Corey Robin's Blog, page 18

July 1, 2023

Markets and Speech: Where Does the Public Reside?

If you were to do an informal poll of conventional progressive opinion—asking where is the public to be found, in acts of speech or in the marketplace—I suspect most liberals, and probably not a few leftists, would say: in acts of speech.

Since the eighteenth century, speech has been firmly associated with the public sphere or the public square. “The people’s darling privilege”: that’s how freedom of speech was understood, as the instrument of the people, assembled in their sovereign and public capacity. There’s a long history behind the notion, stretching back to Aristotle, whose justification for the claim that man is a political animal rests upon the fact that human beings, unlike other animals, have the capacity for speech. In the twentieth century, Hannah Arendt argued that our politicalness was to be found in our capacity for word and deed. Speech and politics, speech and the public, speech and the people: Long before constitutional lawyers thought of rights as primarily individual claims, they thought of freedom of speech as something that belonged to, and required, a public square. Freedom of speech was less something that belonged to the individual than it was a property of good public life.

Markets, on the other hand, have a more checkered status in the contemporary progressive imagination. Returning, again, to our hypothetical poll of liberal and left opinion, I suspect many progressives associate the market, first and foremost, with private acts of possession: the ownership of property, ownership of the means of production, personal possession of money, and so forth. Though all of these elements—property, money, production—involve the state, indeed are inconceivable without some public entity of acknowledgment and enforcement, they are not thought to be public, of the people, in the same way as speech. In fact, we often think of the market as involving individuals, and even when we think of social classes or groups in the market, the idea is that they are pursuing their own particular, non-public, interests. From the point of view of some parts of the left, that is one of the problems of the market: its privatizing or individualizing effect.

Which leads me to 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, yesterday’s Supreme Court case that pitted the First Amendment rights of a graphic designer against the anti-discrimination claims of LGBTQ individuals. Contrary to popular myth, the rights at stake here do not involve religion. Lorie Smith, the designer looking to go into the website business for weddings, was claiming that her free speech rights were threatened by Colorado’s anti-discrimination law, which prohibits public accommodations, including public-facing private businesses, from denying goods and services to individuals on the basis of those individuals’ sexual orientation (and race, creed, religion, etc.)

How was Smith’s freedom of speech at stake, you ask? Smith claimed that because she doesn’t believe in gay marriage, the state’s requirement forces her, compels her, to utter words that she does not believe. A website is a combination of text and graphics. It would be, in this case, custom-designed for the individual couple in question. To design a website celebrating a gay couple’s union would be the equivalent of forcing a Muslim filmmaker—the Court kept returning to this analogy—to make a movie with a Zionist viewpoint. (I’m just the messenger here; not endorsing the claim. Or the assumption about Muslims behind the analogy.)

What’s interesting about the case is how it reverses the left’s usual assumptions about speech and markets. If you read Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent, which was joined by the Court’s liberals, it’s clear that while she does not deny that Smith’s website design involves speech, that it is expressive and communicative, she nevertheless insists upon putting Smith’s actions in the context of the market. Not because Smith would make money from her web design but because, by virtue of entering the market, she has opened her business—including her business’s expressive activities—to the public. By entering the market, she has to accept the rules of the market, one of which is to provide access to any and all members of the public. One might say that the market is a kind of public.

Sotomayor traces this principle back to a 1701 case in English common law, but it also animates much of the Enlightenment’s thinking about commerce and markets. Adam Smith, like David Hume and many other theorists of commercial society, thought that an increasingly widened commerce would draw us all out of our local and parochial attachments, connecting us to ever broader and more distant parts of the world. One can easily find the trace of his and other eighteenth-century thinkers’ positions in the Interstate Commerce Clause of the Constitution and in some of the great civil rights cases of the twentieth century, which involve institutions like inns and hotels and restaurants—not just places of commerce and the market, but places of commerce that are connected with travel, with encounters between strangers, with the growing relationships between peoples from distant places and lands. The market connects us, in this tradition, so if we enter the market, we have to connect.

Now we come to Neil Gorsuch, who wrote the opinion for the Court’s conservative majority. For Gorsuch, and for his fellow conservatives, the market barely makes an appearance in this case. Instead, he and the conservatives take the side of Smith, not Adam Smith, but Lorie Smith, the anti-gay marriage website designer. What is at stake are not her rights in the market, which, as Sotomayor relentlessly observers, would open, even force, Smith the designer, into the hands of the public. Instead, says Gorsuch, it is her rights of speech, which Gorsuch and the conservatives see as belonging to the sphere of conscience, of Smith’s inner beliefs. In the same way that the state cannot force me to take an oath to avow a belief I do not hold, to utter words that I do not think, so should the state not force Smith’s business to avow beliefs that she does not hold. That she has entered the market to express herself is neither here nor there, to Gorsuch. Her beliefs, her words, are hers. She may be in the market, but that doesn’t mean she has to connect. Her speech protects her from connecting. It protects her from the public.

So there we have it. Obviously there are all kinds of politics and interests going on here, which have little to do with the formal statements that are being articulated in these warring Court opinions. But the statements matter, and should get us to think some more about our own assumptions regarding where the public lies: in our speech acts or in our market life.

Additionally, there’s an assumption, particularly on the left, that what the right has pursued, through neoliberalism, is the relentlessly economistic organization of society. Everything should be subjected to the rule of the market. Yet as 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis demonstrates, that’s not quite true. It’s not simply that the right wishes to uphold the right to discriminate against LGBTQ people, though that is true. It’s also that the neoliberal right does its work not simply by economizing the public sphere but also by refusing to see, sometimes, the economic dimensions of the public sphere, preferring to see those dimensions as speech acts, expressive, communicative rather than commercial. Conversely, the left, sometimes, can do its best work not by denying the economic dimensions of the public sphere, not by relegating market relations to a second-order sphere of private property and possession, but by seeing the public dimension of market relations and insisting on their connective tissue, the ways in which the market brings us together and creates a public, however imperfect and deformed.

If you want to read more about these issues, take a look at my article on Adam Smith and chapter six of my book on Clarence Thomas. I’ll also be pursuing these issues in my next book, King Capital.

June 3, 2023

June is the Cruelest Month

June is Supreme Court month, when Clarence Thomas gets to hand down one edict after another. As an antidote, my publisher is offering The Enigma of Clarence Thomas on sale! You can get the Kindle version for the low price of $2.99. Buy it now!

May 23, 2023

We’re slowly moving past the clichés of Clarence Thomas

If you haven’t been following all the Clarence Thomas news, I’ve been talking with a lot of media outlets about him, the corruption scandal, how it fits with his larger life story, and where things are headed with Thomas and the Court. At the bottom of this post is a roundup of all the interviews and programs and pieces I’ve been involved in.

Aside from tooting my own, I’ve for a reason for listing all my media appearances about Thomas. As you’ve probably noticed, there has been a demonstrable uptick in interest about Thomas—and his Black nationalist origins—since last year. It began with his infamous concurrence in the Dobbs decision, which I wrote about at The New Yorker, and it hasn’t let up since then. The latest corruption scandal is, to my mind, a continuation of the newfound interest in Thomas.

The question is: What explains this interest? For years, Thomas was ignored, dismissed as the judge who never speaks, the judge who doesn’t think for himself or write his own opinions, the judge who isn’t smart. The only question I ever got from people was: Why doesn’t he ask questions from the bench? Then, with Trump’s appointment of three right-wing judges to the Court, and the Court’s dramatic shift to the right, people began to recognize that Thomas has a lot of power. It’s not the John Roberts Court; it’s the Clarence Thomas Court.

We no longer hear much about that silent Thomas, the stupid Thomas, or Scalia’s puppet. Instead, it’s the corrupt Thomas, the con man Thomas, which, say what you will about those epithets, none of them treat him as stupid. All of those epithets—some of which are totally fair (Thomas does get a lot of unsavory gift from very rich men), some of which are not fair at all (that he’s con man)—show that people are now reckoning with the most salient fact about Clarence Thomas, which is that he’s powerful.

But those epithets still try to evade another salient fact about Thomas: that he has a well developed jurisprudence that reflects his deep philosophy about race, wealth, and the Constitution. Harlan Crow didn’t create that jurisprudence; Clarence Thomas did.

What I really appreciate about all the shows I list below is that they are made by journalists who are trying to get beyond the easy stories and lazy stereotypes about Thomas. Thomas is powerful and he is corrupt—and he also has a well developed, constitutional vision of Black people in America and their relationship to wealth and power. Those elements of his persona may be in tension, they may make for contradictions, but they cannot be captured or understood by clichés and slogans.

So read or listen to these stories and shows I mention below, and see what you think.

On Sunday, I joined the NPR show, Notes from America with Kai Wright, to talk about “Clarence Thomas and his Hotep Supreme Court.” I first heard the term “hotep” applied to Thomas in Twitter conversations with Tressie McMillan Cottom, and as soon she made the connection to me, it all made sense. I was happy to hear Kai Wright pick up on it in our conversation, and that it’s in the title of the episode. Our local NPR station in New York, WNYC, is currently featuring the show as its “top story” on the website, and it has a great description of my thesis on Thomas: “Justice Thomas is a Black nationalist — but that doesn’t mean he loves all Black people. We unearth his ideological roots and what they mean for the Court’s looming opinions.” Anyway, have a listen to the show here.

Last week, the wonderful NPR podcast series More Perfect aired a lengthy episode on Thomas, which has been in the works for more than a year, and which they called “Clarence X.” That Clarence X is a reference to an article that a former Thomas Clerk, Stephen Smith, wrote about the influence of Malcolm X and Black nationalism on Thomas—and as the More Perfect producers found out, when Smith sent Thomas the article, Thomas wrote back an appreciative reply, which he signed “Clarence X.” The producers also discovered that Ginni Thomas has apparently sent out irate emails about my book to a listserv of Thomas clerks, “railing about how this Marxist professor thinks he understands her husband better than she does.” The whole podcast is filled with tidbits like these and voices like Juan Williams, who, more than any other journalist, put Clarence Thomas’s name on the map back in 1980, and Angela Onwuachi-Willig, the Dean of Boston University law school, who was one of the early legal scholars to notice Thomas’s Black nationalist roots and their influence on his jurisprudence. I loved working with Julia Longoria, the host of the show, and the entire team of producers and editors and researchers, who were absolutely dedicated to getting the full story on Thomas. The episode is a triumph of narrative journalism.

Last month, I talked with Brooke Gladstone of NPR’s On the Media, and we dove deep into Thomas’s views on money and rich men, and how those views have structured his approach to the First Amendment (on campaign finance and commercial speech) and help us understand this latest corruption scandal.

I also talked to Briahna Joy Gray on her Bad Faith podcast, where we discussed how Thomas shows that the real culture war between left and right is about money.

Finally, I wrote up some of my thoughts on the Clarence Thomas scandal in Politico.

And there’s one more big show coming out on Thomas in the coming weeks; I’ll keep you posted.

May 22, 2023

A Watergate for Our Time

If you haven’t caught an episode of “White House Plumbers,” the new HBO series on Watergate, I highly recommend it.

For people my age, Watergate will always be connected to All the President’s Men, not the book by Woodward and Bernstein but Alan J. Pakula’s 1976 film. I can’t think of Ben Bradlee without thinking of Jason Robards, Deepthroat without Hal Holbrook, or Hugh Sloan without Meredith Baxter Bierney, who played Sloan’s wife in the film.

The point of the film, and those actors, was to supply a sense of gravitas to a country stricken by the sordidness of the affair. No matter how criminal Nixon may have been, his criminality was redeemed by the feel of the film, with its spirit of agonized conscience and liberal reckoning. That feel derived from the piety and passion of the Cold War, making it the perfect film for, and of, the Cold War state.*

We no longer live in the shadow of the Cold War. We no longer live in the shadow of 9/11. Both of those moments elicited a sense that something had to be done, that something could be done. We no longer live in those countries. We live in a country that exudes a sense that nothing can be done. Debt ceiling crisis? The Supreme Court will say no. Diane Feinstein’s refusing to retire and gumming up the works of judicial appointments? It’s her choice. Climate change? What are you going to do?

White House Plumbers is the story of Watergate told from the perspective of our own failed state. The series isn’t the story one attempted break-in at the Watergate hotel; it’s the story of four bungled attempts at a break-in. Gordon Liddy is no longer a scary ideological fanatic, as he was in All the President’s Men, burning his hand over a candle to prove how tough and committed he was. He’s now a dorky bumbler whose hand over the candle trick grosses out the prostitutes he’s trying to impress. Howard Hunt frets over country clubs and career. Both men come off as wannabe entrepreneurs who pitch the break-in at the hotel as if they were making bids for a contract with an aging nonprofit.

White House Plumbers is the story of a country whose time is past, of geriatric grifters who talk tough and trip over their shoelaces. It’s the Watergate for our time, the Watergate that forces us to see ourselves for who we are.

* My daughter, with whom I’ve been watching “White House Plumbers,” found this 1973 article in the New York Times by R.W. Apple, the dean of the White House press corps, about H.R. Haldeman, Nixon’s Chief of Staff. Headlined “Haldeman the fierce, Haldeman the faithful, Haldeman the fallen,” the article said, “Haldeman made himself into a latter‐day Janus, a guardian of the gateway to President Richard M. Nixon, a god of the going and the coming.” That gives you a sense of the exalted terms in which this extended experiment in criminality was described by the Washington media.

April 22, 2023

Talking Clarence Thomas and Money with NPR’s Brooke Gladstone

I talked about the Clarence Thomas scandal with Brooke Gladstone on On the Media this weekend. You should be able to hear it on any NPR outlet wherever you are, but in case you miss it, here’s a link where you can catch it.

April 18, 2023

The real problem of Clarence Thomas

I’ve got a piece up at Politico this morning, setting out what I think the real Clarence Thomas scandal is, why corruption may not be the best way to think about it, and what the proper approach of the Left should be to the problem of Clarence Thomas:

As a description of the problem of Clarence Thomas, however, corruption too has its limits. Morally, corruption rotates on the same axis as sincerity — forever testing the purity or impurity, the tainted genealogy, of someone’s beliefs. But money hasn’t paved the way to Thomas’ positions. On the contrary, Thomas’ positions have paved the way for money. A close look at his jurisprudence makes clear that Thomas is openly, proudly committed to helping people like Crow use their wealth to exercise power. That’s not just the problem of Clarence Thomas. It’s the problem of the court and contemporary America….

Money “is a kind of poetry,” wrote Wallace Stevens. Thomas agrees. More than an aid to speech or speech in the metaphorical sense, money is speech. Not only do our donations to campaigns and candidates “generate essential political speech,” Thomas writes in a 2000 dissent, but we also “speak through contributions” to those campaigns and candidates. He’s not wrong. When my wife and I gave money to the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, we were doing more than aiding their candidacies. We were voicing our political values and advocating our policy preferences, just as we did when we showed up at their rallies and canvassed for them, door to door…

If money is speech, the implication for democracy is clear. There can be no democracy in the political sphere unless there is equality in the economic sphere. That is the real lesson of Clarence Thomas.

You can read the whole piece here, at Politico. And then, if you haven’t yet bought The Enigma of Clarence Thomas, which forms the basis for the piece, buy the book!

Update: I spoke with Forbes Magazine about the Clarence Thomas story. The interviewer is Diane Brady, who wrote one of the best books on Thomas, actually a group biography of Thomas and his Black classmates at Holy Cross. It was a delight to talk with her.

April 13, 2023

The real culture war between the left and the right is about money: On the Clarence Thomas scandal

Briahna Joy Gray, who is one of my favorite podcasters and interviewers, and I went deep into the Clarence Thomas scandal. I trace his actions back to an obscure speech he delivered to a libertarian outfit in San Francisco in 1987, where he set out his basic agenda and philosophy: “The real culture between the left and the right is about money.”

You can watch it here on YouTube.

March 29, 2023

Talking fascism, the Constitution, and history with Jamelle Bouie

Last week, as I was losing my voice, I had a really fascinating conversation with Jamelle Bouie of the New York Times, moderated by Katrina vanden Heuvel of The Nation, about the state of American democracy. You can watch it here. It was a wide-ranging discussion: we talked about whether fascism is a good model for understanding the contemporary American right, the helps and hindrances of the Constitution, the virtues and vices of returning to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for insights into current events, and more. Bouie is one of those rare political writers who really knows his history; it’s almost never that I read one of his Times columns without learning something I didn’t know about the American past. I strongly encourage you to read his work at the Times, and enjoy watching this video of our conversation. And apologies for my voice: my wife said I sounded like Brenda Vaccaro.

March 9, 2023

King Capital

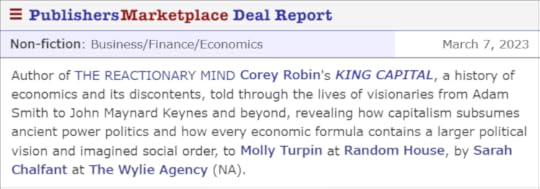

I’ve been wanting to shout this from the rooftops, and now I can. I’ve just signed a contract for my next book, which is called King Capital, with Random House, where I’ll be working with Molly Turpin, who edited one of my favorite books of the last decade. After floundering around for a few years, with one false start after another, I’m thrilled to be writing this book and working with Molly. I feel more than lucky that Sarah Chalfant (The Wylie Agency), who did so much for this shidduch, is my agent.

Now to write the book. In the meantime here’s a brief article on the sale, which was reported in yesterday’s Publishers Marketplace.

December 4, 2022

Jane Austen on the Post Office and State Capacity

“The post-office is a wonderful establishment!” said she.—”The regularity and dispatch of it! If one thinks of all that it has to do, and all that it does so well, it is really astonishing!”

“It is certainly very well regulated.”

“So seldom that any negligence or blunder appears! So seldom that a letter among the thousands that are constantly passing about the kingdom, is even carried wrong—and not one in a million, I supposed, actually lost! And when one considers the variety of hands, and of bad hands too, that are to be deciphered, it increases the wonder!

“The clerks grow expert from habit.—They must begin with some quickness of sight and hand, and exercise improves them. If you want any further explanation,” continued he, smiling, “they are paid for it. That is the key to a great deal of capacity. The public pays and must be served well.”

—Jane Fairfax talking with John Knightley in Emma

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers