Rick Bailey's Blog: Stuff happens, then you write about it, page 13

April 9, 2023

Milk, Please

No one, as far as I can tell, drinks milk in Italy.

Whenever I find myself standing in line at the supermarket, holding a liter of milk–latte parzialmente scremato, which I take to be fresh 2 percent–I’m the only one. I’ve never seen anyone buy milk. There’s a tiny little milk section over there in the dairy aisle, along with a variety of yogurts and butters and a gazillion different wet and semi-wet fresh cheeses. Not a lot of milk. And like gasoline, milk is sold by the liter, not by the gallon. (A gallon!) Some days there’s no fresh milk on the shelf at all. Unthinkable. Across from the cooler are cases of UHT milk. No need to refrigerate that milk. Store it in the closet, it lasts forever. And tastes terrible.

I don’t think the woman behind me in line, or the cashier once I get there, looks at me and thinks, Aw, this grandpa must be buying it for a grandchild at home. And I certainly don’t think they assume I’m going to drink it. They probably just think, He must be an American. Then I open my mouth and remove all doubt.

In hotel breakfasts in Italy you find little spoon-size packets of Nutella. On hard crust bread or on a slice of prepackaged crispy junior white bread they call toast, Nutella is a treat. For American guests, and for Europeans who supposedly like a morning comestible called mueslix (never seen it), you’ll find fresh milk. In 45 years of travel over there, I have never seen a European eat cereal of any kind. I always have some, and feel, I confess, conspicuously American and, frankly, quite juvenile in my tastes as I pour milk over my Raisin Bran and granola. (I draw the line at Fruit Loops.) I also pour a glass of milk to enjoy with bread and nutella.

When we get back to the US, one of the first things I eat is a piece of toast and peanut butter, with a glass of milk.

If you looked in our fridge, you’d think that we have a habit, that one or both of us is a milk-aholic. That we should seek help. My son-in-law looked in there once, after I had just come home from Costco, and said Wow, who drinks all that milk? Well, I do. Drinking it takes a while. Ultra pasteurized milk today will last up to a month in the fridge. Confession: it’s gone before a month is up.

Supposedly milk isn’t good for you. My brother, raised at the same kitchen table I was, quit milk a long time ago. As kids we drank milk with every meal. So did our father. I don’t do that anymore, but I don’t want a glass of water with a piece of toast and peanut butter.

Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine states, “Milk and other dairy products are the top source of saturated fat in the American diet, contributing to heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. Studies have also linked dairy to an increased risk of breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers.” Gee, I don’t want any of those things. But it’s not like I drink milk every day, I don’t skulk down in the basement or out to the garage and sneak a snort of milk to calm my nerves, I don’t keep a pint of it under the seat in the car, I don’t binge drink milk or go on a milk bender for days at a time. I’ve got things under control, I tell myself.

Google finds 179 slogans and taglines to sell milk. Some examples: It’s a natural (gently argumentative). It does a body good (playing the health card). Cows in wide pastures produce better tasting milk (appealing to the ethical consumer). Vast fields, make happier cows, and better tasting milk (bad punctuation). Experience the cream of the crop (oh, please). Creamy, dreamy dairy (poetry in a glass).

I like it. That’s all there is to it. Milk, please.

April 2, 2023

Ferlinghetti in Grottamare

Yesterday was a terrific day.

Once again Tizi and I were brought to a beautiful place by her cousin Arnoldo and his amazing wife Marisa. It was a visit to Grottamare and, close by, to Massignano,

where, with their garden club, a group of generous and friendly souls, we toured a citrus grove, a horticultural and architectural treasure dating back centuries, which is now being restored.

After the tour and wine tasting at the Iacopini estate, we drove into Grottamare. We had lunch next to the sea, then drove to the upper town and walked. It was a sunny day. The gods smiled upon us.

What I didn’t anticipate was discovering that Lawrence Ferlinghetti passed through and stopped in Grottamare, waylaid by a problem on the train. He is remembered by the town and celebrated for the poem he wrote. There it was, the poem on a plaque, and some guy standing in front of it telling us where the restaurant was.

Ferlinghetti captures the beauty and aura of the Grottamare. Photos hardly do it justice. The poem succeeds.

Turquoise sea off Grottamare,

Grottamare with its sea caves

echoing

along the Adriatic.

Echo of siren song

still reaches me

inside the silent train

once more the lost voices calling

undersea

Ah, but naturally

all is illusion

the fog still lies heavily

in the olive trees

Dawn is made by the clock

and not by light

which only exists in our minds

men and women sleep

in their usual darkness

Only the light

asleep in their eyes

gives any hint

of the iridescent future

of an incandescent destiny

Only far off

beyond the far islands

the sea sends back

its turquoise answer

March 28, 2023

Exceeding Your Limit

This week I’ve had a few occasions to reflect on the concept of risk. Earthquake, tornado, air travel, rental car.

Thursday Tizi and I went to the Bologna airport to pick up a car. At the rental car booth it always takes a while. There are documents to present, long phone calls to make (by the car rental rep, to whom I don’t know), explanations and payments, initialing and signing. This day when the guy at the Drivalia desk finally hands me the paperwork and the car key, he says, in English for my benefit, “It’s a Soobe.”

“A what?”

“Soobe,” he says again.

“You mean, like, Subaru?” What do I know.

He shakes his head, probably thinking, Why try? Moron.

I mean me moron. He realizes I’m not going to get it. And I know I’m not going to get it, because Soobe is not in my vocabulary or in my product knowledge.

Out in the rental lot Tizi and I hunt for the vehicle among hundreds of rental cars. We go looking for it in the Drivalia section. I tell Tizi we’re looking for a Soobe.

“A Soobe?” she says.

I tell her I have no idea.

Halfway there it occurs to me I forgot to ask what color it is. On a tag attached to the key is a license number. But come on. Modern car tech comes to the rescue. When I press the button on the key that is more than just a key, a car somewhere squeaks like a mouse. I re-squeak it several times, and there it is, our ride for the next twelve days.

Based on the squeak, I was expecting a small car. Usually our budget Italian rental resembles a large roller skate, with enough room for two people and a suitcase. This Soobe is the biggest car we’ve ever rented over here. It’s also the bluest car. It’s royal metallic luminescent burn-your-eyes blue. Okay, I think, hard to park but easy to find.

“This is it?” Tizi says.

“A Soobe.”

“Yeah, but what is it?”

I walk around the car, looking for its name. Not a Fiat. Not an Opel. Not a VW. “It’s a dr,” I say.

