Rick Bailey's Blog: Stuff happens, then you write about it, page 11

October 11, 2023

The Birds and the Beatles

I’m reading a New Yorker article about Paul McCartney at the breakfast table one morning. At the top of the page there’s a black and white photo of the Beatles, circa 1965. It’s the year, the caption tells us, of Help! and Rubber Soul.

My wife and I are leaving for Italy in a week or so. I’ve been downloading stuff to my Kindle to read while we’re away. I’ve got enough to last me quite a while, some novels (a few trashy ones, a few edifying ones), Clive James’ Poetry Notebook, a bunch of articles from the New Yorker, the New York Review of Books, and the New Republic. (I guess I’m keeping it New this spring.) When language fatigue sets in over there, and I know it will, with the constant strain of trying to listen very fast to decode flights of Italian, it’s a pleasure to lie down in silence and read in my own language.

“Photo by David Bailey,” I say to my wife. Our son’s name. “How about that?”

“What?”

“This article about Paul McCartney. It has a photo by David Bailey.”

Hmmm.

I give her a minute, then ask, “Who’s your favorite Beatle?”

“Don’t start.”

She’s reading a book called Agents of Empire: Knights, Corsairs, Jesuits and Spies in the Sixteenth Century Mediterranean World. The bibliography is 40 pages. Good lord.

“Are you taking that thing on the plane?”

“Maybe.” She pushes a small taste of eggs onto her espresso spoon.

“It’s a brick.”

“Jesuits,” she says. “I love the Jesuits.”

I hum a few bars of “When I’m Sixty-Four.” Two pals and I turn 64 within a few months of each other this year. I’ve suggested, more than a few times, that we should have a “when I’m sixty-four party” sometime this summer, to celebrate ourselves.

A few days later, my wife and I are upstairs packing. It’s mid morning. I’m tossing power cords for my phone and Kindle and laptop into a carry-on when I realize I’m not wearing any pants. What happened to my pants?

Later this day I will drive 90 minutes north to visit my old friend Brian. His caretaker Sheila has told me he’s not quite himself. It’s how she knew something was wrong. Listening to music in the car, piped from my iPhone into the radio, I make a mental note of oldies I’d like to play for him. “I’ve Got Friday on My Mind,” by the Easybeats. Cyrcle’s “It’s a Turn Down Day.” The Beatles’ “Dr. Robert,” so we can hear that scratchy guitar and lush chorus. I’d like to see him react to the organ solo in Bonnie Raitt’s “We Used to Rule the World.” In the car I play the music loud, today even louder than usual. I know I probably shouldn’t. My wife and kids tell me I’m getting a little deaf. (A little?) These days the car and treadmill are the only places I listen to music. I can’t help myself. I want it loud.

He’ll be sitting in his wheelchair at the kitchen table, his back to the doorway I walk through. I rehearse the scene in my mind. “Remember this?” Sitting across from him, I’ll play part of a song. I’ll wait to see the look of recognition, watch him travel back in time. “How about this?”

When my mother was sick and I made this drive, I listened to podcasts, for reflection and for laughs. For these visits, I want bang and bash. I want nostalgia.

#

We bought every Beatle album as soon as it hit the store. This was, of course, back in the vinyl days. The first three or four lp’s, in mono, cost less than five dollars. We took them home, put them on the turntable, and sat down to listen. It was “close listening,” almost like the close reading of a poem advocated by the New Critics. In the front bedroom of Brian’s house on 3rd Street, we sat on the floor and played the records over and over, holding the album covers, like holy objects, in our laps. There was a photo or two to look at; on the back, a song list. You listened, and you looked. “Meet the Beatles,” headshots of four young guys in partial shadow; twelve songs, the longest of which was “I Saw Her Standing There” (2:50), the shortest, incredibly short by today’s standards, “Little Child” (1:46), produced by George Martin, for Capitol Records.

Years later, my kids went totally digital. They bought cd’s and queued up the songs they wanted to hear. On some cd’s they listened to only one or two songs; that was it. Back in the vinyl days, we listened to the whole album, every track all the way through, even the songs we didn’t particularly like. Ringo singing “Act Naturally.” Really? To lift the needle, move it to the song you liked, and set it down, aiming for the barely visible gap between tracks, was to risk scratching the record.

A scratch would last forever. That was the thing about vinyl.

And now it’s back.

I have purist friends who could explain why vinyl is better: the sound profiles you get in analog are richer, far superior to the sterile precision of digital. I guess I get that. I’m still kind of an analog guy. I look at the clock and say “a quarter to” and “a little after,” it bothers me that soon kids will no longer be able to decode the face of a clock and tell time, the way many of them will never learn to write in cursive. I remember tuning in radio stations on the AM radio station in the car. Even today, I like a speedometer needle. I go about seventy mph (not sixty-seven) when I drive up to visit Brian.

I should ask him, What do you think about the vinyl craze these days?

I know what he would say.

Who gives a damn?

#

He’s sitting in his wheelchair with his back to the door. The dogs bark when I walk in. There are seven of them. It takes a minute to calm them down. Brian gives me a crooked smile and says, “How the hell are you?” It’s his usual greeting. He has a full beard, a lot more salt than pepper, and he’s wearing a hat. It occurs to me that in all the recent pictures of him I’ve seen, he has that hat on. When I ask him how the hell he’s doing, he turns his head and points to his hair, slate gray, wisps of what’s left of it hanging down. It’s the radiation, he says.

I figure we’ll get a few basics out of the way, before getting down to basics.

Sleep?

He says he sleeps just fine.

Appetite?

He says he’s an eating machine.

Pain?

Not even a headache. If the doctor didn’t tell him he was sick, he wouldn’t even know it.

I ask if he’s ever had a beard before.

Couple times.

He’s sixty-four years old, a September birthday, a year older than me. Three months ago Sheila organized a benefit. It went from noon to nine at the Elks Club bar in Bay City, all music all the time, played by over 40 years of musician friends in the area. Brian packed the place.

I tell him I’m thinking about a “when I’m sixty-four party” for me and a few pals this summer. What does he think?

Yup.

Next to the kitchen table, a tv set displays weekday afternoon programming. He watches it while I ask more questions, about his sister, son, nephew, a pal we call Easy Eddie. I’m thinking about my song list when he wonders, Hey, what’re we going to eat?

He’s sixty-four years old, a September birthday, a year older than me. Three months ago Sheila organized a benefit. It went from noon to nine at the Elks Club bar in Bay City, all music all the time, played by over 40 years of musician friends in the area. Brian packed the place.

In this New Yorker article, published in 2007, Paul McCartney confesses to dyeing his hair. He also confesses to being freaked out about actually being sixty-four. “The thought is somewhat horrifying,” he tells the interviewer. “It’s like ‘Well, no, this can’t be me.’” The article is contemporaneous with the release of an album called “Memory Almost Full,” which the interviewer describes as “up-tempo rock songs…tinged with melancholy.” I know the album. When it came out, I listened to 30 seconds of each track at the iTunes Store, bought one song, “Dance Tonight,” for $1.29, and downloaded it. It’s a jaunty piece with a kazoo solo in the bridge.

The writer mentions the famous deaths: Lennon, Harrison, Linda.

McCartney, I learn, was sixteen when he wrote “When I’m Sixty-Four.”

When Brian and I were that age, we had begun to realize we were not going to be the next Lennon and McCartney. We had written exactly one song together, called “If I Could Dream,” which some years later he managed to get recorded with a band he was in, graciously crediting “Bailey and Bennett” in parentheses beneath the song title as the composers.

I come back from Mulligans with two bar burgers, mushrooms and mayo on his, and French fries. The dogs bark. Four or five of them eventually settle under the table. We eat our burgers, watch a little more tv, and I think again about my song list. Maybe I won’t play the songs after all. Who wants to listen to music on a phone, anyway? In the kitchen it will sound like a cheap transistor radio.

I say, “Hey, remember ‘It’s a Turn Down Day’”?

He looks at the tv for a bit, then turns my way. “The Cyrcle,” he says. “They were a good band.”

The show we’re watching to is called The Doctor. It’s talk. Two men, two women. One of the men is dressed like a doctor. They’re discussing castration as a way of punishing rapists. Or maybe it’s a preventative measure. The man dressed as a doctor explains that there is both surgical and chemical castration. The two women agree that, either way, it’s an extreme measure. They are both against it.

I try another one: “Remember ‘I’ve Got Friday on My Mind’”?

It takes a minute. He turns away from the tv and gives me a partial crooked smile and a nod. “Good song,” he says.

I know the nod.

Sheila says, “Getting tired, Brian?”

It’s for me. Well, okay, I think, that’s enough.

