Lise Deguire's Blog, page 7

May 21, 2021

"I Can't Imagine: What NOT to Say to Someone Who is Grieving"

Guest Blog by Caryn Anthony

I am honored to publish this beautiful piece by my dear friend, Caryn Anthony, about loss and how to truly connect with people who are grieving. If you have ever worried, "But I just don't know what to say to her," this piece is for you.

“I can’t imagine…”

I have heard that phrase countless times in the last several years since the death of my son Robby. I know people mean well when they say it. They are trying to acknowledge the depth of my loss, and they intend to show compassion, even respect for what it takes to face and endure such pain.

Still, sometimes I’m frustrated by the expression because I know it’s not really true.

After all, haven’t most parents tapped similar fears in their own imagined worst-case scenario? You know the thoughts… Your daughter should have been home half an hour ago – was there a car accident, an alien abduction? Or your son has some unexplained pain or a fever that won’t break – is it just a passing thing or the beginning of something serious? If you’re lucky, everything works out, and you can shake off the images like a fleeting bad dream.

But sometimes, there is no avoiding that terrible place, as we hear in the song “It’s Quiet Uptown” from Hamilton:

There are moments that the words don't reach There is suffering too terrible to name You hold your child as tight as you can And push away the unimaginable

So, if someone says, “I can’t even imagine…”, what I also hear is, “I don’t want to imagine. It is too scary for me to go there. “

I found unexpected dark humor in this dynamic watching Netflix’s “Dead to Me”. The main character’s husband has died in an accident, and her neighbor says, “I can’t even imagine what you’re going through!” The new widow stares back coolly and replies, “Well, it’s like [your husband] died suddenly and violently. (Pause with exasperation) It’s like that.” The thud of that awkward moment is grimly hilarious, and illustrates the typical discomfort people like me encounter as others contend with the blunt facts.

In my own reality, I used to describe myself as every parent’s worst nightmare walking around. And while it sounds facetious or dramatic, I wasn’t really kidding. My son died after several years of relentless advocacy by loving parents, world-class medical care, and his own brave fight. So, my family was an unwanted reminder that sometimes the worst does happen, despite everyone’s best intentions and efforts. That is not a reality most people want to confront…

For me to work through this, I need the support of someone who can imagine this reality or at least is willing to try.

I don’t want to inhabit some foreign territory far, far away from what my loved ones can imagine. I want you sitting here next to me. Loss and grief are wrenching and life-changing, and they are also unavoidable. At some point everyone will be forced to confront the mortality of a loved one, and I’ve learned that you don’t “get over” loss like that. You make room for it in your life.

I realize that this truth about grief can be uncomfortable. Many want to believe that the pain can be overcome or at least avoided. Unfortunately, that is not how it works for me – Robby’s presence permeated my whole life, so reminders of him are also ubiquitous.

I may smile and shed a tear when I hear Queen on the radio, or I watch our favorite zombie television show, or even smell the French fries from his favorite burger spot. As unsettling as these moments can be, I’ve discovered that they are also precious because they help me feel closer to him.

The poet Kahlil Gibran said:

“When you are sorrowful, look again in your heart, and you shall see that in truth you are weeping for that which has been your delight.”

So, please don’t worry when you see me react. Don’t change the subject or try to cheer me up. My most trusted people are those who understand that this is now part of who I am, and they are in it with me. Instead of being afraid of “reminding me” of something sad, they openly share memories and feelings, and they keep Robby present for me when they say his name.

My capacity to come through this loss is built on finding ways to live with, and sometimes even welcome the unimaginable. And the resilience isn’t just something intrinsic in me – it’s something that grows with the support of people around me. I lean on others who are brave enough to see reality and are ready to stand with me in all the feelings.

There’s no special training required – just show up with your presence and compassion. I want you to ask questions and to listen to the real answers, to laugh and remember the joy, and sometimes to just sit quietly beside me as I live with the unimaginable.

I appreciate Lise’s invitation to join as a guest blogger here, especially because Lise and her family remain a beautiful example of the support I did and still cherish. The shared experience deepened our friendship – now going on 40 years! – to a place that is rich and enduring.

If you’d like to follow Caryn’s writing about the intersection of parenting and caregiving and grief, you can check out her blog “Any Way the Wind Blows” here: https://canthony.medium.com/

Lise Deguire's gold award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

May 7, 2021

What Daily Meditation Can Do For You

“Peace. It does not mean to be in a place where there is no noise, trouble or hard work. It means to be in the midst of these things and still be calm in your heart.” Unknown

I began the morning with a meditation. After taking my dog out, and brewing the coffee, I sat in my sunny living room, my little dog Frankie nestled beside me. I perched cross-legged, a blue pillow on my lap for warmth. I closed my eyes and began to focus on my breath.

When ten minutes passed, I raised my hands in appreciation. “Thank you for this day. Thank you for my family and for our health. Give me strength, wisdom, and love.” Then I extended my hands forward, “So that I may give strength, wisdom, and love”. Finally, I stretched both arms out sideways, wiggling my fingers in my peripheral vision, a reminder to be fully aware. This is how I start every day.

It wasn’t always this way. My older brother Marc tried to get me to meditate when I was 14. Although he was a patient teacher, I didn’t understand the point of the exercise.

“Let’s sit together. Close your eyes and concentrate on your breath.”

“Why do I have to do this?

“Just sit, Lise. It’s good for you to learn. We will do it together.”

“OK, but why?”

Marc tried, but I resisted. I stopped meditating as soon as he went back to college.

Years later, as part of my psychology training, I took classes which touted meditation as a stress-reducing technique. During the classes, there were demonstrations which I always enjoyed. I sat back, breathed deeply, and felt a deep flow of relaxation inside me. But, back home, I had no follow through. Once the classes were over, so was my meditation.

My breakthrough into daily meditation happened in 2020, one of the few good things that arose from that dreadful year. I was home, virtually every minute of my life. I didn’t have to dash from of the house, brave traffic, and arrive at the office by 9:00. Mornings stretched more languidly. It was easier to find those ten minutes to breathe every morning.

Now I sit every day. I scan through my body, noting points of tension, areas of pain and pressure. Simple awareness of the tension shifts any pain, and my body settles. My mind, free from my constant to-do lists, drifts along, as if floating on the waves of a gentle sea. I hear the sounds of the house around me, the heater outside, working mightily to warm our home; Frankie the dog beside me, sighing. My stomach muscles unclench. I notice thoughts drifting in. I don’t attend to them. The thoughts fade away. Peace.

Of course, that’s when meditation goes well. Sometimes every minute slogs on. My scalps itches. “I forgot to return that phone call,” I think, and my body tenses into high alert. “Oh no, I have to write that woman back!” My throat tightens. “What if that editor doesn’t like my submission?” My stomach jams into a knot. I cannot let these thoughts go. “I suck at meditation. Why can’t I just breathe? When will these ten minutes be over?”

Sometimes meditation goes like this. It isn’t always peaceful and it doesn’t always feel good. The key, I’m told, is to keep at it. Like any skill, the more we practice, the better we get at it. It is no accident that we say one “practices meditation.” I didn’t get decent at writing in one year either.

If you are like the 14-year-old me, you might be asking, why meditate at all? There are so many benefits I don’t even know where to begin; here is a partial list. Meditation…

- Soothes anxiety: When you learn to focus the mind, your thoughts don’t spin off into anxious “what-ifs,” spiraling into anxious ruminations.

- Calms anger: Focusing on breathing calms the mind, stopping our internal tirades over people who have wronged us.

- Improves the immune system: The body is not designed to be in a constant “fight or flight” mode. When we are tense, our immune system works poorly. When we relax, our immune system resumes its work.

- Lowers blood pressure: Meditation is a proven technique for improving hypertension.

- Manages emotional reactivity: This is a big one. It is easy for me, sensitive soul that I am, to feel hurt and wounded by other people. Meditation allows me to detach from the provocations of the moment, and to tap into inner peace. Once I have calmed myself, I find freedom from reacting emotionally. I can bring more thoughtfulness and wisdom to my relationships.

Happily, the benefits of meditation extend past the ten minutes into the whole day. Now that I practice regularly, I notice when my shoulders leap to attention. With mindfulness, I can lower those shoulders down. I notice when my stomach tenses up, and I can breathe that tension away. I notice when my mind anxiously swirls around my to-do list and I can tell my mind to relax. The awareness that comes from a regular ten-minute mediation follows me throughout my day, helping me stay calmer and more serene.

Here is a story: A while ago, I was getting ready for a radio interview, as part of my recent book promotion. I had an hour to spare, and I thought I’d make a quick phone call to an insurance company. This “quick” phone call dragged into an infuriating 40 minutes. I was on hold, listening to inane music, on some incessant torture loop. Finally, the customer service rep came on but we had with a terrible connection. I could barely hear her, as she was undoubtedly on another continent, and I couldn’t understand her either. After a brief exchange, which I barely fathomed, she declared she couldn’t help me. I got off the phone in disgust.

“I’m so aggravated! I just wasted an hour on the phone with this stupid company and now I have an interview in 15 minutes. What a colossal waste of time! I have this radio interview and I am so upset I can barely think!”

My husband gazed at me. “Why don’t you do your meditation thing?”

I glared at him. I really just wanted to righteously complain. But my husband was right; I was a wreck.

I sat in my bedroom and closed my eyes, focusing on my breath. Immediately I sensed my body’s distress. My heart rate was elevated. I breathed rapidly. My shoulder were raised and my stomach was in spasm. “My god,” I thought, “My body is completely dysregulated, all from one stupid phone call.” Quietly, I focused. I felt my muscles relaxing and my heart rate slowing. I ended the meditation, feeling like a different woman, and started the interview with a smile on my face.

That is the power of a regular ten-minute meditation practice. Let’s be clear. Everyone, no matter how busy, has ten minutes to spare. You can do this, and build yourself a calmer, more peaceful life, in a healthier body. One final tip: it is best to find a regular time of day for your meditation practice. Do your breathing every morning, or every bedtime, or every evening after work. Otherwise, you will keep putting it off until later. If you are like me, you might even put it off for 40 years.

(Note: This post was republished with permission from tinybuddha.com. You can find the original post here: https://tinybuddha.com/blog/how-10-mi... )

The author's gold award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

April 23, 2021

Finding Compassion in Unexpected Places

Guest blog by Carol Campos.

I am honored to publish this beautiful piece by Carol Campos about love, addiction, co-dependency, recovery and healing. Awhile ago, Carol hosted me on the podcast, The Divine Breadcrumb, where we had a moving and deep conversation (https://thedivinebreadcrumb.com/podcast/podcastDetail.cfm?pcID=91). I am thrilled to host her in return.

I always assumed I would be a mom “someday,” but I never thought about what the circumstances would be when that time came. I guess I figured I would be married and living in my first home. That’s how it works, right? But I chose to marry someone with a drug problem. That’s right-I knew he had a drug problem, but married him anyway. I couldn’t have imagined how it would turn out. In my naïve mind I believed that if I loved someone enough, they would change. The harsh reality was something I was neither prepared for nor equipped to deal with. However, as hard as this story is to tell, it undoubtedly helped shape me into the person I am today.

I met my ex-husband shortly before graduating high school and we dated on and off while I was in college. He didn’t become an addict until I was in my senior year of college. I didn’t realize this at the time because I only saw him on breaks. Occasionally he would make the trip from MA to NY to visit. Our visits were brief so it was easy enough for him to hide his addiction. But when we moved in together soon after I graduated, I started to notice some odd behavior. He would spend long periods of time in the bathroom and every once in a while, I could hear the flick of his lighter. At first, I didn’t think too much of it. But I noticed that he had become very moody and easily agitated. Very rarely did he seem happy. At this point I still didn’t have a clue what was going on, but I knew things were “off.”

But then, it seemed that each time he got paid there was an issue. There was a problem with payroll or “they” lost his check. I still wasn’t fully grasping what was happening. I just knew that when it came time to pay the bills it was all falling on me. It wasn’t until I found my own money missing that things started to click. But I didn’t want to believe it. Soon a ring my father gave me for my 21st birthday went missing. Then my camera, also a gift, went missing. I confronted him many times and he would fly into a rage. I didn’t know what to do. It was all so surreal and scary. I no longer had a sense of security.

I had known this man for 4 years as a kind, loving person. Where was that man? The person I was living with was a stranger. But the relationship continued and I became more co-dependent with every passing day. I even agreed to get married thinking that would make him happy. Things went from bad to worse. He stole checks and forged my name. We had mounds of debt. I was desperate and too ashamed to let my family know what was going on. I still thought that I could “fix” him and somehow control this uncontrollable situation before anyone else could figure out how dysfunctional it was. I distinctly remember thinking that if we had a baby, that would give him a reason to get better. Through my co-dependent haze, I saw this as a loving way to help him. In truth it was pure manipulation. But I honestly didn’t recognize this at the time. I thought I was being kind and compassionate and even had a twisted sense of pride about it.

When I did get pregnant, he was excited and happy (he loved babies) but nothing changed. It only got worse. We ended up losing our apartment and I went to live with his sister. His addiction was so bad that he was living (squatting) in various drug houses around the city. What should have been a time of great joy and hope for us as a couple ended up being anything but. Thankfully, the pregnancy was actually very easy and uneventful. But my own sickness of obsessing over him, where he was and what he was doing, escalated. Those were very dark days.

It was the summer of 1991 and I was 24. Each day I would go to work and before I could go back to his sister’s apartment, I would go looking for him in the drug houses. Can you imagine? Here I was, 7 months, 8 months, and yes, almost 9 months pregnant, wearing my cute maternity dresses traipsing around the worst part of the city, on a mission to make sure he was alive. What I was doing was dangerous and I didn’t even see it. I just knew that I couldn’t rest until I knew he was ok. After a time, the other addicts began to recognize me. Before I could even knock on the door, a nameless man or woman would come out onto the porch and say, with sadness in their eyes, some variation of: “You shouldn’t be here. You should go home and rest. Don’t worry about him.”

This would happen over and over. These people were incredibly sick, emaciated, dirty, didn’t have the proverbial pot to piss in and they were concerned about me. What they lacked in material possessions they made up for in pure compassion. But of course, I didn’t recognize that at the time. I silently blamed all of them for “keeping him from me” or “being a bad influence.” I would become agitated and instruct them to “go get him please and tell him I need to talk to him.” Sometimes they would plead with me a little longer to go home and other times, knowing that I wouldn’t leave, would oblige.

Twenty-eight years later, the summer of ‘91 seems like a bad dream—a dream that happened to someone else or a character in a movie. I have a beautiful daughter who is now a grown woman, thriving and happy. I am thriving and happy. Occasionally I think about that crazy, awful summer and how I played a part in the chaos and drama. Was I to blame for my ex-husband’s addiction? No, but I was responsible for my own behavior. It took years to forgive my ex-husband and to forgive myself for what happened that summer. I had to dig deep to find compassion, something that these strangers had so generously bestowed on me. Who could have imagined that it was possible to get a lesson in compassion from a group of strangers who I had held in such contempt? Each one was a Divine Breadcrumb, disguised in human form, steering me back to the light.

Today I strive to be an open, kind, and compassionate person and I also actively look for these traits in others. Sometimes it’s like digging for gold and not so easy to find. But I try to remember that the people we encounter are our mirrors. If I’m having trouble seeing the good in someone, that’s more about me than it is about them. That can be hard to swallow sometimes. But I’m a work in progress and I’ve learned that having compassion for myself is the foundation for everything else.

Carol Campos is a Life Strategist & Mentor, focusing on empowerment, awareness, energy & alchemy. She is also the creator & co-founder of The Divine Breadcrumb podcast & online community. Carol spent over 20 years in corporate, most recently at a Fortune 10 company. In her mentoring practice, Carol uses a combination of her extensive business experience and soul-aligned interests, resulting in deep shifts, healing & transformation. Carol provides her clients with practical tools as well as energetic tools to provide a complete mind/body/soul experience.

Dr. Lise Deguire's award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

April 9, 2021

How You Rocked One Terrible Year

It has been a year since COVID stopped us in our tracks...a year of loss, isolation and death... a terrible year. And yet. It has also been a year in which people somehow managed. A year in which we stayed connected, kept the stocks shelved, and kept many businesses afloat, against all the odds. Think of all the adaptions you yourself made this year, all the unprecedented ways you coped. As we mark a year of solemn loss, I would also like to mark a year of human adaptation and fortitude. With gratitude, let’s talk about all the ways people rocked this year.

Last March, as the world shuttered, I feared that I would lose my job, my psychology practice of 20 years. My work is seeing and talking to people. Clients shuffle in, anxious, sad, exasperated, or joyful. We sit directly across from each other. We smile, laugh, and cry, face to face in a smallish room. Sometimes voices get raised in anger or anguish. Previously, this office felt safely intimate. Suddenly, my office seemed like a COVID incubator.

“I will be lucky to survive this,” I worried. “I will try teletherapy, but how many clients are going to want that? Half at most?”

Dutifully, I emailed clients, offering the link for teletherapy, hoping for the best. I prepared for the first home session, far away from my office, wearing a clean shirt and a little makeup. I am no tech wiz. Could I do this? Could teletherapy actually help clients? I blinked at the screen, smiling when the first client came online. It was good to see her face again. “Can you hear me?”

“I can hear you. Can you see me?

“Yes!”

Despite my concerns, almost every client transitioned easily into teletherapy. They didn’t like it as much as being in person, missing the intangible comfort of physical presence. Still, there were advantages. Clients didn’t have to drive to sessions, so it took less time. Scheduling became a breeze as clients could easily see me during a work break. Plus, I got to meet some adorable dogs and cats.

Even in the darkness, there is light. Think of all the ways that people have adapted in this terrible year. Everyone has suffered, some immeasurably more than others. There has been egregious loss of life, on-going disability, economic despair, losses of business. In writing, I do not minimize this suffering. I’m not saying it’s been good. I’m not saying it’s been ok.

Still, people have been remarkable. Like the tiny shoots of tulips, currently poking up for spring, people found their way toward the light, feeling toward warmth through the blanket of despair.

Teachers pivoted on a dime, learning how to teach online. Lesson plans were thrown out and recreated. They worked valiantly to connect with students across the screen. They even learned how to simultaneously teach online and in person. My husband, director of a large continuing education (CE) program, cancelled 200 in-person workshops but quickly replaced them with 250 webinars. He and his staff executed this massive change in just a few weeks. Surprisingly, attendance improved. It turned out that people like doing their CE classes online.

Parents worked from home, completing their work while simultaneously supervising their children. And by parents, (forgive me, dads) I pretty much mean moms. Moms ROCKED this year. They managed to keep their jobs, often working into the night so that they could get their kids outside for a family bike ride. Working moms raised multi-tasking to a spectacular height this year.

Restaurants figured out how to serve outside. Tables were set up on sidewalks and alleyways. When winter came, some restaurants placed individual tables in their own igloo tents, so that diners could safely eat outside, warm and cozy, with no dangerous exposure to others.

Then there were the Zooming grandmas. Grandparents all over the country were unable to see their precious grandchildren for a year. Undeterred, they got online, downloaded a weird program called Zoom, and we all entered a whole new world:

(Grandma is on screen, mouth moving, but with no sound and only the top of her head visible.)

“Grandma, we can’t hear you. You are muted. Unmute yourself.”

(Grandma – looking a little confused, mouth moving and arms flailing.)

“GRANDMA, hit the unmute button on the bottom. Also, please adjust the screen because we can’t see you.”

“. . . OK, can you hear me now?”

“Yes, great, how are you Grandma, we miss you so much!”

(Yelling into the other room) “Bob, they can hear us. Bob! Bob! Bring me my coffee, OK? And did you check the mail?”

“Grandma, please stop yelling. Now we can hear everything...”

People adapted. It happened bit by bit. We went from isolation and fear to wearing masks and. . . figuring it out. We couldn’t go on vacations, so we planted rose bushes and finally repainted our kitchens. We couldn’t go to theaters, so we watched Netflix and finished jigsaw puzzles. We couldn’t meet with friends, so we Facetimed, or shouted pleasantly to our neighbors.

We cooked.

We walked.

We adopted dogs. (Dogs had the best year ever.)

We did our best to maintain hope and to lift each other up. When exhausted health care workers completed their hospital shifts, quarantined people banged pots out their windows in thanks. People serenaded nurses, singing arias off their balconies or playing their dusted-off trumpets.

When the vaccine first arrived, many people were skeptical. “I’m not getting that vaccine,” I heard from clients. “They can’t make me get it. I just don’t trust it.”

Undeterred, doctors and nurses signed up for the shot. The same health care workers, who had already saved us, now saved us again, demonstrating the safety of the shot by filming themselves getting vaccinated. Public opinion started to shift, and people adapted again.

“I can’t wait to get my vaccine. Why is it taking so long?” became the new refrain.

I know this has been a terrible year. Some people were reckless and uncaring about other’s health, inflicting great harm. All that is true. The optimist in me, the grateful me, wants to notice and remember all the people who did wonderful things and all the ways that we adapted. We got through this. No one had ANY IDEA how to get through this, but somehow, we did.

Happy 2021. Springtime is here and it is getting warmer and lighter every day. We aren’t out of the woods yet, but we are finding our way. And you rock.

The author's memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

March 26, 2021

Healing Through Pain

by Samuel Moore-Sobel, guest blogger

(I am honored to host Samuel Moore-Sobel, as guest writer for this blog. You can learn more about Samuel, and his book, Can You See My Scars? at the end of this post.)

The minute he entered the room, my doctor asked me, “Well, how do you feel?”

I sat in my first follow-up appointment after facial reconstructive surgery. The surgery lasted longer than I expected. I felt unsettled after the experience, in addition to my post-operative pain. Yet even with my doctor, I felt the need to please.

“I’m feeling better,” I said, telling him that the pain and discomfort had mostly subsided. The doctor wanted to look at the surgical site, so with gloved hands he began to examine the area under my nose. In surgery, he had removed a failed skin graft from this area to create a different scar in its place. Moments later, he pulled on my lip, examining my mouth. He seemed pleased with the progress and returned my lip to its resting place. He looked at the area around my mouth one more time for good measure. “I know you weren’t enjoying the synthetic feel of the skin graft,” he told me, before saying he hoped this operation would lead to a better outcome than the skin graft had.

I was not so sure. I was eighteen years old and this wasn’t my first surgery. In fact, I had experienced several surgeries before this one, all attempting to address the damage left by severe burns to my skin. With each surgery, I fell asleep on the operating table hoping that I would wake up with a brand new face. Each time, I was disappointed. My face still had scars. Even so, I wished that maybe this time it would be different.

The doctor assigned me some homework. He instructed me to spread a substance called Neocutis on my finger and massage the area under my nose for two minutes, twice a day. “Do it right before you brush your teeth,” he said. He placed his right hand above my face, taking his second and third fingers and digging into my upper lip. He then placed his gloved thumb on the inside of my mouth and moved his fingers in a circular motion. As he did, pain shot through my upper lip. The circular motion continued, and I let out a few groans as his fingers dug deeper into my skin. As the demonstration ended, the pain subsided, and the scar returned to its normal position.

As our appointment came to an end, the doctor told me it would take time for the swelling to subside—as long as 12 months. That will take forever, I thought to myself. I was tired of my face looking swollen. I dreaded the looks I knew I would receive once I went back to school. On the car ride home, I thought about the pain I felt while the doctor massaged the scar under my nose. I shuddered thinking about repeating the process every day.

But my pain transcended the physical. It felt emotionally triggering to look in the mirror, and even more so to touch the scarred areas on my face. It reminded me of the worst day of my life. Just a few years before, I had been hired for a day to move boxes and furniture for a man in my community. By day’s end, I had suffered second- and third-degree burns to my face and arms, all due to the explosion of a box. I wanted to forget everything that had happened to me. Yet my scars prevented me from forgetting. And every surgery felt like re-opening old wounds that had not healed.

Despite my misgivings, I followed the doctor’s orders. However hard it might be, I wanted to speed up the healing process. I was willing to do almost anything; all I wanted was to get my face back.

Per the doctor’s instructions, I massaged the scar once again that night. The more I massaged, the more it hurt. After two minutes were up, the most curious thing happened. Even though I experienced pain while massaging my face, the area felt better when I was done. Over the next few days, the affected area began to feel more mobile, and eating became less of a chore. Soon enough, I was no longer in pain when I spoke. After a few weeks, I felt as if real progress had been made. I wondered if perhaps my face could be restored after all.

Little did I know that my journey was just beginning. It would take several more operations before I came to have the face I have now. It would be several years before I felt comfortable with my appearance. It would be several years before I could finally stop fighting my scars. It took longer than I could have anticipated to finally accept that I was never going to get my face back, no matter how hard I tried.

I learned an important lesson while desperately trying to restore my former face. Pain in the short-term can lead to long-term healing. Pain was no longer something I needed to fear, but rather something to face head-on. Pain in the present was not an indicator of pain in the future. Life could get better, if only I could handle the pain along the way.

Pain is an unavoidable part of the human experience. Perhaps pain isn’t something to be avoided, but rather embraced. After all, as Theodore Roosevelt said, “Nothing in the world is worth having or worth doing unless it means effort, pain, difficulty… I have never in my life envied a human being who led an easy life. I have envied a great many people who led difficult lives and led them well.”

The face I have now has not come easy. The life I have now was never guaranteed. It took a lot of pain to get here, but I treasure my life in the present. Even if sometimes, when I look in the mirror, I still wish I could see my former face.

Samuel Moore-Sobel is a speaker, columnist and author of “Can You See My Scars?” He is a fellow burn survivor, and an amazing writer at the impressive age of just 26 years old. His book is available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Mascot Books. For more, follow him on Twitter and Instagram or visit www.samuelmoore-sobel.com

Dr. Lise Deguire’s memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader or your local indie bookstore. Flashback Girl is now available in paperback, eBook and audio book format.

March 12, 2021

5 Things to Say to a Scarred Person (and 1 Thing Not to Say)

A year ago, I sat eating lunch with my new friend, Betsy. We met when our kids performed in high school theater together. We both volunteered, selling cookies and water during intermissions in the sweaty clammy auditorium. Over time, Betsy's warm wit charmed me and I wanted to know her better.

When meeting someone new, I rarely bring up my extensive burn scars right away. The fire I endured as a four-year-old, my years of surgery, these traumas don’t belong in introductory conversations. But I am well-aware that new friends have questions. I know that everyone has questions. I just don’t feel like going there unless I am truly drawn to a person.

But Betsy had charmed me. So, I brought up the fire, my own way of opening the door to whatever questions she might have. Betsy smiled at me, brown eyes warm and bright, and exclaimed, “But I don’t even see your scars!”

I have heard this statement countless times. (For more on this topic, see this relevant article) I never know how to respond. What does this even mean?

You are blind. You would have to be visually impaired not to see my scars. I am facially scarred, as well as on my neck, chest, both arms and both legs. In the winter, completely bundled up and wearing a COVID mask, you could, theoretically, not see my scars. Other than that, let’s be clear, you see them.

You used to see them, but now you don’t. I think this is what this statement means. So, let’s follow that rabbit hole. Why do you no longer see my scars? Is it because I have become so lovable that my sparkling personality overcomes my defects? I understand this is meant to be nice. On the other hand, how would you feel if I declared, “I don’t even see that you are short!” Or “I don’t even see that you are obese!” Would that feel good?

The statement focuses on my scars as defects, which, now that you like me, have disappeared in the light of affection. With love, my scars cannot be seen! But let’s unpack that from my perspective. I am scarred on two-third of my body. I have spent over 50 years in this body. I wouldn’t say that I like my scars, but I also wouldn’t say that I hate them. My scars are a part of me. They signify my odyssey through terror, abandonment, surgeries, hospitalizations, bullying and rejection. My scarred skin is tough and so am I. I would prefer not to have scars, and yet I would miss them if they were gone. My scars are extraordinary and mark me as an extraordinary person.

When a person says, “But I don’t even see your scars!” I have no idea how to respond. What am I supposed to say? “That’s nice?” Or “Thank you?” I don’t feel complimented. I feel unseen and diminished.

I believe that most people claim they don’t see my scars because they have no idea what else to say. And you know what, I get that. We are not educated on how to handle social difference, and most of us are terrified to say the wrong thing. We don’t want to offend. I understand.

Let me offer some suggestions. As a general principle, I don’t need to know how you reacted to my scars. That is your journey. (Just like you wouldn't wish to know how I reacted to your being chubby, short or balding). But I would love to feel close and safe with you. So, if I bring up my burns to you, what could you say that would feel good to me?

“I would like to learn about your injury, if you want to tell me”: This statement lets me know that you are interested in my journey, and that you want to know about my pain. It also gives me permission to decline the conversation if I’m not up to it. Telling you about my injury is necessary for us to get closer, but it will also be exhausting for both of us.

“I love you as you are”. This is how I wish to be loved, and isn’t this true for all of us? I don’t want to be loved with blinders on, eyes squeezed so tight that you can’t see what I have been through. I want to be loved for the person I am, which includes, although is not limited to, my trauma and struggles.

Or, just Say Nothing: One of the issues about scarring is that everyone can see it (despite what you declare to the contrary) so everyone feels some need to address it. I get this, but it is a drag. We all have burdens and hardships that we carry – most are not visible. The difference is that you can instantly see my burden, but I can't see yours. Imagine, though, that everyone could immediately see that you drink too much. Imagine that every new person felt compelled to offer commentary. Strangers at a party. . . People in the grocery story. . . Every single person with whom you wanted to be friends. They say,

“I see that you drink too much. How did that happen?”

“It must be so hard that you drink too much.”

“How long ago did you start drinking too much? What has it been like? Have you had treatment? How many treatments did you have? Will you have more? Are they painful?”

Or. . . “I don’t even see that you drink too much!”

My point is that sometimes less is more. You can convey that you care about your new friend without offering commentary on how they look or what they have been through. Just as you might not welcome my commentary on anything about your body, I don’t generally welcome your commentary on my scars.

What I long for most of all is love and friendship. In this way, I am just like you. So what can you say?

“Are you OK?”

“Do you need anything?”

“ I am here for you.”

Or, best of all, “I love you. I’m glad to be your friend.” That is what you can say.

The author's memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

February 26, 2021

For Me, There Is No Rest

by Kevin Barhydt, guest blogger

I am honored to host Kevin Barhydt, as the first guest writer for this blog. You can learn more about Kevin, and his book, Dear Stephen Michael's Mother at the end of this post.

"I know we can't slow down

We can't hold back, though you know, we wish we could

Oh no, there ain't no rest for the wicked

Until we close our eyes for good"

- Ain't No Rest for the Wicked

by Cage The Elephant

For an adoptee like me seeking a place in this world to call my own, I never rest, can't slow down, won't ever hold back for one minute. I must be resilient, and that resilience is a hard won attribute, kept alive only through a daily fight to the finish, and a lifetime struggle seemingly beyond my own natural born endurance.

As a survivor of child sexual abuse at the tender age of nine I'm less likely to view resiliency as a benefitial strength, but more as a burden that allows me to carry those deviate memories and yet rise anew each day.

My hope as a recovering addict and alcoholic is to recapture and restore the healthy qualities of my infancy, before my God given instinctual resiliency was deformed into a mechanism designed to allow me to barely function as a human so as to continue the daily chore of ingesting substances in the slow act of chemical suicide.

As I openly articulate here for you my struggles, burdens, hopes and fears, I also need you to know that I do so through a grief and sadness that has never fully broken me and yet never fully leaves me. You see, I already wrote this piece once, and sent it off cheerfully, only to find a response in my inbox from Lise "I think you are at a good first round with this piece. May I make some requests/suggestions for it, as I think it could be even better…"

That simple reflection, written in kindness and generosity, would have nearly broken me in two. Even after thirty-five years of sobriety, I'm still not better. After the monumental healing as a survivor of child sexual abuse, I'm still not whole. As an adoptee with an entire world full of love and family and friends, I'm still unwanted. Even with all the tenderness and goodness and kindness that I have learned to direct from and towards myself, it simply isn't enough. Or, maybe, just maybe...

…

"I have been loved, Edward told the stars.

So?, said the stars. What difference does that make when you are all alone now?"

In Kate DiCamillo's timeless story, "The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane," I feel a kinship of loss and grief, as well as of hope, reunion and redemption. As an adoptee, survivor of child sexual abuse, and a recovering addict and alcoholic, I also find in this story a parable of the power of community.

Resiliency for me as an adoptee is a matter of life or death. The story of my worth in the world began with the truths I was told. That my mother loved me so much that she gave me away, and that my adoptive parents had so much love to give that they took me as their own. If the person who created me loved me so much she relinquished me, it was simple to surmise it was only a matter of time before my adoptive parents would do the same. My worth was transactional.

Child sexual abuse survivors find a similar value system placed on their bodies. We are groomed and told we are special, only to be led into a darkness beyond the comprehension of most non-survivors. We are a piece of meat, lost to our own sense of self, and left to find solace and value in a place where there is only an absence of worth.

Addiction first becomes an oasis, then refuge, and finally the one place where the darkness on the outside equals our darkness within.

I wasn't meant to be this way. I was designed to be secure in who and what I am, strong and confident. I was made to be resilient. I was created with the capacity for bonding with others, but entered the world an unwilling orphan with a primal wound, torn away from my biological origins. As a child I had a tremendous capacity for empathy and joy, and an inner sense of self worth, only to have the act of a pedophile destroy my innocence under the guise of an adult's kindness and secrets. My adoptive family were sound of mind and body, but my genetic ancestry contained a multitude of addiction and mental health illnesses.

As all of the aspects of Personal Resilience were torn from my hands, the loss of control over my environment mutated my relationships and natural creative instincts into self-centered self loathing, and an understanding that my own existence was both helpless and hopeless. Then, when I least expected, a shift happened. For me, it was two words: maybe, and might. A friend said "maybe you need help" and another said "you just might be an addict and alcoholic."

Many had tried to help before. Every priest, parent, social worker, police officer, even the US Navy had told me that I needed help. This was different. Maybe. Might. This was optional. In the depths of despair I saw a flickering hope. Still in the grip of suicidal thoughts, I reached out for help, one baby step at a time. Then, slowly, time passed and my community of support grew. My 12-step friends, and sponsor. My therapist and doctors. Teachers and students, professors and authors, actors and poets. Finally, my family. My wife, mother, father, daughters and sons.

The time was necessary. My neurological healing could not be rushed. My mental health and intellectual acuity improved greatly, sometimes at such a rapid pace that I found myself racing to keep up emotionally. With healing in progress the restoration of resilience became possible. All the time in the world would not have been enough to restore my innate resiliency without the ever expanding foundation of a community to support me. By accepting the help of others I became more capable of healing and strengthening all that had been broken. When I accepted my circumstances, past and present, I found that powerlessness could be transformed to hopefulness. Through my dependency on community I developed an inner state of personal autonomy, and a genuine sense of purpose.

With those in my life who understand the tears of my past, as well as the mending that will always be my present, perhaps my resiliency will grow. Maybe I'll know the new prospects of a life manifest through love, compassion and courage. Then, perhaps I might enjoy the possibility that my friend Lise Deguire holds out as her own hope, for her and our community.

"Maybe now I can rest."

Kevin Barhydt is an author and YouTube creator. You can connect with him on his website: https://www.kevinbarhydt.com. Kevin's memoir Dear Stephen Michael's Mother, is now available on Amazon.

February 12, 2021

It's the Most Loneliest Day of the Year

Note: I wrote this piece two years ago, and reprint it every February. Sending love to all those who feel alone; I have been there too.

I used to dread Valentine’s Day, the holiday of the loved and desired. My friend Hannah would dress confidently in her fuzzy red sweater, brown curls bobbing around her oval face and perky figure. She smiled with anticipation. There would be a pink card and teddy bear from her boyfriend. She would get a cookie from her co-worker who eyed her longingly, and a late-night breathy phone call from her ex. Hannah’s only concern was what to wear for the day.

As a burn survivor, men were not falling over themselves to declare their devotion to me. I might have worn the cutest red sweater, and the tightest of jeans, but Valentine’s Day crushed me. Whatever men I admired usually were oblivious to my affections. I never had a boyfriend. My best hope would be that my parents might remember to send me some candy. That happened, once.

Valentine’s Day was the loneliest, most depressing day of the year. Now, decades later, I am happily married, and the day is just a sweet holiday. But I remember all those years of feeling unloved and unwanted. And it wasn’t just me, feeling so alienated on a day that’s supposed to be about love. I don’t think February 14th is a picnic for the recently divorced, the widowed, the unhappily coupled, for closeted gay people; I could go on and on.

Suppose this is you. Are you single? Are you always single, painfully so? Are you the one without a date to your best friend’s wedding, and no valentine in sight? I hear you, darling. I see you. I have been there. I have cried my eyes out on Valentines Day, many times. But please hear me now.

You don’t have to be perfect to find love. You don’t have to be a certain size or shape. You don’t have to be physically beautiful. You don’t have to be able-bodied or unscarred. You don’t have to be a college graduate or have a great job. Love can come for all of us, at any time. Try to be patient and hopeful. Believe me, if a 65% severely burned woman can find love, you can too. It only takes one person to come along. It only takes one person to see you. Love may not be here yet, but that doesn’t mean love won’t come.

In the meantime, work on caring for yourself. You are the only person that will be with you, by your side, for every day of your life, so be a kind companion. Fill your mind with caring thoughts. Spend time with loving friends and family. Smile in the mirror and hold your head high. You are the only you, and you are a marvel of the universe.

And Happy Valentine’s Day.

#ValentinesDay #resilience #SelfCare

January 29, 2021

"In a World of Pure Imagination"

(Author's note: The following is a chapter that originally appeared near the end of Flashback Girl. I was advised to edit it out, for various reasons (interrupted the flow, repeated some themes, went back in time too much. But, as many authors can relate, just because the chapter had to be edited out doesn't mean it wasn't worth sharing. So, I am happy to share this chapter here.)

One way to survive an unsurvivable childhood is by not being in it. As a child, I spent years pretending to be someone else, who lived somewhere else. In my games, I was happy, strong, safe, and loved. Any dangers emerged from my own imagination and faded away by the end of the game. I was an orphan, the eldest of six, rescuing my siblings from starvation. I was a World War II spy. I led a wagon train across the Dakota plains. My escapes into fantasy didn’t fully end until I married, finally establishing a safe home and family for myself.

Sometimes I had playmates. I played Batman with Marc, I played I Dream of Jeannie with Michael. Many times, I imagined alone. I sang along to my show records, imagining myself to be Nellie Forbush or Peter Pan. I played alone, sending my fashionably-dressed Barbies off on dates with Marc’s old G.I. Joes. But I met my true imagination partner when I met Melissa.

Melissa was the daughter of my dad’s old friend, Patty. Like me, Patty had a difficult childhood, full of neglect and fear. She became a gifted ballerina. My dad met her at his college job, playing piano for her ballet classes. They kept in touch over the years, my mom and dad, Patty, and her husband, Talis.

I remember the first time Melissa came to Glen Ridge. She was so pretty, with straight blonde hair, wide blue eyes and an angelic face. She was an athlete, unlike myself, who could never catch a ball, my eyes squeezed shut with anxiety. So, Melissa was lovely and I was ugly, and she was athletic and I was a dork. None of that mattered though, because Melissa knew how to play. She had the same all-encompassing imagination that I had. We clicked.

Melissa lived in Bayside in Queens, New York. I lived in Glen Ridge, New Jersey. Soon after meeting, we became fervently devoted to seeing each other as much as possible, which did not make things easy. This problem was quickly solved by our parents declaring that we were old enough to take public transportation. Thus, I began traveling to New York City by myself by the age of nine.

The first time, my mother took me. We walked to the bus stop and waited on Bloomfield Avenue for the #33 to come. In Port Authority, we took the subway downtown to Penn Station. She taught me how to buy a ticket for the Long Island Railroad, and how to find the correct train platform. Then we rode the train, and she showed me the stop to get off for Melissa’s house.

We did this trip together once. The next time, my mother wrote out all the travel steps on a little piece of paper and sent me off. I clutched that paper fearfully in my hands, anxiously triple checking every step I took along the way. I tucked the paper deep in my pocket, terrified that I could lose it. Still, I made it, all the way to the heaven that was Melissa’s house.

Melissa lived in an elegant four-bedroom house with sunny windows and beautiful artwork. There was always music playing. Sometimes it was Patty, playing one of her many records. Sometimes it was Melissa’s brother Mark, an excellent pianist, practicing for admission into music conservatories. Talis, Melissa’s dad, was often painting. He was an artist, and he had a home studio, where he spent most of his time. Unlike my mother, Patty was always home, taking care of everyone. I adored her.

Patty made a place for me in her house. I came at least once a month, often more. You would think she might have gotten tired of taking care of me, cooking for me, mothering me. If she did get tired of me, she never showed it. Patty would smile so warmly whenever I arrived. Sometimes after dinner, we would linger in the kitchen, the two of us chatting away. I always felt that she loved me so much.

When I was with Melissa, I could be in another world. Sometimes we pretended we were dogs. We had an entire cast of dog characters, with various relationships and issues. She was Rontu, named after the dog in the The Island of Blue Dolphins, and I was Rusty. The Rontu and Rusty game came early, when we were about nine and ten. I’m pretty sure that game was her idea because I was not into dogs at the time. Still, Melissa made everything fun.

Sometimes we pretended we were horses. In our play, we created a well-established horse world, loosely based on the Black Stallion books by Walter Farley. There was Black (Melissa) and Flame (me). We galloped around my front lawn, whinnying for our horse friends, escaping various perils, making our way to safe meadows. My large yard in Glen Ridge became a clearly defined horse world, in which various zones had their own names, with different horses living in each area.

Our imaginary feats rose to a grand crescendo when we forsook horses and fell in love with The Beatles. This happened during middle school and lasted about three years. It was not unusual for middle school girls to be obsessed with bands. However, this being Melissa and me, we went far beyond that. In our minds, we became the actual Beatles.

I really don’t know how it started, but I was Paul McCartney and she was John Lennon. This was the opposite of our personal preferences, because I was a John fan and she was a Paul girl. It was more fun to pretend to interact with the Beatle one adored, so that’s how we did it. Sometimes we were John and Paul, writing songs together. Sometimes the game was about Paul and Linda McCartney. Sometimes it was Paul and Jane Asher. Sometimes it was John and Cynthia Lennon. Sometimes it was John and Yoko Ono.

Almost all the time, we were pretending in this elaborate fantasy world. We listened to the Beatles constantly, and knew every song. We would sing the harmonies together, or rather, we valiantly tried. I could always sing, and I had a good ear, so it was easy for me to pick out all the vocal parts. Music was not Melissa’s gift. I never understood why she couldn’t just sing the harmonies that John sang. It seemed so easy to me. (Perhaps this is how she felt about me, every time I failed to catch a ball.)

Things reached an intense pitch in seventh grade. This was the dreadful year when my parents separated, my cat ran away, Marc dropped out of MIT, my Pepere got cancer, and I was being tormented in school. My primitive way to survive this time was to simply not be there. Every possible minute, I pretended I was in the Beatles world. I paid enough attention to get decent grades. When I had to interact with another person, I could. But when I was left alone (which was most of the time, as a neglected, bullied kid), I immediately pretended I was a Beatle again. I wrote Melissa very long letters, ten double-sided pages at a time. I scribbled the letters in school, so I didn’t have to think about where I actually was. I wrote to her constantly. The envelope would be addressed to Melissa, but the letter would be written to John, or Jane or Linda.

Dimly, I knew that perhaps this Beatles thing was a bit much. On some level, I understood that it was not healthy to live every day in a fantasy. However, pretending to be a Beatle seemed preferable to complete despondency. Although I was lost in fantasy most of the time, I was not psychotic; I knew it was pretend. I just vastly preferred pretend to real.

In eighth grade, my mother and I moved to Oyster Bay, Long Island. One of the good things about moving was that it made it easier to see Melissa, and we did see each other even more. However, when I moved to Oyster Bay, I made actual friends for the first time in years. I began to want to see my new friends, and to live in the world as it was truly happening.

I started to pull away from Melissa a bit. I didn’t want to play Beatles anymore. I am entirely sure that I didn’t communicate this to her in a clear, helpful or kind way. I think I just started to be more distant and less interested in our mutual world. I could feel her anxiety, which was a new dynamic. For years, she was the top dog (Rontu, for example). Now it was me.

My brother Marc jumped off the Green Building at MIT right when I started 9th grade. Along with my shock and grief, I made an immediate self-assessment. I was 14. In a flash, it came to me, as clear as anything ever has… if I retreated into fantasy now, after Marc's death, I would not remain sane. I had survived all my traumas by pretending to be someone else. But I knew that I had face Marc’s death, or I would go crazy.

It is hazy to me, but somehow I told Melissa that I couldn’t be close with her anymore. I don’t know how I said it. I am confident that I didn’t say it in the best way. I was 14 and completely traumatized. I know I didn’t convey that our intense escapist relationship was now dangerous to my mental stability.

This was my first time terribly hurting someone, but not my last. In my life, I have detached three times from an intense relationship in order to be emotionally stable. Each of these ruptures was gut-wrenching, leaving me a lifetime of remorse and second-guessing. My ability to detach with modulated kindness has improved over time, but the rupture is still awful.

The feeling reminds me of the end of the movie Titanic, when Rose has to let Jack go. The two of them can’t fit on the floating door in the Atlantic, and she will only live if she lets him go. Jack has no chance to survive and he pleasantly accepts his fate. That is nice and touching in the movies, but in actual life the feeling is very different. The Jacks in my life have not been so sanguine.

My fantasy life with Melissa was over, and I did my best to stay sane. I went to therapy and I didn’t kill myself. Over time, with help, I healed. I no longer needed to escape reality, just to get by.

After our rupture, I lost touch with Melissa for many years. I kept in contact with Patty, who had been like a mother to me. Melissa and I were only distantly connected. I knew she had married, and had a daughter, and that’s about it. I tried to Facebook friend her, but she never responded. I didn't blame her. I understood why she might not want to be my friend.

A few years ago, Patty died. I wrote a long letter to Melissa and Mark, expressing my condolences and sharing my appreciations of Patty and everything she did for me. I didn’t hear back from them. Again, I didn't blame her. I understood why.

Awhile after my mother went to Switzerland and took her life, I got an email from Melissa, saying she was very sorry to hear about my mother, and asking if I wanted to talk. I was stunned to hear from her. Nervously, I called the number she had written.

“Hello?” she answered, in a voice that I would have known anywhere. We fell into conversation effortlessly, as if 40 years hadn’t gone by. We talked about my parents’ deaths. We talked about her parents’ deaths. We caught up on our marriages and our kids and our work. We talked for an hour.

At some point, I took a deep breath. “I am sorry, Melissa. I am so sorry for breaking off our friendship the way I did.”

“Oh, that was so long ago,” she said breezily.

“I know, but I think about it a lot, and I am very sorry.” There was a pause. We were quiet together.

“I was really devastated.”

“I know. I’m so sorry.” I went on to explain that I couldn’t stay in our friendship because of the level of fantasy, and my fear for my sanity.

“We were just pretending. Kids pretend.”

“Yes, but I was pretending ALL THE TIME. I was pretending at school, at home, and everywhere I went, even when I wasn’t with you. It was all the time. I really thought I might go crazy.”

“Oh!” she said, with a surprised laugh. “Wow!”

“That’s why. But I didn’t handle it well and I’m really sorry.”

Now, we are friends again. We remind each other of our exploits from many years ago. We sing old camp songs to each other. It is sweet how well our adult brains click together, just like we used to when we were little. Now, instead of horse game ideas, we talk about dogs (real dogs!), daughters, work, and family. I never would have guessed it, but here we are.

Rontu and Rusty forever!

Lesson: Fantasy and pretending is a way to get through trauma, imagining a better life for yourself. Keep your feet on the ground though.

The author's memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

January 15, 2021

A Tale of Two Siblings

(Note: This piece was originally published in Tiny Buddha, under the title "Beating the Odds: Why I Survived and My Brother Did Not.")

My brother, Marc-Emile, sparkled. At sixteen years old, he could expound on physics or Plato, calculus, or car mechanics, Stravinsky or Steppenwolf. At seventeen, he began reading the Great Books series, starting with Homer and Aeschylus and moving forward through the Greeks. I don’t know how many of those Great Books he read. He didn’t have that long.

Marc had everything going for him. He was kind, ethical, and handsome. He graduated high school a year early, at the top of his class, with virtually perfect SATs. He started at MIT as a physics major. He ended at MIT too, one year later. At the age of nineteen, he flung himself to his death from the tallest campus building.

Then there was me, Marc’s little sister. Everyone knew me too, but not because I was brilliant. I was exceptional in a less appealing way, having been severely burned in a fire when I was four years old. I barely survived this injury, which left me with no lower lip, no chin, no neck and my upper arms fused to my torso. Bright purple raised scars traveled the length of my small body.

I spent month after month in the hospital alone, undergoing one terrifying reconstructive surgery after the next. When I was home, I was bullied and taunted, kids running past me, screaming “Yuck!” as they fled, laughing. The children’s hospital ward was my playground. Wheelchair races were my soccer. I couldn’t take ballet because I couldn’t lift my arms above my head.

So why is it that I am now living a contented, fulfilling life, happily married and surrounded by friends? And why is it that my exceptional, gifted brother took his own life forty years ago? No one would have bet on this outcome.

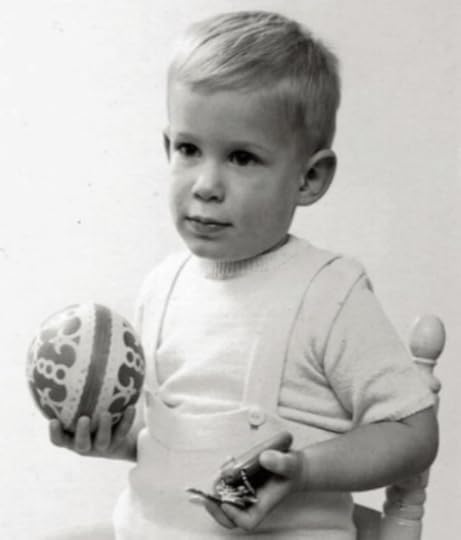

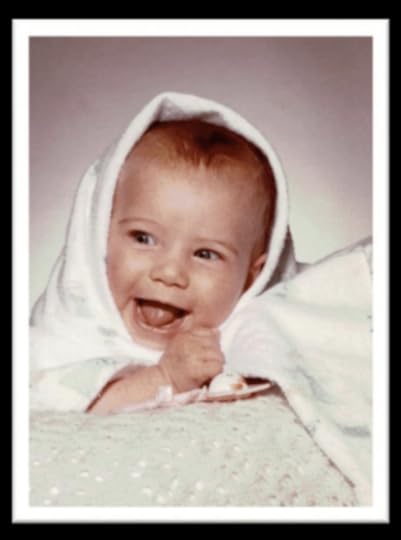

Perhaps a clue lay in our baby photos. As toddlers, each of us had been brought to a professional photographer’s studio. In his photos, my brother sits cooperatively on a wooden stool, holding a ball with stars on it. He looks at the camera with pensive eyes, half-smiling. In another photo, he gamely holds a toy train. Again, he peers into the camera, observing and reticent.

The page turns in the photo album and there I am. I laugh, mouth stretched as wide as possible. I point, tiny eyebrows comically raised. I hold my head coquettishly. I am probably nine months old and clearly having the time of my life. I don’t even need a toy. I’m a party all by myself.

My basic temperament was different from Marc’s. I was friendly; he was introverted. I was optimistic; he tended toward depression. I was gleeful; he was sad. From the start, we displayed these differences, differences, which turn out to be vital factors in our survival.

I have spent my lifetime trying to figure out why I am still here when my brother is not. It feels wrong, even four decades later. I feel his absence as an ache in my chest, a slight stabbing on the left side, like a slender silver knife slipping into my heart. His absence has been present within me, every day of my life.

A day I have grown to loathe is National Siblings Day, a reoccurring nightmare of a day, which happens every April 10. My friends post loving photos of themselves, arms around their brother or sister. Sometimes they share old photos taken decades ago and pose cleverly in new photos to recreate the original picture. They stand, embracing each other in an identical pose, but now with gray hair and glasses. They smile, grinning at the years that have passed, sharing the joke together.

I don’t know how National Siblings Day started, or whose bright idea it was. I never used to have to endure this day. My only comfort, and this is cold comfort indeed, is the comradery of my friend’s daughter, who lost her only sibling four years ago. Every year, for the past four years, I have texted dear Laura on April 10th.

“Happy F-g National Siblings Day. I love you.”

Within seconds, Laura responds. “I know. It’s awful. I love you too.”

I am here, Marc is not. I am resilient, despite the odds against me. He was not resilient, despite the odds in his favor. It turns out that being naturally cheerful might be more important than acing the SATs.

Perhaps in this time of COVID-19 and other assorted disasters, the capacity to be cheerful is the most crucial gift of all.

I am upbeat and optimistic, despite being burned, abandoned, neglected, bullied, and despite losing my favorite person in the world. I don’t necessarily mean to be cheerful; it just happens. I’m like the red and white plastic bobber on the end of a fishing line. I go under and then just pop back up again, for no real reason other than that’s just what I do. It’s my temperament; I don’t choose it.

Marc didn’t choose his temperament either; none of us do. Our genes are what they are. But luckily, genetics are not the only factor in resilience. Life experience matters too, and so does social support.

Optimism can be encouraged. Gratitude can be worked on. We can teach people the skills to cope, in our homes, our schools, or our psychotherapy offices.

We can impart the importance of physical, mental, and emotional self-care so they develop a strong foundation of well-being. We can give them tools to handle life’s challenges—like reframing struggles as opportunities, focusing on things they can control, finding strength in all they’ve overcome, and letting people in. And we can teach them to recognize stress before it escalates so they can calm and sooth themselves.

Resilience is like intelligence: some people are born naturally smarter, but everyone can learn. Some people are born more resilient, but everyone can be helped.

We need to keep our collective eyes out for those who are sad, who seem hopeless, who don’t smile for the camera. We really need to keep our eyes peeled now, during this time of quarantine and social isolation, because emotional distress is on the rise.

Science tells us resilience can be improved. However, offering help will be more complicated, time-consuming, and expensive than simply exhorting, “Be more resilient!” Demanding resilience does not make it happen. Some people need to be taught how.

Let’s not pretend we all begin at the same starting line. And, speaking from a lifetime of missing my brother… let’s not leave anyone behind.

The author's memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.