“What’s that?”

My thoughts exactly.

Getting into a rental car, I always feel thrill and dread in equal measures. Thrill: Will it be new? Will it be sporty? Hey, a Lancia, cool. But dread? Will it be clean. Will we have a fender bender. One year in Chicago, I got into a rental car that smelled like a recently cleaned men’s room. We’re talking urinal cakes. But the big blue Soobe, we sense right away, is going to be okay. Smells good. Spacious. Comfortable seats.

I step on the brake, push the Start button. Nothing happens. Repeat the process, expect a different result. No go. Our seatbelts are fastened. We are prepared for take-off. Repeat the process. Same result. On the display, below the speedometer, these words scroll: Put your foot on the clutch, moron.

That’s me.

One of the disturbing stories in the news this week involved a Southwest Airlines pilot passing out in mid flight. I used to think the most disturbing message you could hear on a flight’s intercom system, after “kiss your ass goodbye,” was “Is there a doctor on board?” Not anymore. “Is there a pilot on board?” Would they have said that?

It’s a feel-good story. There was a pilot on board, a certified pilot from another airline. He got behind the wheel, and all systems were go. In this instance, go back. Back to the airport where the flight originated, to seek medical attention for the afflicted pilot.

Having just piloted the big blue hr Soobe from Bologna to San Marino, I pictured the certified pilot sitting down, looking at the instrument panel and thinking, “Okay, I don’t fly this particular model. But yeah, I can fly this plane.” Like me taking my place in the Soobe’s driver’s seat. Yeah, once I figure out how to start the engine, I can drive this car.

We’re five minutes down the road when I realize I need to adjust mirrors. How do I do that? Ten minutes down the road I want to adjust the heat. How do I do that in this high tech vehicle? Where’s the gizmo? And while we’re at it, just in case, where is the control for the wipers? Does a Soobe come with cruise control? What are all these buttons on the steering wheel for?

I touch a button in climate control for AC and a television screen lights up.

I can’t look. I want to look, but I can’t look. I’m flying the plane.

There is a time to familiarize yourself with these features, and it’s not when you’re merging with traffic on the tangenziale going 90 km per.

That night we attend a poetry reading. It’s a small room–it’s a poetry reading, after all–but all the seats are taken. A few minutes after the reading starts, I experience a faint jiggling sensation. It’s coming from the direction of my feet, and I think it could be seismic. A little more jiggle, then no more. Later on, the big guy sitting beside me begins to get restless–it’s a poetry reading, after all–and begins bouncing both legs in a nervous, rhythmic, theoretical gallop. And I think, Maybe the jiggle I felt wasn’t seismic.

Next morning I check. Yes, it was seismic.

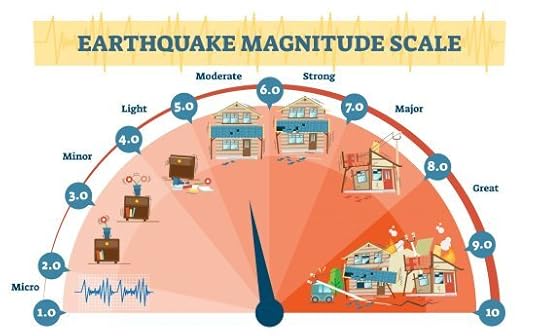

Four years ago, we felt two earthquakes over here. They were more than a jiggle. One was on the scale of: I’m taking a shower but I don’t mind stepping outside. In our building stairwell, excited voices echoed, doors were flung open and closed as residents took to the street.

Shortly after we arrived here on this trip, four weeks ago, there was a little earthquake, more than a jiggle.

You can go online and check seismic activity in any part of the world. In some places, Detroit, for example, it’s an academic exercise, a curiosity. Two little earthquakes in the last two years. If you’re in Italy, I don’t advise checking, because this country is a hot spot. They don’t talk about “the big one” over here, the way they do in California, but you begin to wonder.

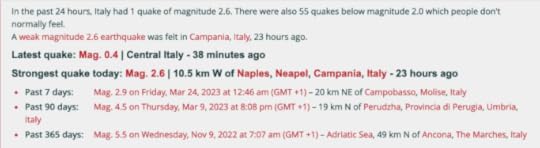

The site I consult for earthquake info over here is called Raspberry Shake. I appreciate the humor. The name calms the nerves, if only slightly. Here’s the news: “In the past 24 hours Italy had one quake of magnitude 2.6. There were also 55 quakes below magnitude 2.0, which people don’t normally feel.” Fifty-six earthquakes. In 24 hours.

At the poetry reading, it was a (very) minor earthquake. I’m putting my money on Mag 1.8, 22 km SW of Folignano, Provincia di Perugia.

How dangerous is it over here? What is the risk? Our daughter and her husband own an apartment down the coast in Pesaro, which is getting closer to seismic central. Fall, winter, and spring they rent the place. Their latest tenant, because of frequent jiggles, moved out recently, seeking a safer zone seismically speaking. Tolerance for risk varies. When it exceeds your limit, you act.

In the main, here as elsewhere, California, for example, I think people simply accept the risk. “It’s where we live.”

We’re lying in bed a few nights later. Tizi says she can’t sleep.

That’s never a problem for me. I tell her to try listing the fifty states of the union in alphabetical order. That tends to knock me out.

“There’s bad weather between Michigan and Florida, and those kids are on the road.” Our daughter and her two boys, she means.

I ask her: “How many M states do you think there are?”

“Lisa said they’re spending the night in Nashville.”

“There are eight M states,” I say. “In the M’s I think of them east to west. Maine, Massachusetts, Maryland . . . ”

“And I saw on the news, tornado possible.”

“Mississippi, Missouri . . .”

I saw the same weather forecast she saw: rain, heavy rain, torrential rain, unGodly rain; and tornado. They might have met up with those conditions in Nashville. Before we came to bed I saw a text message from her that was not reassuring. “Weather BAD. Hale. At least the car isn’t hydroplaning.” She’s crazy, our daughter. Don’t use the term “hydroplaning” in a text your mother might read.

Next day, late in the afternoon, we will see this headline: “The massacre at The Covenant School in Nashville . . . “

It’s an earthquake, a category 4 hurricane; an unspeakable unnatural disaster. Three nine-year-olds, three school personnel, shot dead. The assault weapons were legally purchased.

It’s where we live.

I drive through Rimini in our big blue dr, an SUV (the Italians, I’ve learned, say Soove). Day or night, it’s dangerous. Let me be clear: I am a danger to others.

