Peter Smith's Blog, page 92

March 14, 2016

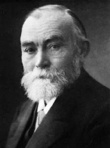

Hilary Putnam, 1926–2016

Such was Hilary Putnam’s very long winding path, his changes of direction, his jumpings across to traverse new fields, that different readers will surely be gripped by different stages of the journey.

For me, the really golden period was from about 1960 to 1975. It is difficult now to overestimate the impact of Mathematics, Matter and Method, and Mind, Language and Reality, the first two volumes of his Collected Papers, which CUP brought out in 1975. Of course, we knew some of those 41 papers, originally published in very widely scattered places, if published at all. But bringing them together revealed Putnam to be an extraordinarily fertile, imaginative philosopher, unpicking the legacies of verificationism and behaviourism in defence of sane realisms about science and the mind. It helped too that he wrote with such stylish clarity, carrying an enviable amount of background technical knowledge lightly. I thought at the time that those papers exemplify analytical philosophy at its best. And I’d still warmly recommend any student beginning the serious study of philosophy to read the Putnam of those years. Such a very fine philosopher.

March 11, 2016

One future for journal publishing, revisited

Back in September, I noted that Tim Gowers announced a new journal, Discrete Analysis. As I said then, the content of the journal probably won’t be of much interest to most readers of Logic Matters. But the form of the journal is fascinating. It is to be an arXiv overlay journal. In the briefest headline terms, what this means, in Tim Gowers’s words, is that

rather than publishing, or even electronically hosting, papers, it will consist of a list of links to arXiv preprints. Other than that, the journal will be entirely conventional: authors will submit links to arXiv preprints, and then the editors of the journal will find referees, using their quick opinions and more detailed reports in the usual way in order to decide which papers will be accepted. … [So] The articles will be peer-reviewed in the traditional way.

The first issue is now online. And rather striking it looks too. There is more about the launch issue and the project in Tim Gowers’s latest blogpost. I wonder if any logicians out there will be spurred on to think about starting such an open-access journal? It seems a terrific idea.

By the way, for those of you with some little maths, if you click on the banner for the lead article, you get a short editorial intro. to Terence Tao’s paper, and — this is nice touch! — a link to a video of a talk that Tao gave about his proof, which (even if you don’t really follow the later parts of it) gives you a sense of what’s going on.

March 10, 2016

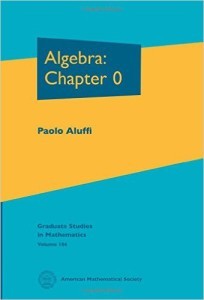

Book Note: A little light algebra

Suppose, e.g. as a philosopher of mathematics, you want to get to know more mathematics (after all, it is always a jolly good idea for a philosopher of X to know more than a mere smidgin about X). One area which you have seen to be absolutely central to the modern mathematical curriculum is abstract algebra. Fine: but what to read if — quite a big ‘if”! — you do decide to get to know more about this?

Suppose, e.g. as a philosopher of mathematics, you want to get to know more mathematics (after all, it is always a jolly good idea for a philosopher of X to know more than a mere smidgin about X). One area which you have seen to be absolutely central to the modern mathematical curriculum is abstract algebra. Fine: but what to read if — quite a big ‘if”! — you do decide to get to know more about this?

It depends what base you are starting from, of course. At a really introductory level (first year undergraduate, perhaps), one really nice option which I can warmly recommend is Alan Beardon’s relatively short Algebra and Geometry (CUP, 2005), which is very well put together and indeed not-too-abstract. But perhaps this doesn’t take you far enough to get a more rounded sense of modern algebra.

So suppose you want more than you’ll get from Beardon; or perhaps you already have some — possibly fragmentary, possibly half-remembered — knowledge of algebra, and want to go up a level in sophistication and detail. What then? One option is Saunders Mac Lane and Garrett Birkhoff’s Algebra (3rd edition, AMS Chelsea, 1999). This is a distant and slightly more advanced descendant of their famous A Survey of Modern Algebra (which originally dates back to 1941), and is notable for the way it weaves into the story categorial ideas, with a fairly light hand and in an illuminating way. But the treatment is quite brisk, and I think there is now a better option, taking quite a similar approach, but in a rather more engaging way. This is Paolo Aluffi’s Algebra: Chapter 0 (American Mathematical Society, 2009). Its presentation of even quite complex ideas is typically exemplary, both in giving motivation, and in explaining official definitions, presenting the proofs etc, and all often written with a light touch. So this is admirable. and I think is particularly suitable for self-study.

The chapter titles indicate the coverage. I, Preliminaries: sets and categories (so yes there is early introduction to categorial ideas, but again done with a light touch, emphasising the notion of ‘universal properties’). II, Groups, first encounter (the basics done very clearly). III, Rings and Modules (getting as far as a first look at complexes and homology and exact sequences). IV, Groups, second encounter. V, Irreducibility and factorization in integral domains. VI, Linear algebra. VII, Fields. VIII, Linear algebra, reprise. IX, Homological algebra. So things eventually get pretty serious, and you can bail out well before the end but still with a good sense of the topics and approach of modern algebra.

These days, alternative standard recommendations for tackling algebra at this sort of level include e.g. Serge Lang’s Algebra (3rd revised edition, Springer, 2002), and David Dummit and Richard Foote’s Abstract Algebra (3rd edition, Wiley, 2004). But these are quite a bit longer than even Aluffi’s weighty volume, and really cover unnecessarily much (for our purposes). And, more to the current point, I would say neither is a particularly attractive read.

So headline summary: if you want to learn some algebra, dive into Aluffi’s Algebra: Chapter 0.

March 9, 2016

And now we are ten …

Francesco Guardi: Forte S. Andrea Del Lido, Venice.

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

This blog started ten years ago today. We’ve survived. So let’s have a birthday card, a favourite picture, from down the road in the Fitzwilliam.

March 7, 2016

Encore #20: Keeping on keeping on …

I am getting ever-more buried in the expositional details of re-writing/expanding my Gentle Introduction to category theory. Which is fun, if you like that kind of thing, and I’m learning a great deal from the exercise: but it is not really the sort of project liable to prompt snappy blog contributions. Techie details won’t be of interest to many; and more philosophical ruminations are difficult to keep focused. So I suspect that contentful logical posts may become (even more) sporadic. You’ll just have to make do with the non-logical bloggings! — like this last pre-birthday encore. This is a repost from only a few months ago, and the thoughts are still very much in my mind.

Until the lights go out (Aug 18, 2015)

“If you don’t know the exact moment when the lights will go out, you might as well read until they do.” I think I will adopt that as my motto. It’s from Clive James, in the Introduction to his Latest Readings which comes out next week, a little book that reflects on a delightfully idiosyncratic range of authors and books. James is still reading, and writing too with humanity and wit and insight and, as we say, with undying enthusiasm. Except our author is dying. Though he confesses to feel “the childish urge to understand everything”, an urge which “doesn’t necessarily fade when the time approaches for you to do the most adult thing of all: vanish”.

I’ve been living the last few weeks with Clive James’s previous book, Sentenced to Life. We share the same still-small town-within-a-city, share similarly eclectic tastes (or perhaps not so much eclectic as tastes that place us in the same generation and in somewhat overlapping worlds), and share some favourite authors: we also share rather more that I wish we didn’t. So I have been finding these last poems (if that’s what they prove to be) speaking particularly directly. Poignant, regretful, looking death in the face without illusion. And very accessible too – as if, by imposing such clear form, such unabashed rhyming structures, our poet is making his stand against the formlessness to come. There is no false consolation here. But still (as Blake Morrison puts it in a review) “When in death, we’re in the midst of life – that’s the recurrent, bleakly hopeful theme.”

Not that it is all bleak. Far from it. There is still Jamesian fun to be had: his Compendium Catullianum, for example –

My girlfriend’s sparrow is dead. It is an ex-sparrow.

Though after the jests, we are back to a recurrent thread: “For I …

Miss you the way you miss that stupid bird:

Excruciating. Let’s live and let’s love.

Our brief light spent, night is an endless sleep.

And our poet, before the lights go out, is so vividly aware of the small particulars of his ever-narrowing world:

Once I would not have noticed; nor have known

The name for Japanese anemones,

So pale, so frail. But now I catch the tone

Of leaves. No birds can touch down in the trees

Without my seeing them. I count the bees.”

I can recognise that. And so much else here.

I would quote whole poems from Sentenced to Life if I could. But here is one of the last poems, one of my favourites, first published a year ago in the New Yorker.

March 6, 2016

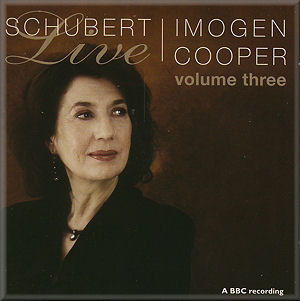

Encore #19: Schubert’s piano music

Is it something about the philosophical temperament? But I have known a number of philosophers for whom Schubert’s later piano works are absolutely central among the music which means the most to them. Certainly they are for me. I have blogged over the years about a number of recordings — more than I realised — including these posts:

From 2009 Sometimes, in an idle moment, I jot down — be honest, don’t we all? — a list of the eight discs I would select as my Desert Island Discs. Impossibly difficult of course! But one constant choice is the last Schubert piano sonata, D960 (and if I had to save one of the eight discs from the waves, then this would probably be it). But which recording? Well, that’s almost impossible too. … I still think that that has to be one of the Brendel recordings: after listening to others, I always listen to him again with a sense of coming home. Perhaps I love his 1988 recording the most.

From 2010 The third double-CD has recently been released of Imogen Cooper’s stunning journey through late Schubert in her QE Hall recitals in 2008 and 2009. The first two pairs of disks got some extraordinarily warm reviews, and this too strikes me as just wonderful. Thoughtful, deep, utterly persuasive. And lyrically beautiful.

From 2010 The third double-CD has recently been released of Imogen Cooper’s stunning journey through late Schubert in her QE Hall recitals in 2008 and 2009. The first two pairs of disks got some extraordinarily warm reviews, and this too strikes me as just wonderful. Thoughtful, deep, utterly persuasive. And lyrically beautiful.

At the end of the second of the new disks she reaches the pinnacle, the end of her journey — an amazing performance of D. 960. As I said in an earlier post, I’ve accumulated over too many years recordings of this sonata played by Schnabel, Richter twice, Brendel three times, Schiff, Kovacevich, Perahaia, Uchida, and Lewis as well as the earlier Imogen Cooper; and yet here are new insights, a wonderful overall architecture, and an utterly compelling performance. This could well become my new “Desert Island” choice of all those performances.

From 2011 Here’s some other recordings to recommend — the new two CD set of Schubert from Paul Lewis, the D. 850 Sonata, the great D. 894 G major, the unfinished ‘Reliquie’ D. 840, the D.899 Impromptus — and last but very certainly not least the D. 946 Klavierstücke (try the second of those last pieces for something magical again). By my lights, simply wonderful. I’ve a lot of recordings of this repertoire, but these performances are revelatory. Which is a rather feebly inarticulate response, I do realize — sorry! But if you love Schubert’s piano music then I promise that this is just unmissable.

From 2011 Thanks to Askonas Holt, her agents, three videos of Imogen Cooper playing at a concert in 2009 have just been posted on YouTube (the video isn’t HD, but the sound is just fine). There is a nice performance of Schubert’s Hungarian Melody D817, and a lovely short piece of Janacek, ‘Good Night’ from On an Overgrown Path, which I haven’t heard for ages. But then, on a quite different scale of length and emotional intensity, she is joined by Paul Lewis for a stunning performance of the Schubert Fantasie D940. And this is surely as good as it gets: two of the greatest Schubert pianists seemingly as one in their shared vision of the piece. Just wonderful.

From 2013  Suppose, just suppose, that one of the very greatest and most loved actors of his (or her) generation was tackling one of the high peaks of the repertoire, returning perhaps to a previous near-triumph with a quarter of a century’s more experience. Every broadsheet would have extensive reviews, though telling most readers about a performance they will never see (even if in reach of London and in funds to make the journey), because the tickets have long since sold out. There will be interviews with the actor, even colour-supplement spreads. You know how it goes.

Suppose, just suppose, that one of the very greatest and most loved actors of his (or her) generation was tackling one of the high peaks of the repertoire, returning perhaps to a previous near-triumph with a quarter of a century’s more experience. Every broadsheet would have extensive reviews, though telling most readers about a performance they will never see (even if in reach of London and in funds to make the journey), because the tickets have long since sold out. There will be interviews with the actor, even colour-supplement spreads. You know how it goes.

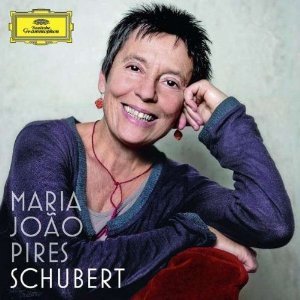

Now here is one of the very greatest and most admired pianists of her generation, still at the very height of her powers, returning to Schubert’s last piano sonata, a quarter of a century after a very fine earlier recording. You would have thought that the broadsheets with arts pages would at least notice this major event. After all, nearly all their readers can afford the CD, which is so accessible that it will arrive at the click of a button. So here surely is something worth reviewing. Here too perhaps is even an occasion for a retrospective pieces on a remarkable artist. But no. As far as I’ve seen, nothing. Which is not at all unusual these days. It is difficult not to feel (as you do when look round your fellow concert-goers, noting all the grey heads) that slowly but inexorably a deep engagement with classical music is becoming less and less central to our cultural life.

Well here, let it be said, is the most extraordinary music-making, indeed inviting the most personal engagement. Maria João Pires offers us a performance of the A Minor Sonata D845 played with intense intimacy. There is nothing declamatory here: she is sitting across the room, playing for us listening, close around her. There’s a care to every phrase which isn’t mannered, wonderful lightness of touch when called for, and moments when time is slowed to a pause (her magical way with the Trio of the third movement). For this sonata alone you will want the disc.

But then there is D960. What is to be said? For many, this is very high on the list of the music that matters the most, that has to be returned to time and again. We have a most wonderful inheritance of recordings from Schnabel onwards of this “music which … is better than it can be performed”. Brendel, Richter and Imogen Cooper, all more than once, Lupu, Kovecevich and Uchida — all are stunning in their different ways, all their recordings are to be listened to repeatedly. And Pires herself recorded the sonata 25 years ago.

It would be absurd (or at least absurd for me) to try to make comparisons. Let me just say that this new recording is surely a more than a worthy addition to that great inheritance. This is not one of those more brooding performances where we are made conscious from the beginning that this is the work of a dying man (performances which give the first movement such ominous weight as to unbalance the whole sonata). There is an intimate directness to her undeclamatory opening: again, we are sitting with Pires — she is not addressing us across a concert hall. And it is only slowly that the intensity is ratcheted up in the first movement (especially about 11 minutes in), and then we are gripped by a new tension as the opening theme and development return once more. The following Andante sostenuto is unsentimental, played with a rhythmic delicacy that becomes magical. The Scherzo is played vivace con delicatezza as Schubert asks: but Pires deconstructs the Trio with bass emphases which I can’t recall being made quite so aware of before, harking back to previous movements. The final Allegro has moments of lightness again but also a certain weight and drive giving a more-than-satisfying balance to the whole sonata, the tumbling final chords finishing in a sudden silence.

This won’t replace your other recordings of D960, how could it? But you will want to listen and listen again, and you will hear more from Pires each time. Wonderful.

From 2015 I buy too many CDs and we go to a fair number of concerts, and so I usually blog only about some of the ‘five star’ discs or concerts which bowl me over. Which does mean that when I do offer reviews, they tend to be consistently full of superlatives. It is certainly not that I’m an uncritical listener: very far from it. Still, I don’t want to be carping or tediously negative here (I’ll keep that for the philosophy!). I prefer to write about music, when I do, from heartfelt enthusiasm. And this time, the enthusiasm is for David Fray’s latest CD.

One of the very finest Schubert recordings of the last ten years, it is widely agreed, is Fray’s CD of the Op 92 Impromptus and the Moments Musicaux. He plays those pieces with luminous artistry and acute sensitivity — taking some notably slow tempi yet never seeming mannered or other than fully immersed in the complexities and ambiguities of Schubert’s music. There is, I have remarked elsewhere, something Richter-like in Fray’s intensity, and in his wonderful ability to impose his vision of the music.

One of the very finest Schubert recordings of the last ten years, it is widely agreed, is Fray’s CD of the Op 92 Impromptus and the Moments Musicaux. He plays those pieces with luminous artistry and acute sensitivity — taking some notably slow tempi yet never seeming mannered or other than fully immersed in the complexities and ambiguities of Schubert’s music. There is, I have remarked elsewhere, something Richter-like in Fray’s intensity, and in his wonderful ability to impose his vision of the music.

Fray has now returned to Schubert, and indeed firstly to a piece indelibly associated with a quite extraordinary recording by Richter — the G major sonata D894. And the comparison in some ways is still very apt. For Fray too takes the first movement unusually slowly. Where, for example, Brendel in his later digital recording takes 17′.16″ and Paul Lewis 17′.28″ — both very fine performances — Fray takes 19′.06″. This still falls far short of Richter’s astonishing, bordering-on-the-perverse, 26′.51″ in the (in)famous 1979 recording. Yet here is the magical thing: from Fray’s way with his very slight holdings-back, the slightest hesitations, to his control of the architecture of the movement, everything gives his performance a seeming scale closer to Richter’s. (He takes little more than half a minute more than Mitsuko Uchida’s 18′.29″ and yet Fray’s first movement at crucial moments seems markedly more spacious.)

Another magical thing is the wonderfully nuanced clarity of Fray’s playing here — effortlessly cantabile passage work, forte passages which never become brashly declamatory, unending attention to detail with nothing exaggerated or out of place.

Now, there can be a problem — can’t there? — with performances of some of Schubert’s major works: how to make a satisfying whole of a piece that starts with one or two immense movements — immense both in scale and emotional weight. (One of the many things that I particularly admire about the Pavel Haas Quartet’s Schubert CD which I reviewed here is the extraordinarily balance they achieve across the four movements of Death and the Maiden and again of the String Quintet.) How does the rest of David Fray’s performance of the ‘Fantasie’ sonata hold up against this test?

Extraordinarily well, I would say. Partly this is because, although the first movement is played very expansively, it is never becomes heavy. And partly because of the compelling readings he gives of the other movements. I was rather surprised, when I checked, that Fray’s timings in the last three movements are all rather quicker than Brendel, Lewis and Uchida. Yet he plays with such grace and attention to texture and detail that Schubert’s music is given all the space it needs, and there are again quite magical touches. The Trio in the third movement catches with your breath. The final Allegretto dances through its episodes with a wonderful lightness of touch in building to its conclusion.

In short, I would say that of the dozen or more great performances of the G major sonata that I have on disc, this is at least as fine as any: it is worth getting Fray’s new CD for this alone.

But there is much more. Fray follows with a lovely performance of the haunting Hungarian Melody D817. And then for the last two major pieces on the CD he is joined by his one-time teacher Jacques Rouvier. First, they play the Fantasia in F minor D940. This, the incurable romantics among us will remember, was dedicated by Schubert to his young pupil the Countess Karoline Esterházy, often thought to have been the object of his hopeless love: and the piece certainly calls for yearning and passion. I have long loved the old recording from 1978 by Imogen Cooper and Anne Queffélec. But Fray and Rouvier are perhaps even better. Certainly, the yearning in the first dotted theme (with its Hungarian echoes) is as intense; the passion as the music then goes through its evolving moods — stormy, a burst of sunshine, clouds regathering interspersed with more moments of fleeting happiness — is as heartful; the moment when the first yearning theme returns is as affecting; the build-up through the fugato passage to the very final appearance of the initial theme as the music comes to its abrupt recognition that the yearning is indeed hopeless, all this is wonderfully well done.

The CD concludes with the ‘Lebensstürme’ Allegro D947. This is not, for whatever reason, my favourite Schubert piano music: but again surely it could not be played better than it is here. A wonderful disc then, most warmly recommended. (And there is, by the way, a video about this CD on David Fray’s website.)

March 5, 2016

Encore #18: With a little help from my friends

The internet, we all know, some to very considerable cost, is a mixed blessing. But my experience with Logic Matters at least has been all positive. In particular, in 2012 when I was getting near to finalising the second edition of my Gödel book, it led to a very cheering episode. In late July that year, I posted:

In the immortal words of Douglas Adams, “I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by.” The second edition of my Gödel book was supposed to be off to CUP today for the proof-reading stage. But it will be two or three weeks yet. Still, the end is in sight …

I’ll be sending out the complete draft PDF to a few very kind people who have given me comments on the early chapters that I’ve posted here. But would you like to see the whole draft PDF when it is done in a couple of weeks (and maybe see your name in illuminated letters on the Acknowledgements page for the book)? Then here’s the deal …

Send me an email with the subject line “Proof reading Gödel” … from an academic email address, with a sentence or two about you, promising

not to pass on the PDF,

to do a very careful proof-reading for typos, cross-checking of references etc., of an assigned chunk of the book [about 30 pages] as quickly as you can, and definitely within three weeks of getting the PDF,

to comment on any issues of readability etc. in that chunk.

Of course, comments on more would always be most welcome, even at this late stage! Since I’ll be producing the camera-ready copy for the book, I can make changes up to the wire (which will no doubt be at least a couple of months after I first send in the draft to CUP for their proof reader and production team to take a first look at).

Oh, how can you resist the offer!?

I also posted the same offer on the FOM list. The response to the two postings, as I reported a few days later, was terrific:

I’ve had a wonderful response to the invitation here to proof-read/comment on chunks of Gödel Mark II, enough to ensure that every chapter will be covered at least a couple of times. There was a (very) small bribe attached: but quite a few made friendly offers saying that they’d like to join in as they had enjoyed the first edition. Which is very nice to know! Corrections and suggestions from these new recruits assigned early chapters to review are already beginning to arrive, to add to those from some previous much-valued correspondents, as I finishing tinkering with the last chapters. Just terrific. It’s going to be a very busy few weeks ahead, but the book will end up a lot better for it.

The possibility of this kind of supportive exchange via the internet, and the availability of wonderful resources like mathoverflow.net of math.stackexchange.com, make trying to write a logic book in 2012 so very much more enjoyable (and a much less stressful experience) than even ten years ago. Many thanks to all my virtual logical colleagues out there!

And a couple of weeks later:

This last phase of writing has been a lot more enjoyable and less stressful than it might have been because of the input and warm encouragement I have had from over forty kind people in response to my invitation here and elsewhere to help proof-read chunks of the book. With most of the responses in, that has worked quite wonderfully well. Most chapters have now been looked at by three readers, with different readers bringing a different mix to the party. Some are particularly eagle-eyed at spotting typos, some very helpful about picking up sentences that don’t read well to non-native English speakers, some are good at finding nice ways of rephrasing to avoid possible misunderstanding, some have helpful suggestions about when yet-another-reference or yet-another-footnote would in fact be a good idea, some are stern about ‘that’ vs ‘which’, some have an enviably secure grasp of the True Difference Between a Colon and a Semi-colon, and so it goes. And everyone has evidently put a lot of care into their close-reading.

The proof-readers have been a very mixed bunch, lots of grad students of course, but also senior undergraduates, established professors, and a sprinkling of ‘amateurs’ who have done some logic in the past and are now out of academia. And (perhaps rather useful info for anyone thinking of emulating this exercise in crowd-sourcing the fine-tuning of a logic text), there seems to have been zero correlation between official status and the giving of particularly valuable comments.

I’m really grateful to everyone. All shall have prizes. Or at least, have their name in lights in the book.

And indeed they did have their names in lights. The result wasn’t perfect — see the corrections list! However, as you’ll also see from the list, the residual errors were almost all tiny and not likely to put a reader off their stride. So the experiment certainly worked. But, as I say, more than that, it was a rather cheering experience of friendly helpfulness from a lot of people.

March 2, 2016

Encore #17: Larkin was right …

The old always think the world is going to the dogs. I try to resist. Sometimes, though, it is difficult.

Going, gone (Nov 23, 2011)

The main road west from Cambridge used to go down the main street of the market town of St. Neots before crossing the river. But there has long since been a bypass, and it is quite a while since I’ve chosen to turn off it to take the old route. But I wanted a coffee, so today I stopped in the town and went to a scruffy and run-down branch of Caffè Nero on the large market square.

Their espresso wasn’t very good, but that’s probably only to be expected. What I hadn’t really bargained for was just how depressing the view out to the square is now. Even on a bright autumn morning, it looked as scruffy and run down as the coffee shop. This was never a very wealthy place: but there was once some small domestic grace to the surrounding mostly nineteenth century buildings. But now many of them are quite disfigured with the gross shop-fronts of cheap stores, and others look miserably unkempt. There’s a particularly vile effort by the HBSC bank, which gives a special meaning to “private affluence and public squalor” — only an institution with utter contempt for its customers and their community could plonk such a frontage onto a main street. Where once even small-town branches of banks were solid imposing edifices in miniature, with hints of the classical orders here and a vaulted ceiling there, signifying permanence and reliability, now they are seem to take pride in having all the visual class of a here-today, gone-tomorrow betting shop. How appropriate.

And the square itself (like so many other urban spaces in England) seems to have been repaved on the cheap, with the kind of gimcrack blockwork that always seems, a few years in, to settle into random waves of undulation. The bleakly open space cries out for more trees to surround it, and inviting wooden seats. But no, on non-market days it is just the inevitable carpark.

Next to coffee shop, still on the square, a horrible looking cafe is plastered outside with pictures of greasy food. I walk a little further down the road before driving on. It is a visual mess. Even Marks and Spencer manages a particularly inappropriate shout of a shop-front, as sad-looking charity shops cringe nearby. Could anyone feel proud or even fond of this street as it now is?

A couple of hundred yards away there are lovely water-meadows by the bridge over the river, and some fancy residential developments. On the outskirts of town the other side, as the road leaves towards Cambridge, there is a lot more quite expensive-looking new housing (though heaven knows how it will seem a few years hence). But the town centre itself is in such a sorry state.

“Most things are never meant,” wrote Larkin when he foresaw something of this in ‘Going, going’. And we — I mean my generation, for it is we who were in charge — surely didn’t mean this, for the hearts of old country towns like St. Neots (or the larger next town, Bedford) to become such shabby, ugly, run-down places. But it has happened apace, all over the country, and on our watch.

Philip Larkin reads ‘Going, going’.

March 1, 2016

Analysis

I am delighted to hear from Chris Daly that David Liggins and he (both at Manchester) are to become joint editors of Analysis (which once upon a long time ago, I edited for a dozen years). I can’t imagine the journal being in better hands, and am very sure it will really flourish in their hands.

Encore #16: Weir’s formalism

One of the books which I blogged about at length here was Alan Weir’s Truth Through Proof (OUP, 2010). I found this difficult and puzzling, but also enjoyable to battle with (not least because Alan responded in comments at length). Things soon got intricate, but here is a (revised version) of a very early post in the series, where I try to initially locate Alan’s position on the map. So this is perhaps of stand-alone interest, and there are themes here connecting to issues raised in the previous Encore on Maddy.

TTP, 2. Introduction: Options and Weir’s way forward (May 30, 2011)

Our conception of ourselves as natural agents without God-like powers “imposes a non-trivial test of internal stability” (as Weir puts it) when combined with platonism. As Benacerraf frames the problem in his classic paper, ‘a satisfactory account of mathematical truth … must fit into an over-all account of knowledge in a way that makes it intelligible how we have the mathematical knowledge that we have’. Faced with this challenge, what are the options? Weir mentions a few; but he doesn’t give anything like a systematic map of the various possible ways forward. It might be helpful if I do something to fill the gap — not a complete map, of course, but noting various choice points, and the way Weir goes at each.

Start with this question:

Can we say — without qualification, without our fingers crossed behind our backs! — that yes, 3 is prime and, yes, the Klein four-group is the smallest non-cyclic group?

The platonism will answer ‘yes’. A gung-ho fictionalist of a certain stripe, for instance, will say ‘no’, our ordinary talk of numbers or groups commits us to a platonist ontology of abstracta that a sensible naturalist with a coherent epistemology has no business believing in: the mathematical claims, as they stand, unqualified, are false.

Platonists, however, aren’t the only people who answer ‘yes’ to 1. Move on, then, to a second question:

Are ‘3 is prime’ and ‘the Klein four-group is the smallest non-cyclic group’, for example, to be construed — as far as their ‘logical grammar’ is concerned — at face value, as the surface form suggests (on the same plan as e.g. ‘Alan is clever’ and ‘the tallest student is the smartest philosopher’)?

A more conciliatory stripe of fictionalist can answer ‘yes’ to (1) but ‘no’ to (2), since she doesn’t take ‘3 is prime’ as wearing its logical form on its face but re-construes it as short for ‘in the arithmetic fiction, 3 is prime’ or some such. Likewise, for a certain brand of naive (or naive-ish) formalist who takes ‘3 is prime’ as not attributing a property to a number but as saying that a certain sentence can be derived in a formal game.

Eliminative and modal structuralists will also answer ‘yes’ to (1) and ‘no’ to (2), this time construing the mathematical claims as quantified conditional claims about non-mathematical things (schematically: anything, or anything in any possible world, that satisfies certain structural conditions will satisfy some other conditions). It is actually none too clear how structuralism helps us epistemologically, and when given a modal twist it’s not clear either how it helps us ontologically. But that’s quite another story.

Suppose, however, we answer ‘yes’ to (1) and (2). Then we are committed to agreeing that there are prime numbers and there are non-cyclic groups, etc. (for it is true that 3 is prime and that the the Klein four-group is the smallest non-cyclic group, and — construed as surface form suggests — that requires there to be prime numbers and non-cyclic groups). Next question:

Is there a distinction to be drawn between saying there are prime numbers (as an unqualified truth of mathematics, construed at face value) and saying THERE ARE prime numbers? – where ‘THERE ARE’ indicates a metaphysically committing existence-claim, one which aims to represent how things stand with ‘denizens of the mind-independent, discourse-independent world’ (following Weir in borrowing Terence Horgan’s words and Putnam’s typographical device)

According to one central tradition, there is no such distinction to be drawn: thus Quine on the univocality of ‘exists’.

The Wright/Hale brand of neo-Fregean logicism likewise rejects the alleged distinction. Their opponents are sometimes puzzled by the Wright/Hale argument for platonism on the cheap. For the idea is that, once we answer (1) and (2) positively (and just a little more), i.e. once we agree that ‘3 is prime’ is true in some anodyne, minimalist, sense, and that ‘3’ walks, swims and quacks like a singular term, then we are committed to ‘3’ being a successfully referring expression, and so committed to its referent, which (on modest and plausible further assumptions) has to be an abstract object; so there indeed exists a first odd prime which is an abstract object. Opponents think this is too quick as an argument for full-blooded platonism because they think there is a gap to negotiate between the likes of ‘there exists a first odd prime number’ as an anodyne mathematical truth and ‘THERE EXISTS a first odd prime number’. Drawing on inter alia early Dummettian themes (which have Fregean and Wittgensteinian roots), the neo-logicist platonist denies there is a gap to be bridged.

Much recent metaphysics, however, sides with Wright and Hale’s opponents (wrong-headedly maybe, but that’s where the troops are marching). Thus Ted Sider can write ‘There is a growing consensus that taking ontology seriously requires making some sort of distinction between ordinary and ontological understandings of existential claims’ (that’s from his paper ‘Against Parthood’). From this perspective, the claim would be that we must indeed distinguish granting the unqualified truth of mathematics, construed at face value, from being committed to a full-blooded PLATONISM which makes genuinely ontological claims. It is one thing to claim that prime numbers exists, speaking with the mathematicians, and another thing to claim that THEY EXIST ‘in the fundamental sense’ (as Sider likes to say) when speaking with the ontologists.

Now, we can think of Sider et al. as mounting an attack from the right wing on the Quine/neo-Fregean rejection of a special kind of philosophical discourse about what exists: the troops are mustered under the banner ‘bring back old-style metaphysics!’ (Sider: ‘I think that fundamental ontology is what ontologists have been after all along’). But there is a line of attack from the left wing too. Consider, for example, Simon Blackburn’s quasi-realism about morals, modalities, laws and chances. Blackburn is no friend of heavy-duty metaphysics. But the thought is that certain kinds of discourse aren’t representational but serve quite different purposes, e.g. to project our moral attitudes or subjective degrees on belief onto the world (and a story is then told about why a discourse apt for doing that should to a large extent retain the same logical shape of representational discourse). So, speaking inside our moral discourse, there indeed are virtues (courage is one): but as far as the make-up of the world on which we are projecting our attitudes goes, virtues do not EXIST out there. From the left, then, it might be suggested that perhaps mathematics is like morals, at least in this respect: talking inside mathematical discourse, we can truly say e.g. that there are infinitely many primes; but mathematical discourse is not representational, and as far as the make-up of the world goes – and here we are switching to representational discourse – THERE ARE NO prime numbers.

To put it crudely, then, we can discern two routes to distinguishing ‘there are prime numbers’ as a mathematical claim and ‘THERE ARE prime numbers’ as a claim about what there really is. From the right, we drive a wedge by treating ‘THERE ARE’ as special, to be glossed ‘there are in the fundamental, ontological, sense’ (whatever that exactly is). From the left, we drive a wedge by treating mathematical discourse as special, as not in the ordinary business of making claims purporting to represent what there is.

And now we’ve joined up with Weir’s discussion. He answers ‘yes’ to all three of our questions. A fourth then remains outstanding:

Given there is a distinction between saying that there are prime numbers and saying THERE ARE prime numbers, is the latter stronger claim also true?

If you say ‘yes’ to that, then you are buying into a version of platonism that does indeed look epistemically particularly troubling (in a worse shape, at any rate, than for the gap-denying neo-logicist position; for what can get us over the claimed gap between the ordinary mathematical claim and the ontologically committing claim)? Weir thinks this position is hopeless. Hence he answers ‘no’ to (4). Hence he endorses claims like this: There are infinitely many primes but THERE ARE no prime numbers. (p. 8 )

But this isn’t because he is, as it were, coming from the right, deploying a special ‘ontological understanding of existence claims’. Rather, he is coming more from the Blackburnian left: his ‘THERE ARE’ is ordinary existence talk in ordinary representational discourse, and the claim is that ‘there are infinitely many primes’, as a mathematical claim, belongs to a different kind of discourse.

OK, what kind of discourse is that? “The mode of assertion of such judgements, I will say, is formal, not representational”. And what does ‘formal’ mean here? Well, part of the story is hinted at by the claim that the formal, inside-mathematics, assertion that there are infinitely many primes is made true by “the existence of proofs of strings which express the infinitude of the primes” (p. 7). Of course, that raises at least as many questions as it answers. There are hints in the rest of the Introduction about how this initially somewhat startling claim is to be rounded out and defended in the rest of the book. But they are much too quick to be usefully commented on here; so I think it will be better to say no more here but take them up as the full story unfolds.

Still, we now have an initial specification of Weir’s location in the space of possible positions. His line is going to be that, as a mathematical claim, it is true that are an infinite number of primes: and this truth isn’t to be secured by reconstruing the claim in some fictionalist, structuralist or other way. But a mathematical claim is one thing, and a representational claim about how things are in the world is another thing. And the gap is to be opened up, not by inflating talk of what EXISTS into a special kind of ontological talk, but by seeing mathematical discourse (like moral discourse) as playing a non-representational role (or dare I say: as making moves in a different language game?). That much indeed sounds not unattractive. The question is going to be whether the nature of this non-representational game can be illuminatingly glossed in formalist terms. Now read on …

If you want to follow the discussions of Alan Weir’s book here on the blog, with some illuminating replies by Alan, then here they are (in reverse order). The long review I wrote for Mind is here.