We sit together for a while longer, through the rest of my fries. Brian takes a bite or two from his burger, gazes at the tv. Before going to commercial, the doctor previews the next segment of the show. They’re going to talk about a woman’s cancer treatment. The woman on screen looks familiar.

“Is that Bruce Jenner?” I say.

Sheila says it’s not Bruce Jenner. It’s a real woman.

“Goddam,” Brian says.

We watch a few more minutes in silence. I get up to go. The dogs rouse and congregate around my feet. I tell Brian see you in a month or so, shake his hand, and lean down for a long hug. “You hang in there now,” I say. “I’ll be back the middle of next month.”

He nods, says thanks for coming, Richard.

“See you, right?”

He nods. I’m pretty sure he nods.

About the time I get to the freeway, which takes ten minutes or so, my iPhone shuffles to a favorite Beatles song. I play it loud and sing along: “You say you’ve seen certain wonders, and your bird can sing.” That would be another song to mention, on another visit.

A few days later, my wife and I are upstairs packing. It’s mid morning. I’m tossing power cords for my phone and Kindle and laptop into a carry-on when I realize I’m not wearing any pants. What happened to my pants?

“Have you seen my black sweater?” my wife says.

When did I take off my pants? For a while now I’ve been walking into rooms only to find I can’t remember why I’m there. I’m used to that. Like tinnitus, it comes with age. Losing my pants is new.

“Did you hear me?” my wife says.

“I heard you.” I look around the room, feeling mild panic. No pants, anywhere. “Which black sweater?”

I stand there, marveling at this altered state. Then I remember: I took them off in the other room, in front of the closet, so I could try on another pair I had fitted a while back.

“I’m losing it,” she says.

There they are, the pants I tried on, in the carry-on. So the other ones are over there?

“Can you hear anything I’m saying?” she says.

“I hear you fine.”

We’re all losing it.

One of these days I’ll have to get my hearing checked. I sort of don’t want to know. I think about my parents growing old, my father and all his hearing aids. There were owls in the woods a half a mile away from their house. My parents almost always slept with a window open. For years they said they heard owls all night. One day my wife and I were up for a visit. When I asked about them, my mother said yes, the owls were still there. Then she added, “Your dad can’t hear them any more.” I think he took it in stride. What choice did he have? Still, it broke my heart.

One day it will happen to me. I’ll wake up, look for my pants, and I won’t be able to hear the birds and the Beatles. I’ll have to remember to consider myself lucky.

October 8, 2023

iSmell–coming soon to a nose near you

When I was a kid, I loved to watch my father shave, the brush, the whip-cream soap, the razor, and most of all, Old Spice. The bottle alone, with its ocean blue galleon and red curlicue font and its peg-leg cap, was exotic. Some nights, once he was done shaving, he would pat my cheeks with his Old Spicy hands, and I would walk out of the bathroom feeling like a seafaring boy. Soon after, of course, I would go back to smelling like a boy.

Then came seventh grade.

In second hour gym class my locker was next to Ronnie Fritz. After showers one day, once we were dressed for our next class, he started splashing stuff on his face.

“What is that?” I said.

“Cologne.” He screwed the cap on the bottle and showed me. “It’s called Canoe.”

Cologne. I thought it must be after-shave, only different. I was still a few years from shaving. But something told me I was ready for cologne.

“Lemme see that,” I said, leaning in for a whiff.

Junior high boys were already smelling up and down the hallways, with Hai Karate, with English Leather. Eddie Maurer wore Jade East. Ricky Burmeister and Mike Howe swore by Brut. Dave Marolf was a British Sterling man.

“Peggy Bohnoff,” Ronnie Fritz said to me in the locker room, “loves Canoe.”

It didn’t smell like a canoe, which is probably good. It smelled like a floral disinfectant. I upended the bottle, wet an index finger, and daubed some on my jaw. Ronnie Fritz nodded encouragement, said I would be a girl magnet. I shook a few drops into my hand, rubbed Canoe on my cheeks, then a few more drops, and then a few more, applying it generously, luxuriously, all over my face.

We closed our lockers, tied our shoes, and went to third-hour class.

I lifted my hands to my face, sniffed at the air around me, feeling flammable.

It was social studies with Mrs. Smith, until 11:28; then lunch. My seat was in the right rear corner of the room. About five minutes into class, I realized I was too much in the Canoe. I tried to pay attention to what was what happening in class, but I all could do was picture fumes rising from my upper body, shimmering in the air around me, a toxic chemical aura. No one seemed to notice, but I was in agony. I had to do something. I couldn’t wait until lunch. I was asphyxiating myself. Finally I went to Mrs. Smith’s desk and asked to be excused to go the bathroom, where I pulled down lengths of brown paper towel, wetted them in the sink, and scrubbed my face, trying to erase the scent. I pumped foamy white soap from the dispenser and sozzled it around my palms, lathering my chin, cheeks, upper lip, then rinsed and regarded by red face in the mirror, trying to smell myself.

Back in class, a few minutes passed. I lifted my hands to my face, sniffed at the air around me, feeling flammable. I reeked. I told myself: I will never do this again.

Certain days back then, when the wind came out of the northwest, you could smell Dow Chemical in my hometown. The plant was eight miles up the road in Midland. It gave off an acrid smell, a chemical stench that surprised you every time. And the thing is, you couldn’t not smell Dow on those days. Driving through Midland, past rust-colored tanks, past switching stations and distillation units connected by endless intricate networks of green pipe and valves, you could close your eyes and unsee the industrial sprawl and the sick greenish air. But there was no escaping the odor molecules pinging across your olfactory receptors.

It is commonly thought that the human sense of smell is underwhelming, nowhere near as powerful and accurate as that of other creatures. Humans are sight-dominant, perhaps because we walk upright. We have noses, not snouts. D. C. McCullough, writing for The Guardian, takes the opposing view, observing that our sense of smell is both, he writes,

“instantaneous and highly specific and accurate.” Odd, if true, because the language we use to describe scent is nothing if not minimal, even impoverished. Smells good. Smells bad. Smells sweet, sour, floral, rotten… Yet smell scientists celebrate the human nose. According to the Public Library of Science Publication for Biology, “Humans outperform the most sensitive measuring instruments. Test results indicate that humans are relatively good, perhaps even excellent, smellers.”

There are definitely super-smellers, those in the perfume industry, for example, and those in the food and wine industry. Wine tasting, most oenologists will tell you, is 85 percent nose. Their olfactory appraisal involves both the orthonasal route (the schnase) and the retronasal route (the olfactory apparatus in the back of the oral cavity). One of my wine-head friends tells me that after you taste a wine, you can’t scent it full-on again in that sitting. “Do all your nose work first,” he says.

In Somm, the 2012 movie about four apprentice sommoliers preparing to take master exams, an individual lowers his nose to a glass of white wine, inhales, and delivers this bouquet profile: “On the nose this wine is clean, no obvious flaws. This wine has a moderate-plus intensity. This wine is youthful. It’s showing bruised aromas: bruised apple, bruised pear, bruised peach, honeysuckle, chamomile, lavender; (whiff) limestone, wet wool, hay, pistachio, tea.” All that? Really? Lavender and wet wool in the same glass? While I’m skeptical and impatient with winespeak, I am also willing to defer to a good nose. My wife will identify an ingredient in a complex dish immediately. She’ll smell and taste, turn to me, and say confidently and usually correctly, It’s tarragon, obviously. One evening a friend, invited to our house for dinner, brought her prized dessert and invited us to guess her secret ingredient. She stumped me. She stumped my wife. Then our son smelled it and tasted. “Pear,” he said without a moment’s hesitation. Adding, “I hate pear.”

If you asked me, smell chemistry, as it pertains to the production of smells we sell and buy, has been a dismal fail.

For years, in the classroom I was subjected to a dizzying range of scents as I stood at the podium while fragrant students filed in, both men and women, redolent with manufactured odors—shampoos and conditioners, colognes and perfumes, lotions and body washes, deodorants—aggressive smells often applied in profusion, frequently to the point of bringing tears to my eyes. You could classify student scents: candy shop, flower shop, candle store, compost pile, with an occasional blast of ashtray. Smell posed a real occupational challenge. If you asked me, smell chemistry, as it pertains to the production of smells we sell and buy, has been a dismal fail.

And yet progress marches on. Coming soon, I’m sure, to a cell phone near you: digital smell (hand). How long before we can access every imaginable fragrance on iSmell? What a world (sniff). Dude, smell this: it’s bacon!

Scientists have zeroed in on smell at the center of our galaxy. They’re out there looking for amino acids and the origin of life, and in a dust cloud they find ethyl formate, the chemical smell of raspberries. Closer to home, astronauts in orbit say that food has little or no smell, or taste, in the zero gravity zone. And space itself, their noses tell them, when they bring the scent of it in on their space suits, smells like burnt steak, hot metal, or welding fumes.

Imagine life without smell. If I were up there in orbit, feeling earthsick, I might want to open Google Scent (hand) and click on freshly cut grass (sniff) or burning leaves (sniff) or pumpkin pie. Or maybe (sniff) Old Spice.

October 3, 2023

More Than Enough–on walking at 5:00 a.m.

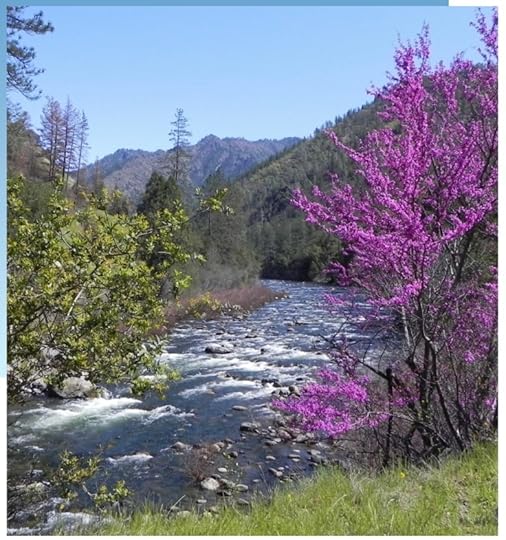

I’ve been thinking about topophilia of late. “One’s mental, emotional, and cognitive ties to a place,” as University of Wisconsin geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, who coined the term, defines it. Where I’ve had this feeling, of being tied to and restored by a place, is just outside my door.

This morning I can’t see much of the place because I’m out in the pre-dawn hours, walking. In a walk around the block that’s not a block, a block that’s bigger than a block (a road sign calls the street Wagon Wheel Lane, but it’s more oval than a circle) in a thirty-minute walk consisting of four laps, I cover a mile and a half. It’s just me and the road, thirty dark houses, the sky, and the shadows.

What is it about walking in the not-quite dark? The sky feels closer, and deeper. This morning there’s a bright full moon in the west. On the east side of the earth, Venus outshines the stars. I carry a small flashlight with me, in case a car or jogger or dog walker comes by, to announce my form, but at this hour I’m all by myself. A mile away, on Telegraph Road, a heavily loaded truck slowly accelerates. I hear an owl in a tall pine close to the road. Otherwise, quiet.

I am temporarily and self-consciously alone.

#

Later today my wife and I will walk together. This time of year we have to walk carefully, because the walnuts are dropping.

We have a short-long walk (five miles) and a long walk (eight miles), in and around and out of the neighborhood. Depending on how we feel or the time of day or the weather, we alternate these two routes. All through June and July, along the short-long route we take note of the walnut trees bearing the best fruit on limbs that are low enough for us to reach. “There’s one,” Tizi says. “Look at those,” I say. And we point up into branches heavy with walnuts, hard green globes, some almost the size of tennis balls.

We tell ourselves we’ll have to remember these spots. Ballantrae Road. Inveray Road. Inkster between Quarton and Lone Pine.

Late July and early August, when the nuts are ready, we come back in the car, stop by the side of the road, and pick 75-100 walnuts for a liqueur our daughter makes. Grain alcohol, split walnuts (including the pungent lime-green jackets), orange peel, cloves, some sugar, and a long infusion period. In six weeks to two months, the mix will turn brown, then black, until it’s time for filtering and bottling. Nocino, the Italians call it. A digestivo.

By the end of September, the rest of the walnuts have softened. They drop from the trees and break open, revealing their ugly black innards. The roads and sidewalks are a smear with these drops. For weeks, where the best trees are, we’ll walk single file, carefully stepping around the inky splotches underfoot.

While we walk with difficulty, we talk. Also with difficulty.

Single file walking was not made for a person hard of hearing. This morning, ten feet ahead of me, Tizi asks me a question.

My answer: “Huh?”

In certain spots along this sidewalk you can hear the thud of falling walnuts. Fat rain. What if I got hit on the head by one?

She repeats the question. I know it’s a question because of the rising intonation at the end of the sentence, but I still didn’t get it.

Since I started thinking about being beaned by a walnut, I’ve been humming to myself, an affliction I enjoy–readily available music in my head. I ask her: “Who sang that song, ‘The raindrops keep falling on my head’?”

She answers, without turning, “Burt Bacharach.” For some reason, I hear and understand this.

“He wrote the song,” I say. “Someone else sang it.”

“Dione Warwick.”

“It was a guy.” I find out later that it was B.J. Thomas. I have to look it up. I think for a second, then start to sing, to the tune of that song, “Black walnuts keep falling on my head.”

“Watch out. Here’s a bad spot,” she says, pointing at a section of sidewalk shaded over with walnut trees, patches of cement stained black. So bad she slows down a little, closing the distance between us.

And I’m still singing: “But that doesn’t mean my hair will soon be turning black…”

I’m sure she would like to change the station. It’s a sappy song, truly. And she’s got it in for Burt Bacharach, whom she thinks of as one of the kings of sap (Neil Diamond, Barry Manilow, she does not cotton to you either.)

It’s warm this morning. She stops, pulls off her jacket and hands it to me. “Hold this,” she says.

I can’t help myself. It’s not heavy, it’s her jacket. I sing this, to the tune of “He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother.” She shakes her head. Whereas I can never have too much music, even music I don’t particularly like, she can. I’m testing her patience.

“Do you have a calorie counter on that thing? That’s what I wanted to know, back there.”

My Fitbit, she means. I can tell her how many steps we’ve walked, and yes, probably how many calories we’ve burned. I’m still learning the device.

Behind me another walnut hits the sidewalk. We carefully resume our steps, and I think: What if I got hit on the head by a walnut and it miraculously restored my hearing? Not just normal hearing. What if it made me a super-auditor? I could hear everything Tizi says, on our walk, in the house. I could hear those two guys working inside that house across Lone Pine road right now, those two women walking in our direction, a quarter mile away. In restaurants, two lovers at a table in the back, whispering to each other.

These things happen–a bump on the head, then miracles–on tv, in the movies, in medical literature. Suddenly this guy knows the square root of any number you give him. Suddenly this woman speaks perfect Portuguese. In medical literature, this phenomenon is called “acquired savant syndrome.” Scientific American calls it “brain gain,” citing the example of a woman who suddenly feels the need to draw triangles, which evolves into accomplished abstract design in the manner of Frieda Khalo and Picasso. A boy hit on the head with a baseball can suddenly compose piano concertos.

Or what if I could suddenly remember everything–the names of all the teachers I ever had, the kids in every class I ever sat in, as a student and as a teacher; all the significant conversations, even the most trivial small talk; the words to every song I ever heard. Right now, on the jukebox that is my brain, Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer” is playing. It’s a song I’ve heard 500 times, and I know only these words: “I am just a poor boy though my story’s seldom told…something or other, something or other, then “In his anger and his pain, I am leaving I am leaving,” something or other, something or other, “…lie lie lie…lie lie lie…”

On the home stretch down Van Ness, Tizi says something like ikle blat.

“Huh?”

Again, ikle blat.

I have to catch up. We’ll stop under a large maple tree where every morning she smells something she can’t put her finger or her nose on. “Do you smell that?” she’ll say. And I’ll say no, no I don’t. In addition to auditory, do I have olfactory deficit? What would a surfeit of smell be like, being a super smeller? Maybe wonderful. Possibly terrible. Any such surfeit could be a curse.

“Broken glass,” she says now. “I wondered if you saw the broken glass back there.”

#

All but four of the thirty houses have yard lights on at 5:00 a.m. It’s a neighborly contribution of light, I know, in the interest of safety. But the moon is more than enough. The shadows of the tall cottonwoods make the road look wet, like giant walnut stains, also like islands or continents that I walk across.

Part of the time out there I’m thinking about green beans and when I ought to get a haircut (soon). Then again, I can’t look up at that sky and not feel something, not be awed by the depth of its emptiness and also by a kind of presence. Back home I consult my Emerson for help, Emerson, who referred to “over-soul,” not god, but something mystical that helps man and woman “weave no longer a spotted life of shreds and patches, but live with a divine unity.” I seriously doubt that I’ll get there, but I’m opening my defective eyes and ears, all my poor senses on these strolls in the dark, looking up in wonder.

October 2, 2023

When Bacco Smiles–from American English, Italian Chocolate

My wife’s old aunt has an omino (the diminutive of uomo, the Italian word for “man”). Omino. Little man. When she wants to cook a rabbit for lunch, she has an omino who sells her the rabbit. She wants fish, she has another omino. She has a repair job to do in the house, she calls a different little man. We were having lunch the other day, a baked orata she got from her fish omino. I asked her about the wine. Dark red, slightly frizzante, in a full liter bottle with a metal cap, no label. She says—of course—she has an omino.

“He lives just over there.” She points a crooked finger toward a hillside. “He’s been bringing us wine for years.”

I want an omino.

In particular, I want a wine omino.

One of the special pleasures of being in Italy is local wine. It’s young, it’s light in alcohol content, it’s great with food. And, by American standards, it’s incredibly cheap.

Consider the carafe—that ubiquitous vessel gracing the trattoria table. There are days we order a quarter liter, or a half liter, or sitting down to eat with a large appetite and the prospect of many luxurious foods, we know we’re going to need a full liter. All the years I brought people to Italy on eating excursions, they inevitably extolled the virtues of the wine. They would say, What is it about these Italian wines? I don’t get tipsy. I can’t get enough of it. And no headache.

For some time now, when I buy wine, I go to Zonzini. It’s a store just down the road from our apartment in San Marino. He is part wholesaler, part retailer, a purveyor of, among other things, bottled water by the case, chocolates, liquor, and wine. The high ceiling and cement floor, along with the floor-to-ceiling metal racks, give the place the feel of a warehouse. Behind the cash register there’s a stock of wines from all over Italy. You can go back there and look. Typically I stand in front of local wines, the ones from Romagna, and select Sangiovese Superiore. My criteria for selection are attractive label and price. The wines come from nearby towns, Imola, Predappio, Cesena, Bertinoro, San Patrignano. Until recently, I had my standards. I would not go lower than 5 euros for a bottle.

That was then.

Alas, Bacco has smiled upon me.

I have an omino. Her name is Francesca.

Okay, so she’s not a little man. And technically she’s not really an omino because she works in a store. Your standard issue omino does not have a website; he has a farm. But I’ll take her.

Across from the mercato centrale down in Rimini, a sprawling fish-meat-vegetable-fruit market, I notice this store one day: I Vini delle terre di Malatesta. It’s well lit. It looks like a high-end enoteca. Lots of racks, lots of bottles with attractive labels. Except in the back corner, I notice two faux kegs protruding from the walls. On each keg two spigots. Three reds, one white. For each wine there is information about its source, alcohol content, and price. This store sells vino sfuso, the stuff you get in trattorie by the carafe.

“Bring your own bottles to the store,” Francesca explains, “or we have bottles you can buy, and fill, and reuse. Buy as much as you want.”

I taste the two reds, a Cabernet and a Sangiovese, and choose the latter. She fills a handsome bottle, packs it in a thick take-it-with-you sack. All for 3 euro. In the U.S., the sack alone would cost that much. I take the wine home and love it.

In fifty years Italian wines have come a long way. In the American consumer’s view, such as it was, Italian wine was kind of a joke. Buy a straw-covered Chianti fiasco, pour out the wine, and plug up the bottle with a candle. It was like Mateus. Great bottle. The wine? Meh. Then again, fifty years ago, Americans were not wine drinkers. And the Italians were smart, my wife likes to say. They kept the good wines for themselves. No doubt that’s part of the story. So many omini, so much good local wine.

Then along comes Giovanni Mariani, Jr., son of Giovanni Mariani, Sr. The latter founded the House of Banfi, in Greenwich Village, in 1919. Mariani the younger introduced Lambrusco to the American consumer in 1969, sold 20,000 cases of the stuff that year, then 50,000 cases the next year. By 1975 imports of the bubbly sweet red increased to 1.2 million cases, in 1984, a whopping 11.2 million cases. Lambrusco is a wine you drink cold, a forerunner of that unfortunate American contribution to wine culture, the wine cooler. (I remember, in the mid 70’s, a night out in Columbus, Ohio, with a couple friends, cruising bluegrass bars, guzzling Black Russians, and finishing the night drinking Riunite, on the rocks.) Riunite and Cella wines established the Italian footprint, or wine stain, in the American market. According to Funding Universe, “By 1980 Banfi alone was bringing more wine into the US from Italy–some nine million cases a year–than France and Germany combined.”

Thanks for that sweet red wine, Banfi, we might say. The wine was pretty bad. But there’s more to the story. One word:

Brunello.

In 1977 the Banfi organization charged oenologist Ezio Rivella with finding the perfect location in Italy for a vineyard. He was their omino. He did his job. The place he found was Montalcino.

Today a Brunello di Montalcino will sell for up to $250 a bottle. American wineheads flock to that far flung Tuscan town. Rory Carroll, writing for The Guardian, reports, “Those who get to taste [Brunello] come away drooling adjectives such as intense, full-bodied, fruity, smooth, rich, chewy, velvety, super-ripe, spicy, gigantic. In the battle with the new world, Montalcino stands as a citadel of old world might and venerability.”

And today, Coldiretti, an Italian grower-producer organization, boasts that Italy is the largest wine exporter in the world. In 2013, the U.S. imported $1.3 billion in Italian wines.

In omini we trust.

Probably every trattoria and osteria in Italy has an omino. He’s the proprietor’s cousin or uncle, he’s a farmer with some vines who makes local swill that’s dirt cheap and consistently good. The omino’s vino sfuso graces the table, complements the food, goes down easy.

Except when it doesn’t.

In Novilara, in the hills above the Adriatic, is a restaurant where we eat tagliatelle and beans. The food is something of a religious experience; the house wine, on the other hand, for two of three consecutive years was terrible. It was kind of a joke. But not.

And just last week my wife and I had lunch in a Pesaro trattoria. At the table next to us a couple local guys ordered wine by the glass. The server did not stand on ceremony. He didn’t show the label or smell the cork or linger and watch as the guys swirled, sniffed, and sipped. This was a joint. He brought them stem glasses, the wine already poured, then he brought them their food. I confess at the moment I felt just a little smug. We ordered the house wine. Don’t they know how good it is, how simple and delicious in bistro glasses? When the server came to our table and set down a half liter carafe of red, I turned over my bistro glass, poured some wine, and had a taste. Someone’s uncle must have had a very bad year.

Then there’s Fabio, our new friend. A couple nights ago we had dinner at a local agriturismo that serves strozzopreti with sangiovese, sausage, and radicchio, a dish of pasta that is life changing. And the wine was exceptional.

“It’s a sangiovese,” Fabio said, “with a little merlot added. You can taste the merlot—it makes the wine a little rounder.”

I wasn’t really sure I could taste it, but I nodded my head.

He said this year the grape harvest was not very good. They didn’t make wine.

“If you don’t have good grapes,” he said, “you can’t make good wine.”

They still had a lot of wine from the year before, enough to get them through the year. We could buy some if we wanted to; a bottle, a five liter jug, as much as we wanted.

In omini we trust.

Trust, yes. But verify.

October 1, 2023

On Wine Tasting and the Limits of Winespeak–from Get Thee to a Bakery

“You taste wine the same way I do,” the guy pouring says. “We all have the same equipment: nose, mouth, tongue, palate.

Technically, yes. And it’s very nice of him to say that.

It’s my last day in Sonoma. I’ve had a head cold all week, so none of my “equipment” has been working very well. Thus far I’ve had only a few sips of wine with lunches and dinners. This afternoon I’ve decided to visit some tasting rooms, to open my mouth and let the wine in. There are over 425 wineries in Sonoma County, 15 or so within a few miles of where I’m staying. This one is known for its chardonnays and pinots.

I’ve just tasted the third of three pinot noirs the winery is pouring today, and listened, amazed, to the wine guy’s description of the wine, a brief disquisition on its body (medium), its structure (supple), acidity (tangy) fruit (cherry pie) spice (an allspice matrix!) barrel time (old French oak) tannins (pliable) and finish (persistent).

“I don’t taste cherry,” I say.

Nor do I detect structure. I understand tannin but I don’t get pliable. I tell him my mouth is dumb. I’m just not a very good taster.

He asks, “Did you like it?”

“Yes, I did,” I say, and empty my glass into the spittoon. On a scale of 0-3, 0 being never again, 3 being bring it on, I’d give this wine a 2.

These wines probably have Parker points and Wine Spectator ratings, both of which use a 100 point scale. Suppose the third wine is a 92. I wonder: What would make it a 91? A little less pliability? Or a 93? A slightly larger slice of cherry pie? This may be an example of effing in ineffable. How do you quantify a qualitative judgment?

Eons ago, as an undergraduate in a survey of 20th century British literature, I wrote a midterm essay in response to this assignment:

“Referring to at least two of the authors we’ve read in the course thus far, analyze the nature of metaphor in modern literature. What, specifically, are the metaphors in, say, Conrad and Yeats? If the metaphors are vehicles for their ideas, what are the limits of metaphoric expression?”

Fortunately, or maybe unfortunately, it was a take-home test. Over the weekend I thought hard about “the nature of metaphor in modern literature,” thought about it until my head hurt. I poured over a handful of Yeats poems, with helpful annotations I had made, like these– Cycle of time. A vision of hope. Mutability of experience. The body. I re-read my marginal notes on Heart of Darkness– Knitters of fate. Categories of defense. The failure of language. Existential challenge—all the while trying to figure out exactly what “the limits of metaphoric expression” might mean. I wrote, I returned to my notes and annotations, I revised and gradually stopped writing. My essay had a long finish.

Next class I handed in three closely written pages and waited a week for the professor to return my work. When I got it back, I found a few phrases of my essay underlined, a few phrases double underlined, along with an occasional question mark and few trenchant exclamation marks in the margin. Flipping to the last page, as we all do, I looked for the grade. It was an 87. I knew what that meant, a B. Okay, but 87? How had he arrived at that specific number, and not, let’s say, 86 or 88. Those underlines and double underlines, did they add to or subtract from 100? What could I have done, what exactly was he looking for that would have made my essay an 89 or 90? I suspect he might not have been able to explain how he arrived at 87 or what I could do to raise that number to 88 or 90, beyond telling me something like be smarter, make better connections.

A few years later, as a young teacher, I filled a gradebook every semester with marks (I decided on A through E) for 22 students in each of the five classes I taught. Homework, quizzes, exercises, essays, midterms, finals. At semester’s end, for each student, I would see something like this: C, A, B-, B+, B-, D, E, A-, A-, C+, C+, C, B+, A-, E, E, B, B, B. To arrive at a final grade, I laid a ruler across each row of marks, tracking student performance left to right, across fifteen weeks, and on the far right rendered my final judgment: B. Sometimes upon further reflection, I affixed a minus or a plus to that letter. Never quite sure, except in my bones or in my heart or vaguely (very vaguely) in my head, if that grade with its plus or minus was a true value summarizing those letter grades.

This was long before the advent of spreadsheets and grading technologies, before primary trait analysis. And I’m pretty sure this grading practice was widespread: impressionistic, holistic, supported mainly by the authority the individual who rendered the judgment. It was an 87 or a B+ because a full professor said it was. Nuff said. Much like a pinot is a 92 because Robert Parker or Wine Spectator say it is.

Words help. They name qualities, characteristics. Words and categories enable dissection, which enables analysis and evaluation. The problem is, some things are easier to dissect than others.

I’ve been reading Walter Isaacson’s biography of Leonardo da Vinci. Thanks to Isaacson’s helpful descriptions of the great artist’s paintings, I now look for Leonardo’s use of shadow and “sfumatura,” for the characteristic depictions of water and hair and landscapes in his paintings. I imagine I see left-handed brushstrokes. Knowing something about Leonardo’s work helps me see the painting of other artists at the time differently. Huh, I might think, look at that pile of rocks. Did the artist even bother looking at nature the way Leonardo did?

As an undergraduate, even farther back than “the limits of metaphor,” I took a music appreciation class. I must have listened to Mozart’s Symphony #40 a hundred times. That symphony and that recording, by Sir Georg Solti directing the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, established my frame of reference. I’ve been startled by other recordings of that symphony I’ve heard since, by how fast the first movement runs, by the chug and lurch of another director’s minuet movement. I’ve listened to other symphonies with, well, enhanced appreciation, noticing how the second movement in #40 compares to the second movement in Mozart’s #41 or, because of repeated, careful listening, how it compares to the amazing, mournful second movement in Beethoven’s 7th.

But seeing, listening, and tasting are not equal.

Seeing and listening lend themselves more readily to dissection and appreciation than tasting. A Leonardo just sits there, on the wall or on a page or a screen. Pull back from the artwork, or move in close, or alter the angle of your viewpoint. You can take a very long look. It’s a freeze-frame experience. Likewise, in music: rewind, replay, revisit the same performance, the same shift to a major key, the swelling of sound, the crescendo. Listen, take it in. Looking carefully, listening intently, you can make the experience last as long as you like.

A taste, on the other hand, is brief, intense, and evanescent; a couple sips and it’s finished. When you look and listen, you may get tired, but you don’t get full. Or drunk. And what about memory? Are memories of what you see (a sunset, a face, a painting) and what you hear (a bird call, a child’s laugh, a piece of music) more retraceable and detailed and vivid than memories of a gustatory experience?

There are super tasters, I know, sipping savants in the wine world, people endowed with if not supernatural equipment then with highly discriminating taste and deep stores of palate memory. I bow to them. To communicate with us, they deploy a special language. They say things like this about wine:

“Already revealing some pink and amber at the edge, the color is surprisingly evolved for a wine from this vintage. However, that’s deceptive–as the aromatics offer incredible aromas of dried flowers, beef blood, spice, figs, sweet black currants and kirsch, smoked game, lavender, and sweaty but attractive saddle leather-like notes. Full-bodied and massively endowed, with abundant silky tannins, it possesses the balance to age for 30+ years” (Robert Parker, on a 2001 Chateauneuf du Pape).

This is a pronouncement handed down from on high. It makes me want to taste the wine, but only after I’ve whiffed some beef blood and licked a sweaty saddle.

What sets the apprentice taster apart from the journeyman is years of experience and control of the language. Years ago a friend took me to his wine club dinner. A dozen men descended upon a restaurant (oh, yes, all men). Serious guys, they each brought their own box of Riedel glasses. It was an evening of blind tasting, eight wines chosen to accompany a nice dinner.

For 2-3 hours, we tasted wines in pairs and talked about them. Two Amarone, for example, one a 2003, the other a 1999. I was given a notepad and pencil. After the pours we swirled and sniffed, we sipped and deliberated. Then we went around the table and described the wines and our tasting experiences. Compared to these guys, I was still in short pants. “Full bodied,” I could say. “Nice color.” But they would have at it, making little speeches, practicing the lingo, somming it up. I went to three of these dinners. Every night I finished at the bottom of my class. And every night, the same two guys identified all the wines correctly. When they talked, I took notes. The older wines were tight. Some wines’ tannins were grippy. They talked, but they didn’t revel in winespeak.

Those nights I was reminded of graduate seminars I attended in which students, me for example, practiced speaking litcrit, making statements like this: “Deconstructionists have to be aware of the text’s shifts or breaks that may eventually create instabilities in attitude and meaning. At the verbal level, a close reading of the text will highlight its paradoxes and contradictions, a reading against the grain, in order to reveal how the ‘signifiers’ may clash with the ‘signifieds.’”

Right. I am not ashamed to say I have no idea what that means. To me it’s a black hole.

Words help, in wine tasting, in the consumption of literature. They can explain the 87 and 92. They also can get in the way. The cabernet, the novel, did you like it? Yes. Do you want to more? Yes.

To most consumers, that’s enough.

September 17, 2023

Hang Up–taking my tech for a walk

There’s a guy coming down the hill on Sodon Lake Road. Tizi and I are walking up the hill, twenty minutes into our morning route. He’s wearing hiking shorts and walking shoes. So: we’re on the same page, out walking for our own good.

He takes the opposite shoulder of the road and we pass each other. As we do so, these words occur to me. They rise unbidden: “Hail, neighbor. And well met.” One of the benefits of having read Shakespeare, odd salutations.

I say it, but not very loud. More for my benefit than his. He wouldn’t have heard me anyway. I can see by his earbuds he’s in two places at once.

Tizi says, “For heaven’s sake, don’t say that.”

It’s early enough, I tell her, I could have said Good morrow to you, sirrah.

Everyone we pass is connected. Later, when we reach Long Lake Road, we’ll see a guy walking up the sidewalk, holding his cell phone in front of him, at chin level. Is he talking to someone? Is he filming his walk? Good God, is he watching television as he walks?

Welcome to the devicification of modern life.

I can’t talk. I have a phone in my pocket. I’ll check it before we reach the end of Sodon Lake Road, look at the time, see if I have any messages. (One of our grandsons just had a few teeth pulled.) And I’ve recently become even more devicified. I’m wearing a Fitbit again. With some accuracy it counts my steps. With less accuracy it monitors my sleep phases: light, REM, deep. I don’t need Fitbit to tell me I slept well or poorly. (The last two nights it has both under- and over-reported duration, and in both cases rated my sleep “fair,” whereas I would have rated it “good”). But I like the step counter and especially the little vibration it emits on my wrist 10 minutes before the hour. That vibe is a reminder: get up and move.

“Which way to the lake, I wonder.” I say this to the back of Tizi’s head.

If she heard me, she’s ignoring the question. We’ve walked this route fifty, if not a hundred times, and we have never seen Sodon Lake. I tell her it must not be much of a lake. “Pond, more likely,” I say. At the top of the hill, behind the next five or six houses, the land slopes down. “Maybe it’s down there in that gully,” I say. When does a pond become a lake?

“I hope Scout is out,” she says.

Scout the dog, a young collie. A lassie she loves.

I address the back of her head: “When does a pond become a lake What do you think?”

“I love Scout,” she says.

Out west of the town where I grew up, we had Wagner’s Pond. No one would have thought of calling it a lake. Behind the house where we live, there is a Walden Pond. Same. It’s a lake to no one. I’d bet money that Sodon Lake is no bigger than Walden Pond. But Long Lake, which the next road is named for, and which is also nowhere in sight, it’s a legitimate lake. I’ve driven past it. I’m sure everyone living next to it is happy it’s not called Long Pond.

Wherever we go, we meet these device-enchanced walkers. In truth, if I were alone, just me and my Fitbit out for a walk this morning, I would probably also be further connected to my device. I’d be blue-toothing music. Right now, on a 30 second loop that’s been earworming me for half a mile, I’ve been humming, circa 1966, the Knickerbockers’ song “Lies!” I would be singing it, but I only remember a few words of the song, Lies! That’s all I ever get from you. If I had earbuds I could listen to it on my phone.

“Hail, neighbor” reminds me of how our son answered the phone when he was in middle school. Every caller he would salute by saying, “Hey, what’s up, dog?” (Hail, dog, well called.) One night Tizi said to me, across the kitchen table, “Who’s Doug?”

Those were landline days. In the American home there was one centrally located phone that everyone used (ours was in the kitchen), the home phone, vestiges of which are still visible on registration forms you fill out. Ian Bogost, writing for the Atlantic, recently lamented the end of the landline. It had its uses. A child home alone, assuming she did not have a cell phone, could be taught to call 911 in case of an emergency. The landline was “unlocked.” On a landline, Bogost notes, “Everyone might have to talk to grandma, depending on who picked up.” Or a neighbor. Or the plumber–“I’ll be there in ten minutes.”

Nowadays, post-landline, what do we do about the undeviced family member? Before she went digital (finally) and got deviced, if I went to the grocery store and needed to ask my wife a question, she was unreachable. I was very close to her on the grid, like a mile away, but she was definitively off it.

In the house I grew up in, there was one phone, a Northern Electric black rotary phone. Telephones back then were like Model T’s. They came in any color you wanted, as long as that color was black. The phone was made of hard rubber, plastic, and metal, and weighed more than 5 pounds. On the rotary dial there were letters visible, enabling you to indicate the switching system, called the “exchange,” that your line was connected to. Our town’s exchange was Oxbow. The first telephone number I memorized was OX 59111. Yes, back then you remembered telephone numbers. You kept your list of “contacts” in your head. Some of them are still there. Danny Leman was 59103, Ronnie Fritz was 59303, Jeff Schilling was 56431, Dean Gaul was 59633.

Innovations came along. The heavy desk phone gave way to the wall phone. Then came the “trimline” and the “princess.” Rotary dial, a quaint technology that took forever to enter a telephone number, gave way to digital keys. (I remember my children marveling at how slow it was when they dialed their grandparents’ old phone, a trimline with rotary.) For a telephone line you paid Ma Bell. Compared to today’s prices, it was cheap–in the extreme.

This was before “voicemail,” an awful term we would never have suffered if it weren’t for the advent of email. In the front room of our house, my father’s office, the location of our home phone, he had a machine he called “the recorder” that he switched on when he was out of the house. “Hello, this is John H. Bailey . . . “ It was the size of a microwave oven. As late as the mid-70’s, college friends of mine who went off to New York to become actors all had an answering service they would call to collect messages. Then came voicemail.

Those good old days, however, became the bad old days. The landline phone began to ring–all the time. Every night when we sat down to dinner, it rang and rang and rang. You picked up the phone to shut it up. On the other end, solicitors. “Hi, Mr. Bailey, I was wondering if you would be interested in virus protection for your computer.” “Hi, Mr. Bailey, the governor needs your financial support in his re-election campaign.” Some callers, total strangers, acted like we were soon to be good buddies. “Is this Richard?” “Is this Tiziana?”

I had a cellphone by then. As did our son and daughter. We said goodbye to the landline.

“You’ve got mail!” The AOL guy said it with such enthusiasm. And at first that enthusiasm was infectious–I’ve got mail!–until it wasn’t. These days, with AOL a distant memory, one of my morning rituals is deleting email, anywhere from 30 to 50 messages a day (all those calls at the dinner hour). Like most people, I also screen calls. If the number isn’t in my address book, associated with a name I know, I usually kill the ring and let the call go to voicemail. Pew Research reports that Americans answer only 19 percent of unknown calls on their phones. The average American looks at her digital device 144 times a day. Peter Frost, a psych professor at Southern New Hampshire University, says that young adults use their device 5 ½ hours a day. Given stats like these, can digital detox be far behind? If not that, mental meltdown.

Experts in “sleep ecology” say no screens an hour before you go to bed. And no devices in the bedroom. This morning at 4:30 a.m., lying awake, I saw the giant screen on Tizi’s iPad light up on her night table. The visual equivalent of “you’ve got mail.” The other day I read about a “digital well-being” setting on my iPhone, which I couldn’t find when I tried. To get digital well-being, I guess I need an upgrade. A new digital setting to treat my my digital device dependence. Methadone comes to mind.

This morning Fitbit tells me I walked an average of 93,914 steps a day last week. I slept an average of 5 hours and 50 minutes a night. For a while I will continue to track this data and find it useful, but really, the app is just a digital bauble. When we walk for two hours, up and down some hills, past walkers and dogs, past lakes and ponds, I know I’ve exercised. When I wake up at 4:00 am, having gone to bed at 11:30 pm, I know I’m going to sluggish later in the day.

“Bring your phone,” Tizi says before we leave the house to walk. Because what if the kids call?

“Bring your phone,” she says when I go out for a walk by myself.

Implores me. Because what if something happens? I might trip and fall and knock myself unconscious and be found lying by the side of the road, found by a digital walker who would call for help. Who is this guy? the walker might wonder, and finding my device in my pocket, touch the screen, waking it up. “Press home to open.” Then, “Touch ID or Enter Password.” Oh well.

“Yes, 911, there’s some guy lying by the side of Sodon Lake Road. Can you help?”

aging casalinga church climate coffee covid death excerpt Fano fasting Florence food friendship greens health hiking identity in-house language Marches marriage mistra music on the menu pasta Pesaro reading recipe restaurant Rimini Romagna Rome San Marino school screencast seafood tech the dead the long drive travel Tuscany Venice wine writing youth

Hang Up

There’s a guy coming down the hill on Sodon Lake Road. Tizi and I are walking up the hill, twenty minutes into our morning route. He’s wearing hiking shorts and walking shoes. So: we’re on the same page, out walking for our own good.

He takes the opposite shoulder of the road and we pass each other. As we do so, these words occur to me. They rise unbidden: “Hail, neighbor. And well met.” One of the benefits of having read Shakespeare, odd salutations.

I say it, but not very loud. More for my benefit than his. He wouldn’t have heard me anyway. I can see by his earbuds he’s in two places at once.

Tizi says, “For heaven’s sake, don’t say that.”

It’s early enough, I tell her, I could have said Good morrow to you, sirrah.

Everyone we pass is connected. Later, when we reach Long Lake Road, we’ll see a guy walking up the sidewalk, holding his cell phone in front of him, at chin level. Is he talking to someone? Is he filming his walk? Good God, is he watching television as he walks?

Welcome to the devicification of modern life.

I can’t talk. I have a phone in my pocket. I’ll check it before we reach the end of Sodon Lake Road, look at the time, see if I have any messages. (One of our grandsons just had a few teeth pulled.) And I’ve recently become even more devicified. I’m wearing a Fitbit again. With some accuracy it counts my steps. With less accuracy it monitors my sleep phases: light, REM, deep. I don’t need Fitbit to tell me I slept well or poorly. (The last two nights it has both under- and over-reported duration, and in both cases rated my sleep “fair,” whereas I would have rated it “good”). But I like the step counter and especially the little vibration it emits on my wrist 10 minutes before the hour. That vibe is a reminder: get up and move.

“Which way to the lake, I wonder.” I say this to the back of Tizi’s head.

If she heard me, she’s ignoring the question. We’ve walked this route fifty, if not a hundred times, and we have never seen Sodon Lake. I tell her it must not be much of a lake. “Pond, more likely,” I say. At the top of the hill, behind the next five or six houses, the land slopes down. “Maybe it’s down there in that gully,” I say. When does a pond become a lake?

“I hope Scout is out,” she says.

Scout the dog, a young collie. A lassie she loves.

I address the back of her head: “When does a pond become a lake What do you think?”

“I love Scout,” she says.

Out west of the town where I grew up, we had Wagner’s Pond. No one would have thought of calling it a lake. Behind the house where we live, there is a Walden Pond. Same. It’s a lake to no one. I’d bet money that Sodon Lake is no bigger than Walden Pond. But Long Lake, which the next road is named for, and which is also nowhere in sight, it’s a legitimate lake. I’ve driven past it. I’m sure everyone living next to it is happy it’s not called Long Pond.

Wherever we go, we meet these device-enchanced walkers. In truth, if I were alone, just me and my Fitbit out for a walk this morning, I would probably also be further connected to my device. I’d be blue-toothing music. Right now, on a 30 second loop that’s been earworming me for half a mile, I’ve been humming, circa 1966, the Knickerbockers’ song “Lies!” I would be singing it, but I only remember a few words of the song, Lies! That’s all I ever get from you. If I had earbuds I could listen to it on my phone.

“Hail, neighbor” reminds me of how our son answered the phone when he was in middle school. Every caller he would salute by saying, “Hey, what’s up, dog?” (Hail, dog, well called.) One night Tizi said to me, across the kitchen table, “Who’s Doug?”

Those were landline days. In the American home there was one centrally located phone that everyone used (ours was in the kitchen), the home phone, vestiges of which are still visible on registration forms you fill out. Ian Bogost, writing for the Atlantic, recently lamented the end of the landline. It had its uses. A child home alone, assuming she did not have a cell phone, could be taught to call 911 in case of an emergency. The landline was “unlocked.” On a landline, Bogost notes, “Everyone might have to talk to grandma, depending on who picked up.” Or a neighbor. Or the plumber–“I’ll be there in ten minutes.”

Nowadays, post-landline, what do we do about the undeviced family member? Before she went digital (finally) and got deviced, if I went to the grocery store and needed to ask my wife a question, she was unreachable. I was very close to her on the grid, like a mile away, but she was definitively off it.

In the house I grew up in, there was one phone, a Northern Electric black rotary phone. Telephones back then were like Model T’s. They came in any color you wanted, as long as that color was black. The phone was made of hard rubber, plastic, and metal, and weighed more than 5 pounds. On the rotary dial there were letters visible, enabling you to indicate the switching system, called the “exchange,” that your line was connected to. Our town’s exchange was Oxbow. The first telephone number I memorized was OX 59111. Yes, back then you remembered telephone numbers. You kept your list of “contacts” in your head. Some of them are still there. Danny Leman was 59103, Ronnie Fritz was 59303, Jeff Schilling was 56431, Dean Gaul was 59633.

Innovations came along. The heavy desk phone gave way to the wall phone. Then came the “trimline” and the “princess.” Rotary dial, a quaint technology that took forever to enter a telephone number, gave way to digital keys. (I remember my children marveling at how slow it was when they dialed their grandparents’ old phone, a trimline with rotary.) For a telephone line you paid Ma Bell. Compared to today’s prices, it was cheap–in the extreme.

This was before “voicemail,” an awful term we would never have suffered if it weren’t for the advent of email. In the front room of our house, my father’s office, the location of our home phone, he had a machine he called “the recorder” that he switched on when he was out of the house. “Hello, this is John H. Bailey . . . “ It was the size of a microwave oven. As late as the mid-70’s, college friends of mine who went off to New York to become actors all had an answering service they would call to collect messages.

Those good old days, however, became the bad old days. The landline phone began to ring–all the time. Every night when we sat down to dinner, it rang, and rang, and rang. You picked up the phone to shut it up. On the other end, solicitors. “Hi, Mr. Bailey, I was wondering if you would be interested in virus protection for your computer.” “Hi, Mr. Bailey, the governor needs your financial support in his re-election campaign.” Some callers, total strangers, acted like old buddies. “Is this Richard?” “Is this Tiziana?”

I had a cellphone by then. As did our son and daughter. We said goodbye to the landline.

“You’ve got mail!” The AOL guy said it with such enthusiasm. An d at first that enthusiasm was infectious–I’ve got mail!–until it wasn’t. These days, with AOL a distant memory, one of my morning rituals is deleting email, anywhere from 30 to 50 messages a day. Like most people, I also screen calls. If the number isn’t in my address book, associated with a name I know, I usually kill the ring and let the call go. Pew Research reports that Americans answer only 19 percent of unknown calls on their phones. The average American looks at her digital device 144 times a day. Peter Frost, a psych professor at Southern New Hampshire University, says that young adults use their device 5 ½ hours a day. Given stats like these, can digital detox be far behind? If not that, mental meltdown.

Experts in “sleep ecology” say no screens an hour before you go to bed. And no devices in the bedroom. This morning at 4:30 a.m., lying awake, I saw the giant screen on Tizi’s iPad light up on her night table. The visual equivalent of “you’ve got mail.” The other day I read about a “digital well-being” setting on my iPhone, which I couldn’t find when I tried. To get digital well-being, I guess I need an upgrade. A new digital setting to treat my addiction to my digital device. Methadone comes to mind.

This morning Fitbit tells me I walked an average of 93,914 steps a day last week. I slept an average of 5 hours and 50 minutes a night. For a while I will continue to track this data and find it useful, but really, the app is just a digital bauble. When we walk for two hours, up and down some hills, past walkers and dogs, lakes and ponds, I know I’ve exercised. When I wake up at 4:00 am, having gone to bed at 11:30 pm, I know I’m going to sluggish later in the day.

“Bring your phone,” Tizi says before we leave the house to walk. Because what if the kids call?

“Bring your phone,” she says when I go out for a walk by myself.

Implores me. Because what if something happens? I might trip and fall and knock myself unconscious and be found lying by the side of the road, found by a digital walker who would call for help. Who is this guy? the walker might wonder, and finding my device in my pocket, touch the screen, waking it up. “Press home to open.” Then, “Touch ID or Enter Password.”

“Yes, 911, there’s some guy lying by the side of Sodon Lake Road. Can you help?”

September 5, 2023

Bag Man–the things I carry

We heard animals last night, yipping and howling in the woods across the road from the orchard. It was not a sound we are acquainted with.

“Coyotes?” Tizi said.

“They sound like dogs,” I said.

Coyotes, David confirmed the next morning.

They’re out there. The next day, driving over to the Sportsman’s Cafe for breakfast, we saw one loping across a dry grassy meadow along Triangle Road, like it owned the land. Just like it belonged there. Which, of course, it does. It’s wild out here. The other day at the tasting room, a guy described the trouble he’s been having with a brown bear. A big brute he said. Not quite grizzly size, but big. It comes scratching at the front door. The dogs, he said, annoy it, shoo it away. If need be, he said, he can take care of it. Pests like these—coyotes and bears, not to mention pests of the two-legged variety—are another reason people around here arm themselves. Many of them, I suspect, carry.

That morning I couldn’t help but notice I was the only guy in the restaurant openly carrying—a man bag. Anywhere I go, I don’t quite feel normal without it slung over my shoulder. The way those guys—and probably some of the women—don’t quite feel normal without their guns. In this place, I am an oddity.

In some contexts, virtually everywhere I’ve been out here, a man bag can feel downright unmanly. I feel so urban toting it, kind of metro-sexual. In my bag I carry my wallet, a cell phone, a ballpoint pen, a pair of glasses, a couple plastic toothpicks, nail clippers and an Emory board (so necessary since I stopped biting my nails), and two sturdy plastic bags from a local grocery store back home for bagging groceries when I shop, wherever I shop, for lunch.

My son calls my bag a murse. In some circles they say mote (a man’s tote bag). Shops selling them say messenger bag or mail bag.. I wear mine cross-body, like a bandolier ammunition belt. The way Indiana Jones, a gun-toting manly man, wears his man bag.

I can imagine Indie growling, “It’s not a man bag! It’s a satchel.” The term is unfortunate. Simon Chilvers writes in the Financial Times, “The term ‘man bag’ is arguably one of the most irritating in fashion history: ugly sounding, borderline patronising, borderline sexist.”

“It’s not a purse. It’s european.” So says Jerry Seinfeld in “The Reverse Peephole” episode. To which George Costanza says, “A man carries a wallet” (George’s emphasis).

I carried a wallet for years, in my hip pocket, like most American men. At some point Tizi commented on my pants, how the fabric was worn thin on my hip pocket. “And doesn’t that blob back there bother you, sitting on it?” she asked me once. I hadn’t thought about it. But now that she mentioned it, Yes it did.

So I emptied my pockets. And I’ve never gone back.

A cursory study of the etymology of “wallet” suggests the accessory used to be a man bag. A reliable unnamed source indicates: “The origin of the word wallet can be traced back from the ancient Greek word Kibisis which was the word used to describe the sack carried by the God Hermes.” That sounds like a stretch to me, but if it’s okay for Hermes, it’s okay for me. An online etymology dictionary I consult suggests wallet comes into English in the 14th century, from Old French “walet,” a term denoting “knapsack,” or from Proto-Germanic “wall,” a word for “roll.” Or possibly from the old French “golette,” for “little snout,” which I do not understand but immediately love. The point being that a wallet used to be a bag. A man bag.

Bags were necessary because the pocket had not yet been invented. Think of it: life with pockets. In Hannah Carlson’s delightful World’s Use of Pockets: Men’s Clothes Full of Them, While Women Have but Few . . . Civilization Demands Them, she notes: “For centuries, how you wore your purse distinguished masculine from feminine dress, but the purse itself did not belong to a single gender.” But in the 15th century, along come pockets, primarily on men’s clothing, signaling, for centuries, the end of the man bag. On men’s clothing, pockets. In which they keep their stuff. When I was a kid, I was frequently made aware of my father’s presence by the coins (he called them “silver”) or car keys jingling in his pocket. He kept a wallet, which he called a billfold (my Italian father-in-law called his a portafoglio) in his hip pocket. In my mother’s case, I recall her reaching into a apron pocket for a tissue, but otherwise, in my memory she is more or less pocketless.

Pants pockets gave, and continue to give, boys and men a place to put their hands. Hands in pockets can give a man a casual, stylish, insouciant look. But there was and is a downside. In 18th century satirical engravings, hands in pockets indicated lechery. When I reached a certain age my father would say, “Don’t stand around with your hands in your pockets, looking idle.”

With the advent of pockets, pick-pocketing became a thing. I was on a crowded bus in Florence a few years ago with a group. A guy I was traveling with advised me and the members of our group to keep our hands in our pockets to protect ourselves from thieves. By the time we got to Fiesole, this poor guy had been fleeced.

I wear my bag slung across my chest, bag left. In an emergency I can reach into it with my left hand and grab my nail clippers. I was pleased to note recently that’s how Indiana Jones wears his bag, bag left. We are men of inaction and action. Now that I think of it, in all the Jones movies, which I love, I have never seen Indie open his man bag and take something out, ammunition for his pistol, let’s say, or a hankie. Well, he knows what it’s for. And I know what mine is for.

A few years ago I guy came to our house to do some work. Tizi chatted him up. She needed a name. I think she was looking for a blacksmith.

“I know one,” the guy said. “I got his name and number right here.”

He reached around to his hip pocket and hauled out his wallet. Folded in half, it was fat as a deli sandwich. He regarded it with pride, held it out for us to admire. Yes, it was certainly big. Then he opened it, fluttered through a stack of bills and business cards and papers and receipts and photographs, and eventually pulled out a thin slip with a name and phone number written in faded, slightly smeared blue ink.

“My whole life is in here,” he said. He closed his fat wallet and, with an adoring smile, held it out again (again!) for us to admire. When he shoved it back in place in his hip pocket, I wondered how he could even walk straight.

Bag Man

We heard animals last night, yipping and howling in the woods across the road from the orchard. It was not a sound we are acquainted with.

“Coyotes?” Tizi said.

“They sound like dogs,” I said.

Coyotes, David confirmed the next morning.

They’re out there. The next day, driving over to the Sportsman’s Cafe for breakfast, we saw one loping across a dry grassy meadow along Triangle Road, like it owned the land. Just like it belonged there. Which of course it does. It’s wild out here. The other day at the tasting room, a guy described the trouble he’s been having with a brown bear. A big brute he said. Not quite grizzly size, but big. It comes scratching at the front door. The dogs, he said, annoy it, shoo it away. If need be, he said, he can take care of it. Pests like these—coyotes and bears, not to mention pests of the two-legged variety—are another reason people around here arm themselves. Many of them, I suspect, carry.

That morning I couldn’t help but notice I was the only guy in the restaurant openly carrying—a man bag. Anywhere I go, I don’t quite feel normal without it slung over my shoulder. The way those guys—and probably some of the women—don’t quite feel normal without their guns. In this place, I am an oddity.

In some contexts, virtually everywhere I’ve been out here, a man bag can feel downright unmanly. I feel so urban toting it, kind of metro-sexual. In my bag I carry my wallet, a cell phone, a ballpoint pen, a pair of glasses, a couple plastic toothpicks, nail clippers and an Emory board (so necessary since I stopped biting my nails), and two sturdy plastic bags from a local grocery store back home for bagging groceries when I shop, wherever I shop, for lunch.

My son calls my bag a murse. In some circles they say mote (a man’s tote bag). Shops selling them say messenger bag or mail bag.. I wear mine cross-body, like a bandolier ammunition belt. The way Indiana Jones, a gun-toting manly man, wears his man bag.

I can imagine Indie growling, “It’s not a man bag! It’s a satchel.” The term is unfortunate. Simon Chilvers writes in the Financial Times, “The term ‘man bag’ is arguably one of the most irritating in fashion history: ugly sounding, borderline patronising, borderline sexist.”

“It’s not a purse. It’s european.” So says Jerry Seinfeld in “The Reverse Peephole” episode. To which George Costanza says, “A man carries a wallet” (George’s emphasis).

I carried a wallet for years, in my hip pocket, like most American men. At some point Tizi commented on my pants, how the fabric was worn thin on my hip pocket. “And doesn’t that blob back there bother you, sitting on it?” she asked me once. I hadn’t thought about it. But now that she mentioned it, Yes it did.

So I emptied my pockets. And I’ve never gone back.

A cursory study of the etymology of “wallet” suggests the accessory used to be a man bag. A reliable unnamed source indicates: “The origin of the word wallet can be traced back from the ancient Greek word Kibisis which was the word used to describe the sack carried by the God Hermes.” That sounds like a stretch to me, but if it’s okay for Hermes, it’s okay for me. An online etymology dictionary I consult suggests wallet comes into English in the 14th century, from Old French “walet,” a term denoting “knapsack,” or from Proto-Germanic “wall,” a word for “roll.” Or possibly from the old French “golette,” for “little snout,” which I do not understand but immediately love. The point being that a wallet used to be a bag. A man bag.

Bags were necessary because the pocket had not yet been invented. Think of it: life with pockets. In Hannah Carlson’s delightful World’s Use of Pockets: Men’s Clothes Full of Them, While Women Have but Few . . . Civilization Demands Them, she notes: “For centuries, how you wore your purse distinguished masculine from feminine dress, but the purse itself did not belong to a single gender.” But in the 15th century, along come pockets, primarily on men’s clothing, signaling, for centuries, the end of the man bag. On men’s clothing, pockets. In which they keep their stuff. When I was a kid, I was frequently made aware of my father’s presence by the coins (he called them “silver”) or car keys jingling in his pocket. He kept a wallet, which he called a billfold (my Italian father-in-law called his a portafoglio) in his hip pocket. In my mother’s case, I recall her reaching into a apron pocket for a tissue, but otherwise, in my memory she is more or less pocketless.

Pants pockets gave, and continue to give, boys and men a place to put their hands. Hands in pockets can give a man a casual, stylish, insouciant look. But there was and is a downside. In 18th century satirical engravings, hands in pockets indicated lechery. When I reached a certain age my father would say, “Don’t stand around with your hands in your pockets, looking idle.”

With the advent of pockets, pick-pocketing became a thing. I was on a crowded bus in Florence a few years ago with a group. A guy I was traveling with advised me and the members of our group to keep our hands in our pockets to protect ourselves from thieves. By the time we got to Fiesole, this poor guy had been fleeced.

I wear my bag slung across my chest, bag left. In an emergency I can reach into it with my left hand and grab my nail clippers. I was pleased to note recently that’s how Indiana Jones wears his bag, bag left. We are men of inaction and action. Now that I think of it, in all the Jones movies, which I love, I have never seen Indie open his man bag and take something out, ammunition for his pistol, let’s say, or a hankie. Well, he knows what it’s for. And I know what mine is for.

A few years ago I guy came to our house to do some work. Tizi chatted him up. She needed a name. I think she was looking for a blacksmith.

“I know one,” the guy said. “I got his name and number right here.”