Unlike back home, there’s a lot of pedestrian traffic here. People on foot, people on bicycles and scooters and motorcycles who take their lives in their hands slipping between, around, and past cars. And every 100 meters or so, there is a crosswalk. In the US, the crosswalk is a suggestion. Driver, would you consider stopping? People in cars think of themselves as primary. I’ll stop and let you cross if I feel like it. Here most pedestrians assume you will stop. You are supposed to stop. I’ve had to train myself. Stop. Night time is worst, in the rain. I could kill someone.

To lower the risk I pose to others, I scan the sidewalks, the crosswalks and gaps between bushes where an old lady on foot might step in front of me assuming I will stop. I’ve trained myself: don’t look at Soove’s tv screen, don’t try to do anything except watching, searching, to avoid hurting someone.

Next week we’ll fly home. Out over the Atlantic, traveling 500 mph at an altitude of 35,000 feet, the only thing I’ll worry about is will they run out of the chicken before they get to my seat. The real danger that day will be driving the Soove back to the airport.

When I was a kid in school, there were emergency procedures–mainly tornado drills. I think we also still practiced what to do in case of an A bomb. A few families in town had bomb shelters in the backyard. Mayhem was an abstraction. Today schools in the US have active shooter protocols. Every day is an earthquake. I’ve heard friends say when they go to a public place, they’ve learned to scan the area, with escape routes in mind.

It’s where we live.

March 22, 2023

Subtracting the Negatives

We have a new server at Nud e Crud, one of our favorite restaurants in Rimini. Tizi and I form attachments to servers. Dido at Passatore, Valentina at Marianna, Luccio in San Gregorio, Sergio at La Rivetta. We’re more than consumers passing through, paying for a product and service. We’re regulars now. The food, the transaction, the reunion, is personal. We joke, we chat. The banter is light. My Italian is good enough, I can usually join in. The new guy at Nud e Crud is Antonio. He knows us now. We’re getting there. It’s starting to feel personal.

“Where’s he from?” I ask Tizi one day. Native speakers, people who are from here, can usually locate individuals by their accent. A couple days ago at the local bakery, she placed the pastry chef, guessing he was from the north. And she was right: Venice. Today she says, with confidence, that Antonio’s accent is Lazio, down by Rome.

I tell her I can’t understand a word he says. Which effectively places me on the sidelines: observer rather than participant.

This happens a lot.

A few days ago, a Sunday, was Father’s Day in Italy. We went out to eat with our niece, her husband, and his mother. Malardot, where we are usually served by Federica or Sabrina, was packed. There was a new guy serving tables, a new guy who, everyone decided based on his accent, was from either Spain or Central America. I couldn’t understand a word he said.

“They’re really busy today,” Tizi said. “Let me talk.”

#

“Don’t objectify yourself,” Arthur Brooks writes in The Atlantic Monthly. “Thinking of yourself as an observer is better for your happiness than obsessing over being observed.”

Brooks makes a distinction between I-self and me-self: I-self the observer, the eye; me-self the participant, the actor-talker-sharer-giver-receiver.

Me me me. Can’t you just be? Yes, but it takes practice.

In a recent two-night excursion, another challenge. And some practice.

We’re on the southern edge of Orvieto, entering the underground tour. There’s fifteen of us. Plus the guide. It’s a good time to take shelter, as the sky has darkened and light rain is in the forecast. When Tizi and I exchange a couple words, an Italian gentleman next to me turns and says, “British?” No, I say, American. Then, as I usually do, pointing at Tizi I add, “Not her. She’s from San Marino.” He and I exchange a few words in English. When I compliment him, he shifts to German and invites me to join him, then tells me he can also speak Czech. He’s happy to show off a little, and I get that, because I too am a show-off and will blithely inflict my Italian on anyone who will listen.

We duck our heads, entering the cave, and proceed single file down a series of steps, to assemble in front of a large illuminated map, where the tour will begin. Our guide is in her 40’s, dressed in a spiffy blue guide uniform, with long brown hair spilling over her shoulders. She launches into her presentation.

“Sorry,” Tizi whispers to me. “It’s in Italian.”

Why, yes it is. I tell her that’s okay. I’ll pick up what I can.

The guide has a lot to cover and, in the manner of professional guides over here, launches into a discourse that is practiced, fluent, and scholarly, full of proper names and dates, along with some technical jargon.

We’re in a cave. So she has a lot to say about rock.

We’re in a cave, which means there is an echo, which puts me at additional disadvantage. Anyone who is hearing challenged, as I am, will tell you that echo is not their friend. It creates an auditory blur.

Right now I’m getting, in the sketchiest terms, a few echoes of Etruscan history.

“You okay?” Tizi whispers again.

“You can tell me all about it later,” I say.

For the fun of it now, as a thought experiment, put yourself in a cold, damp, dimly lit space 100 feet underground. It’s a walking tour, but you’ll be standing for most of the hour, listening to a dense lecture in a language you barely understand. Wanna sit? You can’t do that. Wanna lean? Best not too. You might damage the rock, which I’ve managed to glean from our guide is called “tuffo.” It’s a porous, friable rock, ideal for what these Etruscans were up to back in 600 BC.

There was a time, I confess, I would have wanted to run out the place screaming rather than move through a one-hour tour with the fifteen, unable to follow the talk. But I hang in there, in observer mode. It’s passive listening. I understand this:

Pigeons.

And I understand this:

Water.

And this:

Wells.

Olives.

Donkeys.

Inhabitants.

Romans.

Centuries.

Medieval.

1970’s

We continue the tour, the guide talks a lot, I look around and try to take notice. Here’s a press. Here’s a large stone wheel that’s 2600 years old. How’d they get that down here? My multi-lingual friend, I notice, has brought a flashlight. Every few minutes he steps away from the group, lights up a small section of the wall, and examines it. What’s he looking at? Another guy separates from the group, goes into his own private grotto, and coughs. People wearing masks adjust them. Here’s a well 90 meters deep that the Etruscans, with hammers and chisels, dug to find water. You can stick your head in the well and say, “Hey!” It echoes back, an echo I don’t mind.

“Amazing,” Tizi says.

#

Brooks refers to the via negativa. Via negativa is not a street, although it could be. (One of our favorite streets in Bologna is Via Malcontenti.) It’s literally “the negative way,” how mindful negatives can become a positive. “Everyone,” Brooks explains, “has what psychologists call ‘negativity bias,’ a propensity to notice the details you dislike over those you like in any situation.” The via negativa is subtracting the negatives.

Like you’re stuck in a lecture underground and can’t understand hardly any of it. Forget yourself, if you can. Put the negatives out of mind. That way lies happiness.

Ten years ago, in the Blue Grotto on Capri, we needed the via negativa. It’s a tourist attraction, like a natural cathedral. And it’s amazing, like a cathedral. You get there by rowboat, which in low tide passes through a rocky archway. The rowboat is piloted by a local dude. Think gondola and gondalier. We were pretty geeked. Once we got inside the grotto, bobbing up and down on the rising and falling waves, we noticed 1) that it was crowded (picture a large parking lot with no stripes, a lot of cars randomly parked—floating—willy nilly), and 2) that our pilot had no patter, nothing to say. He floated next to another boat and yacked with the other pilot in dialect for about ten minutes. I understood when he said “lunch.” And that was it. Possibly Tizi understood more, but he showed no inclination to talk to us. That’s what we took away from the tour. We were there, it was beautiful, the boat guy didn’t talk.

This was me-self plural. Us-self. What about us?

After our tour of the underground in Orvieto we spend some time in the cathedral, the Duomo. In there, you’re supposed to forget yourself. You’re small, God is big. Really big. That’s the point: to put you in your place. You would think in a church it’s time to invoke the via positiva–how you get to God. But how positive is it? You have to die to get there.

And really, we’re still on the via negativa here. For one thing, it’s cold. Can you just ignore that? For another, there’s the whole pervasive atmosphere of the sacred, which can be oppressive. The Duomo is an art museum, but with an attitude. So put that out of mind. And even the art element, it’s all too much, way more than you can take in in an hour or an afternoon or a day (or a week or a month). So, if you have one, you go to your happy place in there. You’re on alert. Maybe you’re into pulpits or altars, maybe statuary, maybe angels and saints. My thing is feet. And hell. I pick an apostle and take pictures of his feet. Then I look for images of hell, which you can’t miss. In the Orvieto Duomo I’m richly rewarded with images of hell, and I am struck, perhaps for the first time, by the fact that everyone in hell is naked. Those who make it to heaven can bring a small carry-on, they’ve got clothes, but in the other place, you’re lucky to get there in your underwear.

This focus, on feet and on hell, has given me a reason to go into a church, any church, in Italy. I’m like my multi-lingual friend with his flashlight.

#

We saw Antonio yesterday in Nud e Crud. Tizi talked to him. I did not, other than to say bring me the club sandwich and a quarter liter of red wine. What on earth is a club sandwich doing on the menu? What’s up with that table over there, with the four businessmen? And that guy in the corner, vaping between courses, can he do that? The two women at the next table clink glasses when their drinks arrive. Antonio wanders among the tables, looking perplexed today, like it’s all more than he can take in. And it probably is. I know the feeling.

March 14, 2023

It Ain’t Me

Three men stand in front of a billboard in Santarcangelo di Rimini. On the board are “manifesti,” broadsheets announcing the recent leave-taking of people or the anniversaries of their deaths, often with an indication of a mass that will be said for them. For each person there’s a color photo, how they wanted to be remembered or how their family wanted them to be remembered.

You see these boards in every town, and not just one board. Anywhere there’s a church you’ll see the boards and announcements. And in Italy, of course, there are a lot of churches. That means a lot of dead people, not in your face exactly, but not exactly off stage either. The Italians live with their dead.

A few days ago we were walking along the side of the Duomo in Rimini. I stopped to look. A half a dozen faces. How many years ago did this fine old man die? How old was this beautiful woman when she died? Here’s a nonna. I bet she was a good cook. You look and you start doing your death math. He’s gone three years; he was older than me. She lived to the age of 55. Wow, I’m way older than that now. The nonna was 80. But this guy, so well dressed, so obviously alive to the world when the photo was taken, was dead at 28. What happened?

The dead, pictured everywhere, are a grim attraction. You stop, look, and wonder.

Each time we come to Serravalle, we take a walk up to the cemetery. We visit Tizi’s relatives. The cemetery is a busy place. Quiet, holy. (The Italian for cemetery, cimitero, is also camposanto, holy field.) On the graves, on the covers of the tombs, are photos, the same photos that appear on the manifesti; with the photo, of course, are names and dates. The dead in the Serravalle cemetery date back to the 19th century. You see the transition, from old black and white photos then to color photos now. I’ve been coming here long enough, I recognize names of family friends and see faces of people I know. Or should I say knew? We visit Tizi’s grandparents, as well as a tomb where a lot of the family bones are collected. We bring flowers. The tombs get flowers. The bones get flowers.

Lately, down by her aunt and uncle’s graves, we find Mario, a guy from our building who was always sitting on a bench out front when we pulled up in our rental car. “Ben tornati,” he would say with a smile. And give us some tidbits about the weather, or the truffles, or some local gossip. Here’s Mario, we say now, gone at 78. We add him to our list of people to visit.

Here’s the town doctor who, when he came to our house when our then two-year-old daughter was sick, pried her mouth open with a soup spoon so he could see her throat. He’s gone. His twin sons are gone, younger than us by decades.

On our most recent visit, I stop in front of Gianetto (short for Giovanni), a great old guy who had a tabaccheria, news, and candy store on Serravalle’s one main street. He said whenever we walked in with our little kids, “You see this?” gesturing at all the candy, “this is all yours!” He was one of my father-in-law’s best friends. They belonged to a group they called The Twelve Apostles. They went out nights together for episodes of heroic eating. One night, when Gianetto was in the hospital, they actually snuck him out of the hospital for a dinner and then took him back to the hospital after dessert and grappa.

My tradition with respect to the dead is small town Midwest. Naturally there are decades of dead in town, but there’s not the same kind of public recognition and mourning.

Once a year my brother and I drive to visit our parents and a sizable field of Bailey relatives in Breckenridge. A 45-minute drive for him, 90 minutes for me. My maternal grandparents are a three-hour drive from Detroit. I haven’t been to that cemetery since they were buried there.

Yesterday in Civita di Bagnoregio, near the piazza where we parked our car, I saw a memorial for a soldier who died in Iraq, reminding me of how common war memorials are in Italy. There’s been a lot of war over here. In any city, in any small town, it’s not unusual to see a wall in a high foot-traffic area. On the wall are names and faces of the fallen. In Frontino recently there were two plaques, World War I and World War II, with names. It’s the everyday-ness of these observances that’s striking. Your grief, your gratitude, your awareness of your own mortality is present, is called to mind. Maybe that’s why a memorial like the Vietnam memorial in Washington, D.C., hits you like a tsunami. When you travel to see it, it’s a pilgrimage. When you get there, it’s a tidal wave of grief. Here the waves lap continuously at the shores of the living.

In casual conversation I’ve learned to say, “Sono ancora qui.” You see someone you know, you stop for a chat. When asked, How are you? You answer, “Sono ancora qui.” I’m still here.

Looking at those photos on the manifesti, I think, It ain’t me babe, it ain’t me I’m looking at. Sono ancora qui.

It Ain’t Me I’m Looking At

Three men stand in front of a billboard in Santarcangelo di Rimini. On the board are “manifesti,” broadsheets announcing the recent leave-taking of people or the anniversaries of their deaths, often with an indication of a mass that will be said for them. For each person there’s a color photo, how they wanted to be remembered or how their family wanted them to be remembered.

You see these boards in every town, and not just one board. Anywhere there’s a church you’ll see the boards and announcements. And in Italy, of course, there are a lot of churches. That means a lot of dead people, not in your face exactly, but not exactly off stage either. The Italians live with their dead.

We were walking along the side of the Duomo in Rimini a few days ago. I stopped to look. How many years ago did this fine old man die? How old was this beautiful woman when she died? Here’s a nonna. I bet she was a good cook. You look and you start doing your death math. He’s gone three years; he was older than me. She lived to the age of 55. Wow, I’m way older than that now. Nonna here was 80. But this guy, so well dressed, so obviously alive to the world when the photo was taken, gone at 28. What happened?

The dead, pictured everywhere, are a grim attraction. You stop, look, and wonder.

Each time we come to Serravalle, we take a walk up to the cemetery. We visit Tizi’s relatives. The cemetery is a busy place. Quiet, holy. (The Italian for cemetery, cimitero, is also camposanto, holy field.) On the graves, on the covers of the tombs, are photos, the same photos that appear on the manifesti; with the photo, of course, are names and dates. The dead date back to the 19th century. You see the transition, old black and white photos then, color photos now. I’ve been coming here long enough now, I recognize names of family friends and see faces of people I know. Or should I say knew? We visit Tizi’s grandparents, as well as a tomb where a lot of the family bones are collected. We bring flowers. The tombs get flowers. The bones get flowers.

Lately, down by her aunt and uncle’s graves, we find Mario, a guy from our building who was always sitting on a bench out front when we pulled up in our rental car. “Ben tornati,” he would say with a smile. And give us some tidbits about the weather, or the truffles, or some local gossip. Here’s Mario, we say now, gone at 78. We add him to our list of people to visit.

Here’s the town doctor who, when he came to our house when our then two-year-old daughter was sick, pried her mouth open with a soup spoon so he could see her throat. He’s gone. His twin sons are gone, younger than us by decades.

On our most recent visit, I stop in front of Gianetto, a great old guy who had a tabaccheria, news, and candy store on Serravalle’s one main street. He said when we walked in with our little kids, “You see this?” gesturing at all the candy, “this is all yours!” He was one of my father-in-law’s best friends and belonged to a group they called The Twelve Apostles. They went out nights together for episodes of heroic eating. One night, when Gianetto was in the hospital, they actually snuck him out of the hospital for a dinner and then took him back to the hospital after dessert and grappa.

My tradition is small town Midwest. There are decades of dead in town, but there’s not the same kind of public recognition and mourning.

Once a year my brother and I drive to visit our parents and a sizable field of Bailey relatives in Breckenridge. A 45-minute drive for him, 90 minutes for me. My paternal grandparents are a three-hour drive from Detroit. I haven’t been to that cemetery since my grandparents were buried there.

Yesterday in Civita di Bagnoregio, near the piazza where we parked our car, I saw a memorial for a soldier who died in Iraq, reminding me of how common war memorials are in Italy. There’s been a lot of war over here. In any city, in any small town, it’s not unusual to see a wall in a high foot-traffic area. On the wall are names and faces of the fallen. In Frontino recently there were two plaques, World War I and World War II, with names. It’s the everyday-ness of these observances that’s striking. Your grief, your gratitude, your awareness of your own mortality is present, is called to mind. Maybe that’s why a memorial like the Vietnam memorial in Washington, D.C., hits you like a tsunami. When you travel to see it, it’s a pilgrimage. When you get there, it’s a tidal wave of grief. Here the waves lap continuously at the shores of the living.

In casual conversation I’ve learned to say, “Sono ancora qui.” You see someone you know, you stop for a chat. When asked, How are you? You answer, “Sono ancora qui.” I’m still here.

Looking at those photos on the manifesti, I think, It ain’t me babe, it ain’t me I’m looking at. Sono ancora qui.

March 8, 2023

Mastery of Mystery

We arrive in San Marino on Ash Wednesday afternoon. To get here we’ve traveled all night and through most of this day. We unload bags, turn on the water, and raise the heat in the apartment. Tizi makes a bed. We pull sheets off a couple chairs so we have a seat in the morning. Early evening we go for a walk. First night here, it’s important to stay awake as long as we can. Down below the apartment, we walk the road that will take us to the tunnel that will take us to the cemetery. We’ll get there eventually. But not tonight.

A few minutes before 8:00 the church bells ring, calling the faithful to Ash Wednesday service. Tizi says, Let’s go. The smudge on the forehead is not part of my tradition, if I can be said to have a tradition, but I go.

We go. To the church where she was baptized.

For years on Ash Wednesday, when I was still teaching, on my way to work if I remembered I would stop for ashes at the Catholic church near our house. Students, my Arab students in particular, would notice the mark on my forehead, and I would take the opportunity to explain a little about Lent, about the forty days, and liken it to Ramadan, their period of fasting. “Why do you fast?” the American kids would ask the Arab kids during Ramadan. “To remember the poor,” they would say. I always had the impression that they were proud of their fast–they struggled with it, physically, you could see that–but they were invested in it. They were lifted up.

This night the church in Serravalle is full. The creaky old wood pews are full. Chairs have been set up next to them. People stand along the walls, waiting for ashes to go. An usher shows us to a couple chairs.

The service is long. There are readings and a long homily. Standing next to the organist, a nun sings into a microphone. She has a little girl voice. Coming in, I thought we would queue up, walk down the aisle, get the ashes, and hit the road. Not tonight. Tizi tunes into the liturgy, as she is able to do. I do not. It’s in Italian, after all, not my language of worship. I don’t know their hymns. And I don’t know yet, in any real sense, the experience of faith. I am not fluent in faith.

Every now and then, when she has to, she nudges me awake with her shoulder.

One year we were in Venice on Ash Wednesday and went to St. Mark’s for ashes. I was pretty geeked. I thought, Now these are going to be some premium ashes. Gimme the smudge.

It took a while. There were red caps at the altar. They had a lot to say. It was a service, but it felt like so much more than that at St. Mark’s, the great Byzantine temple with the mosaics and the undulating marble floor miraculously afloat on the swampy ground beneath it. You don’t mind waiting. You feel small, you feel a sense of awe, which is the whole point of such a place, the way you feel small and you feel awe standing at the ocean shore or at the edge of the Grand Canyon. So it was okay.

When we finally got up there that night in Venice, and I held out my head for the smudge, instead of making the sign of the cross on my forehead, the priest measured out and poured a quarter teaspoon of ashes on top of my head, in my hair, and sent me on my way.

I wanted to be a marked man in Venice. I know that’s ostentation, which is probably a sin. But still, it was a letdown. That night, if I was marked, it was just between me and God.

This first night that we’re back in San Marino, when it’s my turn for ashes in the church of Serravalle, it’s the same thing. On my head, in my hair.

Walking back to our seats, I see a few familiar faces. Hey, there’s Marina. Hi! And hey, there’s Checco and Lilliana. Hi, you guys. A small wave, I hope, is okay.

“So,” I whisper to Tizi, back in our seats, “now we fast.” She nods and smiles.

Fast like an Italian.

I know that gluttony is one of the seven deadly sins–it’s worse, I think, than ostentation–but somehow the Italians sidestep that difficulty. They can do Lent and indulge at the same time. The bakery up the street, called La Baguette, more pasticiaria than bakery, calls to us, offers sweet delights. Last year as St. Joseph’s day approached–Italy’s Father’s Day on March 19– we discovered zeppole up at La Baguette. Picture a round pastry, a tawny hockey puck, a cream puff pumped full of light yellow pastry cream, dusted with powdered sugar, topped with a dark cherry. I wish they made them the size of a frisbee.

Within 24 hours of being marked with ashes, Tizi and I split a zeppole. We split one. This is our sacrifice, a gesture of the fast, having half a zeppole rather than a whole one.

“We really shouldn’t eat these things,” I say.

She takes a sip from her cappuccino. “Sure we should.”

“We could make zeppole our Lenten sacrifice.”

Another bite of zeppole, another sip. “That would be crazy.”

“Do you think Checco eats Zeppole during Lent?”

“Of course,” she says. “These are so good.”

I make a mental note: Ask Checco.

Checco (pronounced KEH-ko) is a celebrated local poet. He writes, publishes, and performs in San Marino dialect. His project, his marvelous contribution to local culture, is preservation of the local language, as well as celebrating local traditions and experience. Before he performs a poem, reciting from memory, he reminds the audience of word origins and figures of speech, connecting them to daily life, to the rhythms of the seasons and work, to the nature of family life. His work is poetry. But it’s also history and anthropology. Along with a great sense of humor he has a fine ear and a great heart. At his readings I’ve seen him bring Tizi to tears. I listen politely, eagerly, but because it’s dialect, I understand next to nothing.

His house is on the route of one of our walks, up the hill behind our building. An uphill walk smacks of penance, so we go for it. On the gate in front of his house Checco attaches copies of poems he has printed, both in dialect and in Italian. I can sort of read the Italian.

Today, a Sunday, we’ve skipped church and walked. On the gate Checco has posted a poem that asks what God was up to when he created the world, “il cielo, il mare, la terra, l’aria, e gli astri, il sole, la luna, le stelle che sono cosí belle da vedere e contemplare.” A list, obviously, the heavens, the sea, the earth and the air, the sun and moon, and the stars–all so beautiful to see and to contemplate… “Mille generazioni! E si nasce e si muore da migliaiia di anni…” So many generations of us. We are born and we die, over thousands of years.

And what for?

You meet people of faith who just seem to have a vibe. With God, I mean. They don’t throw it in your face. They just have it. It’s like having an ear for music, or they’re good at math. In Checco’s case when he recites, you see a concentration of heart and mind that’s so human and so beautiful. To see him in church, to hear him talk about “il Signore,” you see he gets it.

My nephew, gone a decade now, was like that. He had the vibe. When I sat next to him in church, after communion he would come back to the pew and recite his prayers, aloud, praying for people he loved, his friends, his teachers, his family. You thought, well, if there’s a God, he’s inside Joey right now. As I listened, I thought, Pray for me too, Joey.

Checco writes, along with beauty “c’é dolore, le carestie, la fame, e la terre ogni tanto trema sotto i piedi!” There’s pain and suffering in the world, famine. Every so often the earth trembles beneath our feet.

Does it ever.

“You achieve,” Adam Gopnik writes in The Real Work: On the Mystery of Mastery, “something that, if not exactly mastery, is at least an actual accomplishment, a happy patch, a bit of [mental] software that you had never had before.” Gopnik is talking about the ability to draw, developing his hand at painting, one of those skills that some of us–me, for example–say that we absolutely do not have. Knowing yourself is knowing what you think you lack, knowing that you are tone deaf, or art deaf, or math-less, or dance-less–you name it, there is a skill, an art, a capacity that eludes you. I wish I could ——– (fill in the blank). Gopnik celebrates “repetition and perseverance and a comical degree of commitment,” suggesting hopefully that breakthroughs are not out of reach.

“Having (fill in the blank) now, however poorly you install it, makes yours an expanded and extended mind and body, a significantly different self than the one you were assigned at birth.”

When I read this, I think of standing on the sidewalk outside the church in Serravalle that night, talking to Marina, talking to Checco and Lilliana, marveling at how in acquiring a second language, you acquire a second self, a persona that is constituted by the grammar and sounds and rhythms and gesticulations of the new language. I never thought of myself as good at languages. My last year as an undergraduate, I took some French and fell on my face. I could pass a grammar test (just barely), but my mouth was useless. I could not speak.

Standing in front of the church, or down at La Baguette, I have a happy patch that very much feels like a second self. I prattle, happily. I gesticulate. This learned fluency causes me to wonder about the mastery of mystery, if I might apply myself to that and become fluent in faith.

I just might. But not today.

March 2, 2023

Keep the Rats Far Hence

It’s pouring rain when Tizi comes out of Marcello’s around 11:00 a.m. It’s her hair salon in Pesaro. Shortly after arriving in Italy, we go to Marcello’s, and she gets updated: the shampoo, the head message, the comb-out, the trim, the set, the poof agent, the anti-friz agent. All of Marcello’s ministrations which she so loves. During the cut I usually take a walk down by the sea or find a coffee bar and read the news.

It’s raining hard today. I notice my old Rockports, they must be 20 years old, have sprung a leak. It’s one of the ugliest shoes ever made, but in an understated way, ugly that doesn’t call attention to itself. All these years it has pleased me to think that an Italian, any old Italian in this shoe-obsessed society, would cast a downward glance in the direction of my feet, notice my Rockports, and look up with barely concealed horror. Alas, I wore them long and I wore them well.

Hard rain is in the forecast all day, so I go with Nickie to Globo and buy a pair of over-the-ankle boots, wondering, as I pay the bill, if this will be the last pair of shoes I buy over here. (There are moments one becomes conscious of one’s age. Yesterday, standing in front of the fruit and vegetable stand, up in the piazza, on one side of me, I would have once called her an old lady, wearing a plastic bonnet over her hair-do; on the other side, I would have once called him an old man, with a hat and cane. Both, I realize now, are my contemporaries.)

The shoes fit great, look great, and will keep my feet dry. We meet Tizi at Zanzibar, the bar outside Marcello’s. Her hair is gorgeous. I tell her Marcello out-did himself.

“You really should have one of those things,” I say.

“Things.”

“In case of rain. In her purse my mother always had a plastic hair-do cover. It folded up like a pack of gum.” On her head, loosely knotted under chin, it looked like a wind-blown geodesic dome.

“I had one of those,” she says.

“You.”

“We all had them. For when we got dressed for church and it was raining. Some of the girls ratted their hair. They didn’t want to spoil it.”

“Spare the hair. Spoil the rat.”

“What?”

“Never mind.”

“All the girls,” she says. “All the ladies wore those things.”

It’s late enough, almost noon, I can have a glass of white wine while she and Nickie have a late cappuccino.

#

We have lunch at Gra!, next door to Rossini’s house. Gra! Which calls to my mind the paucity of one-syllable words in Italian. Ciao! Beh! Gra! Let’s see, there have to be more, many more one-syllable words. I make a mental note to be on the lookout for them.

On the menu are strozzopreti picchio pacchio. Later, when I check on the origins of that term, I learn picchio pacchio is a Sicilian dish, possibly a version of the sicilian pic pac (single syllables), reminding me of Tizi’s mother, who would refer to her speedy seering of a piece of meat in a pan for the kids as tric e trac (single syllables).

Over lunch, we briefly return to the subject of rats.

“Did you rat your hair?” I ask.

“Sure, we all did.”

“But Tizi, rats.”

“I know,“ she says.

Tizi hates rats. Who doesn’t? But hates them with a shriveling sense of loathing and disgust. Any screen time given over to rats on TV or in a movie, she closes her eyes while I fast forward.

#

According to the Italian newspaper La Repubblica, there are 15 million rats in Rome (more rats than Romans), 13 million in Milan and 10 million in Naples. It sounds like they do a rat census.

In Rome they deal with three three types of “roditori.” Sewer rats, tree rats, and mice. Arriana di Cori, the journalist who has the rat beat, refers to the sewer rat’s big feet (ugh) and the tree rat’s invasion of homes by way of their roof tiles. It’s all terrible. But the idea of rats in trees is singularly unbearable.

To put this in perspective, in New York City they number the rat population at 2 million. They’re looking for a rat czar in NYC. In Rome they’re undertaking a program called “derattizzazione,” de-rattification. Who you gonna call to unrat Rome? Rat busters.

Derattizzazione. That’s a lot of syllables. In the entire article, what I’m looking for is not only a solution to the rat problem, though I devoutly wish that for all of mankind. I’m also looking for one-syllable words. They’re there, all right, the little words: articles, prepositions, conjunctions, pronouns, what we might call function words. Otherwise in Italian it’s two syllables or more, topo (the word for mouse), ratto, derattizzazione.

#

You have to wonder: Why rat?

How did a loathsome animal, universally reviled, come to be associated with a woman’s hair? With coiffure?

When I consult Yesterday’s Thimble, the scholarly journal I turn to with questions like these, I discover that rats were useful for maintaining a high society lady’s high hair. The rat consisted of a mass of women’s hair harvested from a brush, collected in a net, pinned to her living hair, providing lift and height. So far so good. On the other hand, this too from rats in hair history: “The pomades to hold these styles together were made of beef lard and bear grease. Because these women paid a high dollar amount for the hairdos, they kept them for a week or two. The hair became rancid and would often attract vermin while the mistress slept. That is where the term, her hair is a ‘rats nest’ originated.”

#

When I get home, I look at my new shoes. I really look at them. They are a rat-colored shoe, I now realize. They look fine on my feet, but they could be browner or blacker; less rat. But they repel water, just as I wanted them to. The brand name is Grisport. It’s an Australian company whose manufacturing center is in Italy. On the side of the shoe, emblazoned in yellow, is the word VIBRAM. I don’t know what that is. They don’t vibrate when I walk. Should they? On a very small metal tag attached to the side of the shoe I see Gritex. I can’t really tell if the shoe is made of leather or some kind of composite. You never know these days. Maybe Gritex is the shoe manufacturer’s version of naugahyde.

I could have bought a different shoe, called Fighter. The tagline on the box read, “Specialized in the worst land.” I was almost persuaded. It would have been great to point at my shoes and recite that selling point.

But I went with the rat-colored shoe, hoping for a vibe when I walked, on a shoe made to last.

Tomorrow, haze and drizzile. Let it rain. But keep the rats far hence.

February 28, 2023

America Goes Left

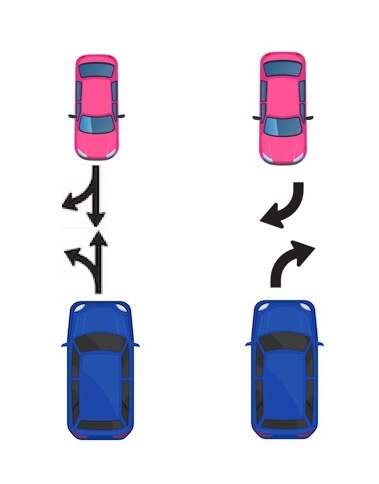

Watch out. You’re an American in Italy, and you’re about to execute the ceremonial cheek kiss. How many kisses, one or two? That problem will take care of itself. The peril is in the prelude.

In the US, at the onset of a hug (or a cheek kiss—if we did that), we tend to go left. We lean forward and veer gently to the left, extend arms, and embrace. In Italy, they go right.

Imagine that you are a Buick, a big American car amongst go-cart-size italian cars on a city street in Italy. You approach an intersection. Ahead of you, coming toward you into the intersection, a Fiat. The light is red. You both stop, face to face across from each other. When the light turns green and it’s time to move, you press on the gas and execute a left turn. That’s what we do in the US. We go left and merge. But you’re in Italy, where the Fiat goes right.

There are two awkward outcomes: a head-on collision, a kiss on the lips (or more likely a face smash), or, both cars complete their turns with an inevitable fender-bender. You both feel foolish. But there’s no doubt about who’s at fault.

American, turn right.

February 27, 2023

And Now the Letter H

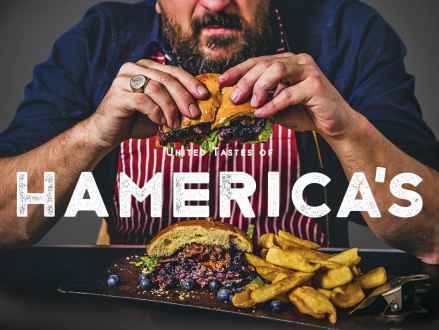

Today I discovered Hamerica.

Make that Hamerica’s. It’s a chain restaurant in Italy “dove vivi l’esperienza degli States e provi i migliori hamburger fatti in Italia con un gusto completamente americano.” Best hamburger in Italy, they boast. Just like being in the States.

Walking through Rimini this morning, we passed what used to be Picnic (the Italians say Peek-NEEK), a restaurant that had a huge vegetable buffet and garden seating and a very cordial and friendly old waiter named Roberto. Picnic closed ten years ago and was replaced by a tapas restaurant that did not survive. Now it’s Hamerica’s.

Hamerica’s was closed this morning. If it had been open, I might have gone inside, not for a genuine Hamerican hamburger but to ask, Guys, what’s with the H?

There are five letters in the English alphabet that don’t exist in Italian: J, K, W, X and Y. As for H–they call it “acca,” sounds like AH-kah–it might as well be missing, as it is not pronounced. At Hamerica’s I’m sure they say welcome to America’s. We serve amburgers.

It’s kind of cute. And very puzzling.

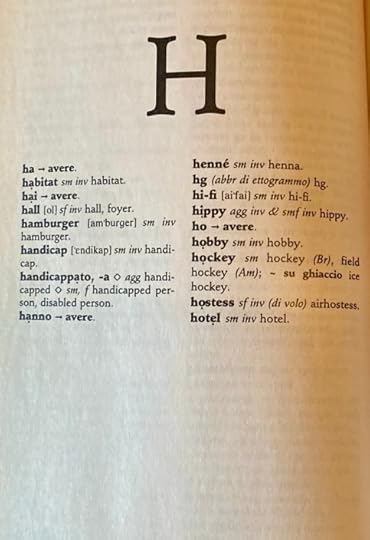

I got to wondering about H words. When we got home I pulled my Larouse English-Italian dictionary off the shelf and turned to the H words. It’s an old paperback edition, with 45,000 translations. In the H’s, here’s what I saw:

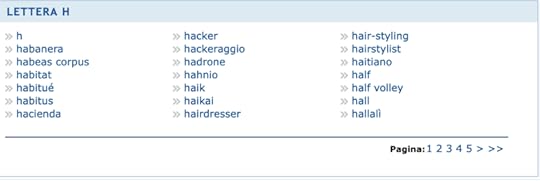

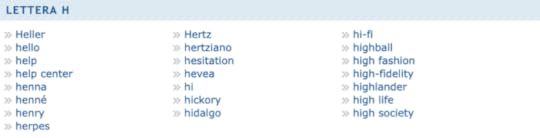

That was it. Next I consulted the online Hoepli Grande Dizionario Italiano, thinking I would search all the H words and maybe count them. They are a lot of them (Hoepli, for example). Here’s page 1 of the search.

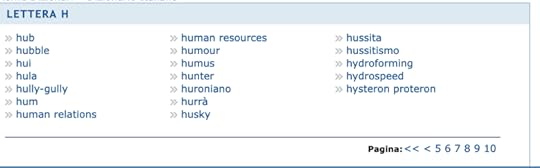

Mostly words imported from English. I notice “hackeraggio,” a wacky italianization, which is kind of like hackerage, the act of hacking. More H words:

It’s unlikely I will ever encounter the word hi-fi or hully-gully among friends, but I would give anything to hear those words spoken. With the H dropped, hi-fi would sound like E-fee and hully-gully ooly-GOOLY.

When I learned to conjugate the Italian verb avere (to have) I questioned neither the presence of H: ho (I have), hai (you-singular have), ha (he/she/it has), nor the absence of H: abiamo (we have), avete (you-plural have), nor its mysterious reappearance: hanno (they have). I can think of no other Italian verbs requiring an H.

Over time, I learned the utility of H, when it appears with the letter c and g. Spaghetti without the letter H would sound like spa-jetti. Michelangelo would sound like Mitchelangelo.

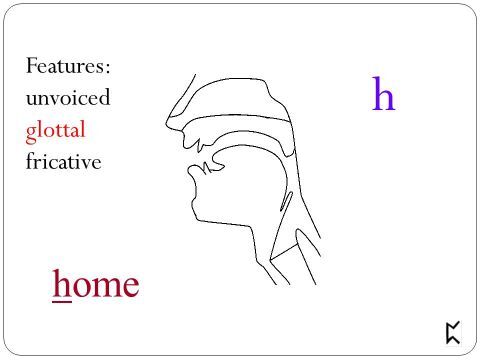

The plot thickens when we consider the voiceless glottal fricative, aka the gorgia toscana or “tuscan throat.”

You might wake up one morning in your Florence hotel and, in the breakfast room, inquire about the weather and how you should dress. Setting down your cappuccino the server might say, “Oggi fa haldo.”

Don’t bother looking for haldo in your Larouse.

The word “caldo” just emerged from his tuscan throat. And in this case, strangely, you hear the letter H. Any Italian travel book will warn you about this curious phenomenon, probably with this illustration: a coca cola with a short straw, una coca cola con canuccia corta, una hoha hola hon hanuccia horta. When they say a C word in Tuscany, they make it an H word. Case closed. Or as they might say in Florence, Hase hlosed.

I’ll have H’s on my mind as I continue my unt for amburgers in Italy.

Stuff happens, then you write about it

- Rick Bailey's profile

- 31 followers