Lise Deguire's Blog, page 4

August 10, 2022

A Dose of Compassion, Doctor's Orders

I have been a patient and a doctor, on both sides of the bed. I have sat with injured people, processing their trauma. I have also been the wounded person, working with a therapist on my trauma. This duality is both my burden and my strength.

I have been bored and exhausted, slogging through an 8:00 PM appointment, driving home afterwards in the dark winter night. I have experienced exasperation with clients who laze through sessions, neglecting the homework I carefully assigned. I have bitten my tongue, or regrettably, sometimes not bitten my tongue, under the weight of too much work.

On the other side, I have had nurses who forgot about me while I lay in excruciating pain. I have missed meals because no aide remembered to bring me my dinner tray. Anesthesiologists have put me to sleep against my will, forcing a mask over my face while I writhed. Nurses have ripped off my bandages while I begged them to stop.

I know both sides.

I think compassion is our most vital healing tool, but the one we least prioritize. I’m impressed my surgeon knows all the latest techniques, having inventing some of them herself. I’m grateful to heal without infection, my scars gradually laying flatter and smoother. But you know what keeps me returning for surgeries? My surgeon makes me feel safe and valued. The whole burn team surrounds me with love. That is how I can continue my burn care, even though the procedures scare and hurt me, every single time.

As a patient, I thirst for connection. My gut instantly recognizes the staff who care, who know my name, who want me to feel safe. Some staff look me straight in the eye and see another human being - not a “patient”. They smile freely and converse, instead of gazing with detachment at the computer screen.

To be sure, I know how to prime that pump. Years of hospitalization as a child, all alone, taught me how to engage staff. I had to figure it out because I had no parents to help me. I learned to make eye contact, to call nurses by name, and to ask how they were doing. I knew how to make myself stand out, so I was not just the patient in “Bed 4.” I became Lise Deguire, valiant burn survivor, the one who is charming, funny, and thoughtful.

I work hard to engage my care team, and I am good at it. But, let me tell you, it doesn’t always work. Last year, I was briefly hospitalized for what turned out to be a kidney stone. The E.R. nurse could have cared less. She didn’t smile or even introduce herself. She did not show the slightest concern for my pain.

I smiled and asked her name. I chatted about the evening. Nothing... I got nowhere. Finally, I said, “Has COVID been tough for you?”

She snorted. “I haven’t had a vacation day in a year.”

“A YEAR?!”

“Yes, a year.” Even after this brief bonding moment, I could not connect with this nurse emotionally. But at least I understood why. Her compassion tank had run bone dry.

As an adult, I refuse to see doctors who don’t show care for me. Every doctor I see, from my primary, to my G.I., from my dentist, to my surgeon, every one of them is kindly engaged. The technical excellence of the doctor is not my only priority, foremost they have to care.

Compassion isn’t measured by hospital surveys or touted as outcome measures. You don’t read about the “most compassionate surgeon” in U.S. News and World Report. But ultimately, people seek compassion as much as any other outcome. Sometimes in my practice, physicians and psychologists seek me out for their personal psychotherapy. It used to surprise me, as there are plenty of psychologists who are more accomplished, psychologists who publish and develop new techniques. I am a solid clinician but not nationally known.

You know what I am though? I am reliably compassionate. And that is what people crave when they hurt.

There are, sadly, plenty of cases where there isn’t much to be done besides compassionate listening. A client loses her only daughter. Another client has three months to live. Another client dives wrong and is rendered permanently quadriplegic. Yes, we can work on dysfunctional thought patterns and understand their trauma history, and these techniques will help. But I think what really heals people in dire circumstances is compassionate listening, listening with an open heart. I suspect my own history of medical trauma helps me stay extra-caring. I know compassion is crucial when people are scared out of their wits.

Compassion is at least half of what heals us, and maybe more.

Suppose we prioritized compassion in health care? Suppose there was a procedure code for 15 minutes of compassion. Imagine a doctor or nurse pulling up a chair by your bedside, talking about life, asking you how you are feeling, maybe holding your hand. There are nurses who do this now, truly they are, but they grasp for the stolen moment, between documentation and bandage changes.

Recently, I had the honor of addressing the American Burn Association, where I spontaneously coined the phrase “micro-moments of kindness.” I wanted these busy, over-worked providers to know that even the smallest of interactions can be healing. Yes, 15 minutes of compassion would be better. But even one minute of kind, gentle listening profoundly impact patients.

Sadly, compassion has become the occasional bonus gift, as opposed to the most fundamental healing element of all.

Suppose we offered professional recognition for compassion? Suppose we gave regular training on the importance of compassion? Suppose we also treated health care professionals with compassion, so that their tanks didn’t run dry, like that E.R. nurse last year.

A hospital administrator once told me that delivering compassion was “my job,” as the staff psychologist. That same administrator later outsourced this job, eventually eliminating it altogether. Compassion doesn’t make money, I guess. (Or does it? Because like I said, I only return to doctors who are kind.)

We assume health care professionals will be , despite being overworked, traumatized, and given no priority. Even in my profession, psychology, compassion is assumed to exist, without specific training. We really don't talk about it much.

From the patient side of the bed, the people I want are:

- Anthony, the aide with the kindest brown eyes, who smiles broadly when he greets me at the burn unit door.

- Michelle, the nurse, whose forehead frowns with silent sympathy when I cry in pain, and who works diligently to help me heal.

- Jill, the nurse-anesthetist, who moves heaven and earth so that the anesthesia process doesn’t re-traumatize me.

I doubt that any of these people receive recognition for their special compassion, and I bet they aren’t paid extra for it either. But that’s who I want when I am vulnerable and scared. And I bet you do too.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

July 28, 2022

What the Shaman Said

“The ancients knew something, which we seem to have forgotten.” Albert Einstein

Life takes us interesting directions, and mine recently involved consulting a shaman. Do not roll your eyes. I have a scientific education from two universities. I earned a doctorate in psychology and was raised by atheists. I am open-minded, but no pushover.

My parents taught me to cherish music, intellect, and literature, but to scorn religion. My mother found her Lutheran upbringing oppressive. My father, a closeted gay person, could not breathe a word about his sexuality to his working class, devoutly Catholic parents.

When they married, my parents cast off their religious traditions and went full-on hedonist. I do not exaggerate. They placed no limits on themselves in pursuit of bodily pleasures, leaving a wake of booze, drugs, and sexual escapades trailing behind. Their mindset was bacchanalian, their pursuit of pleasure at just about any price. In my father’s case, this mindset ultimately cost him his life.

I struggled to find my way, spiritually. I guess I never fit in with my family because I believe in a whole lot more than… nothing. Life’s pleasures are delicious, but never felt like the reason I was here. The universe is vastly bigger than we can perceive. Magic happens, little miracles which defy rational explanation. This very blog, the fact that you are even reading my words… I am not a trained writer. I have no idea how I wrote such an awesome book. Seriously. Creativity comes through me, it is not of me. Rationality has never felt like the whole story. So, when my dear friend suggested I consult his shaman for guidance, curiosity pulled me in.

I am not going to discuss the whole shaman session, which was deeply personal and, honestly, pretty weird. The general gist involved a few main points: spirits, my life path, and my need for protection.

“There is a spirit around you. She needs forgiveness,” the shaman began.

“Oh. That would be my mother.”

“She has passed?”

“Yes.”

“She needs your forgiveness, which is why she is all around. Have you forgiven her?”

“Not exactly. I mean, I understand her. But she did enormous damage to me and my brother, life-threating damage. She never acknowledged her mistakes.”

“Beyond the veil, we are shown our life and our choices. She understands now what she did. She needs your forgiveness to be released from her karma.

“My mother never said she was sorry or sought forgiveness. To some degree, it is her fault that my brother died. It is awfully hard to forgive someone who was never even sorry.”

The shaman’s voice deepened, and he gravely replied, “Well, she’s sorry now.” He paused and took a breath. “If you do not forgive her and release her, she may reincarnate back into your bloodline, perhaps as your grandchild.”

Reincarnate into my blood line? As my grandchild! “OK then, what do I do?”

I was given assignments to establish forgiveness for my mother and my father. I had not thought about my father’s impact on me for a while, beyond missing him. He died 25 years ago, and we were on tender terms at the time. So, it was happen-stance, or not at all happen-stance, when my husband unearthed a dusty box of my dad’s writings from our attic, right after I spoke with the shaman.

My dad wrote these letters to himself over the course of 20 years. They detailed his true thoughts and feelings about my mother, my brother and me, and (mostly) himself. Suffice it to say, all the dark sides of my father re-emerged in stark relief: his rage, his self-focus, his lack of accountability. In his letters, I flipped back and forth from being the best daughter ever to being a “bitch just like her mother”.

My heart broke. As a child, I labored valiantly to be loved, suppressing my fully accurate perceptions about being neglected. I had a choice. I could be cheerful and charming, or I could speak my truth. I could whitewash my parents’ neglect and be cared for, or I could be authentic and be abandoned. It was one or the other.

The shaman assigned rituals to release my parents from their karmic burdens. The rituals involved writing and burning letters and releasing the ashes into a river. I diligently completed these rituals, despite my fear of setting fires (burn survivor, remember?) Multiple times during these tasks, my mother’s letter refused to go. Her letter would not catch fire (irony of all ironies!). When I brought the ashes to the river, my dad’s letter quickly swept downstream. However, my mom’s letter would not drift away. I had to coax the ashes with my hand, moving the water along to finally claim them.

Strange, huh?

The second issue, according to the Shaman, was that I need to open up my “heart chakra.” He repeated this several times, and I finally asked, “So I don’t get this part. Why do I need to open up my heart chakra? I am quite a loving person.”

“Yes, but our ancestors want us to love everyone deeply. Everyone.”

“Everyone! That’s a high bar.”

“That is what they want from us.”

As much as I need to expand my heart, the shaman said that I also needed help. He said that I am "walking in the light now,” but that dark forces also surround me. The more one walks in the light, the harder dark forces work to undermine us. So, he said I needed “extra protection.”

My 59-year-old heart beats strong and true, but it has always needed protection, both literally and metaphorically. Because of the extensive burns on my chest, the fat layers and some musculature around my heart were permanently eviscerated. When I place a hand on my chest, there is only burned skin and bony rib cage surrounding my heart. There are no soft layers of insulation. My heart works perilously close to the surface.

Also, I am so open. I say what I feel, and I feel deeply. Many readers of Flashback Girl remark how vulnerable and honest the book is. The book is that way because I am that way. Although I don’t remember, apparently I have always been. I hear from people I knew from elementary school who vividly remember me as being kind, authentic and joyful, well before I had any consciousness of these traits.

There is good and bad in being this open. The good is whatever is accomplished by being true, kind, and real. Truth, kindness, and authenticity heal people.

The bad is that negativity cuts me deep. Because my heart is so open, I feel crushed by unkind words, by criticism and God knows, by cruelty. (The exception being when I work as a psychologist, because then I operate in a whole different professional zone. My professional boundaries are solid, protective, and firm.)

Some people don’t like people who are trying to do good. You know, those dark forces. They are out there.

So, when the shaman suggested that I needed more protection for my heart, I was down with that idea. There were quite a few more rituals for this. I chanted, lit candles, burned sage. I felt a little silly but also curious. I mean, who knows, right? And really, what did I have to lose?

A few days later, I had a conversation in which I felt deeply criticized, the kind of talk that could send me into a funk for days. I started down that rabbit hole, when suddenly I felt an energetic force-field around me. A curtain quickly folded around my heart, protecting me from pain. “Whoosh,” went the curtain, cloaking me with a soft but firm shield, gray but shimmering with silver.

“What was that?” I wondered to myself. Inside I felt peace, an expansive calm, so unlike my usual descent into sad doubt. “What the heck was that?” It felt like my heart finally had protection, not a hard shell of cynicism, but a soft shell of loving care.

There have been other occurrences since consulting the shaman. A monarch butterfly flew right near our window one morning, the first monarch I have seen in our yard possibly …ever. My brother Marc and I loved monarch butterflies when we were small. We read about them; we caught them in butterfly nets and released them back into the sky. Every time I see a monarch butterfly, which isn’t often, I think of Marc.

That butterfly flew right near me for a markedly long time. Or was it a Marcedly long time?

This week, I was almost in a possible plane crash, but I wasn’t.

I just saw two hummingbirds and I never see hummingbirds.

Of course, these experiences could be explained away as coincidence or meaningless phenomenon to which I have erroneously attached sentiment. I was trained as a scientist and raised by skeptics. Sure. I cannot argue with that line of reasoning. There is no proof, and all these “coincidences,” seen through the cold lens of logic sound naive and silly.

But here is what I think. There is a great deal that we cannot possibly know, with our limited human brains and our mere five senses. The world is vast, and we are far more connected than we can perceive. There are wise people who know a lot, and I am inclined to listen respectfully.

As for me, my intent is to travel the path I am meant to travel, doing the work I am meant to do, with a deeply loving but newly protected heart (thank you Shaman!), for as long as possible.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

July 15, 2022

Six Calming Strategies for Dark Times

“Now is the winter of our discontent.” Although I quote Shakespeare, I really only know this line from my ninth grade obsession with the movie The Goodbye Girl. I should try to read Richard III but I am too busy doom-scrolling. Now is the summer of our discontent, and our discontent is pervasive. Gun violence is so common that small shootings are no longer newsworthy. It takes a mass shooting to possibly garner media attention, but there have been over 300 mass shootings in 2022 already. Yes, 300.

Many people I know are overwhelmed with negativity. Pick your fear: gun violence, inflation, loss of abortion rights, racism, immigration, the end of democracy, the end of this very planet. It is particularly easy to be swept up in negativity and pessimism, with 24- hour news cycle.

The news almost always focuses on disasters and crises. News organizations are well-aware that fear keeps viewers engaged. “Today, in breaking news, a 12-year old girl was kidnapped walking home from school” will glue viewers to their seats. If the anchor chirps, “Happily today, all the children arrived home safely” most viewers will shut off the TV and go eat ice cream. So bad news plays, non-stop. Bad news guarantees viewers.

“Be afraid, be very afraid,” my husband and I mutter to each other, reassuring ourselves again and again that the world is not as dreadful as we are being told.

Lest you think otherwise, I fully acknowledge there is plenty to fear; there are perilous issues in our world. However, living your life in fear hurts your mental health. Living your life in fear creates anxiety, depression, and panic. Living your life in fear creates suspicion of your neighbors and the strangers on line at the grocery store. Fear also affects our physical health, leaving us more prone to illness, cardiac disease, and cancer.

So, if you would like to reduce fear and embrace calm, here are 6 strategies to help:

Limit the TV/radio news: It is important to be informed, but you don’t need to be informed all day long. Centuries ago, news would arrive at a small village only when travelers came, maybe just once or twice a month. Imagine the relief of listening to the news just twice a month! I recommend listening to the news at the top of the hour once or twice a day, and then turning off the TV or radio. The allure of checking the news is powerful and a bit addictive. Try to keep it to a minimum. Another tip: many people find reading the news to be less jarring.

Listen to music instead: Music fills the air around you with beauty, instead of gloomy tragedies. Listening to songs you love will lift your spirits. Do you like 70s music? Turn it on loud and dance to Earth, Wind and Fire. Do you like Madonna? Come on, vogue, baby. You can regularly find me singing the harmonies to Beatles songs or dancing (badly) to A Chorus Line. Singing along makes me smile, every time.

Notice the good: Our brains naturally focus on problems and worries. That is how we evolved, and it has kept our species alive. The caveman who stayed alert and heard the approaching bear survived; the caveman who napped by the fire did not. We are evolutionarily wired to notice problems. However, we pay a steep price for this negative focus. When we dwell too long on negativity, our bodies tense, our cardiac system goes into over-drive, and our immune system shuts down.

There are plenty of positives around us, but we often overlook them. Right now, I notice that I am comfortable sitting on my couch, that my beloved terrier Frankie slumbers next to me, that my living room is graced by a grand piano, that I ate healthy yogurt and fruit for breakfast, I am pain-free, and I live in a free country. That is a plethora of goodness, for which many people around the world would be overjoyed, but which I can easily take for granted. I imagine you might take gifts for granted too.

Get outside: I am fortunate that Frankie, the aforementioned terrier, requires daily walk. Many days, I grumble about having to take him. And yet, I am no sooner out of the driveway when I notice my mood lifting. I love watching Frankie’s little ears bobbing up and down as he trots, his feathery tail proudly aloft. Walking, breathing, seeing the flowers, and waving at neighbors all bring me joy. Nature grounds us. The enormity of the blue sky, majestic trees, pounding waves, distant mountaintops, all these sights remind us that we are but a small part of a vast and beautiful universe.

Make your garden grow: I don’t mean an actual garden (although gardening is an excellent hobby if you enjoy it). This phrase references Candide, a book by Voltaire, yet another classic book which I never read, but I have seen Candide, the musical. In the show, Candide explores the world seeking enlightenment but encountering evil and suffering instead. At the end, he concludes that the wisest plan is to tend his own garden, meaning to build a good, meaningful and healthy life for himself and his wife.

Tending one’s garden does not necessarily mean turning your back on the world. Hopefully, our gardens grow, and we feed each other from what we create. My garden, for example, includes this blog, my outreach to readers near and far, and my wish to nourish compassion, kindness, and bravery. Gardens can be about growing vegetables, but also growing empathy, financial generosity, and artistic creation. In these small but significant ways, we better our world, a little bit at a time.

Embrace hope: Humankind has endured many dark times. People have survived world wars, plagues, enslavement, and many more horrors. We are more resilient than we fear. Hope is what carries us through the darkness. Having hope doesn’t mean pretending that everything is great. It means holding out hope that things can turn out OK, someday.

In the myth of Pandora, Pandora impulsively opens a box which she was warned not to touch. Once that box is opened, out fly all the world’s tribulations: evil, greed, want, envy, sickness, and death… forever to torment us. But one other force emerges from the box. That force is… hope. Hope that we can survive. Hope that we can help each other. Hope that our gardens might nourish each other through a dark day, and that better days could still be ahead of us.

If hope sounds naïve, I remind you that hope is what carried many people through the grimmest of times. Enslaved people sang songs about freedom and justice, Martin Luther King had hopes and dreams of a better world. Right now, the Ukrainian president Victor Zelenskyy speaks passionately about hope for his embattled county. Hope can sound naïve, but it is the bedrock that sustains us when we suffer. Hope fuels our energy to keep pushing on.

My hope for you, dear reader, is that these suggestions bring you some comfort and tools to carry with you. Look out for one another. Forge on, stay safe, and be well.

(A previous, somewhat less personal version of this essay is currently in PsychologyToday.com)

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

June 17, 2022

Come on Charlie

By Ken Giglio, guest author

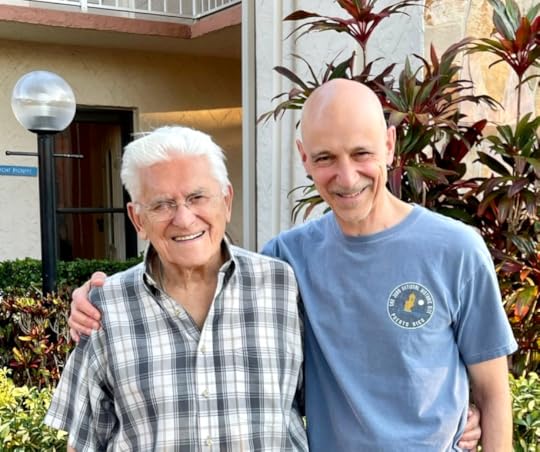

Every time I leave Florida and my 96-year-old father, like I did two weeks ago, I wonder how many more days he has until eternity. I joke with him that his age is a pre-existing condition. My joking is, I realize, a way to make light of my fear of the inevitable, for my father, Charlie, death is clearly closer than for most. Maybe the real joke is to think death will come first to the oldest among us.

Being with my father, I noticed how increasingly unsteady he is. I watched him shuffle and sway as he walked short distances without his walker, which he often stubbornly leaves behind. Straining to stand, I heard his coaxing voice, loud enough for anyone nearby to hear, “come on Charlie.” Once he pulled himself up to standing, we went about our day, starting with a trip to his favorite breakfast spot. Watching him get into the car, a set of maneuvers using his stronger arms to angle his shaky legs and butt onto the seat, I heard again, “Come on Charlie.” His tone was encouraging and pushy, without any judgment that I could pick up.

I’ve been hearing my father talk to himself for years, with only these words or variations on the theme always ending with his name. I can’t remember when I first noticed it, but I somehow associate this out-loud self-talk with more recent times and situations where he needs to push himself against the physical realities of old age.

At breakfast I asked my father when he started talking to himself in this particular way. I was really curious if it started out as an interior voice, which we all have to some extent. Yes, it did start in his mind, he told me, but quickly escaped and became vocal. He shared that the self-talking started when he was in the army as an 18-year-old stationed in Belgium during the Battle of the Bulge. His best army friend Cal, who he called a great foxhole buddy because he trusted him not to run away when under enemy attack, was redeployed to another division. “It depressed me,” my father said, “not to have Cal around, and I needed to talk myself out of it.”

He related the story I’d heard many times before about the bitter cold of the front lines in Belgium in January 1945, as the German troops repeated a pattern of retreat and counterattacks exhausting the American troops. This time the telling of this story was different, there was something in the telling I’d never heard before. My father had been lonely and depressed without Cal. He had lost other comrades to snipers and endured frostbite, but losing Cal was the hardest part. Still a teenager, he persevered by talking himself through that forced separation and the brutal months that culminated with his witnessing the evil of a Nazi concentration camp.

“Perseverance is a choice,” the writer Margaret Wheatly reminds. “It’s not a simple, one-time choice, it’s a daily one. There’s never a final decision.” For my father as an infantryman and as a 96-year-old, “Come on Charlie” was and is a mantra, a way for him to be there for himself every day. When I hear him invoke his name often with a determined grimace, I hear grit mixed with self-compassion. It seems he’s pushing against his aging body and mind and at the same time accepting it all.

“It’s about giving yourself that extra push,” my father explained while eating an egg croissant sandwich at his second favorite breakfast place, Panera Bread. He continued, “each situation is different and needs a different push. When you find yourself getting too lazy, you push yourself because you have some responsibility that your expected to be doing. You talk to yourself; you get off your ass,” he finished.

His emphasis on so much pushing made me feel pathetically lazy. I scanned my own responsibilities, like some writing projects I was procrastinating about. I also wondered again, as I have many times, how I will persevere as I age. How will I lift and straighten my body when it’s stiff and deal with loneliness when I lose the people I depend on and love? Watching my father pointing his crooked arthritic finger into the air to make a point, I realized there’s more to learn about life from this strong and wise man.

Spending time with my father has brought me closer to understanding the real meaning of perseverance. Watching how he takes on life has allowed me to leave behind a lot of “being angry at life for being life,” as the author and Buddhist teacher, Pema Chodron puts it. I’m grateful for this new way of seeing life, because, like Charlie, we have all had hard living, giving us the need to persevere. I’ve never had to face enemy snipers hiding in the forest across a frozen field, and yet the life has given me plenty to be afraid of. Unlike Charlie, I didn’t grow up poor on the lower east side of Manhattan to immigrant parents. I didn’t lose my father to alcoholism when I was 12, and witness one of my bothers die from a tooth infection and the other institutionalized because his developmental disability was too hard for his widowed mother to manage. And, unlike my father, I didn’t lose my wife of 55 years to ALS. The woman Charlie serenaded on a on Kenmare Street in Little Italy after coming home from the service, my mother, Rose, died in 2007. So long ago but somehow so near to today. We all persevere.

A memory comes to me: I’m probably around 8 years old. Our new white Mercury Comet station wagon with the red interior had just pulled into the driveway. We were all proud of that car. It’s dark out and late; my siblings are asleep next to me in the back seat. From where I’m sitting on the far side of the car, I watch my father carry my 3-year sister up the front steps and into house. He’s holding her carefully, gently cradling her small form. He reappears for my bother next, the middle 5-year-old. He’s less gentle but still careful. My brother’s legs dangle and sway a bit as my father takes the stairs again and disappears into the house. I’m next, the oldest, and I wait in the dark wondering if I’ll get a wave in from my father as her reemerges from the house or if he’ll come and carry me in, too.

In that moment I decide to lie down and feign sleep. I wait for what feels like a long time until I feel a light tap on my leg. “Come on Kenny,” my father says in a gentle but firm voice, “I know you’re awake.” In this reimagined memory, he gathers me up in his arms and carries his anxious and creative oldest child up the stoop steps and then all the way up the interior stairs to my room where he lays me in bed and tucks me in.

Ken Giglio is an author and principal of Mindful Leadership, a global executive coaching and leadership consulting firm. He’s a New Yorker living in Bucks County, PA.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

June 8, 2022

Learning Differently or, "The Candyman Can"

Once upon a time, I gave birth to a perfect little girl, with big blue eyes and a wide smile. She exuded peace and serenity. A friend of mine, who is psychic, visited us after Anna was born. Gazing into Anna’s exquisite face, my friend murmured, “She is an old soul.”

As my baby grew, I noticed that she was. . . quirky. On the one hand, she dazzled us with her vocabulary, and communication skills. Keenly observant, and eager to please, Anna was always her preschool teacher’s favorite.

“She gives the best back-rubs,” purred one teacher.

“She is practically perfect in every way,” pronounced another.

On the other hand, Anna was not a traditional learner. Before starting kindergarten, she was supposed to memorize her home phone number. We rehearsed the number again and again, but she couldn’t do it. Each time she failed, her little face fell, formerly bright with an expectant smile. It frustrated her and mystified me.

One August morning, we relaxed in the backyard, while I pushed her on our tin red and blue swing set. Back and forth she swung, attempting to recite the 10-digit number, blond pigtails bobbing in the sunlight. After weeks of practice, she still couldn’t get it. Suddenly, I had an idea.

We had been listening to “The Telephone Hour” from Bye Bye Birdie. For those of you who don’t know it, the song starts like this, “Hi Nancy, Hi Helen, What’s the story, Morning Glory?...”

Unlike her phone number, little Anna knew these lyrics backwards and forwards. Impulsively, to the same tune, I began singing, ‘2 1 5, 3 2 1, 5 4 1 3” and stopped. “Now you sing it.”

Anna’s high clear voice rang out, “2 1 5, 3 2 1, 5 4 1 3!” She never forgot her phone number ever again.

This was one of several learning quirks Anna had. I think she was in middle school before she could reliably recite the four seasons in order. Yet, she sailed into the academically gifted program. I couldn’t explain the dichotomy, but I did my best to embrace it. Besides, she had a whole new old-soul gift emerging.

In first grade, Anna made a friend named Steven (not his real name). Steven was a sweet skinny boy with a serious speech impediment, and he could not pronounce “R” well. Shy and awkward, Steven did not connect well with the other boys. However, 7-year-old Anna befriended him and they became pals.

One day at recess, the class ran out to play in the grassy field. The other boys gathered to kick a soccer ball, leaving Steven far behind. Anna stuck near her friend. “Let’s pretend like we are lions,” Anna suggested.

“OK.”

“You first, Steven. You are a lion. So, you have to roar. Shout RRRRRoar!”

“Wwr-oa” yelled Steven. In that way, Anna, quite intentionally, got her friend to do speech therapy exercises during recess. No one asked her to help him or suggested this strategy to her. She created it on her own, her first health intervention, but not to be her last.

Toward the end of first grade, Anna was invited to Steven’s birthday party, even though she was the only girl there. His mother approached me, smiling.

“Are you Anna’s mom?”

“Yes, I am. Hello, it’s nice to meet you. Thanks for inviting Anna!”

“Steven talks about Anna every day. We are so grateful to her. You have no idea what it’s been like for him.” And Steven’s mom began to cry, tears of gratitude streaming down her face. We cried together.

***

By the time she hit high school, Anna decided she wanted to be an occupational therapist. We thought this was a brilliant career choice, as it would build on her old soul strengths of perceptiveness, compassion, and creative healing. Still, occupational therapy would also require statistics, biology, chemistry … all subjects heavy in memorization. It wouldn’t be easy.

Junior year, Anna struggled with Algebra 2. Despite her efforts, she had trouble understanding the concepts. I reached out and called a math tutor. On the phone, I struggled to convey the problem, “Anna is incredibly smart but sometimes she learns… differently. I can’t explain it exactly. Sometimes she needs concepts presented in a radically different way. Let me tell you how she learned her phone number…” I launched into the story of Anna, the backyard swing, and the song.

“I get it! Perfect, I can do this!” exclaimed the tutor.

“You can make up songs about algebra?” I asked, dubiously.

“You bet I can.” And she did! Somehow this tutor translated Algebra 2 into song and dance. I never knew how exactly, although I frequently overheard Anna and the tutor laughing together. Dancing and singing, Anna passed Algebra 2 with flying colors.

***

Fast forward seven years, Anna just graduated with her master’s in occupational therapy from one of the top programs in the country. It was a long and challenging road, although to be fair, some classes could not have been easier. For example, psychology and communications were so natural she barely had to study.

Anatomy, on the other hand, reduced her to tears. It was the same dichotomy as when she was little: anything having to do with people was a piece of cake. Anything having to do with rote memorization was inexplicably hard. But, knowing her own learning style, Anna devised her anatomy . . . dances. Hand on a hip for this bone, hand on a shoulder for that one. Class by class, test by test, Anna persevered. Finally, she arrived at clinical placements.

Anna’s first placement was on an intensive care unit in a city hospital in the middle of COVID. Imagine the wall of death, ventilation, vomit, blood, and defecation that hit her, all at once. Imagine being 23 years old, living in a strange city, encountering such devastation. Anna went into emotional shock briefly, but quickly bounced back. Once she calibrated to the grimness of the ICU during covid, the creative helper in her reemerged.

“Mom!” She called one afternoon. Her voice chirped with joy.

I put my notes away and sat back to talk. “Yes? What’s up?”

“So, there was this young girl in the ICU (details changed for her and other clients described). She was developmentally disabled, blind, and all alone. She couldn't talk much, but she kept repeating this one phrase, ‘The Candyman can. The Candyman can.’ And everyone is saying, what the heck does that mean? But I knew. I started singing to her, “Who can take a sunrise? Sprinkle it with dew. Cover it with chocolate and a miracle or two. The Candyman. The Candyman can.” And she settled right down. The more I sang, the calmer she got, so I just sang ‘The Candyman’ all day.”

For three months, 23-year-old Anna worked the ICU. She motivated a man unwilling to do his exercises because of intense pain. “It hurts!” he yelled, “it hurts!”

“I know it hurts, but let’s do the exercises,” said another therapist.

“YOU DON’T KNOW! You DON’T know how much it hurts!” The room fell silent.

Anna knelt in front of the man’s wheelchair, and locked eyes with him. “You are right. We don’t know how much it hurts. I’m sure it hurts terribly, and I am sorry for that. We are trying to help you get home. If you do these exercises, even though they hurt, you will be strong enough to go home. So, will you do them?”

He did.

In Anna’s second clinical placement, she helped refugees adjust to life in the United States. One of her clients was from Afghanistan, and he could not read either Farsi nor English. Distressingly, he couldn’t read his own mail. Although he had been in the program for awhile, no one had figured out how to help, other than giving him programs that painstakingly translated one word at a time.

But. . . the Candyman Can. After research, Anna discovered an app that could “read” the English mail, and “say” it aloud to the man in Farsi. The man tried the new app and realized that the letter he was struggling to decipher was just a piece of junk mail. Anna snapped a photo of him, joyfully dumping his junk mail in the trash.

***

We are all wired differently. Some kids learn easily through traditional classroom instructions, sitting quietly in their chairs, hands folded, attentively listening. But other kids… don’t. That’s just not how their brains work and not how they learn. Some kids need to learn while they are running or dancing. Some kids learn while they sing or some other unique approach. We can’t help them by forcing them to learn the way other kids do.

I wish that every child who learns differently could receive attuned parenting and education. Most of Anna’s success is due to her grit, hard work, and determination. She also succeeded because she had people who believed in her. I am a psychologist, so I had a sense of how to help my daughter flourish. I was also lucky enough to be able to raise her in a great school district, and to be able to afford that math tutor. It pains me to think of all the kids who learn differently, without these supports, who leave school feeling defeated because they never understood Algebra 2.

If you know a child who learns differently, keep engaging. Try new things and keep looking for what works. Love them and look for their gifts. I bet they are in there, somewhere, those little gifts that make them special. Like the Candyman said, “Mix it with love.”

You never know how far a child can go.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

May 28, 2022

Remembering on Memorial Day

On Memorial Day, we honor our nation’s fallen. I would like to write about those who gave their lives defending our country. However, I personally only know one person who lost their loved one in a war. One.

My family served. My uncle Greg served in the navy in World War II, and his wife Adelaide was a WAVE. They met at a Navy base in Pensacola, where they trained soldiers for combat. My Uncle John served under General Patton, stormed his way through Europe and fought in the Battle of the Bulge. I barely know any of his stories. We lived far away and saw him once a year. When we did get together, instead of sharing his war stories around the dining room table, we all played Social Solitaire. His generation saved the world, came home, and just got on with their lives.

My father was drafted into the army after college. He was a gifted musician and a sensitive guy. The army took one look at him and thought... hmm. First, they trained him to be a telegraph operator, but the dots and dashes always sounded at the same unvarying tone. Dad couldn't bear it. Eventually he became the conductor of the chaplain’s choir at Fort Dix. For three years my Dad conducted and wrote fantastic 3-part men’s arrangements of songs (“Tommy’s Gone to Ilo,” “The Leaky Boat”) Some men fought at Iwo Jima; others arranged choir music.

Personally, I don’t know a thing about what it is like to fight and die for this country, beyond what I saw in Saving Private Ryan and Band of Brothers. As a psychologist, I do understand what soldiers have to manage emotionally to fight. In battle, it is imperative not to be awash with panic and terror. The only way to accomplish a battle objective is to keep focusing on the goal. If a person stops to say, “My god, this is awful. How did I get here? I’m terrified!” he/she will never be able to do what the entire unit is counting on him to accomplish. I have worked with many men who learned to quash their emotions to survive.

Soldiers learn to push feelings down. They learn through repetitive drilling. They learn through arduous training. They learn through role modeling, which can involve mocking the sensitive. They learn how not to feel, but it comes at a cost.

Many a war veteran has landed in my office, with an alienated spouse. Their wife (it is usually the wife) is looking for emotional connection, for intimacy, and sharing. The veteran no longer even understands what his wife is talking about. “I’m reliable. I support us. I don’t have any feelings to talk about. I’m fine. Why aren’t you?” Once people learn to suppress their feelings to survive, it can be hard to turn feelings back on again.

In the 1990s, I worked in a rehabilitation hospital. Quite a few of the patients were aging World War II veterans, some of whom had developed dementia. I remember one proud veteran who talked non-stop about France, Belgium and Germany. I heard many gruesome battle stories about his buddies who died and how he managed to survive. Later, when I met his family, I remarked on the veteran’s vivid battle tales.

“He talked to you about that?” asked his wife, with a shocked tone.

“Yes, he was spell-binding. Doesn’t he talk to you?”

“We have been married for 50 years and I never heard one of those stories.”

I don’t think this veteran shared his war tales with me because he was grateful to have psychotherapy. I think he talked to me because he had mild dementia, which lowered his learned inhibitions, finally allowing him to speak. He no longer remembered the military training of “we don’t talk about feelings.” This training had fallen away, and now he could finally share what he had been through.

I don’t know what it is like to serve. I know that I myself would make a terrible soldier. I am too emotional, too sensitive; I have never even been in a fist fight. I don’t know what it’s like to lose a loved one to war. My family fought, but we were fortunate. Conducting the Fort Dix choir is not a death-defying act of service.

Aren’t we lucky, all of us who don’t know what it’s like to fight in a war? Aren’t we lucky to be secure in our homes, able to feel our feelings, able to go on with our ordinary lives and ordinary problems? Other people carry that load for us, other people, and other families.

If there is anything in this piece that sounds ignorant about wartime, I apologize in advance. I truly am ignorant about wartime. Despite this ignorance, I honor the military. I know that my ignorance is a privilege. To all the military and their families, thank you for your service. May we remember those who laid down their lives for us, on Memorial Day, and on every day.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

May 20, 2022

What is Your Purpose?

What brings meaning to your life? I am not asking because I have the right answer. I am asking because I want you to have an answer, an answer that makes sense for you. Making meaning from your life’s experiences is associated with resilience, the capacity to bounce back from life’s hardships. Having a sense of purpose is also correlated with happiness in life, much more than career success or material possessions. (read more here: https://www.pursuit-of-happiness.org/history-of-happiness/martin-seligman-psychology/). So, what gives people a sense of meaning?

Some people get meaning from their work. Firefighters, EMTs, and our military all work to rescue others and to keep us safe, which can bring intrinsic purpose. Teachers, doctors, nurses, and therapists often feel deeply rewarded from helping vulnerable people, and offering them care, hope, and tools to improve their situation. I myself usually feel meaning in my work, although sometimes I wonder, “Am I helping? Does it really matter?”

I feel deep satisfaction when I wrap up a successful case. In the final session, the client and I celebrate the growth he made. We review his progress in therapy, and how much better he feels. Perhaps the client gets a little teary, and thanks me for being there for him. Those moments leave me feeling deeply satisfied. These are the times I know I have made a difference. It is perfectly clear; right in front of me.

But sometimes another dynamic happens. I hear from a former client, someone I worked with five years ago, someone I didn’t even work with that long. The old client calls, perhaps because she is referring someone else to me. The former client says something like, “You helped me so much. I will never forget when you said…”

In my mind I wonder, “I helped that person? I didn’t think I helped her. I don’t even think I said that to her.”

Out loud, I say, “I’m so glad, thanks for telling me.”

It happens frequently that I had a positive impact when I thought I wasn’t having any impact at all. Couples return to me after years after their therapy; couples I feared would probably divorce. “You saved our marriage.”

(“Did I? Wow, I had no idea.”).

“I’m so glad. Its good to see you. How can I help you now?”

The meaning of my life is to use the tragedies I have endured, the losses that I lived through, the deaths of the people I loved, all for good. Each of these tragedies expanded my capacity for care and empathy. Each loss increased my ability to understand others' losses. Armed with my own tragic past, I can witness others who are in pain. I can sit with them and bear their misery. And I can also say, either silently or sometimes out loud, “You can get through this. You can bounce back. Life goes on. Do not give up.”

That is my purpose. What is yours? There are many purposeful paths, so many that I can’t list them all. Some people are artists, using their talent to spread important ideas and values. (I just saw Fairview, a play about racism, which impacted me profoundly.) Other artists create beauty which lasts for centuries. (I listen to Debussy’s Clair de Lune, written 150 years ago, and my heart swells at the opening notes). Some people garden, carefully planting flowers and trees, freshening the air and creating blessed shade for centuries to come. Some people take tender care of their aging parent, sacrificing as they give back to the mother who cared for them. Most people are passionately devoted to their children, creating the new generation of our world. And many people get their life’s meaning from their faith’s values, spreading God's love and teachings.

Any kind of work can be meaningful, depending on your mindset. The cook who creates our delicious dinner has nourished our body and soul. The finance expert who manages of our savings so that we can safely retire; every job has a purpose. Still, if you don’t feel meaning in your work, there are other ways to find it. There is volunteer work, family, friendship, and just plain human kindness.

There are a lot of folks, who have endured great trials, who now use those experiences to help others. In my town, there is a family who lost their son, and now run an organization to create awareness about concussions. Many people run in annual races to raise funds for cancer, because they themselves lost a loved one to cancer. These people are taking their own tragedy and transforming it into a purpose. They have not only bounced back; they have bounced back with increased meaning and purpose. That is resiliency.

There is a certain phrase that makes my blood run cold. I have heard this phrase many times in the course of my work, and it signals grave danger: “Everyone would be better off without me.” This phrase signals not only lack of meaning, but the sinister opposite; the idea that one’s very existence is harmful. These people are a great risk for suicide.

I have lost four family members to suicide. I have also worked with many people who have survived the suicide of a friend or relative. I can assure you that no one ever says, “I am now better off without them.” No one.

(If you yourself are thinking about suicide, or feeling that others would be better off without you, please click here for help: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/)

No one can tell you the purpose of your life. That is a deep question for us all to ponder. What I can say is that I think all life has meaning. We touch each other, in ways large and small. We can help each other, and gain meaning from being helpful. We can create art that moves people. We can raise ethical and kind children. We can shovel our neighbor’s snow when they are sick. We can simply be there for each other, providing companionship and company.

A few years ago, I was having one of those days in which everything went wrong. My computer stopped working, and I couldn’t fix it. I got into a fight with my mother. I had a splitting headache and I was late on my way home. It was pouring rain, but I had to stop at the post office to mail an important letter, which delayed me further. I idled behind a line of slow cars in front of the postal mailbox.

I seethed.

A postal worker popped out from the post office. She wore a heavy black coat, and she hurriedly gathered the mail from the mailbox, rain pouring off her back. But she glanced over and saw me waiting. Quickly, she stood up, trudged through the pouring rain, and held out her hand for my letter. Her dark hood almost covered her face, but I could see her bright smile, beaming with kindness. I rolled down my window, raining streaming in through the opening, and handed her my instantly sodden letter.

I have never forgotten that moment. Was it so important? Not really. But this postal worker changed my day. She single-handedly changed me from feeling aggrieved to feeling gratitude for her unexpected thoughtfulness. I can still see her beaming smile.

I am sure that, if you asked that postal worker, she would have no recollection of this moment. Just like me, when an old client calls and thanks me for saying something, she might think, “I did that? Did I? And it was that important? Really?”

But you see, that’s the point. We never know when we can have a hugely powerful impact on others. Our kindness, our help, our art, our parenting, our volunteering… all of it matters.

What’s your purpose?

#resilience #meaning #purpose #psychology

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

May 4, 2022

Hey Hollywood – Scars Don’t Make You Evil

At the end of a weary work week, I sprawled on the couch ready to watch a movie. I wanted to be entertained by someone else’s problems which I was not obliged to cure or support. The Batman seemed a decent choice for escapist fun.

All went well until the Penguin appeared. Then, I saw Colin Farrell, unrecognizable in a fat suit and made up with… a prominent scar. “Look at that,” I sighed to my husband. “The Penguin now has a facial scar.” To be clear, the Penguin has no backstory of being scarred. This scar was new, unexplained, and entirely unnecessary to the plot.

I am a burn survivor and clinical psychologist. It is well-known in the burn community, yet somehow invisible to others, that villains in movies are often disfigured. Facial scarring defines some of the most infamous movie villains of all time (Darth Vader, Freddie Kruger, Voldemort, and the Joker to name just a few). Movies rely on an unconscious and pervasive assumption which equates beauty with good, and disfigurement with evil.

Perhaps, movie heroes will always be beautiful and unsullied. I accept that, although I find it unfortunate. (Many of the best people I know are a bit chubby, wrinkled, and balding.) However, why must villains be disfigured? Can’t they just be ordinary looking people who are nasty? Can’t they simply act their inner issues rather than cheaply signaling their evilness with a prominent scar? Isn’t this a trope? Perhaps they should all maniacally twirl their mustaches instead?

I cannot think of any other marginalized group that is still so uniformly maligned in movies. For example, Black characters in film might be heroes or villains. Gay characters are no longer written as stereotypes. Overweight characters can be good or bad. Most of our marginalized groups now enjoy nuanced portrayals in film. It would be unacceptable otherwise, and writers and movie makers now accept this new standard.

Somehow, though, the portrayal of disfigurement has escaped notice. No one seems to object when disfigurement is used, repeatedly and unrelentingly, to signal moral failure and evil intent.

There are groups working to address this issue. Face Equality International is a group of NGOs, working to combat prejudice against the facially different (by the way, May 17-24, 2022 is Facial Equality week.) FEI has campaigned since its conception to prevent further harmful characterization of those with facial differences. An open letter challenging the casting call for people with disfigurements to play non-human characters in the Amazon Prime adaptation of Lord of the Rings can be found here.

Today it occurred to me that the best way to effect change in films might be to address the movie-making community directly, and screenwriters in particular. Writers lay out the vision of the film; imagining the look of each character; it all starts with them.

First, allow me to set the stage.

Imagine, for example, you have a daughter, a little girl, burned in a horrific fire. Imagine you sat by her hospital bed for many months, watching her heal and praying that she might somehow still have a good life. Now, years later, miracle of miracles, she is scarred but well. What movies do you want her to watch?

Beauty and the Beast? (In which the good character is literally named Beauty, and the Beast is turned ugly when he is mean, and handsome again when he becomes nice.)

The Lion King? (The disfigured villain is literally named “Scar.”)

Star Wars? (Where evil Darth Vader hides his hideous, burned face behind a mask)

Harry Potter? (Voldemort – is as dastardly and murderous as they come – also disfigured)

The Hunchback of Notre Dame? (in which Quasimodo is not evil, but his disfigurement renders him so pathetic that he is forcibly hidden away from society).

Wouldn’t you want your daughter to have some representation, somewhere, of disfigured people who are neither evil, nor pathetic, just ordinary people leading ordinary lives of love, worth, and purpose?

Disfigurement doesn’t make a person evil. It arrives at birth, or from trauma, and leaves the person with social challenges for the rest of their life. Hollywood isn’t helping.

I ask that you lay the disfigured trope to rest. Let your actors playing antagonists use their prodigious acting skills to portray badness. They don’t have to be ugly on the outside. Surely your cast is more than capable of acting evilness without attaching a fake scars to their cheeks.

Please write those characters instead.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

April 18, 2022

On Giving & Receiving Criticism, or, What Dylan Said

I don’t handle criticism well. My gut reaction is usually a torrent of justification, a quick defensive shield. My throat gets hot and my voice rises. I want to immediately establish that I am good, benevolent, misunderstood, and decidedly underappreciated. Although I have been in therapy, and I am not young, I still find it difficult to respond differently.

I woke up this morning feeling expansive. The sun peaked over the horizon, which was a robin’s egg blue. I sipped hot coffee and petted my terrier, Frankie, trailing my fingers in his soft white fur. I thought to myself that I should really count my blessings. Then, I opened the “Good Reads” page for my memoir, Flashback Girl. The book had 73 ratings, averaging 4.5 stars; really well done! My author heart soared, until I read this:

“This is a memoir by Dr. Deguire . . . Amazingly, she survived but in her own survival, she endured constant family traumas and losses. Most tragic was the suicide of her beloved brother, Marc, that haunted Lise throughout her life. However the author writes about her overcoming these struggles, the most disturbing aspect is her relationship with her mother. She is painstaking in describing her mother’s shortcomings (and indeed, Kathryn had many), but even with her training in psychology, Lise seems blind to the fact that her mother clearly suffered a psychological disorder that likely impaired her ability to be emotionally supportive of others, including Lise and Marc, her own children. Lise’s story certainly shows her amazing triumph and resilience but for me, it falls a little short on genuine insight and empathy.”

(2 stars)

My gratitude for the morning vanished like a chased rabbit scurrying down a hole. My body shook, and my breath got shallow. "Even with her training?" “Blind to the fact that her mother clearly suffered a psychological disorder?” “Short on genuine insight and empathy?” Ouch.

Rationally, I should not be upset this comment. The vast majority of reviews on Good Reads were 4 or 5 stars, glowing about Flashback Girl. Logic would say that some people won’t like some books. Logic would say that some people won’t respect my point of view, just as I sometimes struggle to respect other people’s.

Logic would say that we do not all share the same understanding of empathy and forgiveness. But that, my friends, is for another blog.

This blog is about giving and receiving criticism.

***

It is well-known in marriage therapy that thriving relationships require a 5:1 ratio of positivity to negativity. Dr. John Gottman observed marriages and found that he could accurately predict (by 90%!) couples who would divorce by whether they displayed this 5:1 ratio. The positive behaviors could be small: a smile, a nod, a pat on the shoulder, a proffered cup of coffee. The negative behaviors could be equally small: a frown, a sigh, an eye roll. The major takeaway is the people need to experience much more positivity than negativity to feel loved and safe.

Five to one, you say? Isn’t that a whole lot of positivity? Is that even possible? Yes! Think of how we interact with little children. With our kids, we are mostly smiling, hugging, and cherishing. When they burst into our office in the middle of the work day with a ridiculously drawn picture, we don’t roll our eyes, frown, and exclaim, “What IS that? Can't you see that I am busy?” Instead, we smile and thank them for the picture. We comment on the colors they chose and ask them to tell us about their drawing. Then we hang their ugly scribble on our wall. That is 5 positive behaviors, and 0 negative ones, a 5:0 ratio. We understand, intrinsically, that children require this level of affection.

The thing is, we all have that little kid inside us. We all have a child within us who needs to feel profoundly loved and cherished. That little kid never goes away, not even decades later. We all need this level of warmth to sustain the toxicity of criticism.

When I conduct marriage therapy, I always start sessions with an “appreciation.” This is a time that each person shares something they liked about their partner over the week. This appreciation is crucial because most people commence marriage therapy in a defensive crouch. They fear the criticism they imagine is coming. And there undoubtedly are some behaviors that will need changing. If, however, couples start the session feeling valued, they are more likely to respond positively.

I am the same way. If my husband simply says, “Why didn’t you take out the trash?” my response is likely to be 1) “I was very busy and let me tell you how busy I was” (defensive) or 2) “Well, why didn’t YOU take out the trash?” (defensive and counter-attacking).

However, if my husband says, “Thank you for doing the taxes. I know you put a lot of time into that. I do wish you could have taken out the trash too.” Then, feeling appreciated, my response is likely to be, “I’m sorry, I didn’t even think about it, but I will try next time.” It is vital to speak with appreciation and positivity, instead of focusing solely on criticism. That is how you can get people to truly listen to your feedback.

***

That brings me back to my review situation. Even though Flashback Girl is 4.5 on Good Reads, the reviews that stick with me the most are... the negative ones. Generally speaking, these negative reviews focus on my complex relationship with my complex mother and my depiction of her. Fair enough, I guess, from a rational perspective. I predicted this would be the most controversial aspect of the book.

People often respond to my relationship with my mother through the lens of their own history, unable to imagine that mothers can be profoundly different. Just because a woman is a mother does not mean that she is psychologically equipped to be a good-enough mother. Some mothers do immense damage, intentionally or unintentionally, damage so powerful that it destroys the parent-child bond itself. Sometimes that damage is so toxic that one can not continue in the relationship without imperiling one's own stability. That was my situation, and I did my best to explain it. However, the reviewer took my words as being ungracious and "unempathic."

Since Flashback Girl came out, I have received letters and emails from many people, all positively, thank God, because how I would handle it otherwise? The largest group of readers, predictably, have been my fellow burn survivors. The second largest group surprised me. The second largest group have been people who had difficult mothers. Many of them said that my book was a lifesaver, because so few people write honestly about this issue. Many of them said it was a profound relief to read the book, because it validated their own pain, disappointment, and difficult choices. Most of them hid their truth or downplayed it. But it is excruciating to be poorly mothered, and then to have to hide that pain because 1) No one understands, or worse, 2) People criticize you for not being more forgiving or understanding of the very parent who repeatedly devastated you.

As Bob Dylan once wrote, “Come mothers and fathers throughout the land. And don’t criticize what you can’t understand.”

Some evolved souls would gently nudge me toward detachment. I have read about famous artists who refuse to read any reviews, saying that they neither believe the positive reviews nor the negative ones. I think those artists are both wise and, also, have probably had a lot more reviews than I, so maybe they are over it.

I should get over it.

OK, so let's try something. If I were to reframe this critical review, in the way that I counsel couples, it might sound like this:

Opening Appreciation: I see how hard you try, Lise, in your work, your writing, and doing those taxes. You even helped take out the trash this morning (I did!).

5:1: Your book is beautifully written. You bravely write about challenges that most people shy away from. Remember that your mother was just a person, with her own hurts and flaws, and be gracious. Thank you for your honesty and willingness to share vulnerable experiences, which help to heal others.

See how much better that sounds?

Here’s another tip. Having reframed that criticism for myself, I actually feel better. My chest has relaxed and I can breathe deeper. Why is that? Our brains don’t differentiate who says what. If I say something kind to myself, my brain responds the same as if someone else said it to me. My brains tells me someone (in this case, myself) has been kind to me, and I feel good. Conversely, (and this is key) if I say something mean to myself, my brain responds the same as if someone else said it. My brains tells me that someone was mean to me (also myself), and I feel bad. So, by rephrasing the review more positively, even if just in my own head, I remove the sting.

There is a lot of psychology in this piece. To recap:

1) Strive for 5:1 (positivity: negativity) in your relationships.

2) Start conversations, particularly challenging ones, with a heartfelt appreciation.

3) Talk to yourself positively. Your own words count. Speak to yourself as lovingly as you would to your best friend.

4) Remember that we all have a little kid inside us, hoping to be loved and appreciated. Be kind to your own little kid, and be kind to other people’s little kids as well.

Also, like Dylan sang, “Don't criticize what you can't understand.”

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

March 30, 2022

Great Expectations

Guest blog by Dorothy Brush Henry

My family never loved out loud. No one ever sent me off to school, or ended a phone conversation, or tucked me in at night with a deliberate “Love you!”

Indeed, in all of my growing up years, not one single person ever found even one single occasion when it might be warranted to tell me I was loved. So when my mother surprised me with a crocheted white sweater that she had obviously worked on for dozens of stolen hours, or when my father brought home his paycheck after a long hard week, or my paternal grandmother showed up with a tin of homemade chocolate chip cookies, I named these gifts for what I needed. I named them love. I was so disappointed when it turned out that that sweater was really not very pretty, and my father came home grumpy everyday, and my brother ate most of the chocolate chip cookies. I had hoped, expected, really, that love, when I finally found it, would not be fleeting and flimsy, but rather permanent and perfect. These things, these gifts, could not be love. Where else might I look? I went to visit Grandma.

I am older now than I ever could have imagined as a young whippersnapper. Today I am as old as my great grandmother was when, as a child of just 5 or maybe only 4 years old, I first stood beside her velvet chair worn to a color with no name.

In all the years I knew her, Grandma did only four things that I can recall. One was sitting in that chair, or sometimes, if it was summer, sitting out back next to the barn, or, in winter, bundled up sitting outside on the front porch in a wicker rocker. She was a very good sitter.

She also did a bang up job of drying dishes. After every family holiday dinner, the menfolk would retire to the living room, sprawl out on the couches, loosen their belts and pretend to watch whatever ballgame was in season. It was their snores that eventually betrayed them. This while the women and girls carried all the spent dishes to the kitchen and began the job of washing, drying and putting away. We all had our specialties and assigned chores…Grandma did the drying and the humming. Her constant hums made the work go faster and were a lovely way of drowning out the snores drifting in from the living room.

Before I reveal the third thing, it’s important for you to know that I only heard Grandma speak one time. That was during one of those holiday dinners; it was a Thanksgiving. Grandpa had been loading up her plate with turkey and all the usual fixings. When the vegetables began to be passed, he said kindly, “Here, old woman, have some peas.” He was always kind but maybe a bit brusque sometimes.

“If I want some of those damn peas, old man, I’ll take them myself,” Grandma replied. The room went silent. All of the clanging of silverware ceased. All voices hushed. People who were chewing stopped. Those who were drinking sputtered a little. Everyone turned to look at Grandma. Several of the young ones like me and some assorted cousins, had never heard her speak. Not once. Shocked silence, then an eruption of laughter. Even Grandma laughed, but silently. For the next 11 years I never heard her speak again. She died quietly when I was 18 and away at college.

She did, I am told, once have a voice. I don’t know what caused her to stop using it. As she grew older, then older still, Grandma also lost most of her hearing. She decided, or someone decided for her, that she would thenceforth live in that quiet chair beside the dining room window where her world ended just beyond the glass at the sagging white picket fence. No one expected much of Grandma.

As a little girl, I visited her almost every day. It was back in those times when houses were never locked, so I just slipped in the front door and made my way down the long dark hall to the dining room. In the center stood the great oaken table, its clawed feet clutching at a worn floral rug that anchored the room. I helped myself to a Kraft caramel from the old glass candy jar, nodded a greeting to the line of ancient family that paraded across the mantle in their tarnished silver frames, then went to stand beside Grandma’s chair. I unwrapped my caramel and as it melted in my mouth I waited.

I never had to wait more than one full candy-worth before she sensed me there. Suddenly she would become alert to the moment, deserting the memory world where she floated through her days. As she turned toward me a smile would already be transforming her face….eyes, mouth and cheeks. She would mouth a silent “Ohhh!” which I always thought, if it had sound, would be a bit of a cute, rusty little squeak. She stretched out her arms and maybe she pulled me or I fell into her but I know it was both, then we shared a hug that I can still feel to this day. Soft and warm and real. I did not have to guess if this was love. It was a quiet truth. Grandma followed no pattern, punched no time clock, read no recipe. The many people in my life who were perfectly capable of speech, of telling a little girl when she was sad or silly, “I love you,” never did. The one who could not speak told me over and over again. Her hugs were quiet but never silent.

I keep my memories of those days tucked away in quiet drawers, between sleepy journal pages, in the pocket of my winter jacket. Vignettes of long ago people, of incidents and accidents, of touches - gentle or bruising. I take them out sometimes and rerun them like old black and white movies, frame by stuttering frame. And like those very old films, they are silent. There is no soundtrack. Except for in that one. That one where my great grandmother, sitting in her faded chair by the window, turns to me with a smile. And then I can hear it. In her sweet, squeaky whispered, “Ohhh!” I hear it. And I say - out loud, “ I love you too, Grandma…”

Dorothy Brush Henry spent her childhood in a small antique village on Long Island. She earned an undergraduate degree in Sociology from SUNY Binghamton and years later another BA in Gerontology from Molloy College which enabled her career (and her dream) of working as a recreational therapist in assisted living facilities. As the unofficial historian of her family, she has collected and cataloged albums full of documents and photographs. By adding her written memories of family persons and happenings, she hopes to leave a more personal and vibrant story for the generations to come.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.