Lise Deguire's Blog, page 6

October 13, 2021

Why Me? Why Not Me?

(This is Part 3 in the series "Choosing More Surgery." See here for Part 1 and here for Part 2)

“How are you doing today?” asked my nurse.

I instantly burst into tears. I had been holding it together ever since Anthony, the aide, adjusted my pillow. I had come to the burn unit for a post-op visit and laid down on the exam table. “Are you comfortable? You don’t look comfortable,” Anthony asked.

“Not really.” Expertly, he adjusted my pillow three inches down. “Is that better?”

“Yes.” At this moment, my tears began to form. There was something about Anthony’s attunement to my discomfort which kicked me in my incredibly sore stomach. In fact, I had not been comfortable for five weeks, since my first of two major operations to graft my torso. (For more on my surgical issues, see here). I had been soldiering on, trying to ignore my discomfort, which was a 24/7 situation. But the kindness in Anthony’s chestnut brown eyes, his simple concern about any pain in my neck stirred all the tears I had been pushing down. So, when the nurse came in and asked how I was, I wept onto my perfectly placed pillow.

“It’s not a good day.”

“It’s been a really long journey, what you’ve been doing.”

“Yes, so long.”

This was the conversation I had at my recent check up, even though things are actually going well for me. No infection! Grafts taking nicely! Everything is healing! But I am so tired. I hurt. I continue to be uncomfortably bandaged from my chest down past my waist, with a massive new bandage on my right thigh. My constant companion, my wound vac "Walter" has been removed, (Hallelujah!), but I still have four open surgical sites. (For more about Walter, see here). I am, in fact, NEVER comfortable, Anthony’s efforts notwithstanding.

I sleep only with chemical assistance. I limp. I haven’t showered in five weeks.

Look, I am a positive person by nature. I talk to strangers and compliment their shoes. At doctor’s appointments, I always ask the nurse and doctor how they are feeling. I can spot the positive outcome behind any storm of dark clouds. I have spoken about resilience on TV and radio, using my own story as an example of overcoming terrible odds. This is my gig, and this is how I usually roll.

But not today. Today I am sad and tired. Today I might feel sorry for myself if I let myself go there. But that is one dark road I rarely travel.

“Why me?” I wondered recently, in the middle of a lonely, aching night. My open wounds throbbed. I tried to twist slightly in the bed, uncomfortably stuck in the same position. I was hot, I was cold. “Why do I have to be burned? Why must I go through this?”

“STOP!” said my cerebral cortex. “Stop that. It will get you nowhere. It’s the middle of the night. That is not a good thought for you. Just try to go back to sleep.” And so I did. I stopped that thought, the dark snake that would lead me into a treacherous dark jungle, and I went back to sleep.

But as I write today, that thought returned, and all my tears flowed. Why me indeed? I’m a good person (usually). I’m nice (usually). I help people when I can. I’m a good wife, mother, and friend (usually). I even send hand-written thank you notes. Why must I be severely burned, endure endless surgeries, still living the life of a disfigured woman? Why did I have to do this all alone as a little girl, lost in a burn ward with no parents around? My trauma of being injured and forgotten is so intense that even now, newly injured, when people show up for me, I feel astonished to be remembered.

I have carried such pain all my life, endeavoring to do so cheerfully, hoping that others would help me, because I had no one I could count on. And now, 54 years after my initial injury, I have this pain and discomfort all over again.

Why me?

But, you see, I know the answer. Why not me? Life is painful and life is hard. Maybe not all the time, although for some, life is truly painful and hard all the time. I have clean running water. My refrigerator is stocked. I am never afraid for my safety. There are plenty of ways in which my life is not hard at all.

But even among my safe, first-world, well-off compatriots, there is plenty of pain. Dear friends die young from cancer or fall dead while shoveling snow. Sons die suddenly in the middle of the night. Beloved husbands transform into strangers and abandon their families. Children disappoint, sometimes heartbreakingly so. Addictions ravage our savings and alienate our families. We get downsized out of the only job we ever had.

In fact, if we live long enough, we are guaranteed to lose our beauty, lose our physical strength, lose many loved ones, and eventually die. That will happen to all of us if we are lucky and live a long life.

So, why me? My current ordeal is my life’s journey. I don’t know why. Maybe someday when I die I will learn why this was my life's path. Right now all I know is that that everyone, eventually, has their own ordeal. Awareness of this fact raises me out of self-pity into universality. Yes, I am in pain, and yes, it makes me sad. I also know that this is life. Life can be hard.

I also know that this suffering, like my previous bouts, will end. The earth will spin, days will pass, and my wounds will heal. Someday soon I will be out and about, just like before, only breathing deeper and feeling more comfortable. I look forward to that day very much.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

September 29, 2021

I Hate Walter: Choosing more surgery (Part II)

(For Part I of this series, click here)

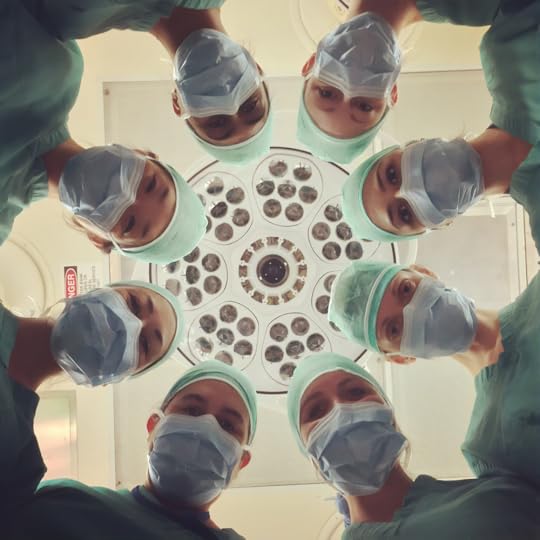

“You need to make friends with it,” advised my surgeon. She smiled at me, her long straight blonde hair pulled into a neat ponytail. She stood in perfect posture, trim in her blue scrubs.

Dr. Eberwein’s appearance was in direct contrast to mine. I peered up at her from a confoundingly uncomfortable hospital bed. My curly hair sprawled over the pillow. I wore a blue and white hospital gown, a “Johnnie” as they are called. Underneath me was a “Chuck,” a plastic backed, soft-topped rectangle used to catch errant liquids which might ooze from my hospitalized body.

I had one IV in each arm, two pumps coming out of two separate wounds, a blood pressure cuff on my left bicep. And, to my doctor’s point, there was a long hose, one end attached to my abdomen, the other end affixed to a large pump.

“You need to make friends with it.”

This “wound vac” was to be my constant companion for the next six weeks. Like Mary’s Little Lamb, everywhere I went, this vac was sure to go. Its hose stretched only 36 inches, tethering me in place like a horse. If I strayed too far, somehow forgetting about my new “friend,” it would tug painfully, pulling on my sizable abdominal bandage.

Picture a large plastic rectangle, affixed right under your breast line with glue, stretching as far as possible around both of your sides. Tug that plastic down below your waist. Fasten it tightly to your skin on all edges. On top, plug in a long plastic tube, and attach it to a portable vacuum. Then, turn the vacuum on. Feel the plastic bandage shrink down tightly to your wounded skin as all the air sucks out. Underneath the tight hot plastic, your wounded skin might give you shoots of pain. More annoyingly, it might itch the kind of itch that could drive you mad.

Wear this bandage 24/7 for six weeks.

There are worse things. In fact, there used to be much worse things. I have been skin grafted so many times I lost count. As a child, this grafting was torture. The pain of the bandage changes would reduce the entire children’s burn unit to howls of pain. Every child shrieked in agony, twice daily, when their bandages were changed. (For more on these early days, check out the award-winning Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor).

That was 50 years ago. Recently, I spent four nights in the hospital for this current surgery. At one point, I turned to my husband and said, “You know what? I haven’t heard a single person scream in pain. Not even once.”

Burn treatment has advanced. New bandage technology has vastly reduced the old torture that I, and so many others, once endured. My nurse advised me that “We aim for the pain level to be zero.” Zero! And indeed, my pain level, while not zero, has been remarkably low. So, listen, I am not complaining.

Although, I am complaining, because of this wound vac situation.

The purpose of the wound vac is to hold my open graft site in place, so that artificial skin can embed, take hold, and “vasculate.” Once the blood vessels have grown in, I will have yet another surgery (bummer!), to cover over the new graft with my own skin. In the meantime, the wound vac covers the site, encourages “vasculation,” and protects the open wound from infection.

“You need to make friends with it.”

Days later, I spontaneously dubbed my wound vac “Walter.” I don’t know how to make friends with something without a name, and Walter was the name that popped into my head. I don’t know why. The only Walter I ever knew was a Walter who attended the college my dad taught at. That Walter was a kind, lovely man and I liked him very much. This Walter sucks. I mean this both literally and figuratively.

“Don’t forget Walter!” warns my daughter when I stand up too fast.

“Walter got stuck,” I complain to my husband, waiting to be untangled.

“Can you plug in Walter?” I ask at bedtime, so that the wound vac can charge overnight.

Walter communicates. I guess he is trying to be friends, in his own way. “Blep..blep…blep,” he intones, when his suction is perfectly adjusted. At other times, he speaks more rapidly, “Bleppety bleppety bleppety,” letting me know that he is striving to maintain the necessary pressure.

“BEEP BEEP BEEP!” Walter shrieks in the middle of the night. I hoist myself up shakily, getting down on my knees to diagnose the problem. “Battery critically low” is the error message across the wound vac’s display. I thought I plugged him in, but I didn’t.

I hate Walter.

Walter embarrasses me. It is just weird to have a tube poking out the bottom of my shirt, drooping along the floor, and ending in the black messenger bag that hangs on my right shoulder. “Blep… blep… blep,” he drones on, in his endless loop.

Except it is worse than that. Every three minutes or so, Walter takes a quick breather. “Blep… blep…blep…. (silence)… PWPWUUUUT!” That final bit sounds exactly like an explosive fart. My family laughed at that in the beginning. We joked that Walter provided the perfect cover for a person who needed to pass gas. It was funny for about 20 minutes.

It has been 21 days.

“Blep…blep… blep… (silence)… PWPWUUUUT!”

I am glad that burn care has advanced. I am grateful to be in minimal pain, and look forward to my grafting being complete. Already I know it will be worth it.

“Can you take a deep breath?” my surgeon inquired, one day after the operation.

In my bed, I inhaled. Holy cow, it was true! My abdomen expanded and expanded. I had no idea that lungs could fill so deeply. It turned out that I hadn’t taken a full breath in… 40 years? So, even though my middle is still a vast open wound, I can tell that I will be much more comfortable inside the new grafts. The tight pressure that has been my constant companion, the permanent corset that limited my breathing and caused pain after any big meal, that corset is gone. I am going to be so happy.

Once I get rid of Walter.

“Blep… blep… blep… (silence)… PWPWUUUUT!”

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

September 22, 2021

Staying Alive: Lessons from my Brother's Suicide

(Re-released today, in memory of my brother, and in honor of National Suicide Prevention Month.)

Chances are, you never met my brother. There are still some people around who did, friends from high school, friends from college. Even now, 40 years later, friends of Marc’s contact me.

“He was the smartest person I ever knew.”

“He was my best friend.”

“People tell me I’m a genius, but I tell them they should have met Marc Deguire.”

I think Marc was destined to become a college professor. He was a masterful, if amateur, teacher. He patiently explained algebra to me when my math teacher failed. At the age of 16, he instructed his older cousin how to drive stick-shift. He attempted to teach our father how to pitch the family tent, but that was hopeless. My father couldn’t learn those kinds of things, but it surely wasn’t my brother’s fault. Marc should have graduated M.I.T., earned his doctorate in physics, and taught at a small liberal arts college. He could have inspired his students, coaching, advising, coaxing along, just like he did for me, his little sister. I can see him now, wearing a corduroy jacket, wire-framed glasses and a big wide smile.

But that is not what happened. What happened instead was that my brother, Marc-Emile Deguire, hurled himself out of the 16th story on the MIT campus, and plunged to his death. He was 19 years old.

My brother’s death is the single worst thing that ever happened to me. Now, as a psychologist, I spend far too many hours coaxing my precious clients back from the abyss of hopelessness and despair.

If you are feeling suicidal, I understand. Many people struggle to go on living at times; the feeling is not as unusual as we might pretend. Life is hard, much harder than we tend to admit to others. It is not uncommon to think that death could be a relief, in our darkest moments.

But hear me please; hear me loud and clear. Suicide is a terrible legacy for those you leave behind. I know this as a suicide survivor, and also as a clinical psychologist. The people who love you do not recover from a suicide. Sure, they go on. Sure, they will feel happiness again. But the legacy of suicide is devastating. It is the awareness that the person chose to leave you that is hard to get past. Sometimes people feel that the suicidal person didn’t love them enough to keep trying. Sometimes they feel the person didn’t care enough to stay alive. Sometimes they feel horribly guilty for not saving the person. They wonder, forever, what they should have done differently. These thoughts and feelings don’t go away. The thoughts stay, firmly encamped.

Miraculously, some people survive jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge. These people intended to kill themselves but wound up not dying. When they survived, unexpectedly, each one stated they felt joy to be alive and that they regretted jumping the instant their feet left the bridge. What were the thoughts of the jumpers who didn’t survive, as they plummeted toward the water. Did they also regret their choice?

Did my brother?

These are thoughts I bear in mind when working with clients. Misery can feel unbearable but it is not permanent. Excruciating moments can be survived. I offer hope that everything changes, awareness that misery is but a moment in time. I inform clients, again and again, that the legacy of their suicide will be a dark burden for their friends, family, and most importantly, their children. If worse comes to worse, I arrange hospitalization for clients, where they can be kept safe and secure until their despair lifts. And in the end, clients are always grateful they stayed alive. Misery passes, if you can hold on long enough. Everything passes, in time.

My brother didn’t have a therapist to guide him away from his plans. He didn’t have medication. He didn’t have a support group. He didn’t have a lot of things that he needed. I think he left me here with a job to do, and lessons to keep sending out:

1) Live your life. If the only thing you can do today is eat a little and brush your teeth, OK. Get some help. Keep going. We need you. It is not your time to go.

2) Never believe the thought “People will be better off without me.” That thought is a symptom of your despair. It is not an accurate thought. It is a symptom, like having a fever is a symptom of infection. Even if you are having a very hard time, no one will be relieved by your death. Really.

3) It is easy to give you hotline information (and here it is: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/chat/). It is not as easy to climb out of a deep, dark hole. I recommend finding an excellent therapist and considering medication. I suggest daily exercise and getting outdoors. Learning meditation can be a lifesaver. Please call the friends and family who love you and let them know that you are struggling. There are many paths back to health. I have walked with a lot of clients on these paths, and I know that it is possible. You can feel hopeless one month and be full of joy the next. Truly.

When I was 12, I was complaining to my brother one day. He was 17 at the time.

“You’re so… special. I’m not. You’re this genius, everyone talks about you all the time and I’m like…nothing. All I am is… nice.”

My brother Marc looked at me very intently. There was a moment’s pause. His brown eyes shone with light and care. Gently, he replied, “But Lise, being nice is the most important thing of all.”

I don’t know what is the most important thing of all. I do know that it is important to stay alive. Breathe in, breathe out. Death will come eventually, and we will all figure out what happens then. In the meantime, please take care of yourself, and try to take care of the people around you. If you need help, get help.

Be like my brother in your compassion and your wisdom.

Be like my brother in your depth of knowledge and sincerity of character.

Be like my brother in your passionate love of family and friends.

But be like me in staying alive.

#resilience #mentalhealth #suicide #psychology

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

September 15, 2021

Books that Heal

When I was 28 years old, I briefly dated a surgical resident. Perhaps like all surgeons, he was smart, decisive, and pleased with himself. I thought we were going somewhere. But after a few weeks, he suddenly dumped me, refusing to explain why.

I felt heartbroken, even though the relationship was new and, truth be told, I had liked others more than him. (Remember that “pleased with himself” part?) But being 28, single and a burn survivor, my chances at finding love seemed increasingly remote.

That week, I showed up for my psychology supervision, barely holding myself together. My clinical supervisor, a kind man named Byron, asked me what was happening. I told him my tale, weeping, while he listened attentively.

“I hear you. Breakups are so hard. Listen, I want you to buy this book. It’s called How to Survive the Loss of a Love. It will help.”

I went immediately to the bookstore and bought the book, feeling dubious that it could sooth my despair. But it did. The book, by Bloomfield, Cogrove and McWilliams, was full of brief chapters, short enough that a grief-stricken reader like me could make my way through, such as:

“YOU WILL SURVIVE

· You will get better.

· No doubt about it.

· The healing process has a beginning, a middle and an end.

· Keep in mind, at the beginning, that there is an end. It’s not that far off. You will heal.

· Nature is on your side, and nature is a powerful ally.

· Tell yourself, often, ‘I am alive. I will survive.’

· You are alive.

· You will survive.”

Since that breakup, 30 years ago, I have frequently recommended this little book to others who are grieving. I sent it to my own daughter when she suffered a painful loss. She read it too, taking it on the subway, bringing it to picnics, feeling its comfort.

Then there was The Year of Magical Thinking. Joan Didion wrote this heart-searing memoir of her sudden death of her husband. This book captured the crush of grief, the shock of loss, the thinking that can verge toward psychosis. In Didion’s words:

“This is my attempt to make sense of the period that followed, weeks and then months that cut loose any fixed idea I had ever had about death, about illness, about probability and luck, about good fortune and bad, about marriage and children and memory, about grief, about the ways in which people do and do not deal with the fact that life ends, about the shallowness of sanity, about life itself.”

Didion’s book articulates the experience of grief with grit and depth, more truly than any book I have read before or since.

When I work with widows, I often recommend Didion's book. “Be warned, this is not a feel-good book. But it will help you feel less alone. It will put words to the deep pain you are feeling.”

Often the next session, the widow comes back into my office, smiling a bit and shaking her head. “That book… that book. That’s exactly how it is.”

Good writers capture the experience of living, the depth of our pain and joy. They verbalize our moments of anguish, and articulate our silent experiences. Good writers connect us with humanity, even when we feel profoundly alone.

When I wrote my memoir, Flashback Girl, I hoped that my words could reach others who suffer. My book is about burns, disfigurement, parental dysfunction, suicide, bullying… My book is also about love, hope, recovery, and resilience. I wrote it for myself. I wrote it for the world. (I know that sounds grandiose and I’m sorry, but honestly that’s the truth). I hoped to reach as many readers as possible to say, yes, life can devastate us, but we can recover too.

Keep going. Have hope. Look for the light.

My hope for Flashback Girl is that it can serve a similar purpose to How to Survive the Loss of a Love, or The Year of Magical Thinking. Perhaps it will be a book that people read when they are in pain. Or perhaps it can be the book that others give to those who suffer, the way I sent How to Survive to my daughter.

Maybe a sad person, grieving a loss, might open their door to find an unexpected package at their entryway. Opening it, a bright yellow book seems to fly out, with a flower on the front. But look, the flower stem is made of a burnt matchstick. And look, the book is about surviving and resilience. The sad person opens the book and begins to read about a little girl who survived a horrific series of events, who now lives a beautiful life.

Hope. Love. Light.

Flashback Girl has been out for one year today. It has already traveled around the world, to readers from Canada, England, Romania, Tanzania, New Zealand, and Australia. I know this because I have heard from readers in every one of these countries. I received emails from people who told me that the book got them through their two year old burned child’s intensive care.

Or helped them decide to be a psychologist.

Or helped them (finally!) understand their mother’s destructive narcissism.

Or helped them resolve to stay alive and not kill themselves.

The book is its own entity now and no longer mine. This reminds me of having babies. My daughters both started as cells inside my body. They grew there, living on my breath and my meals. I gave birth to them and cared for them tenderly. But at some point, those little babies became their own people. They grew up, gained their own character and purpose, and left to fulfill their own destiny.

That is what it feels like to have written this book. It came through me. I nurtured it, I birthed it, I cared for it. I nurture it still, but now it has its own entity, separate from me. My great hope is that Flashback Girl will be a healer in the world, having a place on people’s shelves next to How to Survive the Loss of a Love and The Year of Magical Thinking. That would be an honor. Yes, it’s a big dream, but I have learned to shoot big.

Today is my third baby's birthday. Happy birthday, Flashback Girl.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader

References:

Bloomfield, H, Colgrove, M and McWilliams, P: How to Survive the Loss of a Love. Algonac: Mary Books/Prelude Press, 1976.

Didion, J. The Year of Magical Thinking. New York: Knopf, 2005.

August 31, 2021

Resilience Gained in Dealing with Rejection

Guest blog by Kate Olsen, CHt

I had the pleasure of meeting Kate Olsen when she interviewed me for her radio show, Soul Fire Wisdom. If you would like to listen to our engaging discussion, here is the link: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/finding-resilience/id1482864740?i=1000529520595. For now, here is Kate!:

We have all confronted rejection and still it is one of the hardest and most commonly traumatizing experiences we go through. Most of us learn to deal with it, but some never do and the results can be quite devastating. A client recently told me about a family members’ inability to deal with the trauma and subsequent suicide after feeling excluded. This is an extreme and heart-breaking outcome, but I am guessing there are very few people who cannot relate to the emotional pain that rejection and exclusion can cause. Acceptance and validation are basic to our needs and few of us get enough of these to build our self-worth, self-love and resilience to a level of confidence where we are truly secure and rejection-proof. At least, we seldom get it in childhood and without a lot of introspection, awareness and self-esteem-building work.

It seems to be the nature of humans to try to build their own self-worth at the expense of others when they don’t know more healthy ways of doing so. From childhood into adulthood, we see it. Two friends make themselves feel superior by talking about what they see as the shortcoming of someone else. Many times, we don’t think this is a big deal until we are on the receiving side. The people that are bonding and feeling superior, often lack empathy for the person they are diminishing. That is sometimes because they do not really know the person and sometimes because they do and want to purposefully exclude or diminish them for their own benefit.

I am going to share a story from my own childhood that had a huge impact on me. While today I consider it a blessing, it was difficult then. I was always a fairly kind and inclusive child with a strong sense of fairness, so excluding others or making them feel bad was never something I did. In fourth grade, a classmate had a bird that she brought to school and that bird became the class pet. She was very attached to her bird. She shared the bird with the class though and allowed others to care for it. Over one weekend, something happened and the bird died. The whole class mourned the loss, but it was really hard on the owner of the bird. I had empathy and felt very sad for her. I had an idea of getting her another bird. I organized a group of her other friends and we all planned together to raise the money, get the bird and give it to her. I thought everything was going quite well and was excited that we were going to able to do this as a group.

I had no idea that there were any problems brewing. One day, just a few days before we were going to give the bird to our mutual friend, one of girls asked me to meet her down on the baseball field after school. I didn’t really think much about it and went to meet her and saw that the rest of our group was also there. Still, I thought nothing of it. I had never been bullied or had enemies for the most part, so nothing occurred to me. Suddenly, the group formed a circle around me and skipped in a circular motion while chanting “we vote you out!”

I was taken completely off guard and it took a few minutes to even figure out what they were doing and what it meant. And then, one of them explained that they were excluding me from the group. I would not be allowed to participate in the plans for giving the bird to our friend. My stomach felt like it dropped to my feet and I simply couldn’t speak. I was hurt more than I could have expressed and no words would come out of my mouth. I looked at them trying not to let myself cry and then I walked away as fast as I could. When I got out of their sight, I ran all the way home before I cried. The feeling was horrific and I had no idea why they had done this. I did not know how to deal with the feelings.

I had a hard time going to school the next day and really couldn’t look at any of the girls. It hurt that my friend did not know that her new bird had been from me, as well as, the other girls and that it had been my idea, but I didn’t say anything. It seemed like months, but it was really only days, when some of the girls in the group started coming and apologizing and telling me that one of the girls had instigated what had happened telling the rest them that I was too bossy and didn’t deserve to be in the group. She was jealous and wanted to be in charge of things.

Eventually, all the girls except the instigator apologized and even the girl who got the bird told me she had been told it had been my idea. That helped, but the feelings and mistrust hung on. I avoided the girl who instigated things for the rest of the time we were in school together. I am not sure if she knew that I knew about what she had done. She still talked to me and acted friendly from time to time. I had not realized how insecure and insincere she apparently was, but of course, I knew I couldn’t trust her. I did forgive her. I never wanted to experience anything like that again, however it strangely made me stronger.

It would be decades, more experiences and much self-reflection and self-acceptance before I would feel healed and truly put it behind me. It was the start of a very important lesson on dealing with rejection and exclusion. A lesson I am very thankful for, despite the pain involved. I also gained a sort of “Spidey-Sense” for picking up the energy of people who, due to their own needs, would be inclined to throw me under the bus. I have learned to opt out or avoid them, without malice. I have come to realize that they are doing the best they can with what they know.

I did encounter the instigator of that trauma again on a break after my first year of college. I went into a local store on a visit home, when I heard a voice excitedly call my name and turned around to see the girl who had caused me that pain, with a big smile on her face. She grabbed and hugged me, saying how happy she was to see me. I was in momentary shock. She had surprisingly gained a good 40 pounds and looked a bit different. We talked and caught up on what we had been doing since high school. I was surprised to find out that she was on a break from college and working full-time at the store. She had dropped out of school during freshman year after having an emotional break-down.

I listened to her story and empathized as she told me of her feelings of not fitting in, being excluded and having trouble keeping up academically. She seemed to feel better as I empathized. I asked her about her future plans and encouraged her, reminding her of the skills and abilities I knew she had. There was that moment where I felt a twinge of revenge brewing, but opted for compassion. She went back to school in the fall to a Mid-West college, where she still lives. She graduated, married and has a beautiful family. I wondered if she ever thought about her actions, but realized it really didn’t matter, as I wouldn’t have changed a thing. I was happy I had chosen to react with compassion and knew it was the better choice.

There are many types of rejection that bombard us throughout life. We do need to feel and process those emotions, no matter how painful. In the end, I took the lessons and moved forward, a little bruised, but stronger and wiser. The gifts far outweighed the rest. Use the lessons to buoy you up, rather than make you bitter. Rise above the negativity and know that only you can define who you are and what you deserve.

Kate Olson, CHt, is a Hypnotherapist, NLP Practitioner & Trainer, Reiki Master, Life Coach, Author, Speaker and Radio/Podcast Host of Soul Fire Wisdom. She calls herself a “Change Adventure Navigator”, because she loves guiding clients through obstacles and adversity to find their path, purpose and peace. www.soulfirewisdom.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader

August 13, 2021

You're Never Too Old to Have a Happy Childhood

When I trained to be a marriage therapist, I learned that “you’re never too old to have a happy childhood.” My teacher, the brilliant Maya Kollman, explained that our childhood wounds can be healed by our partners. How does this happen?

Parents are imperfect people, no matter how hard we try, and no one can meet all their children’s needs all the time. We may be exhausted, anxious, or grieving, and temporarily unable to connect with our children the way they need. Still, many parents are “good enough,” in the wise words of psychoanalyst David Winicott. Their children grow up securely attached and they often chose healthy people to marry.

Others, many others, face obstacles. Our parents may have significant limitations, leaving us with unmet needs for safety, approval, or attention. Still, marriage remains an opportunity for a "do-over." Here is our chance to build the kind of family that we never had. For example, if we had a violent father, we can marry a gentle man, giving us the love we longed for and healing our childhood pain.

Of course, reality is more complicated than that. Instead of a healthy partner, we are often unconsciously drawn to partners who are eerily similar to our parents. We don't intend to, but we wind up marrying people who hurt us in the exact same way that our parents hurt us. Think of people you know who were abused as children, who then married abusive partners. Or your friend who had an alcohol father, and then married an alcoholic. We have an unconscious pull toward repetition, in the childhood hope that this time we will finally get the love we want. This pull is mighty, like Jupiter’s gravitational force, unless we work hard to heal ourselves. (For more, read Getting the Love You Want, by Harville Hendrix.)

I have indeed worked hard to heal myself. I have had seven therapists and have tried all kinds of therapy. And I guess I have gotten somewhere because something deeply healing just happened to me. But first, some background…

***

When I was four years old, I stood beside my mother as she tried to light a barbecue. Mistakenly, she poured a household solvent onto the charcoal briquets, thinking it was lighter fluid. (How did she make that mistake? I’m not sure. It was the first night of vacation and it was indeed cocktail hour. So who knows?) At any rate, my mother attempted to light the coals, but they did not light. My mother then poured more “lighter fluid” onto the coals. The coals erupted in a ball of flame, instantly enveloping us, trapping us in a corner of the porch fence.

Frantically, my mother, always a quick study, spied her escape. She dashed through the wall of flame into the nearby lake. But she forgot something. Or rather, she forgot someone. My mother left me, her aflame four-year-old, even though I stood right next to her. Facing death, my mother fled. Abandoned, I burned, my skin melting away. (For more on this story, please see my book, Flashback Girl.)

Although I have no conscious memory of these moments, they fester in my gut and my brain specializes in every possible disaster. Hiking down a dry riverbed, I envision the flash flood, sweeping me away. I imagine automotive crashes, seeing cars slamming into my lane, or the 18 wheeler in front of me suddenly stopping. Fireworks set my spine on edge.

(I recently attended a bridal shower, in which the cake was topped with a beautiful sparkler, shooting out tiny flames everywhere. “Who doesn’t love a sparkler!” exclaimed one of the guests.

“Me,” I murmured.)

I spy danger all around, assuming I am on my own and that no one will help. Raising two little girls drove me a bit crazy. Holding their tiny hands in a parking lot, I saw them being hit by the cars backing up. Bath time was a repeated risk for their blonde heads to slide underwater. It took all my willpower not to be an over-protective mother, restraining them from free play. “Yes, go swing on the monkey bars!” I would chirp, forcing myself to smile.

Julia and Anna would scamper off, while I imagined their crushed skulls and tiny snapped necks.

Perhaps all mothers sense danger around their kids. Perhaps we all live in fear. I think I carry it a bit too far, even now that my daughters are grown. Maybe I counterbalance my mother, who never saw the dangers for her children. But, my brother died, my stepsister died, and I almost died too. So maybe I see all the dangers that my mother couldn’t see, parading in front of me, waving their bright red flags.

“Careless driving!”

“Walking alone in the city at night!”

“Failure to complete the antibiotic course!”

Danger, danger, danger!

***

One recent morning, I awoke, pet my dog, and walked into the kitchen to make my coffee. The following details matter here, so bear with me.

To make our coffee, we use a pour-over drip filter. It takes more work to make the coffee by hand, but the strong aromatic brew is its own reward. The black plastic cone sits atop a coffee mug, full of grounds. Then, we use boiling water from our tea kettle, pouring the steaming water into the filter, where it drips into the mug.

My husband Doug came downstairs, and we were talking. I stood in front of the counter, brewing my coffee. Doug needed a plate from the kitchen cabinet, and I stood in his way. So, he came up behind me, and reached his long right arm around me to get into the cupboard.

Doug couldn’t see the pour-over filter in front of me, brimming with steaming water. He brushed against it, and the filter crashed. The steaming water sprayed everywhere, on the counter, on the floor, but most alarmingly, all over me.

Instantly my pajama pants were drenched with scalding water. My right sock was also soaked. Unbearable heat swarmed me.

It would be satisfying to be able to tell you what I remembered in this moment. Perhaps I could say I had a flashback to the original fire itself. Perhaps I could see my mother dashing away. Perhaps all my memories might come flooding back in a sudden torrent, bursting through the dam of 54 years of repression.

But none of these things happened. It was a blink of an eye; a blank moment in time.

“Owwww! Doug!”

Instantly, Doug lifted me away from the counter, twisting my body away from the spill. He was hurt too, but not badly.

I ripped off my pajama bottoms and my sock. “Ow!!”

We stared at each other, aghast.

“Are you all right?”

“My foot is scalded. Thank God those pajama pants weren’t tight-fitting, and I stripped them off right away.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t see the filter.”

“It’s OK, I’m all right.”

I went upstairs to get changed while Doug cleaned up the kitchen. Coffee grounds had sprayed everywhere, like a monochromatic Jackson Pollock painting. “Put your foot in cold water,” he suggested.

I stood like a flamingo, with my right food in the bathroom sink. I examined the skin. It was red but not bad. No blisters. No blackness. Just a mild burn.

Then, still in my flamingo pose, it hit me. Here I was again, burned unintentionally by a family member. But this time, it was so different; my husband’s instinct was to protect me. He had been hurt too. But then what did he do? Did he leave me? Did he protect himself? No. In the panicked moment, his instinct was to grab me and to keep me safe.

Something inside me feels more settled now. Something inside me feels healed, a bit. So, was that marital theory right? Is my childhood history of abandonment and trauma now healed? Did my husband, in one heroic moment, reverse all the damage done as a child? Am I finally going to have that happy childhood?

Well, I still have my history, and I still have my fears. Fireworks still come too close for comfort. Cars still veer toward me.

But it helped. It really helped.

Lise Deguire's multiple award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

July 30, 2021

Abandonment and Resilience

By Dr. Michael Lennox

This beautiful piece was written by my very first best friend in the whole wide world. Michael and I became dear friends in first grade and we are close to this day. Here is a guest video we recently filmed together. If you watch, you can see the great love between us still: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uomkibg1A88&t=28s. Here is Michael!

I know a lot about the wound of abandonment. One of the dictionary definitions of abandon is “to withdraw from; often in the face of danger or encroachment.” When I was younger in my adult life actively working through my childhood wounds, I often used this notion to describe my relationship with my mother; that she abandoned her children. And yet, this wasn’t exactly what happened. My mother didn’t withdraw from us in the face of danger, it was she that was the one creating the danger. And she didn’t leave us, but carried us with her into and through her chaotic approach to life. And of course, on the other side of healing all those wounds of abandonment, I have a very different perspective on what abandonment is, what it isn’t, and what the gifts were of having the mother I had.

The story begins with the three of us being raised by a single mother, living at the poverty level, who was working full time while also going to college. This is not a tale about the resilience of my mother, though she was indeed wildly resilient in her own right. My mother was traumatizing to all three of her children; a woman with a personality disorder, clinical levels of ADHD whose executive functioning was profoundly challenged, and we three latch-key kids were truly left to fend for ourselves from a very young age. And fend we did.

Life at home was chaotic, violent, unpredictable, and felt profoundly unsafe, and at times that feeling of unsafety was quite literal. But out in the world, I moved about with a kind of ease and confidence knowing that my older sister and brother had my back. We took care of ourselves and each other, and while we reflected the chaos and instability of both of our parents in how we tore the place up everywhere we went, we were intellectually smart, emotionally intelligent, and capable of navigating our way in the big bad world; at least outside of the house this was true.

One of those outside of the house experiences was summers at the New Jersey Y Camps, where we went under full scholarship from the Jewish community. We were wildly popular at camp; our sibling unit was even known colloquially as “the Lenusky’s” (I later changed my name to Lennox). My brother David was the bad boy that all the girls had crushes on. Kathy, my sister, was a powerhouse, remembered decades later as not only popular, but a natural leader who generated a tremendous sense of social respect. I had already been bitten by the stage bug in grade school, and this summer camp had a really strong drama program led by a charismatic high school music teacher who made the summer musicals the most coveted activity. If you had leads in the plays as I did each summer, you enjoyed an elevated social status. While this is hard to convey, trust me when I tell you that the visibility and popularity that the three of us moved through in that community was extreme, and truly unusual.

With the unexpected passing of my brother seven years ago, and then more recently my mother, Kathy and I have been moved to a lot of reminiscing, seeking to contextualize the past. It was she that proffered the answer to the mystery I always found our wildly popular summer experience to be. She reminded me of the construct of the social dynamic of this community. Upper middle class, well-educated families of means, these children were protected to the point of overprotection, cared for and well nurtured, and for the most part, these were kids who had things done for them at every turn.

We, on the other hand, were not protected. The care we received was unstable at best, and if we had needs, we were forced to learn how to meet those needs, for some of them otherwise would not get met with consistency. We took care of ourselves, and if something needed to get done, we had the smarts and energetic resources to get it done. It was our capacity to problem solve and rally our own resources that was what lifted us up in the eyes of this community. Sure, the personal charisma that we all had certainly helped, but it was our capacity for executive functioning, and for what I would later learn was something called resilience that made us the unicorns of Cedar Lake Camp in the 1970s.

There were traumas to heal by virtue of being the son of my mother, more than most, not as much as many I have met. Every single wound, and the movement through those wounds as an adult, have led to amazing results. It is true that my mother was barely around in those formative years, and when she was around, it was more likely than not that her stress level would erupt into violent rage. And when I needed her the most, she was not there, and in writing this I am reminded of the painful awfulness of how she responded to my coming out as gay when I was fifteen. It is fair to say that if there were one word, one wound that my mother’s behavior caused her to inflict on her children, the word that fits best, is indeed abandonment.

Today I can see that the experience of abandonment and resilience are directly connected. I have also come to understand that there is a distinction between being abandoned, and feeling abandoned. We were indeed left to our own devices more than was often safe. But it was this very perceived abandonment that generated so many skills and efficiencies with how we all move through the world. So, were we really abandoned? One answer is certainly, no, we were not. As unsafe as my mother was, she was still a powerful force of nature who would have – and did – protect her children as a fierce lioness might. But did we feel abandoned, yes, and at every turn. Feeling abandoned left me with a wound to heal. Being abandoned left me to fend for myself offered practical experience that helped me generate life skills, and a foundation of resilience that would serve me well in my adult life.

About Dr. Michael Lennox: Psychologist, Astrologer and Dream Expert, Dr. Michael Lennox has been helping people have a deeper understanding of their unconscious mind for almost twenty-five years. In workshops, in the media, for private clientele and on the internet via his popular website www.michaellennox.com , Lennox guides people through life’s mysteries with a deep and profound wisdom delivered through a humorous and extemporaneous style that has become his trademark. He is your ambassador to conscious embodiment. His #redrobeastrology reports on Instagram are growing in popularity with every passing month, reaching thousands of people every day.

A highly sought-after media expert, Dr. Lennox has been seen internationally on many television shows, beginning with the Sci Fi Network’s The Dream Team with Annabelle and Michael, in January 2003. His radio and podcast appearances talking about the power of dreams and the impact of astrology now number in the hundreds. Lennox obtained his Masters and Doctorate in Psychology from The Chicago School.

Lise Deguire's gold award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

July 9, 2021

Choosing More Surgery (Option 2)

“Your test results were negative.”

This call was welcome news from my doctor, but also surprising. I had seen Dr. Jones (not his real name) for countless years, and he had never telephoned to announce a negative result. I did not yet realize these words would be the only good part of the call.

“I talked with the radiologist about your implants.” (Sorry about the T.M.I. but yes, I have implants. As a childhood burn survivor, implants were necessary.) “The radiologist says you have an intracapsular leak. That means they could leak inside your body, which isn’t good. They should be removed.”

Dr. Jones hesitated. “We will need a special surgeon, because of your torso.”

Yeah, no kidding.

My torso remains the same size as it was when I was four and burned in a horrific fire on two-thirds of my body. I am burned almost everywhere, but my torso is the worst. I am deeply scarred around my waist, my middle, and my chest. The underlying fat and musculature were also partly eviscerated. The skin there is as tight as a drum. My skin has not expanded for the past five decades. If you pushed your finger against my chest, the tight skin would not budge an inch in any direction.

I suddenly envisioned being cut open during surgery to remove the implants. I saw my innards springing out from my body, like confetti, joyful to be released from 54 years of bondage inside the tight torso.

“I do have a burn surgeon. She can do the procedure.”

“Oh great.” I could hear the relief in Dr. Jones’s voice. “I will talk to her, and we will get this going.”

“Thank you. Thank you for taking good care of me, even though I’m so complicated.”

“Of course, Lise. Of course.”

Lucky for me, I guess, I was already scheduled to see my burn plastic surgeon for a laser procedure in a few days. Lucky in that I have an extraordinary plastic surgeon who provides me with world class burn care.

Unlucky, in that I have to do any burn care at all.

This tight torso is not a new problem. In fact, the constriction has plagued me for over 30 years. Two surgeons have explained that I could feel more comfortable. Possibly my skin could feel less banded, clutching me like a permanent girdle. Possibly my four-year-old torso could be brought into better balance with my middle-aged hips. What I need is massive skin grafting. (For a longer explanation on skin grafting, burn care and my story, I cheerfully refer you to my book, Flashback Girl).

A surgeon once told me that he could use the extra stomach skin that arrived unordered when I birthed two perfect babies and flap up that unwanted skin where I need it most. Now doesn’t that sound perfect? What woman would put that surgery off for 30 years?

A traumatized woman.

Also, a self-employed psychologist with a full private practice and no paid sick time.

***

A week later, I sat in the burn center, Michelle, the whole-hearted burn nurse nearby. Arms outstretched, I held my blue hospital gown wide open, feeling like a flasher. My esteemed surgeon, Dr. Eberwein, assessed me keenly, eying my waist and middle. I watched her and waited while she looked at my scars. Dr. Eberwein explained that there were three possible options.

1) Option 1: remove and replace the implants. This would solve the leakage issue, but not the tight torso issue. One surgery.

2) Option 2: Remove and replace the implants and do the dreaded skin grafting. This would bring me the relief for my tight skin. Two or three operations, each requiring a 3–5 day hospitalization.

3) Option 3: Option 2, plus have a number of other surgeries to reconstruct more normal skin over the whole area (“the DIEP”). Dr. E seemed most intrigued with this option.

“You would have to have it with another surgeon; I don’t do the DIEP procedure. But then I would do the grafting afterwards. The results could be very good.”

“I would have to be in another hospital?”

“Yes, and there would be multiple major surgeries, plus what we would do here afterwards.”

“I don’t think I want that.”

“Yes, but look it up before you decide. It is cutting edge and they are getting great results.”

“I will. But if I just do the grafting, I will be here with you. On the burn unit. Right? I will be with the burn team here?” My vocal tone rose, and I sounded increasingly like the child I felt inside, the four-year-old inner me that perfectly matched my four-year-old torso.

“Yes.” Dr Eberwein and Nurse Michelle looked at me kindly. Their eyes shone with care. They knew why I asked.

***

No one understands being burned unless you have been burned or lived in the hospital trenches with someone who has. The pain, the vulnerability. Being skinless. Depending on strangers to help you. The fear. The sadness. All of this reverberates inside me still. Medical procedures are triggering so I have no interest in being at a hospital with a surgical team who doesn’t understand. But at Lehigh Valley Burn Center, I don’t have to explain a thing. They know. I can relax there, safe with a staff that truly cares about trauma.

After my consultation with Dr. Eberwein, I had my 16th (??) laser. Those aren’t a walk in the park either, let me tell you. They did give me a little down time though. So, during my days of recovery, I had time to contemplate my decision.

I talked to my husband. I talked to my daughters. I talked to friends. There was no one, I repeat no one, who thought it was a good idea for me to do Option 3. I am a married woman in my late 50s. If I were 18, I would have made a different choice. If I were 18, I would be desperate for The DIEP. But I am not 18, and every surgery rocks me to my core.

Plus, I have clients and a practice, and people who depend on me. It is one thing to have 2-3 surgeries and quite another to have 5-6.

Option 2 it is. I realize too that there is no time like the present. Here is a grateful list of what I have going for me, right now, which may not always be the case.

1) Dr. Eberwein, whom I trust 100%.

2) The burn team at Lehigh Valley, whom I also trust 100%.

3) Good health insurance.

4) Good health.

5) I’m not getting any younger.

6) The ability to see my clients via teletherapy. I always thought I couldn’t take off much time from work for surgery, because of my caseload. People depend on me and I am devoted to them. Now, even if I am stuck at home and unable to do much, I can still see my clients, just like I did all through the pandemic. Teletherapy will make these surgeries possible.

So, Option 2 will happen in September, continuing for 8 weeks. I will be in and out of the hospital or recovering at home. I have been in the hospital countless times. That part won’t be new. This time, however, I will go to surgery as a writer, and report back to you from the hidden world of burn care. I hope that my journey can help inform other burned folks and the people who love them. I hope that my writing will capture this strange world of scars and skin, grafting and donor sites, pain and recovery.

I also hope to have softer, plentiful skin around my middle. At long last, I hope to be comfortable.

Lise Deguire's gold award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

June 18, 2021

Re-silly-ence

by Marc Kaye

I asked myself, “Self, are you resilient?" I heard a voice. He sounded a bit like Kevin Hart. He said, "Hell, ya! You raised two teenagers, didn't you? And don't forget about that whole adolescence thing you went through yourself." So, I guess you could say I am somewhere in the resiliency neighborhood.

When Lise asked if I would write a blog about this topic, I was honored. Then, I was panicked. I thought, "Well, am I really resilient?" To be fair, I was brought up to keep moving on no matter what happened. My family wasn’t the type to really talk about our feelings, but my sister and I got the memo - just keep moving forward.

Even the night my mother died; she was sending me a reminder from the great beyond. After eating takeout with my dad, sister and aunt and uncle, we cracked open our fortune cookies. "Never give up", mine commanded. Really? Can a guy catch a break and meltdown once in a while? My mom had to get the last word in, even then. Now that's never giving up.

I wouldn't characterize myself as a super strong guy, physically, or emotionally. I work on it, but both my physical and emotional resiliency workouts are very similar. I'm gung-ho until I am suddenly in search of a convenient distraction from what is uncomfortable. Sometimes it's an overstay in my bed. Sometimes it's Netflix. Sometimes it's a full-size family pack of strawberry Twizzlers. Occasionally, it's all three, at the same time.

So, to be honest, I consulted Merriam-Webster. There, resilience is defined as "the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; toughness." That's when I started to doubt myself. I recover from difficulties but quickly? Let's just say I'm still getting over being picked last for kickball in 4th grade. To put it into context, I am the slow cooker crock-pot version of how one goes about processing feelings. In contrast, I think everyone in my family is the microwave variation. This probably explains a lot.

Maybe I’m just "resilient-curious". I've heard about it. I know people who have it. It's something I've been thinking about. Maybe I’ll try it one day.

The one thing I am is funny. Or so I've been told. Let’s just say I’m “re-silly-ence” and leave it there. As a stand-up comedian and a writer, much of the humor comes from dealing with rejection and discomfort and, in general, trying to understand my place in the world. It's painful sometimes. And I don't just mean for the audience.

At some point in high school, dealing with a less-than-stellar 4 years, I learned that humor could be a coping mechanism for dealing with life's challenges. To some, it looked like being wacky or weird or just plain thinking too much. This disposition helped though. It didn't make pain magically disappear, but it did provide a path toward recovery that hadn't been within my grasp otherwise. It's a coping mechanism that sustains me through today.

This idea of a path toward resiliency is an important concept that I think often gets overlooked. It could be overwhelming (for me at least) to read or hear stories of people who overcame incredible hurdles through resiliency alone. I don’t know how to simply “will” myself to do anything, especially to find a way to toughen up and “just get through it”. Like anything of real value, it takes a path. For certain people, it is a strong religious or spiritual practice. For others, it may be a creative or physical commitment to keep moving forward. In my case, it is through a healthy sense of humor.

Humor is touchy, though, even for me. I had been putting off writing this blog because when one uses humor, there is always a risk (especially in today's day and age) that someone will be offended or misinterpret something. Many times, people confuse the use of humor to work through an issue with using it to simply diminish or dismiss. It's a fine line, often prone to different interpretations based on one’s upbringing, experiences, and overall demeanor.

That’s no reason to not rely on humor and its superpower, though. Recently, in an interaction with a friend over a few hours of talking and laughing about everything from white privilege to extreme "wokeness", she turned to me and said, "Thank you for the laughs, you have no idea how much I needed that."

That's what humor does. It helps get you through stuff and there's plenty of stuff to get through. Isn't that what resiliency is all about? Many times, it's little things. Sometimes, however, it's overwhelming challenges and it will take a lot more to find the humor but it's there. (Divorce, anyone?) Therein lies the recovery and the toughness part of resiliency. It might not be quick, but does that really mean you are any less resilient? It just may be time for a chat with both Merriam and Webster to see if we just can't tweak that definition a bit.

Here's the obvious truth; by the time you reach a certain age, you've probably been through some challenges. (Points to me, by the way, for using the word “challenges” instead of my word of choice which starts with “sh” and rhymes with “fit”.) By all accounts, I am an incredibly fortunate guy with two fantastic kids, my health (at least physical), a job that sustains us and a family and few close friends that love me. The rest is gravy. In the process of getting here, though, there's been bullying, divorce, break-ups, poor haircut choices, lapses in judgement, plenty of embarrassments, job loss and death.

Sure, these can dissolve the fabric of one's identity rather than help it to evolve. This is where resilience is most exciting; the growth that is the result of that stubborn fortitude. Have you seen any of my work performance reviews over the past couple of decades? I dare you to find one that doesn't have the word "persistent", "steadfast", "determined" or "stubborn" in it. I may not be on the radar for the next promotion but if we're ever in a hostage situation, I just may be your guy.

Don't get me wrong. I'm not some sort of Black Belt of resiliency. Occasionally, you might find me in the back yard, engaged in a cathartic primal scream. Eventually, though, I find the humor. Once I can find the funny, I start to gain perspective, which for me, is a key tenant of being resilient.

In case you’re wondering, don’t fret, you don't need to be funny to be resilient. So, go ahead – find your path. However, if you’re thinking of a career in stand-up comedy, resiliency is a must. If you've never questioned your life choices before, try an open mic night one of these days. It's humbling.

I've had an audience member call me an asshole during my set for reasons I have yet to uncover. And it turned out he was the next comedian to take the stage! I've been told I was more of a "fundraiser comic" than a "club comic" whatever that means. I've had negative comments about my jokes, my jeans and even my face. I've been brought to the stage where the host unenthusiastically pronounced, "Our next comic coming to the stage is Marc Kaye. Let's hope he's funny. If not, don't worry, we have a bunch of other comics after him." And these were some of my more successful gigs!

The point is, if you can't laugh about it, it makes the whole thing so much more difficult. There are things, for sure, that are just too painful to cope with using humor, at least for a while. This is where it is imperative to dig into our resiliency toolbox and see what else we have in there, meditation, exercise, prayer, or a pen and paper.

But, if it is applicable and you can find your funny bone somewhere cramped in a corner of that toolbox, dust it off and try it on. It might not speed up the path to developing a thicker skin or recovery, but it sure will make it just a bit more fun.

Thank you to Lise for the opportunity to contribute to her blog. I am grateful to find inspiration from her journey, writing and outreach.

About the author: Marc Kaye is the author of several articles and blogs featured in Working Mother, Stage Time Magazine, Chutzpah Magazine, Bucks County Alive and Green Energy Times. A Content Strategy and Engagement Leader by day and comedian, actor, and songwriter by night, he has developed several screenplays, short plays, web series and featured skits. His series of essays is set for release in 2022.

Marc received his B.S. in Biology and Psychology from Binghamton University and his M.B.A from Temple University. He is the founder of Eliro, www.eliro.us, a company that leverages the discipline of marketing and creativity of humor to help companies with employee engagement, brainstorming and strategy. A long-time resident of the Philadelphia region, he loves music, Swedish fish and babbling brooks (but not babbling people). You can find him online at www.marckayetoday.com.

Lise Deguire's gold award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.

June 4, 2021

How the Last-Picked-in-Gym Won a Gold Medal

In elementary school, my life divided into two clear zones. There were areas in which I excelled, and areas in which I was pitiful.

Looking for a good all-around student? That was me. Depending on the competition, I placed either at the top of the class, or hovered respectfully nearby. I was fine in math and science. I excelled in reading and social studies. In high school, I got a bit “distracted” and I under-performed. Just the same, you would have always wanted me on your academic team.

Sadly, there were no academic teams. No one got to pick me to be on “their reading team,” because there were no reading teams. There were, however, gym teams.

Only people of a certain age remember picking teams in gym, so let me set the stage. Picture an elementary school class, 28 kids or so, standing on a grassy field. It is gym time, and the class will play softball. But who goes on which team? The gym teacher, a gruff muscular woman who seems to dislike me, picks her two (athletic) favorite kids to be team captains. Then, the horror begins.

“Jimmy!” declares the first team captain, and who can fault him? Jimmy runs fast and has a great eye. Jimmy dashes over and stands behind his new team captain, head cocked.

“Patty!” shouts the second team captain. Patty, our most athletic girl, nods and sprints over to her captain, ponytail bouncing, blonde head held high.

Back and forth, the team captains make their choices, assessing their classmates like horses, selecting the best pitcher, the best catcher, or sometimes, their best friend. “Chris!” “Jennifer!” “Judy!” “John!”

The group in which I stand shrinks as our classmates get picked. Those of us left squirm, gazing down at the dirt. Hearing one’s name is a moment of profound relief because no one wants to be last. But really, they don’t have to worry, not when Lise Deguire is there.

I was always last. At the end, the team captain would be forced to mutter my name, when there was no one left but me. In a voice of despondency, I would hear “Lise.” Sometimes the entire team groaned. They knew that I would never hit the ball, catch the ball, or run to the base in time. My inclusion on their team sealed their inevitable loss. I would trudge toward my team, eyes downcast, apologetic for my very existence.

I have never won an award. OK, that isn’t true. I won “Most Improved” in swimming at summer camp when I was 10 years old. It was the only recognition for sports I ever achieved. “Most Improved” was a dubious distinction because, to be clear, I was truly THAT BAD.

Also, I did win two trivia contests on a cruise to Bermuda. The categories were “Beatles trivia” and “Show music trivia,” and I shouted aloud when I saw the contests listed on the activities schedule. These categories were clearly designed just for me and I SCORED in every possible way. But an award? Nope.

Until…

One recent morning, I awoke, with my usual middle aged aches and pains, and followed my dog downstairs. I checked my email and saw a message from a stranger. I hadn’t drunk my coffee yet, so my brain moved at early morning half-speed.

“We are excited and honored to announce that the new 2020 Nautilus Award winners are now posted.” I clicked on the proffered link with no expectations; I scrolled down. And there it was…

Memoir & Personal Journey… Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience From a Burn Survivor… GOLD!

Look, maybe if I hadn’t been humiliated in gym class for years, I would be more chill about this situation. Perhaps if I had been like Jimmy or Patty, I would smile and say, “Oh another award. How nice!” and then graciously move on to other topics. Instead, I have honestly been inserting the words “Gold medal” and “award-winning” into every possible conversation. I am shameless. I could talk about this award ALL DAY and I would really like to.

My poor husband has been bearing the brunt of my boundless glee. Making dinner, he glances up at me as I enter the room.

“Here I am, the award-winning author. Did I mention I won a gold award?”

He sighs. “How long do you think this is going to go on?”

I look at him, slightly indignant. “Please remember that I never won an award in my life and that I was last picked for gym every time for years.”

“Were you? Every time?”

“Yes.”

Doug looks away, chopping a carrot, and we pause. “OK, never mind then.”

There are many aspects to this development, and a lot more that I might say. Please know that:

1) My book was rejected by 34 publishers before I wound up self-publishing. That was like gym class all over again, let me tell you. But this time, this last-picked-by-publishers was able to start her own self-publishing team. So there!

2) I still have the gold medal Royal Caribbean gave me for winning those two trivia contests.

3) My book is about overcoming terrible odds, including many rejections, and eventually building a beautiful life. It seems VERY META that writing the book also involved overcoming terrible odds and many rejections, and eventually becoming an award-winning book.

4) Flashback Girl also just won another award: the Next Generation Indie Book Award for Memoir (Personal struggle, health issues), Finalist.

I don’t feel the need to crow as loudly and declare “Here I am, a finalist” because it just doesn’t have the same ring. But, still, I thought you should know.

I am told that kids in gym class don’t pick teams now. I was told this by my daughters’ elementary school gym teacher. They had a Family Fun Gym Day, which I heroically attended, a testament to my parental devotion. I entered the gym, feeling queasy. There were basketballs and wiffle bats, hula hoops and jump ropes. Although the floor sparkled from waxing, the gym still had that old smell, rubbery with the essence of youthful sweat.

I hovered, not picking up a ball, or doing anything to draw attention to myself. The gym teacher stood nearby.

“Want to join a game?”

“No,” I blurted out, and self-disclosed in a torrent. “I hate gym. I have always hated gym. I was last-picked every time.”

The gym teacher looked at me, and we locked eyes. Gym teachers always seemed to hate me. To my surprise, though, his eyes were sympathetic. “We don’t do that anymore. We would never do that to the kids.”

“Really?”

“Really.”

So, folks, I guess I am one of the last last-picked people. Thank goodness that future nonathletic kids won’t have to wait for their name to be called. But, for my friends out there, please remember this story if I start going on about these new awards. I promise I’m not bragging; I’m just making up for lost time.

Anybody want to pick me for their team now? Please?

Lise Deguire

Author of Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience From a Burn Survivor

2020 Nautilus Book Award for Memoir, Gold

2021 Next Generation Indie Book Award for Memoir, Finalist

1963-on, Terrible At All Sports.

One further note: Join us on June 5, at Commonplace Reader (Yardley) for a celebratory book signing, from 2:00-3:00 PM. Click here for details: https://patch.com/pennsylvania/yardle...

Lise Deguire's gold award-winning memoir, Flashback Girl: Lessons on Resilience from a Burn Survivor, is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Newtown Book Shop and The Commonplace Reader.