance but simply because Clinton was clear throughout the campaign that she intended to break with Obama’s efforts to accommodate Russia and the Russians believed they’d be better off with Trump than with Clinton), and that their efforts were mounted in that direction. I don’t have a hard time accepting that account, at all.

The question is what follows from that. To my mind, it simply means beefing up cybersecurity efforts. I’ve pointed out on social media that money has already been allocated to the states to that effect, yet a lot of that money has not been spent. But there have been other bills and measures taken, which as Seth Ackerman has pointed out, have gotten almost no attention in these discussions (aside from one brief mention, Ryan gives them no attention at all). The left’s position on all this should simply be that prudential measures should be taken to ensure democratic elections—while always pointing out that if democratic elections is truly your big concern, there are many other more concrete threats to democratic elections in this country, starting with the Electoral College. Moreover, the left should hold not only the Republicans but also the Democrats accountable for those measures (some of these state legislatures where balloting systems are vulnerable are controlled by Democrats, and they’ve done very little about it).

But that’s not really where Ryan goes in this piece. Instead, he takes two different tacks.

One is to emphasize the political hay that can be made from attacking Trump as Putin’s Puppet.

Putin has dirt on Trump, and is using it to manipulate him. The way Trump behaves around Putin — quietly bowing and scraping, taking his word over America’s own chief of intelligence, and thus inciting backlash even from Republicans (not much of it, but more than usual) — is simply wildly out of character. It just does not add up. That’s the kind of simple, alarming narrative that might break through the noise. [Ryan is addressing those folks who say that the public doesn’t care about Russia. He’s saying they could care soon, particularly if we focus attention on it.] I strongly suspect that over the next six months to year, Russiagate will become a greater source of public attention, and therefore a decent potential vulnerability for Trump. If so, it would be senseless to avoid bringing that attack, in addition to a strong traditional policy program. You don’t have to be a frothing nationalist to be concerned that the president is taking dictation from some ruthless dictator.

I think this route is both wrong and dangerous. It’s wrong because as I have been posting over the week, close watchers of Russia and the US have pointed out all the multiple ways in which the US is currently pursuing a very anti-Russia foreign policy, more aggressive than anything pursued by Obama (especially Obama), Bush, or Clinton. Last week, NPR of all places did a story on precisely this, citing this comment from a foreign policy expert at the Atlantic Council:

When you actually look at the substance of what this administration has done, not the rhetoric but the substance, this administration has been much tougher on Russia than any in the post-Cold War era.

So the idea that Trump—by which I mean his administration (I’ll talk about him in a minute)— is simply taking dictation is empirically wrong.

It’s dangerous for two reasons. First, it fans the flames of nationalism and treason talk, resulting in the kind of rhetoric we saw over the weekend, where Scott Horton was essentially seeing any left candidacy as a manifestation of a potential Russian op (more on this in a second). I hate to invoke authority here, but I did write a book on the politics of fear, focusing specifically on cases where domestic politics and international politics intertwine, and this is dangerous terrain. You think you can control the rhetoric; it controls you.

Second, while I’m perfectly prepared to believe the Russians have something on Trump, my concern is that we get into a dynamic whereby politically to prove that they are not in hock to the Russians, the GOP, or the administration, are pushed to take increasingly hostile measures, foreign policy measures, that could get the US into worse shape and generate more tension with Russia. Trump himself won’t do much of anything beyond what he does already. But his administration and his party (which, remember, voted for heavy sanctions against Russia), will. And Trump’s shown almost no ability to stop them from doing so. It’s a bad dynamic.

So that’s one tack Ryan takes with which I disagree. The other tack he takes is to say that as the Democrats ascend, they’ll have to confront the threat of Russian hacking.

And whoever wins the 2020 Democratic primary — say Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders — is highly likely to face a serious campaign of dirty tricks from Russian intelligence. Email hacking will be attempted, any compromising past history dug up, and third-party candidates boosted up — all in an attempt to throw the election to Trump. It probably won’t move that many people, but Trump only won by less than 100,000 votes spread across three states. It’s a threat that needs to be reckoned with.

Now if all Ryan means is: let’s beef up cybersecurity and the like, fine. But he doesn’t really say that. Instead, by seeding the discussion of the 2020 election with all this talk of Russian intelligence and ops, by fanning the political flames rather than settling for quieter, more prudential calls for better cybersecurity, I fear that he underestimates, and perhaps contributes to, the paranoia this kind of argument can generate.

In any campaign, whether the Russians are involved or not, a candidate’s compromising history will be churned up. Remember the role Jeremiah Wright played in Obama’s campaign in 2008? Or the swift-boating of John Kerry? In any campaign, there is the possibility of third party candidates, getting boosted by writers, activists, and the like. Once you introduce the Russia question into all this, it becomes almost impossible to distinguish between someone bringing up a candidate’s compromising history as part of normal politics and someone doing that as a Russian op. Do we seriously want an American politics where good old-fashioned dirty pool—exposing someone’s embarrassing past—is suddenly cast as one element in the potential plot of a foreign power? That seems like not a good way to go.

Just to give you a historical parallel. During the McCarthy years, the security apparatus and anticommunists and well-meaning liberals obsessed over the question of how to detect who was a Communist and who wasn’t. The problem was that the Communist Party backed, indeed was in the forefront of, many progressive causes: desegregating the baseball league, desegregating the blood supply of the Red Cross, and so on. The more cynical of the red hunters came up with the Duck Test: if it looks like a duck, if it quacks like a duck, it’s a duck. In other words, if you were white and supported an array of progressive causes, odds are, you were a Communist, and in league with the Russians. It didn’t take a genius to realize that the most logical strategy was to avoid those causes. Which many people did. (Those causes were also helped by the Cold War, but that’s another story.)

Up until now, I’ve mostly resisted the McCarthyism parallels, in part because the term gets so misused for something like “unfair accusations,” and McCarthyism was considerably more than that, as I discuss in my book on fear. But now that the aura of Putin and his operations is hovering over wider and wider sectors of the left, and people like Horton are using that aura as a way of thinking about challenges to mainstream Democrats from the left, and we’re getting into this terrain of the duck test—where perfectly legitimate political activity (supporting third parties, digging up dirt on your opponent, supporting left candidates in primaries [this was Horton’s point]) comes to be tainted as foreign and a covert op of the Russians—I’m bringing it up because it seems relevant.

My approach to this, as I’ve said, is simply to have better security measures, and whatever you do, not to fan the flames of the discussion. So by all means, I strongly recommend that Ryan and others who are legitimately concerned about this, to use their platforms, every day, every week, to push both the Republicans and the Democrats (because, again, at the state level there is evidence that both parties are not taking care of this issue) to protect balloting systems, to beef up the cybersecurity, and all the rest. But I also think it’s imperative to avoid all this talk of third party candidates, of attacking candidates for their compromising history, and the like as somehow a Russian op. Because again, there’s no way to distinguish a candidate digging up dirt on another candidate, as part of the course of normal politics, from a Russian op. The only result will be more paranoia, more anxiety, and more delegitimation of perfectly legitimate political and electoral efforts, and as a result, a winnowing of the political space.

In the end, I’m really not sure what it is that Ryan would have us do and who in fact his audience is in this piece. I suspect it’s people like me (I don’t mean me literally, just people like me): While I’ve been very clear from the start that I think the Mueller investigation should go forward, while I’ve been perfectly open to the Russian interference story, it has certainly not been my passion, I do tend to think of it mostly as a distraction, and I’ve been hostile to and critical of the treason talk (both because I think it’s not true and because I hate nationalism).

But what would Ryan have me (or people like me) do? He’s not asking those of us on the left who have not joined in the Russia sky is falling chorus to support more aggressive cyber-security measures. He’s not asking us to push for a more confrontational approach with Russia (I don’t believe he supports that approach himself.)

It feels more as if we’re supposed to signal something in our rhetoric. Personally, I don’t like this kind of move in political arguments. It gets too close to: you need to show your bona fides, and I dislike that kind of politics. It’s a bit too much like virtue signaling. But even if that weren’t true, what would Ryan have us say? That we also think Trump is Putin’s Puppet? That we think this is part of an alliance of oligarchs (a claim I can’t make given the actual US foreign policy against Russia and the oligarchs right now.) I’ve said, I believe there is evidence for the interference, and I think that the answer is beefed up cybersecurity. Beyond that, I’m not willing to go or join in, for the reasons I’ve outlined. I think that should be enough.

And if there are some fundamental doubters or skeptics on the left about the interference story, I think that’s fine: either their doubt and skepticism will turn out to be useful (somehow we’ve all forgotten our John Stuart Mill here) or it won’t.

I suspect the real issue for some people on the left—not Ryan, but others I frequently read on this topic—is that they fear that that doubt and skepticism will make the left look bad. I’ll come clean on that: I have zero tolerance for people who take their political positions from a feared perception of how they might look otherwise, whose sense of politics is essentially a high school version of not wanting to seem un-cool. I left high school more than 30 years ago. I’m not going back.

I saw a lot of this after 9/11, particularly on the left: with people trying to prove their bona fides on their antipathy to terrorism and Islamism, just to show they could be as tough as the next guy. I have nothing but contempt for that kind of posturing. It’s craven—and embarrassing.

July 16, 2018

On Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Palestine, and the Left

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, whose candidacy I’ve championed and worked for since May, had a bad moment late last week.

Appearing on the reboot of Firing Line, Ocasio-Cortez was asked by conservative host Margaret Hoover to explain her stance on Israel. The question left Ocasio-Cortez tongue-tied and equivocating. Here was the exchange:

MH: You, in the campaign, made one tweet, or made one statement, that referred to a killing by Israeli soldiers of civilians in Gaza and called it a “massacre,” which became a little bit controversial. But I haven’t seen anywhere — what is your position on Israel?

AOC: Well, I believe absolutely in Israel’s right to exist. I am a proponent of a two-state solution. And for me, it’s not — this is not a referendum, I think, on the state of Israel. For me, the lens through which I saw this incident, as an activist, as an organizer, if sixty people were killed in Ferguson, Missouri, if sixty people were killed in the South Bronx — unarmed — if sixty people were killed in Puerto Rico — I just looked at that incident more through . . . through just, as an incident, and to me, it would just be completely unacceptable if that happened on our shores. But I am —

MH: Of course the dynamic there in terms of geopolitics —

AOC: Of course.

MH: And the war in the Middle East is very different than people expressing their First Amendment right to protest.

AOC: Well, yes. But I also think that what people are starting to see at least in the occupation of Palestine is just an increasing crisis of humanitarian condition, and that to me is just where I tend to come from on this issue.

MH: You use the term “the occupation of Palestine”? What did you mean by that?

AOC: Oh, um [pause] I think it, what I meant is the settlements that are increasing in some of these areas and places where Palestinians are experiencing difficulty in access to their housing and homes.

MH: Do you think you can expand on that?

AOC: Yeah, I mean, I think I’d also just [waves hands and laughs] I am not the expert on geopolitics on this issue. You know, for me, I’m a firm believer in finding a two-state solution on this issue, and I’m happy to sit down with leaders on both of these. For me, I just look at things through a human rights lens, and I may not use the right words [laughs] I know this is a very intense issue.

MH: That’s very honest, that’s very honest. It’s very honest, and when, you, you know, get to Washington and you’re an elected member of Congress you’ll have the opportunity to talk to people on all sides and visit Israel and visit the West Bank and —

AOC: Absolutely, absolutely. And I think that that’s one of those things that’s important too is that, you know, especially with the district that I represent — I come from the South Bronx, I come from a Puerto Rican background, and Middle Eastern politics was not exactly at my kitchen table every night. But, I also recognize that this is an intensely important issue for people in my district, for Americans across the country, and I think what’s at least important to communicate is that I’m willing to listen and that I’m willing to learn and evolve on this issue like I think many Americans are.

Let’s be clear. This is not good. Prompted about her use of the word “massacre,” Ocasio-Cortez doesn’t stay with the experience of the Palestinians. Instead, she goes immediately to an affirmation of Israel’s right to exist, as if Israelis were the first order of concern, and that affirming that right is the necessary ticket to saying anything about Palestine. Asked about her use of the phrase “occupation of Palestine,” Ocasio-Cortez wanders into a thicket of abstractions about access to housing and “settlements that are increasing in some of these areas.” She apologizes for not being an expert on a major geopolitical issue. She proffers liberal platitudes about a two-state solution that everyone knows are just words and clichés designed to defer any genuine reckoning with the situation at hand, with no concrete discussion of anything the US could or should do to intervene.

Even within the constraints of American electoral politics, there are better ways — better left ways — to deal with this entirely foreseeable question. Not only was this a bad moment for the Left but it was also a lost opportunity: to speak to people who are not leftists about a major issue in a way that sounds credible, moral, and politically wise.

As soon as I saw this exchange, I posted about it on Facebook. I said a shorter version of what I said above. It provoked a bitter debate on my page. There were even more bitter debates on other people’s pages.

The camps divided in two: on the one hand, there were those who took Ocasio-Cortez’s comments as confirmation that she is no real leftist, that she is turning right, that she’s been absorbed into the Democratic Party machine, that she’s a fake, a phony, and a fraud. For these folks, Ocasio-Cortez’s comments confirmed their generally dim view of electoral politics.

On the other hand, there were Ocasio-Cortez’s defenders, claiming that she is only twenty-eight, that she had been set up by a right-wing journalist, that progressives shouldn’t criticize her, that the Left always eats its own, that those of us who are criticizing her are sectarians ready to go after anyone the second they disappoint us.

What I’m about to say doesn’t address the first camp. While I know and respect many of these folks — leftists who either reject electoral politics completely or reject any involvement with the Democratic Party — theirs is not my position. Nor do I think this incident is revelatory one way or another for their position — had Ocasio-Cortez said all the right things, I doubt it would convince skeptics of electoral politics that getting involved in Democratic Party politics is the way to go — so I don’t see any point in using it to engage in that question.

My comments are directed to the latter camp: the people who, like me, believe in electoral politics, are on the Left, and think we may have an opportunity right now that we have not had in a long while.

There are some of us, many of us, who care deeply about the Israel/Palestine issue from an anti-Zionist perspective and who are also realistic about US electoral politics. We’re not naïfs who think that the politicians we support are going to come out right away, or right now, in support of a single binational democratic state, which is the position we hold with regard to Palestine. We also realize that the Left that is beginning to think about electoral politics is young (not in terms of age but political experience), and it will take us all some time to figure out how to advance our positions in a way that will win support and translate that support into policy.

And last, we know that despite the centrality of Palestine to our politics, it’s not central to the politics of everyone on the Left, that people have multiple concerns, and that it does no good simply to hector people and say this should be at the top of your list (along with a thousand other issues that should be at the top of your list).

I know all of that, we know all of that.

But we also know a few other things.

Sooner or later, every national politician in the US has to confront the issue of Palestine. You can’t duck it. Not only is the Left moving left on this issue, not only is the base of the Democratic Party moving left on this issue (it is, if you look at the polling), but it is also a major issue of international politics and US foreign policy that every member of Congress has to have a position on.

Palestine is not some obscure question that you can simply say, “Sorry, I don’t know much about that.” Any person who aspires to be a member of Congress, particularly from New York City, where this issue comes up as a local, national, and international issue all the time — when we had the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions fight at Brooklyn College in 2013, our top opponents included multiple members of the New York City congressional delegation: Jerry Nadler, Yvette Clark, Nydia Velazquez, and Hakeem Jeffries — will have to be clear about where they stand. It’s not optional: Ocasio-Cortez has to have a position.

Not only does Ocasio-Cortez have to have a position, but to be a credible leftist voice in Congress, she has to have a leftist position on this issue. Now, before everyone concludes that means she has to call for a binational state, there are many ways to talk left about Israel that are considerably better than the current liberal pabulum and that do not require an elected official to commit political suicide.

There is the human rights vernacular that Ocasio-Cortes herself alludes to (a particularly popular approach, as sociologist Ran Greenstein pointed out in the discussion on my Facebook wall). There is the language of realpolitik, which people like Nathan Thrall have pushed. And other ways still.

Ocasio-Cortez could talk about conditioning aid on human rights improvements. She could talk about cutting military funding to Israel. George H. W. Bush, after all, withheld loans to Israel because of the expansion of the settlements — not a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, but here in the US, in the early 1990s. All of these claims are well to the left of any current political discourse in Congress and would force the debate forward and would be productively polarizing. And maybe propel Ocasio-Cortez to even more of a leadership position on the Left.

This is not just about Palestine. This is about US foreign policy as a whole. It used to be that US foreign policy was the Left’s strong suit. Back in the 1970s, when it seemed as if the Left’s confidence in its economic policies and positions was flagging, its critiques of US imperialism, military spending, and the national security state were in ascendancy. Some of these positions even made it into the left wing of the Democratic Party. Since then, the Left has gotten very weak on this stuff. Not in terms of its moralism on foreign policy, or the antiwar rallies it will show up at, but in terms of being able to advance a position that would begin to command national assent, form public opinion, and then be translated into policy.

This is a problem: it should be the easiest thing in the world right now, for example, to go after runaway military spending. Yet there’s hardly a credible or potent left voice that is pushing that agenda, much less getting a hearing within even progressive circles of the Democratic Party. Indeed, in this age of alleged partisan polarization, authorizations of massive increases in spending for the Pentagon and the CIA pass both houses of Congress with hefty Democratic majorities — with scarcely anyone noticing, much less protesting.

So, again, this isn’t about Palestine only. Or I should say, Palestine is the proverbial canary in a coal mine. From Palestine you get into the question of the Middle East as a whole, which leads to US foreign policy as a whole, and issues of budgets, spending, war, peace, and all the rest. All the more reason for Ocasio-Cortez to get up to speed on it.

Like it or not, Ocasio-Cortez has been elevated to a national position of leadership and visibility on the Left. If she wins in the general election, as everyone believes she will, every single thing she says and does will be watched and scrutinized. It simply will not do to say, oh, she’s only twenty-eight, oh, the media is so nasty, oh, let’s not have circular firing squads. The media is always nasty, the Left will always be critical of its leaders, and one day, soon, Ocasio-Cortez will no longer be twenty-eight. To complain about any of these things is like shaking your fist at the weather (weather in the old-fashioned sense; before climate change).

People have turned to Ocasio-Cortez not simply because she won but because she’s good at what she does: she’s smart, fast, funny, and principled. Because she’s shown leadership. I understand the pressures she’s under. But as her star rises, the pressures will only increase. Ocasio-Cortez needs to be not only strong but also clear on this issue. She needs to be as subtle, dexterous, and sharp as she is on other issues, virtually every night on Twitter. This isn’t a game, especially when it comes to Israel. Or, if it is a game, she needs to be a better player.

What has sustained me the most in these last several years is the on-the-ground work of the activists, in Democratic Socialists of America and other groups, who have been making victories like Ocasio-Cortez’s possible. I’m confident that those folks are talking to her now about getting a better line on this, and I’m more than confident that she has the political skills to get it.

There was a time, not so long ago, when there were left Democrats, in Congress, who had strong anti-imperialist politics and positions. There were even parts of the Left — particularly the black left — that were critical of Israel at a fundamental level. They didn’t get there from nowhere. They weren’t better people. There was simply more of a movement, in the streets and at the grassroots, articulating and developing those positions. There is no reason we can’t do the same. I’m confident we will.

July 15, 2018

On Liars, Politics, Michiko Kakutani, Martin Jay, and Hannah Arendt

A long piece by Michiko Kakutani on “the death of truth” is making the rounds. In it, she quotes Arendt:

Two of the most monstrous regimes in human history came to power in the 20th century, and both were predicated on the violation and despoiling of truth, on the knowledge that cynicism and weariness and fear can make people susceptible to the lies and false promises of leaders bent on unconditional power. As Hannah Arendt wrote in her 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (ie the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (ie the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

Arendt’s words increasingly sound less like a dispatch from another century than a chilling description of the political and cultural landscape we inhabit today…

This is an Arendt quote that gets thrown around a lot these days, for obvious reasons, but it gives a very partial view of Arendt’s position on truth and lies. Sam Moyn pointed this out on Twitter. Sam also urged folks to read Martin Jay’s book on the question of lies and politics, which includes an extensive discussion of Arendt.

I haven’t read Jay’s book, but I did read a draft of it, or part of it, for a talk he gave at Columbia years ago. It was the Lionel Trilling Seminar, and I, along with George Kateb, was asked to be one of the discussants. I remember being a little discomfited by Jay’s treatment of Arendt. So I dug up my comment, and thought I’d reproduce it below. I think it suggests why Kakutani’s gloss is too simple, but also why Jay’s gloss (at least the earlier version of it; again, I didn’t read the final book) may be too simple, too.

The bottom line, for me, about Arendt’s treatment of lies and liars: one of the reasons she was so unnerved by liars was that the way they did politics was so close to how she thought politics ought to be done. She wasn’t endorsing lying or embracing liars. She just thought the distinction between the liar and the truth-teller was too easy because opposing oneself to reality—which is what the liar is doing, after all—is part of what it means to act politically. Part of what it means; not all of what it means. For as we’ll see, Arendt also thinks there is a necessary dimension of factuality that also undergirds our political actions. And that it is part of our job to preserve that factuality. And that it is between these two dimensions—preserving factuality, opposing oneself to factuality—that the political actor, and the liar, ply their trades.

By the way, I should note the date of that exchange with Jay: October 2008. We were still in the Bush era. The entire discussion—of lies and facts, the disregard for facts, and such—was framed by the Iraq War and the epic untruths that were told in the run-up to the war. It should give you a sense that the world of fake news that so many pundits seem to have suddenly awakened to as a newborn threat has been with us for a long time. The Bush era may seem like ancient history to some, but in the vast, and even not so vast, scheme of things, it was just yesterday.

Here are my remarks about truth and lies, Arendt and Martin Jay.

***

In the fall of my senior year in college, I decided to write my thesis on the Frankfurt School. Then I read Adorno. In a panic, I ran to my adviser, who said, “Read Martin Jay’s little book on Adorno.” I did, and it got me through Negative Dialectics. In the spring of my senior year, I concluded that the Frankfurt School was a dead end, politically, but that Hannah Arendt could lead us out of the impasse. Then I read Arendt. I ran to my adviser again. This time, he said, “Read George Kateb’s big book on Arendt.” I did, and it got me through The Human Condition. This a long way of saying that I’m extremely honored to be sharing a platform with Professors Jay and Kateb, to whom I owe a great debt, which I hope to begin paying back tonight, and that I’d like to thank the Heyman Center, and Professor Posnock in particular, for giving me the opportunity to do so.

In 1935, Bertolt Brecht wrote an essay on telling the truth. Given his own troubled relationship to the truth, it wasn’t a natural or easy topic for him. Sure enough, he titled his essay “Writing the Truth: Five Difficulties.” Tonight, Martin Jay offers us four defenses of lying. Five obstacles to the truth, four paths to lying. Those are some depressing numbers – until you consider the fact that when Montaigne thought about the problem of truth and lies, he could identify a hundred thousand paths to lying. So we’re doing better.

Even so, I’d like to take a closer look at – and perhaps complicate – one of Professor Jay’s defenses of lying: his third. It occupies a single paragraph in his text but, as we’ll see, a large part of his extremely stimulating argument.

The defense goes like this: Politics is a realm of dissonant opinions and conflicting interests. That is not a contingent or temporary feature of politics. It is a permanent and necessary condition, a reflection of the fact that we live among men and women who see the world from their own distinct – and often clashing – perspectives. Acting in such a world requires us to apprehend and incorporate those perspectives – not to issue diktats according to our inner lights or the light of truth. One does not – indeed one cannot – search for truth in politics. Truth is concerned with that which is, with what lies beneath the surface and cannot be changed, politics with flux and appearance. Truth is singular; politics plural. Truth is a monologue that demands silence and assent. Politics is a dialogue, which can only reach a consensus (and a provisional consensus at that) by assimilating the many, ever-changing opinions of its various voices. Once we recognize the inherently agonistic and dissonant nature of politics, we will see, in Jay’s words, that “sophistic rhetoric rather than Platonic dialectic is the essence of ‘the political.’”

So far, so Arendt. As Jay acknowledges, Arendt’s two essays, “Truth and Politics” and “Lying in Politics,” are the inspiration for his argument that truth and politics are in conflict, an argument that also underlies his second and fourth defenses of lying. But it is the last, almost unspoken, step of his argument – namely, that because politics cannot provide a home for truth, it should welcome lying as a returning prodigal son – that gives me some pause. For in making that step I wonder if Jay is taking Arendt somewhere she did not want to go and somewhere we may not want to go as well.

That last step in the argument – again, that because truth does not belong in politics, lying does – may conflate two types of truth that Arendt was at pains to keep apart: what she called rational truth and what she called factual truth. Although Jay briefly mentions this distinction, I’m not sure he gives it its full due.

For Arendt, rational truth – 2 plus 2 equals 4; Socrates’ maxim that it is better to suffer wrong than to do wrong; Kant’s categorical imperative – has all the characteristics of truth that Jay has so ably discussed here. For that reason it is, in Arendt’s words, “unpolitical by nature.”

Factual truth is different. Although it too is coercive and cannot be argued with – which hasn’t stopped some from trying – factual truth is, again in Arendt’s words, “political by nature.” To repeat: rational truth is “unpolitical by nature,” factual truth is “political by nature.”

Why is that so? While rational truths are derived by the philosopher in solitude and reflect his almost autistic* desire not to contradict himself, factual truths are, according to Arendt, “the invariable outcome of men living and acting together.” Factual truths refer to events, past or present, which result from men and women acting in the world. In order to be recorded and remembered, factual truths require the testimony of men and women who have witnessed those events. Factual truths also inform, or at least should inform, the opinions of men and women. For all of these reasons, factual truths “constitute,” in Arendt’s words, “the very texture of the political realm.”

The essence of political action, for Arendt, is to begin something anew, to change something in the world. In order to change something in the world, however, there has to be a world to change. Factual truths are that world. While factual truths are resistant to change – they refer to events that already have occurred, to occurrences that cannot be un-occurred – they also provide what Arendt called “the ground on which we stand and the sky that stretches above us.” In fact, it is only because factual truths are resistant to change that they give us a point from whence to begin and a destination beyond which we cannot go. Factual truth is the floor beneath – and the roof above – our actions. A house, if you will, or a home. Thus, where the coerciveness of rational truth is the enemy of politics, the coerciveness of factual truth provides a home for politics.

The opposite of rational truth is illusion or opinion, which finds its champion in the sophist. The opposite of factual truth is the falsehood or lie, which finds its spokesperson in, well, the liar. The sophist and the liar, in other words, are different animals, inhabiting different realms. Yet I worry that Jay may have melded them into one. And while it’s clear from Arendt’s essays that she had a soft spot for the sophist, for reasons that Jay has explained so well, she felt nothing but dread in the presence of the liar. Not only did she believe that he was the enemy of politics, tearing up the ground upon which we walk, but she also feared that he possessed two advantages in his war against politics, which might lead to his victory.

The first is that factual truth is more vulnerable than rational truth. While facts can be stubborn things once they come into being – it will always be true, for example, that Germany invaded Belgium in August 1914 – they remain permanently shrouded in the mists of contingency: Germany, after all, might not have invaded Belgium in August 1914; the United States might not have invaded Iraq in March 2003; Saddam Hussein might have possessed WMDs in February 2003. Factual truths never have to be what they are, and for that reason, are vulnerable to the liar’s claim that they aren’t. Factual truths also require the testimony of witnesses and the memory of men and women to remain in the world. Should enough people come to believe the liar’s claim, the facts about which he lies could be lost from the world forever. Not so rational truth: no matter how many of us come to believe that 2 plus 2 equals 5, it will remain true that 2 plus 2 equals 4, and it will only take some person in the future using his or her mind to summon that truth back into circulation.

The second advantage the liar possesses in his war against politics is that he himself is an actor and thus can easily operate behind enemy lines. He’s an actor in the literal sense, and politics, as both Arendt and Jay remind us, is a theater of appearances. But he’s also an actor in the political sense: he seeks to change the world, turning what is into what isn’t and what isn’t into what is. By arraying himself against the world as it is given to us, the liar claims for himself the same freedom that the political actor claims when he brings something new into the world: the freedom to say no to the world as it is, the freedom to make the world into something other than it is. It’s no accident that the most famous liar in literature is also an adviser to a man of power, for the adviser or counselor has often been thought of as the quintessential political actor. When Iago says to Roderigo, “I am not what I am,” he is affirming that the liar, the dramatic actor, and the political actor all subscribe to the same creed.

It’s interesting that Jay does not discuss this aspect of the liar – his refusal to accept the world as it is and his effort to render it as he would like it to be – for it is the one element in the liar’s profile that actually fits in the world of politics. If one wanted to talk, as Jay puts it, about “the ways in which politics…has an affinity for mendacity” – one might have begun here, with the liar – like the political actor – opposing himself against reality for the sake of changing it. One might have cited any of a number of statements from the Bush Administration in the lead-up to the Iraq War, all demonstrating that one of the reasons the liar is so comfortable in politics is that it is in the nature of political action to oppose what is for the sake of what is not. Or, as this exchange between George W. Bush and Diane Sawyer after the Iraq War had begun reveals, to conflate what is not with what is.

Sawyer: But stated as a hard fact, that there were weapons of mass destruction as opposed to the possibility that he [Saddam] could move to acquire those weapons.

Bush: So what’s the difference?

A more perfect – and, ironically, more honest – statement of the creed of the liar/political actor – not to mention the doctrine of preventive war – would be hard to find.

But Jay doesn’t discuss this dimension of the liar’s craft. And I wonder if the reason he doesn’t discuss it has something to do with the conclusion he wishes to draw at the end of his talk, when he says that “the search for perfect truthfulness is not only vain but also potentially dangerous. For ironically, the reversed mirror image of the Big Lie may well be the ideal of Big Truth, singular, monologic truth, which silences those who disagree with it.”

Hovering around the edges of Jay’s conclusion, if I’m reading him correctly, are the totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century, which murdered millions in order to make the world conform to the way they thought it really was, to make the world conform to their idea of truth. Jay’s defense of lying is in part a defense of the pluralist, agonistic world – filled with illusions, distortions, flaws, hypocrisies, and lies, yes, but open to contestation and correction. However imperfect or ugly that world may seem, particularly to the moralist, it is infinitely more attractive than are these total and terrible regimes of truth.

But that only raises the question: in the end, won’t the liar be compelled to walk down the same road as the totalitarian seeker of truth? The liar, after all, is not really an enemy of truth; he’s a parasite on truth. When he falsely but deliberately declares x to be the case, he wants and needs his audience to believe that x is indeed the case. He wants and needs his audience to believe that there is something called the truth, that he is telling it, and that they should heed him. And if he wants and needs his audience to believe these things, not just today, but tomorrow and the day after that, he’s going to have to turn his falsehood into reality. He’s going to have to make his lie come true. Having declared that a man named Trotsky never made the Russian Revolution, he’s going to have the man named Trotsky murdered. Having staked his presidency on the claim that Saddam Hussein has weapons of mass destruction, he’s going to have to wage war against Iraq in order to eliminate those weapons.

It’s this compulsion of the liar – that because he is a parasite on, rather than an enemy of, the truth, he will have to make his lie come true, often through violent and other nasty means – that makes him such a dangerous figure, next to whom the sophist is but a charming clown. And I fear that by conflating the two, Jay may have allowed the virtues – or at least the charms – of the one to obscure the vices of the other.

* On a re-read of this post, I just saw that I used the word “autistic” in the way that I did. Were I to have written this talk today (remember, this was a talk I gave in 2008), I would never use the term in that way. I was clearly not sensitized to the issue, and the language, at the time: I was using the word to mean something like self-absorption, removed from the communicative reality of other human beings, which is one of the associations the word once had, but given our growing knowledge of autism, it seems highly inappropriate and wrong to use the word in this fashion today. I thought about taking the word out, but since I had already posted the post, that seemed dishonest, as if I were trying to hide what I did. So I’ve crossed it out, noting my failure here, without erasing its traces. My sincere apologies and regrets.

July 9, 2018

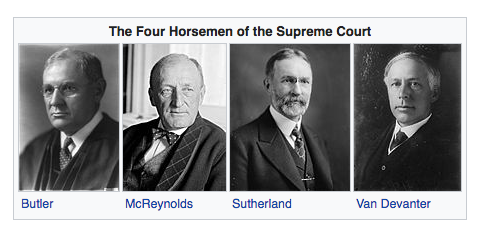

The Five Horsemen of the Apocalypse

During the Roosevelt Administration, they were known as the Four Horsemen (of the Apocalypse). They were Justices Butler, McReynolds, Sutherland, and Van Devanter. They voted, again and again, against the New Deal.

This is what they looked like.

Tonight, with Trump’s choice of Brett Kavanaugh, we have the Five Horsemen. They are Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and, once he’s confirmed, Kavanaugh. They will vote, again and again, against whatever progressive legislation Congress and the states manage to pass in the future.

This is what they look like.

July 6, 2018

Did Anthony Kennedy ever sniff glue? And other stories of nominations past

Last week, after Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement from the Supreme Court, Donald Trump declared, “Outside of war and peace, of course, the most important decision you make is the selection of a Supreme Court judge.” As we await Trump’s announcement on Monday of this most important decision, let’s take a gander at the history of nominations past.

1. In 1990, when George H.W. Bush was casting about to replace retired Supreme Court justice William Brennan, the consensus candidate in the White House was Ken Starr.

2. Starr got nixed by Dick Thornburgh, who was Bush’s Attorney General. Thornburgh thought Starr was too much of a squish, not sufficiently hard-right, especially about presidential power.

3. Today, Thornburgh is one of Trump’s most prominent conservative critics, claiming that Trump poses a radical threat to the rule of law and Republican values.

4. Bush settled on David Souter as his nominee.

5. Three years earlier, the Reagan White House had briefly considered Souter after Robert Bork’s nomination went down in flames.

6. Souter was scotched when Reagan’s people discovered he had joined a New Hampshire Supreme Court decision declaring that gay men and women had a constitutional right to run day-care centers.

7. Reagan settled on Anthony Kennedy instead.

8. Kennedy was considered safe. He offered the Reaganites reassuring answers to literally hundreds of questions about his personal life.

9. Among other questions, Kennedy was asked:

Did he have sex in junior high?

If he had sex in college, where did he do it?

Had he ever had sex with another man?

Did he ever have kinky sex?

Had he ever had herpes?

Did he sniff glue?

10. This is how constitutional law gets made. Before the norms eroded.

July 4, 2018

How eerie and unsettling it can be when people change their minds: From Thomas Mann to today

In the wake of the victory of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a number of people have been commenting, complaining, celebrating, noticing how quickly mainstream liberal opinion—in the media, on social media, among politicians, activists, and citizens—has been moving toward Sanders-style positions. And without acknowledging it. Positions, policies, and politics that two years ago were deemed beyond the pale are now being not only welcomed but also embraced as if the person doing the embracing always believed what he or she is now saying.

This, as you can imagine, causes some on the left no end of consternation. For some legitimate reasons. You want people to acknowledge their shift, to explain, to articulate, to narrate, perhaps to inspire others in the process. And for some less legitimate, if understandable, reasons: people are pissed at the way Sanders-style politics was attacked in 2016 and want folks to own up to it. Understandable, from a human point of view, but not really the way you build a coalition or a movement. If the left is going to grow, everyone should be welcome to join, without having to hand over a bill of lading upon their arrival.

But I’m not bringing this up to settle scores or to enforce some kind of norm of the welcome mat. I’m actually just super interested in this phenomenon, in this kind of change at the both the human and the political level. By “this kind of change” I don’t meant the deep transformations that a fair number of political people undergo over the course of a lifetime: the proverbial migration from left to right, for example, that we saw throughout the 20th century. That’s a deep, one-time change that you don’t easily go back from. I mean more these micro-shifts that happen under the pressure of events, the subtle coercions of new opinion, the ever-finer movements to keep up with where things are going, so as not to be left behind.

I just finished reading Thomas Mann’s letters, and Mann in many ways is an exemplary figure in this regard. Leading up to World War I, he was a fairly standard old-school conservative militarist/nationalist. That continued until the end of the war. After the war, he slowly became a dedicated liberal defender of Weimar. Once the Nazis took over, his liberalism morphed into staunch anti-fascism, humanist in its outlook. By the end of the war, that antifascism had come to include overt sympathy to communism and the Soviet Union (he even praised Mission to Moscow on aesthetic grounds!). That continued into the late 1940s, when he supported Henry Wallace for president and was outspoken in his opposition to HUAC and defense of the Communist Party in Hollywood and elsewhere.

But then, around 1950 or so, you see, ever so slightly and subtly, Mann’s opinions starting to change once again. He never comes out in defense of McCarthyism, but he slowly starts becoming more critical of the CP, of the Soviet Union, and less critical of the repression. Till finally, in a 1953 letter to Agnes Meyer, his close friend and matriarch of The Washington Post, he confesses that he has decided not to publicly oppose McCarthyism. He reports to her that when he was asked—”probably by someone on the ‘left'”—what he thinks about the censorship and restrictions on freedom in the US, he replied, “American democracy felt threatened and, in the struggle for freedom, considered that there had to be a certain limitation on freedom, a certain disciplining of individual thought, a certain conformism. This was understandable.”

It just about broke my heart. That “left” in scare quotes (previously he had seen himself as a part of the left), the clichéd endorsement of Cold War confinement, the betrayal of all that he had said and done in the preceding decades—and most important of all, the seeming inability to see that he was betraying anything at all.

Who was the real Thomas Mann? The German militarist, the Weimar liberal, the humanist antifascist, the Popular Fronter, the Cold War liberal? Who knows? All of them, none of them? I think in the end, his most authentic moment was probably in his combination of Weimar liberal and early antifascism, with its humanism. That was the one true shift (from early militarist to humanist liberal anti-fascist) that he could endure and narrate. But the rest of those shifts? That was just the way the game was being played. As the climate of opinion changed during the war, he changed with it. And then at the onset of the Cold War, he changed again. But watching how his positions changed—within a very short period of time—without him even realizing it, without him even remembering what he had said, a mere three years prior, was eerie and unsettling. And heart-breaking, as I said.

During the McCarthy years, Arendt wrote in a letter to Jaspers how terrified she was of the repression. Not just the facts of it but by how quickly the mood of the moment had gone from a generous and capacious liberalism to a cramped anticommunism. “Can you see,” she wrote, “how far the disintegration has gone and with what breathtaking speed it has occurred? And up to now hardly any resistance. Everything melts away like butter in the sun.”

We’ll never know what combination of incentives and forces and genuine beliefs are at play in one person’s shifting positions. And like I said, I welcome the change that is happening today. But I would be less than honest if I didn’t say that I was sometimes unsettled by it. Particularly when it’s unacknowledged.

Intellectuals like to think of themselves as above this kind of thing, but I think we’re especially prone to it. Intellectuals live in the world of ideas, with an emphasis on that word “world.” The world is not what goes on in our heads; it’s what’s happening out there, between heads. Intellectuals want to be in that space of the in-between (Arendt knew this more than anyone). They want to be in the swim. That can make them chameleons of the first order.

Intellectuals are probably not that different from anyone else in this regard, but they do like to take and defend positions as if they were emanations of pure reason. Or unblinkered empiricism. The proverbial “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” Which always gets attributed to Keynes but was in all likelihood said by Paul Samuelson.

I confess I’m always suspicious of these “when the facts change” types. In part because the most pressing fact that seems to change people’s opinions is…other people’s opinions.

Among intellectuals, that doesn’t always lend itself to an honest narration of change. Just the opposite: it can become an ever-shifting, ever-more baffling, and often unacknowledged, litany of changes.

Not sure what there is to be said about that. Just noting how universal, if sometimes eerie, it is.

June 6, 2018

The Creative Class Gets Organized

The staff of The New Yorker—the people behind the scenes: editors, fact checkers, social media strategists, designers—are unionizing. They’ve even got a logo: Eustace Tilly with his fist raised. If you’re a loyal reader of the magazine, as I am, you should support the union in any way you can. Every week, they bring us our happiness; we should give them some back. They’re asking for letters of solidarity; email them at newyorkerunion@gmail.com.

If you look at their demands, they read like a tableaux of grievances from today’s economy: no job security, vast wage disparities, no overtime pay, a lot of subcontracting, and so on.

The creative class used to see itself and its concerns as outside the economy. Not anymore.

A few years back, I read Ved Mehta’s memoirs of his years at The New Yorker under editor William Shawn. Shawn helped Mehta find his first apartment: he actually scouted out a bunch of places with a real estate broker and wrote Mehta letters or called him about what he had seen. Shawn got Mehta set up with a meal service. The money was flowing. Again, not anymore.

The sea change isn’t just economic; it’s also cultural.

When we first started organizing graduate employees at Yale in the early 1990s, we got a lot of hostility. And nowhere more so than from the creative class. People in the elite media really disliked us. Many of them had left grad school or gone to fancy colleges, and we may have reminded them of the people they disliked when they were undergrads. (Truth be told: sometimes we reminded me of the people I disliked when I was an undergrad.) In any event, they saw us as pampered whiners, radical wannabees, Sandalistas in seminars. It was untrue and unfair. It didn’t matter. Liberals have their identity politics, too.

As some of you know, my union experience didn’t end happily. I lost three out of four of my dissertation advisers. And two of them wound up writing me blacklisting letters. After that, I wrote a mini-memoir-ish essay about the whole experience. I had great ambitions to be a personal/political essayist; this was my first stab at the genre. Part of my dissertation had been on McCarthyism and the blacklist, so I wove that into my essay: the experience of writing a dissertation that I wound up living a version of in real life.

I shopped it around to The New Yorker. I even called a top editor there after they turned it down. He answered the phone. That’s how things rolled back then. It was an awkward conversation.

I sent the essay to another top magazine. An editor there read and rejected it. I can’t remember if we spoke on the phone or corresponded by mail, but I remember his objection clearly. He didn’t like my comparison between my being blacklisted and McCarthyism. McCarthyism, he said, was about people going to jail; my essay was about people losing jobs and careers (which had happened to one of my fellow unionists, a student of the conservative classicist Donald Kagan).

The editor, of course, was wrong about that. Relatively few people went to jail under McCarthyism. Thousands upon thousands, however, lost their jobs and careers. That’s what McCarthyism was: political repression via employment. It didn’t matter. He knew what he knew.

Fifteen years later, there was a union drive at the magazine where this editor worked. He led it. He was fired.

My piece wasn’t great; it should have been rejected. I was an amateur, and it needed work. But I can’t help feeling that some part of the disconnect back then—the easy ignorance and confident incuriosity that so often pass in the media for common sense—had to do with where the creative class was in the 1990s: liberal on everything but unions.

Again, not anymore.

May 19, 2018

Conservatism and the free market

National Review just ran a review of my book, which Karl Rove tweeted out to his followers.

The review has some surprisingly nice things to say. It describes The Reactionary Mind as “well researched and brilliantly argued” and praises my “astonishingly wide reading…masterly rhetorical abilities…wizardry with the pen.” But on the whole the review is quite critical of the book. Which is fine. I’ve gotten worse.

But I couldn’t help noticing the appositeness of this.

Here’s the National Review on my book:

At no point in his book does Robin make any effort to account for the influence of Enlightenment-era classical liberalism on modern conservatism….[Adam] Smith’s influence on later conservatives is ignored.

And here’s Bill Buckley, the founder of National Review (and the modern conservative movement), to me, as quoted in my book:

The trouble with the emphasis in conservatism on the market is that it becomes rather boring. You hear it once, you master the idea. The notion of devoting your life to it is horrifying if only because it’s so repetitious. It’s like sex.

May 15, 2018

Chatting with Chris Hayes

Chris Hayes, the MSNBC anchor, has launched a new podcast Why Is This Happening? The idea is to go beneath the headlines, to take the long view, to examine current events against the long arc of history. I’m really thrilled that Chris chose me as his first guest. We talked about Trump, conservatism, and The Reactionary Mind. Have a listen!

dein goldenes Haar Margarete, dein aschenes Haar Sulamith

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers