Corey Robin's Blog, page 22

May 28, 2019

What Thomas’s opinion about abortion today tells us about his jurisprudence as a whole

I’ve been getting a lot of queries about Clarence Thomas’s concurring opinion in Box v. Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky. Briefly, Thomas spends all but a few paragraphs of his twenty-page opinion outlining what he sees as the eugenicist dimensions of abortion and birth control. This, as many have noted, is a new turn in Thomas’s abortion jurisprudence. Thomas essentially argues here that abortion is the way that women select and de-select the kinds of children they’re going to have.

What’s more, while much of the discussion on the right in this regard focuses on how considerations of the sex of the fetus or the presence of Down syndrome may influence the decision to have an abortion, Thomas focuses overwhelmingly on questions of race. Indeed, he spends an inordinate amount of time in his opinion rehearsing the role of racism in Margaret Sanger’s birth control movement. He discusses her work in Harlem and among African Americans in the South, as well as the connections between Nazism and eugenics. From there he goes to abortion. Reading Thomas, one comes away with the sense that abortion has nothing to do with the autonomy or equality of women but is instead a racist practice to control the size of the black population. The same goes for birth control.

At one point in the opinion, Thomas makes a point of noting the NAACP’s concerns during the 1960s about the racist dimensions of the birth control movement:

Some black groups saw “‘family planning’ as a euphemism for race genocide” and believed that “black people [were] taking the brunt of the ‘planning’” under Planned Parenthood’s “ghetto approach” to distributing its services. Dempsey, Dr. Guttmacher Is the Evangelist of Birth Control, N. Y. Times Magazine, Feb. 9, 1969, p. 82. “The Pittsburgh branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People,” for example, “criticized family planners as bent on trying to keep the Negro birth rate as low as possible.” Kaplan, Abortion and Sterilization Win Support of Planned Parenthood, N. Y. Times, Nov. 14, 1968, p. L50, col. 1.

At another point in his opinion, Thomas slyly mentions that the majority opinion in Roe v. Wade cites the work of an extraordinarily influential and renowned British legal scholar who, according to Thomas, flirted with eugenics:

Similarly, legal scholar Glanville Williams wrote that he was open to the possibility of eugenic infanticide, at least in some situations, explaining that “an eugenic killing by a mother, exactly paralleled by the bitch that kills her misshapen puppies, cannot confidently be pronounced immoral.” G. Williams, Sanctity of Life and the Criminal Law 20 (1957). The Court cited Williams’ book for a different proposition in Roe v. Wade, 410 U. S. 113, 130, n. 9 (1973).

By the time the opinion is over, it seems like abortion and birth control are simply a Nazi-style mode of racial management of the demographics of a population.

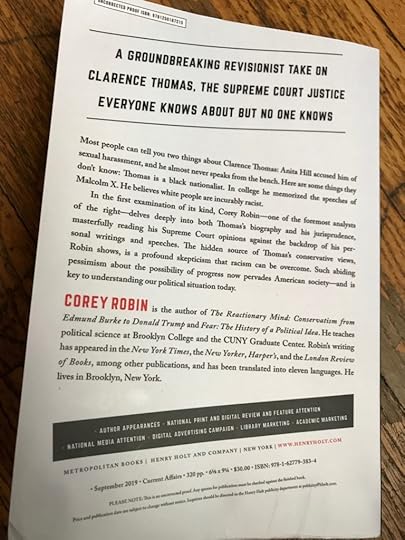

However extreme this opinion may be, it is very much in keeping with Thomas’s overall approach to constitutional questions. I have a book about Clarence Thomas, The Enigma of Clarence Thomas, coming out on September 24, and I don’t want to give too much of it away, so let me just say this: One of Thomas’s most consistent moves in his jurisprudence is to take constitutional matters that left and right disagree about but nevertheless argue about on similar terms—Thomas consistently takes these matters and transforms them into questions of race. He does this with the Establishment Clause: where both sides are debating questions of religion, he makes it all about race. He does the same with the Takings Clause: where both sides are debating questions of eminent domain, he makes it about race. He does this with campaign finance: where both sides are debating speech and the First Amendment, he makes it about race. In each instance, he takes the topic at hand and says, nope, this is really about race. And goes from there.

What’s more, as I show in the book, this isn’t just a ruse or a way of trolling the left. It’s not just a simple playing of the race card. It’s, well, you’ll have to read the book. Which, as I said, is out on September 24 and which you can pre-order now.

There’s also a lengthy footnote in Thomas’s opinion in Box, where he compares the thinking underlying eugenics to that which underlies disparate impact, a doctrine that falls under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. He cites the work of the conservative black economist Thomas Sowell. I think Thomas’s jurisprudence on disparate impact, as well as the impact and influence of Sowell upon Thomas, has been radically misunderstood. But again, I don’t want to give away too much of the book here. So…

Update (2 pm)

My wife Laura, who works in the reproductive rights movement, just made an excellent point about the parallel between Thomas’s opinion and the Anita Hill controversy. During the Senate confirmation hearings, when Hill accused Thomas of sexual harassment, there was a struggle in the commentary that boiled down to this question: Who gets to be black? Thomas and his supporters presented him as the embattled voice of the black community; Hill was depicted as a treacherous woman in alliance with liberal groups, trying to bring the black man—and with him, the black community—down. Thomas was black; Hill was a woman: that was the way the controversy played out, at least on one side. This was one of the many explosive insights at the heart of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s pioneering article “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.”

Fast-forward to Thomas’s opinion in Box v. Planned Parenthood. Studies show that black women are far more likely to get an abortion than other women. Support for abortion among black women is among the highest of any demographic group. And as Jamila Taylor argued, because black women are more likely to live in states with restrictive abortion laws, they have a lot more to lose from Thomas-inspired or Thomas-inflected opinions. So who gets to be black here? Once again, in Thomas’s world, it’s not black women; this time, it’s the fetus.

May 9, 2019

On Eric Hobsbawm and other matters

I’m in The New Yorker this morning, writing about Richard Evans’s new biography of the historian Eric Hobsbawm, explaining how the failures of Evans the biographer reveal the greatness of Hobsbawm the historian:

Hobsbawm’s biographer, Richard Evans, is one of Britain’s foremost historians and the author of a commanding trilogy on Nazi Germany. He knew Hobsbawm for many years, though “not intimately,” and was given unparalleled access to his public and private papers. It has not served either man well. More data dump than biography, “Eric Hobsbawm: A Life in History” is overwhelmed by trivia, such as the itineraries of Hobsbawm’s travels, extending back to his teen-age years, narrated to every last detail. The book is also undermined by errors: Barbara Ehrenreich is not a biographer of Rosa Luxemburg; Salvador Allende was not a Communist; one does not drive “up” from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles.* The biography is eight hundred pages because Hobsbawm “lived for a very long time,” Evans tells us, and he wanted “to let Eric tell his story as far as possible in his own words.” But, as we near the two hundredth page and Hobsbawm is barely out of university, it becomes clear that the problem is not Hobsbawm’s longevity or loquacity but the absence of discrimination on the part of his biographer.

Instead of incisive analyses of Hobsbawm’s books, read against the transformations of postwar politics and culture, Evans devotes pages to the haggling over contracts, royalties, translations, and sales. These choices are justified, in one instance, by a relevant nugget—after the Cold War, anti-Communist winds blowing out of Paris prevented Hobsbawm’s best-selling “The Age of Extremes” from entering the French market in translation—and rewarded, in another, by a gem: Hobsbawm wondering to his agent whether it’s “possible to publicize” “Age of Extremes,” which came out in 1994, “& publish extracts on INTERNET (international computer network).” Apart from these, Evans’s attentions to the publishing industry work mostly as homage to the Trollope adage “Take away from English authors their copyrights, and you would very soon also take away from England her authors.”

…

Hobsbawm was obsessed with boredom; his experience of it appears at least twenty-seven times in Evans’s biography. Were it not for Marx, Hobsbawm tells us, in a book of essays, he never would “have developed any special interest in history.” The subject was too dull. The British writer Adam Phillips describes boredom as “that state of suspended anticipation in which things are started and nothing begins.” More than a wish for excitement, boredom contains a longing for narrative, for engagement that warrants attention to the world.

A different biographer might have found in Hobsbawm’s boredom an opening onto an entire plane of the Communist experience. Marxism sought to render political desire as objective form, to make human intention a causal force in the world. Not since Machiavelli had political people thought so hard about the alignment of action and opportunity, about the disjuncture between public performance and private wish. Hobsbawm’s life and work are a case study in such questions. What we get from Evans, however, is boredom itself: a shapeless résumé of things starting and nothing beginning, the opposite of the storied life—in which “public events are part of the texture of our lives,” as Hobsbawm wrote, and “not merely markers”—that Hobsbawm sought to tell and wished to lead.

***

Down the corridor of every Marxist imagination lies a fear: that capitalism has conjured forces of such seeming sufficiency as to eclipse the need for capitalists to superintend it and the ability of revolutionaries to supersede it. “In bourgeois society capital is independent and has individuality,” “The Communist Manifesto” claims, “while the living person is dependent and has no individuality.” Throughout his life, Marx struggled mightily to ward off that vision. Hobsbawm did, too.

…

But what the Communist could not do in life the historian can do on the page. Across two centuries of the modern world, Hobsbawm projected a dramatic span that no historian has since managed to achieve. “We do need history,” Nietzsche wrote, “but quite differently from the jaded idlers in the garden of knowledge.” Hobsbawm gave us that history. Nietzsche hoped it might serve the cause of “life and action,” but for Hobsbawm it was the opposite: a sublimation of the political impulses that had been thwarted in life and remained unfulfilled by action. His defeats allowed him to see how men and women had struggled to make a purposive life in—and from—history.

The triumph was not Hobsbawm’s alone. Moving from politics to paper, he was aided by the medium of Marxism itself, to whose foundational texts we owe some of the most extraordinary characters of modern literature, from the “specter haunting Europe” to the resurrected Romans of the “Eighteenth Brumaire” and “our friend, Moneybags” of “Capital.” That Marx could find human drama in the impersonal—that “the concept of capital,” as he wrote in the “Grundrisse,” always “contains the capitalist”—reminds us what Hobsbawm, in his despair, forgot. Even when structures seem to have eclipsed all, silhouettes of human shape can be seen, working their way across the stage, making and unmaking their fate.

You can read it all here.

Also, as many of you know, for the last two years, I’ve been making the case that Donald Trump’s presidency is what the political scientist Steve Skowronek calls a “disjunctive” presidency. Over at Balkinization, I use the opportunity of my deep, deep agreement with the great Jack Balkin—whose views on so many things I share, and who also has argued for Trump as a disjunctive presidency—to raise some questions about our shared position, and where our analysis may go awry. You can read that here.

* Several astute readers pointed out to me that this locution of traveling “up” somewhere is often used in Britain to signify going from a smaller to a larger place rather than traveling from south to north. I passed the information on to my editor at The New Yorker, and they’ve now cut the phrase from the text. I’m leaving it here because, well, the error was mine, and in a passage where I’m pointing out Evans’s errors, I should acknowledge my own.

May 3, 2019

The Enigma of Clarence Thomas is coming to a theater near you!

I’ve finished my book on Clarence Thomas. The galleys are here; I love love love the cover! The pub date is September 24. You can pre-order now!

April 17, 2019

David Brion Davis, 1927-2019: Countersubversive at Yale

David Brion Davis, the pathbreaking Yale historian of slavery and emancipation, whose books revolutionized how we approach the American experience, has died. The obituaries have rightly discussed his many and manifold contributions, a legacy we will be parsing in the days and months ahead. Yet for those of us who were graduate students at Yale during the 1990s and who participated in the union drive there, the story of David Brion Davis is more complicated. Davis helped break the grade strike of 1995, in a manner so personal and peculiar, yet simultaneously emblematic, as not to be forgotten. Not long after the strike, I wrote at length about Davis’s actions in an essay called “Blacklisted and Blue: On Theory and Practice at Yale,” which later appeared in an anthology that was published in 2003. I’m excerpting the relevant part the essay below, but you can read it all of it here [pdf].

* * *

As soon as the graduate students voted to strike, the administration leaped to action, threatening students with blacklisting, loss of employment, and worse. Almost as quickly, the national academic community rallied to the union’s cause. A group of influential law professors at Harvard and elsewhere issued a statement condemning the “Administration’s invitation to individual professors to terrorize their advisees.” They warned the faculty that their actions would “teach a lesson of subservience to illegitimate authority that is the antithesis of what institutions like Yale purport to stand for.”

Eric Foner, a leading American historian at Columbia, spoke out against the administration’s measures in a personal letter to President Levin. “As a longtime friend of Yale,” Foner began, “I am extremely distressed by the impasse that seems to have developed between the administration and the graduate teaching assistants.” Of particular concern, he noted, was the “developing atmosphere of anger and fear” at Yale, “sparked by threats of reprisal directed against teaching assistants.” He then concluded:

I wonder if you are fully aware of the damage this dispute is doing to Yale’s reputation as a citadel of academic freedom and educational leadership. Surely, a university is more than a business corporation and ought to adopt a more enlightened approach to dealing with its employees than is currently the norm in the business world. And in an era when Israelis and Palestinians, Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Serbs, the British government and the IRA, have found it possible to engage in fruitful discussions after years of intransigent refusal to negotiate, it is difficult to understand why Yale’s administration cannot meet with representatives of the teaching assistants.

Foner’s letter played a critical role during the grad strike. The faculty took him seriously; his books on the Civil War and Reconstruction are required reading at Yale. But more important, Foner is a historian, and at the time, a particularly tense confrontation in the Yale history department was spinning out of control.

The incident involved teaching assistant Diana Paton, a British graduate student who was poised to write a dissertation on the transition in Jamaica from slavery to free labor, and historian David Brion Davis. A renowned scholar of slavery, Davis has written pathbreaking studies, earning him the Pulitzer Prize and a much-coveted slot as a frequent writer at the New York Review of Books. He represents the best traditions of humanistic learning, bringing to his work a moral sensitivity that few academics possess. Paton was his student and, that fall, his TA.

When Paton informed Davis that she intended to strike, he accused her of betraying him. Convinced that Davis would not support her academic career in the future—he had told her in an unrelated discussion a few weeks prior that he would never give his professional backing to any student who he believed had betrayed him—Paton nevertheless stood her ground. Davis reported her to the graduate school dean for disciplinary action and had his secretary instruct Paton not to appear at the final exam. In his letter to the dean, Davis wrote that Paton’s actions were “outrageous, irresponsible to the students…and totally disloyal.”

The day of the final, Paton showed up at the exam room. As she explains it, she wanted to demonstrate to Davis that she would not be intimidated by him, that she would not obey his orders. Davis, meanwhile, had learned of Paton’s plan to attend the exam and somehow concluded that she intended to steal the exams. So he had the door locked and two security guards stand beside it.

Though assertive, Paton is soft-spoken and reserved. She is also small. The thought of her rushing into the exam room, scooping up her students’ papers, engaging perhaps in a physical tussle with the delicate Davis, and then racing out the door—the whole idea is absurd. Yet Davis clearly believed it wasn’t absurd. What’s more, he convinced the administration that it wasn’t absurd, for it was the administration that had dispatched the security detail.

How this scenario could have been dreamed up by a historian with the nation’s most prestigious literary prizes under his belt—and with the full backing of one of the most renowned universities in the world—requires some explanation. Oddly enough, it is Davis himself who provides it.

Like something out of Hansel and Gretel, Davis left a set of clues, going back some forty years, to his paranoid behavior during the grade strike. In a pioneering 1960 article in the Mississippi Valley Historical Review, “Some Themes of Counter-Subversion: An Analysis of Anti-Masonic, Anti-Catholic, and Anti-Mormon Literature,” Davis set out to understand how dominant groups in nineteenth-century America were gripped by fears of disloyalty, treachery, subversion, and betrayal. Many Americans feared Catholics, Freemasons, and Mormons because, it was believed, they belonged to “a machine-like organization” that sought “to abolish free society” and “to overthrow divine principles of law and justice.” Members of these groups were dangerous because they professed an “unconditional loyalty to an autonomous body” like the pope. They took their marching orders from afar, and so were untrustworthy, duplicitous, and dangerous.

Davis was clearly disturbed by the authoritarian logic of the countersubversive, but that was in 1960 and he was writing about the nineteenth century. In 1995, confronting the rebellion of his own student, the logic made all the sense in the world. It didn’t matter that Paton was a longtime student of his, that she had many discussions with Davis about her academic work, and that he knew her well. As soon as she announced her commitment to the union’s course of action, she became a stranger, an alien marching on behalf of a foreign power.

Davis was hardly alone in voicing these concerns. Other respected members of the Yale faculty dipped into the same well of historical imagery. In January 1996, at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, several historians presented a motion to censure Yale for its retaliation against the striking TAs. During the debate on the motion, Nancy Cott—one of the foremost scholars of women’s history in the country who was on the Yale faculty at the time but has since gone on to Harvard—defended the administration, pointing out that the TA union was affiliated with the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union. Historians at the meeting say that Cott placed a special emphasis on the word “international.” The TAs, in other words, were carrying out the orders of union bosses in Washington. The graduate students did not care about their own colleagues, they were not loyal to their own. Not unlike the Masons and Catholics of old. It did not seem to faze Cott that she was speaking to an audience filled with labor historians, all of whom would have recognized these charges as classic antiunion rhetoric.

One of the reasons Cott embraced this vocabulary so unselfconsicously was that it was a virtual commonplace among the Yale faculty at the time. At a mid-December faculty meeting, which one professor compared to a Nuremberg rally, President Levin warned the faculty of the ties between the TAs and outside unions. The meeting was rife with lurid images of union heavies dictating how the faculty should run their classrooms. It never seemed to occur to these professors, who pride themselves on their independent judgment and intellectual perspicacity, that they were uncritically accepting some of the ugliest and most unfounded prejudices about unions, that they sounded more like the Jay Goulds and Andrew Carnegies of the late nineteenth century than the careful scholars and skeptical minds of the late twentieth. All they knew was their fear—that a conspiracy was afoot, that they were being forced to cede their authority to disagreeable powers outside of Yale.

Cott, Levin, and the rest of the faculty were also in the grip of a raging class anxiety, which English professor Annabel Patterson spelled out in a letter to the Modern Language Association. The TA union, Patterson wrote, “has always been a wing of Locals 34 and 35 [two other campus unions]…who draw their membership from the dining workers in colleges and other support staff.”

Why did Patterson single out cafeteria employees in her description of Locals 34 and 35? After all, these unions represent thousands of white- and blue-collar workers, everyone from skilled electricians and carpenters to research laboratory technicians, copy editors, and graphic designers. Perhaps it was that Patterson viewed dishwashers and plastic-gloved servers of institutional food as the most distasteful sector of the Yale workforce. Perhaps she thought that her audience would agree with her, and that a subtle appeal to their delicate, presumably shared, sensibilities would be enough to convince other professors that the TA union ought to be denied a role in the university.

The professor-student relationship was the critical link in a chain designed to keep dirty people out. What if the TAs and their friends in the dining halls decided that professors should wash the dishes and plumbers should teach the classes? Hadn’t that happened during the Cultural Revolution? Hadn’t the faculty themselves imagined such delightful utopias as young student radicals during the 1960s? Recognizing the TA union would only open Yale to a rougher, less refined element, and every professor, even the most liberal, had something at stake in keeping that element out.

In his article, Davis concluded with these sentences about the nineteenth-century countersubversive:

By focusing his attention on the imaginary threat of a secret conspiracy, he found an outlet for many irrational impulses, yet professed his loyalty to the ideals of equal rights and government by law. He paid lip service to the doctrine of laissez-faire individualism, but preached selfless dedication to a transcendent cause. The imposing threat of subversion justified a group loyalty and subordination of the individual that would otherwise have been unacceptable. In a rootless environment shaken by bewildering social change the nativist found unity and meaning by conspiring against imaginary conspiracies.

Though I don’t think Davis’s psychologizing holds much promise for understanding the Yale faculty’s response to the grade strike—the strike, after all, did pose a real threat to the faculty’s intuitions about both the place of graduate students in the university and the obligation of teachers; nor did the faculty seem, at least to me, to be on a desperate quest for meaning—he did manage to capture, long before the fact, the faculty’s fear that their tiered world of privileges and orders, so critical to the enterprise of civilization, was under assault. So did Davis envision the grotesque sense of fellowship that the faculty would derive from attacking their own students.

The faculty’s outsized rhetoric of loyalty and disloyalty, of intimacy (Dean [Richard] Brodhead called the parties to the conflict a “dysfunctional family”) betrayed, may have fit uneasily with their avowed professions of individualism and intellectual independence. But it did give them the opportunity to enjoy, at least for a moment, that strange euphoria—the thrilling release from dull routine, the delightful, newfound solidarity with fellow elites—that every reactionary from Edmund Burke to Augusto Pinochet has experienced upon confronting an organized challenge from below.

Paton’s relationship with Davis was ended. Luckily, she was able to find another advisor at Yale, Emilia Viotti da Costa, a Latin American historian who was also an expert on slavery. Da Costa, it turns out, had been a supporter of the student movement in Brazil some thirty years before and was persecuted by the military there. Forced to flee the country, she found in Yale a welcome refuge from repression.

March 26, 2019

Neoliberal Catastrophism

According to The Washington Post:

Former president Barack Obama gently warned a group of freshman House Democrats Monday evening about the costs associated with some liberal ideas popular in their ranks, encouraging members to look at price tags, according to people in the room.

Obama didn’t name specific policies. And to be sure, he encouraged the lawmakers — about half-dozen of whom worked in his own administration — to continue to pursue “bold” ideas as they shaped legislation during their first year in the House.

But some people in the room took his words as a cautionary note about Medicare-for-all and the Green New Deal, two liberal ideas popularized by a few of the more famous House freshmen, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.).

…

“He said we [as Democrats] shouldn’t be afraid of big, bold ideas — but also need to think in the nitty-gritty about how those big, bold ideas will work and how you pay for them,” said one person summarizing the former president’s remarks.

Obama’s words — rare advice from a leader who has shunned the spotlight since leaving office — come as the Democratic Party grapples with questions of how far left to lean in the run-up to 2020. Most Democratic candidates seeking the presidential nomination have embraced a single-payer health-care system and the Green New Deal, an ambitious plan to make the U.S. economy energy efficient in a decade.

It seems like there are an increasing number of areas where the discourse among centrists and liberals follows a fairly similar script. The opening statement is one of unbridled catastrophe: Trump is fascism on the ascendant march! Global warming will destroy us in the next x years! (I’m not making any judgments here about the truth of these claims, though for the record, I believe the second but not the first). The comes the followup statement, always curiously anodyne and small: Let’s nominate Klobuchar. How are you going to pay for a Green New Deal? Don’t alienate the moderates.

All of these specific moves can be rationalized or explained by reference to local factors and considerations, but they seem like part of a pattern, representing something bigger. Perhaps I’ve been reading too much Eric Hobsbawm for a piece I’m working on, but the pattern seems to reflect the reality of life after the Cold War, the end of any viable socialist alternative. For the last quarter-century, we’ve lived in a world, on the left, where the vision of catastrophe is strong, while the answering vision remains inevitably small: baby steps, cap and trade, pay as you go, and so on. Each of these moves might have its own practical justifications, but it’s hard to see how anyone could credibly conjure from those minuscule proposals a blueprint that could in any way be commensurate with the scale of the problem that’s just been mooted, whether it be Trump or climate change.

I wonder if there is any precedent for this in history. You’ve had ages of catastrophe before, where politicians and intellectuals imagined the deluge and either felt helpless before it or responded with the most cataclysmic and outlandish utopias or dystopias of their own. What seems different today is how the imagination of catastrophe is coupled with this bizarre confidence in moderation and perverse belief in the margin.

Neoliberal catastrophism?

March 25, 2019

Thoughts on Russiagate, Mueller, and Trump’s Prospects for Reelection

I find myself in a peculiar position with regard to the Mueller report (assuming—big assumption, I know—that we have a good enough sense at this point of what’s in it).

On the one hand, I was part of the Russiagate skeptic circle. I didn’t doubt that Russia had attempted to influence the election, but I didn’t think that attempt had much if any consequence; those who did, I thought, were grasping at straws. Nor did I think there was a strong case for the claim that Trump actively colluded with that effort and had thus put himself and the United States in hock to Putin. The evidence of all the active anti-Russian measures on the part of the US since Trump was elected was simply too great to lend those arguments too much credence. I also never believed, whatever the outcome of the report, that it would be the downfall of Trump or lead to his impeachment. I always took Nancy Pelosi at her word when she said, long before the midterms, that there would be no impeachment.

And like the other Russiagate skeptics, I found the constant breathless commentary, where each revelation was going to lead to the final end, where Trump was called a Russian asset (Lindsey Graham, too) grating in the extreme. And since I thought the attacks on the skeptics were nasty and often unfair, I can certainly understand why they’re now crowing; had I been as out in front or outspoken as they, I would be crowing, too.

But the bottom line is that I don’t feel disappointed or surprised by the outcome of the report—again, assuming (big assumption) we have a decent enough sense at this point of what is in the report—because I had fairly low expectations of it going in. If anything I feel relief that it’s over.

I always insisted that the investigation should proceed (and thought the fear that it was going to be shut down prematurely to be vastly overblown) and that it was good that it was happening because there was clearly enough evidence of impropriety and illegality for it to go forward. I thought it was good to get to the bottom of things, and the evidence of corruption that it has turned up seems like, maybe, a useful roadmap going forward for thinking about political power and oligarchy. And as others have pointed out, it shows the double standards of our justice system, where the poor are punished and the rich and powerful get off fairly easily. But I always thought the vision of Trump humiliated by Mueller and then impeachment were, like the idea of Putin’s puppet or a stolen election, completely fanciful.

On the other hand, unlike many in the Russiagate skeptic circle, I don’t think the Mueller report really changes much of anything in terms of the political situation we’re in. I don’t think Trump is going to get some big boost from this, as a lot of lefties seem to think. The fact is, the Democrats, on the ground, have been—very wisely, I might add—focusing on the economy, voting rights, racism and anti-immigrant nativism. They have not been pushing Russia as an electoral question. This has always been a media and social media obsession; for once in their lives, most Democrats, on the ground, have made the rational political calculation.

So where does that leave us? Pretty much where we’ve always been. If you hoped Mueller and Russia would be the downfall of Trump and are now crestfallen, I’d say you really have no reason to feel upset. What will bring Trump down will be what was always going to bring down Trump: his failure to deliver enough to the party’s voters, the growing incoherence and unsettlement on the right about what its basic project is all about, and the rising organization of the left.

So it’s back to our regularly scheduled programming. Hopefully, with less distraction and fewer fantasies of happy endings.

March 4, 2019

Do You Believe in Life After Hayek

Sorry about the title; advertisements for The Cher Show are all over New York these days, so the song is in my head. Anyway…

In the Boston Review, the left economists Suresh Naidu, Dani Rodrick, and Gabriel Zucman offer an excellent manifesto of sorts for a new progressive economic agenda. I was asked to respond, and in a move that surprised me, I wound up returning to Hayek to see what we on the left might learn from him and his achievement. Here’s a snippet:

Far from resting neoliberalism on the authority of the natural sciences or mathematics (forms of inquiry Hayek and Mises sought to distance their work from) or on the technical knowledge of economists (as Naidu and his co-authors claim), Hayek recognized that the argument for capitalism had to be won on moral and political grounds through the political arts of persuasion.

Here’s where things get interesting. Though Hayek famously abandoned formal economics for social theory after the 1930s, his social theory remained dedicated to elaborating what he saw as the essential problem of economics: how to allocate finite resources between different purposes when society cannot agree on its most basic ends. With its emphasis on the irreconcilability of our moral ends—the fact that members of a modern society do not and cannot agree on a scale of values— Hayek’s point was fundamentally political, the sort of insight that has agitated everyone from Thomas Hobbes to John Rawls and Jürgen Habermas. Hayek was unique, however, in arguing that the political point was best addressed, indeed could only be addressed, in the realm of the economic. No other discourse—not moral philosophy, political theory, psychology, or theology—understood so well that our ultimate moral values and political purposes get expressed to others and revealed to ourselves only under conditions of radical economic constraint—when one is forced to assign a limited set of resources to different ends, ends that favor different sectors of society.

Morals are not really morals if they are not material, Hayek believed. Outside the constraining circumstance of the economy, our moral claims are so much wind. Inside the economy, they assume force and depth, achieving a revelatory clarity and profundity….

The intrinsic links between moral and economic life as well as the intractability of moral conflict, the incommensurability of our moral views, were the kernels of insight that animated Hayek’s most far-reaching writing against socialism. The socialist presumes an agreement on ultimate ends: the putatively shared understanding of principles such as justice or equality is supposed to make it possible for state planners to conceive of their task as technical, as the neutral application of an agreed upon rule. But no such agreement exists, Hayek insisted, and if it is presumed to exist, nothing will reveal its non-existence more quickly than the attempt to implement it in practice, in the distribution of finite resources toward whatever end has been agreed upon.

…

Hayek translated moral and political problems into an economic idiom. What we need now, I would argue, is a way to uninstall or reverse that translation.

In the rest of the piece, I briefly (very briefly) sketch out, with the help of Polanyi, what that might mean. This is something I hope to be developing further in an article I’m writing with Alex Gourevitch on socialist freedom. But in the meantime, here’s the Boston Review piece in full.

Marshall Steinbaum and Alice Evans also have excellent responses.

March 1, 2019

Interview about the Historovox with Bob Garfield of On the Media

My piece on the Historovox has provoked a lot of controversy and pushback. Dan Drezner devoted a column to it in The Washington Post. Others have weighed in on social media. I had a chance to talk with Bob Garfield of the NPR show On the Media about the piece. Have a listen.

February 28, 2019

I was the target of a private Israeli intelligence firm, and all I got was this lousy t-shirt

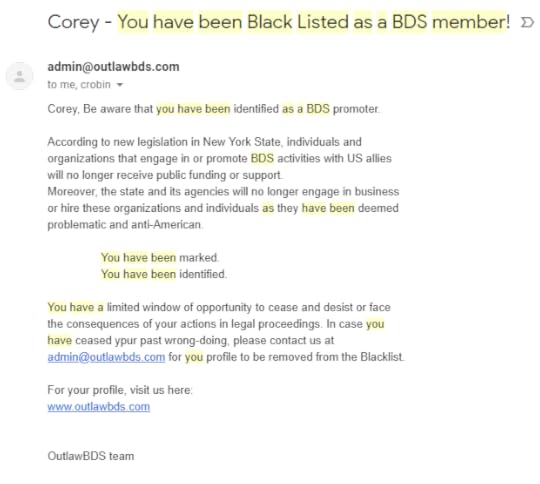

In September 2017, I got a “cease and desist” email from an organization called outlawbds. They informed me that because of my activism around BDS, I had been put on a “blacklist”—yes, they used that word, twice—and that I had a limited window of time to change my tune on BDS in order to get my name removed from the blacklist and avoid the legal consequences of my advocacy. “You have been marked,” the email warned me. “You have been identified.”

Turns out the whole thing was part of an operation of an Israeli intelligence firm called “Psy-Group.” Whose activities have now been exposed in The New Yorker.

Here are just a snippet of the items that might be of interest to those of us on CUNY campuses and in the New York area.

The campaign, code-named Project Butterfly, initially targeted B.D.S. activists on college campuses in “a single U.S. state,” which former Psy-Group employees have told me was New York. The company said that its operatives drew up lists of individuals and organizations to target. The operatives then gathered derogatory information on them from social media and the “deep” Web, areas of the Internet that are not indexed by search engines such as Google. In some cases, Psy-Group operatives conducted on-the-ground covert human-intelligence, or HUMINT, operations against their targets. Israeli intelligence officials insist that they do not spy on Americans, a claim that is disputed by their U.S. counterparts. Israeli officials said, however, that this prohibition does not apply to private companies such as Psy-Group, which use discharged Israel Defense Forces soldiers and former members of elite intelligence units, rather than active-duty members, in operations targeting Americans.

You can read more here.

And here’s the email I got.

February 20, 2019

The Historovox Complex

I’ve got a new gig at New York Magazine, where I’ll be a regular contributor, writing on politics and other matters. Here, in my first post, I tackle “the Historovox” (my wife Laura came up with the phrase), that complex of journalism and academic research that we increasingly see at places like Vox, FiveThirtyEight, and elsewhere. Long story, short: while I firmly believe in academics writing for the public sphere, there are better and worse ways to do it.

Here are some excerpts:

There’s a bad synergy at work in the Historovox — as I call this complex of scholars and journalists — between the short-termism of the news cycle and the longue durée-ism of the academy. Short-term interests and partisan concerns still drive reporting and commentary. But where the day’s news once would have been narrated as a series of events, the Historovox brings together those events in a pseudo-academic frame that treats them as symptoms of deeper patterns and long-term developments. Unconstrained by the protocols of academe or journalism, but drawing on the authority of the first for the sake of the second, the Historovox skims histories of the New Deal or rifles through abstracts of meta-analysis found in JSTOR to push whatever the latest line happens to be.

When academic knowledge is on tap for the media, the result is not a fusion of the best of academia and the best of journalism but the worst of both worlds. On the one hand, we get the whiplash of superficial commentary: For two years, America was on the verge of authoritarianism; now it’s not. On the other hand, we get the determinism that haunts so much academic knowledge. When the contingencies of a day’s news cycle are overlaid with the laws of social science or whatever ancient formation is trending in the precincts of academic historiography, the political world can come to seem more static than it is. Toss in the partisan agendas of the media and academia, and the effects are as dizzying as they are deadening: a news cycle that’s said to reflect the universal laws of the political universe where the laws of the political universe change with every news cycle.

…

The job of the scholar is not to offer her expertise to fit the needs of the pundit class. It’s to call those needs into question, not to provide different answers to the same questions but to raise the questions that aren’t being asked.

Everyone knows and cites Orwell’s famous adage: “To see what is front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” Less cited is what follows: “One thing that helps toward it is to keep a diary, or, at any rate, to keep some kind of record of one’s opinions about important events. Otherwise, when some particularly absurd belief is exploded by events, one may simply forget that one ever held it.” To see what’s right in front of one’s nose doesn’t mean seeing without ideology. It means keeping track of how we think and have thought about things, being mindful of what was once on the table and what has disappeared from view. It means avoiding the gods of the present.

The job of the scholar, in other words, is to resist the tyranny of the now. That requires something different than knowledge of the past; indeed, historians have proven all too useful to the Historovox, which is constantly looking for academic warrants to say what its denizens always and already believe. No, the job of the scholar is to recall and retrieve what the Marxist critic Walter Benjamin described as “every image of the past that is not recognized by the present.” The task is not to provide useful knowledge to the present; it is to insist on, to keep a record of, the most seemingly useless counter-knowledge from the past — for the sake of an as-yet-to-be imagined future.

The whole thing is here.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers