Rick Bailey's Blog: Stuff happens, then you write about it, page 10

December 18, 2023

My Friend Fennel

Of course growing up in a farm town in Michigan, I never had even a distant encounter with fennel. My parents joked once that Greg Fraser, a kid in town, was sent by his mother to the drug store to ask for anise. And he pronounced it anus. The local druggist, Fred Gaul, must have ratted him out. Making me wonder now: Why the drug store? Would that have been an over the counter remedy? Surely not a controlled substance.

At any rate, with marriage into an Italian family I soon became acquainted with fennel. And with anise, in a flavored liquor, a few drops of which my father-in-law used to flavor his morning coffee. And in a more potent grappa common to the family’s region of Italy, San Marino and Emilia-Romagna, called mistrá. Not unlike ouzo or Sambucca, only more refined, by which I mean not as syrupy as those OTC anise liquors, the one we had in the house was moonshine made by a guy up in the hills somewhere in San Marino. We brought it home in unmarked liter-and-a-half bottles. In addition to functioning as a coffee corrector and a digestivo, Mistrá was also poured over ricotta, with sugar sprinkled over it, to be eaten as a dessert, something my father-in-law was introduced to in Libya before the onset of World War II.

But fennel. When I joined the family we ate it mostly at holiday dinners, as an appetizer with cheeses and salami. Lately I’ve been stewing it. In regional speak they say “in umido” to designate a dish the cooked in olive oil and garlic and tomato and other suitable ingredients. The fennel in umido is just that. The trimmed bulb sliced top to bottom, then further sliced, and slow cooked with a few tablespoons of tomato puree added.

There’s nothing neutral about fennel. Consider the folklore. Prometheus hid fire in a stalk of fennel. Pliny the Elder associated it with purification, helping to cleanse the body of undesirable humors. The ancients believed snakes would rub against fennel to sharpen their sight. The Kitchen Window segment on NPR reports: “In medieval times, fennel was used to protect against witchcraft and evil spirits.” Fennel made bad wine taste good. Paolo Gavin writes in The Tablet, “17th century Venetian innkeepers would offer fennel and nuts free to their customers before serving them inferior wine.” Carry it with you and people would perceive you as trustworthy.

All these reasons and more to eat your fennel.

Cooking time for fennel in umido is 30-40 minutes. You can do it well in advance of the meal, then gently reheat it before serving. It is delicate and other-worldly, and we’re serving it to friends for lunch today.

December 13, 2023

Please State Your Sweet Nothings–from And Now This

Michigan Ear Institute, it’s no surprise, is a noisy place. I’m sitting in the waiting room when Mr. Robinson walks in. He steps up to the check-in window, signs in, and waits. The receptionist looks up. Her lips move.

“What?” he says.

Lips, again.

“What?” he says, again.

“HAS ANY OF YOUR INSURANCE INFORMATION CHANGED, MR. ROBINSON?”

A dinful chat ensues. He eventually takes a seat near me and settles in for the wait. Around us, in the crowded waiting room, there’s the hum of sotto voce talk, some of it not too sotto. I’m here this morning to receive my device, a hi-tech hearing aid that will make life easier, a device that, I am told, will bluetooth to my phone, to the tv, to the world.

As a gag, I decide to document this long awaited moment for my family, who have been putting up with my gradual hearing loss for years. (Last night I thought my wife said something about “deep fleck.” Then, from the bathroom I heard her say: “My upper right bodger is hurting.” When I repeated those exact words back to her, not without relish, she was not amused.) I reach for my phone and try to take a photo of one of my ears, to send to her and the kids. It’s an awkward shoot. You vaguely aim at the side of your head. I consider yelling at Mr. Robinson, WOULD YOU TAKE A PICTURE OF MY EAR? And then think better of it.

Two or three clicks, and I look.

As body parts go, ears, like feet, are intricate but not beautiful.

There are exceptions. Babies’ ears, for example. And feet? A few weeks ago, standing in line at a hotel coffee bar, I complimented a woman on her feet. She was in her twenties. She had long, thin feet. Not swim-flipper-long; for her they were right-sized. She was wearing flipflops, so I could see they were slender and also nicely tanned.

“Can I tell you something?” I said.

She turned and looked a look at me that said, What?

“You have beautiful feet.”

She glanced down, then back at me, and said, “Thanks?”

After she left, I asked an older, hearing-aid-aged woman waiting for her coffee, if what I said was inappropriate. She said she thought it was quite lovely.

As body parts go, ears, like feet, are intricate but not beautiful.

This is not a foot fetish. It’s more like a habit of mind–where I focus my attention, on shoes, on feet, on small details. A few years back, when I circled the 14th century hall at the top of the stairs in the Bargello Museum, I took pictures of feet, assembled a little gallery of my own on my iPhone, Studies in Feet. Pictured above, Adam and Eve’s feet, attached to the rest of our foreparents in a sculpture by Baccio Bandinelli. Below, the foot of a saint. I would not call this foot beautiful, but it has a kind of grandeur. It is a formidable foot. Like most people I am a photo idiot in museums, taking pictures of what I’m looking at, pictures that will tell me and others, later, I was here. “Hey, you saw the David?” (Awesome feet.) But perhaps unlike other people, I rarely photograph the whole painting or sculpture. I stand close and shoot tiny details, the two-inch tall kid in the corner of the painting, not the main character; the old woman touching her upper lip with a long thin index finger, a sorrowful man at the edge of the crucifiction.

At the hotel coffee bar that morning, I did not photograph the woman’s foot. That would have been weird.

The photos I take of my left ear in the Michigan Ear Institute this day are a little too close, not well lit. And, you know, hairs. And, you know, ear stuff and sluff. In a word, the images are kind of gross. I decide not to share.

I swear I can hear the hinges of my jaw, the smack of my lips opening and closing,

A few minutes later, back in one of the office exam rooms, Elaine the audiologist shows me the device, two units the size and color of cashews, with thin wires attached to mini loudspeakers, one for each ear. I hand her my phone and she performs the setup, then explains how to toggle to various settings: all-around, restaurant, outdoor, ultra focus. I can also create custom settings I might need: for the grocery store, for the library, for the front seat of the car.

“Your phone will now ring to your hearing aid. Do you want that?”

I tell her I don’t know.

“Audio on your phone, like who’s talking to you, will automatically go to your hearing aid. Do you want that?”

I tell her I don’t know.

“Do you listen to music on your phone? We can stream directly to your hearing aids.”

“I’ve heard of that.”

“Some people like it.”

“Goodbye, ear buds.”

“Yup.” She pushes a button on one of the cashews, slips a hearing aid over each ear.

“Wow,” I say.

“Yeah,” she says, very audibly. It’s like someone turned up the treble. I tell her this. She says I’m going to hear things I haven’t heard in a while.

“Wow,” I say again, “you sound different.”

I make an appointment to return in a month.

In the car, the turn signal’s BLINK-a BLINK-a BLINK-a is deafening. I turn on the radio and turn it back off. I swear I can hear the hinges of my jaw, the smack of my lips opening and closing, the clack of my teeth. Who knew a head makes so much noise? When our son was little I used to hold my ear next to his cheek when he ate cereal, listening to him crunch and chew. My crunch and chew, I imagine, is going to be deafening.

At home the garage door closing sounds like a 747 landing. The sound of my urine spashing in the toilet bowl is startling, the flush as well. The wood floors and stairs crackle beneath my feet.

“How is it?” my wife says.

I open the app on my phone. “I have to learn this thing,” I say, meaning the app.

“But can you hear better?“

“I hear louder. Everything is sharp,” I say. “Everything crackles.”

Evidently my hearing deficit is in the mid- to high-frequency range. In the office Elaine showed me my speech banana (a term I warm up to immediately), which is a picture of frequencies and decibel ranges in and out of reach. I can’t hear whispers, I now understand, because a whisper is a high frequency sound. In bed at night, when my wife whispers something (and we still whisper in bed, even though it’s just the two of us), I have to turn, draw close to her, and present an ear. Did you lock the back door? WHAT? Did you lock the back door? WHAT? I can no longer hear her sweet nothings. Please state your sweet nothings, I want to say. But of course they would lose something.

The device corrects for these deficits, enhancing high frequencies–with a vengeance. Not in bed.

Just now she’s watching a rerun of Rachel Maddow. Rachel’s voice hurts. “Can we turn that down?” I say.

I now understand, because a whisper is a high frequency sound. In bed at night, when my wife whispers something (and we still whisper in bed, even though it’s just the two of us), I have to turn, draw close to her, and present an ear.

I could have used these things a few weeks ago. I was in a hotel coffee bar that morning looking at feet because I woke up in a hotel in Grand Junction, Colorado. We were on the return leg of a cross country road trip.

Car travel poses all kinds of problems for the hearing challenged, even the slightly challenged, which is how I would describe my case. In a 5000 mile drive, we rode over every imaginable road surface, the tire-to-surface sound ranging from hum to hiss to whine to growl to roar. Toss in a little tinnitus, sometimes quite a lot of tinnitus, and an acoustically imperfect Chrysler van (think echo chamber), and you have your work cut out for you. Each day, my wife would look out her window and remark on the scenery, often speaking in the direction of the window. I listened to the back of her head, wondering: Is she talking to me or herself? We clocked 6-8 hours a day in the car. Daily I clocked 50-100 requests that she re-remark. I drove leaning in her direction. What did you say? I didn’t hear that. Say again? Huh?

That got old, fast.

I am a firm believer in technological enhancements, especially in the area of travel. On a long flight I wear noise canceling headphones, attach them to the in-flight entertainment system or to my phone, and enjoy enhanced sound. Our whole road trip to California and back was on my phone, itinerary, route, hotel reservations, photos. The navigator on the dashboard was my friend. It predicted ten hours driving time from Mariposa to St. George, it told me when to turn left, it rerouted us around heavy traffic in Barstow.

But enhancements come at a cost.

One night in St. George, Utah, out of nowhere this guy says to me, “Hey, man, I like your shoes.”

So: someone is looking at my feet. A like-minded person?

My wife and I are standing in the entrance of a restaurant called the Painted Pony, waiting for a table. We’ve just driven 600 or so miles, a lot of it through the Mojave desert. It’s pushing 9:00 p.m. We’re hungry, tired, and crabby.

I don’t often hear compliments on my shoes, for good reason. I tend to wear shitty shoes. So this is a surprise, a lift. The guy is tall and thin, with a head of sandy-gray hair that reminds me of the desert we just passed through.

He points at his shoes, which are almost identical to mine. More sandals than shoes, with hard soles, they’re good for hiking if you don’t mind getting your feet dirty. I tell him we just drove in from Yosemite. When he asks what route, I shrug and say I turned left when the navigator said to. He nods me a slightly judgmental nod, which I feel I slightly deserve. Nope, I can’t name a single road we drove. After Fresno, I can’t even remember the name of a town we drove by, other than Las Vegas. When we get home I plan to read Pathfinder, a book I bought in Mariposa. It’s a biography of John Charles Fremont, a guy, the title suggests, who chose his own path. Well, not me.

Next time, this guy says, try 95.

I’m always grateful I don’t have to buy the whole LP, when I want just one song. In this way “Bongo Bongo” is kind of like Adam and Eve’s feet, choosing the part over the whole.

That night before bed, I voice-to-text myself a note to that effect. Try 95. Then another note. Find 95 on a map. Then another note. Find a map, buy a road atlas. Here’s the problem: On my phone, on the dashboard navigator, you can zoom out, but the view is terrible, so minimal as to be altogether useless. This is not an enhancement. Sometimes you want to see the whole state. You need the global view to know where you’ve been, where you are, and where you’re going.

My wife asks one night, “What’s that noise?”

We’re home from our trip, relaxing. I have enhanced hearing. She’s sitting on the couch reading a book entitled Q, historical fiction set during the time of the Protestant Reformation, a period full of war, intrigue, and skulduggery. I’m listening to music.

I tell her I’m bluetoothing music to my hearing aid, which is what she hears. To her it sounds like sssssssssssss. To me it sounds a little like that too.

“Bongo Bongo,” I say.

“What?”

“‘Bongo Bongo,’ by Carlo Valentino.”

“Am I supposed to know that song?”

“He’s Italian.”

[Thank you for sharing this post with a friend who reads.]

A song I found when I was searching for alternate versions of “Via Con Me” (“Come Away with Me”), an alternative to Paolo Conte’s recording. “Bongo Bongo” is a wacky swinging number with horns and a slick steel guitar. I bought it for $1.29. I’m always grateful I don’t have to buy the whole LP, when I want just one song. In this way “Bongo Bongo” is kind of like Adam and Eve’s feet, choosing the part over the whole.

“Bongo Bongo” would be a perfect soundtrack for a cruise west on Route 66, which I can find on my phone, on my computer, on the car navigator, and now on the National Geographic road atlas, which Amazon Prime has just delivered. It’s a retrograde accessory. And I am thrilled.

But that sssssssssssss. On my hearing aid, correcting for my mid- to high-frequency deficit, the bluetooth music sounds like someone turned the treble up and dialed down everything else. It has a scratchy, staticky quality. What you get from a loudspeaker the size of the head of a pin.

“This thing needs a woofer,” I say.

“A what? Why? What are you talking about?”

My hearing aid and its hi-tech software correct for my speech banana, which is not the same as my music banana. “Bongo Bongo” does not sound good. I toggle to the Beach Boys’ “I Get Around.” Bad sound. I try a cut from the Paul Desmond LP, “Bossa Antigua,” which I downloaded (in its entirety) after hearing it that night in the Painted Pony. Desmond’s alto sax should sound like velvet. It does not.

Something gained, something lost.

While my wife reads her Q, I fiddle with app settings, adjust the EQ on my iPhone, trying to improve the sound. I raise the bass, dial down the middle, zero the treble, in order to achieve near earbud quality. It works, sort of. I save the settings, call it “Music.” I’ll be able to select that setting next time I’m at the Ear Institute and want to listen to the Wayward Sisters’ “The Broken Consort” in the waiting room. Just as I’ll be able to select “car,” the custom setting for when we get around and I’m listening to the back of my wife’s head.

Alas, no setting for sweet nothings. At least not yet.

December 6, 2023

Kissing Age–from American English, Italian Chocolate

Last night, halfway through Jeopardy, I asked my wife if she wanted to suck face. She shook her head in disgust. It’s not our usual nomenclature.

“How about a smooch?”

“No.”

“A peck?”

“No.”

“A buss?”

“Why do you talk that way?” She pointed at the TV. Alex Trebec was introducing Arthur Chu for the tenth time. Was there anything left to say about Arthur?

While the Double Jeopardy categories loaded, I watched her. She saw me, and refused to make eye contact. The truth is, I didn’t want to kiss. I just wanted to use the expression, “suck face.” And I wanted to see what her reaction would be. Finally, she glanced in my direction, gave her head another dismissive shake, and told me I was a fool.

Wiktionary teaches us, as if that’s really necessary, that “suck face” means “to kiss, especially deeply and for a prolonged time.” From Free Dictionary (by Farlex): “to engage in French kissing (soul kissing).” And the online urban dictionary, which I use when confronted with youthful patois and argot, defines “suck face” as “a game where you make out in the least atractive [sic] way possible.”

I didn’t know it was a game. Who would want to watch?

The first movie kiss was filmed by Thomas Edison in 1896. I’ve seen the film, and the smacker. It’s a recreation of a stage kiss from a play called “The Widow Jones.” Edison must have been prim as a director, instructing the actors not to suck face. The film runs 47 seconds. It’s easy to miss the kiss. Imagine a movie today called “The Widow Jones.” Not much shocks us. For some time now, I’ve been inclined to avert my gaze when people kiss in the movies or on TV. The kissing is usually so earnest and hungry, so noisy. Do they have to slurp like that? I can’t watch. I do not find it atractive.

My first episode of real kissing was deep and prolonged. I was in eighth grade. It took place in a two-car garage that was converted into a rec room. We were eight or nine couples. We played records and milled about for thirty minutes or so, until the lights were dimmed and we got down to serious kissing. From couches in corners, from large lazyboy recliners and a few treacherous beanbag chairs came the sighs and sounds of slippery wet mashing. Again and again that evening, I had the sensation of looking at myself from above, both participant and spectator. So this is what it’s like, I thought.

For some time now, I’ve been inclined to avert my gaze when people kiss in the movies or on TV. The kissing is usually so earnest and hungry, so noisy. Do they have to slurp like that?

At intermission, a female friend I was not kissing asked me how it was going. What I wanted to say was, It’s actually kind of boring.

“Does she like it?”

I told her I wasn’t sure.

“Did you feel her up?”

“What?” I felt my face go hot and red. Didn’t she know I was a Methodist?

Sometime after that rec room romp, Lila Elembaas came down with mono, which my mother informed me was “the kissing disease.” Lila was older and, I could only assume, way more advanced. Still, it was unsettling news. A few years later, when I learned to play blues harmonica, my mentor, Rod Gorski, told me not to French my harp. “You know how you kiss your mother?” he said, “the way you purse your lips?” He demonstrated: a round, tight pucker, at its center a whistle-sized aperture. “Like that,” he said, “Mainly, you draw. That’s where the good sound is.” From that sucking kiss, soulful music.

Only now, in 2014, is there a word for French kiss in Le Petit Robert dictionary (galocher), adding to, and perhaps improving upon, baiser avec la langue (kiss with the tongue)

Experts tell us that in human history, kissing is a recent development. Texans, for some reason, are all over this subject. Vaughn Bryant, an anthropologist at Texas A & M University, authority on the evolution of human kissing, thinks kissing probably happened by accident. Like other creatures, humans must have checked each other out by sniffing. Then one day Moog’s lips brushed against Gorga’s. She said, Hey, what was that? And he said, I don’t know, but I liked it. They got right to work. The rest is history.

In 1500 BC, in texts of Vedic Sanskrit, you will find references to licking and “drinking moisture of the lips.” In Song of Solomon, “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth. For thy love is better than wine.” Yea, verily. The Bible says it’s so. Sheril Kirchenbaum, research associate at the Center for International Energy and Environmental Policy at the University of Texas at Austin, reports that in the early 20th century, perhaps 90 percent of cultures worldwide kissed. “With the rise of the Internet,” she hypothesizes, “and ease of travel in the 21st century, it’s fair to assume that nearly all of us are doing it.”

None do it better than the French, we might think, though it appears there was plenty of Frenching going on long before there was a France. And if it’s their thing, why is their language so impoverished in that department? Only now, in 2014, is there a word for French kiss in Le Petit Robert dictionary (galocher), adding to, and perhaps improving upon, baiser avec la langue (kiss with the tongue). The British, a poetic people, call it “snogging.” I’ll take suck face over that, but that’s me being patriotic.

My wife’s culture is kissy. In Italy you may be called upon to greet loved ones and friends with two kisses. Remember, right cheek first. I tend go left (I also twirl spaghetti counter clockwise), crossing the intersection diagonally, which leads to awkward moments and embarrassing collisions.

This kissing dates back to Roman times. Precise in all administrative matters, the Romans distinguished between the osculum, a kiss on the cheek; the basium, a kiss on the lips, and the savolium, the deep, prolonged, soulful pre-French kiss.

She is a far better linguist than I am. She learned Latin from the nuns. But I can’t imagine asking my wife, Are you up for savolium? It rhymes with linoleum.

She’ll give me a signal. Something obvious, like Kiss me, you fool.

November 29, 2023

No Exit from Guyville

“So sorry to hear of your loss,” I wrote. “We’ll be thinking of you guys.”

It was an email to friends ten years our senior, a couple who had recently lost a father 94 years old. Not to Coronavirus but to plain old old age. It was an ordinary passing–although no passing is ever really ordinary. I re-read the sentence, stuck on “you guys,” thought about it, then rewrote. “I understand you’ve had a death in the family. So very sorry.”

You guys? Really?

I know these people well enough to be sure they would not object to being “you guys.” Who would object? Grateful for the expression of sympathy, they probably wouldn’t even notice. But somehow, the term didn’t feel right. Any more than it would have felt right to tell them, “See you at the funeral, you guys.”

Last summer at a wedding my wife and I attended, during toast time at the reception, the brother of the bride, an impressive fellow impeccably decked out in a black tux, delivered a long and engaging speech. He’d obviously thought about what he was going to say, but maybe hadn’t rehearsed it much. He would begin to finish his remarks, then remember something he’d left out. “Wait,” he’d say. “There’s another thing I need to tell you guys.” He’d riff on the new subject, run out of things to say about that, start a little peroration, then, “But just one more thing, you guys.” He really stretched it out, until most of us guys I think had started to get a little restless.

Man and woman, boy and girl alike, we’re all guys these days.

Guys, it is true, comes in handy. It is a warm, readily available plural, like folks.

Hey, folks, nice to see you again.

What can I help you with, folks?

That’s all, folks!

Except guys is not like folks. Take the s off folks and you get an archaic-sounding noun used mainly by older folk. More commonly, minus the s you get an adjective. Folk lore. Folk music. Folk tales.

Take the s of guys and, it ain’t complicated, you get a dude. What’s that guy looking at?

Not only do you get a dude, you also get a proper name for a dude.

When I was a kid there was a guy in my home town named Guy Welch. I’d say he’s the only Guy I’ve ever known. In the years after that, Guy never rose very high on the list of popular names for baby boys. Today, I have no Guys in my address book. But if you look into it, there are a few guys named Guy in popular culture and in history: Guy Pierce, Guy Ritchie, Guy Fieri, a tennis player named Guy Forget, Guy Lombardo. Pope Clement IV (b 1190) was a Guy. Guy Fawkes (b 1570) was a very important Guy. The first Baron of Dorchester (b 1724), he was a guy named Guy. Then there’s the name that rhymes with key, I mean Guy (Ghee). Guy de Maupassant, for example, and the majority of Canadian hockey players.

The key Guy (not Ghee), the one we can thank for all of us being guys today, is Guy Fawkes, a Catholic terrorist who planned to blow up Parliament in 1605. The plot failed. Since then, for hundreds of years, on the night of November 5, that Guy was been burnt in effigy, and those effigies were commonly referred to as Guys. By the 19th century guy began to signify “any scary-looking or badly-dressed person,” according to the Boston Globe, until, in 20th century American, guys became a term that designates everyone.

Today guys are also gals. The term is gender-neutral. The reverse, in our guy-centric language, is not true. If you say, “There’s another thing I need to tell you gals,” you’re talking to women.

Does this guy-gal thing matter? It depends on the person you’re talking to.

While guy comes from a famous Guy, and probably, etymologically speaking, from the Italian Guido (Guy Fawkes is also referred to as Guido Johnson), gal’s origins are pretty mundane. According to my grammar detective, “Gal first appeared as slang in England in the late 18th century and originated as a Cockney pronunciation of the word ‘girl.” Gel, then gal.

In an Atlantic Monthly article titled “I’m a Gal, Here Me Roar,” Lily Rothman observes, “If all who identify as female were to go from girl to woman when they turned 18—or 21 or 13 or 16, the scales of language would still be unbalanced. A boy doesn’t just instantly become a man: he gets to be a guy.” Rothman is very pro-gal. She writes, “Gal has all the best qualities of guy. It’s casual. It’s all-inclusive. It’s friendly and fun. It’s short and sweet.”

I have an acquaintance who operates a small business. In conversation he will occasionally refer to a couple gals they have working in the office. I kind of duck my head when I hear that. Is gal okay?

On a helpful website called GirlsCantWhat? hundreds of people weighed in on the issue. Herewith some responses to the question, Is gal okay?

Lorna Jane: Here in the UK we don’t use “gal” as a common form of address but I don’t think it’s offensive.

Anita: Gal is very offensive to me.

Sue Mam: Gal is offensive to me too.

Barbara Wilson: The word Gal was a derogatory word used in the South to demean women of color…I speak from experience.

Lissa: I think Gal is fine, I personally don’t like to be called a mam, because I think it sounds old.

Bunny Words: Gal is very offensive to me.

Marie: Everyone I know who identifies as a gal is gay.

Ann Hill: Gal is very offensive. No matter how many times I’ve told my husband this he still says weather gal or refers to women physicians as gals.

Gretchen: As I see it, it’s not offensive. I think it is the equivalent to “guy”.

Beth: “Gal” just needs to be dropped. I am a white woman and anyone who refers to me as a gal will get called on it.

Paula the Surf Mom: This PC stuff just goes too far sometimes… There is nothing wrong with “Gal”

Jeff Walker: What offends you about the word gal? I think the word woman is much more offensive when used in a sentence.

Mary: Jeff, you are not a woman.

Some years back, in a class I was teaching, a woman sitting in the back of the room corrected me when I referred to her as African-American. She said she was Black. And I thought: of course you are. To every extent possible, you get to decide what to call yourself. And the rest of us can just get over it.

I’ve been trying to remember how I used to greet a class when I was still teaching. Good morning, class. Hello, students. Hey, all. S’up, everybody. And, yes, probably on occasions, Hey, guys. A prof whose class I took when I was undergrad always said, Good morning, scholars. In grad school, the most engaging lecturer I ever listened to always sauntered breezily into class and said, Hello, good people.

Salutations, obviously, are situation sensitive. Friends, Romans, you guys: lend me your ears…. Four score and seven years ago some folks brought forth on this continent…

In June of 1993, Liz Phair produced an album called “Exile in Guyville,” a song-by-song response to the Rolling Stones’ “Exile on Main St.” She says of the LP, “[There was] this kind of guy mentality, you know, where men are men and women are learning. [Guyville guys] always dominated the stereo like it was their music. They’d talk about it, and I would just sit on the sidelines.”

Perhaps there is no exit from guyville, in music and in daily life, unless we really mind our mouths, one guy and one gal at a time, choosing our words carefully. Hey, guys, good to see you. How you guys doing? What’re you guys up to? Mind if I join you guys?

One guy less here and there, who would possibly notice?

November 22, 2023

Grubs for Lunch–from And Now This

My friend Luigi asks, “Do you think prehistoric people were happier than we are?”

We’re standing in line at an airport food vendor called the Dogpatch Bakehouse. Our flight is on time, but my stress level is high. I took a few wrong turns driving from the hotel to the airport, then left my phone in the rental car and had to run back to retrieve it, down two long flights of stairs, down two floors in a hesitant elevator, and back to the rental car parking garage, where the phone’s recovery was very gradually accomplished.

I wanted stalactites, but Erk here is a stalactite nut.

I wanted stalactites, but Erk here is a stalactite nut.Dogpatch advertises bold coffee and local ingredients, vibrant salads and delicious sandwiches. The line is long. When we finally get to the counter I count six vibrant salads.

We’re on our way home from a raft trip on the Colorado River. Before bedding down the first night, our guide told us about the hazards: crows (they’ll steal your stuff), red ants (be sure to brush them off, if you slap them and they will bite), scorpions (the very painful but not deadly variety), rattlesnakes (more than a theoretical possibility), and mountain lions (mountain lions!). Have a good sleep.

Here at Dogpatch, I point the server at the quinoa and kale salad and the roasted squash, asking for a scoop of each. When it’s his turn Luigi nods yes, he would like his delicious sandwich warmed up on the panini grill. In an hour we’ll be in the air. Four hours and 2000 miles later, we’ll be home.

We tend to think of our hunter-gatherer foreparents as living Hobbesian lives–nasty, brutish, and short. Their lives must have been just that, possibly even less, but how do you measure happiness? A study by F.D. McCarthy and M. McArthur published back in 1960 suggested hunter-gatherers probably enjoyed quite a lot of leisure time. In 1968, Canadian anthropologist Richard Borshay Lee, in a study of the !Kung Bushmen of Dobe, argued that those guys worked as little as 12-19 hours a week to keep the pantry stocked. Think of all that time on their hands, to dedicate themselves to their cave painting, to hunter-gatherer song and poetry and sport, and, tool-users that they were, to work on hunter-gatherer gizmos to make life a little easier.

When I get home, there are a few while-you-were-gone annoyances. A hundred or so emails, the most recent one with “Got grubs?” in the subject line. A love letter from a healthcare provider: “Contact us about your bill.” Then, when I open a door down in the corner of the basement, the one to my little wine closet, I see a puddle of water on the floor.

We have this foolish idea our homes are impermeable barriers between us and nature. Dark outside, light inside. Cold outside, warm inside. Hot and humid outside, cool and dry inside. Bugs, dirt, water–outside. When that barrier is compromised, it’s a shock, cause for alarm; in the case of water, it’s a crisis.

Evidently it’s been raining for a few days, torrential rains that make you think of the end of the world. I fetch a sponge and bucket, sop up the water. I know what I’m in for. A couple hours later the water is back, more of it. I fetch sponge and bucket, sop up the water, this time on my hands and knees.

I anticipate a couple days of sopping and mopping, so I decide to employ a labor-saving techology, a shop vac I keep in the garage for vacuuming car interiors. It’s also a water management system on wheels. I carry it downstairs, roll it to the corner of the basement, and, standing upright, vacuum the water. It works great, way better than sponge and bucket. For the next 48 hours, as the rain lets up and the seepage gradually subsides, I remove unwanted water from my wine closet. It’s a wonderful appliance. I love using the shop vac so much, I almost wouldn’t mind if it rained a little more and the water hung around a few more days.

Next day I’m on the phone with the out-of-state healthcare organization I visited a month ago. For two hours in emergency I’ve been charged $2600, a considerable portion of which, pretty good insurance notwithstanding, is in contention. I wait through the initial phone menu–if you know your party’s extension, for outpatient, for in-patient, for social worker, for lab results, for billing, for room service, for the morgue–and finally get to a person in billing.

“Will you hold, please?”

“If I must.”

It’s a long wait. I’m a motivated caller. While I wait I listen to You’re-on-Hold Radio. Right now they’re playing synthesized elevator music, a sluggish, mucky rendition of “New York, New York.” Given the current state of technology, it occurs to me they could make your wait time a lot less painful. They could patch you through to a Pandora option, providing you with some choices in music–for Frank Sinatra, press 7, for the Beatles, press 8, for Beyonce press 9, for Best of Mozart, press 10. Every 30 seconds, the music stops and I’m asked if I’d rather just put the bill on my credit card and hang up. Would I ever. But…

Finally, a person.

“This is Elsie. How can I help you?”

We talk. Her voice is calm and reassuring. I explain the purpose of my call. When she asks, I read her my insurance info: enrollee code, plan number, group number.

“Can you please confirm your D.O.B. and sosh?”

She says she has to ask. I give her my dob and sosh, thinking as I do, Do you have to say “sosh”? She thanks me and says she’ll be right back.

And I’m right back, on You’re-on-Hold Radio, listening to the elevator version of the Carpenters’ “We’ve Only Just Begun.”

I know there are compassionate options to You’re-on-Hold Radio. I’ve heard them. I’ve been on hold before and actually wanted to stay there. One time I was, like, Hey, it’s The Talking Heads. Another time, Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings.” Once or twice, when I’ve been clicked back to business at hand, I wanted to say, Can you put me back on hold for a few more minutes?

Now on the line again, Elsie says she got it. It was a Z instead of an X in my insurance ID. Human error. They had my name right, my address right, my phone number, dob and sosh right, but the computer can’t process the claim if there’s a Z instead of an X. She says she’ll submit my claim again. Can she help me with anything else?

Oil spill, building collapse, plane crash, car accident, food poisoning, computer virus–human error these day is amplified, made exponentially worse given all the people and all the tech involved. And then there’s simple ordinary life as we know it, and cumulative, pedestrian error. New York, it seems, is about to ban the use of plastic straws. Imagine, a gazillion plastic straws. Can plastic water bottles be far behind? In England, a whale that washed up on shore had 50 pounds of plastic in its belly. This summer Lake Erie will have an algae bloom that may choke off the water supply to Toledo. In some respects maybe our foreparents didn’t have it so bad.

Nasty, brutish, and short? Maybe not so short. Satoshi Kanazawa, an American-born British evolutionary psychologist at the London School of Economics, offers a statistical analysis that suggests prehistoric folk probably lived long lives. Life expectancy numbers, Kanazawa argues, are skewed by child mortality rates. If a human being made it to age 6, or better yet, age 12, chances were he or she would live to be 70 or even 80 years old.

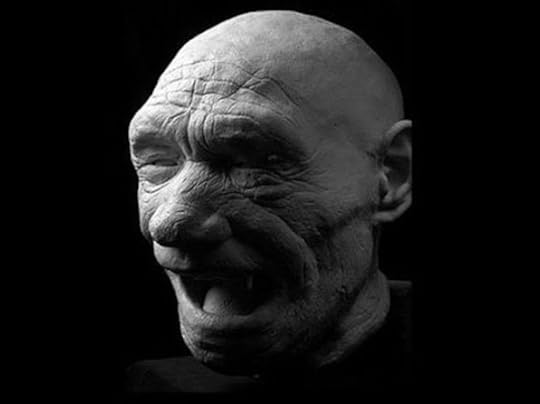

Brutish? Probably. But consider The Old Man of La Chapelle, a Neanderthal from France who lived some 50,000 years ago. His dental records–that is, what scientists can glean from looking at his jaw and his teeth (lots missing teeth, not a surprise, but with ample bone reformed along his gumlines)—well, his bite indicates that he must have lived to a ripe old age and maybe even had a special old-guy-with-no-teeth diet; that is, someone was taking care of him. Furthermore, skeletal examination points to evidence of old-guy complaints, such as arthritis.

So maybe life in pre-historic times wasn’t so bad, was only somewhat nasty, brutish, and short.

Then again, red ants.

And then again again, mountain lions.

Our foreparents wouldn’t have worried so much about a little water leaking into their domicile. They had more pressing concerns.

Before going to bed, I am grateful not to be sleeping on a pile of rocks. I use my electric toothbrush and Shaper Image Nose Hair Trimmer, and expect to awaken dry, bite-free, with all my limbs intact. Given the time, when the basement is dry, I may even go outside and try to find out if I do indeed have grubs in the yard.

Given the choice between grubs for lunch and grubs in the grass, I would choose the latter. We live when we live. It’s not all good. Maybe that’s the universal human condition.

November 15, 2023

Wreckage–from The Enjoy Agenda

I was ten years old the first time I saw a real car accident and its aftermath. It was a humid summer evening. My father and I were closing our service station when the township siren sounded. A cop car screamed through town. Then the phone rang. My father took the call, listened a few seconds, nodded and hung up. He pointed me toward the door and said, We have to go.

Half a mile out of town a fire truck was already on the scene, along with the cop car, their headlights trained on a station wagon flipped on its top in the middle of an intersection. Another car was nose-down in a ditch, its engine still running, tail lights on, a turn signal flashing. I stayed in the car while my father got out and talked to the constable. Sitting on the pavement next to the overturned car was a large man, naked to the waist and barefoot. His legs were crossed in front of him. He was bleeding from the head; more blood shined on his chest and stomach. Every so often he lowered a hand to the ground to steady himself. I learned later that the driver of the other car was a local man the constable and firemen knew, that they joked with him as they pulled him from his car.

I swept up broken glass, listening to the crackle and tinny voices coming the cop car radio, avoiding the spot on the road where the bleeding man had been made to lie down.

We rushed back to town for our wrecker and then returned to the accident, where we righted the overturned car and winched the other car out of the ditch. At some point, my father handed me a shop broom. I swept up broken glass, listening to the crackle and tinny voices coming the cop car radio, avoiding the spot on the road whI swept up broken glass, listening to the crackle and tinny voices coming the cop car radio, avoiding the spot on the road where the bleeding man had been made to lie down. Eventually in the distance, there was another siren, as an ambulance bore down on us and came to take the injured men away.

We towed both cars into town, leaving them at one of the car dealers. In the cab of he wrecker, my father patted my leg and asked if I was all right.

“You saw something tonight,” he said.

“I’m okay.”

“Are you sure?” He patted my leg again and said he thought if I had trouble sleeping that night, I might stay home from school and sleep late the next day.

I think of this experience, even to this day, whenever I see car parts at the side the road, on the shoulder, in the median, at the edge of a ditch. It’s a common sight these days. You see the shiny decorative crosshatching of a grill, fender liners, smooth black plastic splash guards, whole bumpers, sometimes an entire front end module. It’s a new kind of litter, all this lightweight wreckage left behind (I don’t recall ever seeing a heavy, shiny chrome bumper along the road when I was a kid). Even more striking is the sight of a smashed car on a truck bed that passes you on the road. Suddenly the perfunctory mortal danger of your commute to work or your trip to the grocery store or to Home Depot becomes apparent. There’s death out there. In Lives of the Cell, Lewis Thomas speaks of “death in the open,” how unnatural it is to see an animal’s remains along the road. “It is always a queer shock,” he writes, “part a sudden upwelling of grief, part unaccountable amazement…The outrage is more than just the location; it is the impropriety of such visible death, anywhere.”

Must we be reminded?

On the other hand, what if we want to be reminded?

Three days a week we would see her reading while walking the treadmill, working muscle groups on the machines with her eyes closed in concentration.

This woman named Lenore worked out at the facility where my wife and I go. She was tall and thin, well into her seventies, I would say. She kept her brown hair cut in a bob and had about her a natural elegance and athleticism. Three days a week we would see her reading while walking the treadmill, working muscle groups on the machines with her eyes closed in concentration.

I asked her one day, “Were you a dancer?”

She blushed. “Why do you ask?”

“It’s your hands,” I said, “the way you hold them when you bend.”

She said yes, she had studied dance, a long time ago.

I was afraid I had embarrassed her and tried not to watch her on our days after that, but there was something so poised and collected and unself-conscious about her movement, I wanted to look.

Then she missed a few days. She told my wife she wasn’t sleeping well. Then she missed a few more days. And then she stopped coming altogether. She died in just a few months, without having visitors, without returning telephone calls.

Thomas takes the long view, noting that all the billions of us on earth today are on “the same schedule…All of that immense mass of flesh and bone and consciousness will disappear by absorption into the earth, without recognition by the transient survivors.” I know this, and accept it. What are the options? Nevertheless, every so often I find myself standing by the side of the road, a transient survivor, shocked and diminished, grasping for hands that are not there.

November 8, 2023

The Scream in My Heart–from And Now This

Chimps are funny.

When I was a kid there was a television commercial for Red Rose Tea. Four chimps, dressed in plaid jackets and black slacks, playing swing music at a club called The Savory Ritz. On stage there was piano chimp, trombone chimp, and string bass and drummer chimp. Also, in the foreground, lady and gentleman chimp swing dancing. How could they resist? Man, that chimp band could swing. In the last seconds of the commercial, piano chimp channels Louis Prima, leaning into a bistro microphone and chanting, Red Rose Tea! Red Rose Tea!

It was a great commercial. What made it great was the stressed syllables. Red rose tea (rest). Red rose tea (rest). Red rose tea (rest). Those stressed syllables were hammers. The message was pounded into your brain. What great pounding.

It is not an exaggeration to say that over the years, those four chimps and their Red Rose Tea have posed an occasional threat to my marriage. Anything vaguely trochaic like that (a stressed syllable, followed by an unstressed one), I’m likely to get the chant. The latest occasion was just the other day. My wife and I were out for our morning walk.

On these walks we look forward to meeting dogs that have become our friends. One dog in particular, named Echo (Ech-oh), has stolen my wife’s heart. He’s an ancient collie that lives on Pine Tree Trail.

“I hope we see Echo this morning,” she says, innocently enough.

“Yeah, Pine Tree Trail,” I say, relishing those sounds. And like magic, the two stressed syllables call forth my fond memory of the chimps, and I start chimp-like chanting as we walk, “Pine tree trail. Pine tree trail. Pine tree trail.”

And she says, “Don’t do that.”

“Pine tree trail.”

“Please, don’t do that.”

“It’s trochaic,” I say.

“I don’t care. You know I hate that.”

I know she hates that. But I can’t help myself. Or I choose not to. We carry on with our November walk. I shudder against the cold.

“Why don’t you wear a hat?”

“You know,” I say.

“You lose most of the heat in your body through the top of your head.” It’s 8:00 a.m., 39 degrees, it’s Michigan gray, damp, bone-chilling cold.

“I know that.”

“So?”

I take off my scarf and reapply it, giving it a double wrap around my neck. I tell her my head will get used to the cold. My head will be okay. “Unlike you,” I say, “I do not look great in hats. You know that.”

Hats and I do not really get along. Fortunately, an instance of my great good luck: that morning back in January of 1974, the hat I was wearing did not come between us, did not point to a flaw in my judgment she could not overlook. This hat was a knitted thing the color of pie crust, with a short bill on the front. It lay across the top of my head like an overturned pie, or a large deflated balloon. It had a pom pom the size of a tennis ball on top. I could feel it bounce when I walked. Still in college at the time, I wore this hat when I walked across campus. I imagined it made a one-word fashion statement, panache.

Years later, after we were married, looking back at that hat with disgust, my wife suggested a different word, dork.

I wore it the morning I walked into the Quirk building to sign up for Shakespeare’s Richard III auditions. There was an actual British director, a visiting professor from Reading, who was going to direct the play. He was tall and thin. He favored heavy turtleneck sweaters and tight pants. He exuded panache. The costume designer’s office was in the front of the building. That’s where you signed up. And that’s where my wife, who was working in the costume design program, saw me for the first time. Our coming together would be months in the future. She told me later she was repelled by my hat.

We walk together now, in the cold.

Our marriage has lasted 44 years. In any marriage you can picture a balance sheet, in one column “how do I love thee,” in the other “how do you piss me off.” Keeping things in balance, or better yet, slightly tilted in the direction of “how do I love thee,” requires self-control and casting off old habits. Old encrusted, deeply rooted habits you may take simple pleasure in. I have a few of those. For her, I know, I am a struggle.

The problem with music is that it nests in the synapses of your brain. Red Rose Tea! My brain is like a jukebox. I have only partial control over what’s playing. Once it’s in there, to paraphrase Chaucer or Shakespeare, music, like murder, will out. I heard her say to a friend the other day, “When we’re out walking, he sings all the time. He whistles, he hums. He never shuts up.”

It’s true. For my birthday a few weeks ago, my daughter bought me the Paul McCartney book set of all those Beatles lyrics, all those songs. So I’ve been singing a few of those while we walk. Today it’s that old song of theirs, “I Wanna Be Your Man.” I didn’t need the book to remind me of the lyrics.

I’m singing, “I wanna be your lover, baby. I wanna be your man.”

She does not hum along. She does not snap her fingers. She does not look at me. That would be encouragement.

“Tell me that you love me, baby. And that you understand.”

Nothing.

“There’s a great scream in this song,” I say.

“Oh.”

“I never learned to scream.”

These past weeks we’ve both been through minor cases of Covid. Both of us were twice vaccinated, so you could call it Covid-lite. But heavy enough we haven’t walked our long walk in a while. And just before our Covid we were out of town for a month. This morning, feeling like survivors, we’re looking forward to resuming our long walks, where we will see our dogs.

Our dogs.

Neither of us, in point of fact, is a dog person. I had a dog when I was a kid. What kid doesn’t love a dog? Then, when I moved to Detroit for my first teaching job, I lived with an aunt and uncle that had two dogs, a young, skittish Irish setter named Itty Bitty, and a doddering, incontinent Labrador named Joe. One barked; the other farted. Both incessantly. The experience cured me of living with dogs, an antipathy that deepened when I got married.

But these dogs, the walking dogs, are casual acquaintances we look forward to seeing. We know their names; we do not know their owners’ names. Today we might see Evvie and Snoopy, two rescue hounds with velvet ears and baleful barks; Bruno, also a hound who exudes confidence and would like to sniff and jump; Halley and Basil (rhymes with razzle), two youthful, powerful, slobbery Great Danes we do not approach; Max, a brown dog of a pugnacious breed, who happens to be deaf or blind. I think its owner told us which. I’m also a little deaf, and becoming forgetful.

And Echo.

Echo sleeps on the driveway, next to his garage. The last few years, if we got his attention, from his prone position he would emit a wheezy bark in our general direction. His collie mouth would open and close once or twice. Now, all is silence. My wife calls to him from the road. Hey, Echo. Hey, be-be. If he sees us, he nods his head. Some mornings the lady owner sits on the front porch. He was a rescue dog, she says. He was wary and fearful, then gradually became timidly companionable.

One day, she walked him down the driveway to us.

“He doesn’t walk much now,” she said. “I have to help him.”

“Echo,” my wife said. “Hi, be-be.” He stood still. We patted his beautiful head.

I learned to play the guitar in junior high. I never learned to scream. You could come home after school and practice the guitar, and remain, shall we say, unobtrusive. You could not come home from school and practice screaming. I’m working on my scream, mom. It’s not anger or despair, it’s music. Nobody I knew in the garage band culture I was part of was capable of an authentic, persuasive scream. Through the 60’s and early 70’s I heard screams I admired. Paul McCartney in “Can’t Buy Me Love,” Alice Cooper’s vocal-cord-shredding scream in “Elected,” Roger Daltry’s long affirmative scream in “We Won’t Get Fooled Again.” In “Let it Ride,” on the song’s exit, Bachman Turner Overdrive’s Fred Turner lets loose a howl-shreik-scream that still gives me goosebumps. In Pink Floyd’s “Be Careful with That Ax, Eugene,” continuous blood-curdling screaming is interrupted only when the screamer, a woman, takes a breath.

It occurs to me that a musicologist might undertake a research project. Call it scream studies. When, in popular music, did screaming begin? As far as I know, Frank Sinatra and Andy Williams, Judy Garland and Rosemary Clooney did not scream. Not once. So: Who screamed the first scream? In what years did screaming increase? Was race a factor? (Consider James Brown, Wilson Picket). What about gender? (Enter Janice Joplin.) When did screaming wane in popular rock? Did British rock groups scream more than American groups? In what part of a song did screaming most commonly occur? Informal observation suggests between the second and third verse, but that’s just me. What the world needs is a database. We need rigor.

A few years ago my son-in-law and I went to a local club where we thought we were going to see and hear big band jazz. Wrong night. The band played hardcore punk. The lead singer screamed so much, I got a sore throat listening.

“I’m afraid of what we’ll find,” my wife says.

We’ve just passed Lillian’s house, a friend who stopped her car the other day, put down her window, and told us she was a grandmother. “We have a baby girl,” Lillian said. We stood and talked. Her name is Suzanna June.

Traditional names are in these days. Especially boys. Charley, Jack, Gus, Sam, Henry. For girls, I think, not so much. Norma, for example. Or Hazel. I’ve yet to meet a little Hazel lately. But Suzanna June, wow.

Or was it June Susanna?

After Lillian’s we come up the hill where Echo lives, where we should see him lying on the driveway at the edge of the garage.

“What was it,” I ask my wife, “June Suzanna or Suzanna June?”

“Do you see him?”

I don’t see him. “Maybe he’s inside today.”

“He’s never inside,” she says. “He likes the cold. That’s what she told us. Echo likes the cold.”

We stop for a minute at the bottom of the driveway. No Echo.

“Not today,” I say.

“He’s gone.”

“Maybe not.”

The sun is coming out. We resume our walk. At the bottom of the next hill we usually see Max, who totally ignores us.

“I hope it’s Suzanna June,” I say.

“What?”

“Lillian’s grandbaby. It sounds better. It’s iambic. Suz-ann-a June.”

Not June Suzanna. Like Ole Suz-ann-a, it’s trochaic. Pine Tree Trail. Red Rose Tree. June Suzanna.

I drape my arm around my wife’s shoulder and hum “I Wanna Be Your Man.” It comes to me unbidden. I can’t help myself. Thinking, as I hum, she just might scream. I ask her: “Am I your man?”

A short pause. “Yes.”

“And you’re my woman.” I punch the first syllable. Wo-man.

She slips an arm around my waist. Says I am such an ass. Well, that’s good.

November 2, 2023

Comfort, Comforter, Comfortest–from American English, Italian Chocolate

“Help me with the piumino,” she says.

My wife is holding an armful of comforter cover, still warm from the dryer. We’re going to stuff the comforter (piumino in Italian) into the cover, an ordeal that makes me long for the simple days of my youth, when bedding consisted of flat sheet, blanket, and bedspread.

Ordinarily I like things ending in -ino and –ini, a diminutive Italian suffix that confers cuteness on just about anything. Even a turd—stronzino—becomes adorable in the Italian diminutive. I do not love the piumino.

“Must I?”

“Yes, you must.”

The problem is fit. We have an oversize cover. It’s too long, it’s too wide, the comforter floats around inside like a slippery manta ray as we pinch it, feeling around for edges, trying to trap it approximately centered. It is a doomed effort, which means eventually either the lower or upper region of our bed will have lots of comforter, capable of achieving incubation-level temperatures.

“I hate this thing,” I say.

“It’s easier.” She’s standing on a chair at the foot of the bed, getting ready to fluff the comforter. “You center it, you poof it, and you’re done,” she says.

“You’re standing on a chair to make the bed. That’s easy?”

“Yes.”

“I hate this thing.”

Martha Stewart looks down on me with that confident smile of hers. She’s wearing pajamas. “It’s already decided,” she says. “You’re getting a comforter.”

She fluffs the comforter, parachuting it to the mattress. It takes three or four poofs to get the job done. She climbs down from the chair, says it looks nice. She likes it.

Does she ever. She likes it so much she even leaves it on our bed in the summer. All summer I toss the thing off me all night long. All night she tosses it back on. Some mornings I wake up feeling like poached sole.

I’m pretty sure I was not yet out of primary school when my mother taught me how to make a bed. I learned to execute hospital corners on both the top sheet and blanket, then smooth a bedspread over the whole, finishing with a crisp tuck under the pillow. Comfort then was measured in footpounds of blanket weight you felt piled on in the winter, the heavier the better. If you had feathers, they were in your pillow.

The dispute comes down to your feather orientation: feathers on the bottom as opposed to feathers on top.

History suggests humans are originally, and through much of recorded time, feathers on the bottom. Feather beds date back to the 14th century, though a rarity, primarily comforting the well-to-do. By the 19th century, however, they were more common. The feather “tick” also made its appearance at this time. It was essentially a linen or cotton bag full of feathers (50 pounds of feathers!), which was then laid over a mattress. You would lie on the tick, not pull the tick over you. God was in his heaven, and all the feathers were beneath us.

My wife took me to Macy’s the other day, more for company than for my opinion. We went sheet and comforter shopping. This stuff will go on her parents’ bed in Italy, a bed we now sleep on a couple months of the year. It is an instrument of torture.

Not, evidently, on the continent, where the duvet was becoming a thing, popularizing the feathers-on-top orientation. The term duvet, meaning “down,” dates back to 18th century French. Samuel Johnson, in 1759, refers to with skepticism to an advertisement for duvets, noting, “Promise, large promise, is the soul of an advertisement,” citing, as an example, “‘duvets for bed-coverings, of down, beyond comparison superior to what is called otter-down’, and indeed such, that its ‘many excellencies cannot be here set forth.’” Johnson, something tells me, did not swing that way.

Mattress historians note that right-thinking Brits and Americans clung to their feathers-on-the-bottom orientation until well into the late 20th century. In the 1970’s, duvets began to appear in department stores in England; in 1987 Ikea opened its first store in London, marketing comforters as “doonas.” That was that. Today, according to The Daily Telegraph, department stores sell seven duvets for every blanket. The Telegraph reports, “Argos, the country’s biggest furniture retailer, does not even sell woolen blankets. Fleecy little throws from man-made fibre, yes, but not a proper, woven piece of Britain. It stocks over 100 different duvets.”

My wife took me to Macy’s the other day, more for company than for my opinion. We went sheet and comforter shopping. This stuff will go on her parents’ bed in Italy, a bed we now sleep on a couple months of the year. It is an instrument of torture. Until recently its wool-stuffed mattresses rested on a bouncy, noisy wire mesh that over time had become fatigued and taken to sagging in the middle. The lumpy mattresses also sloped toward the center, creating a kind of culvert in the middle of the bed. These mattresses were heirlooms to her, pieces of family history she wanted to preserve. She said they just needed to be fluffed.

Fluffed? I pictured us hanging bedding out the window and pummeling our wool mattresses, punishing them for hurting us. Instead, we are now rehabilitating the bed. The wool mattresses are history. The mesh is next.

But it looks like there will be a comforter.

While I wait beneath a Martha Stewart poster at Macy’s, my wife tests sheets for crispness. She looks at Westport 1000 thread count, pronounces it slimy; Genova 1200 thread count, slippery; then there’s Bentley 400, Charter Club Opulence 800, Ralph Lauren RL 624 Sateen, none of them quite right. She says she wants them scratchy. She skips the sheets and moves to comforters.

Martha Stewart looks down on me with that confident smile of hers. She’s wearing pajamas. “It’s already decided,” she says. “You’re getting a comforter.”

“I know that.”

“You know what else is nice,” Martha says, “for accent?”

“I like the scratchy sheets. I’ll give her that.”

“Shams.” She flashes me her Martha smile. “Lots of shams.”

“No.”

“King or queen?”

“Queen. No shams.”

“In a variety of sizes,” she says, “you can fit up to a dozen pillows on your bed.”

My wife steps up to the register, motions me over. She’s picked out a comforter cover. “The comforter,” she says, “will be a special order. Is that okay?”

It’s not. It’s really really not. But I tell her, “Of course, that will be fine.”

October 23, 2023

When We Went Hither–and what we swore

“Don’t even think about it,” Tizi said.

We were walking down to the local market the other day, a two-mile round trip on foot. It was a bright morning in October, perfectly autumnal. I was telling her about a professor of mine who used to say au-TOOM-nal, a pronunciation I liked and tried on for a while, only to be interrupted and told to say au-TUM-nal instead. I looked it up. Au-TUM-nal, said the dictionary. So the TOOM was idiosyncratic. Still, I thought it seemed poetic and would return to it occasionally for effect.

“What do you say?” I asked her.

“Au-TUM-nal.”

In places the sidewalk was spotted with rotting walnuts, which meant we walked single file at those points, dodging the black smears under foot.

Well I was thinking about it.

It was a simple question. We’re getting older. We walk to the market and back to stay young, but it’s not really working. We’re still getting older. Eventually, we will be old. We’ve been married a long time. What if, I wondered, a few years from now, when we arrive at our 50th wedding anniversary, we celebrate it with an exchange of vows?

And she said, “Don’t even think about it.”

“Once was enough,” I said.

“It worked, didn’t it?”

I thought about it last Saturday, at Anthony and Allyson’s wedding. Like ours decades ago, it was an Italian Catholic wedding. Unlike ours, their processional was Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” a tune anyone would recognize, stately, dignified, played on the church organ much too loud; a piece of music I like even more now that I know the title. Man’s desiring. Hell yeah. What was the processional at our wedding? I do not remember. I do remember Tizi was adamant–she is almost always adamant–that there would be no Here-Comes-the-Bride at her wedding. (Note the possessive pronoun.) Somehow we got down the aisle, to what music I don’t remember.

Then Anthony and Allyson vowed the conventional vows. I, Anthony, take you Allyson… What were our vows? I do not remember those either. After vows and communion, Anthony and Allyson exited to the music of Henry Purcell’s Trumpet Voluntary, again easily recognizable, played on the roaring organ. It was grand, triumphant. At Tizi’s wedding I would have been happy with the traditional Mendelssohn exit with its big organ fanfare. Corny, I know. But you only get married once. Theoretically, at least. Tizi was adamant about nixing that conventional There-Goes-the-Bride exit, da da dah-dah da da da. We retreated up the aisle to the tune of “God’s Blessing Sends Us Forth.”

It was a good send-forth, I admit. We’ve lasted.

Since then, especially in the last twenty years, as we’ve grown together, at every wedding we attend, when the couple exchange vows, I feel myself sinking into a slough of unashamed sentimentality. Sometimes I reach for her hand, which she will hold and lightly squeeze. It’s more than humoring me. It’s a sincere squeeze. We listen, and I feel a twinge of regret, baffled at the memory gap. What did we say?

“Do you remember our vows?” I ask her.

“No.”

“Doesn’t that bother you?”

“No.”

“I wanted to plight my troth. Didn’t you want to plight your troth?” True to form, she does not respond to my nonsense. I don’t blame her. But that solemn language. Those joyful, solemn, forever words that you remember. We never said them.

Right now she’s a few feet in front of me. We’re almost to the market. She points at the fallen walnuts, both green and black, at the edge of the sidewalk and says, “It looks like someone swept here.”

Since then, especially in the last twenty years, as we’ve grown together, at every wedding we attend, when the couple exchange vows, I feel myself sinking into a slough of unashamed sentimentality.

It was the priest’s fault. We sat across his desk from him in the rectory office. “A lot of couples these days,” he said, “are writing their own vows.” We must have shrugged. “Or–,” he pointed at the red book on the desk–”or you can just go the conventional route.”

It was 1977. The sunshine of the 60’s still shone upon us. There were garden weddings, river bank weddings, meadow weddings, along with oddball ceremonies, sky diving and scuba diving and mountain climbing weddings. In our case, there were distinct family expectations. I’m sure it happened, but we didn’t know of any Detroit-area Italian Catholics who got married in a corn field. Besides, it was November. Ours would be a very conventional St. Ives ceremony, San Marino Social Club reception wedding.

But the vows. Sitting there in front of Father Grandpre, I looked at Tizi, she looked at me, and we thought, Well, yeah. We could write our own vows.

We had just finished “marriage encounter,” a workshop for soon-to-be newlyweds offered by–in some parishes required by–the Catholic Church. Think driver’s ed–rules of the road, important road signs, how to avoid fender-benders and head-on collisions. We were in our mid-twenties, arguably still babies. The workshop intended to address our knowledge gap. It was hosted not by a priest but by a deacon, who was married himself. He and his wife and five volunteer couples, ranging from newly married to old experts with 35 years of accumulated wisdom, conducted 4-5 sessions for six candidate couples, on topics such as how to communicate, how to resolve conflict, how to share, how to compromise, how to be sexual. How to be faithful, both to the church and to each other.

The basics: How to stay married.

(In the years after, two of those couples, those with the least and those with the longest tenure, were divorced.)

We graduated a few weeks before the ceremony. In the days that followed, we went down the get-ready checklist–rsvp’s, tables and seating and centerpieces, clothes, shoes, flowers, hair, rehearsal dinner menu, reception menu, beverages, ceremony music, music at the reception. There was the issue of what Tizi called bomboniere; when I didn’t get that, what she called favors; when I didn’t get that, what she called little presents to lay on the table at the reception for women who attended the wedding. Not a convention in the small-town, mainly Protestant weddings I had attended. I was learning.

We didn’t forget about our vows. We just actively put the issue out of mind, thinking perhaps: We’ll trust inspiration. Trust love. Rely on spontaneous eloquence in the moment.

When the time came, when the priest held a microphone in front of my face, standing there in front of the altar I babbled something in the promissory mode. Then it was Tizi’s turn to babble. I remember none of her words either, except for her saying near the end of her vows that she would give herself to me, all of herself. A short silence followed. She had run out of inspiration. That all really stood out, for me and for all to hear. I felt my ears getting warm, probably turning a little red. Of course I wanted her, I wanted all of her, just not in front of 100 people, and especially not in church, and not in front of a priest.

#

Troth be told, the language of wedding vows lends a kind of majesty to the proceedings. They are old words, dating from the 11th century. A sample:

Behold, brethren, we have come hither in the sight of God, the angels, and all his saints in the presence of the church, to join together two bodies, of this man and of this woman…that henceforth they may be one in flesh and two spirits in faith and in the law of God, at the same time to the promised eternal life, whatever they have done previously.

So sayeth the priest. Behold! we have come hither. Hither! We’re not just stopping by to get hitched. We have come hither.

And, seeing it now, I really appreciate the “whatever they have done previously.” Your wedding day was a day of grace, a plea bargain, a reduced sentence. Get into heaven free.

Even to this day, ceremonial wedding language sounds much like the above. Back then, the man and woman about to be officially joined uttered these words:

I (Name) take thee (Name) to my wedded husband, to have and to hold, from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to be bonnair and buxom, in bed and boord [board? ] till death us depart, if holy Church will it permit, and thereto I plight thee my troth. (my emphasis)

And there we go. “And thereto I plight thee my troth.” I wish I had said that.

And wouldn’t the grooms of today love the “buxom in bed and board” part? They said that in church? Though further inquiry reveals that back then those words pertain to obedience, “to behave properly and obediently through night and day.”

In 1549, with the Protestant Reformation, that ceremonial language, from the 11th century Sarum Rite, based on the Catholic liturgy in Latin, became part of the Book of Common Prayer, informing wedding tradition in the English-speaking world for the next 500 years. It’s the language I heard at every wedding I attended, from childhood into adulthood. Till death do us part.

Then Rick and Tizi rewrote the script.

In contemporary times we are not big on oaths. I can’t remember the last time I was asked to swear an oath. On a passport application? But I didn’t actually swear it. I read it, I thought it, I checked a box on the State Department website.

I learned the pledge of allegiance in elementary school. That felt like an oath. A few years later I memorized and recited some tidbits of Boy Scout law, “a scout is thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent…” Actually not an oath, but it’s oath-ish. A boy in church, I recited the Apostles Creed. In Methodist confirmation classes with Mrs. Hilton and Mrs. Bell, I memorized the 23rd Psalm, Revised Standard Version, with its thys and thous and verbs ending in -est (thou anointest my head with oil? Ew, but cool). Solemn stuff. In the ninth grade, I memorized the Gettysburg Address in civics class with Mrs. Davison. I thought I might swear an oath when I got my driver’s license. Q: Dost thou know how to drive? Wilt thou obey the law? Stop at all stop signs? A: Verily I do promise to do so.

Short of being brought up on charges (Do you promise to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth…), we have little opportunity to swear an oath these days. Maybe less is more.

After their vows, before the Trumpet Voluntary processional, Anthony and Allyson were pronounced man and wife–not husband and wife or man and woman–and introduced in the church as Mr. and Mrs. Anthony Monaco. At their reception, it happened again. The leader of the band invited us to put our hands together, to make some noise, he said, for Mr. and Mrs. Anthony…” An asymmetry embedded in the language, still embedded in our culture.

We didn’t forget about our vows. We just actively put the issue out of mind, thinking perhaps: We’ll trust inspiration. Trust love. Rely on spontaneous eloquence in the moment.

I asked a local monsignor one time, after he’d officiated at a wedding we attended, when they had stopped saying, at the end of ceremony, “What God has joined, let no man put asunder.”

He looked at me, bewildered. “We never said that.”

Someone said it. I had always heard it. He shook his head. “You’re thinking Anglican, or you’re thinking Protestant. Those words are not part of the Catholic ceremony.”

When’s the last time, the last wedding we attended and I heard those words? “Let no man put asunder.” I now know they were not said at our wedding. They should have been.

#

Half our walk home from the market is uphill. Yea, I say unto you, the path of the righteous and the wedded is sometimes uphill. We always walk the same route there and back, a foolish consistency. We shop light at the market, only one or two items. The shopping is an excuse to go for the walk. This morning I carry a pound of ground turkey, a low-fat meat we eat in the interest of longevity. If we have to get old, we would like to do that together.

I ask Tizi, “I wonder if Anthony and Allyson did the garter and bouquet toss.”

“Don’t tell me you’re still thinking about that.”

“I’m still thinking about that.”

We did it. Everyone did it at their wedding back then, almost 50 years ago. At our reception, after dinner, after the toasts, relatively early in the evening, the Bill Meyer band played some woozy, jazzy striptease music while I knelt in front of Tizi seated in a chair on the dance floor and reached under her gown for the frilly garter she wore on her right leg. I then tossed the garter in the direction of unmarried men, and she then tossed her bouquet in the direction of unmarried women. All part of the fun, with historical antecedents and symbolism. The bouquet, the deflowering. The garter? In weddings in 18th century England, they played a game called “flinging the stocking.” Further back in history, family and friends actually accompanied the couple to their bed on their wedding night, where the newlyweds were expected to consummate their union. That would be a bit much.

We’re in the walnuts, single file. I say to her back, “I don’t suppose you would be up for a garter toss on our 50th.”

“Please.”

It’s all just a thought experiment. We’ve lasted this long. Do we really need to plight our troths? I need to let it go. What God has joined, let no man–especially the groom–put asunder.

October 13, 2023

Beans and Baroque

Georg Philipp Telemann

Georg Philipp TelemannThis morning I have a pot of bean soup on the stove. These are pinto beans. We buy them still in their pods at a local grocery store. Tizi is obsessed with them. Whenever we find a basket full of pinto beans, she buys them all, carrying out a whole shopping bag full of them in their mottled pink and white jackets.

Back home we shuck beans at the kitchen table. Sometimes I help, because that’s a lot of beans. Also because it’s a pleasure to do the work together. Also because I really like the word “shuck.” Shucking beans is a silent, manual activity. That many beans takes us a half hour or so, grabbing the top of each bean by the stem and pulling it down the length of the pod, inserting an index finger into a gap and sliding it up or down, popping the beans, 4-6 of them, out of their pod and into a stainless steel bowl.

“More than we can eat,” I’ll say.

“We can freeze them.”

I’m a proponent of just-in-time grocery shopping. The idea of food stored long in the freezer, especially beans, doesn’t agree with me. Anyway, aren’t beans supposed to be dry?

“Aren’t beans supposed to be dry?” I ask her. “Should we dry the ones we’re not going to cook?” It occurs to me that I don’t know how we would dry beans. Leave them on the kitchen counter? Put them in the oven? In the dryer? On the table, four bags of them are shucked and ready to freeze. “Four bags,” I say. “I mean, pretty soon our freezer will be a bean locker.”

“Don’t be silly.”

We freeze them. Next trip to the store, if she sees them, the process plays out again.

This morning’s soup is pinto bean, onion, a leftover chicken leg-thigh that I baked yesterday, the meat stripped from the bone (the technical term, I guess, is “jerked”), diced and cooked first in olive oil with a splash of white wine, then in added chicken broth from a box. I would say it’s chicken chili, but I hold the cumin, which I feel is tragic. Tizi doesn’t like cumin. Instead, I add fresh rosemary.

After I stir the rosemary down into the soup, the broth just over the surface of the beans-onion-chicken, I tap the wooden spoon on the edge of the pan. I tap it to the rhythm of La Cucaracha, 1-2-3 4 5.

After every stir, I tap to that rhythm. I don’t know why. It just feels right.

Our response, our inclination to be rhythmic beings, must be part of our DNA.

Long experience has taught me that I do not have great rhythm. I’m a clumsy and leaden dancer. But the older I get, the more I connect with percussion in music I listen to. Anyone playing drums behind Sting, for example. Mitch Mitchell on early Jimi Hendrix LP’s–on “Fire,” for example, those stacatto triplets and stuttering pistol shots on the snare, drumming so intense I feel exhausted just listening to the song, all 2 minutes 30 seconds of it. Ringo Star on “Taxman,” again the snare, his rolls of fives–fiplets?–before the chorus–and “Come Together” (the latter of which I recently read Mr. Star regards as his favorite song in the Beatle catalog); Paul Simon’s “Rhythm of the Saints,” echoes of the jungle, of forested hills in Brazil.

I could never drum. But In the kitchen, with a wooden spoon in my hand, I play La Cucaracha.

Music and memory are my friends. I live by them. I live in them. “Music and dance,” Dan Falk writes in Knowledge Magazine, “are so deeply embedded in the human experience that we almost take them for granted. Without knowing it, we track pulse, tempo and rhythm, and we move in response.” Our response, our inclination to be rhythmic beings, must be part of our DNA. My friend Chuck has been leading African drum choirs in Atlanta for years. In the case of both kids and adults, he says drumming and rhythm unlock something inside them, a pleasure center, from far back in human history, that’s expressive and satisfying.

#